Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Facial Expression Analysis for Mental Health Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

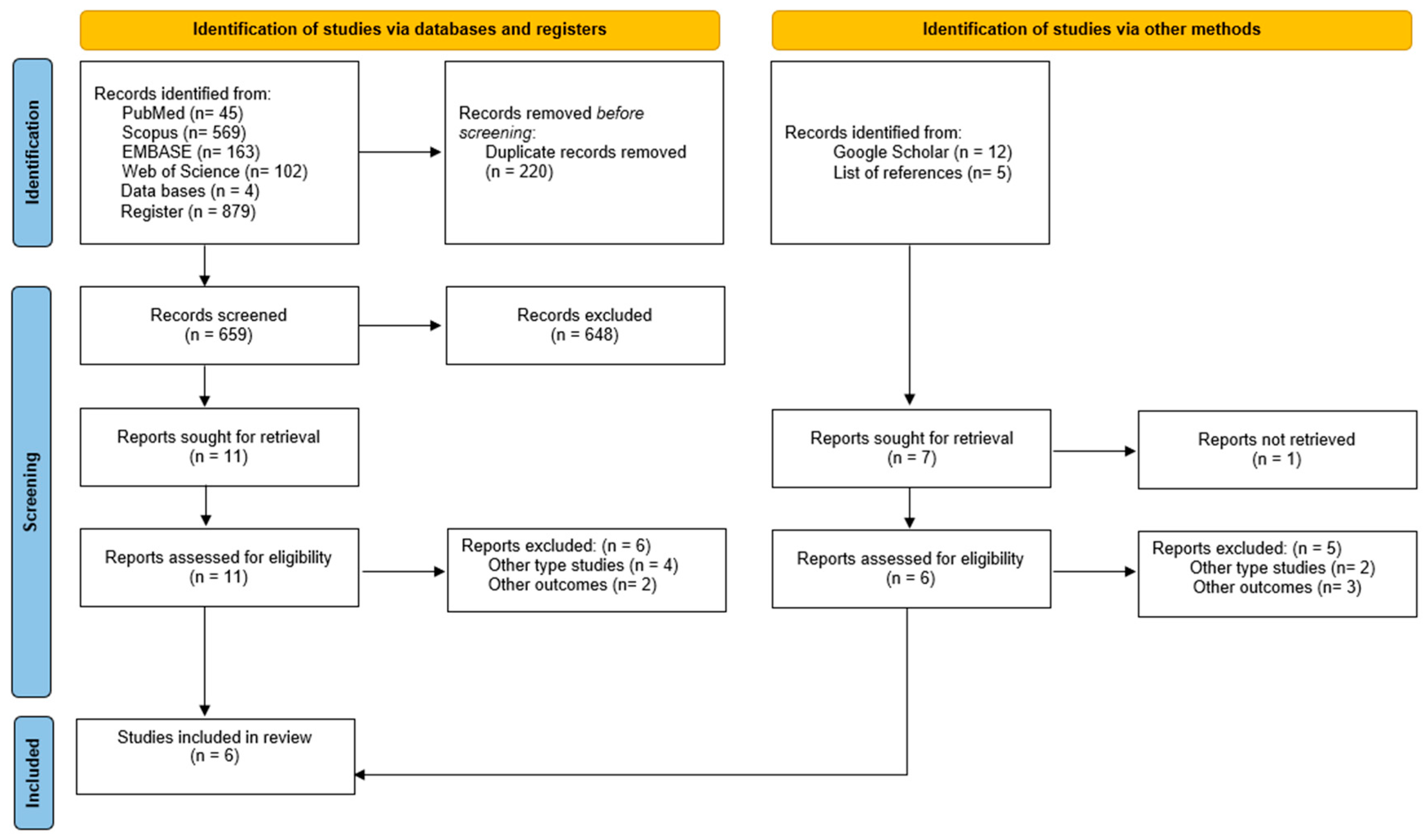

