Abstract

Online users are responsible for protecting their online privacy themselves: the mantra is custodiat te (protect yourself). Even so, there is a great deal of evidence pointing to the fact that online users generally do not act to preserve the privacy of their personal information, consequently disclosing more than they ought to and unwisely divulging sensitive information. Such self-disclosure has many negative consequences, including the invasion of privacy and identity theft. This often points to a need for more knowledge and awareness but does not explain why even knowledgeable users fail to preserve their privacy. One explanation for this phenomenon may be attributed to online privacy fatigue. Given the importance of online privacy and the lack of integrative online privacy fatigue research, this scoping review aims to provide researchers with an understanding of online privacy fatigue, its antecedents and outcomes, as well as a critical analysis of the methodological approaches used. A scoping review based on the PRISMA-ScR checklist was conducted. Only empirical studies focusing on online privacy were included, with nontechnological studies being excluded. All studies had to be written in English. A search strategy encompassing six electronic databases resulted in eighteen eligible studies, and a backward search of the references resulted in an additional five publications. Of the 23 studies, the majority were quantitative (74%), with fewer than half being theory driven (48%). Privacy fatigue was mainly conceptualized as a loss of control (74% of studies). Five categories of privacy fatigue antecedents were identified: privacy risk, privacy control and management, knowledge and information, individual differences, and privacy policy characteristics. This study highlights the need for greater attention to be paid to the methodological design and theoretical underpinning of future research. Quantitative studies should carefully consider the use of CB-SEM or PLS-SEM, should aim to increase the sample size, and should improve on analytical rigor. In addition, to ensure that the field matures, future studies should be underpinned by established theoretical frameworks. This review reveals a notable absence of privacy fatigue research when modeling the influence of privacy threats and invasions and their relationship with privacy burnout, privacy resignation, and increased self-disclosure. In addition, this review provides insight into theoretical and practical research recommendations that future privacy fatigue researchers should consider going forward.

1. Introduction

Internet users make multiple privacy-related decisions every day, some of which are suboptimal, leading to their privacy being violated [1,2]. This occurs even though they seemingly do care about their privacy. This apparent contradiction has led to the coining of the term privacy paradox [3]. However, Solove (2021) [4] declares this paradox to be a myth, arguing that the paradox is an artefact of the way concerns and behaviors are measured and observed in different contexts. This leads to the appearance of a paradox but does not constitute evidence of its existence. Whether the paradox exists or not, it is undisputed that individuals do not always act to preserve their privacy. Choi et al. [5] have suggested that one explanation for this apparent paucity of privacy-protective behaviors by internet users is privacy fatigue. Privacy fatigue occurs where the user of an app, social media platform, website, or online environment experiences exhaustion and cynicism in relation to preserving their privacy over an extended period [5].

Some researchers suggest that this might be related to feelings of helplessness triggered by unrelenting news of data breaches in the media [6]. Others argue that it stems from a negative attitude towards privacy-protective behavior [7] and a general defeatist approach to online privacy [8]. Whatever its source, suffering from excessive levels of privacy fatigue has the potential to undermine an individual’s online privacy, making it a worthwhile phenomenon to examine. This is not to mention the central role privacy plays in the IS discipline and related artefacts [9]. However, little research has been conducted with a specific focus on privacy fatigue. Often, those who do study privacy fatigue conceptualize it differently by referring to it as exhaustion, cynicism, helplessness, or powerlessness. This makes it difficult to synthesize the associated results given the lack of consensus on how it is conceptualized. Additionally, there is a lack of studies that systematically summarize existing online privacy fatigue research with the aim of pointing out promising areas for future research. It would, therefore, be valuable to investigate how online privacy fatigue has been studied thus far and in doing so map the current research landscape. This would not only allow for a summary of the important topical aspects often studied in relation to privacy fatigue (i.e., the antecedents used, conceptualizations thereof, and outcomes identified) but also for an overview of the chosen methodological approaches.

The objective of this scoping review is therefore to provide researchers with an overview of the current research landscape pertaining to online privacy fatigue with the aim of establishing an informed research agenda. To assist in the development of the research agenda, the following research questions were posed:

- RQ1.

- What methodological approaches are typically used when studying online privacy fatigue? The aim of this question was to understand what different methods (both qualitative and quantitative) have been used when studying online privacy fatigue. Additionally, it aimed to critique the application of the methods used to guide the development of recommendations that formed part of the research agenda.

- RQ2.

- How is online privacy fatigue conceptualized in extant literature? Researchers do not always explicitly conceptualize and explain their understanding of privacy fatigue. This question aimed to extract and summarize how the extant literature has conceptualized online privacy fatigue to provide some consensus in this regard. Answering this question could assist in the design of a suitable methodology (e.g., choosing appropriate measurement items).

- RQ3.

- What are the antecedents of online privacy fatigue and how does extant research relate them to the outcomes thereof? This question aimed to provide a conceptual link between the antecedents and outcomes identified to indicate where most antecedent-based research is currently clustered. Together with RQ2, this information could be used to conceptualize online privacy fatigue using novel combinations of antecedents to explore under-researched outcomes.

By addressing these questions, this scoping review contributes on several fronts. First, it provides a summative overview of the theories and methods used. Second, it provides a holistic view of the way the extant research has conceptualized privacy fatigue. Third, it produces a clear understanding of the conceptual link between the antecedents used and the outcomes of online privacy fatigue. Fourth, and most importantly, it establishes a research agenda consisting of several research recommendations—all of which aim to guide future online privacy fatigue research. This scoping review is structured as follows: Section 2 lays out the method, with the Appendix A reporting on the results of the data charting process. Section 3 reports on the findings, and Section 4 discusses these by making several research recommendations. Section 5 discusses the limitations of this study, and Section 6 draws conclusions.

2. Method

This study followed the scoping review approach of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [10]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used to inform the protocol for this review.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Articles were included if they (1) sampled a population that comprised any form of online user (including the Internet, social media, web apps, and websites); (2) dealt with the concept of privacy fatigue within an online context; (3) were published from 2004 onwards to coincide with the rise of Web 2.0 [11]; and (4) used empirical data. Articles were excluded if they (1) comprised conceptual studies (i.e., studies containing no empirical evidence); (2) were systematic reviews or meta-analyses; (3) focused on privacy fatigue outside of a technological context; and (4) were not written in English.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search took place in June 2022 using six academic databases that covered a wide range of disciplines (both behavioral and technological): ScienceDirect, Emerald Insight, Scopus, ACM, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley. In addition, a backward search was undertaken using the reference list of each of the included articles, while a gray literature search was undertaken using Google Search. The search process used the search strings outlined in Table 1 to maximize the number of relevant studies found. Search terms were derived from keywords listed in relevant articles with the aid of the population, content, and concept (PCC) framework. To enhance the rigor of the search strategy, search terms that explicitly referred to “outcomes” and “antecedents” were not included to gather as many results as possible before the screening. The search results were exported in the RIS format.

Table 1.

Search strings (and keywords) used to identify relevant sources.

