Abstract

Urban agriculture presents unique challenges, particularly in the context of microclimate monitoring, which is increasingly important in food production. This paper explores the application of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to forecast key sensor measurements from thermal images within this context. This research focuses on using thermal images to forecast sensor measurements of relative air humidity, soil moisture, and light intensity, which are integral to plant health and productivity in urban farming environments. The results indicate a higher accuracy in forecasting relative air humidity and soil moisture levels, with Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPEs) within the range of 10–12%. These findings correlate with the strong dependency of these parameters on thermal patterns, which are effectively extracted by the CNNs. In contrast, the forecasting of light intensity proved to be more challenging, yielding lower accuracy. The reduced performance is likely due to the more complex and variable factors that affect light in urban environments. The insights gained from the higher predictive accuracy for relative air humidity and soil moisture may inform targeted interventions for urban farming practices, while the lower accuracy in light intensity forecasting highlights the need for further research into the integration of additional data sources or hybrid modeling approaches. The conclusion suggests that the integration of these technologies can significantly enhance the predictive maintenance of plant health, leading to more sustainable and efficient urban farming practices. However, the study also acknowledges the challenges in implementing these technologies in urban agricultural models.

1. Introduction

Urban agriculture, the practice of cultivating food in or around urban areas, is gaining momentum as a solution to various challenges including food security [1]. However, maximizing the potential of urban farms requires precise, efficient, and scalable methods for monitoring these complex systems. Here, computer vision and deep learning emerge as powerful tools [2]. By harnessing these technologies, urban agricultural systems can be equipped with predictive analysis capabilities, enabling real-time decision making and optimized resource utilization. The Internet of Things (IoT) in urban agriculture, particularly the use of environmental sensors for plant monitoring, marks a significant stride in the quest for sustainable and efficient urban food production. This research focuses on IoT plant environmental sensors and computer vision and machine learning (ML) technologies to forecast parameters related to plant well-being, a novel approach that promises to revolutionize agricultural practices in urban environments.

Urban agriculture faces the challenge of optimizing plant growth conditions in varied and often constrained urban environments [3]. IoT environmental sensors, capable of monitoring factors like soil moisture, temperature, humidity, and light intensity, have become indispensable in addressing this challenge [4,5]. The integration of computer vision adds a new dimension, enabling the analysis of visual cues from plants to predict their well-being, physiological traits, health, and growth patterns. This synergy is crucial for advancing urban agriculture, ensuring better resource management and enhanced crop yields in urban settings.

The purpose of this research is to investigate the potential of combining IoT environmental sensors with computer vision and ML to accurately forecast plant well-being in urban agricultural systems. This approach is significant as it could lead to more proactive and precise farming practices, allowing for timely interventions to optimize plant health and productivity. It also holds the potential to minimize resource waste and improve the environmental footprint of urban farms.

This manuscript is organized into five sections which are “Related Work and Research Gaps”, and it provides an overview of the existing studies about monitoring in precision agriculture and identifies the current gaps that this research aims to fill. The “Methodology” section explains the methodology used in the research. The “Model Development and Training” section describes how the deep neural network was trained for forecasting sensor measurements from thermal images. The “Results Evaluation and Discussion” section presents the results of the research, evaluating the accuracy of the CNN model in forecasting relative air humidity, soil moisture, and light intensity. The “Conclusions” section summarizes the key findings of the research and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work and Research Gaps

Machine learning and computer vision technologies have demonstrated immense potential in transforming agricultural practices, especially in plant monitoring [6]. These technologies offer advanced capabilities for early detection and prediction of various plant health conditions, which are crucial for sustainable and efficient agricultural practices.

For instance, deep learning algorithms can analyze a vast array of data from different sources, including sensors and imaging equipment used in agriculture. These algorithms, such as logistic regression models, ensemble methods, and decision trees, can reveal hidden patterns and relationships in data. In the context of plant monitoring, this means they can forecast future health conditions of plants by analyzing historical data and current observations. This approach is how machine learning aids in early health prediction in healthcare, as it helps in identifying risks early, so it is possible to take preemptive actions to mitigate health problems [7].

Similarly, computer vision, particularly using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), plays a pivotal role in agriculture [8,9]. CNNs can be particularly effective in processing and interpreting vast quantities of visual data from plants. They excel in tasks such as detecting signs of disease, nutrient deficiencies, or pest infestations by analyzing images of plant leaves and fruits [8]. Neural networks can enhance this by processing sequential data, making them suitable for analyzing temporal changes in plant conditions. This is analogous to their use in healthcare for analyzing medical images and time series data for early disease detection [7]. Combining these technologies, farmers and agriculturalists can make informed decisions, leading to improved crop health and yield, while also conserving resources.

In the domain of IoT based plant monitoring in agriculture, deep learning can play a pivotal role, particularly in the analysis of plant data, which involves several steps. The initial step was to preprocess the data, which is essential to detect potential outliers, identify redundancies, and generate data for the training, validation, and testing of the machine learning algorithm. In a practical scenario, measurements from sensors can be combined with manually recorded data to create an augmented dataset. To ensure the quality and relevance of this dataset, approaches such as removing or not taking sensor measurements during certain periods (for example, at nighttime, in the case of indoor occupancy detection) can be applied to avoid bias due to unrepresentative data samples [10]. This approach results in a data set encompassing various parameters, such as temperature, humidity, light intensity, and CO2 levels, which are crucial for analyzing plant health and environmental conditions [8].

The next step involves analyzing the relationships between different parameters in the dataset. For instance, in the case of indoor occupancy detection, a correlation analysis revealed that certain measurements, like CO2 and Total Volatile Organic Compounds (TVOC), exhibited a strong correlation, indicating that one of these attributes could be eliminated without impacting the performance of the algorithm [10]. This type of analysis is crucial in plant monitoring as well, where factors such as temperature, relative humidity, and light intensity might exhibit dependencies. Understanding these relationships is vital for reducing the complexity of the model and focusing on the most impactful parameters for plant health analysis.

Finally, a suitable deep learning algorithm can be selected to process and learn from the data. In the case of occupancy detection [10], a two-layer feedforward neural network (FNN) with sigmoid output neurons was used. The choice of such a network is motivated by its ability to learn and model various types of relationships, including non-linear and complex ones. In agricultural plant monitoring, selecting the right algorithm is key to understand plant data from sensor networks. This data can show complex patterns influenced by environmental factors like soil moisture, relative humidity, and temperature, which are important for making more informed farming decisions.

