1. Introduction

Urban infrastructure improvements, commercial development, and data center installation have been investigated in the literature [

1]. Furthermore, smart tourism, smart driving, and digitalization have aided the growth of the digital industrial economy [

2]. The IoT contributes to the development of smart cities by collecting data from different areas that contribute to improving people’s lives [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In the IoT, Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) nodes serve as the underlying technical backbone [

7].

IoT devices and sensors collect various data from different events and conditions, including temporal and geographical data. These tools are becoming smarter and are quickly able to communicate and perform complex tasks [

8]. The IoT continuously collects data through diffuse devices worldwide [

9] and contributes to different fields, such as healthcare, disaster management, and learning [

10]. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve healthcare is a major challenge due to advances and new research in medicine [

11]. Consequently, the software and infrastructure of healthcare that are supported by IoT must be developable to accommodate the latest updates in the field [

12]. Data analysis and decision-making based on IoT are important issues in the healthcare system, in addition to monitoring vital signs to predict the patient’s future state [

13]. Indeed, patient lives could be at risk, especially people who live alone, so monitoring data and vital signs is very important [

14,

15,

16]. However, the development of healthcare applications and software is a major challenge for developers due to the important, sensitive, and varied information related to patients, diseases, and treatment. However, medical applications and software based on IoT must be extremely accurate to analyze data and provide treatment, with legal approval from medical expert committees [

17,

18].

Professional, relevant information helps in monitoring serious cases and long-lasting diseases. Still, analyzing this information produces open questions like the parameters to be measured, the frequency of measuring, and the responsibility of new medical devices to monitor a patient’s health [

19]. Machine learning (ML) approaches are considered more efficient predictive models that use signs or other relevant patient data [

20]. Early detection is essential to preventing declines in health; furthermore, early prediction optimizes patient healthcare and reduces the cost of implementing related systems [

21].

The contributions of this study are as follows:

To create a new model called PLPF-MAS. This model consists of a multi-agent system that distributes tasks to independent agents (LR, AE, HMM, a coordinator, and a supervisor), making the model robust and expandable.

To improve the reliability of the model using two criteria (Prisk, ) to make decisions, provide warnings, and make recommendations.

To reduce data noise using an AE agent that compresses data by extracting important features to ensure the best training for the HMM agent.

To monitor and manage the model using a supervisory agent to retrain it depending on the risk state.

2. Related Work

An ML approach with a Kalman filter was employed to recognize movements related to various signals. This work demonstrated the efficiency of ML techniques, which are far better than the classical signal processing methods used in smart application analysis [

22]. Heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration were analyzed using a switching linear dynamic model whose function is identical to the Gaussian Learning Model (GLM). This model produced an accuracy of 74%, whereas the accuracy of GLM was 35.3% [

23]. Several investigations have been conducted to determine applications for ML techniques, showing that when mobile health data are used in smart applications, health conditions improve [

24].

One study investigated a plausible analytical transformation related to digital health data. The objective was to use digital health data drawn from wearable sensor-based smartphone devices [

25]. Structured and unstructured health information was analyzed using machine learning, artificial intelligence, and natural language processing methods to detect the level of risk among patients [

26]. In another study, the authors developed a cognitive dynamic system for a smart e-health system to automatically screen defective or abnormal datasets [

27]. A defective dataset may have poor labeling and/or insufficient training patterns. To mitigate the adverse effect of such a defective dataset, a decision-making system inspired by human decision-making processes used in cases of conflicts-of-opinion (CoOs) was developed [

28].

Our hybrid system uses ML social Internet of Things (SIoT) to address the problem of distributing medical services efficiently and overcoming the challenges of traditional models. It does so by favoring the social relationships between the objectives so that patients can access services quickly [

29]. The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) plays a role in the development of the healthcare system in smart cities. Its main function is to provide continuous monitoring and check the patient’s health state, which improves the quality of the healthcare system [

30]. We present a proof-of-concept implementation of this framework to automatically identify people experiencing arrhythmia using single-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) traces. The proposed CDS algorithm performs well with diagnosis errors and can be incorporated into the autonomic computing layer of smart-e-health–home platforms to achieve a pre-defined degree of screening accuracy in the presence of defective datasets [

31]. An IoT-based non-invasive automated patient discomfort-monitoring detection system is presented and implemented, using a deep learning-based algorithm. The system is based on an IP camera; the patient’s body movement and posture are detected without wearable devices. The Mask-RCNN method extracts different key points from the patient’s body. These key points are then associated with six major body organs using data mining association rules [

32].

This study was conducted using ECG and sleep audio signals. The ECG data included RMSSD, SDNN, and pNN50, and audio analysis produced parameters such as spectral moments, components, and MFCCs. Then, these parameters were used as inputs in a radio-frequency classifier, which was previously trained to recognize different types of breathing events (normal, snoring, gasping, and wheezing) [

33]. An autoencoder model (AE) reduces the dimensions of the healthcare dataset and then reconstructs this compressed data. This improves the classification of a Multilayer Neural Network [

34]. LSTM improves the accuracy of risk assessment for patient health states by analyzing the EHR dataset to determine the risk state in order to monitor the critical condition. The LSTM model results are superior to traditional models in risk assessment, leading to enhanced decision-making in healthcare [

35].

A hidden Markov model is used to predict the onset and progression of (SARS-CoV-2) infection using heart rate variability (HRV) data from smart wearable devices. The HMM is trained on a dataset prepared by the Welltory Lab, which includes participants’ self-reported (SARS-CoV-2) symptoms and HRV measurements. The data used depends on the hidden and observed states [

36].

The HMM model is a probabilistic model based on highly correlated HR data used to predict BP. Consequently, these vital signs do not require continuous measurement to be monitored, saving time and energy. The dynamic thresholds used in this system are calculated using the 3-sigma method, depending on interruptions in the previous data, to determine if vital signs are normal or within risk ranges. The HMM model is trained using data from patients with elevated heart rates and blood pressure, classifying sequences into “critical” (tachycardia and hypertension) and “normal” states based on the probability of the observed sequence in each model. Only critical data is stored during interruptions, reducing memory usage and transmission needs upon reconnection. The Viterbi algorithm estimates the most probable hidden states (blood pressure) from the observed heart rate data to develop a reliable and energy-efficient method of continuously monitoring vital signs in elderly patients using an HMM. This addresses the challenges of data loss and high energy consumption [

37]. The importance of monitoring the clinical state of people at home improves models used to predict future vital signs and clinical events [

38].

In a model based on MAS for managing and evaluating the interaction between devices, a dynamic trust source is created using assessments, which helps to eliminate invalid agents and devices [

39]. A multi-agent system can enhance accuracy and improve results for patients, simplifying operations and clinical decisions [

40]. A multi-agent system is used to make the devices connect and cooperate in order to make decisions flexibly and independently, using learning models to meet patient needs [

41]. A multi-agent system can deal with a linguistic model for prior authorization in healthcare, where a special agent checks a patient’s clinical records and compares them with clinical instructions to provide justifications and interpretations based on decisions [

42] (

Table 1).

Previous studies have relied on multiple methods to classify and analyze data and have faced multiple challenges in converting this data into real-time and reliable decisions for clinical cases due to a lack of data quality verification. There have also not been many investigations into response times, which are important in healthcare. Consequently, this study provides a new model, PLPF-MAS, for analyzing and classifying data, real-time decision-making, providing recommendations, and reducing response times. This model is classified using observed and passive features based on a multi-agent system, and the results are compared with studies by [

35,

38].

2.1. The Taxonomy of the Methods

Healthcare methods for monitoring and diagnosis.

2.1.1. Signal-Based Analysis

2.1.2. Image/Video-Based Analysis

Patient Movement and Posture Detection [

32]: This method performs non-invasive automated patient discomfort monitoring. It employs the Mask-RCNN method, which extracts key points from the patient’s body using an IP camera.

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) [

46]: This achieves real-time HAR using data from a smartwatch. It uses a pre-trained ResNet50 deep neural network to classify images based on histograms generated from the raw accelerometer and gyroscope data.

2.1.3. Combined Data Analysis

Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy Detection [

47]: This method aims to detect hypertensive disorders during pregnancy early. It employs an electronic prototype that acquires blood pulse and weight data transmitted via Bluetooth and processes it using Random Forest.

This taxonomy categorizes the methods based on the type of data they analyze and further breaks down the specific techniques and aims within each category, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Initial Analysis

Vital signs are interrelated and provide important information that we can utilize to predict future clinical states [

32]. For example, when the heart rate is abnormal, it indicates a problem in the heart, possibly because of low blood pressure; shock; congestive heart failure; or a benign cause, such as exercise. It is difficult to determine the reason without checking all vital signs. Consequently, it is important for specialists to continue monitoring vital signs.

