EsCorpiusBias: The Contextual Annotation and Transformer-Based Detection of Racism and Sexism in Spanish Dialogue

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel context-aware corpus: We release EsCorpiusBias, the first large Spanish dataset of annotated multi-turn, multi-user forum dialogues for sexism and racism detection. Unlike many previous datasets in Spanish that focus on isolated Twitter comments or decontextualized comment fragments, our approach focuses on contextual grounding, recognizing that toxicity often arises from discursive interaction.

- Rich contextual annotation protocol: Three-turn dialogues were annotated following meticulously developed guidelines that covered both explicit and implicit manifestations of sexism and racism.

- Reliable annotation quality: Annotations were conducted following a well-defined protocol using the Prodigy tool, resulting in moderate to substantial inter-annotator agreement (Cohen’s Kappa: 0.55 for sexism and 0.79 for racism). Discrepancies were resolved using a manual adjudication protocol.

- Comprehensive model evaluation: We trained and evaluated models such as logistic regression, SpaCy’s n-gram bag-of-words model (TextCatBOW) and the BETO transformer-based model. Our experiments show that contextualized transformer-based approaches (BETO) significantly outperform baseline models (such as logistic regression and TextCatBOW). Better recall and F1 score performance were observed for the contextualized variants of our models, underscoring the critical role of the preceding dialog context. Comparison with external models (such as piuba-bigdata/beto-contextualized-hate-speech and unitary/multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta from Hugging Face) without domain-specific fine-tuning confirmed their shortcomings, especially in recall, highlighting the need to tune the models specifically for the linguistic characteristics and nuances of forum dialogues.

- Error and lexical bias analysis: We provide confusion matrices, error examples, and lexical overlap analysis, revealing current model strengths and limitations in detecting implicit bias.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Collection Procedures

- Removal of URLs, email addresses, and phone numbers.

- Discarding of comments shorter than 10 characters.

- Anonymization of usernames and user mentions.

- Application of a basic profanity filter adapted from [60] to exclude overtly toxic language not relevant for initial model training.

3.2. Annotation Framework and Theoretical Foundations

3.2.1. Annotation of Sexism

- Hostile sexism: Openly negative or demeaning attitudes towards women. Example: “Women don’t belong in the workplace; they should stay at home”.

- Benevolent sexism: Seemingly positive but patronizing beliefs that reinforce traditional roles. Example: “Women are delicate, the angel in the house”.

- Objectification: Reducing women to sexual objects or physical appearance, ignoring their dignity. Example: “Women exist solely for our enjoyment”.

- Ideology and inequality: Comments discrediting feminism, denying gender inequality, or portraying men as victims of gender-based oppression.

- Stereotyping and domination: False beliefs suggesting women are naturally suited for certain roles or unfit for others, reinforcing male superiority.

- Sexual violence: Comments suggesting, soliciting, or implying sexual aggression or harassment.

- Misogyny and non-sexual violence: Explicit expressions of hatred or non-sexual violence towards women.

- Read the entire dialogue for overall context and dynamics.

- Evaluate the targeted comment based on sexism definitions and examples.

- Annotate the target comment within the context of the dialogue using a binary classification framework: sexist/non-sexist.

3.2.2. Annotation of Racism/Xenophobia

- Affect: Negative emotions and reactions, particularly those expressing hate or anger based on racial, ethnic, or religious differences. Example: “Take your damn piece of pizza and go back to Africa”.

- Evaluation: Negative judgments regarding inherent characteristics attributed to specific groups, used dogmatically as reasons for discrimination. Example: “These people aren’t even citizens of this country”.

- Judgment: Negative assessments about behaviors and actions perceived as typical or representative of specific racial, ethnic, or religious groups. Example: “Crime, welfare, immigration—these issues always involve the Black, Hispanic, or Asian communities”.

- Overt racism/aggression: Direct, explicit expressions of racial or ethnic prejudice, including derogatory terms, negative stereotypes, and calls for discrimination or violence. Example: “Immigrants don’t adopt our values”.

- Covert racism/aggression: Subtle or superficially neutral comments containing implicit racial prejudices or assumptions, often questioning someone’s belonging or origins. Example: “You don’t look Spanish,” or “Where are your parents really from?”

- Stereotypes: Comments or humor reinforcing stereotypical views. Example: “All Asians are good at math,” or compliments based on stereotypes: “You speak Spanish really well for someone from…”

- Environmental racism: Statements implicitly accepting racial inequalities in housing, employment, or service accessibility, often justified through meritocratic rhetoric. Example: “People are in their situations through their own efforts; we don’t need policies to balance racial inequalities”.

- Read the entire dialogue carefully to comprehend the overall context and interactions.

- Evaluate whether the targeted comment aligns with the predefined categories of racial bias and xenophobia.

- Annotate the target comment within a dialogue context using a binary classification framework: xenophobic/racist or non-xenophobic/non-racist.

3.2.3. Annotation of Homophobia

3.2.4. Annotation of Aporophobia

- generalizations associating poverty with personal failure or criminality;

- expressions of disgust or inferiority toward poor individuals;

- denial of structural causes of poverty, often replaced by narratives of meritocracy;

- language that dehumanizes or blames the poor for systemic issues.