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Extraction Process

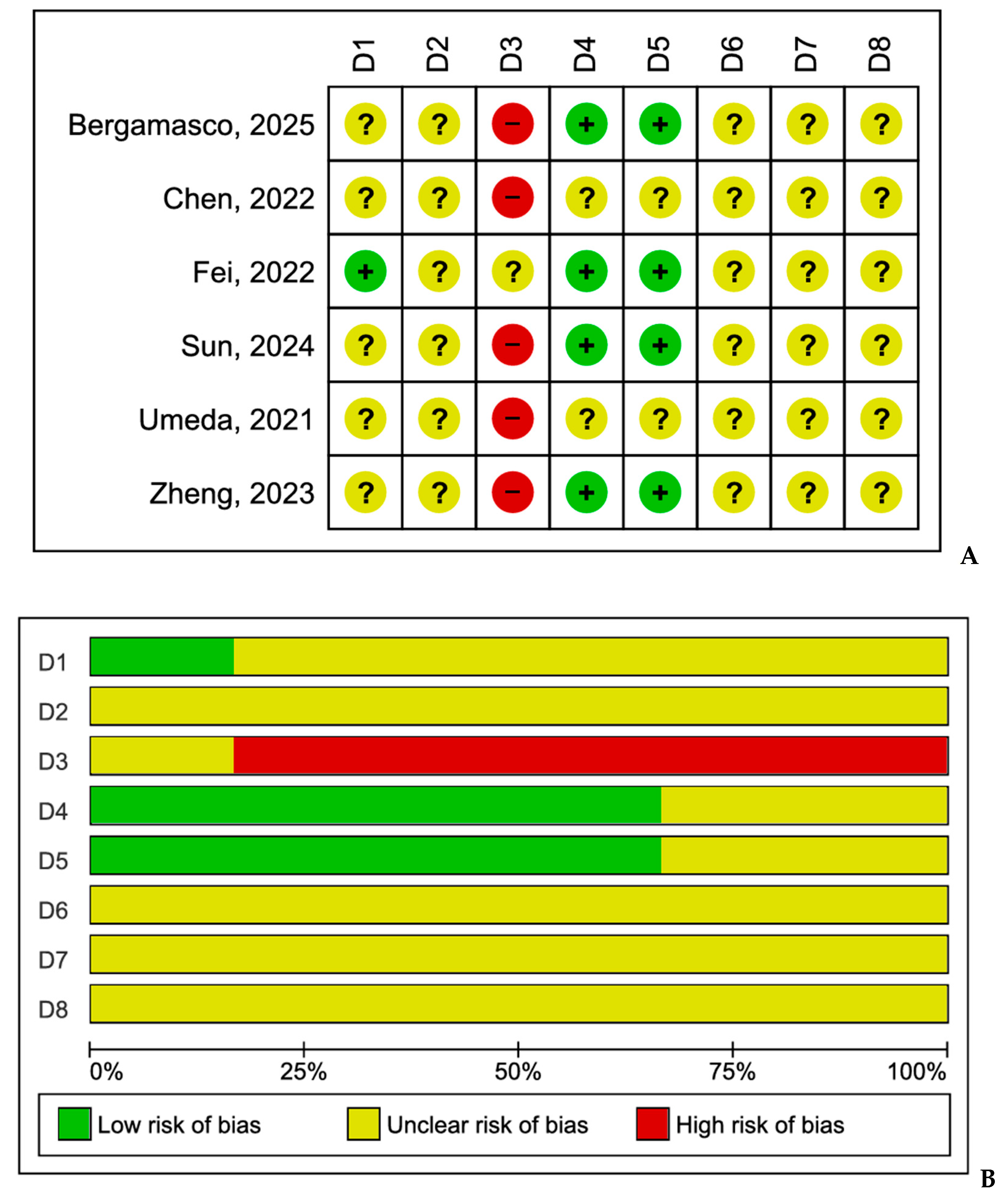

2.7. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Characteristics of Artificial Intelligence and Facial Recognition

