Abstract

Building upon the perspectives of social capital theory, social support, and experience, this study developed a theoretical model to investigate the determinants of subjective well-being on social media. This study also examined the moderating role of experience on the relationship between subjective well-being and social support. Data collected from 267 social media users in Taiwan were used to test the proposed model. Structural equation modeling analysis was used to test the measurement model and the structural model. The findings reveal that receiving online support and providing online support are the key predictors of subjective well-being. Furthermore, social capital positively influences the reception and provision of online support. Finally, providing online support has a significant effect on the subjective well-being of users with low levels of use experience, while receiving online support exerts a stronger influence on the subjective well-being of users with high levels of use experience.

1. Introduction

With increasing popularity, social media (e.g., virtual communities, weblogs, wiki, and social networking sites) has become a useful channel for socializing [1,2,3]. It enables people to create and maintain their social networks regardless of the limitation of geographic location [4,5]. People build their online social networks to satisfy their needs for social support [1]. Online social support could help social media users to solve their problems, effectively manage stress, and mitigate the impact of negative life events [6]. As such, the proper use of social media can enhance users’ quality of life and facilitate subjective well-being [1,7].

Subjective well-being is a key factor that maintains users’ continuance intention toward information technologies, including social media [8]. Understanding the effect of social media use on subjective well-being has become increasingly critical in information systems (IS) research. Existing studies have examined the link between social capital and subjective well-being [7,8], as well as the influence of receiving social support on one’s quality of life [9]. These studies have provided valuable insights into the nature of social capital; close connections with others allows users to obtain information and support from others [7,10]. Furthermore, receiving online support from others may facilitate one’s subjective well-being [7]. In this sense, social support may mediate the relationship between social capital and subjective well-being. However, only a few studies have explored the relationships among social capital, online social support, and subjective well-being on social media.

Online support generally involves two distinct types of activity: seeking online support and providing online support [11]. Little attention has been paid to the effects of various types of online social support on users’ perceptions of well-being. In addition, the perception of well-being derived from social media use reflects one’s subjective evaluations of his/her cognition and perception of social media use at a static point [7,12]. In fact, an individual’s cognition and perception may change when his/her experience of information technology usage increases over time [13]. Therefore, the influence of online support activities on subjective well-being may vary as one’s use experience increases. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have been carried out to explore the moderating role of experience on the link between subjective well-being and online social support.

To address this research gap, we developed a research model by integrating the perspectives of social capital theory, social support, and experience. Based on the assertions of previous the literature [11,14], we hypothesize that social support on social media can be divided into two different types: receiving online support and providing online support. We then argue that the two types of social support can enhance subjective well-being, based on the previous literature on social support (e.g., [11,15,16]). We also propose that social capital impacts these two types of social support, based on the standpoint of [14], that people with higher levels of social relationship are more likely to get help from others and help others in a social unit. Additionally, we employ experience as a moderator in the model. We propose that providing online support exerts a stronger effect on the subjective well-being of users with less experience, while receiving online support will have a greater impact on the subjective well-being of users with more experience.

This study contributes to social media research in two ways. First, we demonstrate that social capital does increase the development of online support activities, which in turn enhances users’ subjective well-being. Second, by applying the viewpoint of experience, we further illustrate how experience of social media usage impacts the relationship between social support and subjective well-being. This paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature relevant to social capital theory, social support, subjective well-being, and experience. Then, we discuss the developed research model and propose relevant research hypotheses. In the third and fourth sections, we describe the research methodology and present our data analyses results. In the fifth section, we discuss the research findings, the theoretical contributions, the practical implications, and the limitations of the study.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Subjective Well-Being and Social Media

Well-being is a subjective and related concept that represents one’s positive self-appraisal about his/her life at a point or period [7,12,17]. Self-appraisal includes one’s emotional reactions, moods, judgements about their life satisfaction, and fulfillment [12]. In this sense, previous studies consider well-being as the contentment, satisfaction, or happiness derived from optimal psychological functioning [17,18]. On the other hand, some researchers suggest that well-being reflects one’s sense of pleasure and accomplishment value based on one’s overall evaluation of one’s quality of life [19]. Karademas (2007) [20] also postulates that well-being represents one’s positive mood, negative mood, and life satisfaction. Since previous the literature [7,8] argues that communication technologies such as social media can enhance users’ life quality and subjective well-being, in this study, we use the term “subjective well-being” to measure one’s feelings and consciousness about social media use, such as pleasure perception, life satisfaction, and positive affective reactions.