The research in [11] provides insights into the application of deep learning and computer vision in forecasting plant well-being in agriculture. The research focuses on using image processing and deep learning techniques to classify nutrient deficiencies in black gram plants, a methodology that can be extended to other crops for monitoring their health and predicting future well-being. Images of black gram plants grown under controlled conditions were used with specific nutrient treatments. Images were taken daily for 28 days, capturing both young and old leaves. However, not all days were represented due to issues like leaf maturity and lighting. To address the challenge of capturing the entire plant in a single image, the researchers combined images of old and young leaves. This approach not only enriched the data but also highlighted the importance of considering different plant parts in assessing overall health. They also used data augmentation techniques like horizontal flipping and scaling to expand the dataset, ensuring a robust model training process.

The research in [11] utilized pre-trained deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for feature extraction from the images. The use of a pre-trained model, such as ResNet50, allowed for efficient processing and learning from the images without the need for extensive computational resources. This approach demonstrates the effectiveness of leveraging existing models and adapting them for specific agricultural applications. The extracted features provide crucial information about the plant’s health, enabling the detection of nutrient deficiencies that can affect the plant’s well-being.

For classification, the study employed techniques like multiclass logistic regression (MLR), support vector machine (SVM), and multilayer perceptron (MLP). These classifiers compared the performance in identifying various nutrient deficiencies, showing that deep learning models can effectively categorize different health states of plants based on visual cues. This classification capability is key to forecasting plant well-being, as it allows for the early detection of potential issues and timely intervention. For example, identifying a nitrogen deficiency early can lead to prompt fertilization, preventing yield loss and maintaining plant health.

The research in [12] presents an approach in plant monitoring that can be applied in urban agriculture environments. It focuses on using infrared thermal imaging technology and a novel three-dimensional temperature (3D-3T) model for estimating canopy transpiration rates in plants, specifically citrus trees. This approach holds promise for enhancing plant monitoring and water management in urban agricultural settings. The research utilizes infrared thermal imaging to accurately measure the average temperature of plant canopies. This technology is key for urban agriculture, where environmental monitoring is crucial yet challenging due to the complex urban microclimates. By accurately capturing canopy temperatures, this method provides vital data for understanding plant water needs and stress levels, which are critical for optimizing irrigation and ensuring plant health in urban settings. The results presented in [12] accounts for the additional energy provided by solar radiation from different directions, a factor particularly relevant in urban environments where shading and light exposure can vary significantly due to buildings and other structures. The model’s ability to estimate transpiration rates accurately, as validated by comparisons with sap flow measurements, makes it a useful tool for monitoring and managing water use in urban agriculture.

The techniques developed in this study can be suited for urban agriculture, where space is limited, and plants may be grown in non-traditional settings such as rooftops, balconies, and indoor gardens. The non-contact and non-invasive nature of thermal imaging aligns with the need for minimal disturbance in such environments. Furthermore, the model’s reliance on easily obtainable input factors like leaf temperature and solar radiation makes it accessible for urban farmers who might not have extensive technical resources.

Traditional methods for estimating transpiration rates often face challenges in urban environments due to the difficulty in obtaining or calculating parameters like aerodynamic resistance and canopy resistance. The 3D-3T model’s advantage lies in its independence from these complex parameters, making it a straightforward and potentially more accurate method for urban plant monitoring.

In plant monitoring and agricultural technology, there has been considerable progress in developing specialized methods for specific aspects of plant health assessment. However, a notable gap in the current research is the lack of integration between different domains, particularly in the fusion of computer vision techniques with sensor data monitoring for comprehensive plant health forecasting.

The studies that were reviewed were advanced in their respective areas, but they are isolated from one another. For instance, research that was utilizing infrared thermal imaging and the 3D-3T model focuses primarily on estimating canopy transpiration rates in plants [12]. This approach, though innovative in its use of thermal imaging, does not incorporate other vital sensor data that could offer a more holistic view of plant health.

Similarly, the study on black gram plant nutrient deficiency classification using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in [11] demonstrates the potential of computer vision in identifying specific nutrient deficiencies through image analysis. However, this research does not extend to the integration of sensor data which could provide additional context such as soil moisture levels, nutrient concentrations, or environmental conditions that are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of plant health.

Another study, related to the utilization of CNN based regression models, has proven to be an effective approach for estimating correlated color temperature (CCT) from RGB images [13]. CNN, which are variants of multilayer perceptrons, mimic the functionality of the human visual cortex and are well suited for image processing tasks. The adaptability of CNNs have been proven in study [13] to handle large scale image datasets, delivering results that confirm their capability in processing not only static two-dimensional images but also dynamic three-dimensional video data. This attribute of CNNs, when used in a plant monitoring domain for thermal imagery use cases, indicates a promising approach for accurately forecasting plant health indicators by interpreting the thermal patterns that are indicative of a plant physiological state.

The research presented in [14] describes the integration of infrared thermography (IRT) in the assessment of soil moisture content, demonstrating a non-destructive and non-contact method that holds promise for advanced plant monitoring systems. Through the application of an external halogen lamp light and capturing soil surface temperatures with an infrared camera, the study achieved a high correlation between thermal data and soil moisture content. This technique’s successful estimation of moisture content highlights the potential of IRT to serve as a valuable tool in precision agriculture, providing a means to monitor soil conditions closely without physically altering the soil environment.

Furthermore, the relationship between the soil’s surface temperature and its moisture content was established with a high degree of accuracy, showcasing a clear inverse correlation—as the moisture content decreased, the temperature rose, and vice versa. This finding is pivotal for plant monitoring, as it underscores the feasibility of using thermal data to infer critical environmental parameters that affect plant health, such as soil moisture. The ability to derive such parameters from thermal images could enable the development of advanced machine learning models, including CNNs, to forecast different types of plant monitoring sensor measurements.

