1. Introduction

According to [

1], worldwide renewable energy sources accounted for 32% of power generation, while also representing around 80% in capacity additions in 2024. These energy sources are characterized by high volatility, which poses a significant challenge in properly balancing energy grids. In order to have sufficient electrical energy available at any time, excess energy can be stored and consumed at times of lower generation or energy consumption can be shifted to times of higher generation. Companies often have high energy demand, but also the flexibility to shift electricity consumption in a controlled manner, depending on their business processes. The adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), incl. cars, delivery vans, forklifts, trucks, buses, heavy duty machinery, etc., in the business context helps increase this flexibility in general. According to estimations of the International Energy Agency, 99% of all heavy-duty vehicle chargers will be operated at company sites with a total installed capacity of 2000 GW by 2035 [

2], emphasizing the future potential. A company that runs one or more CIs at its locations, such as production sites, warehouses, logistic hubs, distribution centers, office buildings, etc., can implement flexibility measures through the dynamic (periodic or event-triggered) determination and assignment of consumable power to each CI. The CI is typically monitored and controlled with the help of a smart charging system (SCS) that can dynamically steer, schedule, and prioritize charging processes to satisfy EV charging demand. Therefore, the SCS distributes the allocated limited power among ongoing charging sessions. It can also help safeguard the CI by properly balancing loads per phase and thus preventing fuses and transformers from being overloaded [

3,

4]. The overall efficiency of power distribution highly depends on the data available to the SCS. The required information is often stored in external systems, such as energy management systems, EV vendors’ proprietary systems, etc., and must be made accessible. To distribute power to charging sessions, the SCS prioritizes sessions based on various factors, taking into account EV and CI hardware limitations [

5,

6]. Note that in an SCS, the consumable power for EV charging can be set to a lower value than the maximum technically possible power limit in the specific CI. In addition to protecting the CI, the SCS can also contribute to cost reduction by redistributing power consumption to periods when energy prices are low. Establishing an upper limit for the maximum power available for charging at times of high energy prices results in less energy charged during that time. A company can further optimize the cost of energy for its EV fleet by estimating the respective day-ahead energy demand and purchasing energy on the market accordingly [

7]. This strategy requires not only the planning of EV charging processes for every business day upfront, but also the continuous monitoring of actual demand and the capability to change power assignments if needed.

In context of CIs, a charging plan that was created for a given day is expected to be followed until significant changes occur. For example, due to unexpected bad weather, the power demand in the morning hours can be much higher than estimated the day before because more employees would get to work by car (EV) than usual.

To mitigate such deviations in a timely manner, continuous monitoring of the demanded power is needed. However, monitoring itself can only detect issues that have already occurred: in the above example, the SCS would detect in the morning that the increase in the number of charging EVs is significantly higher than expected and try to distribute the available (limited) power among them. However, due to the higher utilization and resulting increase in energy demand, charging according to the day-ahead CI power plan is not sufficient to adequately charge all EVs. Without proper estimations about the future charging point (CP) utilization, reasonable decision making (e.g., rescheduling and energy purchasing) is not possible.

In this paper, we propose a Nowcasting approach to continuously observe and frequently, e.g., every 15 min, predict the CP utilization of a CI throughout the day. CP utilization refers to the number of active charging sessions in the CI at a given time. Nowcasting originated from meteorology and has advanced from primitive temporal extrapolation of meteorological radar and satellite imagery to advanced systems and algorithms that process data from a variety of sources [

8,

9]. In economics, Nowcasting refers to the process of forming expectations about key features of the economy, monitoring and incorporating new data releases in real time, and revising estimations whenever the realizations diverge from the initial predictions [

10,

11].

