Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and I.S.S.; methodology, I.S.S. and N.B.; software, I.S.S.; validation, N.B. and G.-V.I.; formal analysis, I.S.S., N.B., and G.-V.I.; investigation I.S.S., N.B., and G.-V.I.; resources, N.B. and G.-V.I.; data curation, N.B. and G.-V.I.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.S.; writing—review and editing, N.B. and G.-V.I.; visualization, N.B.; supervision, N.B. and G.-V.I.; project administration, N.B.; funding acquisition, N.B. and G.-V.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

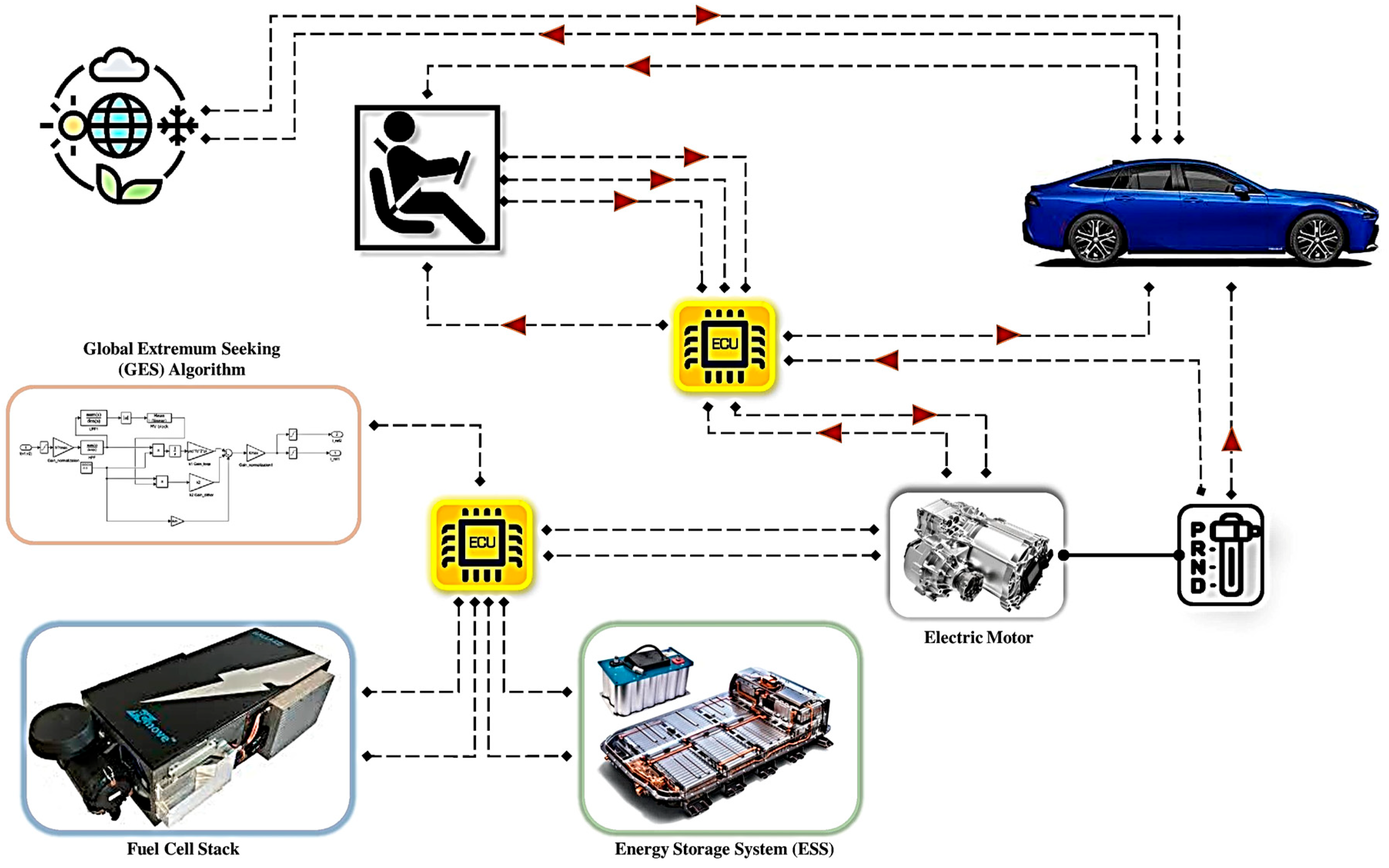

Figure 1.

Fuel cell hybrid power system architecture.

Figure 1.

Fuel cell hybrid power system architecture.

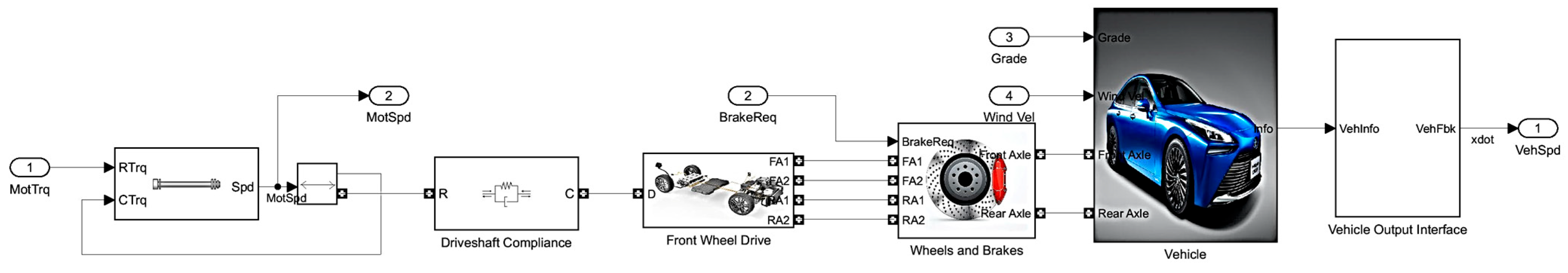

Figure 2.

Fuel cell hybrid powertrain architecture.

Figure 2.

Fuel cell hybrid powertrain architecture.