3.4. AI Accuracy for Facial Expressions in Adults

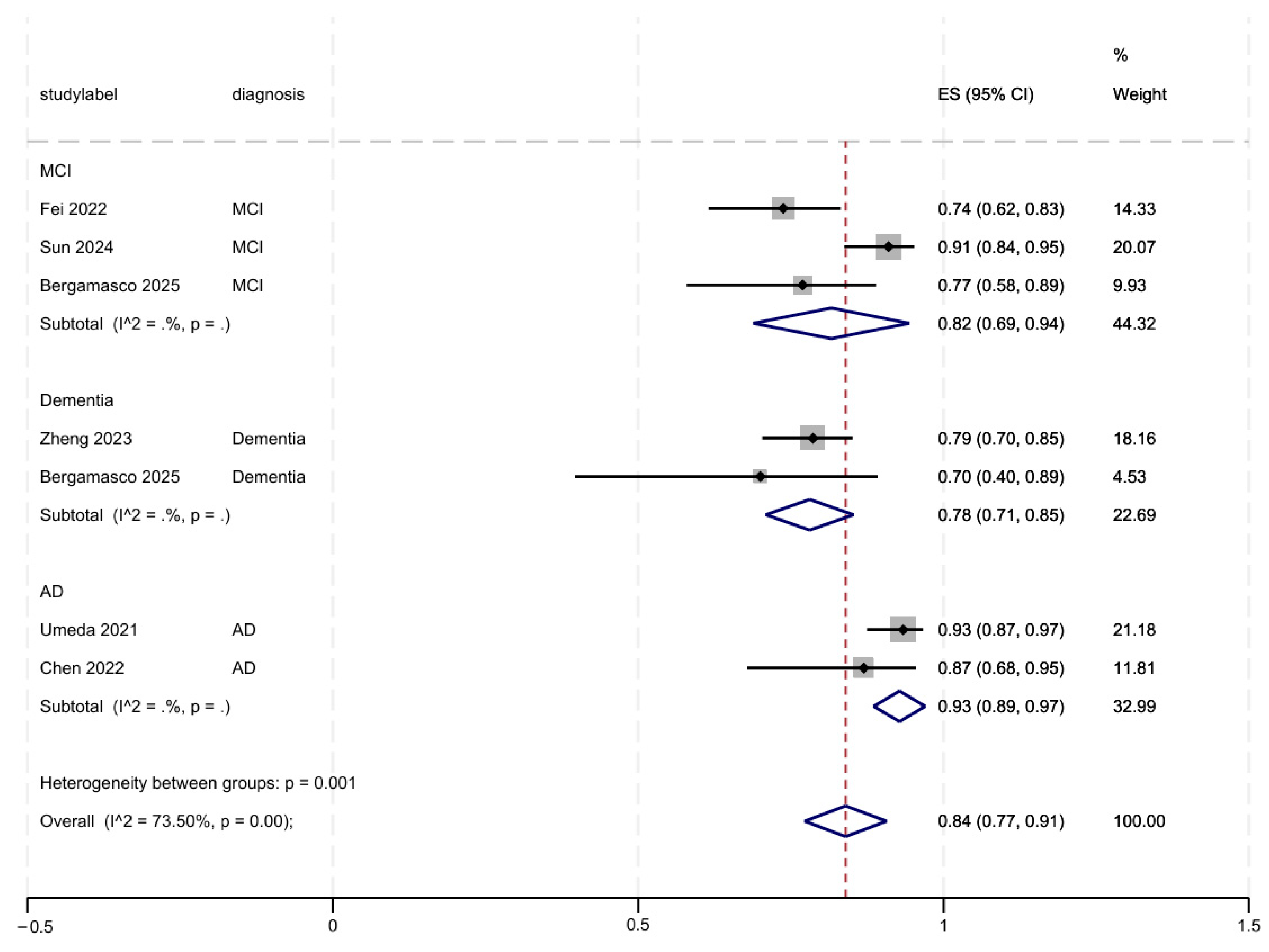

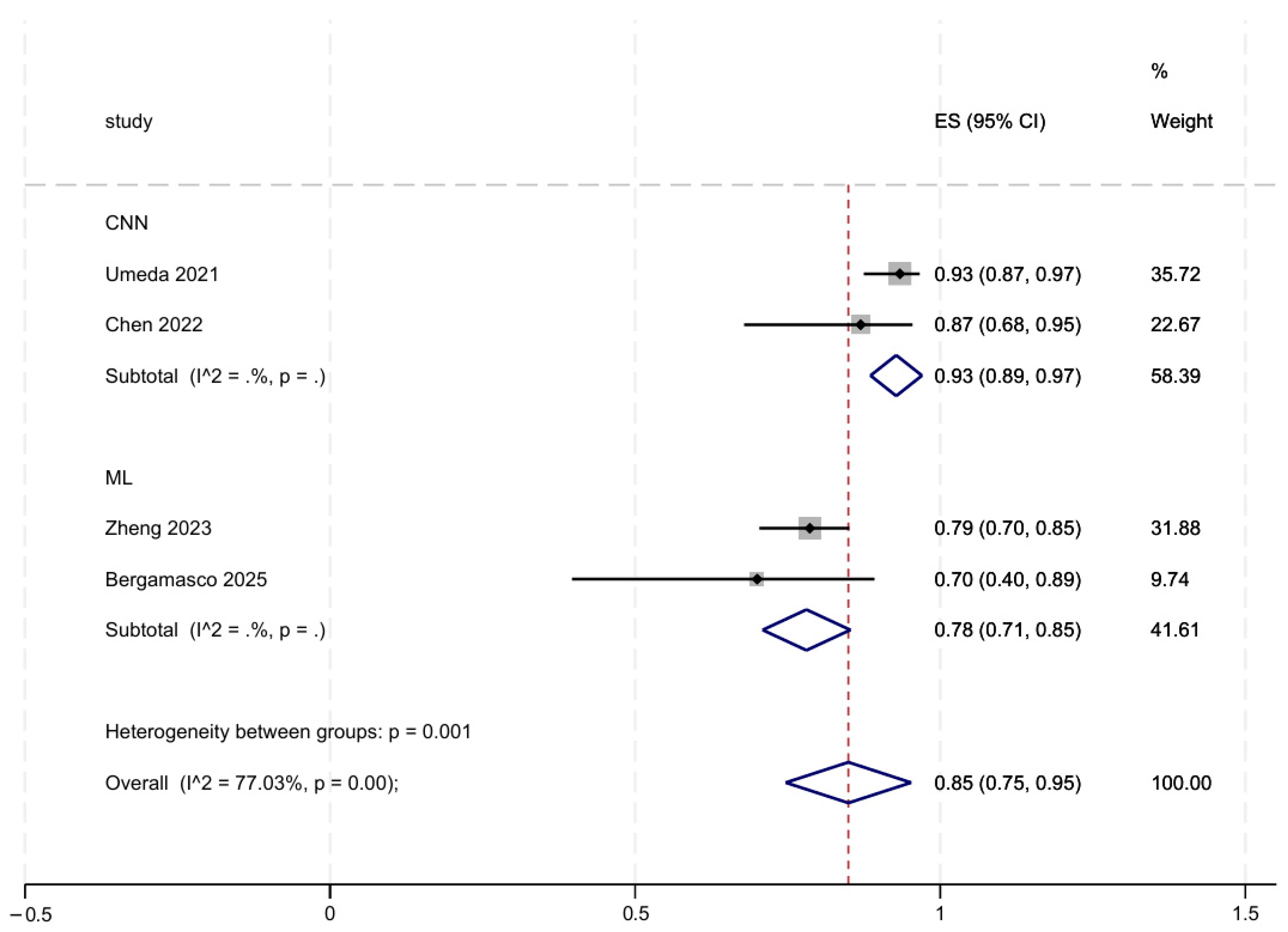

3.5. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

3.6. Risk of Bias and Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethical and Practical Considerations

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Strengths

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renn, B.N.; Schurr, M.; Zaslavsky, O.; Pratap, A. Artificial Intelligence: An Interprofessional Perspective on Implications for Geriatric Mental Health Research and Care. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 734909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.D.; Prudhviraj, G.; Vijay, K.; Kumar, P.S.; Plugmann, P. Exploring COVID-19 Through Intensive Investigation with Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm. In Handbook of Artificial Intelligence and Wearables; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhou, Z. Evaluation and Comparison of Ten Machine Learning Classification Models Based on the Mobile Users Experience. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Science (EIECS), Changchun, China, 22–24 September 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 767–771. [Google Scholar]