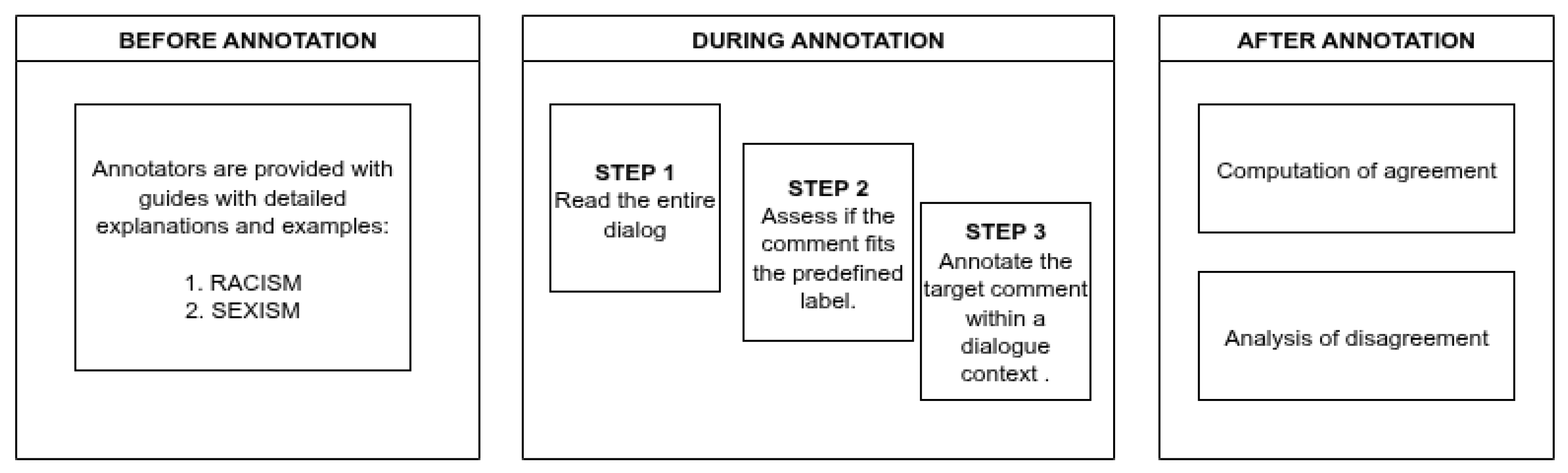

3.3. Annotation Procedure and Contextual Grounding in Dialogue

3.4. Models and Experimental Set-Up

- Single-turn: Trained on individual comments without dialogue context, thus evaluating the model’s ability to detect hate speech solely based on isolated utterances.

- Contextualized: Incorporating preceding dialogue turns to provide context, this model addressed the conversational nature of online interactions, capturing discursive nuances critical for accurate classification.

- Logistic regression baseline: A traditional logistic regression model trained on TF-IDF vectorized text features served as an interpretable baseline, helping to ascertain whether simpler linear methods could effectively capture the linguistic features indicative of sexist and racist content.

- SpaCy TextCatBOW pipeline: As a lightweight neural baseline, we fine-tuned SpaCy’s TextCatBOW architecture, which employs bag-of-words hash embeddings pooled via mean aggregation and fed into a single-layer feedforward classifier. Optimized with Adam and early stopping, this transformer-free model offers high inference speed and serves as a useful benchmark for isolating the impact of contextual embeddings.

- Transformer-based Pipeline (SpaCy + BETO): To leverage advanced contextual embeddings, we implemented and fine-tuned a transformer-based model utilizing SpaCy’s transformer integration. The configuration incorporated the widely recognized BETO model (dccuchile/bert-base-spanish-wwm-cased, https://huggingface.co/dccuchile/bert-base-spanish-wwm-cased, (accessed on 16 June 2025)), specifically configured as follows (see Appendix A for more details):

- -

- Used the SpaCy pipeline component transformer combined with a textcat_multilabel classifier.

- -

- Implemented subtoken pooling strategies (mean pooling) and strided windows of 128 tokens with a stride of 224 tokens, ensuring comprehensive coverage of long conversational texts.

- -

- Fine-tuned with the Adam optimizer (learning rate of , dropout of 0.1), trained for up to 20 epochs or until convergence.

- piuba-bigdata/beto-contextualized-hate-speech, https://huggingface.co/piuba-bigdata/beto-contextualized-hate-speech, (accessed on 16 June 2025) [12]: This BETO-based transformer model, originally fine-tuned on Spanish news comment sections, provided insights into model performance when applied to conversational data from different domains.

- unitary/multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta, https://huggingface.co/unitary/multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta, (accessed on 16 June 2025) [59]: Based on XLM-RoBERTa, this model was trained on multilingual Wikipedia talk page comments for toxic vs. non-toxic classification. Its broad multilingual scope enables evaluation of cross-lingual generalization to Spanish without fine-tuning, providing a benchmark for assessing how well generic models handle context-sensitive toxicity in domain-specific forums like Mediavida.

3.5. Keyword Overlap Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Annotation Statistics and Dataset Distribution

4.2. Model Performance: Sexism and Racism Detection

4.3. Statistical Significance of Model Comparisons

4.4. Qualitative and Quantitative Error Analysis

- False negative (racism, BETO CTX): “Que ahora tengamos 1123 hijos por pareja no quiere decir que en 2090 vayamos a tener 0. Seguimos siendo superiores intelectualmente (Que es lo que hace predominar una raza sobre otra)…”. English translation: “The fact that we have 1123 kids per couple does not mean that in 2090 we will have 0. We continue to be superior intellectually (Which is what makes a race predominate over another)”. This dialogue explicitly mentions intellectual racial superiority, yet BETO CTX failed to detect racism.