2.3. Study Selection

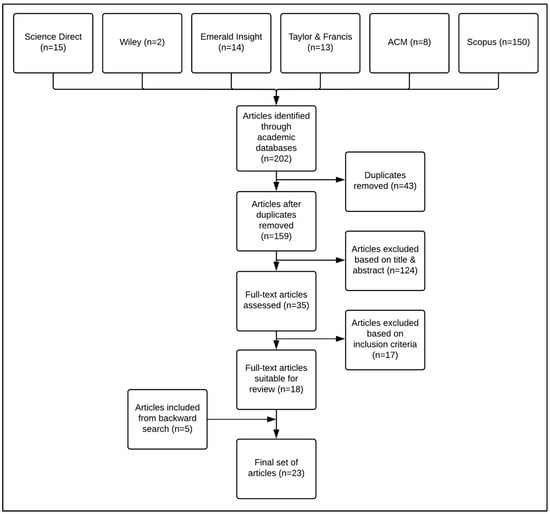

The articles were screened in Mendeley, which was also used to remove duplicates. The first screening stage was applied to the titles and abstracts, followed by the second screening stage, which was applied to the full texts. Full texts were included if they contained information relevant to the review questions and fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 provides a summary of the study selection process in the form of a PRISMA-ScR diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.4. Data Charting and Analysis

The data charting table (see Appendix A) contains essential information derived from the 23 articles used for this scoping review. The following information was extracted from each article: reference, study design, country, analysis method, online privacy context, the conceptualization of privacy fatigue, theoretical framework, antecedents, outcomes, findings, and research implications. No appraisal of the quality of the articles was conducted.

3. Findings

The study selection process yielded 23 articles reporting on research conducted in eight countries. Of these, seven studies were conducted in the United States, five in China, four in Germany, two in South Korea, and one in each of the following countries: Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, and the United Kingdom. It is worth noting that there was a clear absence of privacy fatigue research within African and Australasian countries.

3.1. Methodological Approaches Used to Study Online Privacy Fatigue

Most of the articles reviewed contained a quantitative component in the overall study design (n = 17). Of these articles, most used a purely quantitative design (n = 14) or combined this with a qualitative design (n = 3) (i.e., a mixed method design). The remainder of the articles were purely qualitative (n = 6).

3.1.1. Theoretical Frameworks and Study Designs

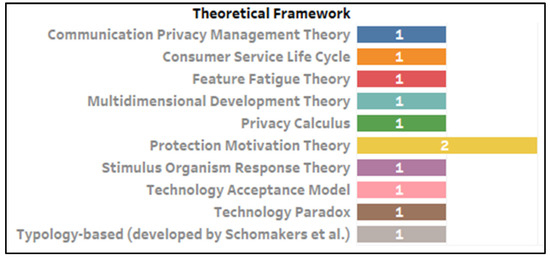

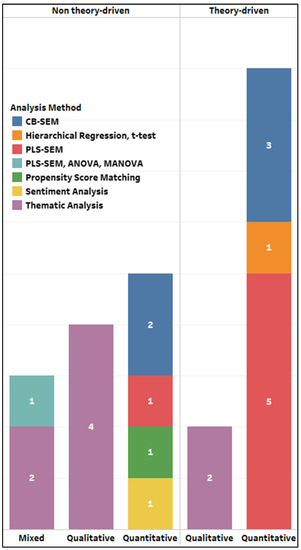

Despite the large number of quantitative articles, fewer than half (n = 11) were theory driven (i.e., used or adapted an existing theoretical framework). Interestingly, even among those articles that did use a theory, only two articles used the same theoretical framework, as illustrated in Figure 2. Most of the theory-driven articles (n = 9) made use of a quantitative study design with only two theory-driven articles making use of a qualitative design (Figure 3). Of those articles that were not theory driven (n = 12), five made use of a quantitative design and four made use of a qualitative design. Only three of our review articles made use of a mixed methods design (i.e., quantitative and qualitative).

Figure 2.

Theoretical frameworks used.

Figure 3.

Visual summary of the study designs by analysis method.

3.1.2. Analysis Methods Used

Figure 3 highlights that most of the quantitative articles made use of structural equation modeling (n = 11), that is, either partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) or covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM). Only one quantitative article made use of hierarchical regression. All the qualitative articles used thematic analysis, making it the second most used method of analysis when studying privacy fatigue as defined in this context (n = 8).

3.1.3. Empirical Situations Encountered

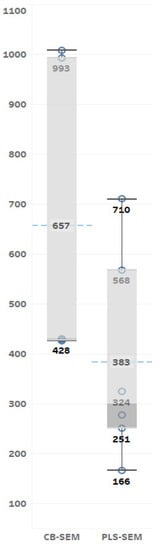

A sizable number of articles sourced empirical data from a social media platform (n = 7). Of these, two focused on Weibo and another two on WeChat. Surprisingly, only one qualitative article focused on Facebook (now called Meta), with the others focusing on social media in general (i.e., not one specific platform). Further analysis revealed that quite a few articles (n = 7) took their samples from university student populations. Only two of these articles were purely quantitative in nature, indicating that most university-based privacy fatigue research is qualitative in nature. A further seven articles sampled the internet population at large. Several articles (n = 5) made use of survey panels (such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk) to assist in participant recruitment. The CB-SEM articles used larger samples with a mean sample size (M = 657) that was significantly larger than that of the PLS-SEM articles (M = 383) (Figure 4). There was no evidence to suggest that any of the quantitative articles performed a power analysis of the samples used—either a priori or post hoc.

Figure 4.

Sample size analysis by SEM technique.

3.2. The Conceptualization of Online Privacy Fatigue

Conceptualizing online privacy fatigue is an important aspect to consider when designing a quantitative study, particularly when deciding on the measures that will form part of a study questionnaire. Best practice dictates that such measures are explicitly motivated and aligned with the conceptualizations of the variables or constructs to be measured [12].

3.2.1. A Cynical Means of Coping

The articles reviewed conceptualized privacy fatigue as a state of mental and psychological exhaustion that requires a cynical means of coping. The analysis also revealed additional (and more specific) conceptual details as to why users often need to cope with privacy fatigue. These are detailed below.

Loss of Control

Most of the articles reviewed (n = 17) conceptualized privacy fatigue by linking the resultant fatigue and exhaustion to a loss of control, specifically in relation to users’ personal information, which is disclosed (or seized) in a variety of technological and behavioral contexts. These contexts included modeling the influence of personality traits [13], uncontrollable interactions with chatbots [14], interactions on the Internet [15,16,17], unclear (or nontransparent) privacy information/agreements [18], and the use of smart voice assistants [7]. In quite a few instances (n = 5), the loss of control is linked to the use of social media [8,13,19,20,21]. Two articles conceptualized online privacy fatigue as a form of exhaustion in response to a loss of control within the context of app use, either general apps [22] or mHealth apps [23]. The remaining articles within this subtheme conceptualized privacy fatigue as exhaustion caused by the loss of control of personal information stored and transmitted via smart devices [24], online vendors [5], and the Internet in general [25].

The Futility of Privacy Protective Behavior

The remaining articles (n = 6) indicated that privacy fatigue is also conceptualized as a feeling of exhaustion brought on by powerlessness. As such, users resign themselves to the fact that it is only a matter of time before they fall victim to a privacy breach—something that is not within their power to prevent [26,27,28]. Such views of eventual victimization, as a function of privacy invasions and breaches, further fuel beliefs that the adoption of privacy-protective behavior is futile [29]. This perpetuates the belief that privacy awareness or knowledge is something best left to researchers and academics. Furthermore, one article [6] attributes such views to privacy generalizations whereby users justify their views by using highly publicized privacy breaches to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of adopting protective behavior [30].

3.3. The Antecedents and Outcomes of Online Privacy Fatigue

Privacy fatigue antecedents and outcomes were identified in 21 articles. One article provided no clear indication as to what antecedents were modeled, while another provided no outcome. It became clear from the initial analysis that there are several related subcomponents that define the larger concept of privacy fatigue, which necessitated some flexibility when identifying the antecedents. Additionally, some of the quantitative articles explicitly modeled privacy fatigue as a dependent or endogenous variable. In contrast, others modeled privacy fatigue (or the subcomponents thereof) as a moderating variable. Unlike some reviews, and to increase the depth of this analysis, antecedents were identified from the interpretive analysis of the purely qualitative (and mixed) articles selected. After identifying the antecedents and outcomes, they were categorized and then used as a means to structure the findings summarized below.

