3. Infrastructure Risk Points

Locations and situations where autonomous vehicle navigation fails are often cited as additional challenges to fully autonomous driving. These include road conditions (deteriorated, e.g., no lane markings, undefined lanes, potholes, mountain and tunnel roads where direction signals are not very clear), weather conditions, traffic conditions (other autonomous cars on the road, people breaking traffic rules, random objects, unexpected conditions), and radar interference. In general, these locations are some of the first places where virtual track in any form would be most effectively applied.

Another challenge may lie in the behavior of surrounding vehicles, as empirical analyses suggest that driver interactions (or control algorithms) are not limited to short-range influences. Decision-making in saturated traffic is affected by at least two immediate predecessors, while under lower traffic density, the influence may extend to four or five vehicles ahead. This effect diminishes with increasing density. These findings support the hypothesis of medium-range interactions, which are relevant for the design of robust guidance systems and accurate trajectory prediction [

7].

When examining the specification of short- and medium-range distances more closely, their definitions vary considerably. In the study by [

7], these ranges are not defined in metric or temporal units but rather indirectly through the number of preceding vehicles—typically two vehicles for short range and up to four to five vehicles for medium range of interaction. In contrast, other traffic studies [

8,

9,

10] commonly quantify short range as a time gap below 1.5 s or a distance up to 10–15 m, whereas the medium range corresponds approximately to 30–50 m or 2–5 times the vehicle length within the traffic flow.

Infrastructure elements affecting accuracy:

Bridges and viaducts;

Tall buildings (urban development, urban canyons);

Tunnels;

Dense tree canopy;

Industrial and warehouse buildings

Corridors and roadways cut into the terrain;

Noise barriers;

Large parking lots and garages;

Overhead high-voltage lines;

Other transportation infrastructure with reflective surfaces.

All these locations have been identified as places where GNSS is completely absent or shows high error rates. The multipath effect occurs when the GNSS satellite signal reaches the antenna by paths other than the direct line of sight (LOS), typically after reflecting off another object. Two different types of multipath propagation can be defined. In the first case, both the direct signal and one or more reflected signals are received. In the second case, the direct signal is completely blocked, and the receiver tracks only the reflected signal or signals.

Another place where the virtual track can be effectively applied is at intersections, especially grade-separated or complex intersections. At grade-separated intersections, due to overpasses and underpasses, the multipath effect will occur, making the use of the virtual track as beneficial as in areas with missing GNSS. A similar use would be the implementation of the virtual track in places where roads intersect, and AVs must navigate this crossing with relative precision. Additionally, road crossings in urban environments are usually in areas with taller buildings, making GNSS multipath propagation likely.

A key element is radio interference, which can be divided into two levels: intentional and unintentional. Intentional interference refers to situations in which disruption of the GNSS signal is caused deliberately—for example, through the use of jammers or spoofing devices—with the aim of intentionally degrading positioning accuracy or completely disabling satellite navigation. Such interference may be motivated by cyberattacks, privacy protection, military operations, or malicious misuse. This type of interference is unpredictable, as it does not arise from known physical phenomena (e.g., reflections, atmospheric effects), is not bound to a specific location or time, can be activated anywhere and at any time (often using portable equipment), and cannot be identified in advance through standard interference maps.

In contrast, unintentional interference occurs spontaneously as a by-product of other electronic systems, such as poorly shielded transmitters, radars, cellular base stations, microwave links, or vehicle electronic systems. This type of interference is typically localized, and its occurrence can be predicted and measured, since it is associated with specific sources of electromagnetic radiation and their harmonic frequencies that overlap with GNSS frequency bands. These emissions typically occur at higher harmonic frequencies of the nominal carrier wave. If some higher harmonic frequencies lie within the GNSS frequency bands, they can cause errors in pseudo-range measurements or completely prevent the GNSS receiver from functioning. This type of interference can usually be considered as an additional noise source for the GNSS receiver.

Another element is road construction work. In the road network (highways, primary, secondary, and tertiary roads), about 1200 construction activities occur annually [

11]. If we add interventions in buildings in the immediate vicinity of the road, autonomous vehicles must cope with a high number of changes in their planned route. This case is one of the few that have high efficiency and economic benefits, and the speed with which navigation adjustments can be made with extraordinary precision is unparalleled.

Experience from work zones shows that key factors contributing to congestion and accidents include poor merging behavior (zipper principle), speeding, short headways, and low driver courtesy. At the same time, mobile telematics systems have been proven to reduce delays and improve safety. This supports the deployment of virtual lanes as a complementary navigation element in such areas [

12].

The main problem associated with INS (Inertial Navigation System) is the accumulation of errors, which grows quadratically over time. This error arises mainly due to the integration of accelerometers and gyroscopes. The error in INS localization thus evolves over time and is usually modeled as follows:

where

a represents the sensor error and

t represents time.

In a real environment, the accumulation of errors from vehicle speed, errors due to the environment, and, last but not least, noise due to signal interference have a significant impact. In addition, the settings of the sensor itself, such as update rate, zero speed updates, etc., affect the data quality and error magnitude.