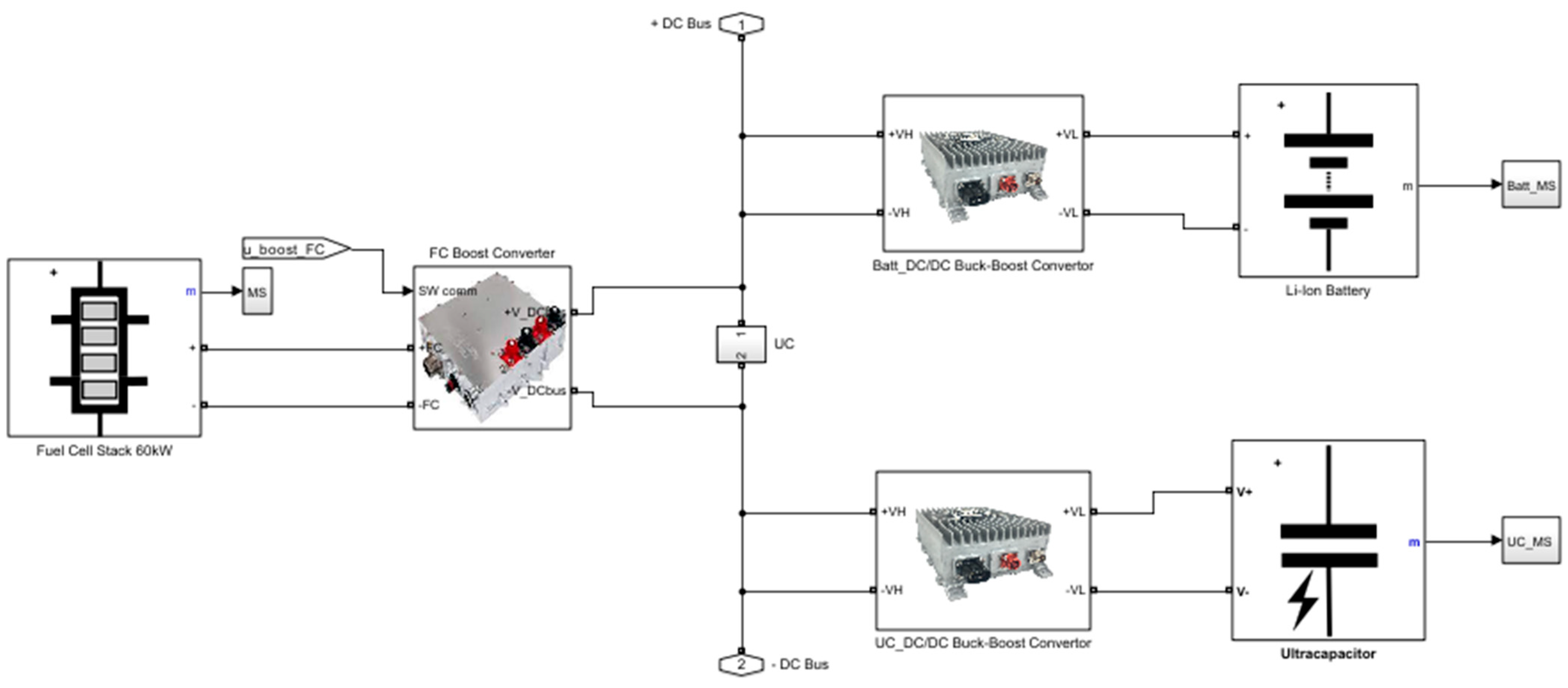

Figure 3.

Fuel cell and battery/ultracapacitor hybrid systems.

Figure 3.

Fuel cell and battery/ultracapacitor hybrid systems.

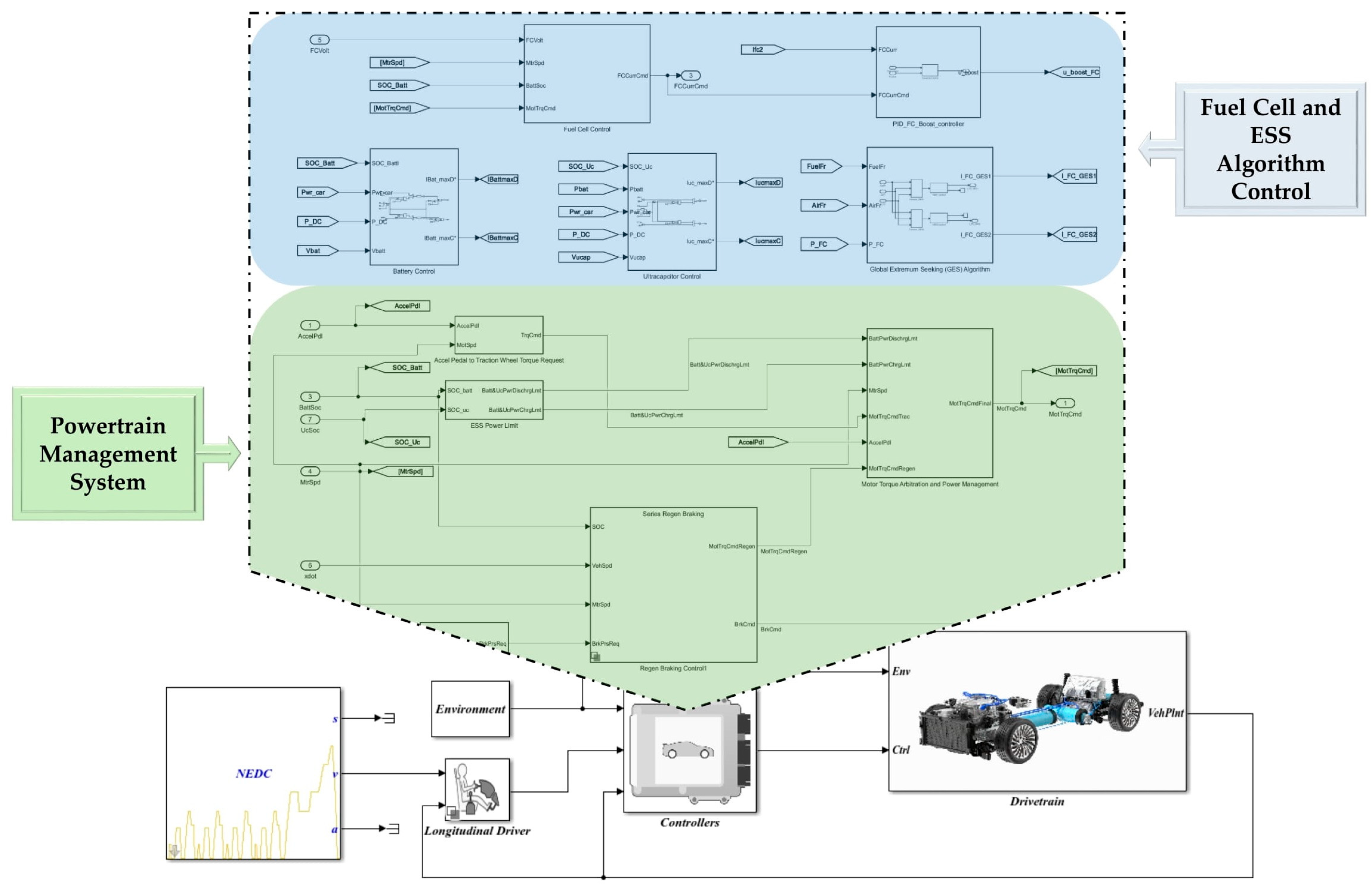

Figure 4.

Energy management and control strategy for FCHEV.

Figure 4.

Energy management and control strategy for FCHEV.

Figure 5.

SW_RTO algorithm diagram based on GES (Global Extremum Seeking).

Figure 5.

SW_RTO algorithm diagram based on GES (Global Extremum Seeking).