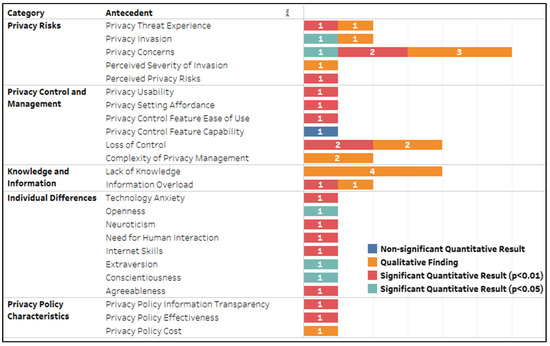

3.3.1. Antecedents of Privacy Fatigue

From the analysis, five categories of privacy fatigue antecedents emerged (Figure 5). The focus was not on finding as much theoretical overlap as possible (to assist in merging them, for example) but rather to illustrate them accurately as used in the source articles. To effectively guide future research, the level of significance was also taken into consideration. From a significance point of view, most of the antecedents would likely add value to future research, as most achieved a statistically acceptable level of significance as used. Only one antecedent was found to be nonsignificant, with the majority of the quantitative results (n = 16) attaining a high degree of significance (p < 0.01). Most of the more prominent antecedents (those with higher frequencies) were identified from qualitative articles (noted as a significant qualitative finding in the legend). This is an interesting finding given that most of the articles used a quantitative study design.

Figure 5.

Privacy fatigue antecedents by level of significance.

The Influence of Privacy Risks

Over half of the articles (n = 12) investigated the influence of at least one antecedent related to privacy risk (Figure 5). These antecedents measured the influence of participants’ experience with privacy invasions or threats (i.e., privacy threat experience) and the concerns that surround them. Privacy concerns in particular were identified as a prominent antecedent in both the qualitative and quantitative articles reviewed. At least one of the articles [29] found privacy concerns to significantly influence fatigue—a finding most applicable to those who are skilled internet users. Rajaobelina et al. [14] proved the link between creepiness and privacy concerns. In their study, users expressed shock and resignation (followed by fatigue) at the extent to which an insurance chatbot was able to use limited personal information to tailor very detailed insurance profiles. Here, too, users felt it futile to engage in protective behavior despite significant privacy concerns.

Similar findings were reported by Schomakers et al. [26], who found significant links between digital resignation and privacy cynics. Similar to Lutz et al. [29], Schomakers et al. [26] also found skills (self-efficacy in their context) to moderate the influence of privacy concerns. On the other hand, one of the qualitative articles [16] found concerns to be weakened by privacy cynicism similar to the findings of Choi et al. [5], who report privacy concerns to statistically interact with fatigue when dealing with online vendors. According to Hargittai and Marwick [15], such privacy concerns are only significant in a social setting as opposed to an institutional setting, in other words, where the privacy of a user’s personal information is subject to the privacy behavior of those in their social sphere as opposed to information harvested by companies. In addition to privacy concerns, three articles investigated antecedents associated with privacy invasions. Two of these articles explicitly investigated the influence of privacy invasion or threats as conceptualized by Hoffmann et al. [16].

Similar to Hoffmann, Lutz et al. [14] found evidence to suggest that, despite having experienced privacy invasions, a significant portion of users still avoid privacy-protective behaviors, this despite also being made aware of the PRISM surveillance program and Cambridge Analytica [6]. Similar findings are reported by Hinds et al. [19], who found that privacy invasions are inevitable, with most Facebook users living in privacy invasion denial. Again, privacy invasions are not viewed as a possibility but rather as an eventuality. One article found these views to extend even to the use of IoT devices, where users perceive their personal information to be particularly vulnerable [24]. Oh et al. [24] also happen to be the authors that quantified the influence of perceived severity of invasion. Their findings indicate that participants viewed IoT privacy invasions (such as viewing unauthorized CCTV footage) to be significantly more severe than those that take place in other IT environments (e.g., social media). Contrary to the influence of perceived severity of invasion, Shao et el. [13] found information overload to have a more significant effect on privacy fatigue than perceived privacy risks when using Weibo.

The Role of Privacy Controls and Privacy Management

Several articles (n = 9) investigated the influence of privacy controls or the management thereof (see Figure 5). The loss of control featured most (n = 4), especially in the results of qualitative articles. For example, Hinds et al. [19] found that a significant number of students perceived the loss of Facebook privacy controls to be irrelevant, as the level of privacy controls had no direct bearing on successfully protecting one’s personal information. The loss of control simply furthers the associated feelings of privacy denial, fatigue, and ultimately digital resignation (i.e., privacy invasions being inevitable). Hoffmann et al. [25] and Stanton et al. [31] reported similar findings, adding that a loss of privacy controls within the context of general internet use also influences feelings of uncertainty, powerlessness, and mistrust, all of which contribute to privacy fatigue. One article [8] reported that teens are particularly fatalistic in terms of such privacy invasions (referred to as network defeatism), opting to manage and control social media privacy on an interpersonal rather than a personal level. Six articles explored the difficulty of managing privacy controls (also referred to as settings). Two of these reported that overly complex privacy controls (i.e., complexity of privacy management) significantly increase overall fatigue [15,19]. Interestingly, younger users did not view such complexities to be as significant when considering institutional privacy concerns, which mirrors the results of Hargittai and Marwick’s earlier research [15]. Rajaobelina et al. [14] found evidence to suggest that a reduction in complexity (by increasing privacy usability) significantly reduces fatigue, with Zhu et al. [23] reporting similar results when increasing privacy setting affordances in an m-health mobile app (i.e., the range and extent of privacy controls provided). Finally, one article reported that although an increase in the ease of privacy control (modeled as privacy control feature ease of use) significantly reduced fatigue, the same did not apply to the relationship between privacy control feature capability and privacy fatigue when using a mobile app [22]. Together, the above suggests that, within the context of a mobile app, a reduction in complexity significantly reduces privacy fatigue.

Knowledge and Information

Four articles reported that a lack of knowledge significantly influenced privacy fatigue making it the second most common antecedent identified. Knowledge seemed to play a significant role when interfacing with technologies such as smart or IoT devices, specifically when recording audio. For example, Dunbar et al. [30] found a lack of privacy notifications and warnings about possible infringements to be particularly problematic within the context of recording-capable smart devices. Similarly, Oh et al. [24] found participants’ lack of knowledge to increase feelings of privacy fatigue when using smart healthcare devices at home. A lack of knowledge was also found to significantly increase fatigue within the context of internet-based self-disclosure and participation [16,25]. One article modeled the influence of information overload, reporting that, within the context of Weibo interactions, its effect on privacy fatigue was significantly larger than that of perceived privacy risks [13]. Similar results were reported by Stanton et al. [31] who found that too much information overwhelms users, making them weary and desensitized to security and privacy risks.

The Influence of Individual Differences

Three articles were identified which modeled a variety of antecedents that could be classified as individual differences (see the fourth category in Figure 5). Of these, the article by Rajaobelina et al. [14] investigated technology anxiety and the need for human interaction, reporting that both of these significantly influenced privacy fatigue when using an insurance chatbot. One article focused on the influence of personality traits, with neuroticism being found to be the most influential despite the other four traits (extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness) also exhibiting significant influences on privacy fatigue [20].

Privacy Policy Characteristics

Despite the integral role of privacy policies online, only three articles were found that modeled its influence. Although these antecedents were found to significantly influence privacy fatigue, some of the findings are somewhat surprising. For example, Agozie and Kaya [18] found that the more transparent e-government websites are (modeled as privacy policy information transparency) in terms of privacy issues, the larger the positive effect is on emotional exhaustion, which forms a core subcomponent of privacy fatigue [5]. Privacy policy effectiveness was also found to significantly influence privacy fatigue within the context of mHealth app self-disclosure [23]. More specifically, an increase in perceived effectiveness was found to reduce privacy fatigue. Conversely, the cost of engaging with IoT privacy policies (modeled as privacy policy cost) was found to increase privacy fatigue [24].