According to the expectancy theory of motivation [21], an individual’s behavior could be motivated by the desirability of the outcomes [22]. Subjective well-being has been defined as the expected benefits that could motivate members to continue using social media [8]. Given that continued use determines the success of information technologies [13], such as social media, it is important to understand what can facilitate subjective well-being on social media. In fact, researchers have begun to explore the antecedents of subjective well-being. For example, [7] have found that social integration, social bonding, and social bridging are the antecedents of subjective well-being. Furthermore, [8] have reported that structural capital, relational capital, and cognitive capital are the predictors of subjective well-being.

Although previous studies [7,8] have demonstrated that social capital plays an important role in shaping subjective well-being, the factors affecting subjective well-being must be further clarified, because there are unexamined factors that may affect subjective well-being. Generally speaking, social media provides an attractive space for people to get or offer help [23]. Previous literature argues that receiving social support is a vital factor that determines subjective well-being in an organization [11,16,24]. However, it is unclear whether providing support to others in an online setting facilitates subjective well-being. In addition, researchers consider that the interpersonal relationships in a social unit will impact users’ online support-seeking and online support-providing behaviors [14]. Based on the above arguments, we recognize that interpersonal relationships affect receiving and providing online support, which in turn impacts subjective well-being. However, such relationships among interpersonal relationships, social support, and subjective well-being have received little attention from researchers. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to examine the links among social capital, social-support activities, and subjective well-being.

In addition, subject well-being is the scientific analysis of how an individual evaluates his/her life at a specific moment or period, as mentioned earlier. This implies that one’s perception of well-being may be different during various periods, since the relationships between subjective well-being and its antecedents may change as online contacts increase over time. However, such potential exchanges in the relationships between subjective well-being and its antecedents have been overlooked by previous studies. To fill this knowledge gap, this study aimed to examine the influence of experience on the relationship between online support activities and subjective well-being.

2.2. Social-Support Activities and Subjective Well-Being

Social support refers to the resources provided by others in a social group [15,25]. Researchers also define social support as one’s perception of being cared for, being responded to, and being helped by others in his/her social group [1,26,27]. By synthesizing these definitions, we recognize that social support involves resource exchange (e.g., tangible and intangible resources) between at least two persons in a social group [11,28].

The previous literature argues that people need emotional, informational, and tangible support to help them overcome stress [1,29]. Informational support refers to providing knowledge to solve others’ problems, while emotional support refers to expressing one’s concerns (e.g., caring and empathy) that could be indirectly helpful for others to solve problems [1]. On the other hand, tangible support refers to providing tangible goods or services for solving others’ problems [1]. In the social media context, users usually need others’ knowledge, experiences, and recommendations to help them to solve their problems [1]. They also need emotional support and encouragement to help them to deal with physical/mental problems and to cope with the stress of life changes [23]. Users may seek instrumental aid to solve their problems, as well [11]. Therefore, in this study, we considered that social support reflects the activities through which resources (e.g., information, emotional concerns, and tangible goods) will be delivered by supporters to those in need.

In addition, the success of social network services (SNSs) depends largely on intensive interaction among users, including seeking support and offering support [11]. Based on the nature of social support, social support in a social unit usually involves two different types of activities: receiving support and providing support [11,14]. In this study, we further focus on the two types of social support to reflect an individual’s perception about how much help and support he/she can receive from others and the extent of an individual’s involvement in providing help and support to others on social media.