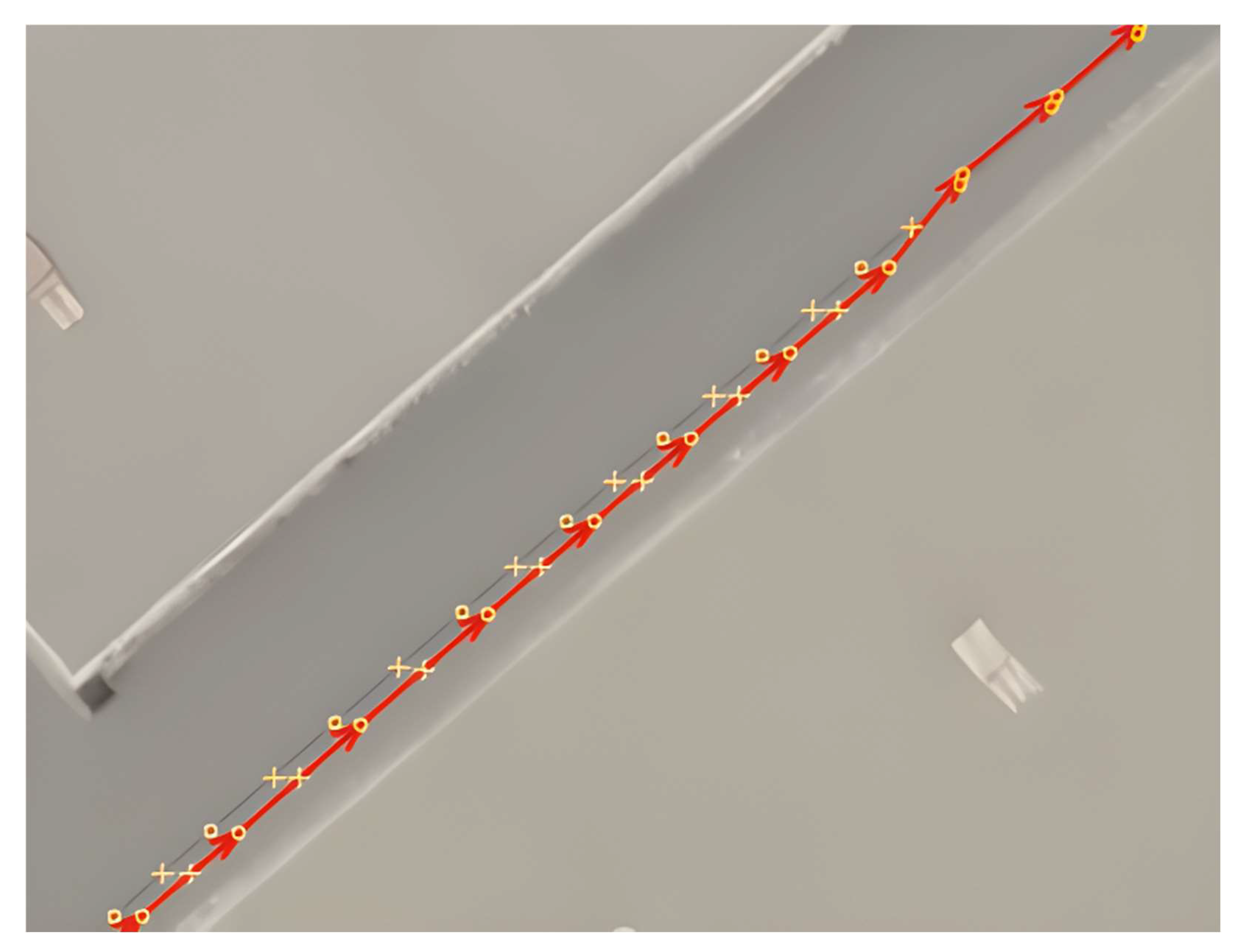

In places where the quality of satellite navigation is not up to the required level, it is necessary to provide another type of navigation apparatus. It is in these infrastructure locations that virtual tracks are becoming the dominant system for autonomous vehicle navigation. To make the use of virtual tracks highly efficient, we present a GNSS data verification method that can be used to identify locations where the virtual track is the dominant guidance system. Verification of localization accuracy consists of comparing the localized trajectory with a reference trajectory (

Figure 2). The comparison means calculating errors based on the difference between trajectories at a given time. The position error is computed as follows:

where the position error

xi is equal to the difference between the reference trajectory point and the position computed by the localization algorithm. From these errors, metrics such as minimum and maximum error, standard deviation, and percentiles of the representation of each error can be computed within the segment. Based on this data, the algorithm settings and configuration of individual sensors can then be optimized.

The reference trajectory is determined using Post-Processing Kinematic (PPK), a GNSS data processing technique that allows refining the position of the device using a combination of data from the satellite system and reference stations on the ground [

13,

14,

15]. The advantage of PPK over other GNSS data processing methods is that it allows for refining the position of a device even in situations where a permanent link to GNSS satellites is not available, for example, in areas with strong signal obscuration. The disadvantage is that PPK is not applicable in real time, and the subsequent data processing is more complex and time-consuming than Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) [

16].

5. Navigation Technology

The navigation system must provide accurate guidance of vehicles according to predefined routes and ensure efficient and safe operation in real time. For this purpose, an Inertial Navigation System (INS) is used to provide accurate information on the position, speed, and orientation of the vehicle, even in the event of a GNSS signal failure. It combines data from accelerometers and gyroscopes for precise navigation. Another navigation system is LIDAR, which is based on real-time mapping of the environment and ensures safety when detecting obstacles. It can also be used as a sensor to detect virtual tracks in the invisible radiation spectrum. It enables virtual track detection in low-light conditions, for example, at night. Of course, high-resolution cameras (ideally full HD 1920 × 1080 px resolution) are an integral part of the system, which can detect virtual tracks in the visible spectrum of radiation (optical detection principle), and can also be used to detect objects, traffic signs, and traffic lights.

The autonomous vehicle navigation system consists of several key modules (parts of the entire software architecture), which together provide route planning, trajectory generation, and subsequent vehicle control. This system consists of the following basic components:

Performs a high-level control and decision-making role (state machine) over the entire navigation system. Its main task is to start and stop the autonomous mode of the vehicle, to select route waypoints, or to ensure the correct behavior of the vehicle when stopped. It also works with the OpenStreetMap (OSM) and stores the state of the autonomous system, which includes modes such as ‘no mission’, ‘at stop’, ‘in motion’, or ‘error’. It also evaluates requests from the DBW (drive-by-wire system) and decides on the next course of action.

- (2)

PathRouting

It works with the output data from Mission Control and its main task is to determine the route to the destination. This module works similarly to the GPS navigation system-it calculates the sequence of map segments that lead to the destination.

- (3)

Trajectory Planner

It is responsible for accurately plotting the trajectory to be followed by the vehicle and includes planning speed limits. This planner has the ability to adjust the trajectory based on obstacles along the route and recalculate it if necessary. It contains two main subcomponents: the Behavioral Planner, which determines vehicle behavior (e.g., steering, following, stopping), and the Trajectory Updater, which calculates the final trajectory based on the defined behavior and other parameters.

Before creating the final trajectory, the module processes the map segments, which includes smoothing the trajectory and resampling it evenly. This preliminary trajectory is then used to generate the final trajectory, which contains the following information:

Planned profiles of speed, acceleration, and deceleration at each point of the trajectory;

Adjustments to the trajectory to avoid obstacles;

Connecting trajectory for a smooth transition to the base trajectory.

The final trajectory should then be based on the current position of the vehicle.

- (4)

Car Driver

Represents the low-level control module of the vehicle. Based on the trajectory obtained from the planner, it calculates the necessary steering (turning radius and target speed) to allow the vehicle to follow the planned trajectory accurately.

Each of these modules works together to form a comprehensive navigation system that enables the autonomous vehicle to reach the destination of the planned route.

5.1. Localization System

The localization system of an autonomous vehicle is crucial for ensuring the precise position of the vehicle in space. This system uses a combination of several technologies to achieve maximum accuracy even in challenging conditions where standard GNSS signals cannot provide reliable positioning [

18]. The localization system is built on two main pillars:

An Inertial Navigation System (INS) equipped with RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) technology provides high-accuracy positioning using a combination of GNSS signals and accelerometer and gyroscope measurements. The RTK-enabled INS can achieve accuracy on the order of centimeters, which is crucial for locating the autonomous vehicle in challenging conditions and for correcting any drift. RTK works with GNSS reference stations that provide correction data, allowing the elimination of errors caused by atmospheric conditions and other influences that would overload a standard GNSS signal.

- (2)

Virtual track localization

The virtual track is another possible technology used to enhance the positioning of autonomous vehicles, especially in areas with limited GNSS signals. This system utilizes lines or markers placed on the road, which serve as reference points and provide auxiliary data for determining the vehicle’s position. The virtual track thus helps the localization system keep the vehicle on the correct path and is very useful in tunnels or areas with poor GNSS coverage.

To achieve the most accurate localization, the resulting position of the vehicle is obtained by combining all the aforementioned sources using a particle filter. This advanced algorithm fuses data from the INS and the virtual track, improving reliability and accuracy. The particle filter creates a probabilistic model of the vehicle’s current position, which is continuously refined based on available data and estimates the most probable position. This ensures that the vehicle remains accurately localized even in dynamic conditions. The localization system, which combines all the mentioned components, provides the autonomous vehicle with a robust and reliable way to determine its position, which is crucial for safe and efficient operation in various conditions.