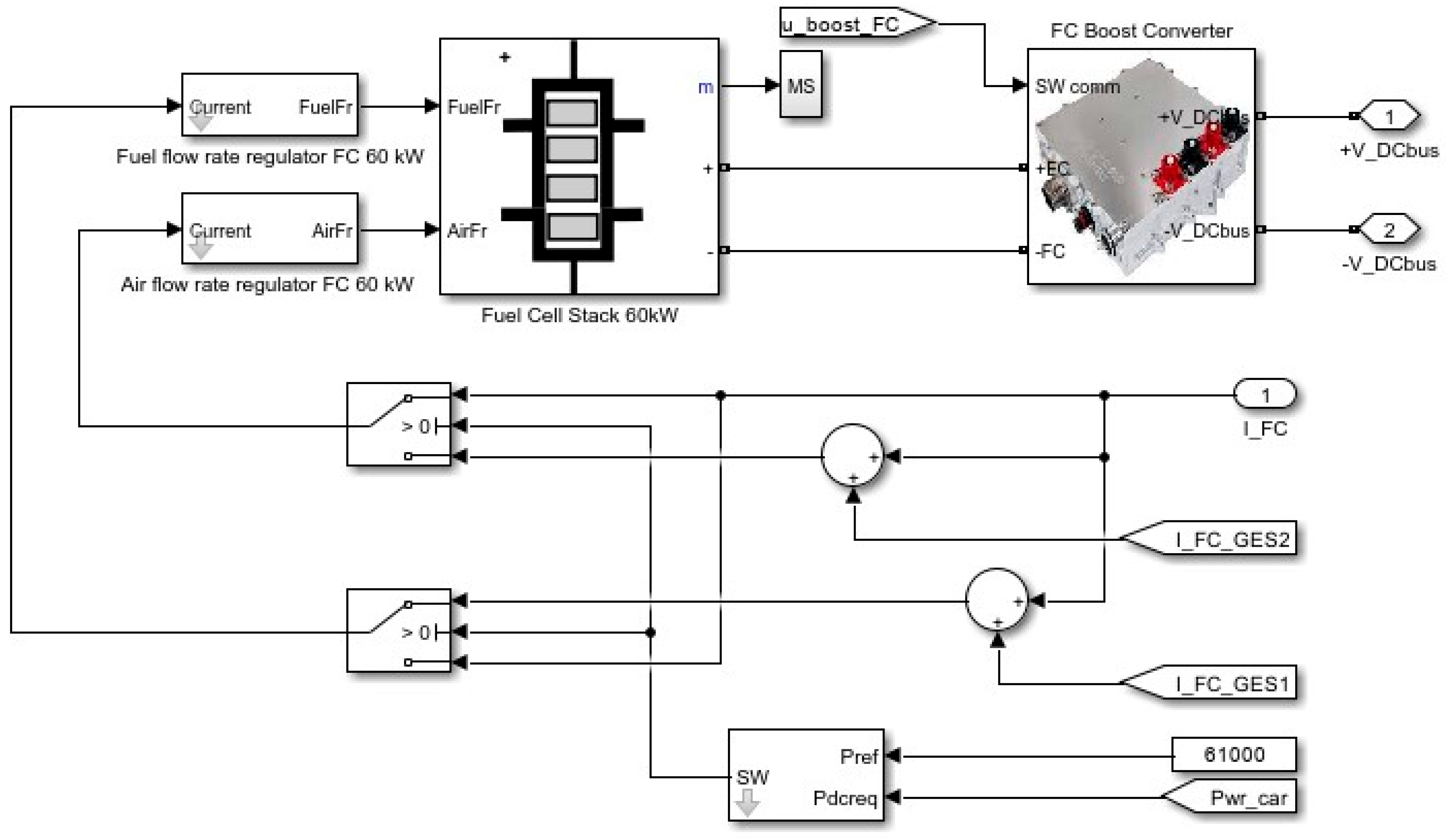

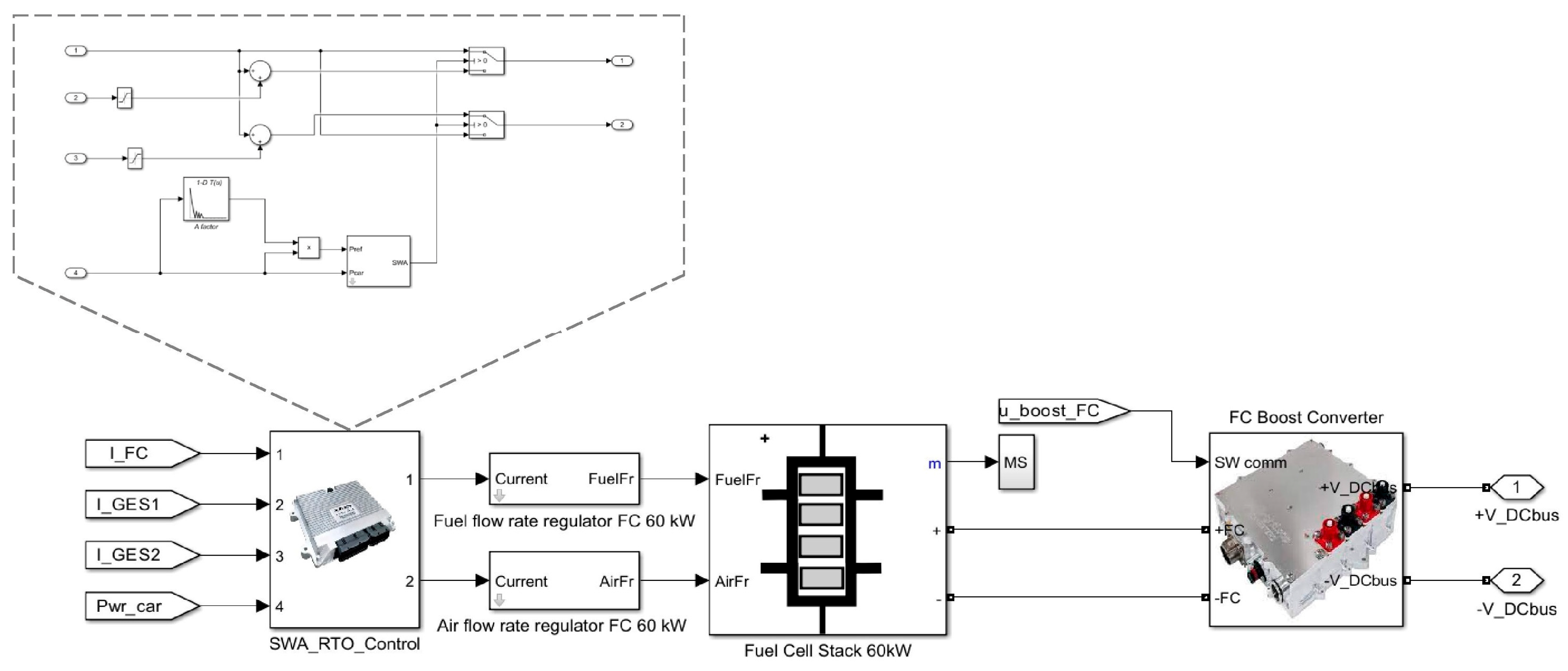

Figure 6.

SWA_RTO algorithm diagram, real-time, based on GES (Global Extremum Seeking).

Figure 6.

SWA_RTO algorithm diagram, real-time, based on GES (Global Extremum Seeking).