In this study, social-support activities were expected to positively impact subjective well-being. The previous literature suggests that one of the major motivations for people to use social media is to get help and receive emotional support [1]. Receiving helpful social support in a social unit has been considered a vital predictor of subjective well-being [7], since social support is a coping resource that helps people overcome stress and provides necessary resources for resolving a problem [16]. Moreover, [1] argue that receiving support from others brings warmth to people’s hearts and helps fulfill their social needs; thus, an individual’s perception of well-being can be enhanced. By synthesizing the above arguments, we propose that receiving online support from others positively impacts subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Receiving online support is positively related to subjective well-being.

Users of social media tend to help others or respond to other’s needs, because they expect to receive important rewards [23]. For example, [30] found that users of a virtual community will help others if they feel that contributing helpful knowledge to others can enhance their professional reputations or make them feel good (i.e., enjoy helping). [31,32] posit that self-development, altruism, and enjoyment are important factors determining users’ content-contribution behavior in virtual communities. According to the uses and gratifications theory, people will seek gratification through technology use based on their needs [31]. In this sense, users who help others on social media may feel satisfied when they receive the expected rewards. The previous literature further argues that fulfilling human needs and the satisfaction of achieving goals are the basic tenets of subjective well-being [17]. Accordingly, we may expect that providing online support facilitates a user’s subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Providing online support is positively related to subjective well-being.

2.3. Social Capital and Social-Support Activities

Social capital refers to a set of actual and potential resources rooted in the relationships of an individual in a social unit [10]. On the other hand, researchers posit that social capital represents an environment of trust and shared resources of networks based on the social associations established in a voluntary manner [33,34]. As such, social capital has been considered a vital factor that can drive people to engage in social exchange behaviors (e.g., knowledge contribution) [35]. Previous literature has found that people with more social relationships will be more likely to provide support in the context of social media [36]. Therefore, this study considered social capital as a factor that may determine individuals’ social-support activities.

Social capital is a complex construct that can be classified into different dimensions [10,37,38]. In general, three key aspects can be used to represent social capital: identification, trust, and norms [10,35]. Identification occurs when individuals see themselves as being grouped with others in a social unit [38]. while trust is defined as one party’s willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another [6]. Norms, on the other hand, refer to the norms that facilitate an individual’s behavior (e.g., knowledge sharing) in an organization [35]. In the context of social media, providing and receiving support are voluntary; therefore, norms may not be the major antecedent that determines users’ social-support activities. The previous literature also agrees that social capital exists when people in a social unit experience strong identification and trust [30,38]. Therefore, identification and trust can be recognized as the key dimensions of social capital. Furthermore, researchers have argued that a higher-order construct can be employed to provide a more coherent description of the multiple facets of a complex phenomenon [39,40]. The previous literature has used second-order models to examine the influence of social capital on an individual’s behavior, as well (e.g., [41]). Thus, we conceptualize social capital as a second-order construct that includes the dimensions of identification and trust.

Social capital theory suggests that relationships embedded in a network create greater access to resources [42]. Thus, benefits could be extracted from these social relationships. The aspect of social capital has been used to explain various pro-social behaviors, such as knowledge sharing (e.g. [6,43]) and offering social support [11]. Previous literature suggests that identification is essential in facilitating resource exchange in online settings (e.g., [8,11,44]. Strong identification will enable users to be concerned with the outcome of a social unit rather than their own efforts and losses [35]. Users in a social unit may display altruistic behaviors [11,45] and act in the best interest of users in the social unit [11,45,46]. Therefore, it is expected that users with strong identification will be more likely to engage in social-support activities.