Similarly, the study [15] provides advancements for urban agriculture by employing thermal imaging to gauge water stress in citrus plants, a technique that could be used for plant monitoring in densely populated areas where plant growing spaces are limited. By directly examining plant canopy temperatures in a controlled greenhouse environment, researchers were able to detect the water status of one-year-old citrus plants, detecting water stress through variations in canopy temperature [15]. This noninvasive method showcased a strong correlation between irrigation levels and plant temperature responses, with thermal cameras efficiently showing plants under a water deficit by identifying higher canopy temperatures compared to ambient air. The research underpins the utility of thermal data as a reliable metric for plant monitoring, suggesting that such techniques, when integrated with automated systems, could significantly enhance irrigation scheduling in urban agricultural practices [15]. This approach has the potential to optimize water use and ensure plant health in urban environments, where efficient resource management is crucial.

Regarding the deep neural network architecture in this context, papers [16,17] demonstrate how CNN architectures can be used in extracting complex features from images for forecasting. The study [16] illustrates how CNNs can estimate tropical cyclone intensity from satellite imagery by interpreting visual data for weather analysis. The paper [17] extends this capability to “El Niño” forecasting, by analyzing spatial patterns in climate data. These studies describe the potential of CNNs in models designed for regression tasks, where single output values are forecasted from image data, by correlating visual patterns with specific sensor measurement values.

Unfortunately, the absence of a unified approach that combines the strengths of both computer vision and sensor data monitoring and analysis is a significant limitation in the current research in this area. Current methodologies focus on singular aspects of plant health, such as nutrient deficiencies or transpiration rates, without exploring the potential connections that could arise from a combined analysis of visual data and sensor readings. This approach results in a fragmented understanding of plant health, where each method provides insights into specific aspects without offering a comprehensive overview.

A more integrated approach, where computer vision applications are used in combination with sensor data monitoring, could revolutionize plant health forecasting. By combining the detailed visual analysis possible through computer vision techniques with the data provided by sensors, including thermal imagery, researchers could develop models capable of forecasting multiple sensor reading values from related sensors and parameters. This would not only enhance the accuracy of plant health assessments but also enable the forecasting of various plant health outcomes, leading to a more effective plant growth process.

3. Methodology

To explore the identified research gaps in forecasting sensor measurements in urban agriculture environments, a novel method is proposed and evaluated in a plant monitoring setup where strawberry plants are grown and monitored. The proposed sensor measurement forecasting method involves capturing and processing images from a thermal camera, then using these thermal images as input to machine learning model for nearby sensor measurement forecasting, for example, light intensity, soil water content, and relative humidity.

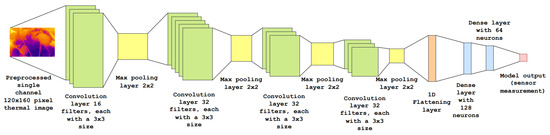

Informed by the successful forecasting methodologies demonstrated in the two discussed papers [16,17], a novel model is conceptualized. The proposed architecture (Figure 1) employs a 120 × 160 temperature pixel array from thermal images as its primary input, adapting this data for use in a regression model framework. The thermal image (2D array of temperature values) will be preprocessed prior to being used. Colored images are rendered using the default colormap of the camera module software, which is employed to visualize thermal imagery, offering a more distinct representation of the data. However, these colored images are not used during the model training.

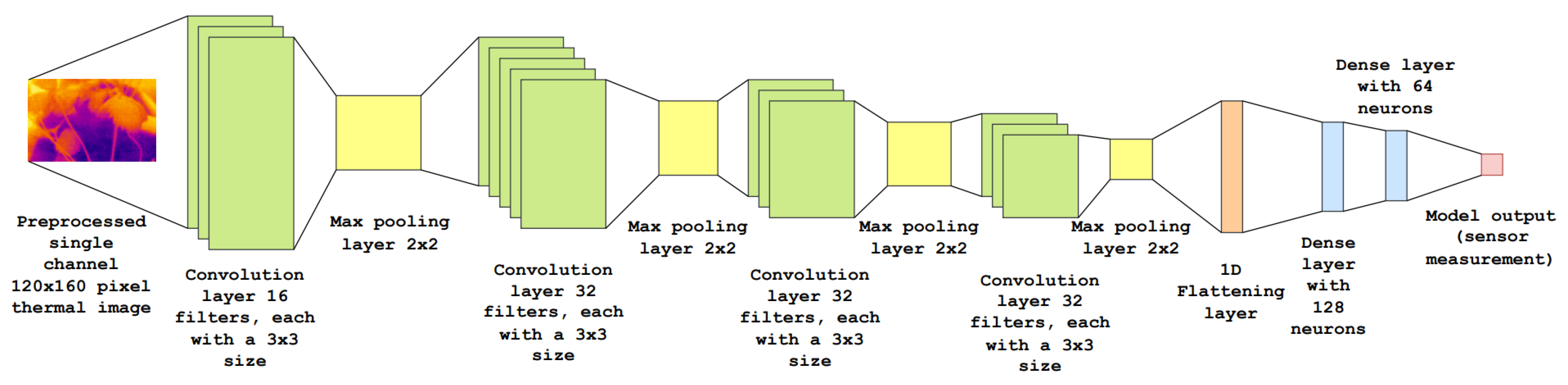

Figure 1.

Scheme of proposed model architecture for sensor measurement forecasting.

The model is engineered to leverage the efficiency of convolutional neural network architectures in the processing and analysis of image data, aiming to enhance the precision in forecasting sensor measurement data. As output, the trained model gives a sensor reading at the same date time when the thermal image was taken.

The proposed multilayer CNN architecture is an adjustment from “VGGnet” [18]-type architectures. It is designed for image analysis with an emphasis on extracting a singular continuous output from visual data. The network begins with an input layer that accepts a 120 × 160 pixel image. This input is then processed through a sequence of convolutional layers, where each layer is equipped with numerous filters to detect various features. These filters generate multiple feature maps, increasing the depth of the network.

The first convolutional layer reduces the image size, and each subsequent convolutional layer is followed with a max-pooling layer, which further downsizes the spatial dimensions. Max-pooling is a common technique used to reduce the spatial size of the representation to decrease the number of parameters and computation in the network, to also control the overfitting [19].

The convolutional layers, through their hierarchical structure, are designed to capture progressively higher-level features of the input image. This process begins with simple edges and textures, progresses through complex patterns, and parts of objects, and ends by resulting in high-level features that compactly represent the input image.