In this study, two datasets were used for a reliable comparison with previous studies [

35,

38]. The first dataset used in [

38] is the MIMIC-II database of the MIT physio bank archive [

48], which contains 1023 patient records. This number represents the total number of patient records, which also contain vital sign records. Because these vital signs are presented in a continuous time series (extending over hours and days at unequal intervals), we separated each patient record using a segmentation method. These cases were solved by dividing them into fixed-length segments and recording clinical events every 30 min [

38], as shown in

Table 2. We used the vital sign values in

Table 3 and classified them independently either as normal or abnormal cases, depending on the clinical event. Thus, from all patients, we created a new matrix, L, containing X rows and Y columns, where X is the number of samples after recording vital signs every 30 min for all patients. Consequently, new samples were created (2420 rather than 1023) to train the proposed model more efficiently, where multiple samples are taken from each patient’s records. In

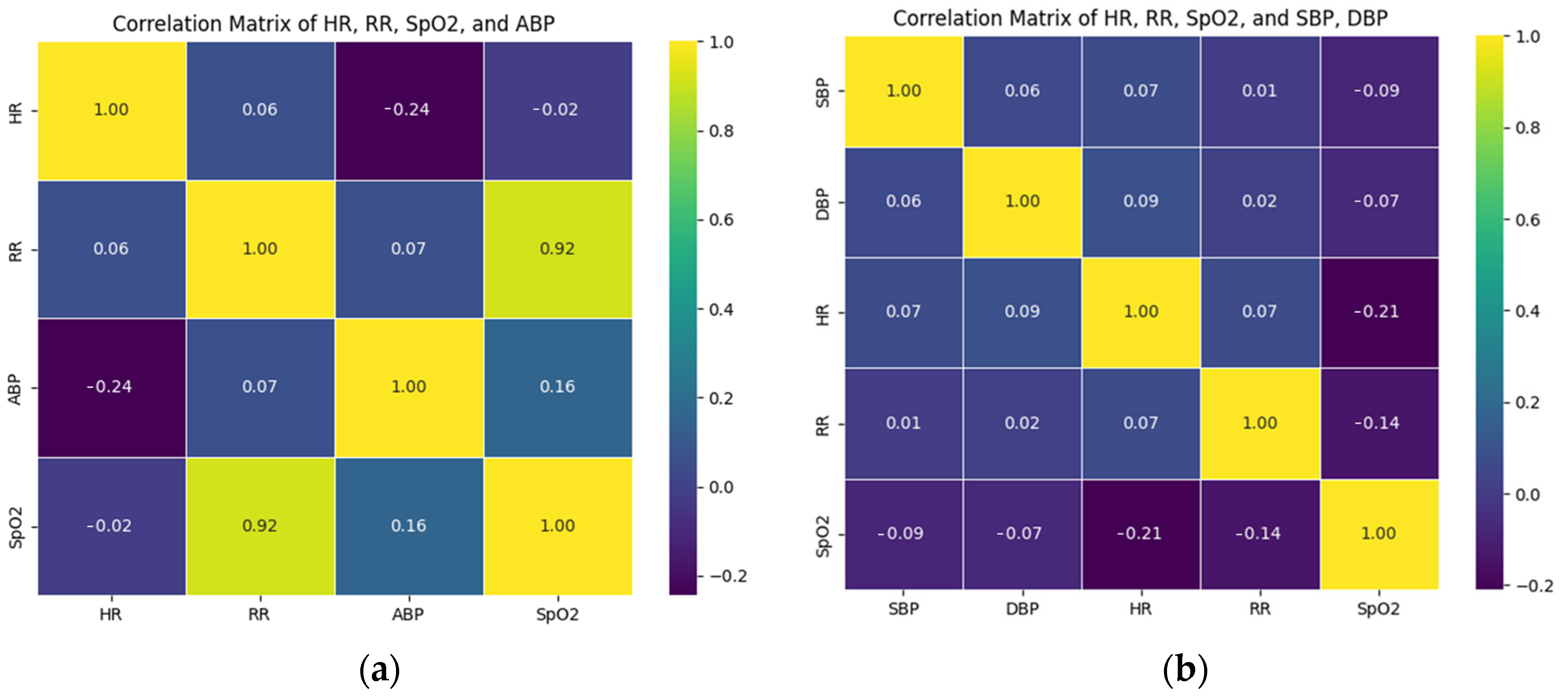

Figure 2a, each square represents a correlation coefficient between two corresponding variables on the horizontal and vertical axes of the MIMIC-II dataset, and the numbers within are the actual correlation coefficient values. This makes the relationship between HR, RR, ABP, and SpO2 easy to discern. The second dataset is the EHR dataset [

49], used in [

35], which contains 10,000 patient records. This dataset is also a continuous time series of vital signs (HR, RR, SpO2, and BP); thus, we separated each patient’s records according to the segmentation method. In

Figure 2b, each square represents the correlation coefficient between its two corresponding variables on the horizontal and vertical axes of the EHR dataset, and the numbers within are the actual correlation coefficient values. This makes the relationship between HR, RR, SpO2, SBP, and DBP easy to discern.

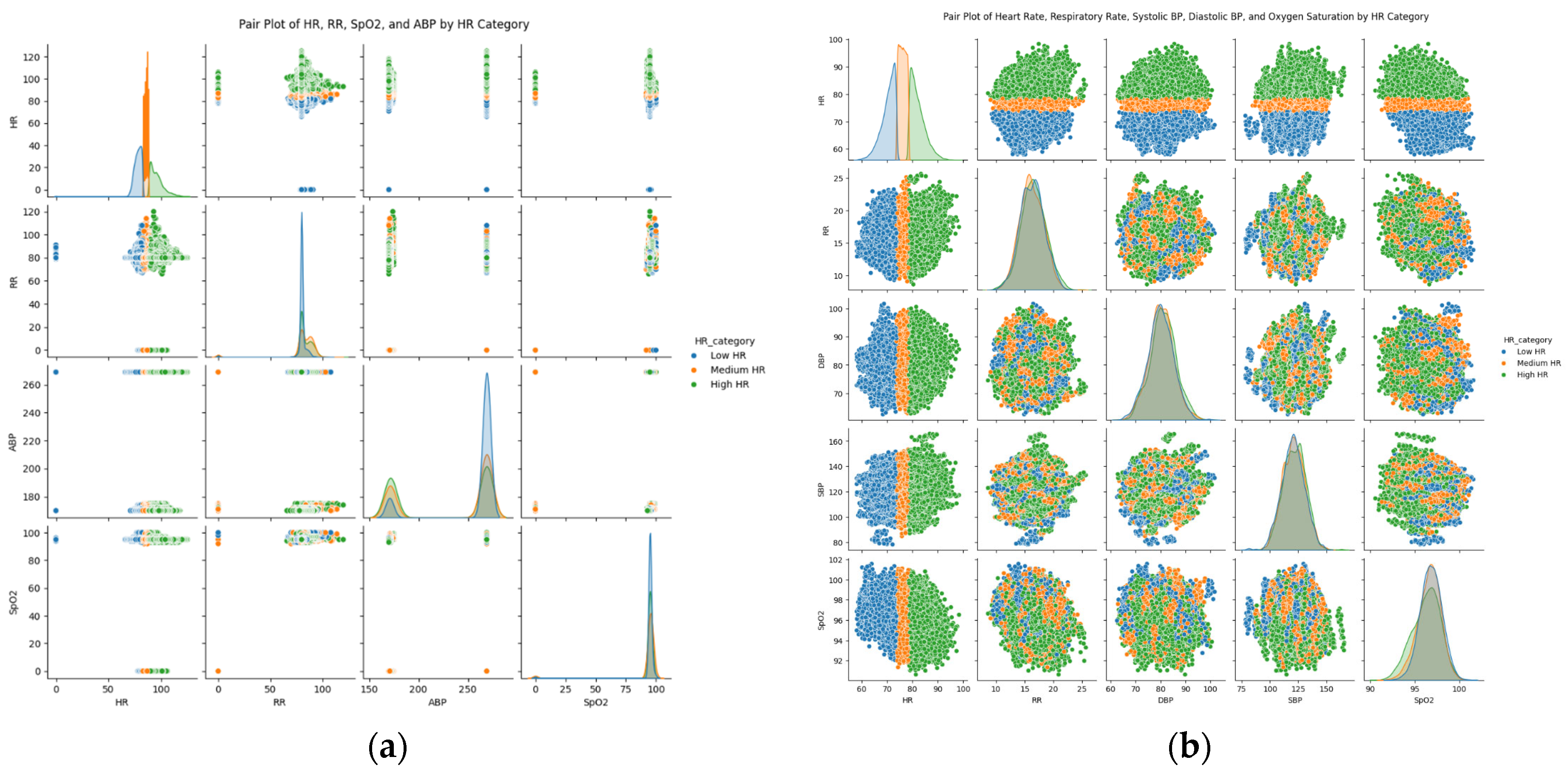

Figure 3a,b present the distributions of each type and how these distributions overlap or diverge across different heart rates, showing complex relationships and types that may not be determined through numerical correlations, especially with influential differences, such as HR of the MIMIC-II dataset and the EHR dataset.

Clinical States and Vital Signs

To detect early clinical signs, we considered four vital signs (HR, RR, BP, and SpO2) dependent on six bio-signals, drawn from the MIMIC-II and EHR datasets (

Table 3) [

33]. These vital signs vary based on medical conditions, sex, age, etc. For example, the blood pressure of an elderly person in a normal case differs from that of a young person in an abnormal case. However, the common normal range has been determined by medical science researchers [

35,

36,

37], as shown in

Table 2. We can associate tachycardia and bradycardia with heart rate (HR) and hypotension; blood pressure (BP), tachypnea, and bradypnea with respiratory rate (RR); and hypoxia with blood oxygen saturation (SpO2).

3. Methodology

Through a data agent, our new model takes data from a healthcare dataset stored in the cloud through IoT devices. It then processes the data, divides it depending on the requests of other agents, and sends it to the LR and AE agents. The LR agent evaluates the data quality and confidence in statistical operations; it then processes in parallel with the AE agent, which reduces feature dimensions and sends the compressed data stored in a bottleneck to the HHM agent to enhance its performance. Then, the HMM agent decreases noise, extracts features, performs time modeling, and predicts states. The coordinator agent documents all phases that lead to the final decision. It also uses

and risk probability rules for the final clinical status to provide important recommendations and sends notifications to a supervisory agent regarding error or risk states. Finally, the supervisory agent decides when the model must be retrained, corrects the model when it fails, manages policy, and records all decisions. Consequently, the multi-agent system achieves smart integration and makes a final decision in real time. Its components are implemented in parallel (not sequentially when using LR or AE-HMM without MAS), which increases the response time (each LR and AE agent is implemented at the same time); this is very important in real-time decision-making. The agents operate independently, so if one fails (the sub-agent), the others can complete their tasks; without MAS, each individual failure can cause the system to fail entirely, as shown in

Figure 4. The steps of multi-agent systems are detailed in

Section 3.2. For the model’s practical applicability, two real datasets are used. The first dataset was collected from the MIMIC-II database of the MIT physio bank archive, containing 1023 patient records [

48] used by [

38] to establish their baselines. Conversely, the EHR dataset was used by [

35] to establish their baselines. We used two datasets to compare our model results for better reliability.