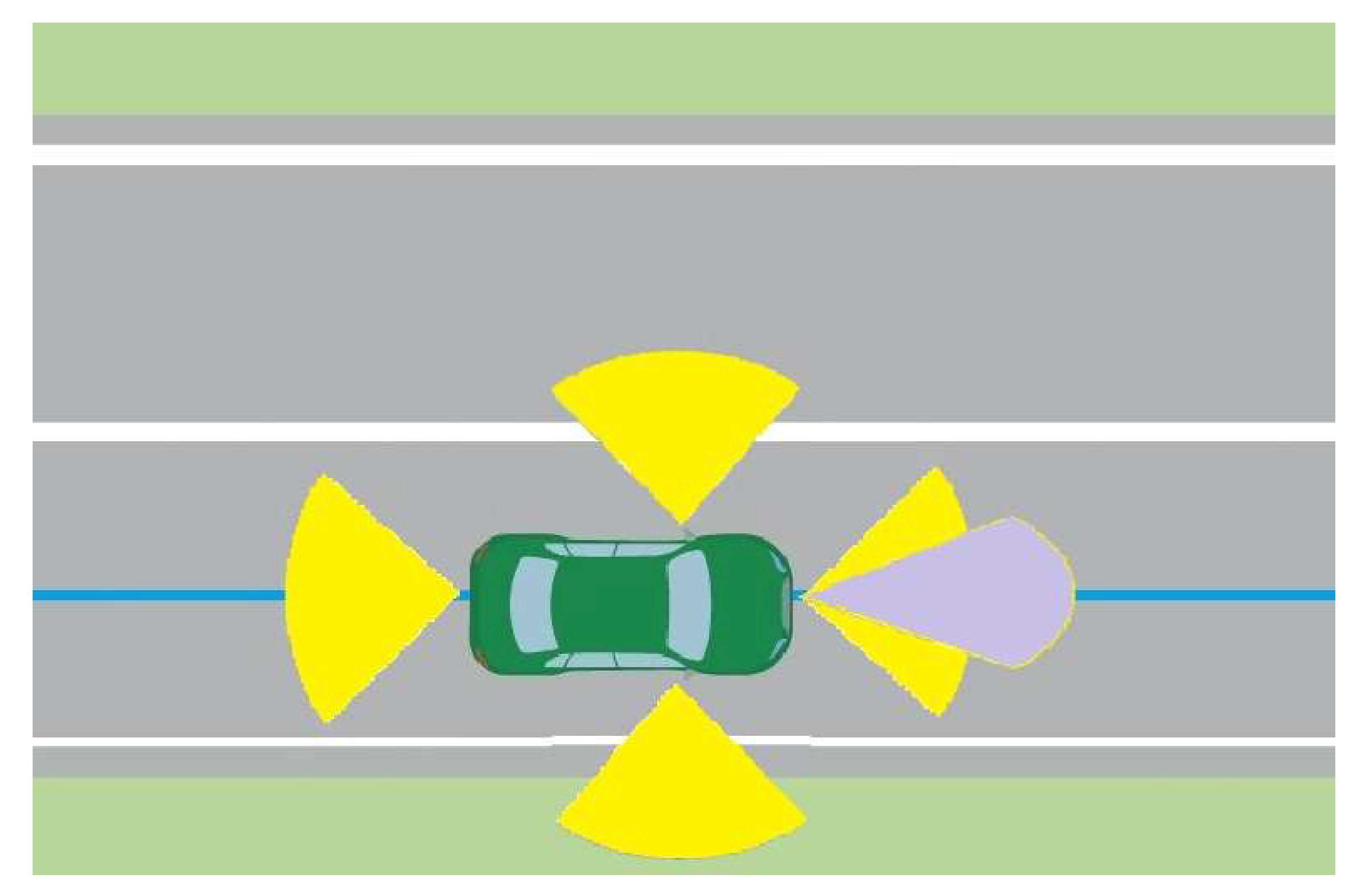

5.2. Integration of the Sensor Set with the Autonomous System

Sensors must be physically mounted on the vehicle with optimal visibility and maximum utilization of the field of view in mind. Besides optimal sensor placement, their calibration is essential. Static calibration of individual sensors is performed to define their positions and mutual orientations (extrinsic calibration), which includes synchronizing time stamps for each measurement. Intrinsic calibration of cameras is also important to compensate for lens distortion. After mounting and calibration, it is necessary to ensure that the sensors are correctly connected and synchronized with the central unit of the autonomous system, which controls and analyzes the data.

Most sensors are connected to the central control system via a CAN bus or Ethernet for fast and reliable data transmission. Synchronization using a precise time server or synchronization protocol (e.g., PTP–Precision Time Protocol) is necessary to ensure that data arrives with consistent time stamps.

After integration, it is necessary to verify that all sensors and the localization system work reliably and that the autonomous system can correctly use the localization data to control the vehicle. Initial verification is conducted in simulated environments where various operating conditions and obstacles can be modeled. This is followed by verification in real conditions. Based on test results, fusion algorithm parameters, such as filter settings (particle filter), are adjusted to achieve optimal accuracy and stability.

In the final phase of integration, a monitoring system is introduced to track sensors and their functionality during operation, allowing for rapid detection and correction of potential faults. Algorithms need to be adapted to function reliably under varying light conditions, rain, fog, or the presence of obstacles on the road. Implementing a system that continuously monitors sensors and detects anomalies ensures long-term reliability and minimizes downtime during operation.

Integrating the sensor set into the vehicle’s autonomous system is a demanding process that requires detailed calibration, synchronization, and testing of all components to ensure reliable and accurate vehicle performance in real-world conditions.

8. Development and Validation of Coating Materials for Virtual Tracks

During the practical tests, we focused on the development of coating materials (CMs) intended to serve as a virtual rail. For the preparation of samples for testing, it was essential to use materials suitable for application on various substrates. Depending on the surface structure, the coating material may exhibit different properties. For road-marking coatings, thermoplastic, methyl methacrylate (MMA), acrylate, epoxy systems, or pre-formed films are typically used. Their properties differ in terms of cost, performance, durability, and application rate. For our purposes, solvent-borne acrylate CM and methyl methacrylate CM were selected. Solvent-borne acrylate CMs are used for marking asphalt and concrete pavements. They are fast-drying, one-component (1K), and durable. Single-component acrylate paints are the most commonly used road-marking materials in the Czech Republic, thanks to their cost efficiency and the fact that no special application equipment is required. Their drying mechanism is based on physical drying—evaporation of solvents.

Two coating materials were selected for the experiment: DEGALAN LP 64/12 and LG BA140 MMA (

Table 1).

DEGALAN LP 64/12 is a methacrylate-based polymer binder for traffic markings. It is weather-resistant, lightfast, and chemically stable. It is soluble in esters, ketones, glycol ethers, and aromatics. It is compatible with most PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) copolymers, nitrocellulose, chlorinated rubber, plasticizers, and is partially miscible with alkyd and epoxy-ester resins. Appropriate additives such as fillers and pigments, together with the binder, form an air-drying CM suitable for urban traffic markings. The coating may be applied using fully automatic one-component spraying machines or with a roller.

LG MMA BA140 is a thermoplastic acrylate binder with balanced physical properties such as hardness and flexibility, offering excellent adhesion to various substrates. It combines methyl methacrylate and ethyl acrylate in its structure. It can be used with various general-purpose solvents. The binder exhibits excellent weather resistance and good flexibility and is soluble in esters, ketones, and aromatics.

