Predicting Demand in Supply Chain Management: A Decision Support System Using Graph Convolutional Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Current Demand Forecasting Methods

3.2. The Decision-Making Process

- Determination of the need for a decision: Identify and define a situation that requires action, understanding its causes.

- Identification of the criteria: Detail the problem, analyze and validate solutions.

- Assigning weight to each criterion: Evaluate alternatives considering relevant factors and the importance of each criterion.

- Development of possible alternatives: Search for and assess solutions that represent specific values for the decision variables.

- Evaluation of solution alternatives: Integrate data, information, and experience to evaluate options, acknowledging the presence of uncertainty.

- Selection of the optimal solution: Consider quality, risk, and context to choose the best solution.

- Maintain an efficient flow of information to achieve optimal business results.

- Promote effective communication to keep everyone informed about decisions and changes.

- Implement the appropriate technical infrastructure to ensure the proper functioning of the DSS.

- Consider organizational culture to address resistance to change and ensure system adoption.

- Establish adequate planning and a clear organizational strategy to support the integration of information within the company.

Typology of Decisions

3.3. Decision Support System

3.3.1. Data Required for Measurement and Analysis

3.3.2. Measures to Monitor Success

4. Development of the Decision Support System

4.1. Methodology for Decision-Making in Demand Forecasting

- Identifying the need for forecasting. The process begins by recognizing the strategic importance of anticipating demand fluctuations. This step ensures that forecasting efforts are aligned with organizational goals and decision-making needs.

- Definition of forecasting criteria establish clear criteria for forecasting, including relevant time horizons, granularity, and performance metrics. These criteria guide the selection of models and evaluation frameworks.

- Definition of exogenous factors affecting demand. Identify external variables such as macroeconomic indicators, seasonality, competitive actions, and policy changes that influence demand. These factors form the basis for scenario construction.

- Evaluation of the impact of each factor. Assess the relative influence of each exogenous variable on demand through statistical analysis or expert weighting. This enables the development of scenario-based models that reflect diverse market conditions.

- Evaluation of results analyze forecasting outputs across scenarios to quantify sensitivities, validate model performance, and identify potential risks. This step supports strategic planning and risk mitigation.

- Monitoring and adjusting. Continuously track market signals and model accuracy. Real-time adjustments are made to ensure responsiveness to changing conditions and to refine forecasting assumptions.

- Dashboard update, scenario suggestions, and analysis integrate results into decision-support dashboards. Provide updated scenarios and analytical insights to inform strategic actions and foster iterative improvement in forecasting accuracy and resilience.