- False positive (sexism, BOW CTX): “…En la empresa privada, sí hay que demostrar más, porque si no, te crujen, que siempre hay alguien jugándose la pasta. Sobre todo en puestos de cierta responsabilidad. Anda que no hay becarios haciendo el trabajo a “personas hechas a si mismas” que son hijos del jefe”. English translation: “…In the private sector, you do have to prove more, because if you don’t, they’ll crack you, because there’s always someone who’s putting their money on the line. Especially in positions of some responsibility. There are no interns doing the work of ‘self-made people’ who are the boss’s kids”. While the content might be controversial, it does not inherently reflect sexism. However, the BOW CTX model mistakenly flagged it as sexist due to possible lexical overlap.

4.5. Comparative Analysis with External Models

4.6. Keyword Overlap Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Annotation Challenges and Guideline Effectiveness

5.2. Error Analysis and Interpretation of Results

5.3. Limitations of Current Models

5.4. Effects and Limitations of Incorporating Multi-Turn Dialogical Context

- Insufficient contextual richness: The Mediavida forum often features short, rapidly-shifting dialogues, where adjacent turns may not always provide enough semantic or pragmatic information to reveal hidden toxicity.

- Fixed context window size: Our two-turn window (preceding the target) may be too narrow for some conversations and not necessary for overly sexist or racist turns, so dynamic window sizes may be worth exploring.

- Model reliance on lexical features: Our error analysis confirmed that, despite contextual input, models tend to prioritize explicit lexical markers (e.g., slurs), with subtle cues from surrounding turns often underweighted.

5.5. Implications for Automatic Hate Speech Moderation

5.6. Future Work

- Cross-lingual and transfer learning: Future studies should investigate cross-lingual transfer learning approaches that leverage annotated data from multiple languages or domains to improve model generalizability and robustness, especially in languages or platforms with limited labeled data. Multilingual transformers and transfer learning can help bridge resource gaps and facilitate rapid adaptation to new domains.

- Semi-supervised and active learning: To address annotation scarcity and improve coverage of rare or subtle phenomena, employing semi-supervised learning (leveraging large amounts of unlabeled data) and active learning (prioritizing the most informative or uncertain samples for human annotation) could significantly improve model performance and annotation efficiency.

- Adaptive context modeling: Exploring architectures that dynamically select or weight relevant turns, rather than relying on fixed context windows, may yield better contextual understanding, especially for implicit bias and sarcasm. Techniques such as hierarchical attention or memory networks could be considered.

- Rich pragmatic and multimodal signals: Incorporating pragmatic cues (e.g., speaker intent, conversation roles, or thread structure) and multimodal information (e.g., accompanying images and metadata) could improve detection of implicit and nuanced forms of bias.

- Bias mitigation and fairness evaluation: Systematic analysis of model and annotation biases, including the cultural perceptions and subjectivities of annotators, should be incorporated, with transparent reporting and fairness audits.

- Multiple expert annotators: Engaging a higher number of annotators with varying expertise coming not only from computer science, but also from social science (to understand systemic sexism/racism and their social dynamics), language (to analyze nuanced language use), and community representatives with life experience from affected groups, among others.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BETO | A BERT model trained on a big Spanish corpus |

| BOW | Bag-of-words |

| CTX | Dialogue in context with two preceding turns |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| FT | Fine-tuning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| ROC-AUC | The area under the ROC curve |

| ST | Single-turn comment |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model type | Transformer (encoder only) |

| Layers | 12 |

| Attention heads | 12 |

| Hidden dimension | 768 |

| Total parameters | 110 million |

| Tokens per input | Up to 512 tokens |

Appendix A.1. Data Preparation

Appendix A.2. Model Configuration and Hyperparameters

| Component | Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer (BETO) | Pretrained model name | dccuchile/bert-base-spanish-wwm-cased |

| Maximum word-piece tokens per window | 512 (model default), split into windows of 128 WP tokens | |

| Stride between windows | 224 WP tokens | |

| Tokenizer/Batching | SpaCy pipeline batch size | 16 |

| Batcher schedule (words per batch) | Compounding from 100 to 1000 (factor 1.001) | |