We adapt the basic idea of Nowcasting and define it in the context of company EV charging as follows: Nowcasting in company EV charging infrastructure refers to the integration of the current (“now”) system state with continuously updated short-term forecasts of key variables, such as the number of charging EVs, energy demand, or EV arrival and departure times. It provides a real-time view of anticipated near-future conditions, so-called future system states, to support timely operational decision making. In other words, Nowcasting refers to the process of describing what the system will look like in the near future based on its current state and behavior [

12]. Thereby, short-term predictions can help detect emerging trends in the CI early, for example, that the number of connected EVs starts to deviate from previously expected values. In reaction, the available power for EV charging can be dynamically adapted (increased or decreased) and cover the demand of all newly arriving vehicles. Similar approaches follow the idea of utilizing intra-day short-term forecasts in CIs. In [

13], the power demand of public charging stations for a single five-hour intra-day forecasting horizon is directly predicted. The work [

14] analyzes the use of different sliding window lengths to continuously forecast the power demand of charging stations. However, we consider the use of one-hour time horizons as too long for efficient planning during the day. A shorter period is used in [

15], which introduces rolling intra-day optimization to predict the demanded power based on 15 min slots using Kalman filters. This work makes the following key contributions:

Continuous prediction of unusual charge point utilization: In contrast to other works, our approach focuses on continuous Nowcasting of charging point utilization rather than power demand, providing updated predictions every fifteen minutes to capture emerging or unusual utilization trends during the day.

Experiments for short-term adaptability: We continuously predict eight horizons for the next two hours by applying multi-horizon forecasting techniques and use different weighting strategies to prioritize the most recent observations to adapt to unusual patterns.

Evaluation based on real-world datasets: The proposed approach is evaluated based on data from a real charging infrastructure. Data is divided in two datasets to validate performance on regular and irregular patterns, measured with RMSE and MAE.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we describe the research methodology and dataset (DS) that we have used.

Section 3 defines requirements, covers our technical approach to periodically predict the number of used charging stations within a CI, and discusses major findings. In

Section 4 experimental results are presented and discussed. Finally, in

Section 5 we draw conclusions and outline next steps.

3. Nowcasting Concept in the Context of EV Charging

3.1. Requirements Overview

We consider the following requirements important for the calculation and integration of short-term forecasts in EV charging systems. Note that numbering is only provided for referencing purposes and does not imply any order of importance.

Requirement 1—Suitable forecasting frequency and horizon: Predictions about the future status of the CI are enablers of efficient management procedures during the day, incl. planning of charging sessions, limiting charging power for charging stations, etc. We consider a forecasting horizon of two hours in advance with a prediction recalculation frequency of 15 min as suitable. The forecasting horizon of two hours is selected as a compromise between prediction accuracy, as forecast reliability tends to degrade over time, and a sufficient (re-)planning period for related decision making. A two-hour forecasting horizon is long enough to take measures against a detected, unusual intra-day trend, e.g., a higher number of connected EVs than is typical at the given time of the day. The selection of a 15 min forecasting interval is aligned to the typical interval for updating energy prices in intra-day energy markets.

Requirement 2—Real-time integration and computation time: Short-term predictions require the gathering of relevant data in near real time, fast computation using prediction models, and a fast subsequent decision making process as well. In the case of a CI, the time from detecting a trigger event to the roll-out of an updated charge plan assigned to the charging stations should be minimized.

Requirement 3—Adaption to dynamic usage patterns: Prioritizing the most recent data enables adaptation to intra-day usage patterns that deviate from regular behavior, e.g., as a result of changing weather conditions, special events, holidays, traffic congestion, etc. Assigning higher weights to more recent data has the effect of biasing the prediction models towards recent data. This decreases the influence of outdated patterns, and predictions can adapt to intra-day short-term trends more accurately. However, an overly aggressive weighting strategy can result in the exclusion of significant long-term patterns. In the case of the CI belonging to a company with regular daytime working hours, it can be beneficial to weight data points that belong to the specific working day. If the company location operates continuously, for example a 24/7 logistics hub, day-specific patterns could be of less significance. In this case, it may be more beneficial to set a fixed number of the most recent data points to be weighted.

Requirement 4—Fast model adaption and deployment: Using a limited amount of input data for prediction leads to reduced training and deployment times as well as fast model updates for real-time adaption. It allows companies to quickly deploy and iterate on forecasting solutions without the need for extensive historical data collection. In addition, using only a few weeks of historical data further helps capture the most recent intra-day patterns.