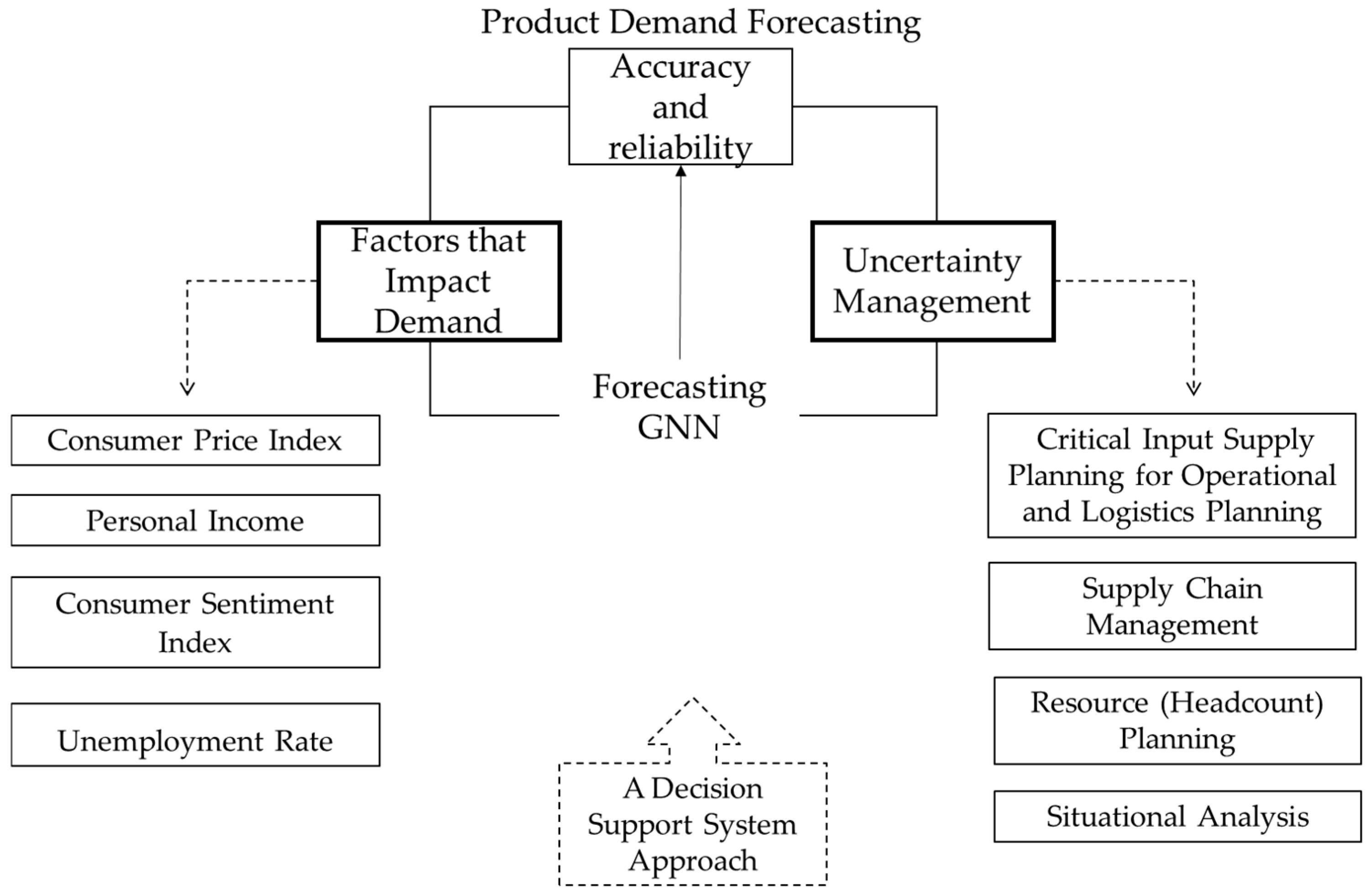

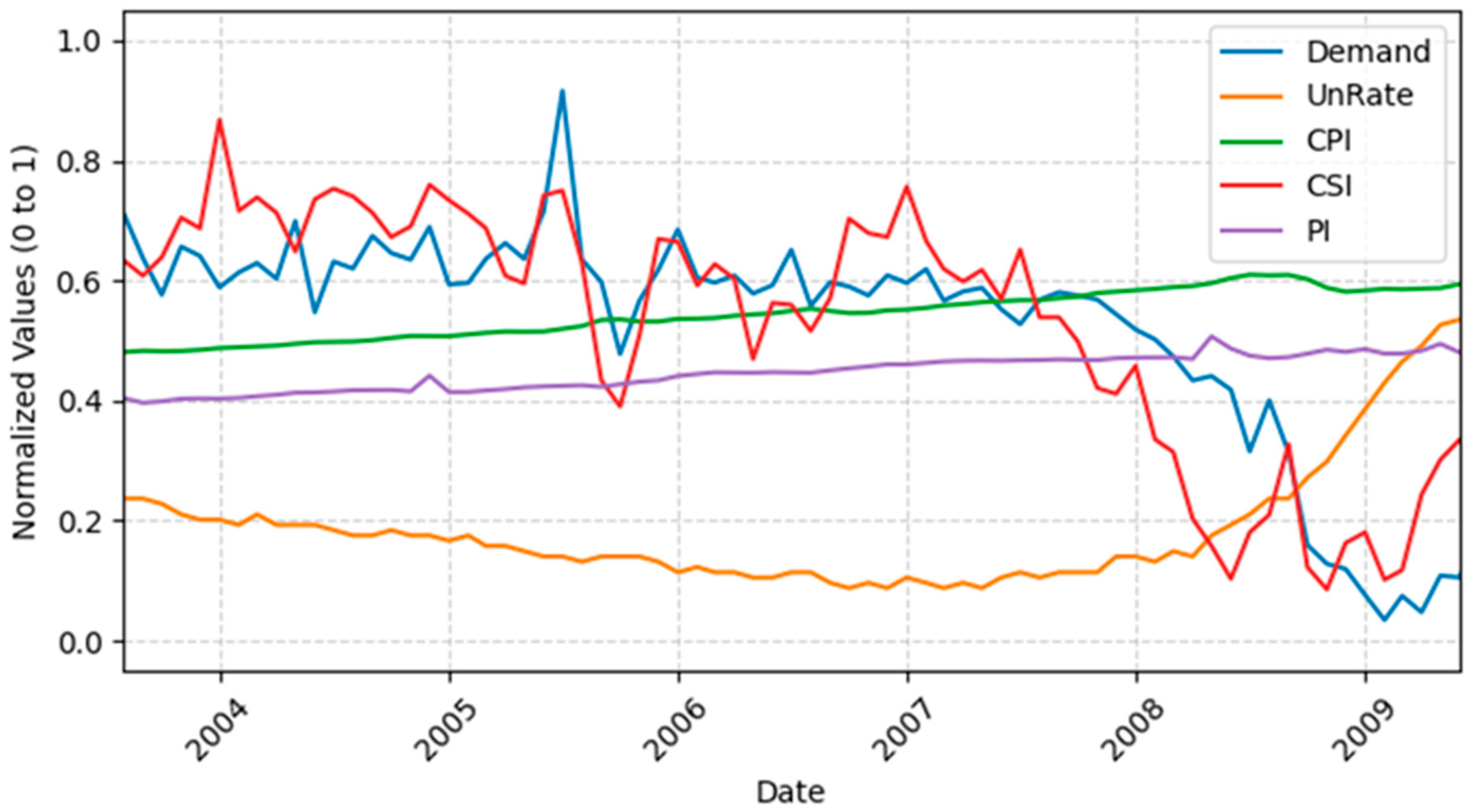

4.2. Factors That Impact Demand

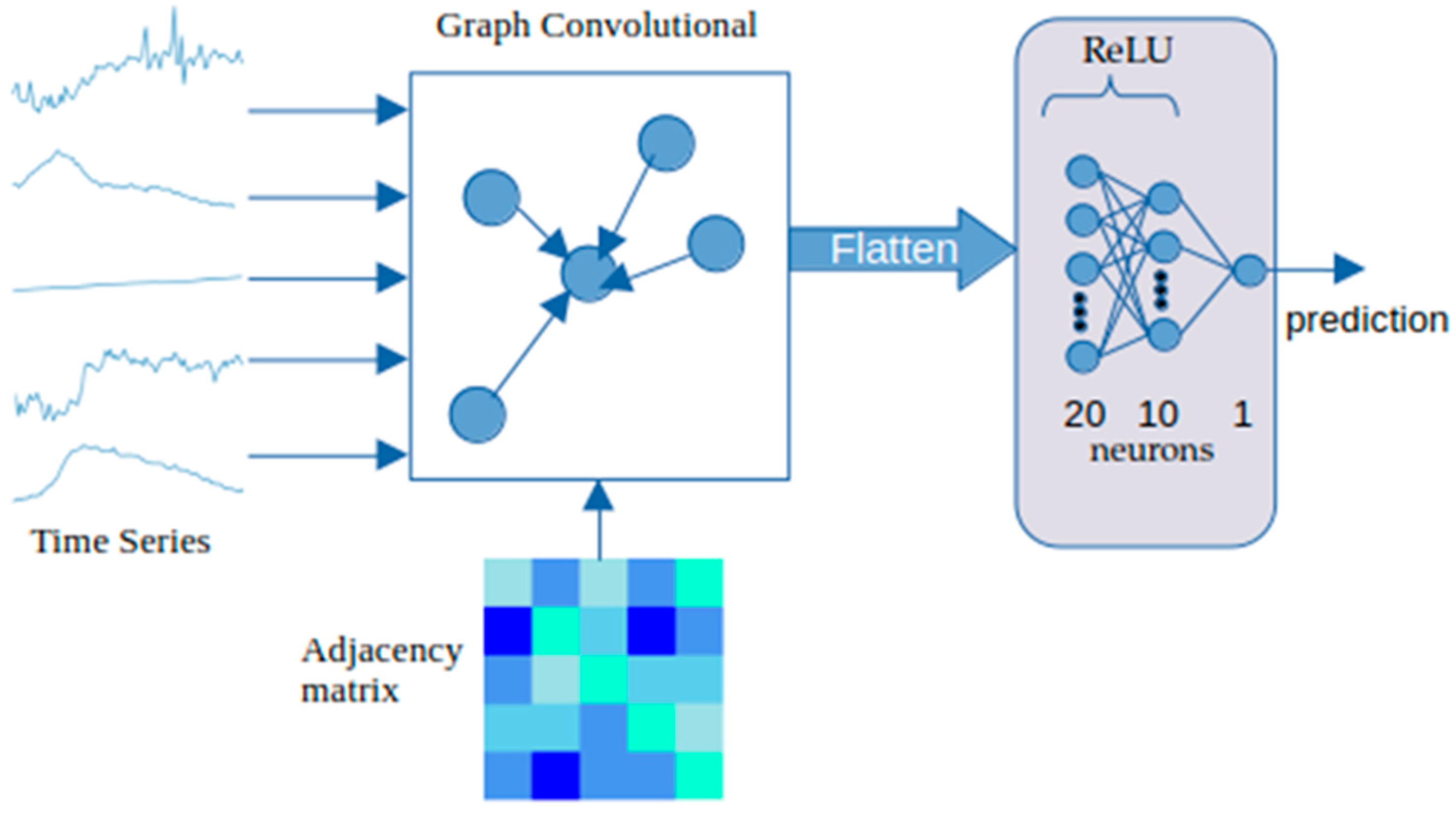

Demand Forecasting

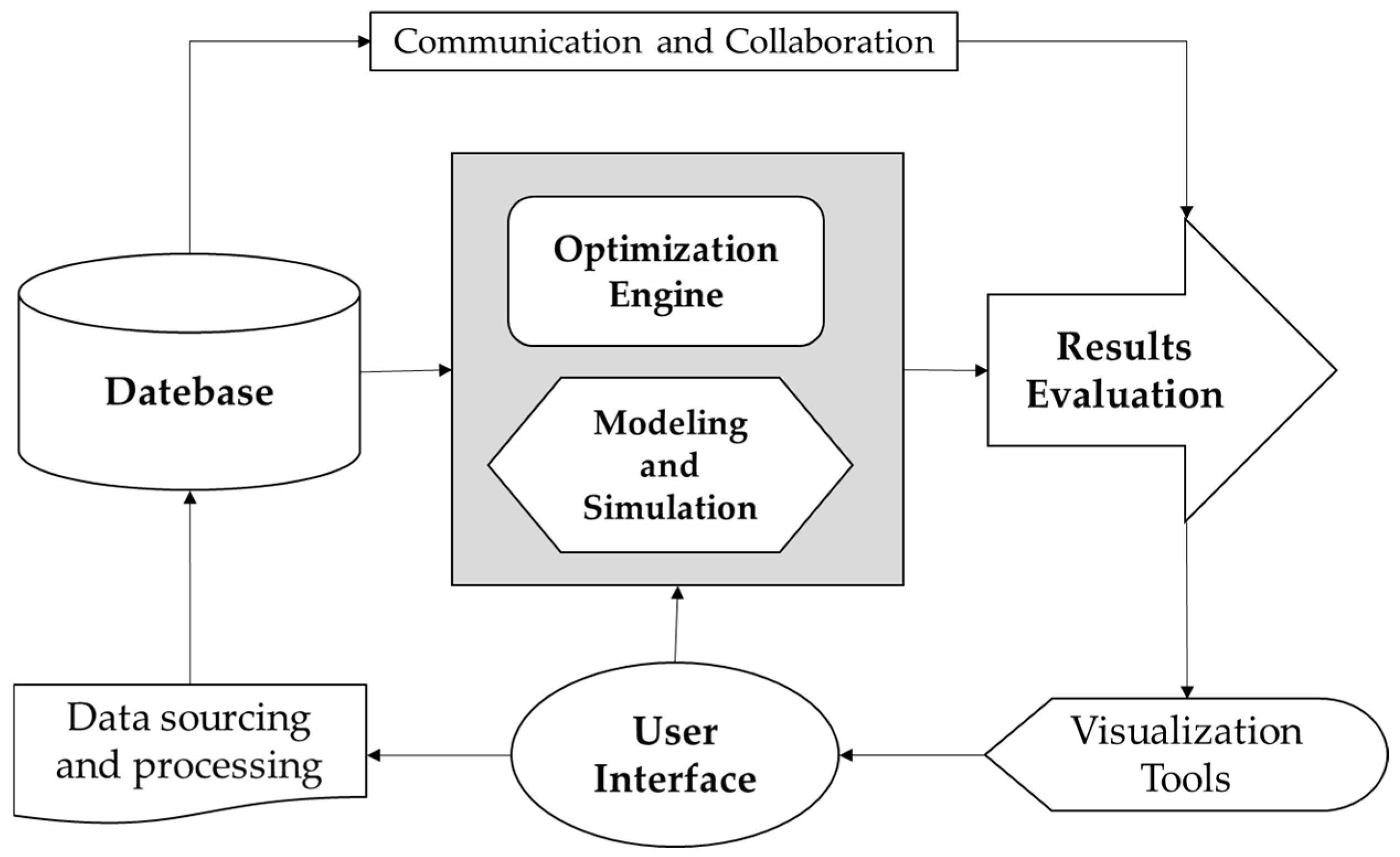

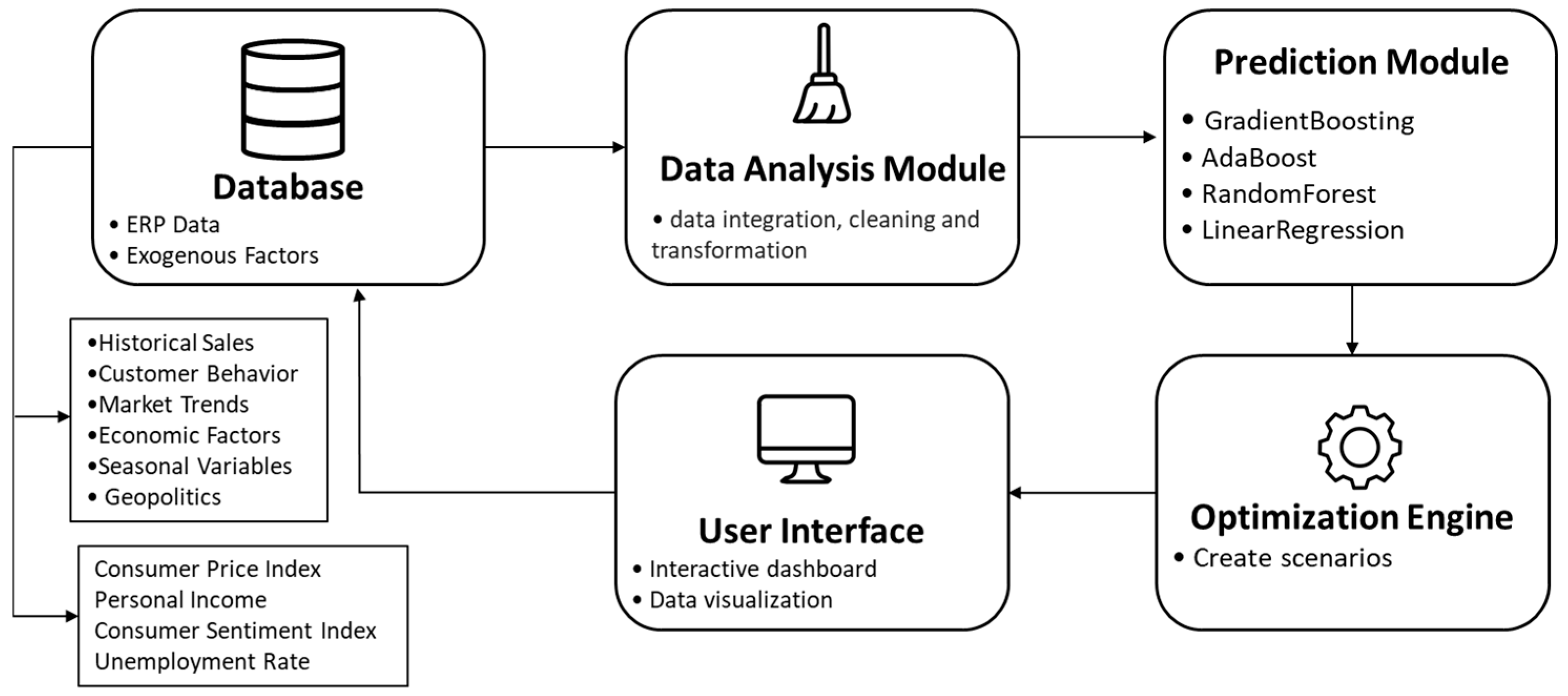

4.3. Decision Support System Components for Demand Forecasting

- Intuitive User Interface: a user-friendly and visually clear interface is required to facilitate interaction and ensure users can easily understand the results.

- Database: this represents the data repository used within the system. It stores and organizes the relevant information needed for the decision-making process. The database may be relational or multidimensional depending on system requirements. It contains historical and current data, as well as the parameters necessary for analysis and decision generation.