In addition, trust is also crucial for motivating people to engage in cooperative interactions [10,44,46,47] especially in an environment without workable rules to ensure others will behave in a socially acceptable manner [5], such as social media. The previous literature has also provided empirical evidence to support the effect of trust on getting help and giving help in the online context [4]. Based on the above arguments, we expect social capital to have a significant impact on online support activities.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Social capital is positively related to receiving online support.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Social capital is positively related to providing online support.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Experience

Experience is a critical factor that has an important influence on some key constructs and relationships (e.g., [48,49]), because experience increases one’s understanding about the actual performance of a service or an information technology [13]. According to the self-perception theory [13,50], an individual will adjust his/her perceptions by observing the outcome of focal behavior, and the adjusted perceptions will impact subsequent behaviors. Researchers also find that social support will be facilitated when one’s online contacts increase over time [25,51]. Accordingly, we propose that the influence of online support on subjective well-being may change as experience increases over time.

According to [25], the size of a social network in an online setting is related to one’s perception of social support and thus affects his/her perception of well-being. This implies that users may not obtain sufficient help and support from others, as a result of being in a small-sized social network and having weak online social ties at the beginning of social media usage. In addition, from the viewpoint of the social exchange theory [52], helping others and responding to others’ needs in the online context could be considered a social investment [23], as people expect that they could receive help from others in the future [35,53]. This means that helping others is particularly important for users with low levels of experience, because it will allow them to increase self-identity and thus increase social interactions with others, to receive help from others in the future. Based on the aforementioned arguments, we recognize that users with low levels of experience will be more likely to be involved in providing online support activities than those with high levels of experience. Hence, we propose that providing support to others will cause higher-level perceptions of well-being for users with low levels of experience.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The link between receiving online support and subjective well-being will be stronger for users with high levels of experience than that for users with low levels of experience.

As the density of social relationships increases through interactions over time, users will have a better understanding of each other and thus promote the development of shared values and shared identities [54]. At this stage, people will also make emotional investments in relationships among members and express genuine care and concern for the welfare of others [55,56]. A high social network density at this stage may enable people to appreciate others’ desires [55] and trigger more effective and value-adding resource exchanges among users [54]. Accordingly, users with high levels of experience may acquire more valuable resources and better emotional support from others than those with low levels of experience. Receiving more valuable resources and support may lead to higher levels of perception of well-being. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The link between providing online support and subjective well-being will be stronger for users with low levels of experience than that for users with high levels of experience.

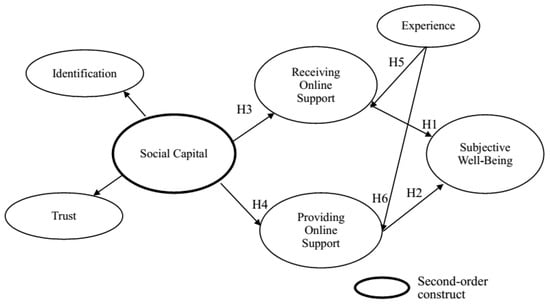

Based on the above arguments, we propose a research model, which is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model and hypotheses. H1: Receiving online support is positively related to subjective well-being. H2: Providing online support is positively related to subjective well-being. H3: Social capital is positively related to receiving online support. H4: Social capital is positively related to providing online support. H5: The link between receiving online support and subjective well-being will be stronger for users with high levels of experience than that for users with low levels of experience. H6: The link between providing online support and subjective well-being will be stronger for users with low levels of experience than that for users with high levels of experience.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Measurement Development

The measurement items were adapted from the previous literature or by converting the definition of items based on the relevant previous studies into a questionnaire format [57]. The questionnaire statistics are shown in Table 1. The items for measuring trust were adapted from [58] and [41], while identification was assessed by using the items adapted from [35] and [41]. The items measuring receiving online support and providing online support were developed on the basis of [1,14,23]. Finally, items for measuring subjective well-being were adapted from [59,60] and [7].

Table 1.

Demographic information about the respondents.

The contents of the questionnaire were validated by three experts in the field of IS who assessed the relevance and clarity of the questions. The items and structure of the instrument were solicited through comments and suggestions. We then developed the final measurement items for large-scale data collection. The items in the questionnaire were measured by using a five-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

3.2. Data Collection

The model was tested by using the data collected from users of various social media in Taiwan. To target social media users, a banner with a hyperlink connecting to the online survey was posted on a number of bulletin board systems (BBS), chat rooms, virtual communities, and Facebook. Members with social media use experience were invited to participate in our survey. A total of 267 questionnaires were collected for data analysis. The demographics of participants are shown in Table 1.