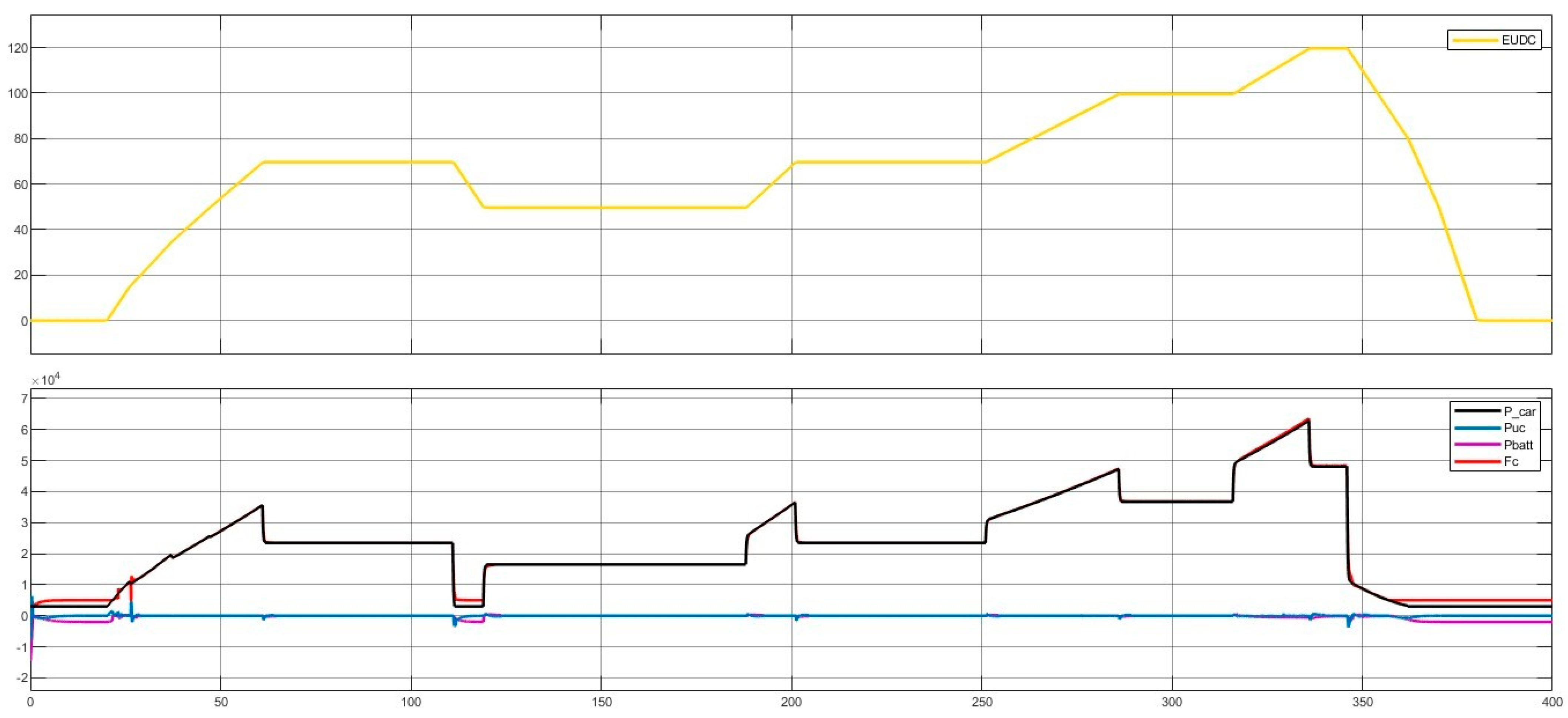

Figure 7.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 30 kW fuel cell configuration.

Figure 7.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 30 kW fuel cell configuration.

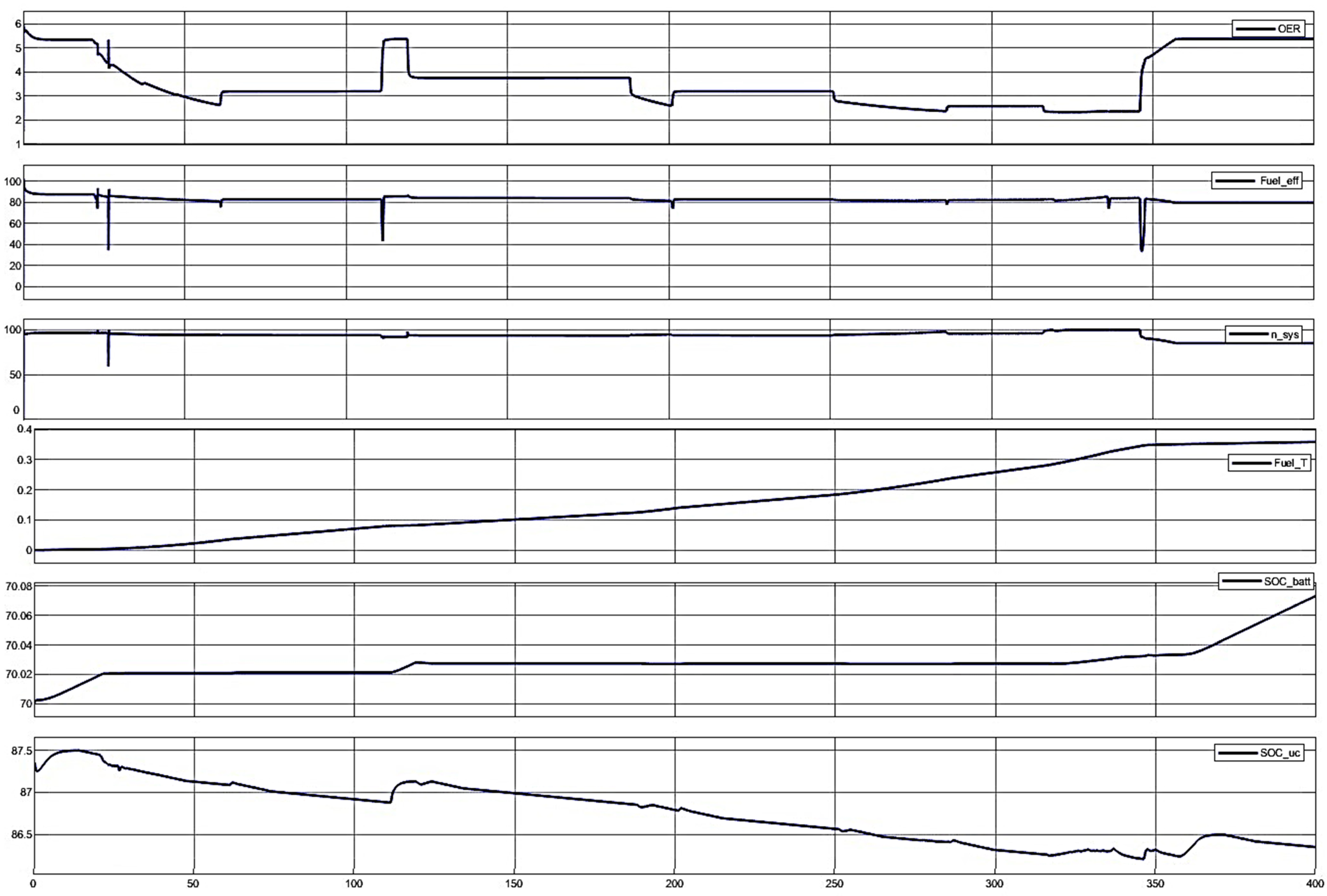

Figure 8.

Profiles of the performance indicators used (oxygen excess ratio (OER), fuel efficiency (Fuel_eff), energy efficiency (η_eff), total fuel consumption (Fuel_T), and state of charge (SOC) of batteries and ultracapacitors) in a 30 kW fuel cell configuration.

Figure 8.

Profiles of the performance indicators used (oxygen excess ratio (OER), fuel efficiency (Fuel_eff), energy efficiency (η_eff), total fuel consumption (Fuel_T), and state of charge (SOC) of batteries and ultracapacitors) in a 30 kW fuel cell configuration.

