Insights into How Vietnamese Retailers Utilize Social Media to Facilitate Knowledge Creation through the Process of Value Co-Creation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Engagement through Social Media

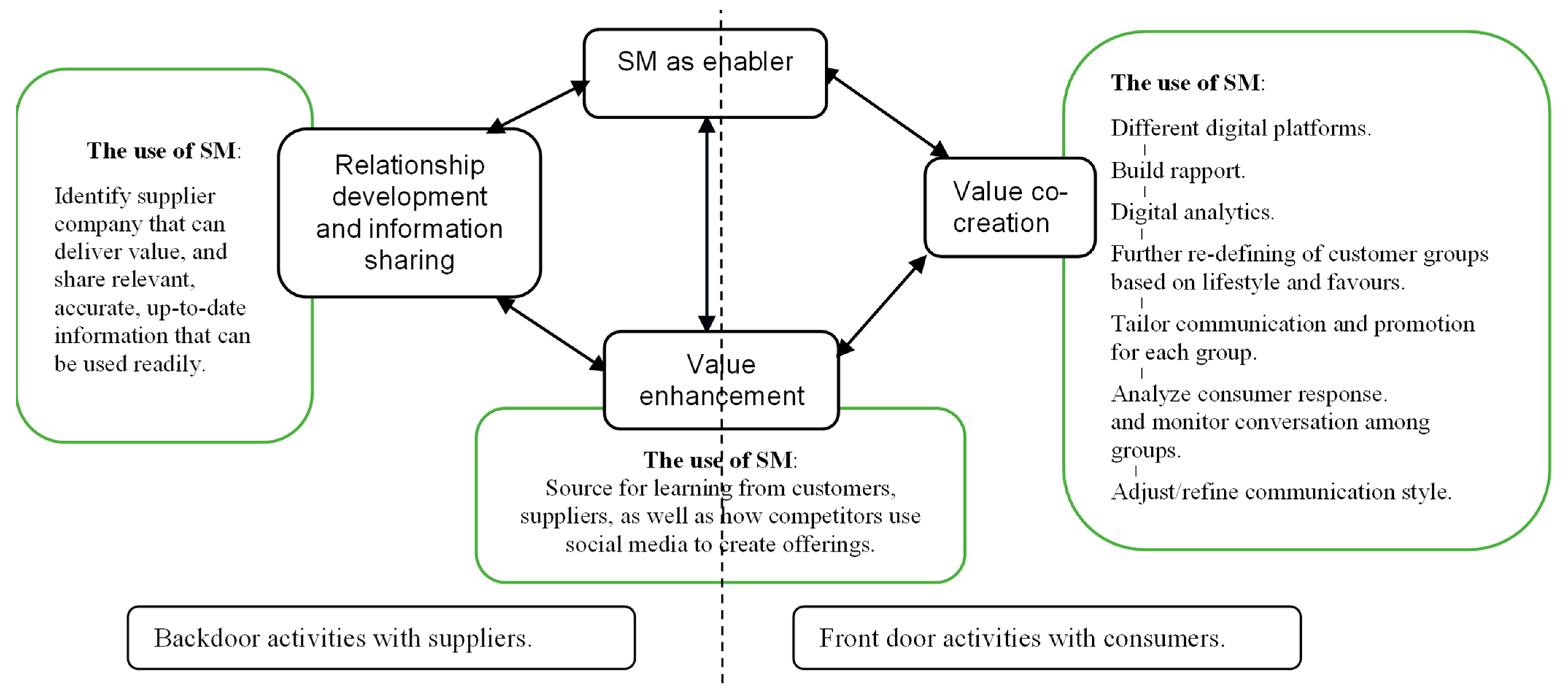

2.2. Enhancing Consumer Motivation

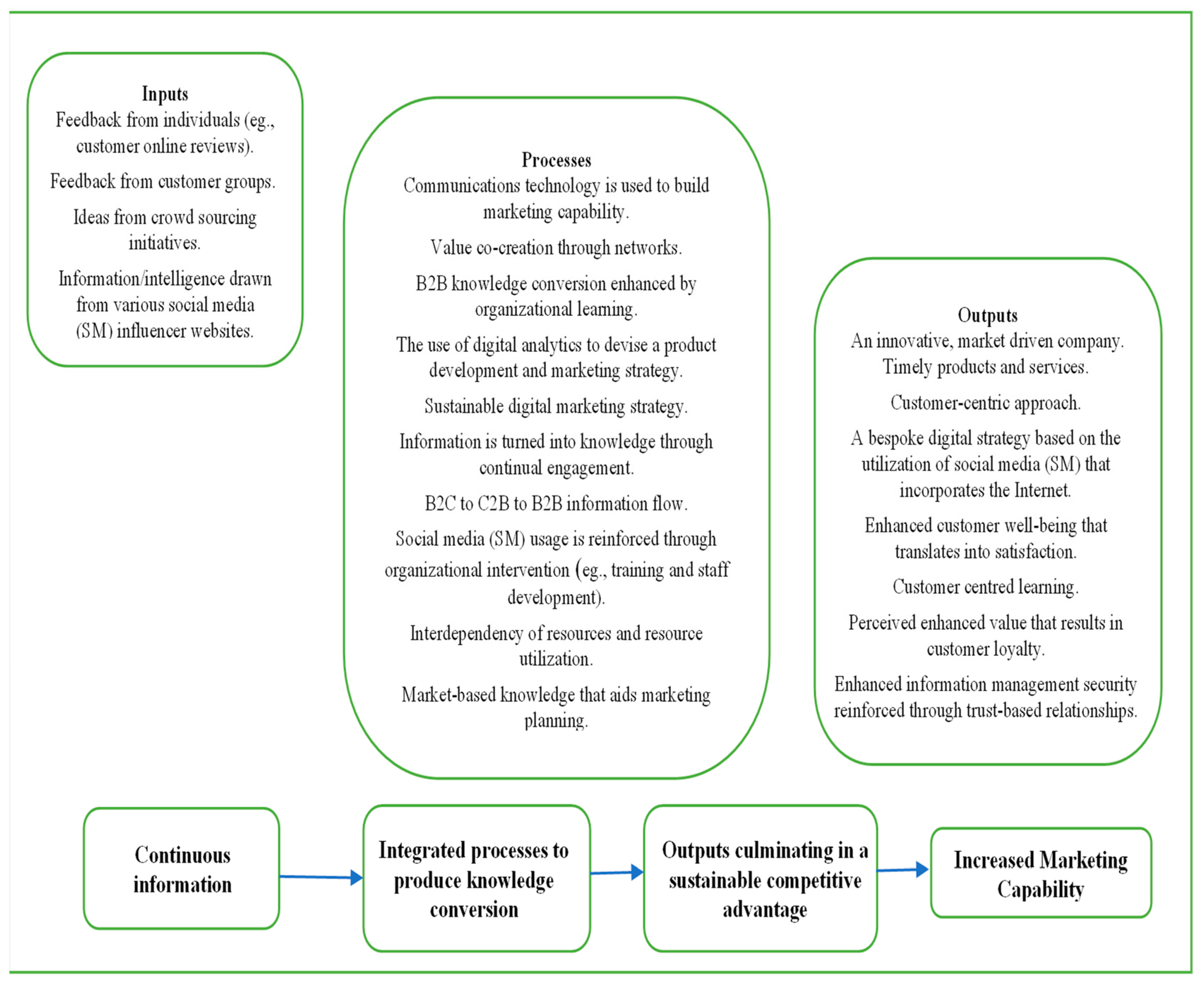

2.3. Knowledge Development and Utilization

3. Research Method

3.1. In-Depth Personal Interviews

3.2. Questionnaire Development

- What is the main advantage(s) of using social media to communicate with customers?

- Which social media channels do you use to communicate with customers (such as YouTube, Facebook, WhatsApp; LinkedIn twitter etc)?

- Which social media channel is the most suitable/successful and why?

- How is the data/information received through social media analysed?

- Do you share the results of the data analysis with your suppliers? If yes, please explain:

- Do you and your suppliers co-operate in terms of social media usage? If yes, please explain:

- Which aspects of customer service does social media usage support?