3.1. Predicting and Labeling Data Using the Passive Features Model (PLPF)

The proposed model predicts the best outcomes from the input data, using LR for linear data. To make real-time decisions, an AE with an HHM compresses the data, extracts important features, and processes it based on time series and MAS.

3.1.1. Linear Regression

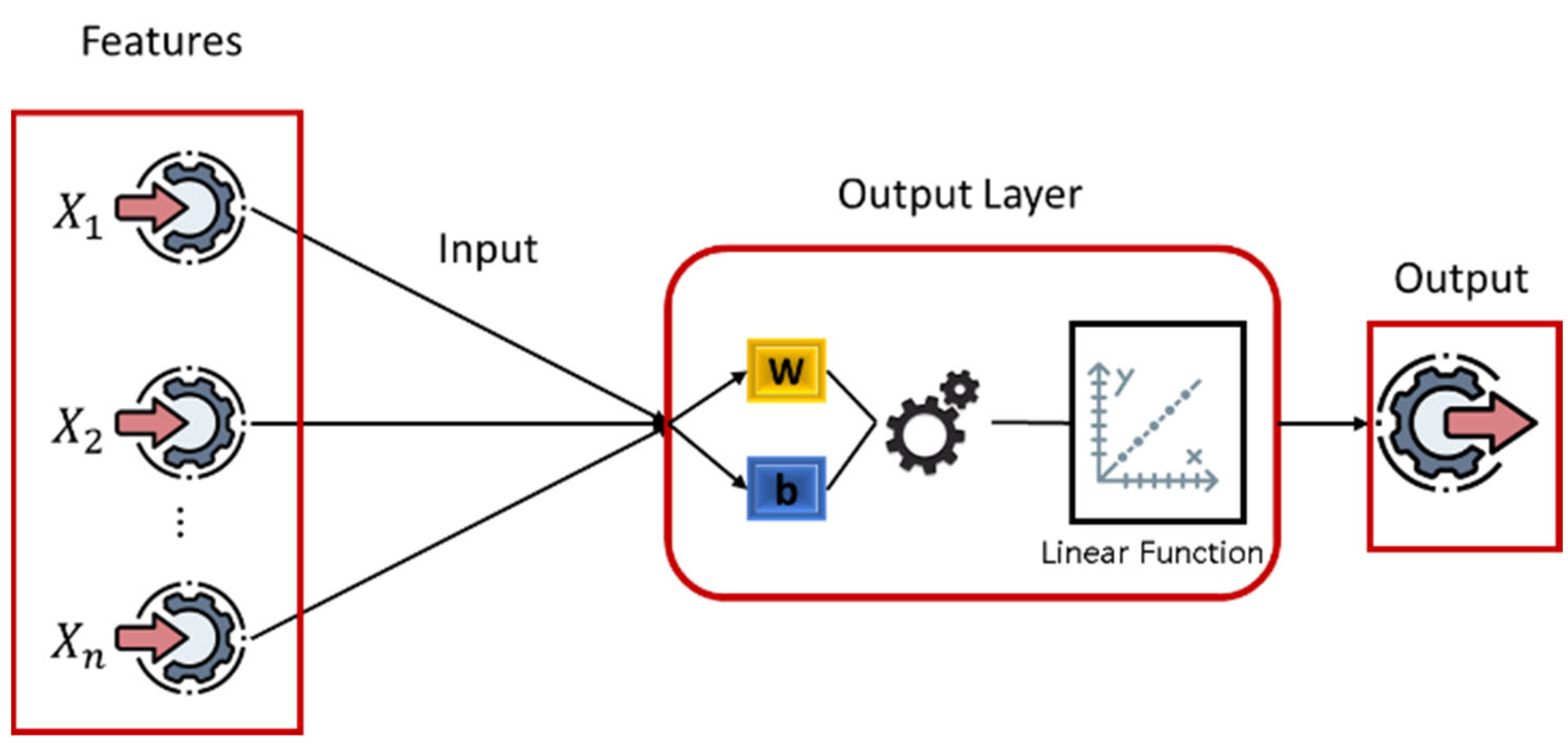

LR establishes a relationship between the target variable and one or more independent variables to determine the best model for later use, as shown in

Figure 5 and Algorithm 1. In this advanced model, the LR model processes the data in parallel with the AE-HMM model, where the LR model adds a completely independent layer to achieve high reliability by calculating the risk-flag. When the LR model finds the best relationship between the input data (HR, RR, SpO2, and ABP) and the probability of risk, the data is considered accurate when making a final decision. The model then evaluates a linear relationship among current data. LR with a multivariable can be defined as

where

is a hypothesis for a linear regression with a multivariable, and (

) is the bias. For the convenience of notation,

.

Next, we need to find the transform for the

matrix:

:

In Equation (2), we multiply the matrix by the () matrix to determine the hypothesis for linear regression with a multivariable ().

The cost function depends on the following equation:

where (

) is the number of features,

is the input (features) of the

training samples, and

is the value of feature

in the

training samples.

| Algorithm 1 Linear Regression |

Input: Training data X (features), y (target)

Output: Weight vector, w

Initialize weights, w, randomly or with zeros.

Repeat until convergence:

y_pred = X · w

error = y_pred − y

gradient = X^T · error

w = w − learning_rate ∗ gradient

Return w |

3.1.2. Autoencoder Model and Hidden Markov Model (AE-HMM)

The HMM model is strong when it deals with short correlations, but it faces challenges when it deals with complex models with noise. To enhance model performance, the AE model can simultaneously process data to decrease noise, extract features, perform time modeling, and predict states by merging these models (AE-HMM).

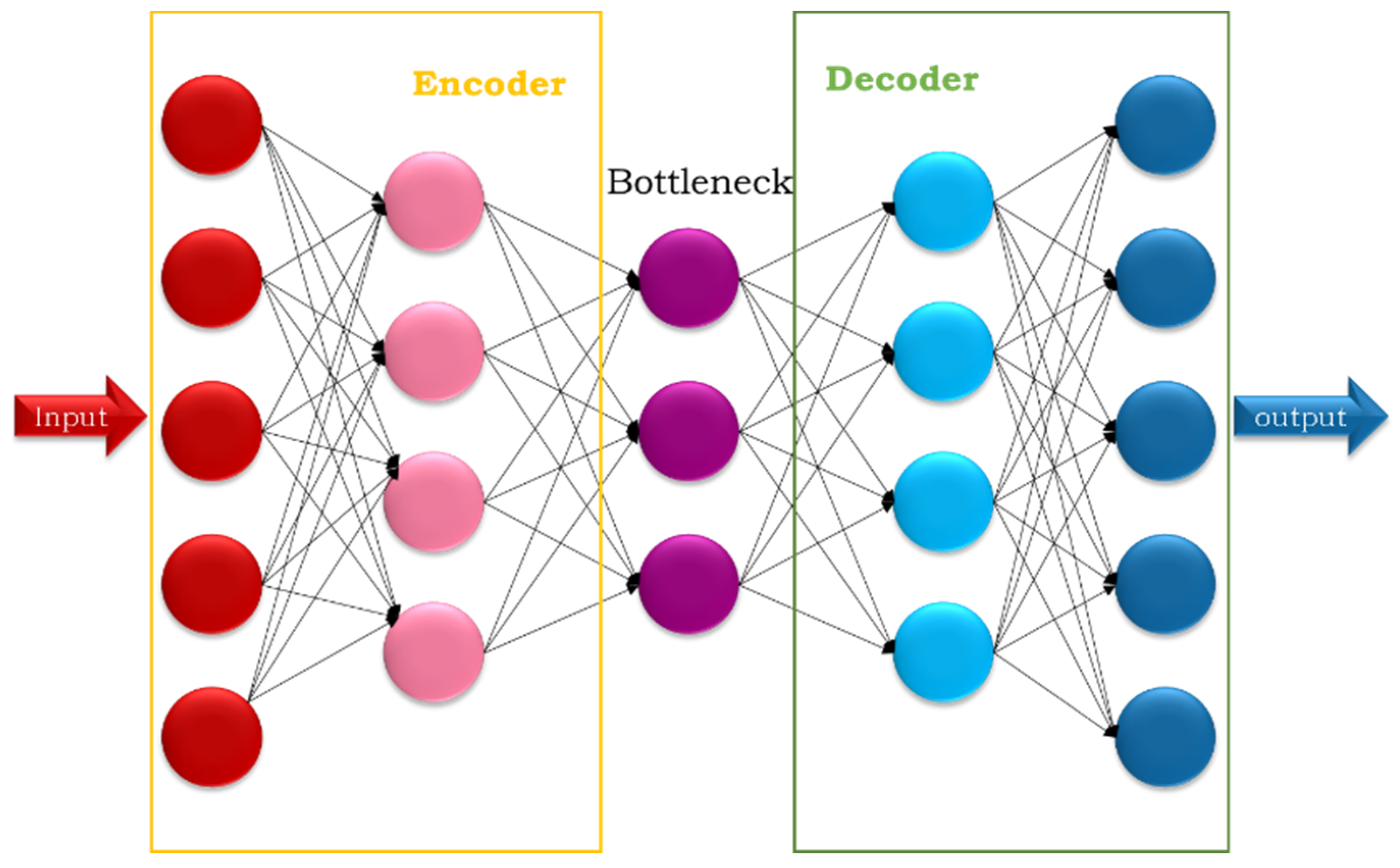

Autoencoder Model (AE): This is an unsupervised deep learning technique widely used in data analysis and processing. It is trained to reconstruct the input data, which helps extract important and hidden features. The simple autoencoder goes through several stages: encoding in Equation (4), which teaches it to compress the input; bottlenecking, which stores the encoded representation of the input; and decoding in Equation (5), which teaches it to reconstruct the output from the bottleneck, as shown in

Figure 6. Reconstruction loss measures the error between the input and output (Equation (6)).

where (

) is the activation function of the encoder, (

) is the prediction weights (predicted by machine learning) in the encoder step, (

) is the original input feature, (

) is the theta (often called bias) value predicted via machine learning in the encoder step.

where (

) is the activation function of the decoder, (

) is the prediction weights (predicted by machine learning) in the decoder step, (

) is the latent data that is saved in a bottleneck, and (

) is the theta (often called bias) value predicted via machine learning in the decoder step.