4. Data Analysis and Results

This study utilized the two-stage methodology recommended by [61] for data analysis. The first step assessed reliability and construct validity, while the second examined the structure model among the latent constructs. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was used as the structural equation modeling tool, because it imposes minimum restriction on measurement scale, sample size, and residual distribution [62] SmartPLS Version 2.0 M3 [63] was used in our data analysis.

4.1. Measurement Model

The adequacy of the measurement model was evaluated in terms of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Reliability was examined by using composite reliability (CR) values. As listed in Table 2, all CR values were greater than the commonly acceptable level of 0.70, indicating adequate composite reliability. Convergent validity of the scales was evaluated by using the two criteria suggested by [64]: (1) all indicator factor loadings should be significant and exceed 0.70, and (2) average variance extracted (AVE) by each construct should exceed the variance, due to measurement error for that construct (i.e., should exceed 0.50). As shown in Table 2, standardized CFA loadings for all items were significant and exceeded the minimum criterion of 0.7. Furthermore, as seen in Table 3, all AVE values of all constructs exceeded the minimum threshold value of 0.5. As such, the results demonstrate adequate convergent validity. Discriminant validity was evaluated by using the criteria recommended by [64]: the square root of the AVE should exceed the correlation shared between the construct and other constructs in the model. Table 3 lists the correlations among constructs, with the square root of the AVE on the diagonal. The results demonstrate acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Measurement items’ statistics.

Table 3.

Correlations and the square root of the AVE of latent variables.

In addition, Harman’s one-factor test was performed by entering all variables into a principal component analysis, to test for common method bias [65], since the data were collected by using self-reported measures. The results showed that the total variance of a single factor is 48.10%, below the cutoff threshold of 50.0% [65]. This result indicates that common method bias is not a major issue for this study. Furthermore, variance inflation factors (VIF) were used to assess the concerns of multicollinearity, because of the high correction between the constructs. We conducted a regression analysis by modeling subjective well-being as the dependent variable and the other four variables as the independent variables. The VIF ranged from 2.142 to 3.032, which is well below the threshold of 3.3 suggested by [66]. Therefore, the multicollinearity problem does not influence the result of this study.

4.2. Structural Model

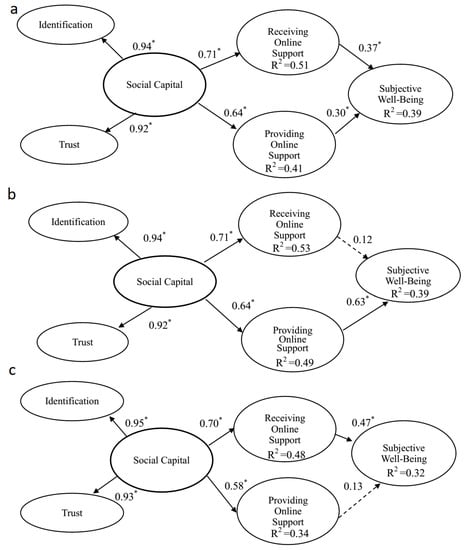

The theoretical model and hypothesized relationships were estimated by using the bootstrap approach, with a sample size of 500, to generate t-values and standard errors for determining the significance of paths in the structural model. Figure 2a summarizes the results of the structural model test. As hypothesized, receiving online support and providing online support exert positive impacts on subjective well-being (β = 0.37, 0.30; t = 4.56, 3.73, respectively). These results support H1 and H2. Furthermore, the results also indicate that social capital significantly impacts receiving and providing online support (β = 0.71, 0.64; t = 21.16, 16.06, respectively), supporting H3 and H4.

Figure 2.

SEM analysis of the research model. (a) results of full sample; (b) results of low-experience group; (c) results of high-experience group. * p < 0.1.