After the last convolutional and max-pooling layer, the data are flattened into a one-dimensional array, which is a common practice before passing the data to the next layers. The architecture then includes a dense layer, which integrates the features extracted by the convolutional layers. This is followed by two more fully connected layers with 128 and 64 neurons, which continue to refine the data for the final output. The last layer is a single neuron to output a single measurement for a sensor, for example, in this study, light intensity, relative air humidity, or soil water content. The proposed CNN regression model could be particularly useful in precision agriculture for monitoring crop conditions by providing multiple continuous sensor measurements from non-contact thermal image data, with an aim to extract as much environmental information as possible only from the thermal images.

Also, possibilities to obtain more than one sensor reading from a single thermal image or obtaining one sensor reading from multiple historical thermal images remains, given the close alignment in timing between the collection of environmental sensor data and the capturing of a thermal image used as input to the given model.

4. Model Development and Training

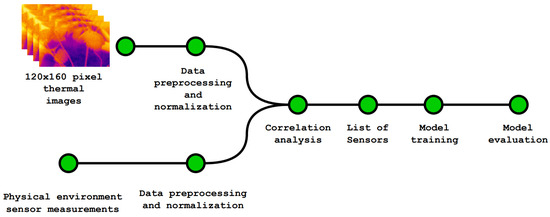

A deep learning and computer vision model to forecast strawberry plant environmental sensor measurements was developed using data collected from various sensors during a 2-month period—July and August of the year 2023. The sensors used in model development were a FLIR Lepton 3.5 radiometric thermal camera [20], BH1750 light sensor [21], DHT11 temperature and humidity sensors [21,22], and a soil water content sensor [23]. The development process included several stages like data gathering, preprocessing, model development, tuning, and validation (Figure 2).

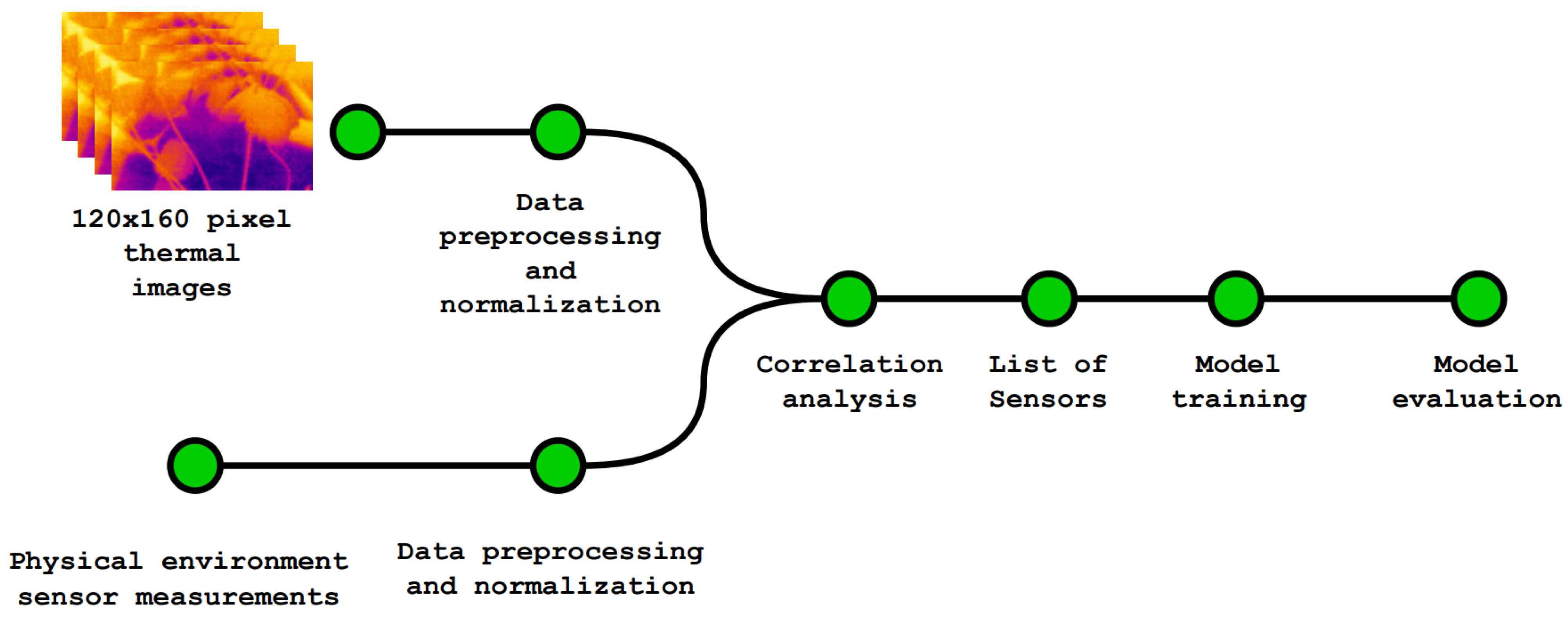

Figure 2.

The process of model training.

4.1. Data Gathering

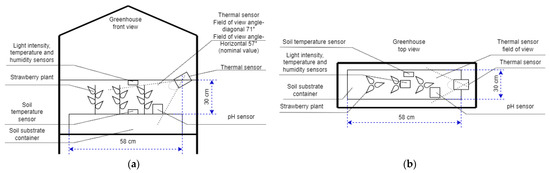

- Thermal Camera (Flir Lepton 3.5): Captured images of strawberry plants at 15 min intervals (Figure 3). Each image was saved as an array of size 120 × 160 (which matches the camera resolution) in a CSV file format. Each pixel measurement has a precision of 0.05 °C and can measure temperatures between −40 °C and +400 °C. This approach provided a comprehensive dataset capturing the temperature variations of the plants.