Reconstruction loss is calculated using several methods, including mean squared error:

where (

) is the mean square error, (

) is the number of data points,

) is the observed value, and

is the predicted value.

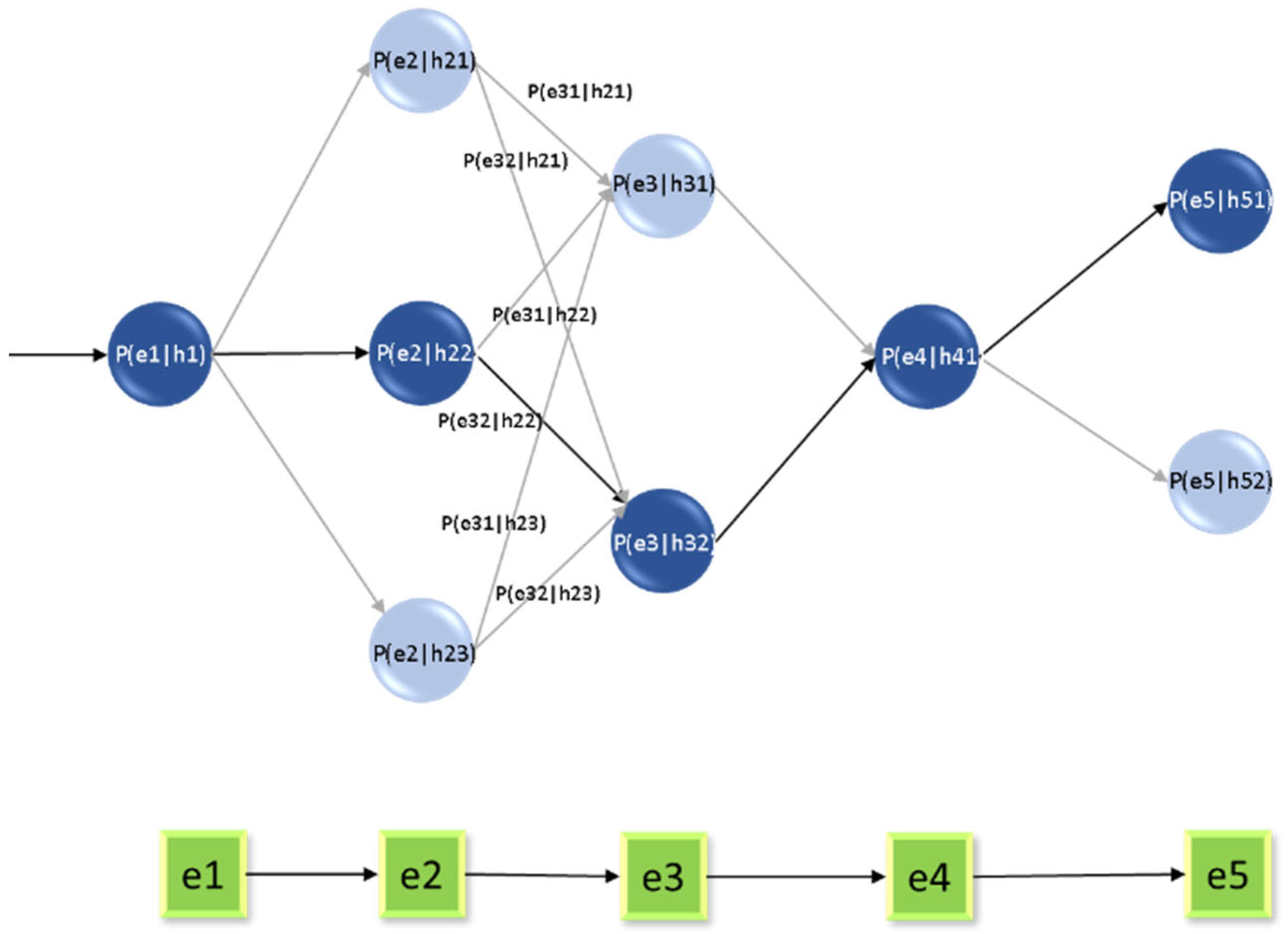

Hidden Markov Model (HMM): This is a statistical model within the machine learning framework that creates a relationship between a series of observations and the hidden data. This name was chosen because it is usually applied to systems where the basic processes are hidden or unknown. It tries to understand processes that occur through the effects of a series of variables. It is used either for prediction or classification and consists of two types of data: hidden states, basic variables that generate observed data but cannot be observed directly, and observations, Basic data that can be observed and processed to create a relationship between these data. Two types of probabilities are used: transition probabilities, the probability of moving between different hidden states, as in Equation (7), and emission probabilities, the probability of inferring certain outcomes in hidden cases, as in Equation (8).

The hidden Markov model is used on the latent data resulting from the AE model after it compresses the data and extracts the important features. This is inferred from Equation (4), where the data are stored in the bottleneck (

). The difference square between the original and compressed data is also called the loss data (

), which is calculated from Equation (6).

and

are then combined into one variable,

. This is calculated using Equation (7) to analyze the temporal relationship with the hidden states (h), which are inferred through the HMM model (

Figure 7) and Algorithm 2.

The probability distribution of hidden cases (

) is found according to the following mathematical equation:

where (

is the current hidden status, (

is the previous hidden state, and

is the probability of transition from state (

) to state (

).

The probability distribution of the observed cases (

) is found according to the following mathematical equation:

where (

is the observed and reminder data at time (

), (

is the hidden data at time (

), and (

is the observed probability

in state (

).

We can find the joint probabilities using the following mathematical equation:

We can find the Log-likelihood loss using the following mathematical equation:

where (

) is the log-likelihood loss, (

) is the sequence of observed data, and (

) is the sequence of hidden data.

The Viterbi algorithm is used to sequence the most probable hidden state, which provides the sequence of information. This can be defined by the following equation:

The forward–backward algorithm comprises a forward algorithm used to calculate the total probability of sequences, as in Equation (13), and a backward algorithm used to determine the probability of viewing the rest of the information sequence, as in Equation (14).

| Algorithm 2 Autoencoder–Hidden Markov Model. |

Input: Sequential data X

Output: Hidden states sequence and trained AE-HMM

Step 1: Train Autoencoder

Initialize encoder and decoder networks.

Repeat for several epochs:

z = Encoder(X)

X_reconstructed = Decoder(z)

loss = ReconstructionLoss (X, X_reconstructed)

Update encoder and decoder parameters to minimize loss

Step 2: Train HMM on latent representation

Z = Encoder (X) # Get latent features

Initialize HMM parameters (A: transition, B: emission, π: initial state)

Use Baum–Welch algorithm to train HMM on Z

Return trained encoder, decoder, and HMM parameters |

3.2. Multi-Agent System (MAS)

The multi-agent system merges the models (LR; AE-HMM) to convert the results from models into real-time action. This improves the model response time and provides an important clinical recommendation depending on the PLPF model. It divides the complex task of the model into subtasks and appoints an agent to each subtask. The coordinator agent interacts with all agents to make the final decision as show in Algorithm 3. The suitable agents of the model are determined as follows:

Data Agent: This is the only source that provides data for the model, which obtains the healthcare dataset previously stored in the cloud. It then processes the data, divides it depending on the requests of other agents, and sends it to the LR and AE agents. It also notifies the agents if the data is ready and notifies the supervisory agents if their connection to the data source fails.

Linear Regression Agent (LR agent): This is also called a reliability agent. It evaluates the linear relationship quality between the data and the risk-flag. The actions of this agent are divided into several steps, initially taking the data and risk-flag and dividing the data into training and testing sets to avoid bias. Then, it trains the LR model on the training data and ensures that the training process occurs in parallel with AE-HMM model training, followed by the measurement and verification phase. It does so to predict bias in the training model and to calculate the

value by comparing it with the threshold value, as in [

38]. This is followed by the communication phase, where the agents connect with the coordinator agent. The LR agent interacts with the coordinator agent to obtain recommendations and warnings depending on the

value. It also interacts with the supervisory agent to retrain the model (LR) again if the

value decreases. Therefore, the LR agent is important in making the final decision by declining weak evidence, thus decreasing the

value. When the

value is compatible with the HMM, the warnings are more reliable.

Autoencoder Agent (AE agent): This is also called the feature engineering agent. It obtains data from the data agent and then reduces the feature dimensions (ABP, HR, RR, and SpO2) and decreases noise based on the AE model, which acts in two steps: the encoder step, as in Equation (4), which leads to compressed features (z) that are sent to the HHM model to enhance its performance, and the decoder step, as in Equation (5), which leads to decompressed features (y_de) to used it in calculate error value, as in Equation (6). This determines the model’s capability in terms of feature reconstruction, consequently ensuring that the model can reliably reduce feature dimensions sent to the HMM model. Finally, the AE agent connects to the coordination agent and the supervisory agent to simplify the final decision.

Hidden Markov Model Agent (HMM agent): This is also called the prediction agent. It models time series to predict the feature state of a patient (the probability of a future state of risk). It deals with transition probabilities, as in Equation (7), and emission probabilities, as in Equation (9), providing an accurate description of the data. The HMM agent processes the data with the Baum–Welch algorithm. This trains the model using incoming compressed data from the AE agent. It then calculates the probability of the created data from the training model and the states of the model using the backward–forward algorithm, as in Equations (12) and (13). It predicts the results based on the most likely value of the hidden state, which leads to a sequence of information using the Viterbi algorithm, as in Equation (11). Consequently, the HMM agent connects to the coordinator agent to send its prediction and risk probability values. It also sends the supervisory agent the final state reports (failure/success) to make the final decision.