During the preparation of the coating materials, various additives were used to achieve optimal performance, including solvent, binder, filler, wetting and dispersing agents, thixotropic agent, rheological additive, plasticizer, and pigment, depending on the specific sample requirements. The pigments used included different variants of Iriotec (conductive, IR-absorbing pigment), Fepren (black, dark brown, orange, red pigments), Printex (conductive carbon black), and titanium dioxide (white pigment); see

Table 2. All formulated coatings were tested for tack-free time according to ČSN EN ISO 9117-5 [

32], hardness according to ČSN EN ISO 1522 [

33], bending resistance according to ČSN EN ISO 1519 [

34], and adhesion according to ČSN EN ISO 2409 [

35].

The initial phase involved testing the preparation of the coating material (CM) based on DEGALAN LP 64/12. The reference formulation provided by the manufacturer was modified according to the availability of raw materials and was further adjusted step-by-step depending on the resulting consistency. Pigments were also added to the base CM, partially replacing the titanium dioxide present in the original manufacturer’s formulation. For each pigment, a mixture was prepared to achieve a pigment volume concentration similar to that of the base mixture (DL-0). PVC represents the ratio of the total volume of pigments, fillers, and other non-film-forming solid particles in the product to the total volume of non-volatile components, expressed as a percentage. Various pigment types were tested (

Table 2). All coating materials were applied wet at a thickness of 300 μm on glass substrates.

The electrical resistance of the coatings on glass was measured using a handheld VOLTCRAFT R-200 CAT III 600V multimeter and two electrodes spaced 1 cm apart. Only the CM containing Printex L6DL carbon black exhibited a slight response, with measured values in the tens of kΩ. Based on these preliminary resistance measurements, pigment concentrations were increased. In some cases, the pigments completely replaced both the original titanium dioxide and the calcium carbonate filler. The concentrations of functional pigments were gradually increased up to 30 wt.% for both Fepren pigments and Iriotec pigments. For carbon black, the maximum concentration was 3 wt.%.

For subsequent mixtures, the pigments Iriotec 7320, Fepren HM472A, Fepren TP 200, Iriotec 7320, and Iriotec 7325 were excluded. The reasons for eliminating these samples included the appearance of the resulting CM, its consistency, and the fact that at the given concentrations, the mixtures became unsuitable for proper blending. During the development process, dispersing agents were also modified to improve the pigment dispersion within the CM. The original set of 10 + 1 samples was gradually reduced to six. Electrical resistance measurements were carried out on these selected samples as well; see

Table 3.

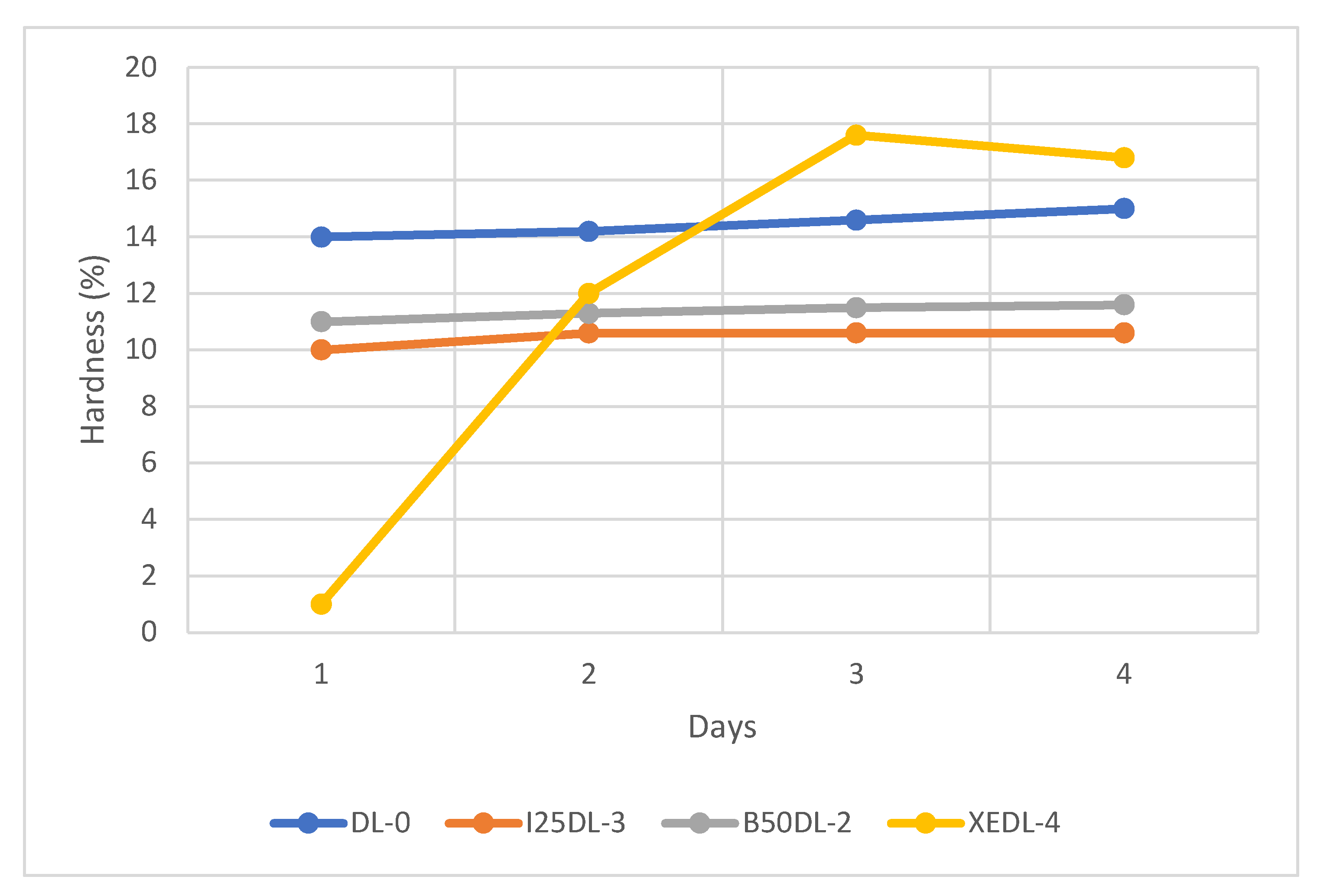

It is therefore evident that even after adjusting the pigment concentrations, the electrical responses remained relatively low or completely absent. Based on the measured electrical response, additional samples were eliminated, and the final accelerated mechanical-property tests were carried out only on samples B50DL, XEDL, and I25DL, which exhibited a measurable response. The prepared coating materials were subjected to hardness testing (

Figure 4), drying-time assessment, adhesion testing (

Figure 5), and bending resistance. Mechanical properties were evaluated after 1, 3, 7, and 14 days following the application of the coatings onto glass or metal sheets. For the intended use of the coatings as a virtual track, hardness and adhesion are the most important parameters in terms of road-surface performance.

The base coating material DL-0 (without added functional pigments for comparison) exhibited slightly higher hardness on the glass substrate than the coatings containing Fepren B650 (B50DL) and Iriotec 7325 (I25DL). The hardness of these coatings did not change over time. A noticeable increase in hardness was observed in the coating containing carbon black (XEDL). In this sample, hardness increased over time, and after seven days, the achieved hardness values exceeded those of the base coating without functional pigments.