- Weitz, K.; Hassan, T.; Schmid, U.; Garbas, J.U. Deep-learned faces of pain and emotions: Elucidating the differences of facial expressions with the help of explainable AI methods. Tech. Mess. 2019, 86, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.A.; Lee, E.E.; Jeste, D.V.; Van Patten, R.; Twamley, E.W.; Nebeker, C.; Yamada, Y.; Kim, H.-C.; Depp, C.A. Artificial Intelligence Approaches to Predicting and Detecting Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A Conceptual Review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C.; Xu, C.; Nguyen, C.H.; Geng, Y.; Pfob, A.; Sidey-Gibbons, C. Machine Learning-Based Short-Term Mortality Prediction Models for Patients with Cancer Using Electronic Health Record Data: Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e33182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, A.M.; Curtis, S.H.; Weir, I.B.; Stout, J.J.; Barry, B.A.; Bobo, W.V.; Athreya, A.P.; Sharp, R.R. Physician Perspectives on the Potential Benefits and Risks of Applying Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatric Medicine: Qualitative Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e64414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Guerra, D.D.; Hernández-Lugo, M.d.l.C.; Broche-Pérez, Y.; Ramos-Galarza, C.; Iglesias-Serrano, E.; Fernández-Fleites, Z. AI-assisted neurocognitive assessment protocol for older adults with psychiatric disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1516065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Ocampo, D.; Toledo-Fernández, A.; González-González, A. Mental Health Changes in Older Adults in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study in Mexico. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 848635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, R.; De Marco, M.; Venneri, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Infection and Enforced Prolonged Social Isolation on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Older Adults with and Without Dementia: A Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 585540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.; Ward, M.; DiCosimo, A.; Baunta, S.; Cunningham, C.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Kenny, R.A.; Purcell, R.; Lannon, R.; McCarroll, K.; et al. Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM 2021, 114, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoo, J.; Haddad, P.M.; Mistry, M.; Wadoo, O.; Islam, S.M.S.; Jan, F.; Iqbal, Y.; Howseman, T.; Riley, D.; Alabdulla, M. The COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity to make mental health a higher public health priority. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, N.; Matcham, F.; Klapper, J.; Schuller, B. Artificial intelligence to aid the detection of mood disorders. In Artificial Intelligence in Precision Health; Barh, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi, N.; Taheri, Z.; Nezhad Salari, A.M.; Kazemzadeh, K.; Tafakhori, A. Recognition and classification of facial expression using artificial intelligence as a key of early detection in neurological disorders. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 36, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, B.C. A brief review of facial emotion recognition based on visual information. Sensors 2018, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P.; Cordaro, D. What is meant by calling emotions basic. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, R.; O’Connor, K.B.; Davis, J.M.; Irons, J.; McKone, E. New tests to measure individual differences in matching and labelling facial expressions of emotion, and their association with ability to recognise vocal emotions and facial identity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifelo, Z.; Ding, J.; Ning, H.; Qurat-Ul-Ain; Dhelim, S. Artificial intelligence-enabled metaverse for sustainable smart cities: Technologies, applications, challenges, and future directions. Electronics 2024, 13, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Jones, A.B.; Hilty, D. Geriatric Telepsychiatry in Academic Settings. In Geriatric Telepsychiatry: A Clinician’s Guide; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 55–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Ralescu, A.L. Future Internet architectures on an emerging scale—A systematic review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taati, B.; Zhao, S.; Ashraf, A.B.; Asgarian, A.; Browne, M.E.; Prkachin, K.M.; Mihailidis, A.; Hadjistavropoulos, T. Algorithmic bias in clinical populations—Evaluating and improving facial analysis technology in older adults with dementia. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 25527–25534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Prisma-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejani, A.S.; Klontzas, M.E.; Gatti, A.A.; Mongan, J.T.; Moy, L.; Park, S.H.; Kahn, C.E., Jr.; CLAIM 2024 Update Panel. Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): 2024 update. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, e240300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda-Kameyama, Y.; Kameyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Son, B.K.; Kojima, T.; Fukasawa, M.; Iizuka, T.; Ogawa, S.; Iijima, K.; Akishita, M. Screening of Alzheimer’s disease by facial complexion using artificial intelligence. Aging 2021, 13, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Tsai, T.H.; Ho, A.; Li, C.H.; Ke, L.J.; Peng, L.N.; Lin, M.-H.; Hsiao, F.-Y.; Chen, L.-K. Predicting neuropsychiatric symptoms of persons with dementia in a day care center using a facial expression recognition system. Aging 2022, 14, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Yang, E.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W. A novel deep neural network-based emotion analysis system for automatic detection of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Neurocomputing 2022, 468, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Bouazizi, M.; Ohtsuki, T.; Kitazawa, M.; Horigome, T.; Kishimoto, T. Detecting dementia from face-related features with automated computational methods. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Dodge, H.H.; Mahoor, M.H. MC-ViViT: Multi-branch Classifier-ViViT to detect mild cognitive impairment in older adults using facial videos. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamasco, L.; Coletta, A.; Olmo, G.; Cermelli, A.; Rubino, E.; Rainero, I. AI-Based Facial Emotion Analysis for Early and Differential Diagnosis of Dementia. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, G.; Defeudis, A.; Giannini, V.; Mazzetti, S.; Regge, D. Artificial Intelligence in Oncologic Imaging. In Multimodality Imaging and Intervention in Oncology; Neri, E., Erba, P.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Turcian, D.; Stoicu-Tivadar, V. Real-Time Detection of Emotions Based on Facial Expression for Mental Health. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 309, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Iyortsuun, N.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jhon, M.; Yang, H.J.; Pant, S. A Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches on Mental Health Diagnosis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arji, G.; Erfannia, L.; Alirezaei, S.; Hemmat, M. A systematic literature review and analysis of deep learning algorithms in mental disorders. Informatics Med. Unlocked 2023, 40, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Li, W.; Zeng, A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y. CmdVIT: A Voluntary Facial Expression Recognition Model for Complex Mental Disorders. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 3013–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosen, K.S.; Lemvigh, C.K.; Nielsen, M.Ø.; Glenthøj, B.Y.; Syeda, W.T.; Ebdrup, B.H. Using computer vision of facial expressions to assess symptom domains and treatment response in antipsychotic-naïve patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2025, 151, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomiya, H.; Shimokawa, K.; Namba, S.; Osumi, M.; Sato, W. An Artificial Intelligence Model for Sensing Affective Valence and Arousal from Facial Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, W.; Yao, X.; Xue, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Developing a machine learning model for detecting depression, anxiety, and apathy in older adults with mild cognitive impairment using speech and facial expressions: A cross-sectional observational study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 146, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Yang, E.; Li, D.D.U.; Butler, S.; Ijomah, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Deep convolution network based emotion analysis towards mental health care. Neurocomputing 2020, 388, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwani, T.; Relton, S.; Evans, R.; Kale, A.; Heaven, A.; Clegg, A.; Todd, O. New Horizons in artificial intelligence in the healthcare of older people. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveys, K.; Prina, M.; Axford, C.; Domènec, Ò.R.; Weng, W.; Broadbent, E.; Pujari, S.; Jang, H.; Han, Z.A.; Thiyagarajan, J.A. Artificial intelligence for older people receiving long-term care: A systematic review of acceptability and effectiveness studies. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e286–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kolfschooten, H. The AI cycle of health inequity and digital ageism: Mitigating biases through the EU regulatory framework on medical devices. J. Law Biosci. 2023, 10, lsad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Yang, J.; Lim, S. Emotion Recognition Using Transformers with Random Masking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 4860–4865. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Evaluation and analysis of visual perception using attention-enhanced computation in multimedia affective computing. Front Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1449527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Date | Country | Design | Sample Size | Patients with Neurocognitive Disorder (n) | Age (Mean/Median) | Control | Inclusion Criteria | Tool Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umeda-Kameyama et al., 2021 [26] | Japan | Cohort | 238 | AD: 121 | 80.6 | Healthy: 117 | Patients diagnosed with AD | Facial images |