We used the subgroup analysis method to test the moderation effect of experience [67]. We first dichotomized use experience into two subgroups (high and low), using the mean splitting method, following [68]. We then estimated structural models for each subgroup and employed the formula implemented by [69], to test the moderating effects of experience, following [70] and [71]. Figure 2b,c and Table 4 summarize the results of the moderating-effect tests. The results show that the relationship between receiving online support and subjective well-being is stronger for users with high levels of experience, while providing online support has a stronger influence on subjective well-being for users with low levels of experience (t = 28.79, 40.39, respectively). Thus, H5 and H6 are supported.

Table 4.

Statistical comparison of paths for users with low- and high-use experience. * p < 0.1.

5. Discussion

5.1. Major Findings

This study integrated the perspectives of social capital, social support, and experience to investigate the factors affecting users’ subjective well-being on social media. The results reveal that receiving and providing online support are the two key factors affecting subjective well-being. The findings are similar to the standpoints of previous studies (e.g., [25,72]) in that people with more online social contacts are mentally happier and healthier than those with limited social contact. The findings also confirm the assertion of prior studies that fulfilling needs is a vital factor driving an individual’s well-being [25]. In line with the standpoint of previous studies (e.g., [10,14]), our results reveal that social capital has strong effects on receiving and providing online support, providing additional evidence that social capital is an important context factor that facilitates online social interactions.

The findings reveal that experience moderates the influences of receiving online support and providing online support on subjective well-being. Receiving online support predicts the subjective well-being for users in the low-experience subgroup, whereas providing online support has a positive effect on subjective well-being for users in the high-experience subgroup. The results are in line with the standpoint of the previous literature; high density of social relationship in a social unit helps users to receive more valuable help and emotional support [54,55]. The results also reveal that users with low levels of social relationship tend to provide support to facilitate social interactions with others, in order to strengthen their social network density. Furthermore, users’ perception of well-being increases when the different needs for users with different levels of experience can be fulfilled.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature examining the link between information-technology use and subjective well-being in three ways. First, we empirically tested the relationship between the influence of receiving online support and that of providing online support on subjective well-being. Although the previous literature argues that receiving support from others in a social unit increases an individual’s perception of well-being (e.g., [1]), few studies on social media have simultaneously investigated the effects of receiving and providing online support on subjective well-being. Therefore, this study contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence that receiving online support and providing online support are strong predictors of subjective well-being.

Second, while past studies have used the perspective of experience to examine the change of personal beliefs over time (e.g., [48,49]), few studies have been conducted to test whether the influences of online social-support activities (receiving and providing support) on subjective well-being vary as experience increases over time. This study contributes to the existing studies on well-being and social media by proving that receiving online support plays an important role in facilitating the perception of well-being for users with high levels of experience, while providing online support increases the perception of well-being for users with low levels of experience.

Finally, although online social support has been considered an important factor that determines individual behavior [1]. Little is known about the motivating factors for users’ social-support activities on social media. This study empirically tested the influence of social capital on online support activities and found that social capital fosters users’ online social-support activities. The results contribute to the existing literature on social media by revealing that social capital motivates members of a network on social media to provide and receive help from other members.

5.3. Practical Implications

In addition to the theoretical implications, this study provides valuable practical implications for managing social media. First, as the study demonstrates, social media has become an important medium that allows Internet users to build social relationships and to carry out social-support activities (receiving and providing support), which increases their perception of well-being. To increase social-support activities, from the viewpoint of the media synchronicity theory [19]. Managers of social media should improve their capabilities (e.g., transmission velocity, symbol variety, and parallelism) to provide better communication functionality. For example, social media could provide some emotional icons for users to easily provide emotional support to others. Social media may also provide additional mechanism for users to build their personal lists of social support networks. By using these lists, users can make a request about their needs and quickly respond to the needs of others.