The adhesion of the coatings on a steel substrate deteriorated over time. The poorest adhesion was found in the coating containing carbon black (XEDL). The base coating (DL-0) showed poor adhesion to the steel substrate after 14 days, which may be attributed to the fact that these coating materials are not primarily intended for this type of substrate. Unfortunately, adhesion tests on actual pavement materials could not be performed using this method. The same tests were conducted for the LG sample set, and the results were similar, again due to an unsuitable choice of substrate.

The second set of samples tested was based on LG BA140 MMA. The reference formulation provided by the manufacturer was modified according to the available raw materials and was further adjusted stepwise depending on the consistency. Pigments were again added to the base coating material, partially replacing the titanium dioxide present in the original formulation. For each pigment, a mixture was prepared to achieve a pigment volume concentration comparable to that of the base mixture (LG-0). Various pigment types were tested (

Table 2). All coating materials were applied wet at a thickness of 300 μm on glass substrates.

The electrical resistance of the coatings on the glass substrate was measured using a handheld VOLTCRAFT R-200 CAT III 600V multimeter with two electrodes spaced 1 cm apart. None of the coatings showed any detectable response. Based on these preliminary resistance measurements, pigment concentrations were increased. In some cases, the pigments completely replaced the original titanium dioxide and the calcium carbonate filler. The concentrations of functional pigments were gradually increased up to 30 wt.% for both the Fepren and Iriotec pigments. The maximum concentration for carbon black was 3 wt.%.

For further formulations, the pigments Iriotec 7320, Fepren B5330, Fepren HM472A, Fepren OG75, Fepren TP 200, Printex L6, and Iriotec 9230 were eliminated. These samples were excluded due to the appearance of the resulting coating, its consistency, and the fact that, at the given concentrations, the mixtures became unsuitable for proper blending. The original 10 + 1 samples were gradually reduced to three. Electrical resistance was measured for these remaining samples; see

Table 4.

These samples were the only ones to exhibit any measurable electrical response. Therefore, the accelerated mechanical-property tests were carried out only on samples B50LG, I25LG, and XELG. The prepared coatings were subjected to hardness testing (

Figure 6), drying-time assessment, adhesion testing, and bending testing. Mechanical properties were evaluated after 1, 3, 7, and 14 days following application to glass or steel panels. For the intended use of the coating material as a virtual track, the most important parameters in terms of road-surface performance are hardness and adhesion.

The base coating material (LG-0) gradually increased in hardness over time. The highest hardness values were again observed in the mixture containing carbon black (XELG). Overall, all mixtures using this binder exhibited higher hardness values than the previous formulations based on Degalan (see

Figure 4).

Regarding adhesion of the coatings to the steel substrate, a deterioration over time was again observed. The poorest adhesion was found in the coating containing carbon black (XELG) and in the coating containing Fepren B650 (B50LG). Unfortunately, adhesion tests on actual pavement materials could not be performed using this method. Thus, the substrate used for this adhesion test was again not suitable.

In the final phase of laboratory testing, the selected samples from both sets were subjected to accelerated weathering tests using QUV chambers. The determination of coating resistance under UV lamps was carried out in accordance with ČSN EN ISO 16474-3 [

36]. This involves the exposure of coatings to fluorescent UV light, heat, and water in equipment designed to reproduce aging effects. The samples were exposed under controlled conditions (temperature, humidity, and/or presence of water). The test conditions for the selected coating materials were as follows:

Irradiation phase: 60 °C, 4 h;

Condensation phase: 50 °C, 4 h.

For the DL series (

Figure 7), the samples exhibited rusting after exposure (with the exception of the baseline control sample DL-0). The only sample that did not show rust formation was the carbon-black-containing sample (XEDL). For this sample, the adhesion test was repeated, as the chamber exposure conditions had a positive effect on the adhesion to the substrate. It can therefore be assumed that this behavior may also be applicable to pavement materials.

For the LG series (

Figure 8), the samples containing pigment I25LG (Iriotec 7325) showed rusting after exposure, similar to the previous sample set. However, the remaining samples—B50LG and XELG—did not exhibit any visible signs of degradation. Regarding adhesion after exposure, an improvement was observed in sample B50LG (Fepren B650). For the other samples, adhesion values remained unchanged compared to the pre-exposure measurements.

8.1. Principle of Verifying Track Visibility in Field Conditions

Based on the laboratory tests, samples that best met the requirements for virtual tracks were selected. These samples were subsequently refined and applied within the BVV (Brno Exhibition Centre) premises. The BVV area was chosen because it provides a location where autonomous navigation using a virtual track can be tested safely, while the varying quality of ambient signals is essential for verifying navigation reliability under different environmental conditions.

INS sensor data processed using PPK (Post-Processing Kinematics) were selected as the source of the reference trajectory. This method enables trajectory refinement to the millimeter level, which is significantly more precise than required for accurate autonomous vehicle navigation. The resulting trajectory can therefore be used as ground truth. In this context, virtual track detection is used as an input for improving the vehicle’s positional accuracy.

The BVV complex is an exhibition area with limited traffic, which is advantageous for safe vehicle testing. Most locations on the premises feature horizontal and vertical road markings, providing conditions similar to real road environments. Since the development of the virtual-track coating revealed insufficient magnetic properties, temporary magnetic tapes were applied to the pavement for testing purposes. To further enhance navigation using optical sensing (LiDAR, camera), the existing centerline road marking was utilized.

8.2. Shuttle Bus and Core Equipment

For testing purposes, an Esagono Grifo Shuttle (

Figure 9) was used—a compact, fully electric minibus that serves as a technical platform for autonomous-driving research. The vehicle is based on the Geco Shuttle model and accommodates up to seven passengers. Its N1 homologation ensures compliance with European safety and operational standards for both passenger and cargo transport.

From the perspective of autonomous operation, the vehicle is equipped with a Drive-by-Wire system, enabling electronic control of acceleration, braking, and steering via the CAN bus (Controller Area Network bus). This includes not only actuation commands but also feedback from the vehicle—information about current speed and steering angle is essential for real-time trajectory control. The vehicle architecture also allows switching between manual and autonomous modes, which is important both for safety and for experimental validation.

The autonomous driving function is enabled by an integrated sensor system that combines multiple types of input data for precise localization, environmental perception, and detection of the virtual track. The system includes a Sick MLS magnetic sensor, Livox MID-70 LiDARs, and Lucid Vision Labs TRI051S cameras, whose placement and roles are carefully designed with respect to operational scenarios and redundancy. The setup also incorporates a Nuvo VTC9100 computing unit.

The magnetic sensor is mounted in the lower part of the vehicle, close to the road surface, because it can detect the specially applied road coating—the virtual track—only within a range of a few centimeters. It serves as a supporting or backup localization element, particularly in environments where GNSS signal loss occurs. This ensures that the virtual track remains reliably detectable, allowing the vehicle to navigate autonomously even without satellite navigation.

Three LiDAR units are installed on the roof of the vehicle, providing a 3D scan of the surroundings and supporting both map generation and map updates. They also contribute to localization relative to the static environment—such as buildings, trees, or other permanent landmarks—and ensure spatial orientation. Furthermore, they play a key role in obstacle detection and monitoring of traffic conditions.