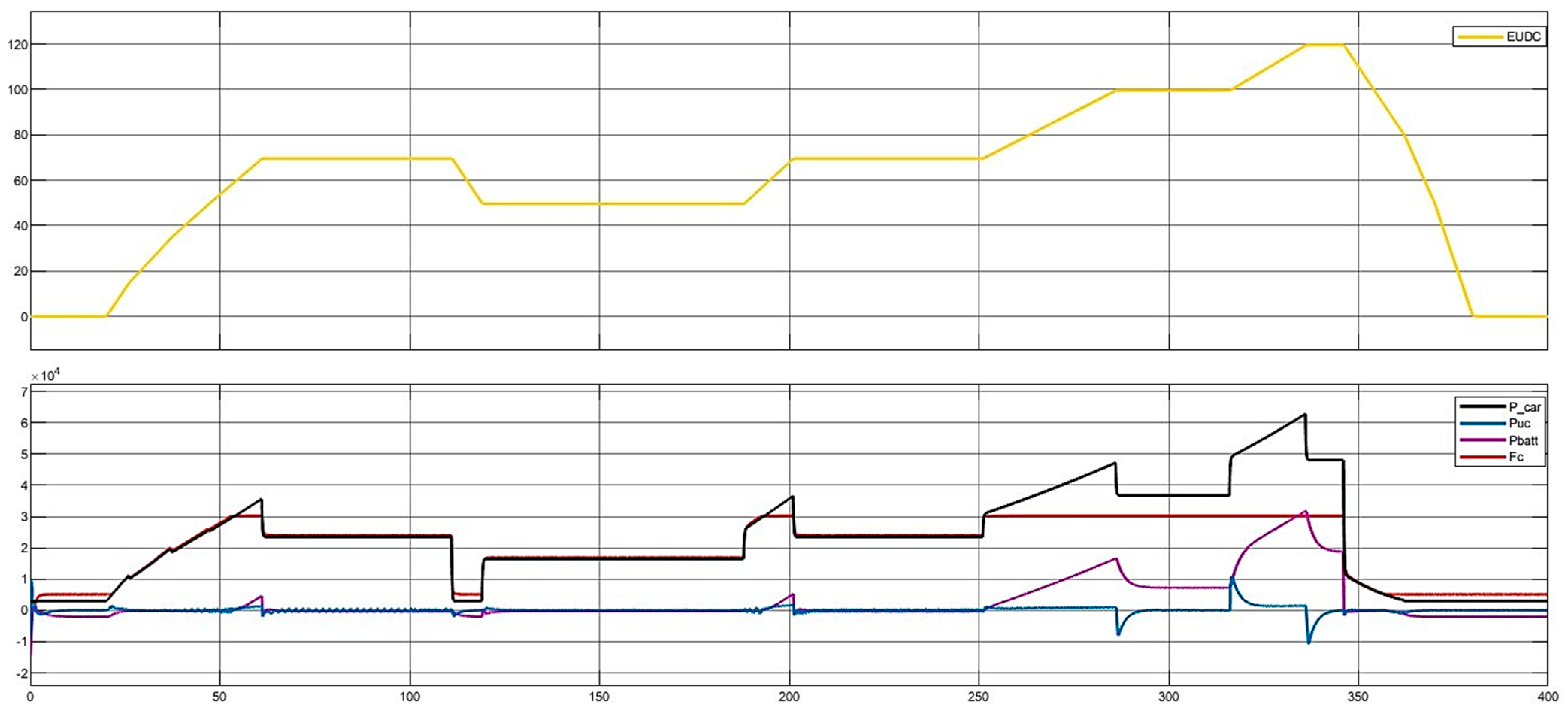

Figure 9.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 100 kW fuel cell configuration.

Figure 9.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 100 kW fuel cell configuration.

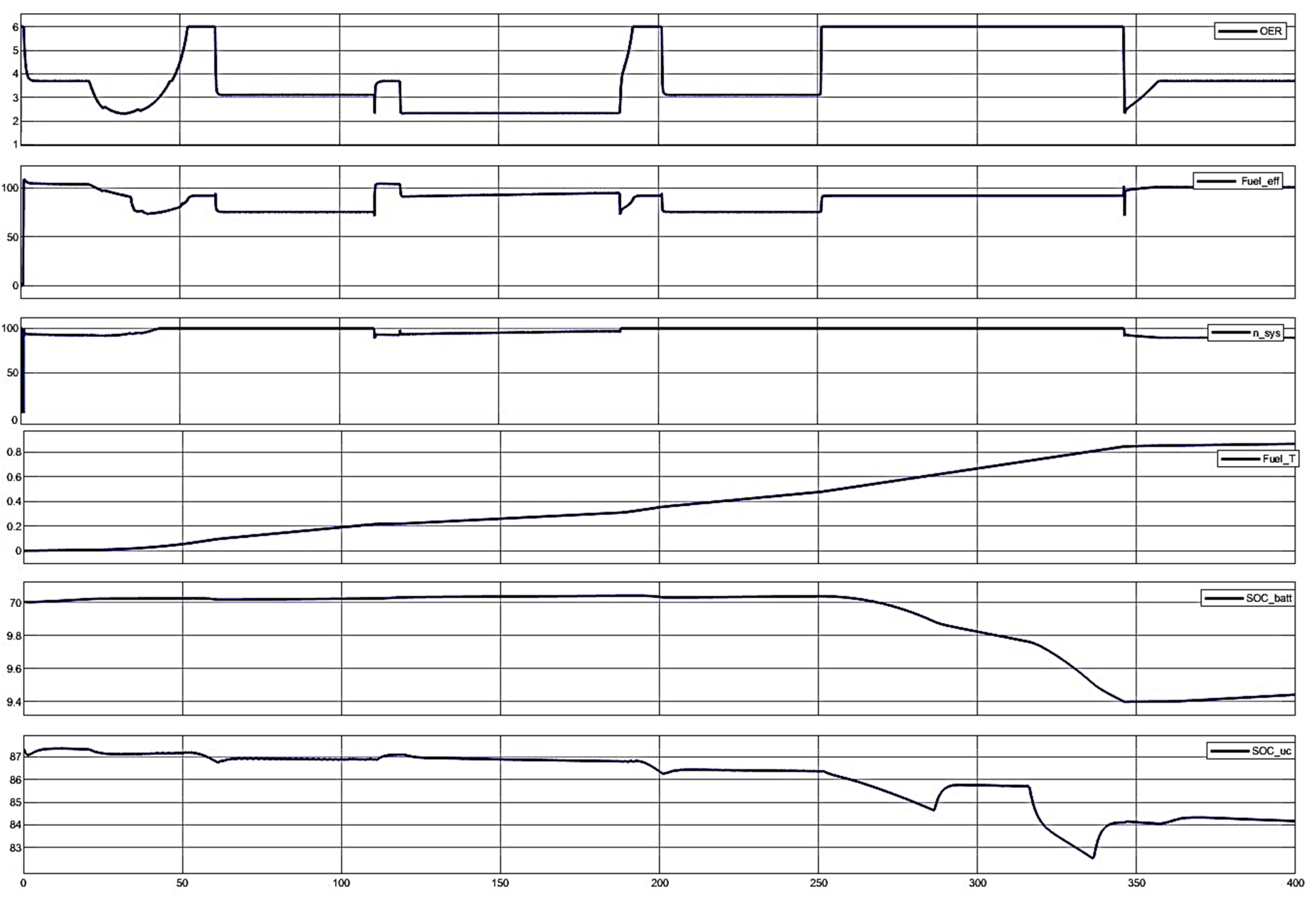

Figure 10.

Profiles of performance indicators used, total fuel consumption, and state of charge (SOC) of batteries and ultracapacitors, in a 100 kW fuel cell configuration.

Figure 10.

Profiles of performance indicators used, total fuel consumption, and state of charge (SOC) of batteries and ultracapacitors, in a 100 kW fuel cell configuration.