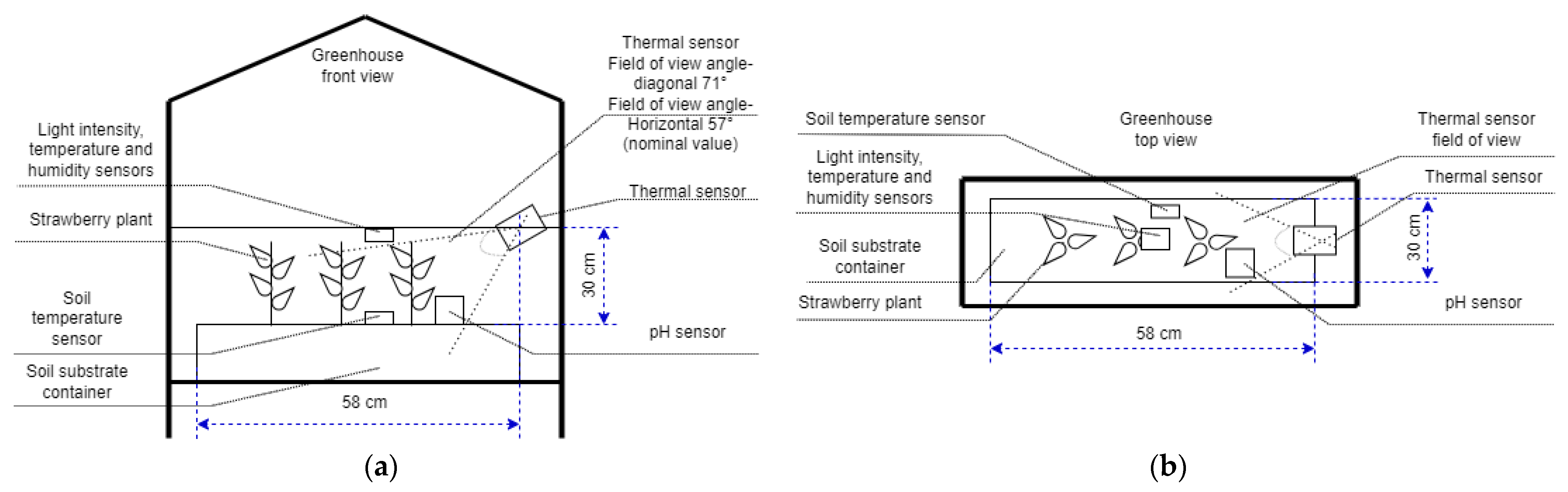

Figure 3. Data gathering location and spatial characteristics: (a) Front view of the greenhouse and (b) top-down view of the greenhouse.

Figure 3. Data gathering location and spatial characteristics: (a) Front view of the greenhouse and (b) top-down view of the greenhouse. - Light Sensor (BH1750): Measured the intensity of light in the plant environment (with accuracy of ±20% and measurement range of 0.11–65,535 lux). The collected light intensity data were crucial for understanding the photosynthetic activity and growth patterns of the strawberry plants.

- Temperature and Humidity Sensor (DHT11): Provided ambient temperature (with accuracy of ±2 °C and measurement range of 0–50 °C) and relative humidity data (with accuracy of ±5% RH and measurement range of 0–100% RH). This information was essential for understanding the microclimate conditions surrounding the strawberry plants.

- Capacitive Soil Water Content Sensor: Collected analog value data (with accuracy of ±2% measurement range of 0–100% RH) on the soil moisture levels, a critical factor affecting plant growth and nutrient uptake.

A total of 1072 thermal images and 2220 sensor measurements were gathered and used in further data preprocessing and model training. Also, an attempt to use other sensors (pH and soil temperature seen in Figure 3) did not produce usable and valid data during the specified time, so they were not included in the final model development. Only values that had matching timestamps in both datasets were used in the corresponding model training.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

In the process of monitoring sensor and thermal image data, there are instances when data may be missing and create some gaps due to various reasons, for example, sensor malfunctions, data transmission problems, and others, that are not explored in this article. These gaps can lead to inaccuracies in forecasting results if not properly addressed before training the model. Due to this, in both the sensor data and thermal images, it was decided to group the sensor measurements by hourly mean. This approach allowed for a more consistent and reliable dataset, compensating for the missing data points that can improve the model forecasting capabilities.

The sensor data were loaded, and the time column was converted to datetime format, enabling it to be set as the “DataFrame” index. This allowed the resampling of the data to an hourly mean. The processed data were then converted into a dictionary format and saved as a file, ensuring effective retrieval for model implementation. Similarly, the preprocessing of thermal image data involved parsing timestamps from filenames in a specified directory and organizing the data by hourly averages. Each image file, stored as a CSV, was read, and its data were aggregated based on the parsed hourly timestamp. This approach allowed for the calculation of mean values for each hour by stacking the matrices from the same time and averaging them. The processed data, now represented as mean matrices for each timestamp, was then saved in a dictionary that was used for model training.

Data from each sensor were preprocessed to address issues such as missing values and inconsistencies. The thermal images along with sensor reading values were normalized using min-max normalization [24] to ensure uniformity in scales across all images and readings before they are used in the model for sensor measurement forecasting.

4.3. Data Pre-Analysis

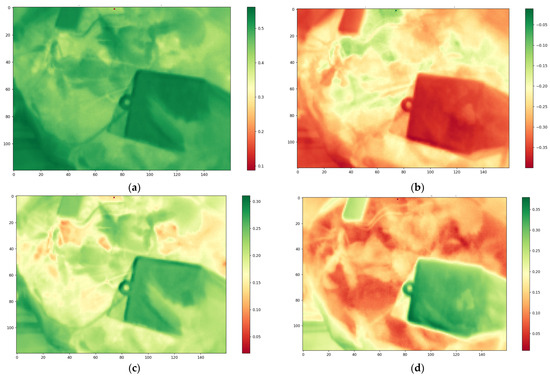

Given that the gathered thermal data had a time series characteristic (each thermal image was gathered every 15 min) similarly to other sensor measurements, it was decided to investigate potential relationships between model input (thermal images) and output (temperature, humidity, soil water content, light intensity sensor) data. To analyze this relation, it was decided that before the model development, a data correlation analysis needs to be performed. This analysis evaluated how each pixel in all the thermal images correlated with readings from the other sensors (light sensor, temperature and humidity sensor, and soil sensor) over the two-month data collection period. This step was to understand the relationships between the surface temperatures of the plants, as captured by the thermal camera, and the environmental conditions measured by the other nearby sensors. It helped in identifying patterns and dependencies that could be useful when choosing the model input parameters and training the model. The correlation analysis results (Figure 4) confirmed that thermal images correlate well with nearby air temperature sensors, which was used as a reference. Figure 4 presents a series of correlation heatmaps, showing the relationship between pixel values over a 2-month period and various sensor readings. The axes of each heatmap correspond to the coordinates of individual pixels within a 120 × 160 array, representing the image size.