Cameras positioned around the perimeter of the vehicle provide visual information about the surroundings, particularly about dynamic objects such as pedestrians, cyclists, or other vehicles. They also enable visual detection of the virtual track when it is marked using colored elements. In addition, the cameras form part of the remote-supervision system. In the event of an autonomy failure, the vehicle can be safely teleoperated using the video feed and teleoperation interface. This mode serves as a fallback solution for scenarios in which the autonomous system is unable to resolve the situation.

The entire sensor suite is designed to enable the combination of global and local localization, thereby increasing the robustness of navigation in real-world operation. Through data fusion from all sensors, the shuttle is capable of autonomous operation even in areas with limited or completely unavailable GNSS signals, which is essential for deployment in urban environments.

An algorithm that determines the vehicle’s position using sensor data is called localization. In the default configuration, localization operates only with data from the INS. Additional sensors can be gradually integrated to utilize data from multiple sources. This process is referred to as sensor fusion, which ensures greater robustness of the solution. In areas with poor signal reception, for example, odometer data from the vehicle can be used.

The core of localization is the particle filter. It is a probabilistic model used to estimate the vehicle’s position. The simplified general principle is as follows:

Generate a set of particles, each particle having a position [x,y,z].

Repeat–calculate the probability that the particle’s position corresponds to the actual vehicle position, and resample the particle set according to this probability.

In this way, the estimated position gradually converges to the most probable value. Within our software, the position estimation is divided into two steps: predict and update.

First step—predict: a large number of particles are generated, representing estimates of the vehicle’s position based on accelerometer and gyroscope data.

Second step—update: for each particle, its weight is calculated according to information from the GNSS receiver. The vehicle’s position is then determined as the mean of all particle positions.

Assuming that the virtual track has magnetic properties, its position could be detected using a Sick MLS magnetic sensor. However, the tested paint samples did not generate a sufficiently strong magnetic field to be detected by this sensor. Therefore, a camera facing forward in the vehicle’s direction of travel was chosen for virtual track detection. The image is semantically segmented into several regions using a neural network. Only the part of the image corresponding to the line can be extracted, and the line center can be located.

The camera provides only 2D information about the line’s position; for localization, the line’s position in 3D must be determined. For this purpose, a Lidar, calibrated relative to the camera, can be used. The line center can be found in the aggregated 3D Lidar scan. The difference between the measured line position and the actual position is used as additional input for updating the particle filter weights, which should ensure greater robustness and accuracy of localization.

8.3. Pilot Testing of Virtual Tracks

Before initiating pilot operation, selected samples were laboratory-tested using the Livox MID70 Lidar, (Livox Technology Company Limited., Shenzhen, China) which later became part of the test setup. The Lidar is equipped with a laser with a wavelength of 905 nm. Its detection range at 100 klx is 90 m at 10% reflectivity, 130 m at 20% reflectivity, and 260 m at 80% reflectivity of the scanned object. The field of view (FOV) is circular with an angle of 70.4°. Range accuracy (1σ) is ≤2 cm at 20 m and ≤3 cm at 0.2–1 m. Angular accuracy is less than 0.1°. Beam divergence is 0.28° (vertical) × 0.03° (horizontal). Scanning speed reaches 100,000 points/s for the first or strongest return, and 200,000 points/s for dual returns.

The paint samples were labeled as VERLG-0, VERLG-2, OGLG-2, 198LG-4, 125LG-2, and KRLG-0. All samples were applied on a black-and-white target, providing a uniform reference standard for visual assessment and comparison of paint properties. During measurements, the strongest return mode was used. Samples were placed on a matte black background and scanned from a distance of 1.5 m for 10 s, with a total of three measurements per sample. After processing the RAW data, three points on the light background and three points on the dark background were selected in each recording and for each sample to account for background influence on the paint and to prevent reading errors (

Table 5). Among the tested samples, 198LG-4 and KRLG-0 exhibited the highest reflectivity values, regardless of the background color on which the paint was applied.

Subsequently, tests were conducted under real-world conditions. It was essential to apply the paint in a way that allowed modification of the virtual track during testing, including the simulation of intersections between two virtual tracks. Linoleum was selected as the base material for paint application due to its mechanical, chemical, and weight properties. Linoleum strips of 15 cm width and 400 cm length were prepared, and the paint was applied to them. The total testing length was 44 m for each paint type.

To ensure reliable autonomous vehicle operation, it is critical to test its navigation system under various weather conditions. The sensor systems on which the vehicle relies can be affected by environmental factors. Therefore, pilot testing was conducted on an autonomous vehicle equipped with sensors and a navigation system adapted for virtual track detection. Ideally, the virtual track should be detectable at all times by all sensors, or at least one of the sensors (camera, Lidar, magnetic field sensor). The objective was to determine whether the navigation system remained accurate and reliable under adverse conditions, such as weak GNSS signals, poor visibility, or weather-related influences.

8.4. Test Scenarios

For testing purposes, various scenarios were designed and implemented to thoroughly evaluate the system’s ability to detect and track the virtual track. In accordance with legislative requirements and real-world operational conditions, two main configurations were examined: placement of the virtual track in the center of the roadway and along the vehicle’s longitudinal axis. Both configurations were tested in several specific scenarios to ensure that the system performs effectively under different conditions and configurations. The following scenarios were defined:

Solid line along the vehicle axis: this scenario simulated the situation in which the vehicle follows the ideal trajectory directly along the virtual track.

Solid line to the left of the vehicle (simulation of the center line): this scenario represented driving near the road’s center line, which is common in urban traffic.

Dashed line to the left of the vehicle: testing the system’s ability to recognize a dashed line, simulating situations where the line is partially visible or incomplete.

Solid line along the vehicle axis: environment with a poor GNSS signal.

To assess positioning accuracy, it was critical to compare the reference trajectory with the trajectory recorded in real time. During testing, all trajectory points were analyzed to determine the mean deviation. In addition to the mean deviation, the variance and maximum deviation from the reference trajectory were evaluated, providing important information on the system’s performance limits under different conditions. These evaluations allowed for an analysis of the autonomous vehicle’s ability to navigate accurately under varying conditions, which is crucial for its future practical deployment in both urban and non-urban environments.

As shown in

Figure 10, the largest deviation occurred during rainy conditions. Based on line type, the worst orientation was observed with the dashed line under any weather condition. This is a logical outcome, since the detected element is intermittent, making it more challenging for the system to detect it optimally, which increases deviation. Very favorable results were observed during nighttime testing, where the reflectivity of the element significantly contributed to its detection. Regarding the solid line along the vehicle axis and the solid line to the left of the vehicle, the results were very similar.

During testing, it was verified that the virtual track can be detected in real-world conditions using different sensors and that the detection information can be utilized for localization in a real environment (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). Data were recorded using an autonomous bus while driving in the vicinity of the virtual track.

Detection of the virtual track from the camera image was performed using image segmentation with a neural network. Semantic segmentation divides the image into several classes, including road lines, pavement, vehicles, sidewalks, and others. From the image, only the region classified as the track is selected. The coordinates of the line center can be determined by analyzing this region using computer vision techniques. This can be carried out by calculating the region’s centroid or by applying an edge detector followed by a Hough transform.

The colored bands in the LiDAR image represent different values of the measured variable. In this case, it is the intensity of the laser beam reflection, which indicates the amount of light reflected from the object. In

Figure 12, the virtual track (blue band) is clearly visible. Therefore, the colored bands are not arbitrary; they serve to visualize numerical values in the LiDAR scanning data, enabling a rapid distinction between varying object heights or reflection intensities.