Requirement 5—Intrinsic system data usage: Including all relevant information, such as weather, traffic, employee schedules, and special events, results in dependencies on external systems and need for extensive data pre-processing. By relying solely on (local) data available in the SCS, the robustness of the system increases as dependencies on external systems are minimized. In addition, there is no need to deal with unavailable or incorrect data from external sources.

3.2. Approach to Increase the Significance of the Most Recent Data Points

Short-term forecasts are used to predict

n data points in the near future based on periodically captured past data points of an existing time-series dataset, as shown in

Figure 3.

Note that a data point can represent a single system parameter, but also a collection of different measurement values at time , such as the number of ongoing charging sessions, the power drawn, the total capacity of charging EVs’ batteries, etc. The equidistant data points with contain data about p past system states captured at , whereas the data point represents the latest (current) known state at . The data points with are future data points to be predicted according to the selected frequency. In a practical setup, for example, with min, , and , the 120 latest data points (captured in a ten-hour time-frame) would be used to predict the next four data points occurring within the next twenty minutes.

In order to increase the significance of the most recent data points for the predictions, weights () are computed and assigned to the m most recent data points () such that will be weighted with the corresponding value.

The applied weighting ensures that newer data points have a greater influence on the prediction of the next few future data points compared to older data points. The underlying basic assumption is that a CI behaves as an inertial system with regard to parameters, such as the number of ongoing charging sessions: The duration of charging sessions is relatively long compared to , and it is likely that only a small number of EVs arrive or depart within the next few observation/capturing periods.

We consider the following weighting schemes to determine and assign weights to m selected past data points.

The linear (L) approach, illustrated by one possible implementation in Equation (

1), assigns weights that linearly increase for more recent observations, see also

Table 1.

The squared (S) approach, illustrated by one possible implementation in Equation (

2), quadratically increases the weights of data points, leading to a higher weight for the most recent observations compared to the linear approach, see also

Table 1.

The exponential (E) approach, illustrated by one possible implementation in Equation (

3), increases the weight of data points much more aggressively, see also

Table 1.

The growth rate

is set based on the number of data points to weight by adapting the parameter

q. Parameter

m represents the number of data points selected for weighting. This ensures that numerical overflow is avoided when weighting a full day. At the same time, it ensures a higher weight for the most recent data point than the other approaches, even for small numbers of

m, as shown in

Table 1.

In models that allow the application of weights to single data points using the

parameter, weights can be incorporated to adjust model training accordingly. In addition, weights can be incorporated by using the weighted moving average (WMA) as an additional input feature. If required, the weights can be dynamically adjusted based on the performance of the prediction model [

19,

20].

denotes the WMA at the current time index , based on the most recent m observations. It is computed using the values for , where each point is assigned a weight based on the selected approach (see L, S, and E above) for weighting. The weighted sum is then normalized by the sum of the weights. For example, if , the weighted moving average at the current time index is computed using the most recent eight data points: .

3.3. Multi-Horizon Strategies to Predict Future Data Points

To predict a selected number of future equidistant data points with a given frequency (e.g.,

min), we examine different strategies [

21,

22].

The strategy Single-Step computes a specific future data point by indirectly considering all past data points that were used to train the prediction model, as shown in

Figure 4. The prediction model itself remains static; i.e., there is no retraining applied.

In multi-horizon forecasting strategies (see

Figure 4), multiple subsequent future data points are predicted at the same time. Thereby, the model can use previously predicted data points as input data (together with known past values) to predict further future data points. As an alternative, predicted values can be added to the training dataset for retraining before executing the next prediction. We consider the following four multi-horizons strategies:

Direct: An independent model for each prediction horizon is trained by using already known past observations as the training dataset. The approach helps minimize prediction errors for the target value at the specific horizon. The main disadvantage is the increasing training effort with an increasing number of prediction horizons.

Recursive: Here, a single model is trained that uses previously predicted values as input during inference to generate multi-horizon forecasts. For short-term forecasting of unusual, volatile changes in the number of active charging sessions, we do not use the strategy Recursive as it is prone to error accumulation and may fail to adapt to evolving patterns in the predicted values.

Direct–Recursive (DirRec): It combines the advantages of Direct and Recursive by training independent models for each forecast horizon, as in the strategy Direct, and by incorporating previous predictions as inputs during inference, as in the strategy Recursive [

23].