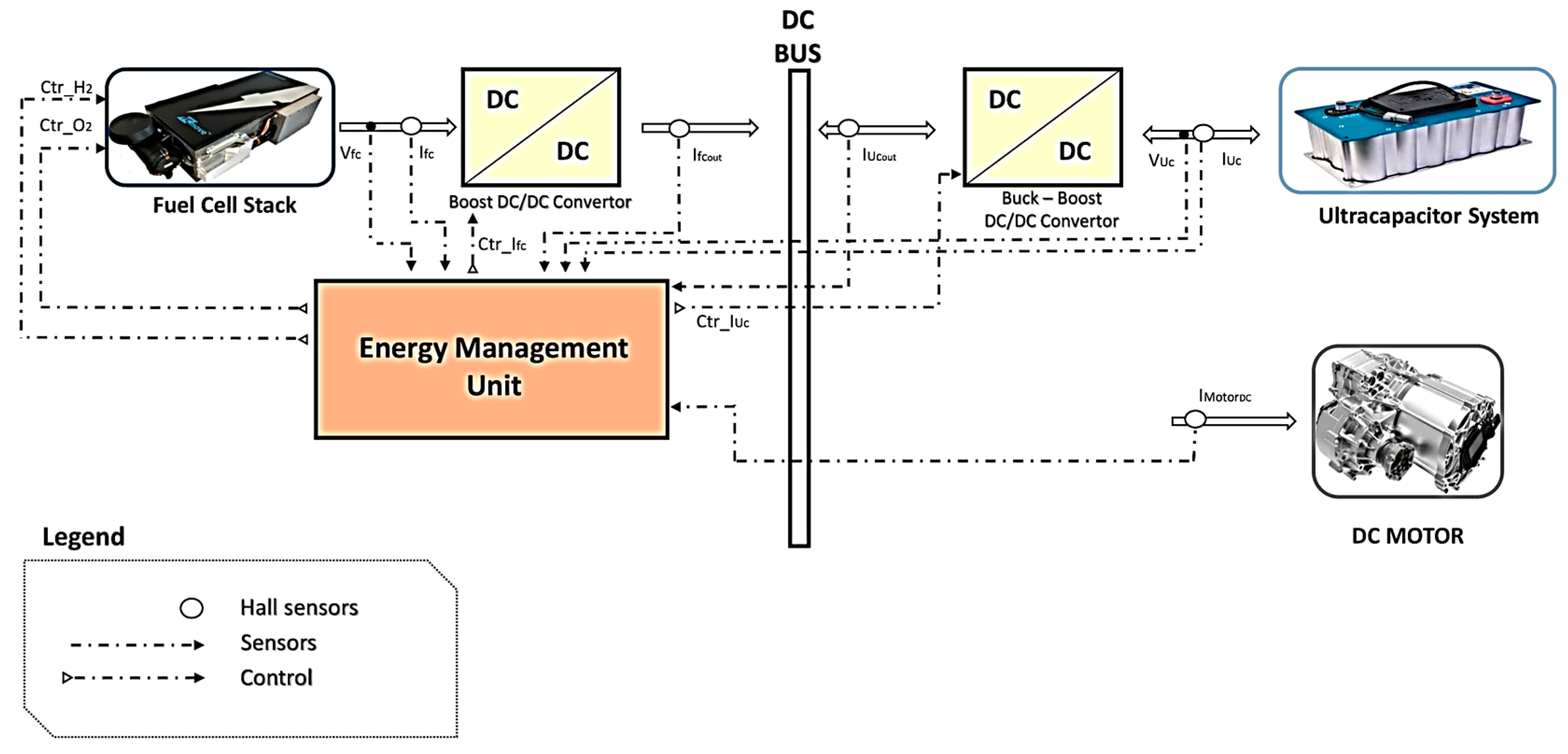

Figure 11.

PEMFC and ultracapacitor powertrain high voltage architecture.

Figure 11.

PEMFC and ultracapacitor powertrain high voltage architecture.

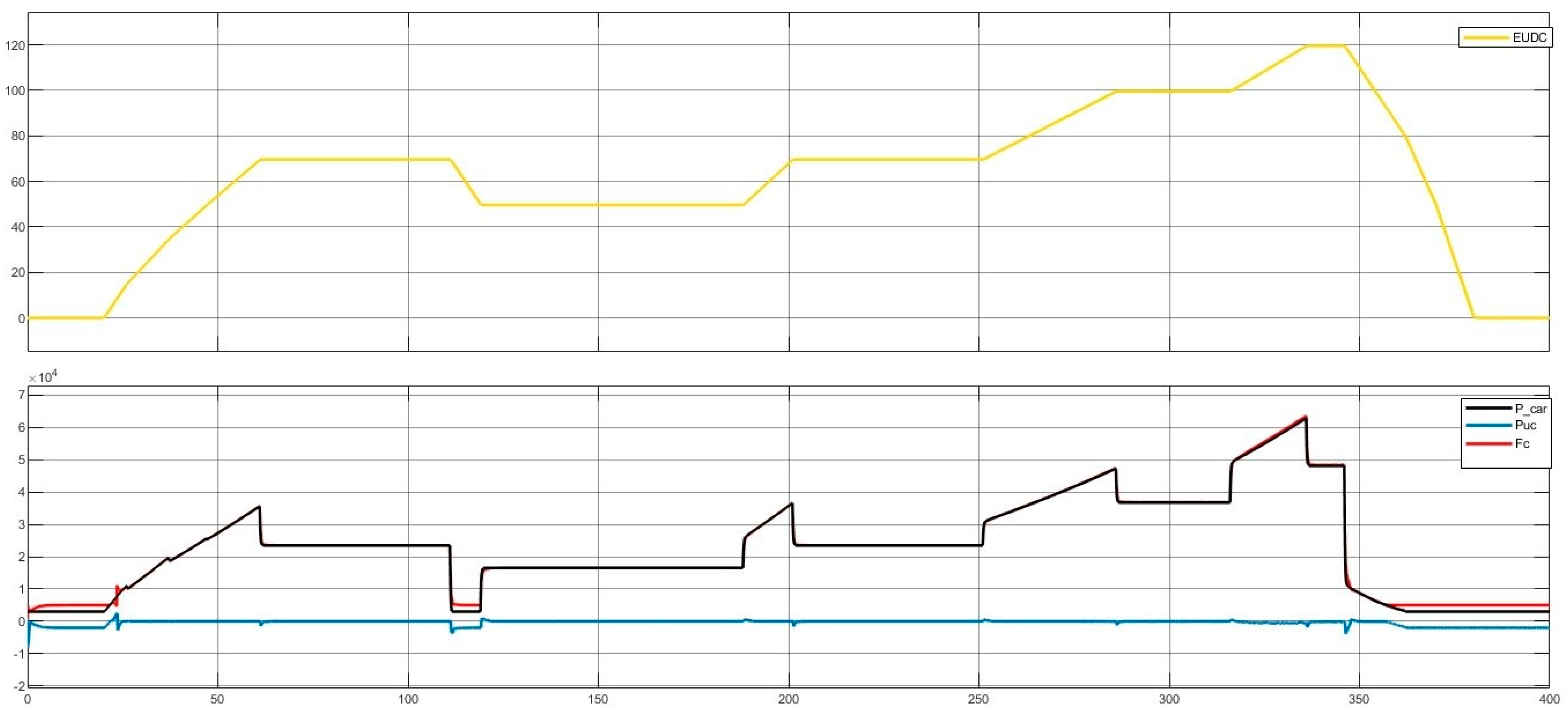

Figure 12.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 100 kW PEMFC + UC configuration.

Figure 12.

Power profiles of , , , and within an EUDC in a 100 kW PEMFC + UC configuration.