Coordinator agent: This documents all phases that lead to the final decision, using

and risk probability rules for the final clinical status. It supervises and administers the data transfer agents, provides the notification, and manages the time limits on completing the processes of the other agents. It also applies logical tools to achieve all the conditions in

Table 3 to provide important recommendations, and makes the final real-time decisions if the workflow is normal. In error or risk states, the coordinator agent sends a notification to the supervisory agent to fix the problem.

Supervisory agent: This is the strategic structure of the model. It protects the model from any risk and maintains its stability, performance, and activities. It decides when the model must be retrained, corrects the model when it fails, manages policy, and records all decisions. For example, if the value is suitable, the process is stored in its log; otherwise, it sends a notification to retrain the LR agent.

| Algorithm 3 Multi-Agent System (MAS).

|

Initialize Dataset D, Data Agent

Initialize LR Agent

Initialize AE Agent

Initialize HMM Agent

Initialize Coordinator Agent

Initialize Supervisory Agent

Define Recommendations:

TTHH→“Critical: Tachycardia + Hypotension + Tachypnea + Hypoxia. Immediate intervention.”

BTHH→“Serious: Bradycardia + Hypotension + Tachypnea + Hypoxia. Cardiovascular support required.”

TTTH→“Warning: Tachycardia + Hypertension + Tachypnea + Hypoxia. Monitor BP and provide oxygen.”

THBH→“Danger: Tachycardia + Hypotension + Bradypnea + Hypoxia. Respiratory failure risk.”

NNNN→“Normal: All vitals stable. Continue routine monitoring.”

Data Agent Stage

for each raw_sample in D:

x = Data_Agent.preprocess (raw_sample)

Training Stage

for each (x, label) in D:

LR_Agent.train (x, label)

latent = AE_Agent.encode (x)

AE_Agent.train (x, latent)

HMM_Agent.train (latent, label)

Inference Stage

for each x in D:

x_clean = Data_Agent.preprocess (x)

lr_out = LR_Agent.process (x_clean)

latent = AE_Agent.encode (x_clean)

recon = AE_Agent.decode (latent)

hmm_state = HMM_Agent.forward (latent)

message = {“lr”: lr_out, “latent”: latent, “recon”: recon, “hmm”: hmm_state}

predicted_state = Coordinator_Agent.classify (message)

recommendation = Supervisory_Agent.provide_advice (predicted_state, Recommendations)

output predicted_state, recommendation

end for |

4. Results

This section discusses hardware, simulation, and evaluation metrics for the PLPF model, consisting of LR, AE, and HMM; the model results; and a comparison with previous work.

4.1. Hardware and Simulations

The dataset processing and simulation were performed with the Google Colaboratory (Google Colab) platform, using the Python version 3.12 programming language. The simulation was run on standard hardware, available for free on Google Colab. The hardware comprises an Intel Xeon CPU, 12 GB of system RAM, and a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) that runs on GPU acceleration (NVIDIA Tesla K80, T4, V100), provided by Colab for free. The effective calculations were performed using Python libraries such as NumPy, TensorFlow, pandas, sklearn, and matplotlib.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

Automatic evaluation criteria are used to evaluate the performance of the proposed system. The model’s performance can be evaluated using many metrics; this depends on the evaluation parameters, which are true negative (TN), true positive (TP), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN). In this study, the following parameters were used.

4.2.1. LR Agent Evaluation Metrics

The LR agent evaluates the quality of metrics to ensure the model’s reliability. The most important evaluation metric is the R-square (

), also called the coefficient of determination. This is a statistical measure that represents the proportion of variance between a dependent variable that is explained by one or more independent variables. The agent measures the reliability through the

and sends the result to the coordinator agent to provide it with the model’s reliability. When the value is closer to 1, the model has high reliability. When the value is closer to 0, the model has low reliability, or the linear relationship is very weak. The

is calculated using the following equation:

where (

) is the residual sum of squares, and (

) is the total sum of squares.

4.2.2. AE Agent Evaluation Metrics

The most important measure used to train and evaluate the performance of the AE model is the mean squared error (MSE), that is, the mean squared difference between the resulting values and the original values, as in Equation (6). A low value for this measure indicates reliability in reducing original feature dimensions and the model’s capabilities in feature reconstruction, and vice versa.

4.2.3. HMM Agent Evaluation Metrics

The HMM agent predicts risk occurrence and focuses on true positive risk predictions, which are measured by the following metrics:

Sensitivity (Recall): This measures small changes that cause large changes in value and is calculated using the following equation:

Specificity: This predicts true negativity for all available categories and is calculated using the following equation:

Accuracy: This is used to measure the percentage of correct predictions relative to the total number of predictions and is calculated using the following equation:

Precision: This finds the true positive ratio of the total positive predictions and is calculated using the following equation:

F1-Score: This balances both measures and finds the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It is calculated using the following equation:

AUC-ROC: The model can distinguish between classes represented by the area under the curve, which is calculated using the following equation:

AUC-PR: This is the integral of precision (

) with respect to recall (

) through the recall range. It is calculated using the following equation:

4.3. Training

The PLPF model uses a multi-agent system consisting of six agents to perform four major stages: data processing, sub-model training (LR, AE, and HMM), merging the results of the coordinator agent, and managing the policies of the supervisory agent. In the data processing stage, the data agent provides vital data by cleaning and extracting the time series. Then, in the sub-model training stage, the LR agent trains the LR model to connect vital values to five clinical states, the AE agent trains the AE model to compress based on reconstruction loss, and the HMM agent uses the compressed data from the AE agent to train time patterns and transitions. Then, the coordinator agent merges the results from those agents to make a final real-time decision, determine clinical states, and obtain recommendations. Finally, the supervisory agent monitors the agent’s performance and sends a warning if any errors or risks are detected.

4.4. PLPF-MAS Model Performance

The multi-agent system achieves high prediction accuracy in clinical states by merging its results with those of the LR and AE-HMM through the coordinator agent. In testing, the model has a strong ability to differentiate between five clinical states (THTH, BHTH, TTTH, BTHH, THBH, and NNNN). The coordinator agent achieves higher accuracy than the agents because it receives its information from three agents. The model achieves an accuracy of 98.4%, a precision of 95.3%, a sensitivity of 99.2%, a specificity of 99.1%, an F1-Score of 97.1%, and an R2 of 98%, and it is comparable to HMM-PCA [

38] based on the MIMIC-II dataset, as shown in

Table 4.

Furthermore, PLPF-MAS achieves an accuracy of 93%, a precision of 92%, a recall of 94%, an F1-Score of 93%, an AUC-ROC of 94%, and an AUC-PR of 89%, and it is comparable to LSTM [

35] based on the EHR dataset, as shown in

Table 5. This indicates the PLPF-MAS model outperforms both HMM-PCA and LSTM in accuracy and reliability; the ability to determine normal and abnormal cases and avoid false negatives and false positives; and the ability to separate positive and negative categories.

The LR agent checks the data and calculates the , which measures data reliability and the interpretability of the statistical samples. = 98% in all clinical cases, indicating that the data agent successfully provides high-quality data and segments data with regularity. In the parallel phase, the AE-HMM agent implements the prediction and classification processes and calculates the evaluation metrics (an accuracy of 98.4%, a precision of 95.3%, a sensitivity of 99.2%, a specificity of 99.1%, an F1-Score of 97.1%). This indicates that the AE agent effectively compresses data and reduces noise, which enhances the HMM agent’s implementation during all clinical cases and leads to good results. The R2 value indicates high-quality statistical data, while the accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-Score indicate model strength. However, all are important, and they are sent to the coordinator agent for real-time decision-making.

4.5. Model Recommendations

After model training and performance, the coordinator agent merges the results. The HMM agent measures the most important risk probabilities, and the LR agent measures the statistical reliability. This ensures the validity of warnings, decreases false alerts, and detects data skewness. Consequently, the model uses rules to convert these alarms into recommendations. It can also use Prisk and the

to give recommendations based on the five clinical states. If Prisk is very low and the

is very high, the model interprets an NNNN state and recommends the following: Continue routine monitoring. Patient’s vital signs are within normal limits. If Prisk is high, and the

is high, it interprets a THTH state and recommends the following: Administer IV fluids and monitor blood pressure closely. Consider vasopressors if hypotension persists. If Prisk is very high, and the

is high, it interprets a BHTH state and recommends the following: Initiate cardiac pacing or atropine administration. Monitor for signs of shock and improve blood pressure. If Prisk is medium to high, and the

is low, it interprets a TTTH state and recommends the following: Immediately assess airway and breathing. Provide oxygen; consider intubation. Address tachycardia and hypotension with fluids and vasopressors. If Prisk is very high, and the

is high, it interprets a THBH state and recommends the following: Extremely dangerous/immediate warning (see

Table 6).

This indicates that the system can identify cases that need to be monitored, such as TTTH, and cases that require immediate intervention, such as THTH and BHTH. The normal values of the four vital signs (HR, RR, BP, and SpO2) depend on six bio-signals (

Table 3) and are used to detect early clinical signs [

33]. The normal range is determined by medical science researchers [

36,

37], as shown in

Table 2, which is very important in the healthcare field because prediction results are represented by numerical values [

35,

38] and must be readable for AI technicians. Therefore, a human doctor cannot understand this prediction result. Consequently, we used MAS to make the result clear to physicians. Our recommendation will help doctors to make final decisions, depending on their experience in the medical field.