- Data Analysis Modules: these modules enable data integration, cleaning, and transformation, as well as the identification of relevant patterns and trends. They may include regression models, time-series analyses, simulations, and others.

- Prediction module: in this study, we evaluate the following algorithms: Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost, Random Forest, and Linear Regression. These Machine Learning algorithms (prediction module) are used to build predictive models based on historical data and relevant external variables.

- Optimization Engine (decision-making module): responsible for generating recommendations and optimal scenarios based on analytical results and organizational objectives.

4.4. Integration Flow Between GNN and DSS

- The GNN processes the item relationship graph and temporal covariates to generate a point forecast for each item.

- Each forecast replaces the previous demand estimate in the DSS’s inventory model.

- The optimization engine recomputes safety stock (SS) using a standard formula: . Where is the historical standard deviation of demand or of past forecast errors for that item, and k is a service-level factor.

- The reorder point (ROP) is updated as: .where , the expected demand during the lead time, is the GNN forecast aggregated over the supplier lead time.

- If the newly computed safety stock or reorder point differs from the current policy by more than a predefined threshold, e.g., ±10%, the DSS triggers a specific, actionable recommendation for example “Increase safety stock for Item X from 20 to 25 units”.

- The user can review, simulate the financial or service-level impact, or approve the recommendation; outcomes are logged to support future model refinement.