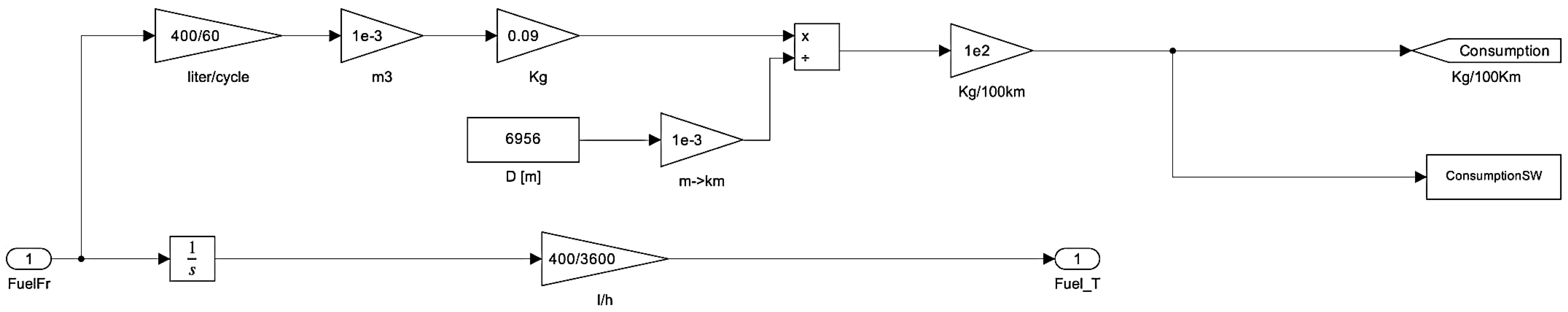

Figure 13.

Stack-condition flows conversion from LPM to Liter/h and from LPM to Kg/100 km over the entire EUDC for control strategies sFF, SW_RTO_1/2, and SWA_RTO for PEMFC + ESS configuration.

Figure 13.

Stack-condition flows conversion from LPM to Liter/h and from LPM to Kg/100 km over the entire EUDC for control strategies sFF, SW_RTO_1/2, and SWA_RTO for PEMFC + ESS configuration.

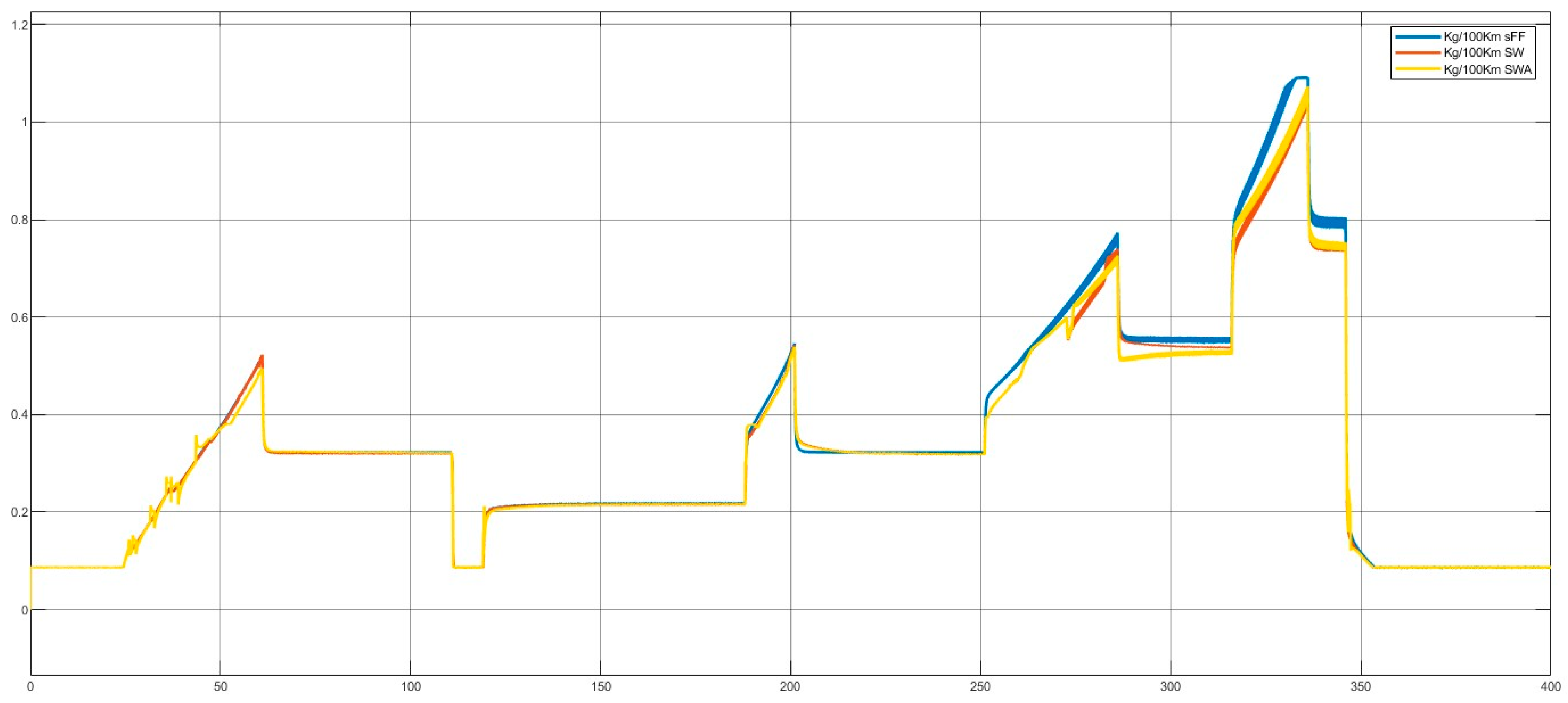

Figure 14.

Comparison of fuel consumption in Kg/100 km for control strategies sFF, SW_RTO_1/2, and SWA_RTO for PEMFC + ESS configuration.

Figure 14.

Comparison of fuel consumption in Kg/100 km for control strategies sFF, SW_RTO_1/2, and SWA_RTO for PEMFC + ESS configuration.

Table 1.

Vehicle and powertrain parameters used in 3DOF mathematical model [

27].

Table 1.

Vehicle and powertrain parameters used in 3DOF mathematical model [

27].

| Parameters | Notation | Value | U.M. |

|---|

| Total mass of vehicle | | 1500 | [Kg] |

| Horizontal distance from center of gravity (CG) to front axle | | 1.118 | [m] |

| Horizontal distance from CG to rear axle | | 1.512 | [m] |

| CG height above axles | | 0.5 | [m] |

| Frontal air drag coefficient acting along vehicle-fixed x-axis | | 0.25 | - |

| Lateral air drag coefficient acting along vehicle-fixed z-axis | | 0.1 | - |

| Air drag pitch moment acting about vehicle-fixed y-axis | | 0.1 | - |

| Frontal area | | 2.27 | [m2] |

| Rolling resistance coefficient | | 0.1 | - |

| Wheel radius | | 0.327 | [m] |

| Wheel inertia | | 0.8 | [kg m2] |

| Environmental absolute pressure | | 101,325 | [Pa] |

| Environmental air temperature | | 273 | [K] |

| Gravitational acceleration | | 9.81 | [m/s2] |

| Tilt angle | | 0° | - |

| Auxiliary power | | 3000 | [W] |

Table 2.

Longitudinal driver model parameters.

Table 2.

Longitudinal driver model parameters.

| Configuration | Type | Value |

|---|

| Control | Predictiv | - |

| Gearbox | Reverse, Neutral, Drive | - |

| Driver response time | - | 0.12 [s] |

| Safety distance | - | 4 [m] |

Table 3.

Fuel economy of RTO1, RTO2, SW_RTO_1/2, and sFF strategies in ECE-15, EUDC, and NEDC drive cycles.

Table 3.

Fuel economy of RTO1, RTO2, SW_RTO_1/2, and sFF strategies in ECE-15, EUDC, and NEDC drive cycles.

| Cycle | RTO_1 | RTO_2 |

| sFF | ∆Fuel [L/h] |

|---|

| ECE-15 | 2472.22 | 2461.11 | 2459.17 | 2467.77 | −4.45 | 6.67 | 8.6 |

| EUDC | 1721.11 | 1741.11 | 1702.22 | 1753.33 | 32.22 | 12.22 | 51.11 |

| NEDC | 8686.67 | 8853.33 | 8714.44 | 8907.77 | 221.1 | 54.44 | 193.33 |

Table 4.