Furthermore, our results reveal that building social capital effectively facilitates social-support activities. The previous literature suggests that self-disclosure behavior is a useful predictor of social capital [7]. In this regard, managers of social media may provide some mechanisms that allow users to build their personal profiles by using photos and videos [8]. In addition, privacy concerns have been considered a major barrier preventing users from engaging in social interactions on social media [73]. Thus, to increase social interactions on social media, managers of social media should deploy privacy protection mechanisms to protect users’ privacy information. Managers of social media may also provide user-information protection rules to enable users to have control of their personal information [74].

Finally, our results posit that providing online support significantly impacts subjective well-being for users with low levels of experience, while receiving online support positively influences subjective well-being for users with high levels of experience. To effectively strengthen users’ subjective well-being, managers of social media can deploy a mechanism to notify users with low levels of experience, in order to provide support for experienced users.

5.4. Limitations

While our study results reveal valuable findings, it is necessary to recognize its limitations. First, the proposed model was tested by using the data collected from social media users in Taiwan. Further studies should examine our findings in different countries, to test the generalizability of this study. Second, there are some factors, such as reciprocity (receiving and giving equal amounts of support) and mutual interdependence [16] that may affect social-support activities, which, in turn, affect users’ perceptions of well-being. Further studies should be conducted to explore the antecedents of subjective well-being by simultaneously integrating various standpoints (e.g., equity theory and social exchange theory). Future studies should also employ different aspects of social capital (e.g., structural capital and cognitive capital), to identify the antecedents of online support activities. Finally, while using experience to test the influences of different types of social-support activities on subjective well-being may advance our understanding about the change in users’ behaviors and beliefs as online social contacts increase over time, a longitudinal investigation is needed to examine how social networks develop over time and how users deal with stressful events by using social media [25]. Further studies should also investigate the effect of offline relationships on the link between social-support activities and subjective well-being, to examine whether offline relationships impact online support activities.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this study represents a systematic approach to understanding the antecedents of subjective well-being for social media users. Our results suggest that social capital enhances social-support activities. This study also extends our understanding about the moderating role of experience on the relationship between social support and subjective well-being. Social media providers should focus on the different effects of the two types of social-support activities on subjective well-being due to the differences in usage experience, to encourage users to stick to a specific social media.