Multi-Input–Multi-Output (MIMO): To mitigate stepwise error accumulation, MIMO predicts a single output vector containing multiple future data points based on the latest observed data points. Another advantage of this strategy is that only one prediction model needs to be trained upfront.

3.4. Model Selection and Optimization

To detect short-term changes, we predict the number of connected EVs and address the requirements defined in

Section 3. To satisfy Requirement 1, we apply the multi-horizon forecasting strategies Direct, DirRec, and MIMO in our experiments (see

Section 3.3). A fixed horizon of two hours divided into 15 min intervals, corresponding to eight predicted equidistant data points, is used to validate these strategies and fulfill Requirement 2. Furthermore, we address Requirement 3 by applying the proposed linear, squared, and exponential weighting schemes to increase the importance of the most recent data points (see

Section 3.2) and adapt to dynamic usage patterns. The selected weighting scheme is based on data points of the current day, meaning that the number of data points to weight increases with every prediction horizon until the end of the day. To address Requirement 4, we evaluate fast model adaption and deployment by evaluating the impact of input data limited to data points from two and four weeks. Following Requirement 5, we only use the timestamp and an integer representing the number of active charging stations as the input dataset.

We use XGBoost and LSTM to generate short-term predictions in our experiments. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is used as it offers strong performance for the training of multiple models, as required in multi-horizon strategies such as Direct and DirRec. It is further extensively used and recommended in the literature to capture short-term changes [

24,

25]. LSTM is selected because of its design to capture temporal dependencies and sequential patterns and its common use in predictions related to forecasting in the area of EV charging, as shown in an overview of different forecasting methods [

26]. Feature selection and hyperparameter tuning are optimized and validated using a one-week test set and a rolling window approach with the strategy Single-Step. The only source for additional feature extraction is the timestamp associated with each data point. For the XGBoost model we use features that include lagged values (

,

,

, and

), time-based cyclical encodings (

,

,

, and

), and the binary indicator

. Features for LSTM are normalized, and the cyclical nature of temporal features is addressed by a sine and cosine transformation. They include the target variable

, time-based cyclical encodings (

,

,

, and

), the flag

, and the weekly lag

. All features are scaled to the range

.

Both models are trained using the Adam optimizer with mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. Hyperparameter optimization is performed with Optuna, and the results are shown in

Table 2. Parameters are optimized for each combination of XGBoost and LSTM with each dataset. Due to the different

, using eight instead of one for the strategy MIMO, additional parameters are used. Note that for LSTM, we set

based on findings in [

27].

Following the optimization phase, the validation data is processed using a rolling window to implement the multi-horizon strategies. For XGBoost, the proposed time-dependent weighting schemes are applied by computing a weight for each training instance based on the data point of the current day. These weights are then integrated into the training process via the

parameter to increase the importance of the most recent patterns. While it introduces additional computational overhead, the short input sequences and the efficiency of XGBoost make this approach feasible for applying dynamic weighting schemes. However, XGBoost is not included in the evaluation of the strategy MIMO because it is designed for single-target regression. In contrast, LSTM requires more training time. Therefore, we included our weighting strategies by adding the WMA as a feature, as described in

Section 3.2. This allows training of the horizon-specific LSTM models once at the start of the test phase, instead of at every time step, to reduce computation time.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Results

As expected, experimental results indicate a decline in prediction accuracy with an increasing forecast horizon.