Determination of vector A for the SWA_RTO strategy: stage 2.

Table 4.

Determination of vector A for the SWA_RTO strategy: stage 2.

(SWA-RTO) | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 21 | A |

|---|

| Case1 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | [20 10 5.45 4.62 0.2 0.176 3.16 2.86 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case2 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | [20 10 5.45 0.23 0.2 0.176 3.16 2.86 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case3 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | [20 10 5.45 4.62 0.2 0.176 0.158 2.86 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case4 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | [20 10 5.45 0.23 0.2 0.176 0.158 2.86 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case5 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO2 | [20 10 5.45 0.23 4 0.176 3.16 0.143 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case6 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | [20 10 0.27 0.23 4 3.53 0.158 0.143 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case7 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO2 | [20 10 0.27 4.62 4 3.53 0.158 0.143 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case8 | RTO2 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | [20 10 0.27 0.23 4 3.53 3.16 0.143 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case9 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO1 | RTO2 | [20 10 0.27 4.62 4 3.53 3.16 0.143 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

| Case10 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO1 | RTO2 | RTO1 | [20 10 0.27 4.62 0.2 3.53 0.158 2.86 0.125 0.1 0.083 0.071 0.0625 0.0555 0.05] |

Table 5.

Fuel economy for the SWA_RTO strategy, for the EUDC (t = 400 s), in Stage 2.

Table 5.

Fuel economy for the SWA_RTO strategy, for the EUDC (t = 400 s), in Stage 2.

| Case | FuelT(sFF) [L/h] | FuelT(SWA-RTO) [L/h] | ∆Fuel [L/h] |

|---|

| Case1 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

| Case2 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

| Case3 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

| Case4 | 1753.33 | 1701.11 | 52.22 |

| Case5 | 1753.33 | 1701.11 | 52.22 |

| Case6 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

| Case7 | 1753.33 | 1701.11 | 52.22 |

| Case8 | 1753.33 | 1701.11 | 52.22 |

| Case9 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

| Case10 | 1753.33 | 1700.00 | 53.33 |

Table 6.

Setting the RTO (Real-Time Optimization) strategy and the sFF (Static Feed-Forward) reference strategy for the hybrid fuel cell power system model.

Table 6.

Setting the RTO (Real-Time Optimization) strategy and the sFF (Static Feed-Forward) reference strategy for the hybrid fuel cell power system model.

| RTO Strategies | RTO_1 | RTO_2 | RTO_3 | SW_RTO_1/2 | sFF |

|---|

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

Table 7.

Parameters of the unidirectional boost DC/DC converter of the 30 kW PEMFC system.

Table 7.

Parameters of the unidirectional boost DC/DC converter of the 30 kW PEMFC system.

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|

| Input voltage | 60–110 | [V] |

| Output voltage | 400 | [V] |

| Electrical inductance | 102 × 10−5 | [H] |

| Electrical capacity | 197 × 10−5 | [F] |

| Series resistor of capacitor | 0.01 | [Ohm] |

| Converter efficiency | 97 | [%] |

Table 8.

Total fuel consumption for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 and for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

Table 8.

Total fuel consumption for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 and for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

| [kW] | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 |

|---|

| [L/h] | 7723 | 7714 | 9629 | 7902 | 8363 | 9131 |

Table 9.

Fuel economy of RTO strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

Table 9.

Fuel economy of RTO strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

| Knet = 0.5; f_ GES1 = 500 Hz; f_GES2 = 1000 Hz |

|---|

| | Kfuel | FuelT_sFF [L/h] | FuelT_RTO [L/h] | ∆FuelT [L/h] | Fueleff [W/lpm] | ηsys [%] |

|---|

| RTO_1 | 37 | 8757 | 10,170 | −1413 | 99.02 | 97 |

| RTO_2 | 37 | 8757 | 8744 | 13 | 112.4 | 98.24 |

| RTO_3 | 20; 37 | 8757 | 10,200 | −1443 | 117.4 | 96.13 |

| SW_RTO_1/2 | 20; 37 | 8757 | 7714 | 1043 | 105.9 | 96.74 |

Table 10.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF for EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

Table 10.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF for EUDC (t = 400 s) and 30 kW PEMFC.

| [kW] | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 |

|---|

| [L/h] | 1034 | 1043 | −872 | 855 | 394 | −374 |

Table 11.

Parameters of the unidirectional boost DC/DC converter of the 100 kW PEMFC system.

Table 11.

Parameters of the unidirectional boost DC/DC converter of the 100 kW PEMFC system.

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|

| Input voltage | 280 | [V] |

| Output voltage | 400 | [V] |

| Electrical inductance | 233 × 10−5 | [H] |

| Electrical capacity | 120 × 10−5 | [F] |

| Series resistor of capacitor | 0.01 | [Ohm] |

| Converter efficiency | 97 | [%] |

Table 12.

Total fuel consumption for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 and P_ref for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

Table 12.

Total fuel consumption for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 and P_ref for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

| [kW] | 11 | 21 | 31 | 41 | 51 | 61 | 71 | 81 | 91 |

|---|

| [L/h] | - | 4238 | 4132 | - | 3991 | 3970 | 3977 | 3975 | 3970 |

Table 13.

Fuel economy of RTO strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

Table 13.

Fuel economy of RTO strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

| Knet = 0.5; f_GES1 = 500 Hz; f_GES2 = 1000 Hz |

|---|

| | Kfuel | FuelT_sFF [L/h] | FuelT_RTO [L/h] | ∆FuelT [L/h] | Fueleff [W/lpm] | ηsys [%] |

|---|

| RTO_1 | 37 | 4002 | 4612 | −610 | 67.2 | 95.14 |

| RTO_2 | 37 | 4002 | 3984 | 18 | 82.7 | 94.41 |

| RTO_3 | 20; 37 | 4002 | 4614 | −612 | 66.39 | 94.84 |

| SW_RTO_1/2 | 20; 37 | 4002 | 3970 | 32 | 82.62 | 94.06 |

Table 14.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF for EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

Table 14.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF for EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC.

| [kW] | 11 | 21 | 31 | 41 | 51 | 61 | 71 | 81 | 91 |

|---|

| [L/h] | - | −236 | −130 | - | 11 | 32 | 25 | 27 | 32 |

Table 15.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF.

Table 15.

Fuel economy for strategy SW_RTO_1/2 compared to reference strategy sFF.

| EUDC | PEMFC

30 kW

| PEMFC

60 kW

| PEMFC

100 kW

| sFF

30 kW/60 kW/100 kW

| ∆FuelT

[L/h]

|

|---|

SW_RTO_1/2

| 7714 | 1702 | 3970 | 8757 | 1753 | 4002 | 1043 | 51 | 32 |

SW_RTO_1/2

| 7849 | 1701 | 4050 | 8757 | 1753 | 4002 | 908 | 52 | −48 |

Table 16.

Fuel economy of SW_RTO_1/2 strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC + UC configuration.

Table 16.

Fuel economy of SW_RTO_1/2 strategies compared to the sFF reference strategy for the EUDC (t = 400 s) and 100 kW PEMFC + UC configuration.

| Knet = 0.5; GES1 = 500 Hz; GES2 = 1000 Hz |

|---|

| PEMFC 100 kW

| Kfuel | FuelT_sFF [L/h] | FuelT_RTO [L/h] | ∆FuelT [L/h] | Fueleff [W/lpm] | ηsys [%] |

|---|

| SW_RTO_1/2 | 20; 37 | 4001 | 3985 | 16 | 82.7 | 94 |