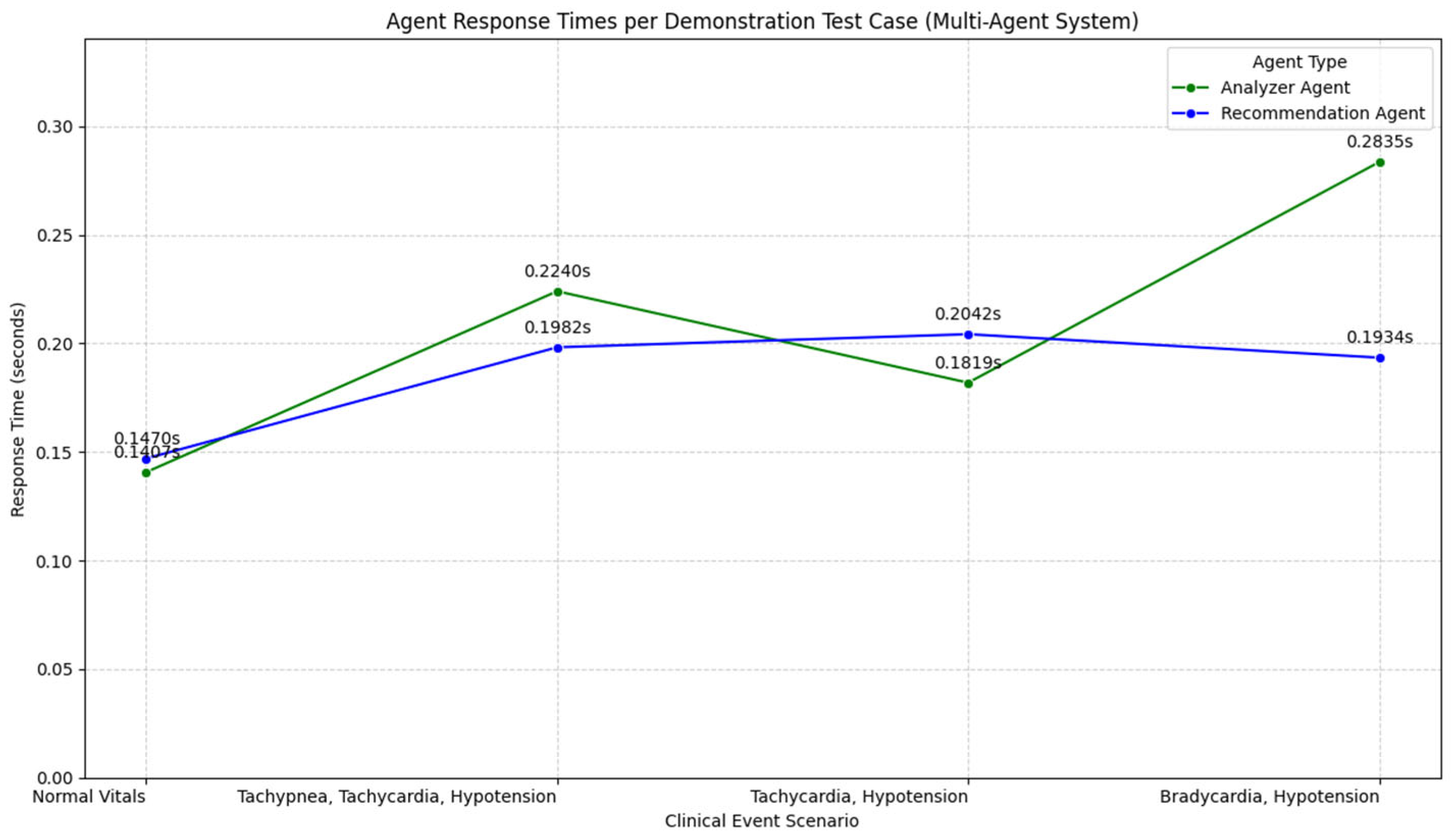

4.6. PLPF-MAS Response Time

The PLPF-MAS response time is the period during which new vital sign data are read by the coordinator agent to make a final decision. This interval must be very short (less than 1 s) to ensure the work is performed in real time. It is calculated by adding the time of data retrieval to the longest execution route among parallel agent routes, as defined by the following equation:

Then, the fusion time and the final format are added. Especially when dealing with healthcare, time reduction is very important in ensuring that any warnings are received accurately. This allows medical staff to intervene in time, as shown in

Figure 8.

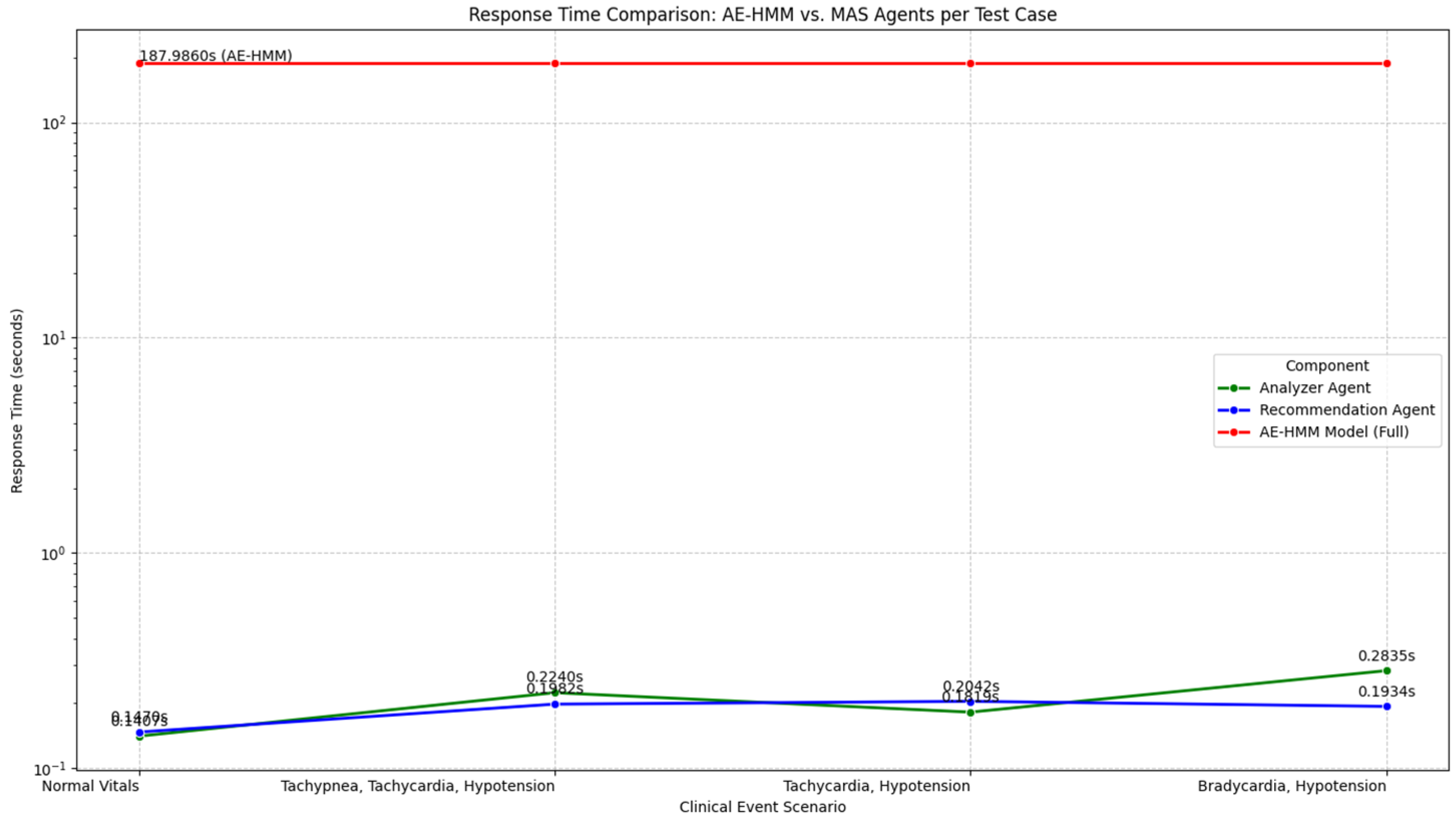

The time of the AE model is about 187 s. The MAS analysis time decreases to 0.2365 s, and the MAS recommendation time decreases to 0.2132 s. This is achieved using Python version 3.12 in Google Colab and an Intel Xeon CPU with 12 GB of system RAM. This reduces the MAS response time, indicating a very strong and efficient model. While the AE-HMM can take time to train and predict, the MAS can provide the user with a very fast response. This indicates that the MAS is suitable for the PLPF model.

Figure 9 shows the response times of AE-HMM and the MAS when dealing with clinical states. The figure indicates that for clinical states and recommendations, the MAS is highly efficient and responsive. This makes it suitable for real-time clinical decision support systems.

Through study and comparison with previous works (

Table 7), we have created a smart healthcare model characterized by strong flexibility and reliability, an ability to deal with large datasets, and a short response time. It can provide recommendations and warnings regarding risks and predict clinical states with high accuracy.

5. Discussion

Previous methods face several challenges in analyzing complex medical data in smart healthcare, including the inadequacy of simple linear relationships, difficulty in handling high-dimensional data and noise, and difficulty in capturing nonlinear patterns and latent representations. These methods also have problems in modeling the time evolution of predictions. The new method (PLPF-MAS) represents a robust solution for real-time clinical risk prediction problems. It uses the Google Colab platform to process and simulate the MIMIC-II and EHR datasets using the Python version 3.12 programming language, an Intel Xeon CPU with 12 GB of system RAM, and a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU).

It is distinguished from traditional methods in its advanced system, which combines the activities of several agents and the intelligent distribution of responsibilities among them. The model depends on a linear regression agent to calculate the

to measure its reliability and reduce false alerts (false positive states), thus increasing its credibility with medical staff. The model also depends on an AE agent to measure its ability to compress data, reduce data noise, reconstruct data, and send compressed data to the HMM agent. This allows it to make predictions and calculate the probability of risk, allowing it to track the transmission of hidden states, as shown in

Figure 5. For example, this may involve updating the patient’s state from a normal state to a risk case. In this situation, the coordinator agent detects risk depending on the Prisk and

values, providing warnings and recommendations based on clinical states. All of these records are sent to the supervisory agent to record all processes and to retrain the model’s management procedures based on risk states. This model’s structure can accurately identify subtle changes or unusual patterns in vital signs over time, enabling early intervention and improved understanding of a patient’s condition. This helps in uncovering subtle stages of disease progression or recovery that may not be apparent in static individual measurements. The model deals with complex data and overcomes the challenges of high-dimensional, noisy, and time-related healthcare data. These features allow the model to make clinical decisions more accurately and successfully clarify recommendations to medical staff.