5. Results

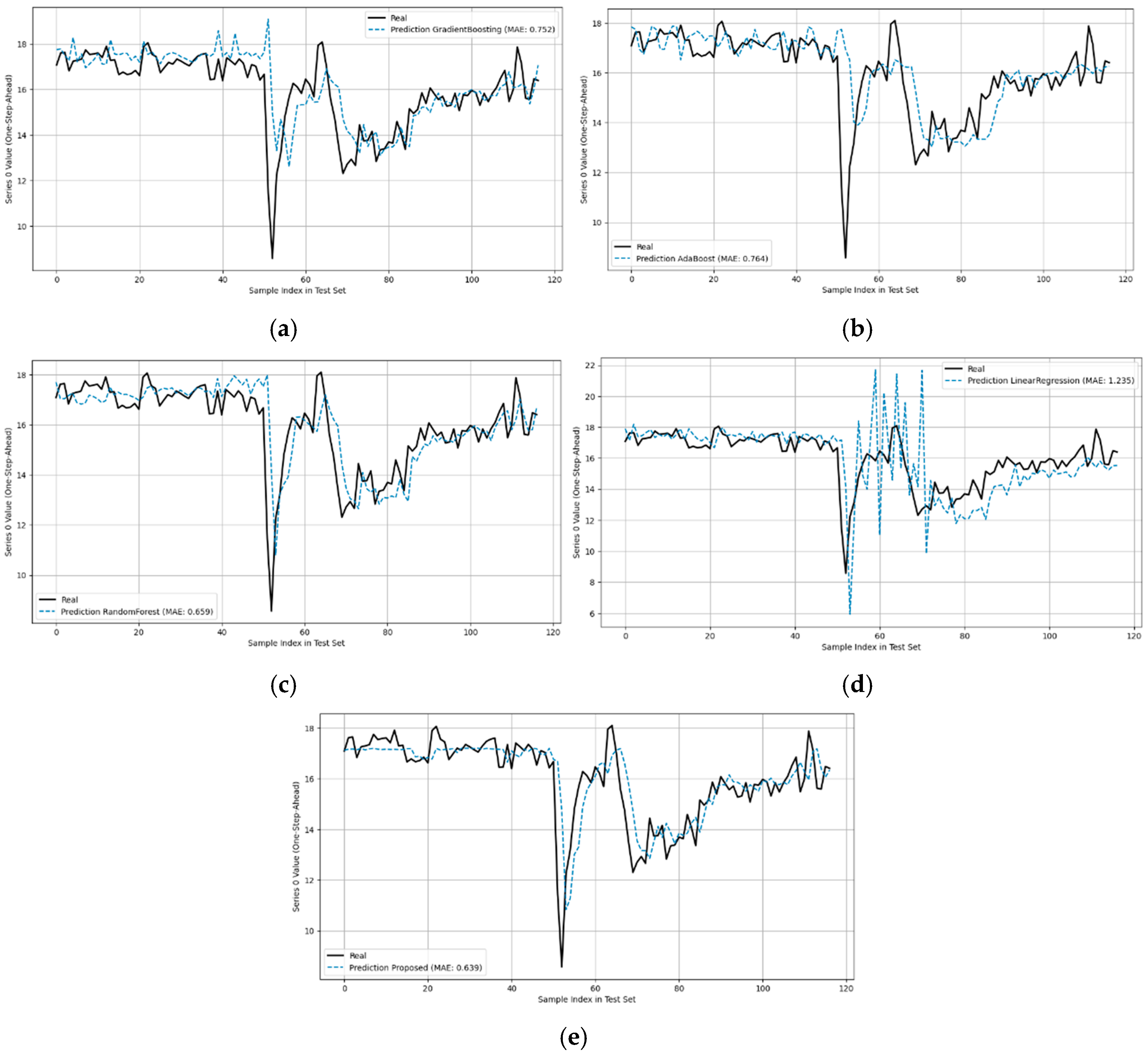

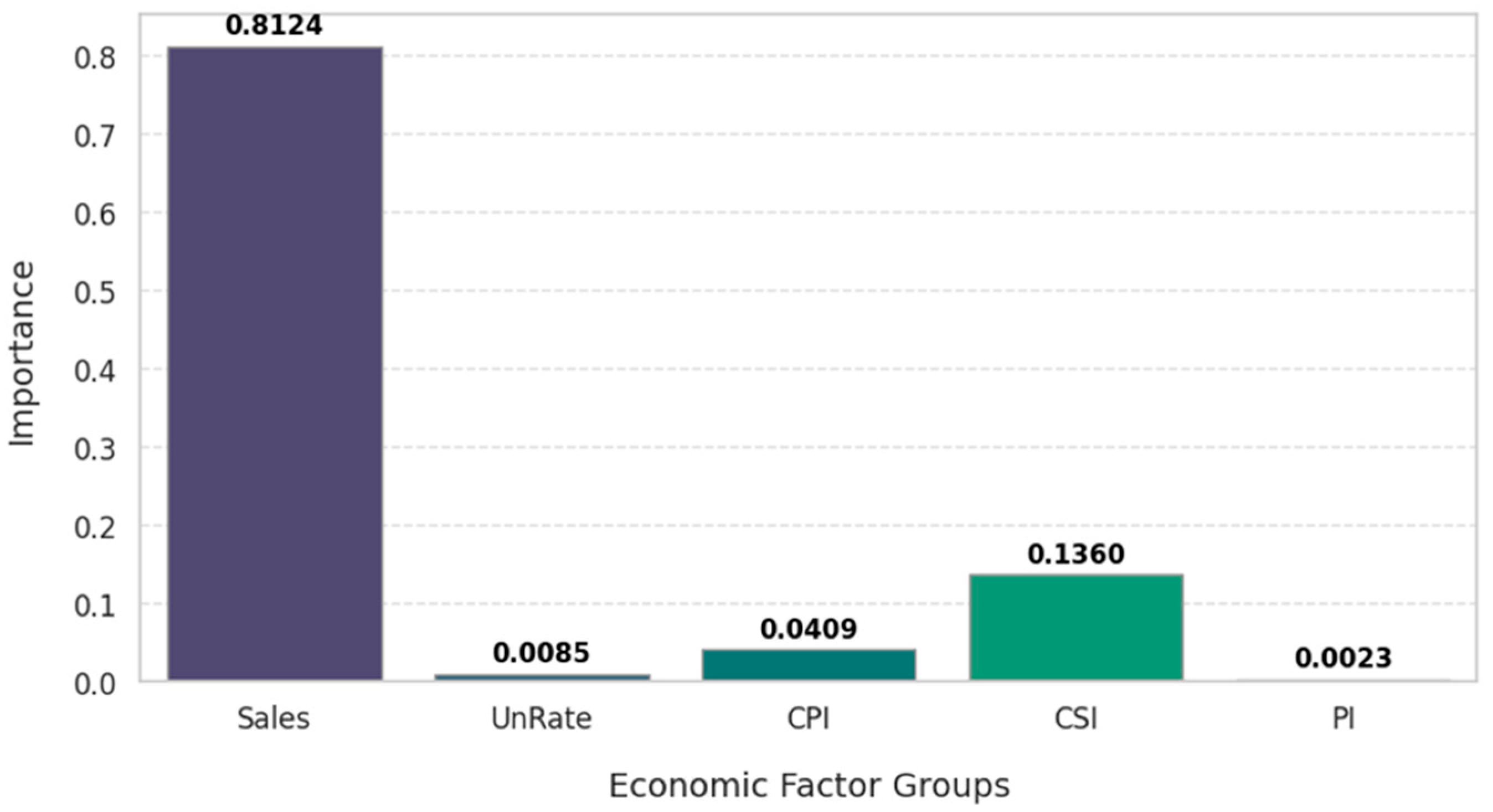

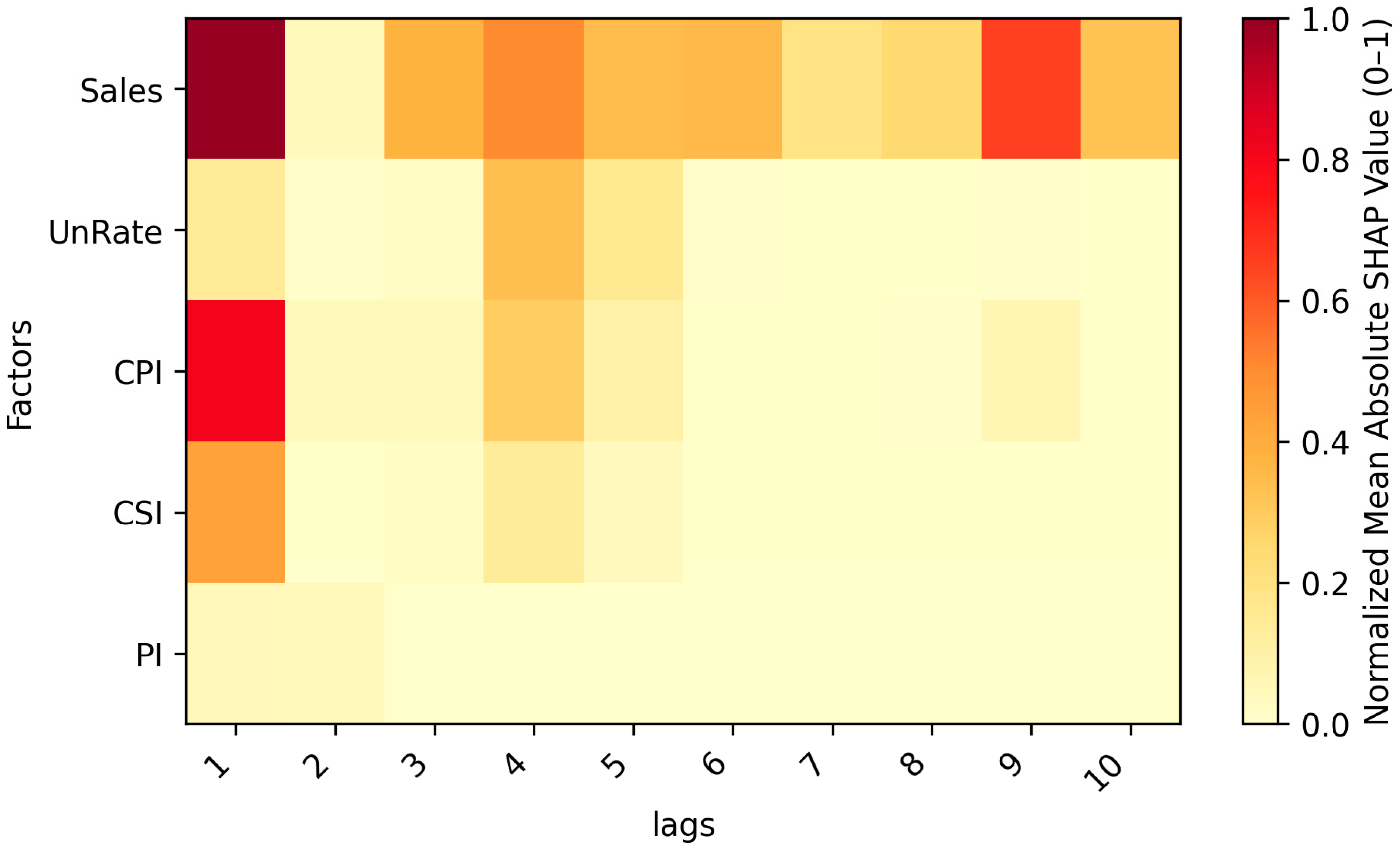

5.1. Results of Demand Forecasting

5.2. Managerial Implications of Demand Forecasting with a Proposed DSS

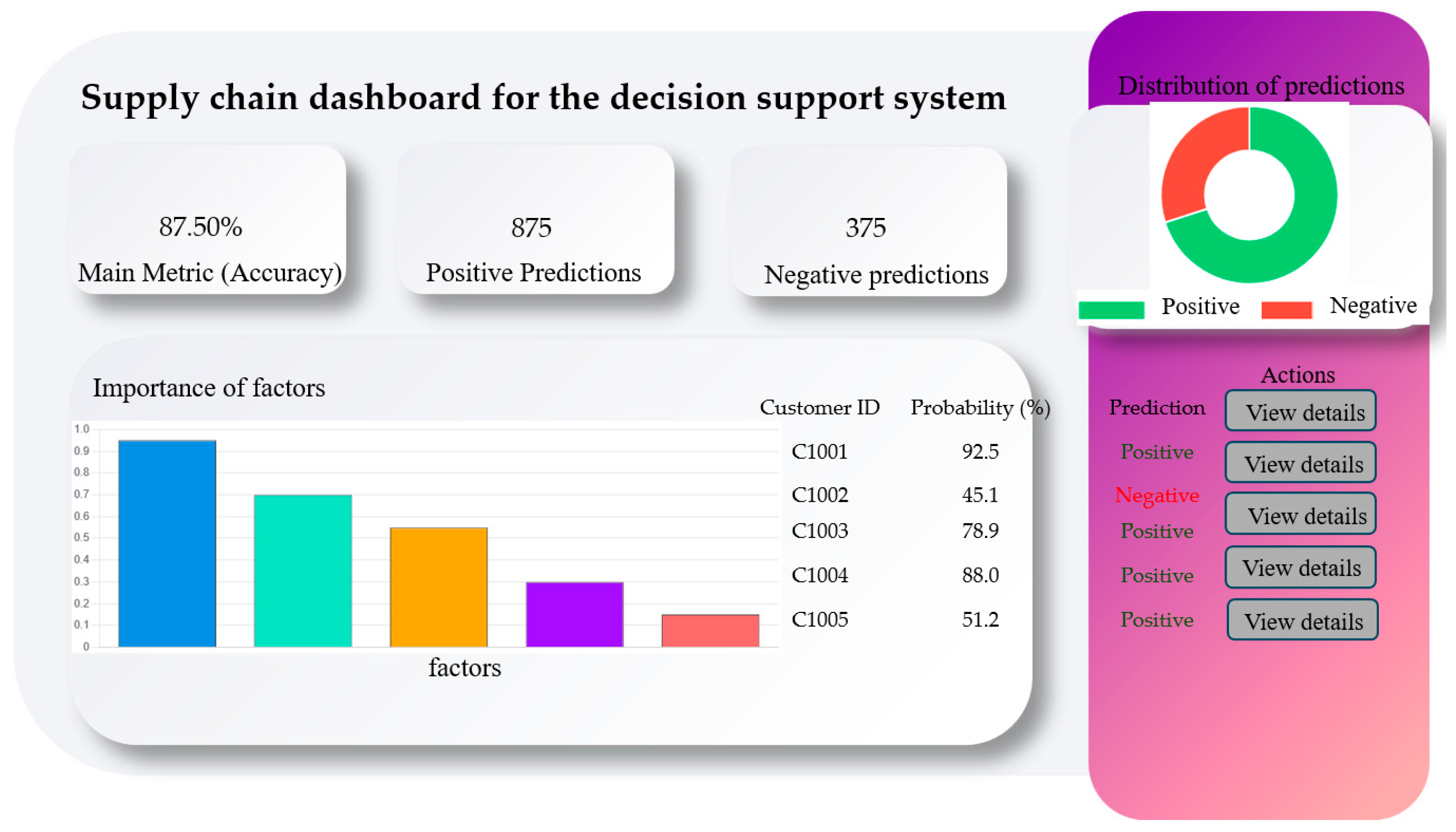

5.3. Scenario Visualization in the DSS: Conceptual Dashboard

- Model performance metrics: overall accuracy, number of positive predictions, and number of negative predictions.

- Importance of external factors: a bar chart showing the relevance of variables such as CSI, CPI, PI, and UnRate in demand prediction.

- Prediction distribution: a donut chart that displays the proportion of positive and negative decisions.

- Customer-level probability table: segmentation of decisions by customer ID and associated probability level.

- Action buttons: allow users to simulate decisions such as increasing production, adjusting inventory, or reviewing critical customers.

- Optimistic scenario: an increase in the CSI input is introduced to the trained GNN, resulting in higher predicted demand and triggering recommendations to ramp up production.

- Pessimistic scenario: a decrease in the CSI input leads the model to forecast lower demand, suggesting production slowdown and tighter inventory control.

- Baseline scenario: original input values are maintained, providing a reference forecast against which deviations in alternative scenarios can be compared.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSS | Decision Support System |

| GNN | Graph Neural Networks |

| CSI | Consumer Sentiment Index |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| PI | Personal Income |