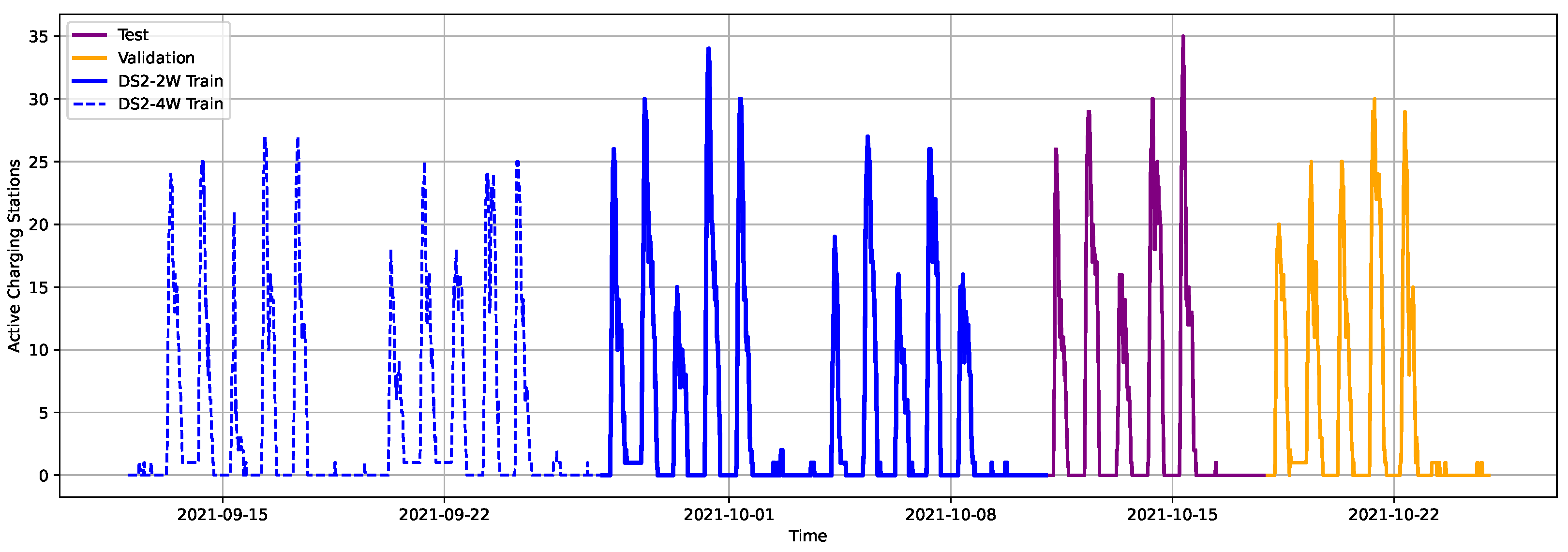

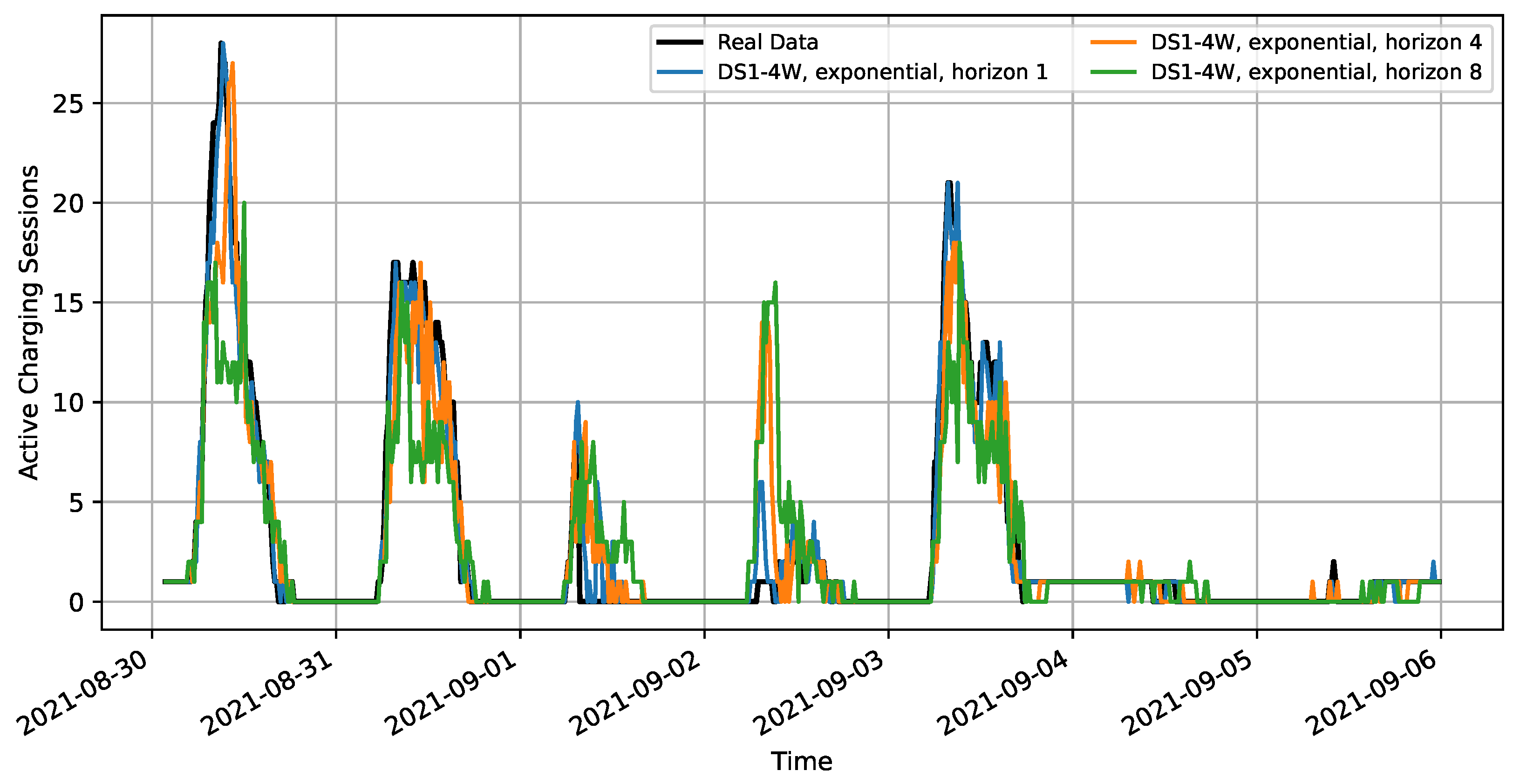

Figure 5 shows the predictions of the XGBoost model for a full week, generated using exponential weighting and the strategy Direct applied to DS1-4W.

To enhance the visibility of single prediction horizons, only horizon 1 (15 min), 4 (1 h), and 8 (2 h) are displayed. An example of the adaption to intra-day trends in the most recent data is Monday, 30 August, a day with significantly higher utilization than usual. This case illustrates the impact of short-term forecasting under atypical conditions, showing the influence of past patterns in the more distant horizons. The closer a future data point is, the better the model adapts to the ongoing trend. Predictions of more distant future data points tend to revert toward the typical utilization patterns in the training data. A similar pattern is observed on the next day, in which the utilization remains high for longer than usual. On Thursday, 2 September, the pattern is reversed, with significantly fewer charging sessions than usual. Initial forecasts reflect typical usage patterns, but as new data points are included, predictions are adapted to the new pattern by predicting lower utilization of CPs. Performance of peak periods, such as Monday, 30 August shows that especially close horizons can be predicted by the model. Off-peak charging periods, such as nights and weekends, show some noise but a relatively low absolute error, e.g., the prediction of single EVs on weekends.

Figure 6 illustrates different prediction horizons on Monday 30 August, generated by the LSTM model using linear weighting and the multi-horizon strategy Direct applied to DS1-4W. As noted earlier, utilization on that day exceeded typical levels. Predictions capture the higher utilization trend, estimating higher than usual utilization for the day. However, predictions for later horizons gradually return towards typical lower utilization levels.

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the performance of the LSTM and XGBoost models across all datasets, using the strategy Direct in combination with exponential (E), linear (L), and square (S) weighting schemes. Values of RMSE and MAE for horizons between

Table 3 and

Table 4 generally increase linearly for each horizon. Results of both tables show that the first forecasting horizon of XGBoost trained on DS1-2W with two weeks of data results in a slightly better RMSE than forecasts trained on DS1-4W with four weeks of data. In contrast, for the datasets containing regular business weeks, the opposite is the case. The four-week training set DS2-4W has better RMSE values for all weighting schemes than DS2-2W. For LSTM, the opposite trend is observed for both collections of the datasets.