During the tests, sections without a track, with a dashed and solid straight track, intersections of two tracks, a curve, a curve with an interruption, and a track split were monitored. Each scenario was recorded repeatedly. Magnetic detection was unfortunately not possible due to a weak response, which represents a challenge for future work. However, all tracks were successfully detected using the camera and Lidar. The following images show a selection of notable scenarios (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

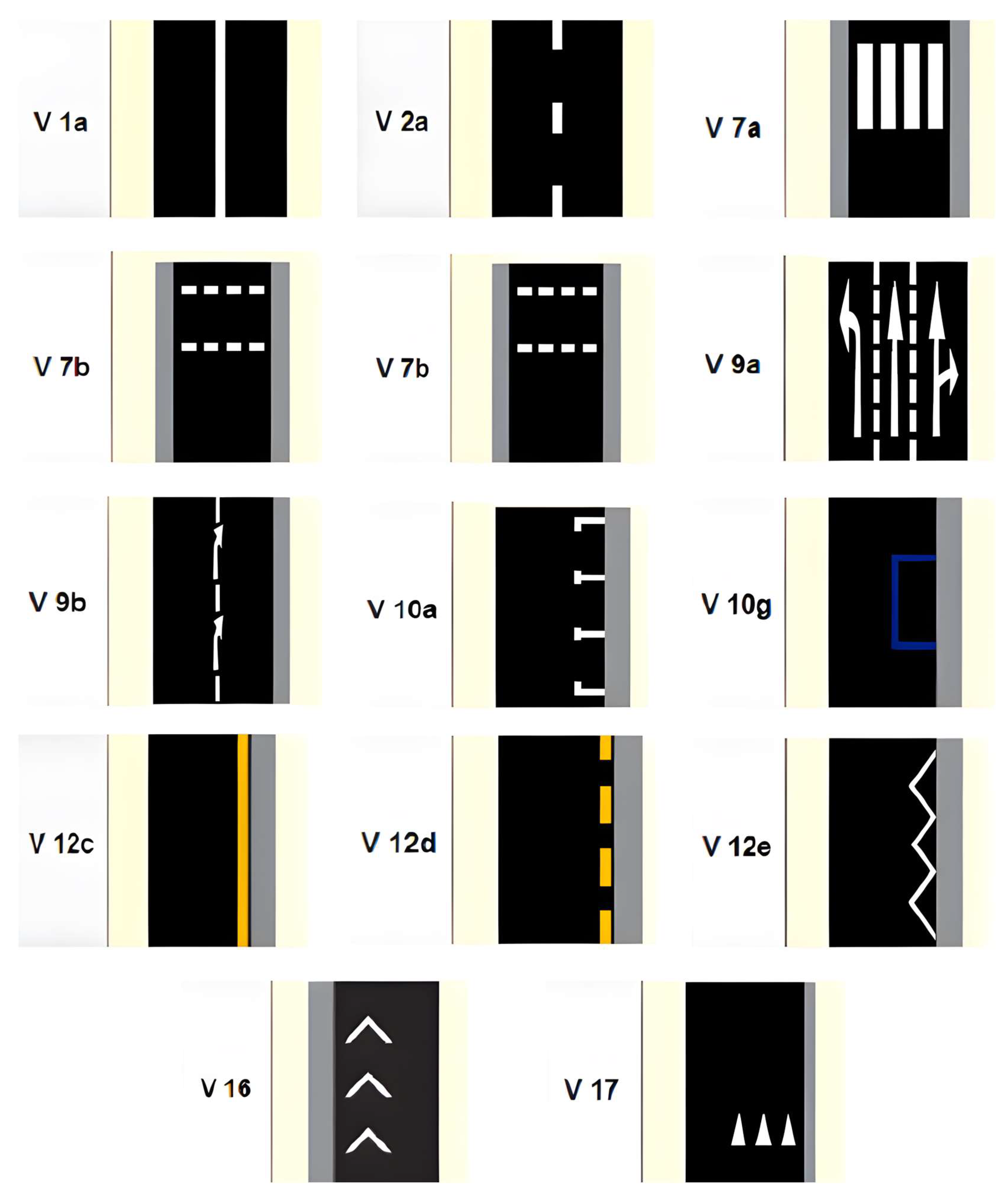

9. Optimization of Marker Parameters and Their Traffic Psychological Impact

To enhance the navigation of autonomous vehicles using virtual track markers, the correct dimensions, shape, and color of these objects are crucial. They must be clearly recognizable by both cameras and Lidar; otherwise, their existence loses its purpose.

In addition to the technical parameters of virtual tracks, it is also necessary to consider the characteristics of traffic psychological parameters. It is essential to ensure that these virtual tracks are distinguishable from horizontal traffic signs by other drivers. It is not just about preventing drivers from confusing virtual tracks with horizontal traffic signs, but also about ensuring that they do not distract drivers while driving. This is a psychological aspect.