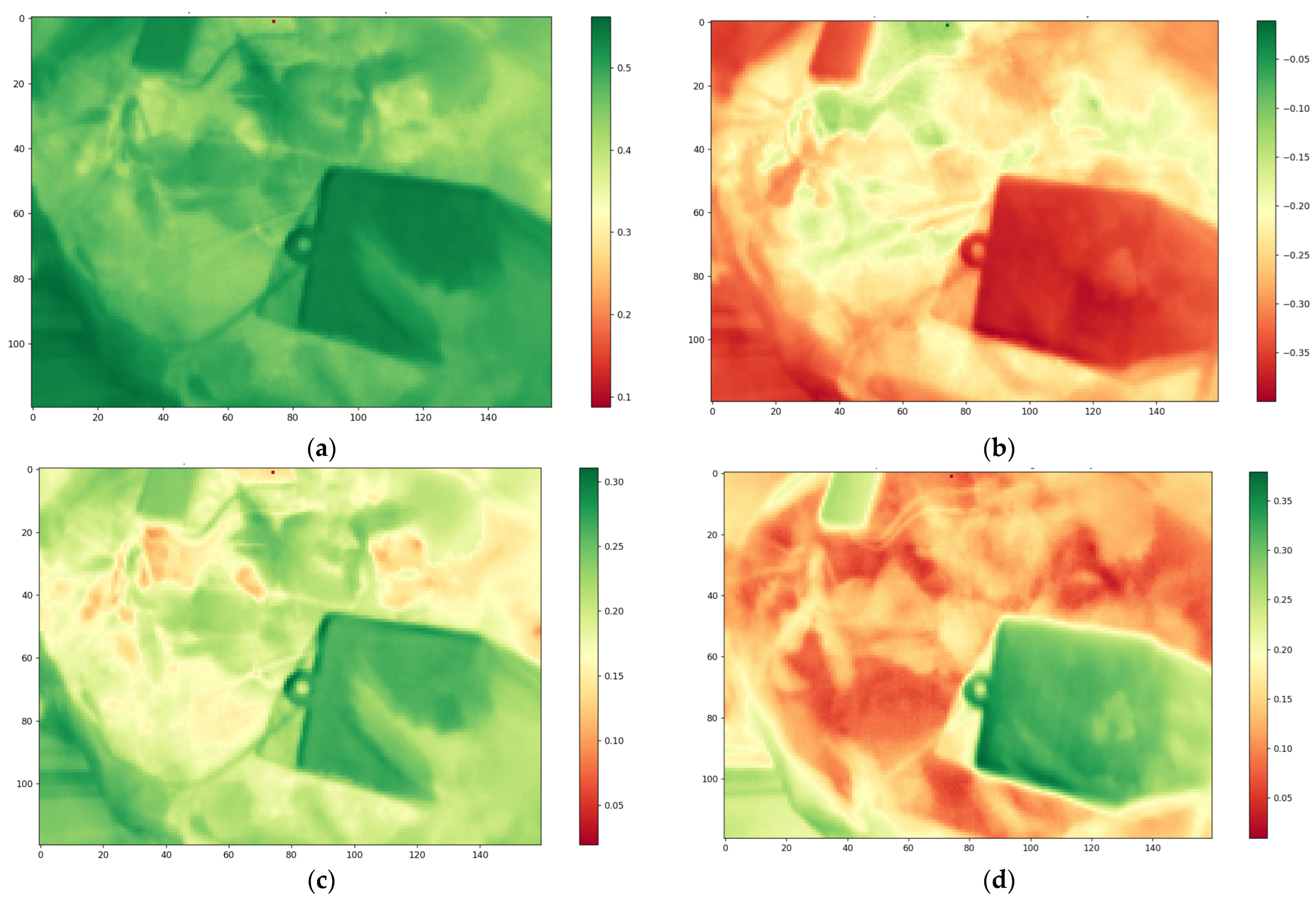

Figure 4.

Different sensor correlations with thermal image pixels during all data gathering period. Correlation heatmap between pixel values and (a) air temperature sensor data; (b) air humidity sensor data; (c) soil water content sensor data; (d) light intensity sensor data.

For instance, in Figure 4a, the pixel located at vertical pixel location 0 and horizontal pixel location 0 (X = 0; Y = 0) appears within a darker region, indicating a relatively high correlation with the air temperature sensor, as compared to other pixels in the image. This is supported by a correlation coefficient exceeding 0.5, as can be seen in the adjacent scale. It is important to note that these heatmaps contain a correlation analysis over a two-month period, comparing pixel values against the corresponding time series data of air temperature, relative humidity, soil water content, and light intensity recorded concurrently.

It was determined that the light intensity correlated the least with thermal image data, although nearby surfaces, such as sensor casings, gave an indication that there is some amount of correlation visible.

4.4. Model Development

After evaluating the correlation between each sensor (air humidity, soil water content, and light intensity) readings and the pixel values of thermal images, a separate model for each of the mentioned sensors was implemented. In this paper, CNN was used for the proposed sensor forecast model development due to its known capabilities in both the image data classification and regression tasks discussed in the literature review. CNNs are useful for automatically detecting and learning spatial hierarchies of features from images, which was useful for the interpretation of thermal images where temperature patterns and other parameters can be indicative of plant health or other surrounding environmental conditions.

The proposed model was implemented using “Tensorflow” library [25]. The model contains convolutional layers to extract high-level features from the thermal images, pooling layers to reduce the dimensionality of the data, and fully connected layers to interpret these features. While a CNN is often used to process images, in this case, it was used to forecast a single sensor measurement for the same datetime used in the model input. Therefore, it was required to include a dense layer with a single neuron as model output—single sensor measurement. The dataset was divided so that 60% was used for the training phase and an additional 20% of the data were designated for validation purposes, used for hyperparameter tuning, in total using 80% of the data available. The remaining 20% of the dataset were used for model testing.

4.5. Model Initial Tests and Adjustments

By using the proposed CNN model architecture, in total, three different models were implemented and trained for light intensity, air humidity, and soil water content sensor measurement forecasting (Table 1). Each model utilizes a thermal image matrix of 120 × 160 as its input. Model #1 is designed to forecast light intensity, measured in lux. Model #2 focuses on forecasting air humidity percentages. Lastly, Model #3 is for forecasting soil water content, with an output range from 0 to 4095 (which is a sensor value output), where 0 corresponds to the highest water content and 4095 to the lowest.

Table 1.