| Chen et al., 2022 [27] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 23 | AD: 23 | 83.6 | - | Patients diagnosed with AD | Recorded facial videos |

| Fei et al., 2022 [28] | China | Cohort | 61 | MCI: 36 | >65 | Healthy: 25 | Patients with MCI | Recorded facial videos |

| Zheng et al., 2023 [29] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 117 | Dementia: 117 | >65 | - | Patients participating in the PROMPT Dataset | Recorded facial videos |

| Sun et al., 2024 [30] | USA | Cross-sectional | 186 | MCI: 100 | >75 | Healthy: 86 | Patients with MCI | Recorded facial videos |

| Bergamasco et al., 2025 [31] | Italy | Cross-sectional | 60 | MCI: 26 Dementia: 10 | 68.2 | Healthy: 28 | Patients with CI | Recorded facial videos |

| Author/Date | Facial Component | Neurological Disorder | Algorithm Description | Models | Best Performance Model | Percentage of Detection Accuracy | Main Findings | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umeda-Kameyama et al., 2021 [26] | Full face | AD | Xception SENet50 ResNet50 VGG16 simple CNN | Deep learning network | Xception + Adam | 92.5% | Se: 87.52 ± 11.91% Sp: 94.57 ± 10.88% | Xception AI can differentiate facial images of people with mild dementia from those without dementia |

| Chen et al., 2022 [27] | Full face | AD | FERS | Deep learning network | FERS | 86.0% | FERS: 86.0% | FERS-based AI successfully predicted behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia |

| Fei et al., 2022 [28] | Full face | MCI | AlexNet MobileNet + block_11_add + SVM | Deep learning network | MobileNet + block_11_add + SVM | 73.3% | SVM 73.3% KNN: 60.0% | The AI algorithm has good recognition accuracy |

| Zheng et al., 2023 [29] | Full face | Dementia | Face Mesh HOG Action Unit | Traditional machine learning Deep learning | HOG | 79.0% | Face Mesh: 66.0% HOG: 79.0% Action Unit: 71.0% | Computer programs have the potential to be a crucial indicator in the detection of dementia |

| Sun et al., 2024 [30] | Full face | MCI | MC-ViViT | Deep learning network | MC-ViViT | 90.63% | MC-ViViT: 90.63% | AI can detect MCI with promising accuracy |

| Bergamasco et al., 2025 [31] | Full face | MCI Dementia | KNN LR SVM | Machine learning | KNN | 73.6% | MCI vs. HC: 76.0% Dementia vs. HC: 73.6% | AI as a potential facial emotion analyzer and non-invasive tool for the early detection of CI |

| Author/Date | Model Architectures | Specific Models | Dataset Used | Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umeda-Kameyama et al., 2021 [26] | CNN | Xception SENet50 ResNet50 VGG16 simple CNN | Proprietary dataset collected by the researchers | Static facial images |

| Chen et al., 2022 [27] | CNN | FERS | Dataset collected in a day-care center | Facial video recordings |

| Fei et al., 2022 [28] | CNN + ML | AlexNet MobileNet + block_11_add + SVM | Videos collected | Facial video recordings |

| Zheng et al., 2023 [29] | ML | Face Mesh HOG Action Unit | PROMPT dataset | Facial video recordings |

| Sun et al., 2024 [30] | Transformer-based model | MC-ViViT | I-CONECT dataset | Facial video recordings |

| Bergamasco et al., 2025 [31] | ML | KNN LR SVM | Dataset collected at clinical sites | Facial video recordings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Runzer-Colmenares, F.M.; Cahuapaza-Gutierrez, N.L.; Calderon-Hernandez, C.C.; Loret de Mola, C. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Facial Expression Analysis for Mental Health Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Future Internet 2025, 17, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120541

Runzer-Colmenares FM, Cahuapaza-Gutierrez NL, Calderon-Hernandez CC, Loret de Mola C. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Facial Expression Analysis for Mental Health Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRunzer-Colmenares, Fernando M., Nelson Luis Cahuapaza-Gutierrez, Cielo Cinthya Calderon-Hernandez, and Christian Loret de Mola. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Facial Expression Analysis for Mental Health Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120541

APA StyleRunzer-Colmenares, F. M., Cahuapaza-Gutierrez, N. L., Calderon-Hernandez, C. C., & Loret de Mola, C. (2025). Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Facial Expression Analysis for Mental Health Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Future Internet, 17(12), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120541