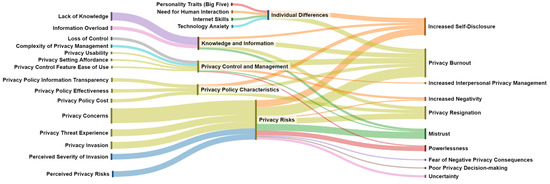

3.3.2. Outcomes of Online Privacy Fatigue

Several outcomes of privacy fatigue were identified. These outcomes were mapped to the antecedent categories by way of a Sankey diagram (Figure 6). It is worth noting that categories are mapped in a proportional manner. This is an important distinction, as the findings of some articles led to the identification of multiple outcomes aligned to only a few antecedents. This is indicated by the thickness of the flows as is the case for privacy risk antecedents which are associated with numerous outcomes—more so than any other category of antecedents. A brief summary of the outcomes related to privacy fatigue is presented below.

Figure 6.

Sankey diagram of online privacy fatigue antecedents (far left) and outcomes (far right).

Privacy Burnout

Over half of the articles found privacy fatigue to lead to a general disinterest in engaging with privacy-protective behavior (Figure 6). This includes the use of privacy controls and settings, as well as taking heed when it comes to reading and complying with privacy policies. Privacy concerns are particularly influential when it comes to privacy burnout [5,16,26]. The more concerns users have, the more disengaged and “burnt out” they become—an outcome that is amplified by the other antecedent categories. For example, knowledge and management [30], as well as privacy controls [22] and management, contribute to privacy burnout in near equal proportions, mostly owing to a lack of information, loss of control [13,24], or complex privacy management [17,19]. Interestingly, experiences with privacy invasions and threats played a lesser role, with only threat experience contributing a small amount to privacy burnout. This is, however, not an uncommon finding within the context of recent threat-based research, with most users being largely impervious to threat appeals [32,33].

Increased Self-Disclosure and Poor Privacy Decision Making

From the mapping table analysis it is clear that an increase in self-disclosure goes hand in hand with privacy burnout. This is particularly relevant when such self-disclosure takes place as a function of individual differences and privacy concerns. As such, increased levels of privacy fatigue are a function of individual differences and increased concerns, and privacy policy transparency increases self-disclosure [5,13,15,16,18,20,21,28].

Privacy Resignation

This analysis revealed slight—albeit important—differences between privacy resignation and privacy burnout. Unlike privacy burnout, the review articles linked privacy resignation more closely to privacy threat experience and not at all to privacy control and management [17,24,25,29]. This is an interesting finding, indicating that extant research has not explored the link among privacy controls, settings, and privacy resignation as an outcome of privacy fatigue.

Mistrust and Powerlessness

Although mistrust and powerlessness as outcomes are illustrated separately, they are discussed together, given their interesting relationship with privacy invasions. For example, the review indicates that powerlessness is only a likely outcome of privacy fatigue when studying user perceptions of privacy invasions [24,29]. However, when privacy invasions are studied as an actual event (i.e., having suffered a privacy invasion), the resultant fatigue leads to a sense of mistrust [16]. An interesting finding of this review is that it reveals no link between privacy threat experience and mistrust. Similarly, this analysis also revealed no link between mistrust and powerlessness (as outcomes of fatigue), even though the articles reviewed focused on the influence of individual differences or privacy policy characteristics.

Fear, Uncertainty, and Increased Negativity

This analysis also revealed that privacy fatigue can, in some instances, result in increased fear, negativity, and uncertainty. Having said this, this analysis only found this to be the case when the articles investigated the influence of perceived privacy risks and, to some extent, privacy controls and management. None of the articles analyzed made a link between knowledge and information, privacy policy characteristics, or individual differences and the outcomes of fear, uncertainty, and increased negativity. Surprisingly, no evidence was found to suggest a relationship between privacy invasions, threats, or concerns.

Increased Interpersonal Privacy Management

A positive outcome was identified that relates directly to privacy usability. Despite its relatively small contribution to the Sankey diagram, the absence of a relationship with knowledge and information was of particular interest, especially if one considers that a lack of information would adversely affect privacy management, as users are unfamiliar with the privacy controls and settings. In a similar way to privacy burnout, none of the privacy risk antecedents influence privacy fatigue to the extent that users start increasing privacy management. Therefore, according to this analysis, no amount of privacy threat experience, invasions, or concerns are visceral enough to lead to an increase in privacy management. Instead, users simply disengage and increase self-disclosure when they experience heightened levels of privacy fatigue.

4. Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to provide researchers with an overview of the current research landscape pertaining to online privacy fatigue with the aim of establishing an informed research agenda. Of particular interest was understanding how extant research has conceptualized privacy fatigue, the methodological approaches that have been used, as well as the antecedents modeled, and outcomes identified. In this section, we provide a recommendation-driven discussion of our research agenda. First, we discuss the methodological and theoretical aspects that researchers should consider going forward. Second, we discuss promising areas for future research given the findings illustrated in Figure 6. To our knowledge, this is the first study to put forward an online privacy fatigue research agenda.

4.1. Methodology and Theory

Recommendation 1: Researchers should explicitly conceptualize the phenomenon of interest within the context of their chosen theoretical framework. This should be carried out for each latent variable, regardless of the study design. Quantitative research designs should be accompanied by a well-specified questionnaire that clearly conceptualizes each latent variable within the context of the chosen theoretical framework. It should also align the measurement items in the questionnaire (i.e., the questions) with the latent variables. Qualitative research designs should conceptualize the similarity of their model variables by aligning the interview guide questions with the variables within the chosen theoretical framework. Although it was possible to obtain a clear understanding of how the reviewed articles conceptualized online privacy fatigue, many of the latent variable measures in these articles were not conceptualized in enough detail.

Recommendation 2: Researchers should carefully consider how (and where) they collect their primary data. This applies to both quantitative and qualitative research and should not be solely determined by that which is deemed cost effective and convenient. For example, several of the review articles gathered primary data from university students. Although student populations are suitable for studies focused on student-specific privacy research, most of the articles reviewed were not thus focused. Researchers should, therefore, obtain representative samples that enable the generalizability of results [34,35]. It was refreshing to see quite a few articles (n = 5) that used crowdsourced survey platforms (such as Amazon Mechanical Turk) to enhance the demographic diversity of their samples. These platforms also enable researchers to set very specific sampling criteria while ensuring overall cost-effectiveness [36]. Some of these platforms (e.g., Prolific) could even be used to gather representative samples, which some claim surpass those that can be obtained via MTurk [37]. As such, researchers are encouraged to carefully consider their study designs before selecting a survey platform. This applies specifically to studies focused on the behavioral influence of individual differences, where MTurk participants (also called workers) have been found to be more introverted, have lower levels of self-esteem, and higher cognitive needs [38], all of which may introduce sampling bias. Additionally, several articles gathered primary data from social media platforms, of which most were Chinese based. Some of the more popular social media platforms were either not used or not explicitly specified. For example, only one article collected data exclusively from Facebook, with a clear absence of Instagram-focused studies. It must be conceded that several articles focused on social media in general, but such approaches make comparisons difficult and complicate platform-specific theorization, something that would benefit this field of study.