Models used in sensor measurement forecasting.

Additionally, to optimize each CNN model for forecasting sensor measurements from plant thermal images, hyperparameters such as filter sizes in convolutional layers, learning rates, and numbers of neurons in dense layers can be used [26,27]. In this case, batch size, epochs, and learning rate parameters were used. The optimization aim was to enhance each model’s ability to accurately analyze patterns in thermal images, resulting in more precise sensor measurement forecasts. One of the hyperparameter optimization approaches is to use “Grid Search” [28]. It systematically builds and evaluates a model for each combination of parameters specified in a grid. While effective for models with a limited number of hyperparameters, Grid Search can be computationally intensive, especially for larger, more complex models. This search over specified parameter values aims to find the best combination that maximizes the performance of the model [28]. As a result, the following parameters were used in model training and evaluation (see Training Parameters in Table 1).

Training for each model was performed 30 times with the optimal training parameters to ensure that the results are consistent between the runs.

5. Results Evaluation and Discussion

The evaluation of the regression models was based on different metrics, such as MAPE, MAE, MSE, RMSE, and R2, that are commonly used for regression model evaluation [29,30]. The results (Table 2) showed that the most accurate model based on MAPE was model #3, which forecasted soil water content sensor measurements.

Table 2.

Average results for each model in sensor measurement forecasting.

Model #1, which forecasted light sensor measurements, appears to have significant forecast errors, with an MAE of 332.38 and an RMSE of 781.05 for the given scale, and an MAPE exceeding 100%, indicating poor forecasting accuracy. Additionally, it was explored how this model results could be improved by incorporating memory-based time series model LSTM along with CNN model making a hybrid CNN-LSTM model [31]. The paper suggested that it could be possible to train a model by using multiple images as input, leading to the sensor measurement value that needs to be forecasted. After some experimentation it was concluded that the light intensity measurement forecast result did not improve by using this type of model. That may suggest that the thermal data need some additional parameters to be able to forecast light intensity measurements. For example, parameters like distance to windows and number of windows, in a room where plants are grown, would be just some of those that could potentially increase the forecasted measurement accuracy [32]. Another study suggests that regarding lighting estimations, a detailed representation of the physical and optical characteristics of a surface needs to be considered as a measurement forecasting model inputs [33].

Model #2, which forecasted air humidity, showed comparatively higher performance with an MAPE of 11.22%, MAE of 4.35, and RMSE of 7.09, suggesting high accuracy in its forecasts. This result matches with the other studies and correlations in this study where air humidity has an inverse correlation with air temperature. This suggests that air humidity sensor measurements can be forecasted with the given accuracy.

Model #3, which forecasts soil water content, has a similar result as model #2 performance with an MAPE of 10.35%, which is slightly lower. Also, an R2 value of 0.633 for model #3 suggests that this model is a potentially better fit for the data it was trained on resulting in the highest accuracy of all models.

Although the MAPEs for model #2 and model #3 are similar, there are differences in MAE and RMSE values, which are comparatively higher for model #3. The differences are due to the different scales that are used for each sensor.

This study’s primary contribution lies in its approach to forecasting various environmental parameters crucial for urban agriculture, specifically light sensor measurements, air humidity, and soil water content, using deep learning models that can be also deployed on resource-constrained IoT devices which are commonly used throughout agriculture. The model #1 challenges in accurately forecasting light sensor measurements underline the complexity of capturing light intensity dynamics using only thermal data imagery. This insight is an addition to the field, as it directs future research towards considering additional parameters like spatial factors, reflections, or others for light forecasting. A comparative analysis of these models, particularly in terms of MAE and RMSE, provides critical insights into the varying challenges and considerations when modeling different environmental parameters. The models could be used as a basis for future models to further expand the knowledge about sensor measurement forecasting from image data. The results can also be used for future research to explore alternative measurement options in environments where physical sensors cannot be installed.

6. Conclusions

In urban food growing areas, the setup where a single thermal camera is used could potentially be more effective than deploying multiple sensors, especially where the growing space is limited. However, this approach may have limitations in capturing the diverse range of data typically gathered by a variety of physical sensors. While deploying a single image sensor instead of many physical sensors has the potential to reduce the maintenance cost and overall expense of plant monitoring, it is important to note that the effectiveness of a single thermal camera in accurately and comprehensively monitoring plant health has not yet been fully established given that it could be a single point of trust. The quality of data obtained from one sensor type versus multiple sensors needs further exploration to ensure that the data can be trusted, and yield maximization is not compromised.

Given the potential to forecast other measurements for sensors that are measuring plant vital signs, continuing this research with similar experiments and with different sensors is potentially valuable. However, the scope and accuracy of these forecasts, particularly in different environmental conditions and plant types, remain to be thoroughly tested and verified.

Future research could also benefit from a more targeted approach in the application of thermal imaging. Focusing on specific areas of thermal images and using segmentation methods to concentrate on a particular part of the image or a specific plant could potentially result in more precise sensor measurement forecasts.

Furthermore, exploring advanced technologies like Vision Transformers (ViT) in the context of plant monitoring could potentially offer new insights into sensor measurement forecasting. Given a diverse and rich dataset, ViT has shown promising results in various fields of image analysis, but adapting it to the specific needs and challenges of environment monitoring in urban agriculture would require more research and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and I.P.; methodology, A.K. and I.P.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K.; investigation, A.K. and I.P.; resources, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, I.P., A.R., and A.P.; project administration, A.R. and A.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: CNN: Convolutional neural network; MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error; MAE: Mean Absolute Error; MSE: Mean Squared Error; RMSE: Root Mean Squared Error; R2: Coefficient of Determination; LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory; IoT: Internet of Things.