| UnRate | Unemployment Rate |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

References

- Seyedan, M.; Mafakheri, F. Predictive big data analytics for supply chain demand forecasting: Methods, applications, and research opportunities. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.N.C.; Cortez, P.; Carvalho, M.S.; Frazão, N.M. A multivariate approach for multi-step demand forecasting in assembly industries: Empirical evidence from an automotive supply chain. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 142, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.; Ahmed, W. A Comprehensive Analysis of Demand Prediction Models in Supply Chain Management. AJIBM 2023, 13, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadayonrad, Y.; Ndiaye, A.B. A new key performance indicator model for demand forecasting in inventory management considering supply chain reliability and seasonality. Supply Chain Anal. 2023, 3, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahmani, E.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K. Demand Forecasting in Supply Chain Using Uni-Regression Deep Approximate Forecasting Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-292-41619-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano-Ponce, A.; Zaldumbide-Peralvo, D. Disponibilidad de inventarios frente a la demanda en productos de Tiendas TuTi. 593 Digit. Publ. CEIT 2024, 9, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox-Palafox, D.; Medina-Marín, J.; Seck-Tuoh-Mora, J.C.; Serna-Díaz, M.G.; Hernández-Romero, N. Modelo de pronóstico de cadena de suministro mediante redes neuronales. Pädi Boletín Científico De