| Discard oversize examples | true | |

| Batcher tolerance | 0.1 | |

| Training Schedule | Dropout | 0.1 |

| Patience (early stopping) | 0 | |

| Maximum epochs | 20 | |

| Evaluation frequency | Every 200 updates | |

| Optimizer (Adam) | Learning rate () | |

| regularization | 0.01 | |

| Gradient clipping | 1.0 | |

| 0.9 | ||

| 0.999 | ||

| TextCat_Multilabel | Classification threshold | 0.5 |

| Tok2vec pooling strategy | mean pooling over transformer outputs | |

| Linear BoW branch | Enabled (ngram size = 1, vocabulary length = 262,144) |

Appendix A.3. Training Procedure

Appendix A.4. Evaluation Metrics and Validation

Appendix A.5. Reproducibility

References

- Gallegos, I.O.; Rossi, R.A.; Barrow, J.; Tanjim, M.M.; Kim, S.; Dernoncourt, F.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Ahmed, N.K. Bias and Fairness in Large Language Models: A Survey. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 50, 1097–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Lopez, G.; Olteanu, A.; Sim, R.; Wallach, H. Stereotyping Norwegian Salmon: An Inventory of Pitfalls in Fairness Benchmark Datasets. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP), Bangkok, Thailand, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, N.; Poole-Dayan, E.; Reddy, S. An Empirical Survey of the Effectiveness of Debiasing Techniques for Pre-trained Language Models. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Lu, X.; Khashabi, D.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.; Sap, M. ProsocialDialog: A Prosocial Backbone for Conversational Agents. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 4005–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaideh, M.I.; Kwon, O.H.; Radaideh, M.I. Fairness and social bias quantification in Large Language Models for sentiment analysis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 319, 113569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari, L.; Bang, Y.; Su, D.; Chung, W.; Ghadimi, S.; Sameti, H.; Fung, P. Learn What NOT to Learn: Towards Generative Safety in Chatbots. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Barocas, S.; Daumé, H., III; Wallach, H. Language (Technology) is Power: A Critical Survey of “Bias” in NLP. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Online, 5–10 July 2020; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 5454–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Kumar, N.; Zhang, H. Addressing bias in generative AI: Challenges and research opportunities in information management. Inf. Manag. 2025, 62, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.; Goldman, S.; Markey, P.M. Artificial intelligence and human decision making: Exploring similarities in cognitive bias. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Humans 2025, 4, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoldi, B.; Bastings, J.; Bentivogli, L.; Vanmassenhove, E. A decade of gender bias in machine translation. Patterns 2025, 6, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taulé, M.; Nofre, M.; Bargiela, V.; Bonet, X. NewsCom-TOX: A corpus of comments on news articles annotated for toxicity in Spanish. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2024, 58, 1115–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.M.; Luque, F.M.; Zayat, D.; Kondratzky, M.; Moro, A.; Serrati, P.S.; Zajac, J.; Miguel, P.; Debandi, N.; Gravano, A.; et al. Assessing the Impact of Contextual Information in Hate Speech Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 30575–30590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Casabona, A.; Schmeisser-Nieto, W.S.; Nofre, M.; Taulé, M.; Amigó, E.; Chulvi, B.; Rosso, P. Overview of DETESTS at IberLEF 2022: DETEction and Classification of Racial Stereotypes in Spanish. Proces. Leng. Nat. 2022, 69, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kostikova, A.; Wang, Z.; Bajri, D.; Pütz, O.; Paaßen, B.; Eger, S. LLLMs: A Data-Driven Survey of Evolving Research on Limitations of Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.; Klimaszewski, M.; Guillou, L.; Vallor, S.; Birch, A. EuroGEST: Investigating gender stereotypes in multilingual language models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.03867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, B.; Bashir, Z.; Sen, P. Dissecting Bias in LLMs: A Mechanistic Interpretability Perspective. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.05166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, T.; Lehman, E.; Suzgun, M.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Celi, L.A.; Gichoya, J.; Jurafsky, D.; Szolovits, P.; Bates, D.W.; Abdulnour, R.E.E.; et al. Assessing the potential of GPT-4 to perpetuate racial and gender biases in health care: A model evaluation study. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e12–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivetta, G.; Gomez, M.J.; Martinelli, S.; Palombini, P.; Echeveste, M.E.; Mazzeo, N.C.; Busaniche, B.; Benotti, L. HESEIA: A community-based dataset for evaluating social biases in large language models, co-designed in real school settings in Latin America. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.24712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, N.; Stanczak, K.; Rolskov, T.; da Silva Perez, N.; Klein Kafer, N.; Augenstein, I. Measuring Intersectional Biases in Historical Documents. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 2711–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinki, M.; Raj, C.; Mukherjee, A.; Zhu, Z. Measuring South Asian Biases in Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.18466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhune, S.; Padmanabhan, B.; Dutta, K. Do LLMs have a Gender (Entropy) Bias? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, L.; De Nobili, C. More is more: Addition bias in large language models. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Humans 2025, 3, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Lu, Y.; Yang, J. Benford’s Curse: Tracing Digit Bias to Numerical Hallucination in LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.01734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahraei, P.S.; Emami, A. Translate with Care: Addressing Gender Bias, Neutrality, and Reasoning in Large Language Model Translations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.00748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, A.; Bryson, J.J.; Narayanan, A. Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 2017, 356, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.; Wang, A.; Bordia, S.; Bowman, S.R.; Rudinger, R. On Measuring Social Biases in Sentence Encoders. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozza, D.; Bianchi, F.; Hovy, D. HONEST: Measuring Hurtful Sentence Completion in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), Online, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudinger, R.; Naradowsky, J.; Leonard, B.; Van Durme, B. Gender Bias in Coreference Resolution. In Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yatskar, M.; Cotterell, R.; Ordonez, V.; Chang, K.W. Gender Bias in Contextualized Word Embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmassenhove, E.; Emmery, C.; Shterionov, D. NeuTral Rewriter: A Rule-Based and Neural Approach to Automatic Rewriting into Gender Neutral Alternatives. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 8940–8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.; Recasens, M.; Axelrod, V.; Baldridge, J. Mind the GAP: A Balanced Corpus of Gendered Ambiguous Pronouns. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Dadu, T. Incorporating Subjectivity into Gendered Ambiguous Pronoun (GAP) Resolution using Style Transfer. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing (GeBNLP), Seattle, WA, USA, 15 July 2022; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Lazar, K.; Stanovsky, G. Collecting a Large-Scale Gender Bias Dataset for Coreference Resolution and Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 16–20 November 2021; pp. 2470–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Bethke, A.; Reddy, S. StereoSet: Measuring stereotypical bias in pretrained language models. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP), Bangkok, Thailand, 1–6 August 2021; Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 5356–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, M.; Nissim, M.; Gatt, A. Unmasking Contextual Stereotypes: Measuring and Mitigating BERT’s Gender Bias. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing, Barcelona, Spain, 13 December 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangia, N.; Vania, C.; Bhalerao, R.; Bowman, S.R. CrowS-Pairs: A Challenge Dataset for Measuring Social Biases in Masked Language Models. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felkner, V.; Chang, H.C.H.; Jang, E.; May, J. WinoQueer: A Community-in-the-Loop Benchmark for Anti-LGBTQ+ Bias in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 9126–9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barikeri, S.; Lauscher, A.; Vulić, I.; Glavaš, G. RedditBias: A Real-World Resource for Bias Evaluation and Debiasing of Conversational Language Models. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP), Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1941–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.; Wang, X.; Tenney, I.; Beutel, A.; Pitler, E.; Pavlick, E.; Chen, J.; Chi, E.; Petrov, S. Measuring and Reducing Gendered Correlations in Pre-trained Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.06032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.; Ross, C.; Fernandes, J.; Smith, E.M.; Kiela, D.; Williams, A. Perturbation Augmentation for Fairer NLP. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 11 December 2022; pp. 9496–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritchenko, S.; Mohammad, S.M. Examining Gender and Race Bias in Two Hundred Sentiment Analysis Systems. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.04508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.; Li, T.; Phillips, J.; Srikumar, V. On Measuring and Mitigating Biased Inferences of Word Embeddings. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.09369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehman, S.; Gururangan, S.; Sap, M.; Choi, Y.; Smith, N.A. RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 3356–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamala, J.; Sun, T.; Kumar, V.; Krishna, S.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Chang, K.W.; Gupta, R. BOLD: Dataset and Metrics for Measuring Biases in Open-Ended Language Generation. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT’21, Online, 3–10 March 2021; pp. 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.M.; Hall, M.; Kambadur, M.; Presani, E.; Williams, A. “I’m sorry to hear that”: Finding New Biases in Language Models with a Holistic Descriptor Dataset. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 9180–9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Y, P.S.; Sun, L. TrustGPT: A Benchmark for Trustworthy and Responsible Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, L. Implicit Bias in LLMs: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.02776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fersini, E.; Rosso, P.; Anzovino, M. Overview of the Task on Automatic Misogyny Identification at IberEval 2018. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Evaluation of Human Language Technologies for Iberian Languages (IberEval 2018), Seville, Spain, 18 September 2018; CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Volume 2150, pp. 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Carmona, M.; Guzmán-Falcón, E.; Montes-Gómez, M.; Escalante, H.J.; Villaseñor-Pineda, L.; Reyes-Meza, V.; Rico-Sulayes, A. Overview of MEX-A3T at IberEval 2018: Authorship and Aggressiveness Analysis in Mexican Spanish Tweets. In Proceedings of the 3rd SEPLN Workshop on Evaluation of Human Language Technologies for Iberian Languages (IberEval), Seville, Spain, 18 September 2018; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón, M.E.; Jarquín-Vásquez, H.J.; Montes-Gómez, M.; Escalante, H.J.; Pineda, L.V.; Gómez-Adorno, H.; Posadas-Durán, J.P.; Bel-Enguix, G. Overview of MEX-A3T at IberLEF 2020: Fake News and Aggressiveness Analysis in Mexican Spanish. In Proceedings of the Iberian Languages Evaluation Forum (IberLEF 2020) at SEPLN, Malaga, Spain, 23–25 September 2020; pp. 222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, V.; Bosco, C.; Fersini, E.; Nozza, D.; Patti, V.; Rangel Pardo, F.M.; Rosso, P.; Sanguinetti, M. SemEval-2019 Task 5: Multilingual Detection of Hate Speech Against Immigrants and Women in Twitter. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–7 June 2019; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Kohatsu, J.C.; Quijano-Sánchez, L.; Liberatore, F.; Camacho-Collados, M. Detecting and Monitoring Hate Speech in Twitter. Sensors 2019, 19, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; de Albornoz, J.C.; Plaza, L.; Gonzalo, J.; Rosso, P.; Comet, M.; Donoso, T. Overview of EXIST 2021: sEXism Identification in Social neTworks. Proces. Leng. Nat. 2021, 67, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; de Albornoz, J.C.; Plaza, L.; Mendieta-Aragón, A.; Marco-Remón, G.; Makeienko, M.; Plaza, M.; Gonzalo, J.; Spina, D.; Rosso, P. Overview of EXIST 2022: sEXism Identification in Social neTworks. Proces. Leng. Nat. 2022, 69, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- del Arco, F.M.P.; Casavantes, M.; Escalante, H.J.; Martín-Valdivia, M.T.; Montejo-Ráez, A.; y Gómez, M.M.; Jarquín-Vásquez, H.; Villaseñor-Pineda, L. Overview of MeOffendEs at IberLEF 2021: Offensive Language Detection in Spanish Variants. Proces. Leng. Nat. 2021, 67, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeade, T.; Cignarella, A.T.; Frenda, S.; Laurent, M.; Schmeisser-Nieto, W.S.; Benamara, F.; Bosco, C.; Moriceau, V.; Patti, V.; Taulé, M. A Multilingual Dataset of Racial Stereotypes in Social Media Conversational Threads. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2–6 May 2023; pp. 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, J.; Chaperon, G.; Fuentes, R.; Ho, J.H.; Kang, H.; Pérez, J. Spanish Pre-Trained BERT Model and Evaluation Data. In Proceedings of the PML4DC at ICLR 2020, Online, 26 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, A.F.M.D.; Silva, R.F.D.; Schlicht, I.B. Sexism Prediction in Spanish and English Tweets Using Monolingual and Multilingual BERT and Ensemble Models. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Kharkiv, Ukraine, 20–21 September 2021; pp. 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanu, L.; Unitary Team. Detoxify. Github. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/unitaryai/detoxify (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Laurençon, H.; Saulnier, L.; Wang, T.; Akiki, C.; Villanova del Moral, A.; Le Scao, T.; Von Werra, L.; Mou, C.; González Ponferrada, E.; Nguyen, H.; et al. The BigScience ROOTS Corpus: A 1.6TB Composite Multilingual Dataset. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; Koyejo, S., Mohamed, S., Agarwal, A., Belgrave, D., Cho, K., Oh, A., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 35, pp. 31809–31826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buie, H.; Croft, A. The Social Media Sexist Content (SMSC) Database: A Database of Content and Comments for Research Use. Collabra Psychol. 2023, 9, 71341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.J.; Carrillo-de Albornoz, J.; Plaza, L. Automatic Classification of Sexism in Social Networks: An Empirical Study on Twitter Data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 219563–219576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Bansal, A.; Bhagat, A.; Dawer, Y.; Lahiri, B.; Ojha, A.K. Developing a Multilingual Annotated Corpus of Misogyny and Aggression. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Trolling, Aggression and Cyberbullying, Marseille, France, 16 May 2020; pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M.S.; Oussalah, M. A systematic review of hate speech automatic detection using natural language processing. Neurocomputing 2023, 546, 126232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouka, E.; Saridakis, I. Racism Goes to the Movies: A Corpus-Driven Study of Cross-Linguistic Racist Discourse Annotation and Translation Analysis; Language Science Press: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 35–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Reganti, A.N.; Bhatia, A.; Maheshwari, T. Aggression-annotated Corpus of Hindi-English Code-mixed Data. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), Miyazaki, Japan, 7–12 May 2018; Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Cieri, C., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Hasida, K., Isahara, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Mazo, H., et al., Eds.; European Language Resources Association: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.J. Gendered harassment in secondary schools: Understanding teachers’ (non) interventions. Gend. Educ. 2008, 20, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Rivers, I. The use of homophobic language across bullying roles during adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 31, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraïssé, C.; Barrientos, J. The concept of homophobia: A psychosocial perspective. Sexologies 2016, 25, e65–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, C. Naming the “outsider within”: Homophobic pejoratives and the verbal abuse of lesbian, gay and bisexual high-school pupils. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthi, B.R.; Priyadharshini, R.; Ponnusamy, R.; Kumaresan, P.K.; Sampath, K.; Thenmozhi, D.; Thangasamy, S.; Nallathambi, R.; McCrae, J.P. Dataset for Identification of Homophobia and Transophobia in Multilingual YouTube Comments. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.00227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, J.; Andersen, S.; Bel-enguix, G.; Gómez-adorno, H.; Ojeda-trueba, S.l. HOMO-MEX: A Mexican Spanish Annotated Corpus for LGBT+phobia Detection on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Online Abuse and Harms (WOAH), Toronto, ON, Canada, 13 July 2023; Chung, Y.l., Röttger, P., Nozza, D., Talat, Z., Mostafazadeh Davani, A., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts, A.C. Aporofobia, el Rechazo al Pobre. Un Desafío Para la Democracia; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comim, F.; Borsi, M.T.; Valerio Mendoza, O. The Multi-Dimensions of Aporophobia; MPRA Paper 103124; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, W. Reforming the Poor. Soc. Work 1972, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño Argüelles, Y.L.; Álvarez Santana, C.L.; Giovanni Locatelli, F. Migración Venezolana, Aporofobia en Ecuador y Resiliencia de los Inmigrantes Venezolanos en Manta, Periodo 2020. Rev. San Gregor. 2020, 43, 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Navarro, E. Aporofobia. In Glosario Para una Sociedad Intercultural; Conill, J., Ed.; Bancaja: Valencia, Spain, 2002; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Picado, E.M.V.; Yurrebaso Macho, A.; Guzmán Ordaz, R. Respuesta social ante la aporofobia: Retos en la intervención social. IDP. Rev. Internet Derecho PolíTica 2022, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassignana, E.; Basile, V.; Patti, V. Hurtlex: A Multilingual Lexicon of Words to Hurt. In Proceedings of the 5th Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics (CLiC-it 2018), Torino, Italy, 10–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Source | Size | % Toxic | Phenomenon/ Task | Main Target | Annotation Scheme | Context * | Annotators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI-2018 | 4138 | 49.8 | Misogyny | Women | multi-level | — | crowd + 3 exp. | [48] | |