6. Limitations

The proposed method does not include an analysis of patient demographics, such as age and sex. Furthermore, we did not study the security of the patients’ information against adversarial attacks, which can lead to data theft and alterations. Moreover, we did not study the privacy of the data between various agents in the MAS system. This study did not apply to real-life integration steps in operating systems or the planning of future clinical trials.

7. Conclusions

Previous studies have shown that central processing units (CPUs) experience many challenges in data analysis, specifically in converting data into real-time and reliable decisions for healthcare activities in smart cities. The HMM model has many problems that reduce its effectiveness, such as complex healthcare datasets, the assumption that the current observation depends on the current hidden state only, and observations that are conditionally independent of the hidden states. However, this assumption does not apply to real healthcare data, where prior observations can directly influence subsequent observations. Furthermore, nonlinear relationships are difficult to address, processing complex data is difficult, the number of hidden states is difficult to identify, and there are problems with overfitting and sparsity.

When performing experiments on the same datasets used in other studies, the proposed PLPF-MAS model outperformed the previous methods. This is due to the PLPF-MAS model’s use of a linear regression agent, which helps to address direct linear relationships and to calculate reliable statistics. It then uses an AE agent in parallel with an LR agent, which generates robust, nonlinear feature representations for complex and noisy data. The AE agent-compressed data is then used to model temporal dependencies and to detect hidden states and patterns as inputs to the HMM agent, making it an integrated model that outperforms the HMM alone in analyzing and processing complex healthcare data.

The PLPF-MAS model achieved an accuracy of 98.4%, a precision of 95.3%, a sensitivity of 99.2%, a specificity of 99.1%, an F1-Score of 97.1%, and an of 98%. The previous method recorded an accuracy of 97.4%, a precision of 92.36%, a sensitivity of 98.51%, a specificity of 97.96%, and an F1-Score of 95.34%. Furthermore, the PLPF-MAS model uses multiple agents, facilitating task distribution between these agents and making the system more flexible. As such, it is an integrated model that outperforms the LSTM in analyzing and processing complex healthcare data for decision-making. The PLPF-MAS model achieved an accuracy of 93%, a precision of 92%, a recall of 94%, an F1-Score of 93%, an AUC-ROC of 94%, and an AUC-PR of 89%. The previous method recorded an accuracy of 87%, a precision of 89%, a recall of 86%, an F1-Score of 87%, an AUC-ROC of 92%, and an AUC-PR of 88%.

8. Future Work

Our future research will involve hardware that can collect real data from patients and analyze it by using the PLPF MAS model. We will also evaluate the model’s security and privacy regarding information. We will use integrated interpretability techniques, such as Shapley values, to provide interpretations for the decisions of the HMM agent based on compressed data from the AE agent; this will increase the reliability of medical staff regarding the model’s decisions. Our future study will also implement the model using cloud or edge computing.

Author Contributions

N.F.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, original draft preparation, H.K. and H.A.: writing review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For this study the ethical review and approval were waived, as it utilized the MIMIC-II database, which contains de-identified data. The (N.F.A.) author has completed the required Human Research Subject Protections training (CITI Program) and followed all protocols specified in the Data Use Agreement (DUA).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the study utilized a de-identified, retrospective database. All data were anonymized in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) standards to ensure patient privacy.

Data Availability Statement

In this study the used data obtained from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-II) database. The PhysioNet gave the (N.F.A.) author access to dataset after successful completion of the required CITI Program training and compliance with the Data Use Agreement (DUA). This datasets are not available publicly due to the sensitive nature of patient data and ethical restrictions under HIPAA. Other researchers can access the dataset after apply through the PhysioNet portal at

https://physionet.org/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nadu, T. An intrusion detection system using a machine learning approach in IOT-based smart cities. J. Internet Serv. Inf. Secur. (JISIS) 2023, 13, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautala, A.J.; Shavazipour, B.; Afsar, B.; Tulppo, M.P.; Miettinen, K. Machine learning models in predicting health care costs in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome: A prospective pilot study. Cardiovasc. Digit. Health J. 2023, 4, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, I.; Mahmood, A.; Razzaq, S.; Jafri, S.H.M.; Aziz, I. IoT applications and challenges in smart cities and services. J. Eng. 2023, 2023, e12262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Shi, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Decentralized identifiers based IoT data trusted collection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahlan, A.; Ranjan, R.P.; Hayes, D. Artificial intelligence innovation in healthcare: Literature review, exploratory analysis, and future research. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, M.A.; Ahmed, M.H.; Seliem, H.; Sheltami, T.R.; Alghamdi, T.M. Smart Health Systems Components, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Can. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 45, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rayash, A.; Dincer, I. Development of integrated sustainability performance indicators for better management of smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, F.H.; Abi Sen, A.A.; Ramazan, M.S.; Alzahrani, B.; Bahbouh, N.M. A Smart Framework for Managing Natural Disasters Based on the IoT and ML. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, A.L.; O’Neill, D.W.; Hickel, J.; Roux, N. The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M. Applications of ML/DL in the management of smart cities and societies based on new trends in information technologies: A systematic literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondschein, J.; Clark-Ginsberg, A.; Kuehn, A. Smart cities as large technological systems: Overcoming organizational challenges in smart cities through collective action. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Hasanefendic, S.; Bossink, B. A systematic literature review of the smart city transformation process: The role and interaction of stakeholders and technology. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 101, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Javidroozi, V. Smart city development: Data sharing vs. data protection legislations. Cities 2024, 148, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, M.H.; Madanipour, M.; Nikravan, M.; Asghari, P.; Mahdipour, E. A systematic review of IoT in healthcare: Applications, techniques, and trends. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 192, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, J. The IoT to Smart Cities-A design science research approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 219, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakar, D.; Sundarrajan, M.; Manikandan, R.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Masud, M.; Alqhatani, A. Energy analysis-based cyber attack detection by IoT with artificial intelligence in a sustainable smart city. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, I.; Shamayleh, A.; Ndiaye, M. Healthcare and the Internet of Medical Things: Applications, Trends, Key Challenges, and Proposed Resolutions. Informatics 2024, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.X.; Xue, Y. Machine learning technique and applications–an classification analysis. J. Mach. Comput. 2021, 1, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.T.; Zia, M.F. Smart city technologies, key components, and its aspects. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 9–10 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.S.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Kumar, A.; Elmaghraby, A. IoT in smart cities: A survey of technologies, practices and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 429–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Nawara, D.; Kashef, R. Connecting the indispensable roles of iot and artificial intelligence in smart cities: A survey. J. Inf. Intell. 2024, 2, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugurullo, F. Urban artificial intelligence: From automation to autonomy in the smart city. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Hassoun, A.; Jagtap, S.; Tetteh-Caesar, M.; Kumar, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Goksen, G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Meat 4.0: Principles and applications of industry 4.0 technologies in the meat industry. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Al-Turjman, F.; Mostarda, L.; Gagliardi, R. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in smart cities. Comput. Commun. 2020, 154, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terence, S.; Purushothaman, G. Systematic review of Internet of Things in smart farming. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2020, 31, e3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Hussain, S.A.; Rust, S.; Huang, Y. Extracting Medical Information From Free-Text and Unstructured Patient-Generated Health Data Using Natural Language Processing Methods: Feasibility Study With Real-world Data. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e43014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, G.; Kubler, S.; Georges, J.P. Innovative blockchain-based farming marketplace and smart contract performance evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Costa, N.; Pereira, A. A systematic review of IoT solutions for smart farming. Sensors 2020, 20, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliappan, V.K.; Gnanamurthy, S.; Yahya, A.; Samikannu, R.; Babar, M.; Qureshi, B.; Koubaa, A. Machine Learning Based Healthcare Service Dissemination Using Social Internet of Things and Cloud Architecture in Smart Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, G. Internet of Medical Things Healthcare for Sustainable Smart Cities: Current Status and Future Prospects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshvarianjahromi, M.; Majumder, S.; Kumar, S.; Naghshvarianjahromi, N.; Deen, M.J. Natural brain-inspired intelligence for screening in healthcare applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67957–67973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Jeon, G.; Piccialli, F. A deep-learning-based smart healthcare system for patient’s discomfort detection at the edge of Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 10318–10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proniewska, K.; Pregowska, A.; Malinowski, K.P. Identification of human vital functions directly relevant to the respiratory system based on the cardiac and acoustic parameters and random forest. IRBM 2021, 42, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Noumeir, R.; Rambaud, J.; Sans, G.; Jouvet, P. Adaptation of Autoencoder for Sparsity Reduction From Clinical Notes Representation Learning. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2023, 11, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Sharma, S.; Tanwar, P.; Dubey, G.; Memoria, M. Improving Health Care Analytics: LSTM Networks for Enhanced Risk Assessment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 259, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, G.; Chauhan, R.; Singh, M.; Singh, D. Pre-emption of affliction severity using HRV measurements from a smart wearable; case-study on SARS-Cov-2 symptoms. Sensors 2020, 20, 7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.R.; Lohani, R.B. Hidden Markov Model energy conservation approach for continuous monitoring of vital signs in geriatric care applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1921, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkan, A.R.M.; Khalil, I. PEACE-Home: Probabilisticestimation of abnormal clinical events using vital sign correlations for reliable home-based monitoring. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2017, 38, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamaileh, M.; Anthony, P.; Charters, S. Agent-Based Trust and Reputation Model in Smart IoT Environments. Technologies 2024, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.A.; Ben-Ari, A. Multiagent AI Systems in Health Care: Envisioning Next-Generation Intelligence. Fed. Pract. 2025, 42, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, D. Collaborative Care: Multi-Agent Systems in Healthcare. Comput. Electron. Med. 2025, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.G.; Amod, A.; Kumar, S. Advancing healthcare automation: Multi-agent system for medical necessity justification. In Proceedings of the 23rd Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing, Bangkok, Thailand, 16 August 2024; pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, C.V.; Takale, D.G.; Galhe, D.S.; Gawali, P.P.; Mahalle, P.N.; Sule, B.; Bhaskare, P.V. Random Forest Algorithm for Real-Time Health Monitoring Throught Iot Data. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2024, 11, 5293–5299. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.L.; Lu, T.C.; Wang, C.H.; Fang, C.C.; Chen, W.J.; Huang, C.H. Trajectories of vital signs and risk of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 800943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, P.; Tekchandani, R. A machine learning-based decision support system for temporal human cognitive state estimation during online education using wearable physiological monitoring devices. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexan, A.I.; Alexan, A.R.; Oniga, S. Real-time machine learning for human activities recognition based on wrist-worn wearable devices. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanar-Gómez, J.; Robles-Camarillo, D.; Trejo-Macotela, F.R.; Díaz-Parra, O. Electronic system to monitoring vital signs in pregnancy through Random Forests. Int. J. Comb. Optim. Probl. Inform. 2021, 12, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Villarroel, M.; Reisner, A.; Clifford, G.; Lehman, L.; Moody, G.; Heldt, T.; Kyaw, T.; Moody, B.; Mark, R. MIMIC-II Clinical Database (Version 2.6.0); RRID:SCR_007345; PhysioNet: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, V. EHR Data [Data Set]; Kaggle: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vipulshahi/ehr-data (accessed on 9 December 2025).