- When and at what time of the year is social media usage most effective?

- When is it not appropriate to use social media?

- How effective is the use of social media compared to other forms of communication?

- Does social media usage require special training and support? If yes, please explain:

- Do you use social media specialist companies to administer your social media activities (including social media site)? If yes, please explain:

- Do you monitor how other retailers use social media? If yes, please explain:

- Which aspects of supply chain management, does social media support and why?

- In the future, how do you see the usage of social media being extended?

3.3. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Managerial Implications

8. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lacka, E.; Chong, A. Usability perspective on social media sites’ adoption in the B2B context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studen, L.; Tiberius, V. Social Media, Quo Vadis? Prospective Development and Implications. Futur. Internet 2020, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.; Kohil, A.K.; Sahay, A. Market-driven versus driving markets. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2000, 28, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, M.D.; Narus, J.A.; Roehm, M.L.; Ritz, W. From transactions to journeys and beyond: The evolution of B2B buying process modeling. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Wang, F.; Elg, U.; Rosendo-Ríos, V. Market driving strategies: Beyond localization. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5682–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, G.; Grewal, L.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M.B.; Hepler, J.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Saul, L.; Jacobs, S.; Wilson, K.; Albarracín, D. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgurcu, B.; Cavusoglu, H.; Benbasat, I. Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical Study of Rationality-Based Beliefs and Information Security Awareness. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.S.; Jiang, M.; Alhabash, S.; LaRose, R.; Rifon, N.J.; Cotten, S.R. Understanding online safety behaviors: A protection motivation theory perspective. Comput. Secur. 2016, 59, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehrer, E.; Senecal, S.; Bolman, E. Sales force technology usage-Reasons, barriers and support: An exploratory investigation. Ind. Market. Manag. 2005, 34, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B. Exploring Chinese users’ acceptance of instant messaging using the theory of planned behavior, the technology acceptance model, and the flow theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussila, J.; Kärkkäinen, H.; Leino, M. Innovation-related benefits of social media in Business-to-Business customer relationships. Int. J. Adv. Media Commun. 2013, 5, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakainen, P.; Siponen, M. Improving Employees’ Compliance Through Information Systems Security Training: An Action Research Study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Ambient Awareness and Knowledge Acquisition: Using Social Media to Learn “Who Knows What” and “Who Knows Whom”. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swani, K.; Brown, B. The effectiveness of social media messages in organizational buying contexts. Am. Market. Assoc. 2011, 22, 519. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Trim, P.R.J. Enhancing Marketing Provision through Increased Online Safety That Imbues Consumer Confidence: Coupling AI and ML with the AIDA Model. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Consumer and Object Experience in the Internet of Things: An Assemblage Theory Approach. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 44, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Trim, P.R.J. Refining brand strategy: Insights into how the “informed poseur” legitimizes purchasing counterfeits. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Fisher, G.J.; Yang, Z. Organizational learning and technological innovation: The distinct dimensions of novelty and meaningfulness that impact firm performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 1166–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Hasford, J.; Turner, B.; Hardesty, D.M.; Zablah, A.R. Emotional Calibration and Salesperson Performance. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntürkün, P.; Haumann, T.; Mikolon, S. Disentangling the Differential Roles of Warmth and Competence Judgments in Customer-Service Provider Relationships. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggeveen, A.L.; Grewal, D.; Karsberg, J.; Noble, S.M.; Nordfält, J.; Patrick, V.M.; Schweiger, E.; Soysal, G.; Dillard, A.; Cooper, N.; et al. Forging meaningful consumer-brand relationships through creative merchandise offerings and innovative merchandising strategies. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelle, E. Introducing Media Richness into an Integrated Model of Consumers’ Intentions to Use Online Stores in Their Purchase Process. J. Internet Commer. 2009, 8, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, L.; Pancer, E.; Poole, M.; Deng, Q. Emoji, Playfulness, and Brand Engagement on Twitter. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 53, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J.G.; Garrity, C.P.; Rice, D.H. What Makes a Human Brand Authentic? Identifying the Antecedents of Celebrity Authenticity. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavra, D.; Namyatova, K.; Vitkova, L. Detection of Induced Activity in Social Networks: Model and Methodology. Future Int. 2021, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Vu, A.; Trim, P. Millennials and repurchasing behaviour: A collectivist emerging market. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Romero, G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Millennials’ use of online social networks for job search: The Ecuadorian case. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; von Krogh, G. Perspective—Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge Conversion: Controversy and Advancement in Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; Leung, W.K.S.; Ting, H. Investigating the role of social media marketing on value co-creation and engagement: An empirical study in China and Hong Kong. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Understanding Cultural Differences in Innovation: A Conceptual Framework and Future Research Directions. J. Int. Mark. 2014, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, S.O.; Agnihotri, R.; Dingus, R. Social media use in B2b sales and its impact on competitive intelligence collection and adaptive selling: Examining the role of learning orientation as an enabler. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 66, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A. Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bouwman, H. Orchestration and governance in digital platform ecosystems: A literature review and trends. Digit. Policy, Regul. Gov. 2019, 21, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Antecedents and consequence of social media marketing for strategic competitive advantage of small and medium enterprises: Mediating role of utilitarian and hedonic value. J. Strat. Mark. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Belk, R. Consumers’ technology-facilitated brand engagement and wellbeing: Positivist TAM/PERMA- vs. Consumer Culture Theory perspectives. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Marketing in Computer-Mediated Environments: Research Synthesis and New Directions. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, M.; Kumar, V.; Harmeling, C.; Singh, S.; Zhu, T.; Chen, J.; Duncan, T.; Fortin, W.; Rosa, E. Insight is power: Understanding the terms of the consumer-firm data exchange. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.A.; Sinha, R.K. Brand Communities and New Product Adoption: The Influence and Limits of Oppositional Loyalty. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, J.F.; Carvalho, S.W. Consumers’ love for technological gadgets is linked to personal growth. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 194, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Meadows, M.; Wong, D.; Xia, S. Understanding consumers’ social media engagement behaviour: An examination of the moderation effect of social media context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Borah, A.; Palmatier, R.W. Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesgin, M.; Murthy, R.S. Consumer engagement: The role of social currency in online reviews. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 609–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, D.; Bodapati, A.V.; Puccinelli, N.M.; Tsiros, M.; Goodstein, R.C.; Kushwaha, T.; Suri, R.; Ho, H.; Brandon, R.; Hatfield, C. Retailer Marketing Communications in the Digital Age: Getting the Right Message to the Right Shopper at the Right Time. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V. It’s about human experiences… and beyond, to co-creation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F.; MacLachlan, D.L. Responsive and Proactive Market Orientation and New-Product Success. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2004, 21, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, P.J.; Purchase, S. Managing collaboration within networks and relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trim, P.R.J.; Lee, Y.-I. How B2B marketers interact with customers and develop knowledge to produce a co-owned marketing strategy. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ketchen, D.J.; Nichols, E.L. Organizational learning as a strategic resource in supply management. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Yates, J. It’s About Time: Temporal Structuring in Organizations. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, N.; Story, V.M.; Cadogan, J.W.; Micevski, M.; Kadić-Maglajlić, S. Firm Innovativeness and Export Performance: Environmental, Networking, and Structural Contingencies. J. Int. Mark. 2013, 21, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Lyles, M.A.; Tsang, E.W.K. Inter-Organizational Knowledge Transfer: Current Themes and Future Prospects. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, S. Cultural Knowledge in Organizations: Exploring the Collective Mind; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, H.; Waluszewski, A. Developing a new understanding of markets: Reinterpreting the 4Ps. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2005, 20, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, Z.; Mourali, M. Consumer Adoption of New Products: Independent versus Interdependent Self-Perspectives. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, H.A.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Zablah, A.R. Gratitude versus Entitlement: A Dual Process Model of the Profitability Implications of Customer Prioritization. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Palmatier, R.W.; Scheer, L.K.; Li, N. Trust at Different Organizational Levels. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, C.J. Interaction in business relationships: A time perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, D.B.; Wittmann, C.M. Improving marketing success: The role of tacit knowledge exchange between sales and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes. Public Opin. Q. 1960, 24, 163–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydén, P.; Ringberg, T.; Wilke, R. How Managers’ Shared Mental Models of Business–Customer Interactions Create Different Sensemaking of Social Media. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vgena, K.; Kitsiou, A.; Kalloniatis, C.; Gritzalis, S. Determining the Role of Social Identity Attributes to the Protection of Users’ Privacy in Social Media. Futur. Internet 2022, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Bonezzi, A.; De Angelis, M. Sharing with Friends versus Strangers: How Interpersonal Closeness Influences Word-of-Mouth Valence. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J.; Neeley, S.E. Customer Relationship Building on the Internet in B2B Marketing: A Proposed Typology. J. Mark. Theory Pr. 2004, 12, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trim, P.R.J.; Jones, N.A.; Brear, K. Building organisational resilience through a designed-in security management approach. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2009, 3, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, L.; Dibb, S.; Simkin, L.; Canhoto, A.; Analogbei, M. Troubled waters: The transformation of marketing in a digital world. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 2103–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishen, A.S.; Leenders, M.A.A.M.; Muthaly, S.; Ziółkowska, M.; LaTour, M.S. Social networking from a social capital perspective: A cross-cultural analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1234–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Guangju, W.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Ilyas, Z.; Mustafa, G.; Jianzhou, Y. Consumers’ online information adoption behavior: Motives and antecedents of electronic word of mouth communications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, D.; Choi, S. Social embeddedness of persuasion: Effects of cognitive social structures on information credibility assessment and sharing in social media. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Mannan, M. Consumer online purchase behavior of local fashion clothing brands: Information adoption, e-WOM, online brand familiarity and online brand experience. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Andersen, K.R. Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: A global expert study on sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.P.-J.; Straub, D.W.; Liang, T.-P. How information technology governance mechanisms and strategic alignment influence organizational performance: Insights from a matched survey of business and IT managers. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Characteristics (1 = Most Cited and 5 = Least Cited) |

|---|---|---|

| The Effectiveness of Social Media | The way in which supply chain management is supported by SM | (1=) Accuracy of information to customers (1=) Accuracy of information to suppliers (3=) Searching for new customers (3=) Searching for new suppliers |

| The main advantages of SM |

| |

| Frequently used SM channels |

(5=) Lazado (5=) Tiki (5=) WhatsApp (5=) WeChat | |

| How Social Media Supports Marketing Intelligence | The use of SM vis-a-vis supporting marketing intelligence |

(2=) Managing customer relationships |

| Information sharing is used |

(2=) To meet seasonal demands | |

| The objective is seller–buyer cooperation |

| |

| Monitoring other retailers |

| |

| How Social Media Supports Customer Service | Effectiveness of SM compared with other forms of communication |

(4=) Ability to interact speedily with suppliers |

| The timing of the usage of social media | Daily basis:

| |

| Inappropriate timing of social media usage |

| |

| SM supports customer service |

| |

| Extending social media applications |

| |

| The Knowledge & Skill Needed for Social Media | Special training and support |

|

| Use of SM specialist companies | (1=) Launching promotions (1=) Online promotion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trim, P.R.J.; Lee, Y.-I.; Vu, A. Insights into How Vietnamese Retailers Utilize Social Media to Facilitate Knowledge Creation through the Process of Value Co-Creation. Future Internet 2023, 15, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15040123

Trim PRJ, Lee Y-I, Vu A. Insights into How Vietnamese Retailers Utilize Social Media to Facilitate Knowledge Creation through the Process of Value Co-Creation. Future Internet. 2023; 15(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrim, Peter R. J., Yang-Im Lee, and An Vu. 2023. "Insights into How Vietnamese Retailers Utilize Social Media to Facilitate Knowledge Creation through the Process of Value Co-Creation" Future Internet 15, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15040123

APA StyleTrim, P. R. J., Lee, Y.-I., & Vu, A. (2023). Insights into How Vietnamese Retailers Utilize Social Media to Facilitate Knowledge Creation through the Process of Value Co-Creation. Future Internet, 15(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15040123