Recommendation 3: Researchers should make use of (or adapt) established theoretical frameworks best suited to the study of online privacy. This is an important consideration given our view that the study of online privacy fatigue is immature. Several articles made use of CB-SEM, which is confirmatory in nature. However, even these articles failed to use an established theoretical framework. Failure to move from exploratory to confirmatory methods implies that privacy fatigue research will remain immature, unable to empirically substantiate theoretical matters such as what is sufficient in terms of statistical accuracy. Future research could, for example, use protection motivation theory, which is well suited to some privacy fatigue research because of its focus on the role of threats and risks [39,40,41], especially when considering that threats and risks featured prominently in this review (Figure 6). Additionally, of all the articles reviewed, only two used a privacy-centric theoretical framework (see Figure 2), and despite privacy concerns also featuring prominently as an antecedent, none of the reviewed articles used (or adapted) established privacy frameworks focused on modeling privacy concerns. This is problematic as it does not advance the study of privacy fatigue (as influenced by privacy concerns) within the context of established (and more suitable) theories, such as concern for information privacy (CFIP), internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC), and antecedents–privacy concerns–outcomes (APCO) [42]. The use of APCO is particularly appealing, as it has shown promise in recent privacy research [43,44] and has also been used to model the influence of individual differences in a privacy context [45,46]. For health-related studies, the use of the health information privacy concern (HIPC) scale is recommended, but researchers are cautioned to model it multidimensionally, as this is the norm [47,48]. Such theoretical aspects were notably absent from review articles focused on mHealth or smart healthcare. The use of theoretical frameworks also applies to qualitative privacy fatigue research. Avoiding the use of theory limits formal theorizing and, in fact, only one qualitative article used a framework. Such forms of theoretical imbalance may yield weaknesses. Conversely, the use of a well-defined (and established) theoretical framework enhances qualitative findings [49].

Recommendation 4: Quantitative researchers should make an informed decision when selecting either CB-SEM or PLS-SEM. If, for example, the objective of a study is to achieve path estimate consistency, then a CB-SEM approach is preferable [50]. The same applies to confirmatory studies where theory testing takes place [50,51]. This is important given the sparse use of theoretical frameworks in the articles reviewed. The use of CB-SEM is also recommended when the measurement philosophy is based on common variance [52]. It is worth noting that this aspect was not explicitly specified in any of the articles reviewed. Despite this, there may be instances where it is acceptable (and even preferable) to use PLS-SEM, one such example being the estimation of formative (as opposed to reflective) models [53]. Although the theoretical differences between these two types of model are beyond the scope of this review, privacy fatigue researchers may wish to read Freeze and Raschke [54] or Hair, Matthews et al. [55] and explicitly specify these aspects in the future. This analysis also revealed that the reviewed articles that used SEM failed to classify their models as either common factor or composite in nature. Such classification is a contentious matter, and although Evermann and Rönkkö [50] argue that PLS-SEM is unable to estimate common factor models (as CB-SEM is preferred for this), many researchers do so because they either avoid classification or are unaware of its significance. To address such classification problems, researchers should use a consistent form of the PLS algorithm (e.g., the PLSc option in SmartPLS), especially since PLSc can accommodate both common factor and composite models [56,57]. In doing so, a failure to classify models would not adversely affect the results to the same extent as being ignorant in this regard.

Recommendation 5: Quantitative researchers should use larger samples and not use said sample sizes to determine which SEM technique to select. If a smaller sample is desired, some form of sample size power analysis must be carried out. There is evidence to suggest that this advice was not adhered to in the articles reviewed, especially given the smaller sample sizes of the PLS-SEM articles reviewed (Figure 3). In fact, the use of PLS-SEM is plagued by several misconceptions when it comes to sampling and overall study design [12]. In short, PLS-SEM is not superior when it comes to estimating models based on small sample sizes [12]. Although PLS-SEM will estimate models using small samples, such estimates are most likely inaccurate [50,51,58]. The absence of sample size power analyses is also problematic, as these are required to ascertain what is deemed sufficient in terms of statistical accuracy. This is a vital step as it enables researchers to select a sample size that will enable them to determine the significance of effects of certain magnitudes [12]. Larger sample sizes are more suited to detecting significant small effects, which is desirable in almost all instances.

Recommendation 6: Qualitative researchers should demonstrate the analytic rigor that accompanies their analyses and resultant findings. This review indicated a lack of analytic rigor in the way the findings in the qualitative articles were reported (and possibly analyzed). For example, very few (if any) provided much detail on how their thematic analyses were carried out. Details such as codes (and codebooks) and thematic maps, as well as how these were refined, were not provided in most articles. Given the prolific use of quotes and detailed findings in some articles, it is suspected that these analytic steps were indeed carried out but not reported in detail. Even doing so as part of an Appendix A would greatly improve said rigor, as well as the validity of the findings. For thematic analyses, the seminal work of Braun and Clarke [59] is recommended, which provides detailed guidance in this regard. Its application in recent privacy research is encouraging [60,61,62,63,64].

Recommendation 7: Researchers should consider making use of mixed methods study designs. When combined with a thorough literature review, such designs not only benefit from the advantages offered by quantitative and qualitative research, but also ensure the triangulation of results [65,66]. Only three articles used a mixed methods design, making this design a clear candidate for improving privacy fatigue research going forward.

4.2. Future Research

Recommendation 8: More research should be conducted on the influence of privacy control and management. Studying these antecedents is particularly important given that they shape privacy expectations [42]. Additionally, and given their strong links to human–computer interaction (HCI) research, these studies are practical and likely candidates for mixed study designs because the focus is on obtaining user feedback on what should be considered when trying to improve their privacy online. This could take the form of studies focused on investigating the effectiveness of various notification mechanisms, such as just-in-time notifications, layered notifications, and icons. Very little research is available on the effectiveness of such notifications within the context of online privacy fatigue. This review also indicates that there is very little research on the influence of privacy management and control mechanisms on privacy resignation. Given its prominence as a privacy fatigue outcome and the rise in recent research focused on privacy resignation [67,68], it would make sense to explicitly combine such research with antecedents known to influence privacy fatigue.

Recommendation 9: Researchers should model the influence of personality traits (and other individual differences) to a greater extent when conducting privacy fatigue research. In this review, only one article modeled the influence of personality traits, despite the plethora of recent privacy-related research that focuses on personality traits [69,70,71,72,73]. Similar to Tang et al. [20], theorizing the influence of personality traits is recommended, but it is suggested that these traits be modeled as a series of interaction terms with one (or all) of the following antecedents: privacy concerns, privacy threat experience, and privacy invasion experience. As conducted by van der Schyff et al. [71], modeling antecedents in this manner enables researchers to uncover which interaction terms significantly influence privacy fatigue (and to what extent). Even more detailed results could be obtained if the above interaction terms were modeled for different participant groups as part of a multigroup analysis. Such multigroup analyses were completely missing from the articles reviewed. Together, the above study design would enable researchers to make specific conclusions on the influence on privacy fatigue. For example, it may be concluded that privacy fatigue is high in male Facebook users who display high levels of neuroticism. Detailed findings such as these could be used to improve social media privacy mechanisms. If conducted within the context of a mixed study design such quantitative results could be supplemented with (and confirmed by) interviews or focus groups—not to mention apps that monitor a user’s interactions with a social media platform. A study design as outlined above would provide a novel contribution, especially if conducted on multiple popular social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and even LinkedIn). Such comparative research was missing from the articles reviewed. Additionally, none of the articles reviewed investigated the influence of individual differences and mistrust, as well as powerlessness—both of which emerged as sizable outcomes of online privacy fatigue (see Figure 6).

Recommendation 10: Researchers should model the influence of privacy policy characteristics with a specific focus on how these characteristics influence trust and powerlessness within the context of online privacy fatigue. For example, none of the articles reviewed that studied privacy policy characteristics (such as privacy policy transparency, privacy policy effectiveness, and privacy policy cost) modeled its influence on trust (or mistrust) and powerlessness, despite mistrust and powerlessness being identified as prominent outcomes of online privacy fatigue.