References

- Juárez, K.R.C.; Agudelo, L.B. Towards the development of homemade urban agriculture products using the internet of things: A scalable and low-cost solution. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd Sustainable Cities Latin America Conference (SCLA), Medellin, Colombia, 25–27 August 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharani Pavithra, P.; Baranidharan, B. An analysis on application of deep learning techniques for precision agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 September 2021; pp. 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, K.; Ng, S. Smart planter: A controlled environment agriculture system prioritizing usability for urban home owner. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Robotics and Computer Vision (ICRCV), Beijing, China, 6–8 August 2021; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleefah, R.M.; Al-Isawi, N.A.M.; Hussein, M.K.; Alduais, N.A.M. Optimizing IoT data transmission in smart agriculture: A comparative study of reduction techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Istanbul, Turkiye, 8–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudholkar, M.; Mudholkar, P.; Dornadula, V.H.R.; Sreenivasulu, K.; Joshi, K.; Pant, B. A novel approach to IoT based plant health monitoring system in smart agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Uttar Pradesh, India, 14–16 December 2022; pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, T.; Raza, D.M.; Islam, M.; Victor, D.B.; Arif, A.I. Applications of computer vision and machine learning in agriculture: A state-of-the-art glimpse. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovative Trends in Information Technology (ICITIIT), Kottayam, India, 12–13 February 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badidi, E. Edge AI for Early Detection of Chronic Diseases and the Spread of Infectious Diseases: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Future Internet 2023, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempelis, A.; Romanovs, A.; Patlins, A. Using computer vision and machine learning based methods for plant monitoring in agriculture: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 2022 63rd International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University (ITMS), Riga, Latvia, 6–7 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, W.; Han, H.; He, M.; Gu, W. Satellite internet of things for smart agriculture applications: A case study of computer vision. In Proceedings of the 2023 20th Annual IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Communication, and Networking (SECON), Madrid, Spain, 11–14 September 2023; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, R.; Rodriguez, I.; Razzaghpour, M.; Berardinelli, G.; Christensen, P.H.; Mogensen, P.E. Indoor occupancy detection and estimation using machine learning and measurements from an IoT LoRa-based monitoring system. In Proceedings of the 2019 Global IoT Summit (GIoTS), Aarhus, Denmark, 17–21 June 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.A.M.; Watchareeruetai, U. Black gram plant nutrient deficiency classification in combined images using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 4–6 March 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Dong, X.; Wu, Z.; Wei, C.; Li, L.; Yu, D.; Fan, X.; Ma, Y. Using infrared thermal imaging technology to estimate the transpiration rate of citrus trees and evaluate plant water status. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615 Pt A, 128671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalbas, M.C.; Kobav, M.B. Measurement of correlated color temperature from RGB images by deep regression model. Measurement 2022, 195, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutawa, N.; Eid, W. Soil moisture content estimation using active infrared thermography technique: An exploratory laboratory study. Kuwait J. Sci. 2023, 50, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.H.S.; Ferrarezi, R.S. Use of Thermal Imaging to Assess Water Status in Citrus Plants in Greenhouses. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskey, M.; Ramachandran, R.; Ramasubramanian, M.; Gurung, I.; Freitag, B.; Kaulfus, A.; Bollinger, D.; Cecil, D.J.; Miller, J. Deepti: Deep-Learning-Based Tropical Cyclone Intensity Estimation System. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 4271–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.-G.; Kim, J.-H.; Luo, J.-J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 2019, 573, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrapu, R.R.; Pal, C.; Nimbekar, A.T.; Acharyya, A. SqueezeVGGNet: A methodology for designing low complexity VGG architecture for resource constraint edge applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 20th IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 9–22 June 2022; pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirthika, R.; Manivannan, S.; Ramanan, A. An experimental study on convolutional neural network-based pooling techniques for the classification of HEp-2 cell images. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Information and Automation for Sustainability (ICIAfS), Negambo, Sri Lanka, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-T. Development of a Low Cost and Raspberry-based Thermal Imaging System for Monitoring Human Body Temperature. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th International Microsystems, Packaging, Assembly and Circuits Technology Conference (IMPACT), Taipei, Taiwan, 21–23 December 2021; pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, A.L.; Suseno, J.E.; Soesanto, Q.M.B. Measurement Device of Nondestructive Testing (NDT) of Metanil Yellow Dye Waste Concentration Using Artificial Neural Network Based on Microcontroller. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2022, 6, 7500804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, V.; Balambica, V. IoT based agriculture robot using neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 12–13 May 2023; pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi; Murtiningrum; Ngadisih; Muzdrikah, F.S.; Nuha, M.S.; Rizqi, F.A. Calibration of capacitive soil moisture sensor (SKU:SEN0193). In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 7–8 August 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraisha, S.; Shidik, G.F. Evaluation of normalization in fake fingerprint detection with heterogeneous sensor. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication, Semarang, Indonesia, 21–22 September 2018; pp. 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, N.A.A.; Zaid, A.M.; Saon, S.; Mahamad, A.K.; Bin Ahmadon, M.A.; Yamaguchi, S. Malaysian food recognition and calories estimation using CNN with TensorFlow. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 12th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), Nara, Japan, 10–13 October 2023; pp. 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaff, A.K.; Prasetiyo, B. Hyperparameter Optimization on CNN Using Hyperband on Tomato Leaf Disease Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Computational Intelligence (CyberneticsCom), Malang, Indonesia, 16–18 June 2022; pp. 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Cai, Z.; Tang, X.; Yang, Y. CNN hyperparameter optimization based on CNN visualization and perception hash algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 19th International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications for Business Engineering and Science (DCABES), Xuzhou, China, 16–19 October 2020; pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhopipah, A.; Larasati, N.A. CNN Hyperparameter Optimization using Random Grid Coarse-to-fine Search for Face Classification. Kinet. Game Technol. Inf. Syst. Comput. Netw. Comput. Electron. Control. 2021, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachimi, C.; Belaqziz, S.; Khabba, S.; Chehbouni, A. Towards precision agriculture in Morocco: A machine learning approach for recommending crops and forecasting weather. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Digital Age & Technological Advances for Sustainable Development (ICDATA), Marrakech, Morocco, 29–30 June 2021; pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempelis, A.; Narigina, M.; Osadcijs, E.; Patlins, A.; Romanovs, A. machine learning-based sensor data forecasting for precision evaluation of environmental sensing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 10th Jubilee Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (AIEEE), Vilnius, Lithuania, 27–29 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P.; Huang, H.; Lin, E. A CNN-LSTM-att hybrid model for classification and evaluation of growth status under drought and heat stress in chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata). Plant Methods 2023, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanasmaz, T.; Günaydin, M.; Binol, S. Artificial neural networks to predict daylight illuminance in office buildings. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell, M.; Castilla, M.; Rodríguez, F.; Berenguel, M. An indoor illuminance prediction model based on neural networks for visual comfort and energy efficiency optimization purposes. In International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).