| MEX-A3T (18/20) | 11,856/ 10,475 | 29.6/ 28.7 | Aggressiveness | Generic/ Women | binary | — | 2 exp. | [49,50] | |

| HateEval-2019 | 6600 | 41.5 | Hate speech | Women, migration | multi-level | — | crowd + 2 exp. | [51] | |

| HaterNet-2019 | 6000 | 26 | Hate speech | — | binary | — | 4 exp. | [52] | |

| EXIST 2021/2022 | Twitter, Gab | 5701/ 6226 | ≈50 | Sexism | Women | multi-class | — | crowd + ≥5 exp. | [53,54] |

| OffendES | Tw., YT, IG | 30416 | 12.8 | Offensiveness | Generic | 5-class | — | 3–10 exp. | [55] |

| OffendMEX | 7319 | 27.6 | Offensiveness | Generic | multi-class | — | 3 exp. | [55] | |

| Context. Hate Speech | 56,869 | 15.3 | Hate speech | Women, migration, LGBTI+, disabled… | multi-class | ✓ | 6 exp. | [12] | |

| NewsCom-TOX | News comments | 4359 | 31.9 | Toxicity | Immigration | multi-level | — | 4 exp. | [11] |

| DETESTS-Dis | News, Digital media | 10,978 | ≈40 | Stereotype detection (explicit/implicit) | Immigration | binary + implicitness | ✓ | 3 exp. | [13,56] |

| EsCorpiusBias | Mediavida forum | 1990 † | ≈26 | Sexism/Racism | Women, migration | binary | ✓ | 2 exp. | This work |

| Model | Base Transformer | Target Phenomena (Labels) | Additional Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BETO Offensiveness [55] | BETO (Spanish BERT) | Offensiveness (5 classes: Non-offensive, Offensive, etc.) | Evaluated on multiple platforms: Twitter, YouTube, Instagram |

| Contextualized Hate Speech [12] | BETO (Spanish BERT) | Hate speech (multiclass: sexism, racism, LGBTI+ hate, disability hate, etc.) | Context-aware embeddings; trained on news-site comments (multi-turn context) |

| HaterNet [52] | CNN + linguistic features | Hate speech (binary: hate, non-hate) | Uses user-level metadata and linguistic features; specifically tailored for Twitter |

| Multilingual Transformers [58] | mBERT, XLM-RoBERTa | Hate speech, aggressiveness, offensive language (binary and multiclass) | Compares multilingual transformers to BETO; highlights performance benefits of BETO |

| Multilingual Toxic-XLM-RoBERTa [59] | XLM-RoBERTa | General toxicity (multiple: toxicity, severe_toxicity, obscene, threat, etc.) | Trained on multilingual Wikipedia talk page comments; effective cross-lingual generalization capabilities |

| Label | Definition | Annotation Guidelines | Sample Dialogue (with Translation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexism | Discrimination or prejudiced statements based on gender, reinforcing stereotypes or inequalities. | Annotators evaluate dialogues for manifestations such as hostile, benevolent, objectifying, ideological, or stereotypical sexism. Annotation is context-dependent and requires assessing subtle cues within the conversation. | Sexist Example: “Es que es obvio, los videojuegos de siempre han sido cosa de hombres…” (“It’s obvious, videogames have always been a guy thing…”) |

| Non-Sexism | Absence of gender-based discriminatory or prejudiced statements. | Annotators confirm no sexist elements exist within dialogue context, ensuring neutral or inclusive expressions. | Non-Sexist Example: “Que yo sepa la mayoría de competiciones permite competir a ambos sexos…” (“As far as I know, most competitions allow both sexes…”) |

| Racism | Expressions involving prejudice or discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or national origin, whether overt or implicit. | Annotators identify dialogues containing affective, evaluative, judgmental, overt or covert racism, and stereotyping. Contextual understanding is crucial to detect subtle or ambiguous manifestations. | Racist Example: “El camarero no puso mesa de infraseres…ha puesto mesa acorde a lo que son, gitanos…” (“The waiter didn’t write ’table of subhumans’…he wrote a table according to what they are, gypsies…”) |

| Non-Racism | Absence of racially prejudiced or discriminatory statements. | Annotators ensure no racist or xenophobic elements are present, confirming the dialogue context is neutral or inclusive. | Non-Racist Example: “Sí que es verdad que aquí en Francia cuando eres autónomo hay diferentes categorias y a lo mejor tu categoría sería diferente a la mía.” (“It is true that here in France when you are self-employed there are different categories and maybe your category would be different from mine.”) |

| Spanish Dialogue |

|---|

| <Context> Claro claro, cuéntame más. A mi si un gitano me viene de buenas, le voy a contestar de buenas, pero nunca vienen de buenas. |

| <Context> Cuando habláis de gitanos en el estudio os referís a la escoria entiendo yo (…) el 99% son escoria, eso es así (…), ya dije que a un gitano que me trate normal lo voy a tratar normal, pero todavía no he conocido a ningún gitano que lo haga. |

| <Turn being annotated> Además de estar de acuerdo con vosotros, un poco cutre los primeros histogramas del estudio donde ni siquiera ponen nada en los ejes. Debería darle vergüenza al grupo de investigadores que está elaborando los datos. |

| English Translation |

| <Context> Of course, tell me more. If a gypsy is nice to me, I’m going to answer him nicely, but they never come nicely. |

| <Context> When you talk about gypsies in the study you mean the scum I understand (…) 99% are scum, that’s how it is (…), I’ve already said that I will treat a gypsy who treats me normally, but I haven’t met any gypsies who do that yet. |

| <Turn being annotated> Besides agreeing with you, the first histograms of the study where they don’t even put anything on the axes are a bit crappy. Shame on the group of researchers who are producing the data. |

| Spanish Dialogue |

|---|

| <Context> Quería decir italianas pero me pudo la emoción. Mujeres italianas y hombres españoles. Eslovenia tiene las mujeres más guapas por mucho que diga esa web. |

| <Context> las eslovenas y las checas…y encima la cerveza buena y barata. |

| <Turn being annotated> pruebas de las eslovenas para afirmar eso. Checoslovaquia no se tuvo que separar nunca. |

| English Translation |

| <Context> I wanted to say Italian women but I was overcome with emotion. Italian women and Spanish men. Slovenia has the most beautiful women, no matter what that website says. |

| <Context> Slovenian and Czech ones… and good, cheap beer on top of that. |

| <Turn being annotated> Slovenian evidence to support this. Czechoslovakia never had to split. |

| Dataset | Training | Oversampled Training | Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racism | 792 | 1096 | 197 |

| Sexism | 800 | 1258 | 199 |

| Metric | Sexism Dataset | Racism Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| Total annotated dialogues | 1001 | 989 |