Cienc. Básicas E Ing. Del ICBI 2023, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle García, J.S.; Pincay Delgado, M.A.; Mendoza Pionce, B.S.; Bravo Quijije, G.S. USO ESTRATÉGICO DE LA INTELIGENCIA ARTIFICIAL EN LA GESTIÓN DE LA CADENA DE SUMINISTRO EMPRESARIAL. Cien. Y Des. 2024, 27, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, J.; Riascos-Guerrero, J.A.; Galván-Colonia, E.; Pincay-Lozada, J.L. Estrategias basadas en inteligencia artificial para la gestión de inventarios en la cadena de suministro. Rev. Tecnol. En Marcha 2024, ág, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teniwut, W.A.; Hasyim, C.L. Decision support system in supply chain: A systematic literature review. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 8, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron Fonseca, B.; Mar Cornelio, O. Sistemas De Recomendación Para La Toma De Decisiones. ESTADO Del Arte: Sistemas De Recomendación Para La Toma De Decisiones. UNESUM-Cienc. 2022, 6, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeeva, Z.; Kovriga, S.; Fedko, E. DSS-Tool for Demand Planning: An Example of Automotive Industry. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 21st Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Moscow, Russia, 15–17 July 2019; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, G.; Silva, F.; Ferraz, F.; Silva, A.; Analide, C.; Novais, P. Developing an ambient intelligent-based decision support system for production and control planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications, Porto, Portugal, 16–18 December 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 984–994. [Google Scholar]