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of methods.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of methods.

Figure 2.

(a) Correlation matrix for HR, RR, ABP, and SpO2. (b) Correlation matrix for HR, RR, SpO2, SBP, and DBP.

Figure 2.

(a) Correlation matrix for HR, RR, ABP, and SpO2. (b) Correlation matrix for HR, RR, SpO2, SBP, and DBP.

Figure 3.

(a) Pair plots for HR, RR, ABP, and SpO2 by HR category. (b) Pair plots for heart rates, respiratory rates, systolic BP, diastolic BP, and oxygen saturation by HR category.

Figure 3.

(a) Pair plots for HR, RR, ABP, and SpO2 by HR category. (b) Pair plots for heart rates, respiratory rates, systolic BP, diastolic BP, and oxygen saturation by HR category.

Figure 4.

PLPF-MAS model diagram.

Figure 4.

PLPF-MAS model diagram.

Figure 5.

Linear Regression Model with Multivariable Architecture.

Figure 5.

Linear Regression Model with Multivariable Architecture.

Figure 6.

Autoencoder model architecture.

Figure 6.

Autoencoder model architecture.

Figure 7.

Hidden Markov model architecture.

Figure 7.

Hidden Markov model architecture.

Figure 8.

Multi-agent system response time.

Figure 8.

Multi-agent system response time.

Figure 9.

Response time of AE-HMM and MAS for individual clinical states.

Figure 9.

Response time of AE-HMM and MAS for individual clinical states.

Table 1.

Summary of previous works.

Table 1.

Summary of previous works.

| Ref. | Method | Aim | Merits | Demerits |

|---|

| [30] | IoMT | Provides continuous monitoring and checks the patient’s health state in smart cities | Continuous monitoring and improved care efficiency | Data privacy, infrastructure costs, and complexity |

| [31] | CDS | Automatically checks human

health conditions (healthy and unhealthy) | Simple and fast | Low accuracy |

| [32] | Mask-RCNN | Classification of movements

associated with normal or abnormal conditions of patients | Speedy responses,

privacy, low costs, and flexibility | Needs powerful computing, is complex, and has difficulty

dealing with noise |

| [33] | SRBDs | Develop, evaluate, and

diagnose the system | Strong classification,

accuracy, low costs, and low hassle | Conducted a preliminary study of clinical data, but only a small sample was used |

| [34] | AE | Enhances the accuracy of medical classification | High classification accuracy | Limited data; lacks applicability |

| [35] | LSTM | Improves the accuracy of risk assessment | High accuracy; supports clinical decision-making | High costs and difficulty with interpretation |

| [36] | HMM | Predicts the onset and worsening

of SARS-CoV-2 infection | Early detection and

non-surgical intervention | Limited data and scope |

| [37] | HMM | Monitoring of vital signs

in elderly patients | Accuracy, adaptability,

reliability, and energy conservation | Limitations, complexity, and

reliance solely on

the accuracy of the data used |

| [38] | HMM, PCA | Predict abnormal

clinical events | High accuracy; analysis

of hidden correlations | Restricted evaluation;

need more cloud resources |

| [39] | Agent-Based Trust | Enhances the security of smart cities | Manages agent trust; reliable interactions | Complexity, slow evaluation, and consumption of resources |

| [40] | MAS | Improves and simplifies the

healthcare system and

supports clinical decisions | High accuracy; more

efficient | Low data accuracy;

high costs |

| [41] | MAS | Prevents IoT medical data

duplication and reduces costs | High flexibility and

scalability | Overhead communication;

complexity |

| [42] | MAS | Uses different large language

models to calculate

the accuracy of performance | High efficiency and

transparency | Complex; agents must be tuned |

Table 2.

Clinical events and their codes.

Table 2.

Clinical events and their codes.

| Clinical Event | Clinical Code |

|---|

| Simultaneous Tachycardia, Hypotension, Tachypnea, and Hypoxia for More than 30 min | THTH |

| Simultaneous Bradycardia, Hypotension, Tachypnea, and Hypoxia for More than 30 min | BHTH |

| Simultaneous Tachycardia, Hypertension, Tachypnea, and Hypoxia for More than 30 min | TTTH |

| Simultaneous Tachycardia, Hypotension, Bradypnea, and Hypoxia for More than 30 min | THBH |

| All Six Bio-Signals Are in the Normal Range | NNNN |

Table 3.

Vital signs and normal values.

Table 3.

Vital signs and normal values.

| Bio-Signal | Normal Range | Vital Sign |

|---|

| Heart rate | 60–100 beats per min | HR |

| Systolic blood pressure | 90–120 mmHg | SBP |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 60–90 mmHg | DBP |

| Arterial blood pressure | 60–110 mmHg | ABP |

| Respiratory rate | 12–18 breaths per min | RR |

| Blood oxygen saturation | 95–100% | SpO2 |

Table 4.

Performance measures of each clinical state using PLPF-MAS and HMM.

Table 4.

Performance measures of each clinical state using PLPF-MAS and HMM.

| Parameter | Method | BHTH | TTTH | THBH | NNNN |

|---|

| Accuracy | HMM | 98.07 | 98.07 | 97.77 | 97.77 |

| PLPF-MAS | 98.22 | 98.32 | 98.05 | 98.01 |

| Precision | HMM | 92.36 | 92.36 | 92.25 | 92.25 |

| PLPF-MAS | 95.09 | 95.25 | 94.95 | 94.85 |

| Sensitivity | HMM | 98.51 | 98.51 | 97.03 | 97.03 |

| PLPF-MAS | 99.15 | 99.15 | 98.27 | 98.36 |

| Specificity | HMM | 97.96 | 97.96 | 97.96 | 97.96 |

| PLPF-MAS | 99.02 | 99.02 | 99.02 | 99.02 |

| F1-Score | HMM | 95.34 | 95.34 | 94.58 | 94.58 |

| PLPF-MAS | 97.01 | 96.32 | 96.05 | 96.07 |

| R2 | HMM | NoN | NoN | NoN | NoN |

| PLPF-MAS | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 |

Table 5.

Performance measures using PLPF-MAS and LSTM.

Table 5.

Performance measures using PLPF-MAS and LSTM.

| Parameters | PLPF-MAS | LSTM |

|---|

| Accuracy | 93% | 87% |

| Precision | 92% | 89% |

| Recall | 94% | 86% |

| F1-Score | 93% | 87% |

| AUC-ROC | 94% | 92% |

| AUC-PR | 89% | 88% |

Table 6.

Multi-agent system simulation results.

Table 6.

Multi-agent system simulation results.

| Index | Test Case | Analyzer Agent

Response Time (s) | Recommendation Agent Response

Time (s) | Clinical Event

Code | Detailed Recommendation |

|---|

| 0 | Normal

Vitals | 0.2922 | 0.2845 | NNNN | Continue routine monitoring; patient’s vital signs are within normal limits |

| 1 | Tachypnea,

Tachycardia,

Hypotension | 0.1468 | 0.1555 | TTTH | Immediately assess airway and breathing; provide oxygen; consider intubation; address tachycardia and hypotension with fluids and vasopressors |

| 2 | Tachycardia,

Hypotension | 0.2724 | 0.1199 | THTH | Administer IV fluids and monitor blood pressure closely; consider vasopressors if hypotension persists |

| 3 | Bradycardia,

Hypotension | 0.1394 | 0.2880 | BHTH | Initiate cardiac pacing or atropine administration; monitor for signs of shock and improve blood pressure |

Table 7.

Comparison of PLPF-MAS, HMM, and LSTM results and features.

Table 7.

Comparison of PLPF-MAS, HMM, and LSTM results and features.

| Features | PLPF-MAS | HMM-PCA | LSTM |

|---|

| Number of bio signals | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Vital signs | HR, BP, RR, SPO2 | HR, BP, RR, SPO2 | HR, BP, RR, SPO2 |

| Clinical event | ANY | ANY | ANY |

| Number of normal samples | 460 in MIMIC-II

1309 in EHR | 700 in MIMIC-II

Not measured | Not measured

13,535 in EHR |

| Number of abnormal samples | 1960 in MIMIC-II

14,001 in EHR | 1720 in MIMIC-II

Not measured | Not measured

1775 in EHR |

| Accuracy | 98.4% in MIMIC-II

93% in EHR | 97.7% in MIMIC-II

Not measured | Not measured

87% in EHR |

| Early prediction capability | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Continuous monitoring support | Yes | Yes | No |

| Response time | Yes | No | No |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |