School Culture and Digital Technologies: Educational Practices at Universities within the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Higher Education and the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.2. The Case of the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana in Mexico and Its Contingency Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.3. School Culture in the University Educational Context

- The material–economic agreement: this first practice relates to the resources that make it possible for activities to take place; it develops the dimension of a given space-time. It enables and restricts the practices; it comprises resources and spaces (such as a classroom, a playground, school furniture, virtual classroom), digital technology, etc. This dimension makes educational acts and events possible.

- The cultural-discursive agreement: this practice is the dimension of language and meanings; therefore, it also regulates other practices such as the fact of expressing oneself in a certain way in a certain place of the fact of being able to share the same specialized language of a discipline, which requires the speakers know it. This dimension makes conversation possible.

- The socio-political agreement: this kind of practice regulates relations between people and interactions with objects, in a family, in a virtual classroom, and in a school. This dimension makes social relations possible.

1.4. Research from Educational Practice as a Catalyst for Pedagogical Transformation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus of the Methodological Approach

2.2. Educational Actors

- -

- Professors: the professors at this university are hired under the research professor scheme, in which half of their time is dedicated to education, and the other half is dedicated to research. At UAM-C, 89.9% of professors are full-time, and 60.6% have doctoral studies.

- -

- Managers: the managers of the institution are professors elected by the divisional and academic councils. Their term as managers in the university lasts 4 years.

- -

- Students: the students of the UAM-C are characterized by belonging to middle and medium–low economic sectors. A total of 38.5% of them come from within Mexico, 50.4% have studied in public schools, and 45% are women and 55% are men.

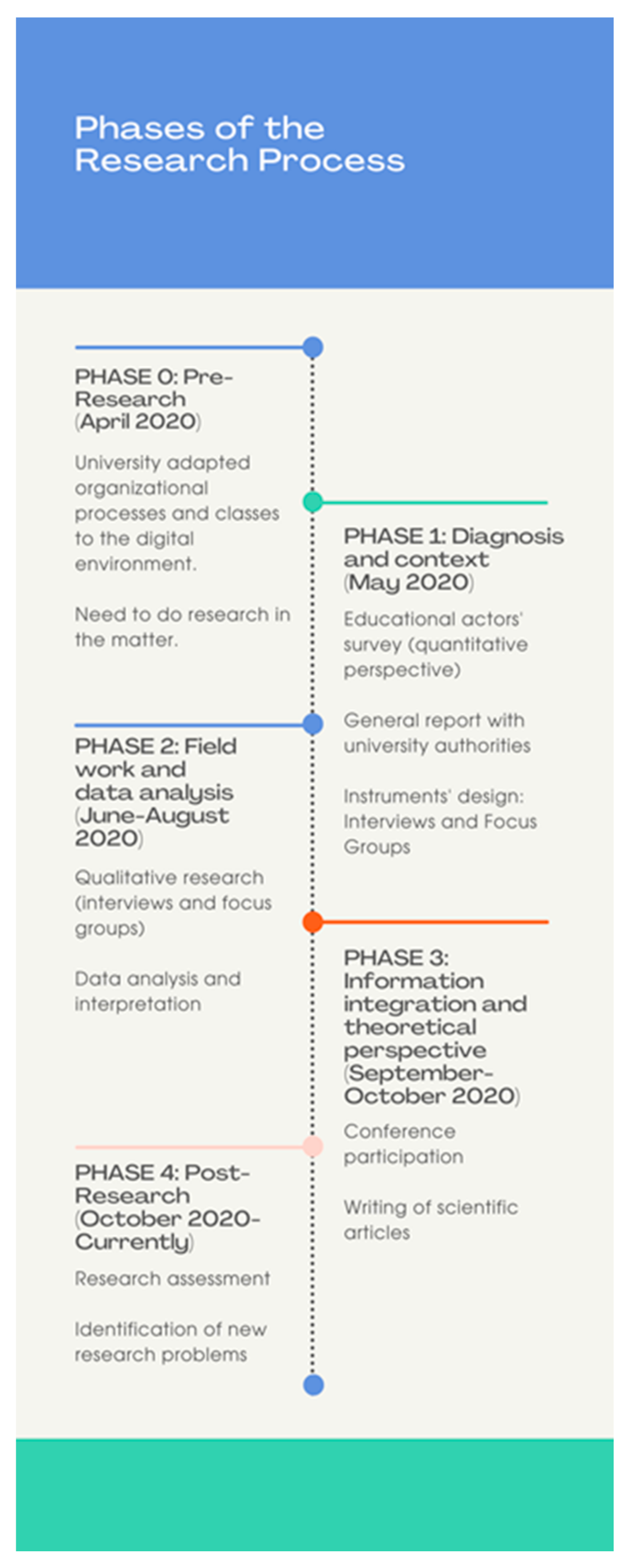

2.3. Research Procedures

3. Results

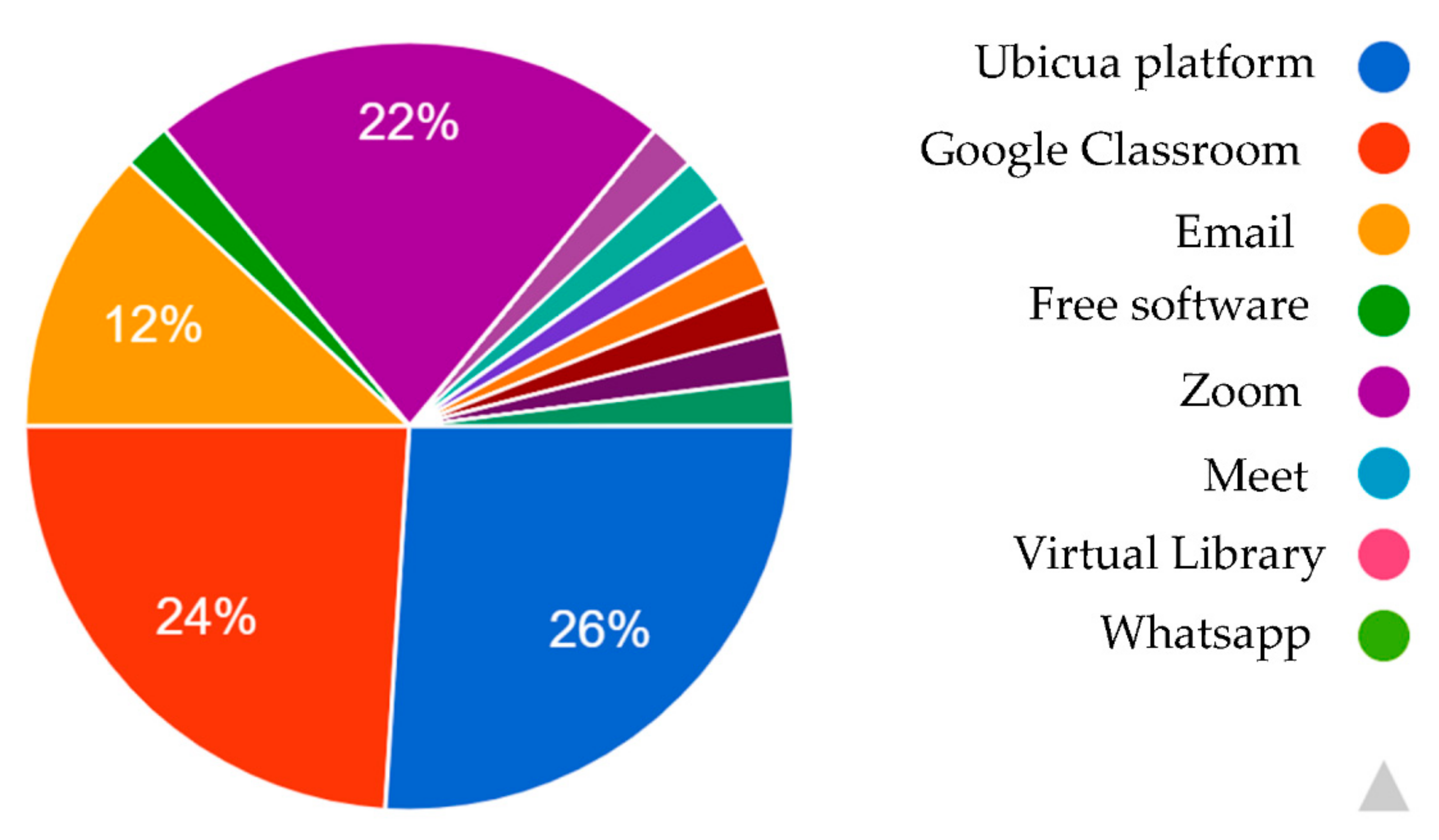

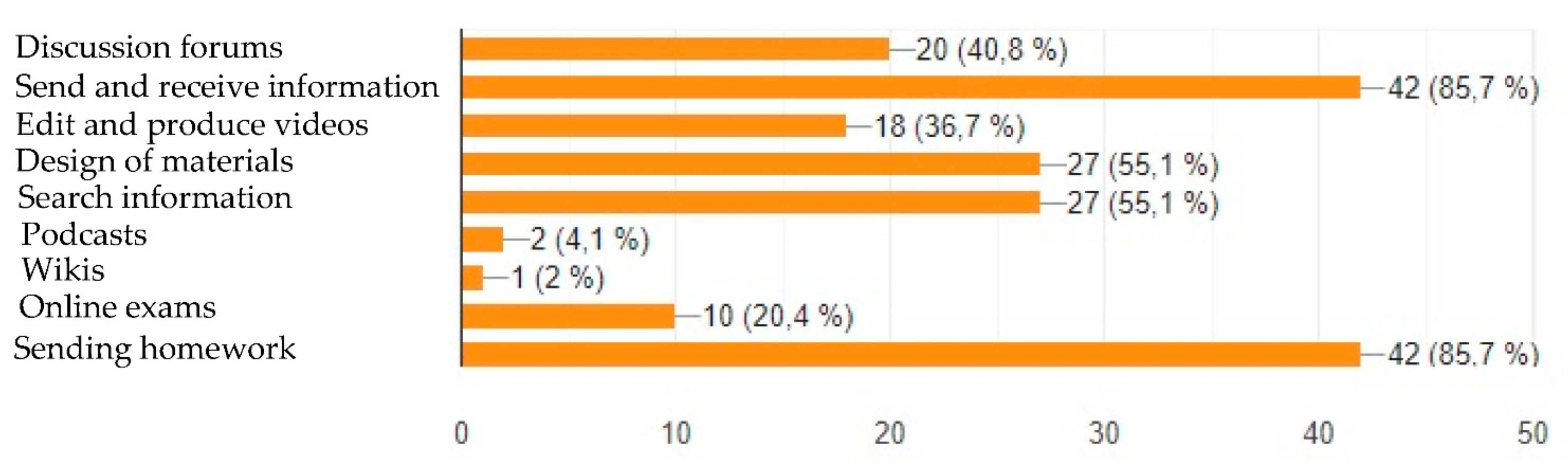

3.1. Quantitative Perspective Results

3.1.1. Students

3.1.2. Professors and Managers

3.2. Qualitative Perspective Results

- (a)

- The material–economic agreement (educational acts and deeds)

| Perspective/Evaluation | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths (positive) | Competences of the distance learner | Developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes for distance learning |

| Class structure | Class structure and didactic sequence that makes the teaching–learning process possible | |

| Technological platforms | Practices in technological platforms that make the teaching–learning process possible | |

| Redefining processes | Positive assessment of new roles within the university | |

| Role of the university | Positive assessment of the university’s role in the context of the pandemic | |

| Weaknesses (negative) | Socio-digital divide | Significant differences of educational actors in accessing information and communication technologies |

| University bureaucracy | Administrative processes that hinder the university’s substantive functions | |

| Competences of the distance learner | Lack of knowledge, skills, and attitudes to distance learning | |

| Class structure | Class structure and didactic sequencing that hinder the teaching–learning process | |

| Technological platforms | Practices on technology platforms that hinder the teaching–learning process | |

| Environmental problems | Environmental conditions that hinder the teaching–learning process |

- (b)

- The cultural-discursive agreement (conversations—language perspective)

| Perspective/Evaluation | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strength (positive) | Communication platforms | Effective communication practices in information technology and communication-mediated education |

| Weakness (negative) | Communication noise | Undesirable factors hindering communication in ITC-mediated education |

- (c)

- The socio-political agreement (social relations)

| Perspective/Evaluation | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths (positive) | Empathy | Acknowledgment of the characteristics, needs, and problems of other educational actors |

| Teaching role | Professor relationships with students and managers that enable the teaching–learning process | |

| Weaknesses (negative) | Personal effects | Social relations inside and outside the university that hinder the teaching–learning process |

| Teaching role | Professor relationships with pupils and students that hinder the teaching–learning process | |

| Collegial work | Lack of collegial work between educational actors to achieve common objectives |

3.3. Overall Results

3.3.1. Students

3.3.2. Professors

3.3.3. Managers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Covid-19 and Higher Education: Today and Tomorrow. 2020. Available online: http://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-EN-090420-2.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Paredes-Chacín, A.; Inciarte, A.; Walles-Peñaloza, D. Educación superior e investigación en Latinoamérica: Transición al uso de tecnologías digitales por Covid-19. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, XXVI, 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara Santuario, A. Educación superior y Covid-19: Una perspectiva comparada. In IISUE. Educación y Pandemia. Una Visión Académica; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; pp. 75–82. Available online: http://www.iisue.unam.mx/nosotros/covid/educacion-y-pandemia (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Salinas Ibáñez, J. Educación en tiempos de pandemia: Tecnologías digitales en la mejora de los procesos educativos. Innov. Educ. 2020, 22, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. Online and Remote Learning in Higher Education Institutes: A Necessity in light of COVID-19 Pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 2020, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, H.; Junior, F. La educación en tiempos de pandemia: Los desafíos de la escuela del siglo XXI. Rev. Arbitr. Cent. Investig. Estud. Gerenc. 2020, 44, 176–187. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grande-de-Prado, M.; García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Corell Almuzara, A.; Abella-García, V. Evaluación en Educación Superior durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Campus Virtuales 2020, 10, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Eynon, R.; Potter, J. Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, J.; Ralph, R.; Forde, K. Pandemic designs for the future: Perspectives of technology education teachers during COVID-19. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Castillo, L. Lo que la pandemia nos enseñó sobre la educación a distancia. Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Educ. 2020, L, 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Román, J.A. La educación superior en tiempos de pandemia: Una visión desde dentro del proceso formativo. Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Educ. 2020, L, 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ordorika, I. Pandemia y educación superior. Rev. Educ. Super. 2020, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Edwards-Groves, C.; Hardy, I.; Grootenboer, P.; Bristol, L. Changing Practices, Changing Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UAM. Legislación Universitaria. 2021. Available online: http://www.uam.mx/legislacion/LEGISLACION-UAM-ABRIL-2021/LEGISLACION-UAM-ABRIL-2021-COMPLETO.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Silva-López, R.B.; González-Nieto, N.A.; Cruz-Miguel, E.; Silva-López, M.I.; Hernández Pérez, J.E. Estrategias de enseñanza-aprendizaje y acompañamiento para la educación virtual: PEER en la UAM-Lerma. In Prácticas Educativas de la UAM Lerma: Del Aula Física al Aula Digital; Silva-López, R.B., Hernández-Razo, O.E., García-Garibay, J.M., Eds.; Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, Unidad Lerma: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; pp. 10–42. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana. Programa Emergente de Educación a Distancia. Available online: https://www.uam.mx/educacionvirtual/uv/peer.html (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Julia, D. La cultura escolar como objeto histórico. In Historia de las Universidades Modernas en Hispanoamérica. Métodos y Fuentes; Menegus, M., González, E., Eds.; Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Viñao Frago, A. Historia de la Educación e Historia Cultural: Posibilidades, Problemas, Cuestiones. Revista de Educación. Nº 306. La Profesión Docente. 1995; pp. 245–269. Available online: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/detalle.action?cod=494 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Escolano Benito, A. La escuela como construcción cultural. El giro etnográfico en la historiografía de la escuela. Espac. Blanco. Rev. Educ. 2008, 18, 131–146. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=384539800006 (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Bourdieu, P. Los Herederos: Los Estudiantes y la Cultura; Siglo XXI: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, H. El Estudio de Caso: Teoría y Práctica; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Loaiza-Aguirre, M.I.; Zúñiga-Ojeda, A.; Portuguez-Castro, M. Characterization of the Teaching Profile within the Framework of Education 4.0. Future Internet 2021, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. Anticipating the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century; Routledge-UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Passeron, J.C. La teoría de la reproducción social como una teoría del cambio: Una evaluación crítica del concepto de “con-tradicción interna”. Estud. Sociol. 1983, I, 417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Beane, M.; Apple, M. Escuelas Democráticas; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston, J. Professor Decision-Making in the Classroom: A Collection of Papers; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Instrument | Educational Actors | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative surveys | Students | 254 |

| Professors | 46 | |

| Semi-structured interviews | Students | 01 |

| Professors | 06 | |

| Managers | 04 | |

| Focus groups | Students obtaining a Bachelor’s Degree in Communication Sciences | 06 |

| Students obtaining a Bachelor’s Degree in Information Systems and Technology | 06 | |

| Students obtaining a Master’s Degree in Design, Information and Communication | 06 |

| Types of Learning | Very Good | Good | Average | Bad | There Was No Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you consider that your theoretical learning during the quarter was… | 10% | 36% | 37% | 15% | 2% |

| Do you consider that your procedural learning (programming, editing, mockups, taking a picture, prototyping, researching…) was… | 8% | 35% | 42% | 10% | 5% |

| Do you consider that the learning in attitudes and values (organization of time, self-study, discipline, punctuality, cooperation, etc.) was… | 12% | 47% | 32% | 8% | 1% |

| Material–Economic Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perspective/Evaluation | Educational actors | ||

| Students | Professors | Managers | |

| Strength (Positive) | 53 | 37 | 39 |

| Weakness (Negative) | 61 | 13 | 24 |

| Cultural-Discursive Agreement | |||

| Perspective/Evaluation | Educational actors | ||

| Students | Professors | Managers | |

| Strength (Positive) | 18 | 16 | 13 |

| Weakness (Negative) | 13 | 2 | 6 |

| Socio-Political Agreement | |||

| Perspective/Evaluation | Educational actors | ||

| Students | Professors | Managers | |

| Strength (Positive) | 33 | 29 | 32 |

| Weakness (Negative) | 25 | 6 | 16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Nieto, N.A.; García-Hernández, C.; Espinosa-Meneses, M. School Culture and Digital Technologies: Educational Practices at Universities within the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Future Internet 2021, 13, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13100246

González-Nieto NA, García-Hernández C, Espinosa-Meneses M. School Culture and Digital Technologies: Educational Practices at Universities within the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Future Internet. 2021; 13(10):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13100246

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Nieto, Noé Abraham, Caridad García-Hernández, and Margarita Espinosa-Meneses. 2021. "School Culture and Digital Technologies: Educational Practices at Universities within the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Future Internet 13, no. 10: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13100246

APA StyleGonzález-Nieto, N. A., García-Hernández, C., & Espinosa-Meneses, M. (2021). School Culture and Digital Technologies: Educational Practices at Universities within the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Future Internet, 13(10), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13100246