- Fadda, E.; Perboli, G.; Rosano, M.; Mascolo, J.E.; Masera, D. A Decision Support System for Supporting Strategic Production Allocation in the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.R.; Burggräf, P.; Steinberg, F. A systematic review of machine learning for hybrid intelligence in production management. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 15, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, D.; Corso, L.L. Aplicação de Inteligência Artificial e Modelos Matemáticos para Previsão de Demanda em uma indústria do ramo plástico. Sci. Cum Ind. 2020, 8, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilimci, Z.H.; Akyuz, A.O.; Uysal, M.; Akyokus, S.; Uysal, M.O.; Atak Bulbul, B.; Ekmis, M.A. An Improved Demand Forecasting Model Using Deep Learning Approach and Proposed Decision Integration Strategy for Supply Chain. Complexity 2019, 2019, 9067367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-S.; Chen, Y.-J. Optimizing Supply Chain Networks with the Power of Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Zhang, H.; Yan, X.; Miao, Q. Intricate Supply Chain Demand Forecasting Based on Graph Convolution Network. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rossi, R.A.; Mahadik, K.; Eldardiry, H. A Context Integrated Relational Spatio-Temporal Model for Demand and Supply Forecasting. arXiv 2020. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Context-Integrated-Relational-Spatio-Temporal-for-Chen-Rossi/82a9072ef6cf2209fc1216e635eca93d11e253e7 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Cini, A.; Marisca, I.; Bianchi, F.M.; Alippi, C. Scalable Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, A.O. Leveraging Data Science for Demand Forecasting and Inventory Management: A Comprehensive Review. J. Basic Appl. Res. Int. 2025, 31, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.S. Retail Demand Forecasting Using Neural Networks and Macroeconomic Variables. JMSS 2023, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraete, G.; Aghezzaf, E.-H.; Desmet, B. A leading macroeconomic indicators’ based framework to automatically generate tactical sales forecasts. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaert, Y.R.; Aghezzaf, E.-H.; Kourentzes, N.; Desmet, B. Tactical sales forecasting using a very large set of macroeconomic indicators. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veena, S.; Aravindhar, J. Challenges of Machine Learning Algorithms Used in Business for Decision-Making; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA; p. 5066812. [CrossRef]

- Laudon, K.C.; Laudon, K.; Laudon, J.P.; Traver, C.G. Essentials of Management Information Systems; Pearson: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-292-45036-0. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Wren, G.; Daly, M.; Burstein, F. Reconciling business intelligence, analytics and decision support systems: More data, deeper insight. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 146, 113560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, D.H.; Jamjoom, A.A. Decision support system for handling control decisions and decision-maker related to supply chain. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukhay, F.; Zaraté, P.; Romdhane, T. Intelligent Decision Support System for Updating Control Plans. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.L.; Olivei, G.P. The Forecasting Power of Consumer Attitudes for Consumer Spending. Working Papers, Working Paper 14-10. 2014. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/109703 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Nguyen, T.N.; Haider, M.; Jisan, A.H.; Raju, M.A.H.; Imam, T.; Khan, M.M.; Jafar, A.E. Product Demand Forecasting with Neural Networks and Macroeconomic Indicators: A Comparative Study among Product Categories. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2024, 6, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douaioui, K.; Oucheikh, R.; Benmoussa, O.; Mabrouki, C. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Demand Forecasting in Supply Chain Management: A Critical Review. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Lepenioti, K.; Apostolou, D.; Mentzas, G. A Review of Data-Driven Decision-Making Methods for Industry 4.0 Maintenance Applications. Electronics 2021, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Tiwari, A.; Saha, S.; Ghimire, A.; Imran, M.A.U.; Khatoon, R. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in Information Technology System to Evaluate the Adoption of Decision Support System. J. Comput. Commun. 2024, 12, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Light Weight Vehicle Sales: Autos and Light Trucks [ALTSALES], Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ALTSALES (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL], 582 Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real Disposable Personal Income [DSPIC96], Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of 584 St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DSPIC96 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- University of Michigan: Consumer Sentiment [UMCSENT], Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank 587 of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UMCSENT (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jahin, M.A.; Shahriar, A.; Amin, M.A. MCDFN: Supply chain demand forecasting via an explainable multi-channel data fusion network model. Evol. Intell. 2025, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadov, Y.; Helo, P. Deep learning-based approach for forecasting intermittent online sales. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2023, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Machine Learning for Demand Forecasting in Supply Chain Optimization. preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demand | UnRate | CPI | CSI | PIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 14.834182 | 6.081176 | 176.637025 | 84.458992 | 1.03 × 104 |

| std. dev. | 2.154392 | 1.760198 | 68.564177 | 13.255458 | 3.93 × 103 |

| minimum | 8.571 | 3.4 | 55.9 | 50 | 4.65 × 103 |

| maximum | 21.709 | 14.8 | 323.364 | 112 | 2.05 × 104 |

| variance | 4.641404 | 3.098298 | 4701.046356 | 175.707171 | 1.54 × 107 |

| range | 13.138 | 11.4 | 267.464 | 62 | 1.59 × 104 |

| Model | MSE | MAE | R2 | MASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GradientBoosting | 1.617565 | 0.752316 | 0.404102 | 1.178886 |

| AdaBoost | 1.777216 | 0.764485 | 0.345288 | 1.197955 |

| RandomForest | 1.207063 | 0.659251 | 0.555328 | 1.033053 |

| LinearRegression | 3.738526 | 1.234706 | −0.377243 | 1.934796 |

| Proposed | 1.158725 | 0.638634 | 0.573135 | 1.000745 |

| Sample Error | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | = 5.2 | = 2.9 | = 3.7 | = 2.3 |

| GradientBoosting | 7.7 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 2.5 |

| AdaBoost | 6.3 | 8.4 | 4.3 | 2.0 |

| RandomForest | 6.5 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| LinearRegression | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 3.4 |

| Proposed | 5.2 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sifuentes-Domínguez, S.; Mejia-Muñoz, J.-M.; Cruz-Mejia, O.; Pizarro-Gurrola, R.; Domínguez-Flores, A.-S.; Ortega-Máynez, L. Predicting Demand in Supply Chain Management: A Decision Support System Using Graph Convolutional Networks. Future Internet 2026, 18, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010026

Sifuentes-Domínguez S, Mejia-Muñoz J-M, Cruz-Mejia O, Pizarro-Gurrola R, Domínguez-Flores A-S, Ortega-Máynez L. Predicting Demand in Supply Chain Management: A Decision Support System Using Graph Convolutional Networks. Future Internet. 2026; 18(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleSifuentes-Domínguez, Stefani, Jose-Manuel Mejia-Muñoz, Oliverio Cruz-Mejia, Rubén Pizarro-Gurrola, Aracelí-Soledad Domínguez-Flores, and Leticia Ortega-Máynez. 2026. "Predicting Demand in Supply Chain Management: A Decision Support System Using Graph Convolutional Networks" Future Internet 18, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010026

APA StyleSifuentes-Domínguez, S., Mejia-Muñoz, J.-M., Cruz-Mejia, O., Pizarro-Gurrola, R., Domínguez-Flores, A.-S., & Ortega-Máynez, L. (2026). Predicting Demand in Supply Chain Management: A Decision Support System Using Graph Convolutional Networks. Future Internet, 18(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010026