Recommendation 11: More privacy fatigue research should be conducted on the influence of knowledge and information. Specifically, such research should focus on the extent to which information overload influences a user’s level of powerlessness (or possibly learned helplessness) within the context of online privacy fatigue. Research on this is absent from the literature, and those that do study related aspects within a privacy context (such as learned helplessness) have done so by focusing on privacy concerns and perceived stress [74] instead of fatigue.

Recommendation 12: In addition to the above, more research is required on the relationship between online privacy fatigue and differential privacy as a form of privacy-preserving technology. This is especially important within the context of information misuse given that such technologies enable user data to be analyzed while preserving the privacy thereof [75,76]. Users may still feel fatigued (and daunted) by these technologies, despite the sheer number of options and settings accessible to them when using privacy-preserving technologies [77]. For instance, Apple’s differential privacy feature enables customers to choose whether or not to share specific data with the company, but this option is tucked away in the settings menu and may not be readily visible to users. In addition, some users might not completely comprehend the ramifications of choosing to utilize or forego particular privacy-preserving technologies, which could make them frustrated or uninterested in controlling their privacy settings [78]. Thus, while privacy-preserving methods are crucial for safeguarding user information, it is also necessary to take into account how these methods may increase online privacy fatigue. To avoid privacy fatigue, developers and businesses should work to build clear, understandable privacy settings and policies that are simple for consumers to maintain.

Recommendation 13: We also advise future researchers to further explore online privacy fatigue as a coping mechanism, particularly when apps and systems are used in an ephemeral way. We argue that privacy fatigue, as a means of coping with complex and overwhelming privacy technologies, may be related to ephemerality [79]. For example, employing platforms that offer temporary or self-deleting content (i.e., ephemeral content) may provide comfort to people who feel overwhelmed by the constant need to control their online privacy using complex settings and technologies. This might lessen the necessity for continuing privacy management. Having said this, we caution researchers to be cognizant that ephemera-based features may also cause privacy fatigue if people feel as if they are losing control over their personal information or find it difficult to keep track of what data are shared or removed. Therefore, the nature and scope of the relationship between these two concepts would require more investigation.

5. Limitations

Although a rigorous study selection and analysis process was followed, this scoping review is not without its limitations. First, the articles selected are limited by the chosen academic databases, which are, in turn, limited by the publication subscriptions purchased by the authors’ institutions. Second, the data charting process (and resultant categorizations) is interpretive and, therefore, subject to some variation if analyzed by other researchers. Third, only articles that satisfied our inclusion criteria were included (which included only focusing on empirical articles). Editorials, related scoping reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded. For example, Barth et al. [80] carried out a systematic review of privacy but did not focus primarily on privacy fatigue. Kern et al. [81] reviewed the literature on experimental privacy studies, with a focus on self-disclosure, and not privacy fatigue. Neal et al. [82] consider the features of privacy policies that might trigger privacy fatigue, but do not explore the phenomenon itself. We were also unable to find any relevant gray literature via Google Search. Despite these limitations, this review presents an accurate summary of published empirical work in the field of online privacy fatigue.

6. Conclusions

The objective of this scoping review was to establish a research agenda to guide future online privacy fatigue research, in particular by highlighting which methodological approaches have been used, how privacy fatigue has been conceptualized, and the antecedents that have been modeled thus far. The review also identified the outcomes of online privacy fatigue. This analysis indicated that most of the research on online privacy fatigue has been quantitative in nature, making extensive use of structural equation modeling (either CB-SEM or PLS-SEM). This analysis also indicates that online privacy fatigue is often conceptualized as a concept that measures participants’ views on the futility of privacy-protective behavior. Similar evidence was found during this analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of online privacy fatigue, with the majority of the articles indicating that online privacy fatigue leads to privacy burnout and resignation. This is a state attained when a user’s level of privacy fatigue (as a function of increased cynicism and exhaustion) reaches a point where privacy-protective behavior is ignored and self-disclosure is increased despite pertinent privacy risks. This was particularly apparent when privacy fatigue was studied within the context of privacy concern. This analysis revealed a notable absence of privacy fatigue research when modeling the influence of privacy threats and invasions and their relationship with privacy burnout, privacy resignation, and increased self-disclosure. This was especially so within the context of actual privacy threats and invasion experiences. The review concluded with a research agenda that took the form of several theoretical and practical research recommendations. These included the recommendation that the complexity of privacy control and management should be simplified, and privacy policy should be more transparent and straightforward for the user.

Author Contributions

K.v.d.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. G.F.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. K.R.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. S.F.: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Appendix A in the form of the data mapping table.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the data charting process (*** significant at p < 0.01; ** significant at p < 0.05; ns = not significant).

Table A1.

Results of the data charting process (*** significant at p < 0.01; ** significant at p < 0.05; ns = not significant).

| Reference | Study Design | Country | Analysis Method | Online Privacy Context | Conceptualization of Privacy Fatigue | Theoretical Framework | Antecedents | Outcomes | Findings | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acikgoz and Vega [7]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 277 MTurk users). | US. | PLS-SEM. | Smart device voice assistants. | Negative feelings and attitudes towards voice assistant privacy leading to privacy cynicism defined as a type of fatigue. | Technology acceptance model. | None identified. | Increased negativity, increased trust. | The more cynical users are towards privacy, the more negative their attitude towards VAs. However, unlike other studies, the more cynical, the more trust increases in VAs. | Stronger focus on the role of trust within the context of AI-based VAs. |

| Agozie and Kaya [18]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 710 university students). | Cyprus. | PLS-SEM. | E-government websites. | Emotional exhaustion and cynicism develop as a result of inadequate privacy information transparency. | Consumer service life cycle. | Privacy policy information transparency ***. | Increased disclosure of personal information. | The more transparent e-government applications are (websites in this context), the more pronounced the positive impact on emotional exhaustion and cynicism becomes. The authors argue that this reduces associated concerns and increases trust. | Consider, within an empirical setting, those noninformational aspects of transparency that influence privacy behavior within e-government. |

| Lee et al. [6]. | Quantitative (sentiment of 10,424 comments). | China. | Sentiment analysis. | Privacy sentiment on Weibo post-Cambridge Analytica. | Exhaustion and helplessness due to endless negative privacy publicity, specifically, with regard to privacy breaches. | Not used. | Privacy invasion. | Fear of privacy invasions, fear of loss of privacy, fear of inappropriate use. | The results indicate that even though the CA scandal was political, users generalize to all other areas of life. This leads to fear and a sense that the concept of online privacy does not exist. | They are incorporating the role of privacy invasion when modeling privacy-protective behavior. In other words, to what extent does suffering from an actual privacy invasion influence behavior? Additionally, the research could be performed longitudinally to quantify the influence of privacy invasion over a longer period. |

| Choi et al. [5]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 324 internet users). | South Korea. | PLS-SEM. | Personal info used by online vendors. | Avoidance of fully understanding privacy protocols, which, together with a perceived lack of control over their online privacy, leads to stress and fatigue as part of a larger state of psychological fatigue. | Not used. | Privacy concerns ** (as an interaction term with privacy fatigue). | Inability to make sound online privacy decisions, increased disclosure of personal information, privacy burnout. | The results indicate that although literature suggests a relationship between privacy concerns and fatigue, none were found here. Instead, results indicate a strong influence on intended disclosure and privacy disengagement. Fatigued individuals thus put far less effort into making sound privacy decisions. | Although hinted at during hypothesis development, future research should empirically evaluate the antecedents of privacy fatigue, specifically within the context of person-environment fit theory. |

| De Wolf [8]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 2681 teens). | Belgium. | Hierarchical multiple regression, paired sample t-tests. | Media use (and ownership) of social media users. | Networked defeatism, defined as a fatalistic attitude towards information and privacy management, in particular, because individuals are no longer able to control the privacy of their information due to technological and social violations, eventually, leading to fatigue. | Communication privacy management theory. | Loss of control *** (referred to as network defeatism). | Increased interpersonal privacy management. | The results indicate that teens who are fatalistic in terms of information privacy and control (high network defeatism) negotiate privacy boundaries on an interpersonal level instead of a personal level. | Inclusion of more specific dimensions of network defeatism, such as security, consent, and breach fatigue. |

| Dunbar et al. [30]. | Qualitative (interviews and focus groups with 35 adults). | US. | Thematic analysis. | Privacy risk inherent in the use of audio-recording-capable smart devices. | General feeling that no actions they take will improve their privacy leading to a sense of fatigue typified by resignation and disengagement, thus, accepting privacy-related defaults. | Typology-based (developed by Schomakers et al.). | Lack of knowledge. | Privacy burnout. | Simplified EULAs to support privacy decision making. Make informative use of privacy notifications and indicators. Show results and summaries of audio which may infringe on privacy (downstream effects). | Inclusion of longitudinal experiment-based elements that facilitate the collection of data in relation to actual behavior. Focus on the evaluation of designs related to downstream effects. |

| Hinds et al. [19]. | Qualitative (interviews with 30 university students). | UK. | Thematic analysis. | Facebook information disclosure. | Feeling of cynicism as a result of having resigned themselves to privacy invasions, leading to privacy, helplessness and fatigue. | Not used. | Privacy invasion, loss of control, complexity of privacy management. | Reporting privacy invasion, privacy burnout, learned helplessness. | Online privacy (as a function of targeted advertising) is viewed simplistically, with most individuals being in privacy-related denial having resigned themselves to information misuse. Having said this, some report when this occurs. | Consider researching specific features of platforms that influence privacy-protective behavior. Investigating the influence of motivation and how it may mitigate privacy fatigue. Additionally, research should investigate the role of privacy responsibilization. Specifically, between the user and the provider. |

| Hoffmann et al. [25]. | Qualitative (focus groups with 50 students), quantitative (survey with 96 internet users). | Germany. | Thematic analysis. | Internet use and related self-disclosure. | Uncertainty, powerlessness, and mistrust as they relate to the use of personal information, eventually leading to meaningless forms of privacy-protective behavior. | Not used. | Lack of knowledge. | Privacy resignation, mistrust (online service providers). | Privacy cynicism (and thus fatigue) is a function of three factors namely: uncertainty or powerlessness, resignation, and mistrust. | More effort should be made to explore mistrust and resignation in terms of statistical measures. |

| Keith et al. [22]. | Quantitative (semi-longitudinal experimentation and survey with 568 university students). | US. | PLS-SEM. | App-based self-disclosure. | The fatigue users experience when new privacy control features are introduced to an app. | Feature fatigue theory. | Capability of privacy control features (ns), ease-of-use privacy control features ***. | Privacy burnout. | Product feature capabilities play a larger role in pre-use perceptions, as opposed to feature ease of use which plays a larger role after use. If social media platforms set “open” privacy defaults and complex controls, users are likely to accept information disclosure beyond what they may find acceptable. | Further adaptations should be made to further integrate feature fatigue with privacy fatigue. |

| Lutz et al. [29]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 1008 survey panel users). | Germany. | CB-SEM. | Internet use skills and associated privacy protection. | Digital resignation as a result of an opaque (and complex) online environment where privacy protection becomes (subjectively) futile and tiring. | Not used. | Internet skills, privacy threat experience (ns for mistrust) *** rest, privacy concerns ***. | Mistrust, uncertainty, powerlessness, privacy resignation. | Internet users who experience higher levels of digital resignation are less likely to protect their privacy online. Additionally, the greater the mistrust the more protection is enacted. Powerlessness and uncertainty have no effect. | Include elements related to intensity of use, as it likely influences cynicism and fatigue. Include state forms of cynicism, fatigue, and user agency antecedents. |

| Rajaobelina et al. [14]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional experimentation and survey of 430 survey panel users). | Canada. | CB-SEM. | Users interacting with a car insurance chatbot to obtain a quote. | Creepiness experienced when technology behaves in a seemingly uncontrolled manner leading to coping mechanisms seated in digital resignation leading to fatigue. | Technology paradox. | Privacy concerns ***, privacy usability ***, technology anxiety ***, need for human interaction ***. | Negative emotions, technology mistrust, loyalty reduction. | Privacy concerns had the largest effect on creepiness. Results may vary depending on the context. Consumers should opt in when the use of personal information is at stake. | Study the influence of tendency to disclose on creepiness and broaden the setting to social media chatbots. Measure physiological reactions to creepiness and related emotions. |

| Schomakers et al. [26]. | Qualitative (interviews and focus groups with 35 users), quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 345 users). | Germany. | PLS-SEM, ANOVA, MANOVA. | Interplay between privacy concerns and protective behavior among internet users. | Powerlessness leading to fatigue concerning enacting privacy-protective behavior. | Not used. | Privacy concerns ***. | Privacy burnout, powerlessness. | The research highlights, through the identification of privacy cynics, a discrepancy between the concerns and protective behavior. Importantly this is seemingly moderated by privacy self-efficacy. Cynics lack belief in effectiveness and competence when enacting protective behavior. | Improvement and design of effective and clear guidelines for identifying the most severe privacy threats and the most effective ways to mitigate or prevent them. Concerns and protective behaviors should always be studied together. Develop privacy education programs targeting the youth. |

| Shao et al. [13]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 428 users). | China. | CB-SEM. | Users interacting with Weibo and how fatigue (as a function of traits) influences these interactions. | An individualized coping strategy moderated by personality traits. Assist coping with fatigue seated in feelings of forced acceptance, and obedience. | Stimulus organism response theory. | Information overload ***, perceived privacy risks ***. | Privacy burnout, increased willingness to self-disclose. | Information overload has a greater impact on privacy fatigue than perceived risks. Both are significant though. Personality traits significantly moderate the effect of these antecedents, notably neuroticism. | Incorporate the contextual online privacy perception model in privacy fatigue research. Future work should further incorporate information overload and conduct research on a variety of platforms. |

| Stanton et al. [31]. | Qualitative (cross-sectional interviews with 40 users). | US. | Thematic analysis. | Average users’ beliefs and perceptions about online security and privacy. | Privacy fatigue is conceptualized as a form of security fatigue that desensitizes and makes users weary about engaging in privacy-protective behavior. | Not used. | Information overload, loss of control. | Privacy burnout, privacy resignation. | Users avoid decision making and often opt for the easiest way out. When decisions are made they are often impulsive leading to feelings of powerlessness and resignation. Users also highlighted that they did not understand why they would be targeted in the first place. | More research on why users perceive their personal information to be less valuable. Given the importance of decision making, future work should focus on trying to empirically evaluate the cognitive load associated with certain privacy behaviors, possibly on a wide variety of online platforms. |

| Tang et al. [20]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 426 mobile app users). | China. | CB-SEM. | Self-disclosure via a mobile version of WeChat and QQ. | The fatigue (and associated boredom) experienced when trying to navigate complex privacy control mechanisms. | Not used. | Agreeableness ***, neuroticism ***, conscientiousness **, extraversion **, openness **. | Increased intention to disclose via the app, privacy burnout. | Privacy fatigue and concerns significantly influence intended disclosure. However, concern exerts a larger effect on intended disclosure. Neuroticism is the most influential trait. | Development of clearer and concise privacy guidelines and policies. Separate types of information based on sensitivity levels. |