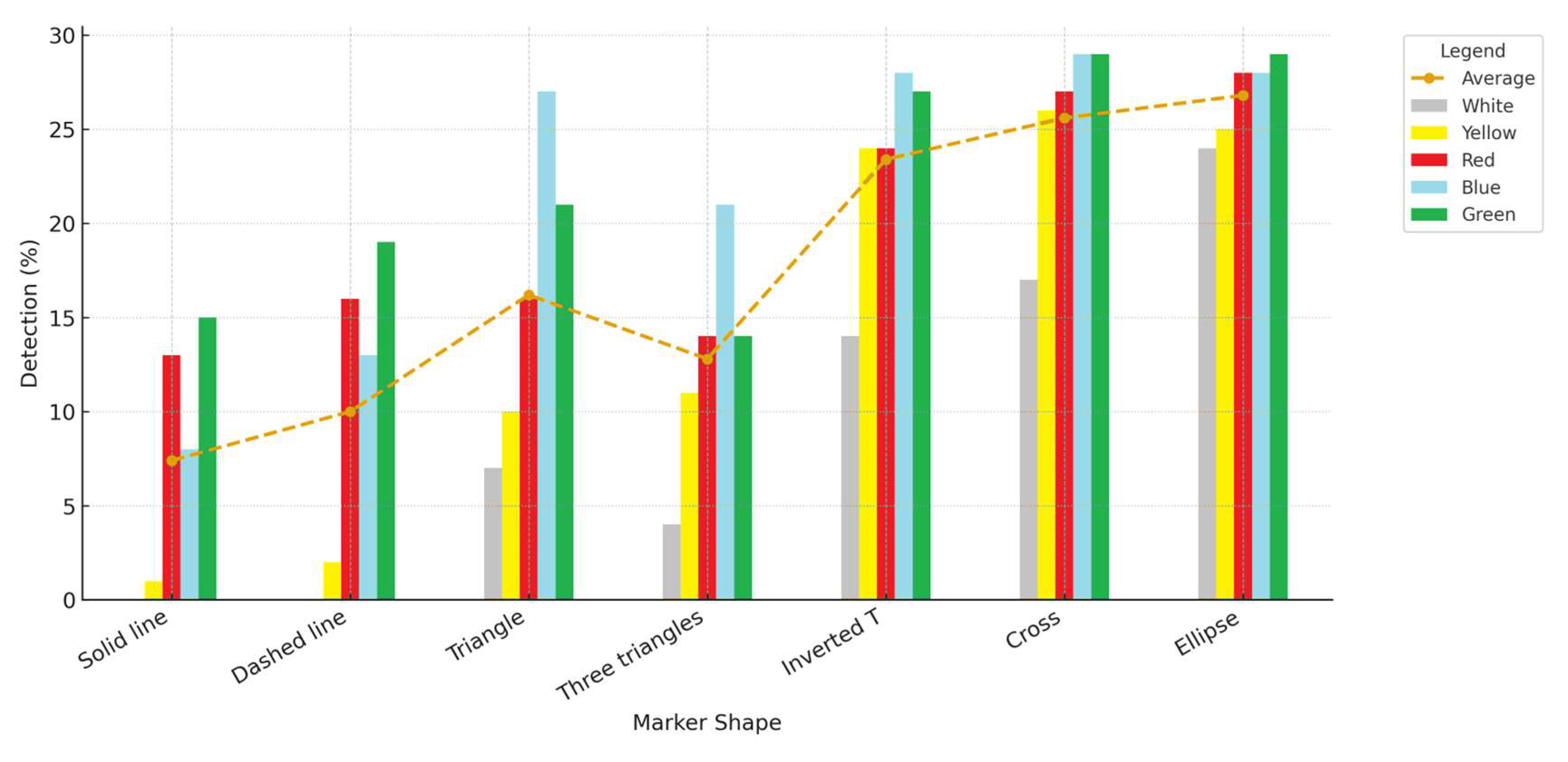

For this reason, a psychological experiment was conducted to examine drivers’ ability to distinguish between variants of virtual tracks and horizontal traffic signs. In this experiment, participants were exposed to images of the road. These individuals were tasked with determining whether the image contained only horizontal traffic signs or also objects that were not horizontal traffic signs. The full factorial design tested 7 shapes (solid line, dashed line, triangle, three triangles, inverted T, cross, ellipse) and 5 colors (white, yellow, red, blue, green), see

Figure 15. Thus, 35 items were administered to the test subjects. The first four shapes evoked horizontal traffic signs based on the color combination, while the other three shapes proved to be suitable markings for the virtual track.

The experiment was administered via a web form and randomly selected volunteers participated (

Table 6). Most respondents are experienced middle-aged drivers, which increases the validity of the results for the general driving population.

Table 7 shows the results of object detections that are not horizontal traffic signs. Values are given in percentages.

As illustrated in

Figure 16 and

Table 7, the most effectively detected colors include blue (22%), followed by green (22%) and red (19.7%). At first glance, it is evident that the blue triangle, achieving 27%, was well recognized; however, when assessed from a global perspective, this shape ranks only fourth among the detected objects, with a detection rate of 16.2%. Therefore, it is unsuitable as a universal shape. In contrast, the inverted T-shape (3rd place, 23.4%), the cross (2nd place, 25.6%), and the ellipse (1st place, 26.8%) demonstrate, even at first observation, that their representational consistency is sufficient across all color variations.

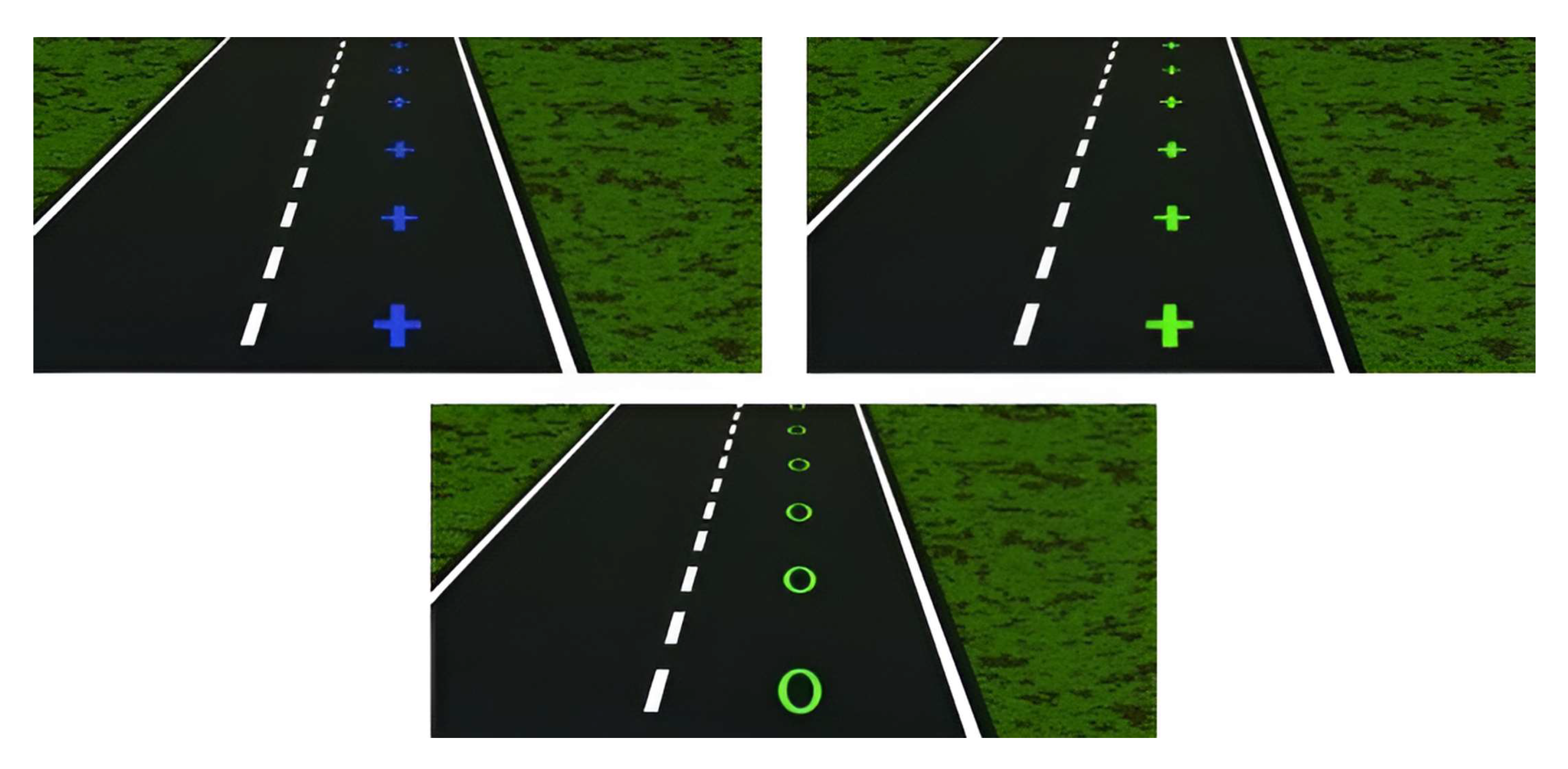

From the results, it can be concluded that the most advantageous shapes for virtual track markers are the cross and ellipse in combination with green color and the cross in combination with blue color (

Figure 17). Participants were always able to distinguish these objects from horizontal traffic signs. The poorest results were observed for the solid and dashed lines, regardless of color. According to the participants, these lines were easily confusable with standard horizontal traffic markings.

If we focus only on the color scheme of the markers, the most suitable are blue and green. If the virtual tracks had to consist of multiple markers close to each other, green would be much more suitable. Markers close to each other could resemble a dashed dividing line, but thanks to the color differentiation, their detection will be unambiguous.