Table 3 shows the RMSE and MAE for the fifteen-minute horizon using the strategy Direct. The best result is achieved for DS1-2W by XGBoost with the linear weighting schema in both RMSE (0.906) and MAE (0.355). This is interesting, as DS1-2W has an unusual validation week (see

Section 2.2) and only two weeks for training. This may be because the shorter training period, being closer to the validation week, better captures recent pattern shifts and fluctuations present in the validation data. In addition, the smaller metrics for the first dataset may be a result of the absolute range, with DS1 containing lower CP utilization than DS2. Furthermore, a reason for the linear weighting schema yielding the best results could be that nonlinear weighting decreases the importance of older data points too much.

Table 4 shows that XGBoost also performs better at the two-hour prediction horizon. Additionally, DS2-4W performs best, indicating that the more regular dataset and longer training window lead to the most accurate long-horizon forecasts. The best RMSE of 2.454 is achieved by XGBoost trained on DS2-4W with exponential weighting and the best MAE of 1.230 on the same dataset with squared weighting. This indicates that a higher importance of the most recent data points is beneficial to predict evolving trends in later horizons.

Table 5 shows the performance of the LSTM and XGBoost models across all datasets, using the strategy DirRec. A special measure is the high RMSE of the XGBoost model on DS2-2W with exponential weighting. This value might be the result of accumulated errors in the last horizon on Thursday morning, where each overestimation adds exponentially to the next, leading to predictions that are significantly too high. Overall results are comparable to the strategy Direct (see

Table 4) but slightly worse. The best RMSE of 2.608 was achieved by XGBoost trained on DS2-4W using linear weighting, and the lowest MAE of 1.256 was achieved by LSTM trained on DS1-4W with linear weighting. Achieving the best results with the linear weighting schema indicates that it stabilizes the recursive feedback loop of the strategy DirRec. Both strategies performed better than the strategy MIMO. The best results of the strategy MIMO achieved an RMSE of 3.142 for the first horizon using a linear weighting schema for DS1-2W and an RMSE of 3.309 for the last horizon with a linear weighting schema for DS2-2W.

The overall best performance based on RMSE is achieved from the XGBoost model utilizing the strategy Direct with linear weighting of the most recent observations. The better performance of XGBoost in contrast to LSTM could be the result of the input data. Data for training only contains up to four weeks of training data, limiting the ability of LSTM to capture temporal patterns.

4.2. Usage and Impact of Short-Term Predictions in Charging Infrastructures

To better understand the usage and potential impact of Nowcasting in CI operations, consider the following scenario: A company operates a CI at one of its production facilities with 20 charging points, each with a maximum output power of 11 kW. The CI is basically power-constrained; the maximum allowed power limit is set to 200 kW to ensure the operational safety of other assets, including production machinery, buildings, offices, etc. The company purchases energy on the day-ahead market and thus it needs to estimate the demanded power for each 15 min time slot during the next day. Concerning the CI’s demand, an important parameter for the estimation is the number of active charging sessions during the day, i.e., how many cars could be charged simultaneously in each time interval. The company expects, for example, a peak of up to 10 charging EVs in the morning and 15 EVs in the afternoon hours. Another aspect is the volatile cost of energy. In the example, the energy supplier announced higher prices per kWh in the morning hours compared to the lower prices in the afternoon. In response, as shown by the black dashed line in

Figure 7, the company sets the CI’s power limit to 100 kW for roughly the first half of the working day and plans to increase the limit to 200 kW around noon. As illustrated by the blue dotted curve, the expected number of charging EVs could consume a higher amount of energy in the morning hours than actually allowed. Therefore, energy costs will be lower, but at the same time not every EV would be charged sufficiently. In the afternoon, thanks to the higher amount of distributable power, the situation can improve, especially when many EVs stay long enough at the charging points. This load-shifting measure seems to be adequate and feasible if the number of charging EVs was estimated well on the day before.

However, such an approach lacks the ability to react to changes that occur during execution and may result in inadequate charging of EVs in cases with deviation from the expected daily pattern. For example, a customer event can lead to a higher number of EVs than expected, e.g., up to 15 EVs charging in the morning and 20 EVs in the afternoon.