| Positive examples (%) | 22.1% | 30.2% |

| Negative examples (%) | 77.9% | 69.8% |

| Mean tokens per example | 133.3 | 123.7 |

| Median tokens | 103 | 94 |

| Maximum tokens | 957 | 784 |

| Cohen’s Kappa () | 0.55 | 0.79 |

| Model | Train/FT | Evaluate | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | ROC–AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexism Detection | ||||||

| LogReg baseline | ST | ST | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.77 |

| LogReg baseline | CTX | CTX | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.82 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | ST | ST | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | CTX | CTX | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.81 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | ST | ST | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.85 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | CTX | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.87 |

| HF piuba-contextualized | – | ST | 0.86 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.84 |

| HF piuba-contextualized | – | CTX | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.82 |

| HF multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta | – | ST | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| HF multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta | – | CTX | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.62 |

| Racism Detection | ||||||

| LogReg baseline | ST | ST | 0.86 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.87 |

| LogReg baseline | CTX | CTX | 0.93 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.89 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | ST | ST | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.88 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | CTX | CTX | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | ST | ST | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.94 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | CTX | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| HF piuba-contextualized | – | ST | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.82 |

| HF piuba-contextualized | – | CTX | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.79 |

| HF multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta | – | ST | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.70 |

| HF multilingual-toxic-xlm-roberta | – | CTX | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.65 |

| Setting | Model Pair | F1 Difference | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racism Detection | |||

| ST | BETO vs. BOW | 0.814 vs. 0.644 | 0.0522 |

| ST | BETO vs. LogReg | 0.814 vs. 0.660 | 0.0614 |

| ST | BOW vs. LogReg | 0.644 vs. 0.660 | 1.0000 |

| CTX | BETO vs. BOW | 0.745 vs. 0.717 | 0.8506 |

| CTX | BETO vs. LogReg | 0.745 vs. 0.610 | 0.5966 |

| CTX | BOW vs. LogReg | 0.717 vs. 0.610 | 0.2101 |

| Sexism Detection | |||

| ST | BETO vs. BOW | 0.667 vs. 0.305 | 0.4799 |

| ST | BETO vs. LogReg | 0.667 vs. 0.328 | 0.2203 |

| ST | BOW vs. LogReg | 0.305 vs. 0.328 | 0.4807 |

| CTX | BETO vs. BOW | 0.673 vs. 0.568 | 0.5966 |

| CTX | BETO vs. LogReg | 0.673 vs. 0.538 | 0.8506 |

| CTX | BOW vs. LogReg | 0.568 vs. 0.538 | 0.8318 |

| Model | Variant | TP | FP | FN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racism Detection | ||||

| LogReg baseline | ST | 31 | 5 | 27 |

| LogReg baseline | CTX | 25 | 2 | 30 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | ST | 46 | 9 | 12 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | 41 | 14 | 14 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | ST | 29 | 3 | 29 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | CTX | 33 | 4 | 22 |

| Sexism Detection | ||||

| LogReg baseline | ST | 11 | 10 | 35 |

| LogReg baseline | CTX | 21 | 8 | 28 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | ST | 35 | 24 | 11 |

| HF BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | 35 | 20 | 14 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | ST | 9 | 4 | 37 |

| TextCatBOW (SpaCy) | CTX | 25 | 14 | 24 |

| Model | Variant | Positives w/ Slur (%) | Negatives w/ Slur (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexism | |||

| BETO (SpaCy) | ST | 89.83% (53/59) | 69.29% (97/140) |

| BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | 100.00% (55/55) | 97.92% (141/144) |

| TextCatBOW | ST | 92.31% (12/13) | 74.19% (138/186) |

| TextCatBOW | CTX | 100.00% (39/39) | 98.12% (157/160) |

| Racism | |||

| BETO (SpaCy) | ST | 96.36% (53/55) | 66.20% (94/142) |

| BETO (SpaCy) | CTX | 100.00% (55/55) | 96.48% (137/142) |

| TextCatBOW | ST | 96.88% (31/32) | 70.30% (116/165) |

| TextCatBOW | CTX | 100.00% (37/37) | 96.88% (155/160) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kharitonova, K.; Pérez-Fernández, D.; Gutiérrez-Hernando, J.; Gutiérrez-Fandiño, A.; Callejas, Z.; Griol, D. EsCorpiusBias: The Contextual Annotation and Transformer-Based Detection of Racism and Sexism in Spanish Dialogue. Future Internet 2025, 17, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17080340

Kharitonova K, Pérez-Fernández D, Gutiérrez-Hernando J, Gutiérrez-Fandiño A, Callejas Z, Griol D. EsCorpiusBias: The Contextual Annotation and Transformer-Based Detection of Racism and Sexism in Spanish Dialogue. Future Internet. 2025; 17(8):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17080340

Chicago/Turabian StyleKharitonova, Ksenia, David Pérez-Fernández, Javier Gutiérrez-Hernando, Asier Gutiérrez-Fandiño, Zoraida Callejas, and David Griol. 2025. "EsCorpiusBias: The Contextual Annotation and Transformer-Based Detection of Racism and Sexism in Spanish Dialogue" Future Internet 17, no. 8: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17080340

APA StyleKharitonova, K., Pérez-Fernández, D., Gutiérrez-Hernando, J., Gutiérrez-Fandiño, A., Callejas, Z., & Griol, D. (2025). EsCorpiusBias: The Contextual Annotation and Transformer-Based Detection of Racism and Sexism in Spanish Dialogue. Future Internet, 17(8), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17080340