Author Contributions

All authors have made significant contributions to this paper. M.-H.H. and C.-M.C. designed the framework. M.-H.H. and S.-L.W. collected data. C.-M.C. carried out data analysis. M.-H.H., C.-M.C. and S.-L.W. wrote the paper. C.-M.C. and S.-L.W. revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liang, T.P.; Ho, Y.T.; Li, Y.W.; Turban, E. What Drives Social Commerce: The Role of Social Support and Relationship Quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M.; Nevo, S.; Kock, N. Organizational members’ use of social networking sites and job performance: An exploratory study. Inf. Technol. People 2013, 26, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Li, E.Y.; Chang, W.L. Nurturing user creative performance in social media networks: An integration of habit of use with social capital and information exchange theories. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 869–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Hung, S.W. To give or to receive? Factors influencing members’ knowledge sharing and community promotion in professional virtual communities. Inf. Manag. 2010, 47, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.C. Online social network acceptance: A social perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hooff, B.; Huysman, M. Managing knowledge sharing: Emergent and engineering approaches. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.C.; Kuo, F.Y. Can Blogging Enhance Subjective Well-Being Through Self-disclosure? Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.M.; Hsu, M.H. Understanding the determinants of users’ subjective well-being in social networking sites: An integration of social capital theory and social presence theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Lee, P.S.N. Multiple determinants of life quality: The roles of Internet activities, use of new media, social support, and leisure activities. Telemat. Inform. 2005, 22, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Determinants of successful virtual communities: Contributions from system characteristics and social factors. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Richard, E.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, T.A.; Venkatesh, V.; Gosain, S. Model of acceptance with peer support: A social network perspective to understand employees’ system use. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Syme, S.L. (Eds.) Issues in the study and application of social support. In Social Support and Health; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani, I.; Bamberger, P.A.; Bacharach, S.B. Social support and employee well-being: The conditioning effect of perceived patterns of supportive exchange. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, I. Measures of self-perceived well-being. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.R.; Fuller, R.M.; Valacich, J.S. Media, tasks, and communication processes: A theory of media synchronicity. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, E.C. Positive and negative aspects of well-being: Common and specific predictors. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Theories in online information privacy research: A critical review and an integrated framework. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, C.M.; Gefen, D.; Arinze, B. Psychological barriers: Lurker and poster motivation and behavior in online communities. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2006, 18, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Gottlieb, B.H.; Underwood, L.G.; Cohen, S. Social relationships and health. In Social Support Measurement and Intervention; Cohen, S., Underwood, L., Gottlieb, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Eastin, M.S.; LaRose, R. Alt.support: Modeling social support online. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2005, 21, 977–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Brownell, A. Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.; Coyne, J.C.; Lazarus, R.S. The health-related functions of social support. J. Behav. Med. 1981, 4, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, D. An empirical study of the motivations for content contribution and community participation in Wikipedia. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Wu, Y.C.J. Gratifications and social network service usage: The mediating role of online experience. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Hadar, I.; Te’eni, D.; Unkelos-Shpigel, N.; Sherman, S.; Harel, N. Social networking in an academic conference context: Insights from a case study. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. In Knowledge and Social Capital; Lesser, E.L., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; Chapter 3; pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, C.Y.B.; Wei, K.K. Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimeister, J.M.; Schweizer, K.; Leimeister, S.; Krcmar, H. Do virtual communities matter for the social support of patients? Antecedents and effects of virtual relationships in online communities. Inf. Technol. People 2008, 21, 350–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J. Social capital on mobile SNS addiction A perspective from online and offline channel integrations. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.S.; Mobley, W.H. Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Fygenson, M. Understanding and predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.C.; Chiou, J.S. The effect of social capital on community loyalty in a virtual community: Test of a tripartite-process model. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, W.S.; Chan, L.S. Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational knowledge sharing. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Wang, T.G. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, K.; Chen, Y. Dynamical trust and reputation computation model for b2c e-commerce. Future Internet 2015, 7, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Paolucci, M.; Bagnoli, F.; Guazzini, A. Fairness and trust in virtual environments: The effects of reputation. Future Internet 2018, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 83, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-perception. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Volume 6, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.W.; Grube, A.; Meyers, J. Developing an optimal match within online communities: An exploration of CMC support communities and traditional support. J. Commun. 2001, 51, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold, H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier; MIT Press: Cambridge. MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Panteli, N.; Sockalingam, S. Trust and conflict within virtual inter-organizational alliances: A framework for facilitating knowledge sharing. Decis. Support Syst. 2005, 39, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Ju, T.L.; Yen, C.H.; Chang, C.M. Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D. Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, G.W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Behavioral intention formation knowledge sharing: Examining roles of extrinsic motivators, social–psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Chang, C.M.; Yen, C.H. Exploring the antecedents of trust in virtual communities. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social well-being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling, Modern Methods for Business Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta. Hamburg. 2005. Available online: http://www.smartpls.de (accessed on 29 September 2006).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.V.; Su, B.C.; Widjaja, A.E. Facebook C2C social commerce: A study of online impulse buying. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 83, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A cross- cultural study on escalation of commitment behavior in software projects. MIS Quarterly 2000, 24, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Franco, M.J.; Villarejo-Ramos, A.F.; Martin-Velicia, F.A. The moderating effect of gender on relationship quality and loyalty toward Internet service providers. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jin, X.L.; Fang, Y. Moderating role of gender in the relationships between perceived benefits and satisfaction in social virtual world continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 65, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, P.B.; Cao, J.; Everard, A. Privacy concerns versus desire for interpersonal awareness in driving the use of self-disclosure technologies: The case of instant messaging in two cultures. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 27, 163–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Teo, H.H.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Agarwal, R. Effects of individual self-protection, industry self-regulation, and government regulation on privacy concerns: A study of location-based services. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 1342–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).