| Van Ooijen et al. [27]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 993 survey panel users). | US. | CB-SEM. | Privacy decision-making process within the context of interacting online. | Cynicism as a form of powerlessness, and resignation which then lead to fatigue concerning enacting privacy-protective behavior, in turn, moderating the influences of the PMT constructs. | Protection motivation theory. | Used a moderator between the PMT constructs and privacy-protective behavior. Thus, identification of outcomes is more supported. | Privacy cynicism significantly (and negatively) influences privacy-protective behavior. It also reduces the effect of vulnerability and turns the negative relationship between benefits and protective behavior into a positive one. When response costs are low, only those with low levels of cynicism engage more in protective behaviors. | Using a wider variety of antecedents within the context of a moderation-based study. | |

| Wirth et al. [28]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 166 MTurk users). | Not stated. | PLS-SEM. | Social media self-disclosure as a function of moderated privacy risk perception. | A form of powerlessness, and resignation in terms of the effectiveness of privacy-protective behavior leading to fatigue, in turn, moderating the influences of perceived risk and benefits. | Privacy calculus. | Used a moderator between the privacy calculus constructs. Privacy burnout and increased willingness to self-disclose, thus identification of outcomes is more supported. | Privacy resignation acts as a significant (and strong) moderator within the context of perceived privacy risks as well as the benefits perceived when disclosing. | Using means to gauge actual disclosure; future research should investigate the relationship between privacy threats and risks, specifically within a wider variety of privacy contexts, by taking additional constructs into account including past privacy invasions and experience. | |

| Zhang et al. [21]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 1734 mobile app users). | China. | Propensity score matching (PSM). | WeChat self-disclosure. | The fatigue caused by the lack of privacy control as a result of privacy resignation. | Not used. | Used various control variables as moderators, thus identification of outcomes is more supported. Privacy burnout and increased willingness to self-disclose are outcomes as argued. | Privacy protective behavior is significantly less in individuals who suffer from privacy fatigue than those who don’t. This is the case regardless of gender, age, education frequency of use and number of WeChat friends. | Studying the same concept on a wider variety of platforms and corroborating the findings using other statistical techniques such as multigroup analyses. | |

| Zhu et al. [23]. | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey of 251 mHealth app users). | China. | PLS-SEM. | Self-disclosure via mHealth apps. | A negative psychologically-induced feeling of tiredness and exhaustion experienced when users are faced with increasingly complex privacy assurances and situations where very granular forms of personal information are to be shared to the extent that they feel a loss of control. | Multidimensional development theory, elaboration likelihood model. | Privacy policy effectiveness ***, privacy setting affordance ***. | No significant influence on increased willingness to self-disclose. | Significant reductions in privacy fatigue were observed as the privacy policy effectiveness and privacy setting affordances increase. However, fatigue did not result in increased disclosure which post hoc interview data indicate may be related to the low amount of cognitive cost incurred when using mHealth apps (as opposed to other apps such as social media). | Increase the demographic diversity of the sample including the inclusion of respondents from other countries. |

| Hoffmann et al. [16]. | Qualitative (focus groups with 96 internet users). | Germany. | Thematic analysis. | Internet use and online participation. | A form of cynical coping typified by feelings of powerlessness, mistrust, and uncertainty, as no amount of privacy-protective behavior is truly effective. | Not used. | Lack of knowledge, privacy concerns, privacy threat experience. | Mistrust, privacy burnout, increased willingness to self-disclose, powerlessness. | Findings indicate that privacy cynicism, as a function of fatigue, weakens the effect of concerns on privacy-protective behavior (as a moderator). | Studying the antecedents on a wider variety of platforms with a clear separation between institutional and noninstitutional privacy concerns. In other words, being able to understand how the breadth and depth of self-disclosure is influenced by a respondent’s level of cynicism (thus fatigue). Specific psychological coping mechanisms should be considered (e.g., Vaillant’s categorizations). |

| Hargittai and Marwick [15]. | Qualitative (focus groups with 40 university users). | US. | Thematic analysis. | Relationship between privacy attitudes and online behavior among internet users. | The cynical feeling that there is no amount of privacy-protective behavior that will be sufficient to prevent privacy invasions. | Not used. | Privacy concerns (social and not institutional). | Privacy apathy, increased willingness to self-disclose. | Focus group participants are aware of privacy risks, specifically social risks (i.e., personal conflict and embarrassment) as opposed to noninstitutional risks. Participants are aware of the distinction between different types of personal information. Networked privacy could prove difficult. Cynicism was clearly used as a coping mechanism to deal with the social nature of privacy invasion. | Further our understanding om how users negotiate social privacy boundaries as opposed to those institutional in nature. |

| Marwick and Hargittai [17]. | Qualitative (interviews and focus groups with 40 university students), quantitative (survey of 40 university students). | US. | Thematic analysis. | Institutional privacy risk when disclosing personal information online. | Fatigue as a cynical coping mechanism hinged on the fact that excessive privacy-protective behavior is futile as privacy invasions are inevitable. | Not used. | Privacy control complexity. | Privacy burnout, privacy resignation, privacy-based ontological dilemma, powerlessness. | Younger users find it difficult to use social media and other online resources without providing authentic information. There is an overwhelming feeling that users are resigned to the fact that their data has to be given in order to use the services they require and deem beneficial; no real choice is provided, and there the calculus does not apply. Ontological dilemma of sorts. In addition, privacy-protective behavior becomes irrelevant if you have nothing to hide. | Given the prominence of feelings that there is no real choice to use online apps and systems, what mechanisms could alleviate feelings of privacy resignation? To what extent do certain contexts moderate the level of fatigue experienced? |

| Oh et al. [24]. | Qualitative (interviews with 10 university students and staff). | South Korea. | Thematic analysis. | Privacy fatigue experienced as a result of privacy invasions when using IoT devices (smart home and smart healthcare). | Fatigue that results from user feelings that they have lost control over their personal information as a result of repeated privacy invasions. | Protection motivation theory. | Lack of knowledge, privacy policy cost, perceived severity of privacy invasion. | Privacy burnout, privacy resignation, powerlessness. | Participant sentiment that the personal information shared via the IoT devices is highly vulnerable and that no amount of self-coping could prevent privacy invasions. | Conduct the same study using a quantitative approach. |

References

- Weisburd, K. Sentenced to surveillance: Fourth Amendment limits on electronic monitoring. NCL Rev. 2019, 98, 717–777. [Google Scholar]

- Razi, A.; Agha, Z.; Chatlani, N.; Wisniewski, P. Privacy Challenges for Adolescents as a Vulnerable Population. In Proceedings of the Networked Privacy Workshop of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Grossklags, J. Privacy and rationality in individual decision making. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2005, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solove, D.J. The myth of the privacy paradox. Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 2021, 89, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y. The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 81, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.B.; Io, H.N.; Tang, H. Sentiments and perceptions after a privacy breach incident. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2050018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikgoz, F.; Vega, R.P. The Role of Privacy Cynicism in Consumer Habits with Voice Assistants: A Technology Acceptance Model Perspective. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, R. Contextualizing how teens manage personal and interpersonal privacy on social media. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 1058–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Dinev, T.; Willison, R. Why security and privacy research lies at the centre of the information systems (IS) artefact: Proposing a bold research agenda. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N. The Rise of Social Media and Its Impact on Mainstream Journalism; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Li, X.; Wang, G. Are You Tired? I am: Trying to Understand Privacy Fatigue of Social Media Users. In Proceedings of the Conference Proceedings/Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–5 May 2022; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3491101.3519778 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Rajaobelina, L.; Tep, S.P.; Arcand, M.; Ricard, L. Creepiness: Its antecedents and impact on loyalty when interacting with a chatbot. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 2339–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Marwick, A. “What can I really do?” Explaining the Privacy Paradox with online apathy. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2016, 10, 3737–3757. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, C.P.; Lutz, C.; Ranzini, G. Privacy cynicism: A new approach to the privacy paradox. Cyberpsychology 2016, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.; Hargittai, E. Nothing to hide, nothing to lose? Incentives and disincentives to sharing information with institutions online. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1697–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]