The blue dotted curve in

Figure 8 illustrates power consumption that would occur in the absence of power restrictions on a day with higher CP utilization than expected. The power demand on this day is slightly higher than usual, and the decrease at lunchtime is less pronounced. The red curve shows the power needed to compensate the previously undelivered energy resulting from earlier power limitations. When EVs depart in the afternoon, less energy than required is delivered, so EVs leave with insufficiently charged batteries. To minimize energy that could not successfully be shifted (see the white area between the red and the blue curve), it is essential to identify deviations from the planned charging schedule at an early stage. With our experiments, we have shown how to identify such short-term changes. For each predicted future data point, we calculate the difference between the estimated day-ahead CP utilization and the predicted number of charging EVs at the current time (now). The deviations observed in the predicted data points (in our case

within a two-hour forecast horizon) indicate that the actual number of connected EVs diverges from the estimates. For example, in day-ahead planning a morning peak of 10 connected EVs was expected, but at 9 a.m. intra-day predictions indicate a peak of up to 15 EVs in the next two hours. The new information is then included in decision making for further power planning, e.g., to re-adjust the maximum available and thus distributable power for charging. We assume that adjusting the CI power limit constitutes a necessary precautionary measure, as deviations from the planned charging power can lead to the emergence of more costly scenarios. In the case of a lower than expected trend, the company needs to distribute excess energy bought the day ahead by increasing the power consumption of other local assets; otherwise it may pay fines to its energy provider. If the identified demand is higher than expected earlier, like in our scenario, the company can decide whether EV charging under the new conditions is still sufficient or an adjustment to the power limit is required. Without appropriate adjustments, situations may arise in which insufficiently charged EVs require an additional stop for recharging during their next trip, potentially leading to missed delivery deadlines or preventing employees from attending important customer appointments. To prevent such cases in the proposed scenario,

Figure 8 shows the adjustment by increasing the power limitation earlier than originally planned, as shown by the green dashed curve. As a result, the available power is now distributed more effectively among active charging sessions, enabling a greater amount of energy to be delivered throughout the day and ensuring higher SoC values of departing EVs. Possible measures a company can take to increase the available power for EV charging include reducing the power consumption of other local assets or purchasing additional energy from its energy provider.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we proposed a Nowcasting approach to adapt to unusual trends in a CI by generating short-term forecasts to predict the number of occupied charging stations. To improve responsiveness to recent changes, we introduced linear, squared, and exponential weighting schemes. For multi-horizon forecasting, we employed the strategies Direct, DirRec, and MIMO, each designed to produce multiple forecasts across different future horizons. Experiments with LSTM and XGBoost indicate that forecasting up to 2 h ahead is beneficial. Results show that the strategies Direct and DirRec perform better than MIMO, with Direct being slightly better than DirRec. The best RMSE of 0.906 for the 15 min horizon is achieved with XGBoost using the strategy Direct with a linear weighting schema for DS1-2W. Similarly for the 2 h horizon, the best RMSE of 2.545 is achieved with XGBoost using the strategy Direct, but with an exponential weighting strategy. This indicates that more aggressive weighting is preferable for predicting later horizons. However, we intend to explore whether reducing the time interval between data points to, for example, five minutes remains computationally feasible. Finally, we outlined how these forecasts can be integrated into company decision-making processes and discussed their potential advantages in real-world applications.

Future work includes several directions to further evaluate and enhance our approach. For instance, we plan to assess the impact of expanding the input data scope, such as by incorporating data spanning multiple months. In addition, further investigation into the generalization of the proposed approach to other charging infrastructures or regional charging networks is planned. We also aim to validate our assumption that aligning the data split with business weeks leads to better performance than conventional percentage-based splits. Additionally, we intend to investigate the effect of varying the number of data points used in the weighting schemes. Specifically, we will compare our current approach of applying weights dynamically to data points within the same day, with fixed-length windows, such as using data points from the last four or eight hours. Furthermore, we plan to implement and adapt the approach in simulation environments to enable real-time forecasting as EVs arrive at or depart from the CI. Integrating data as soon as it becomes available, such as the detection of an arriving vehicle, is crucial to further develop the Nowcasting approach.