Liraglutide and Exenatide in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Quality of Evidence

2.7. Reporting and Transparency

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

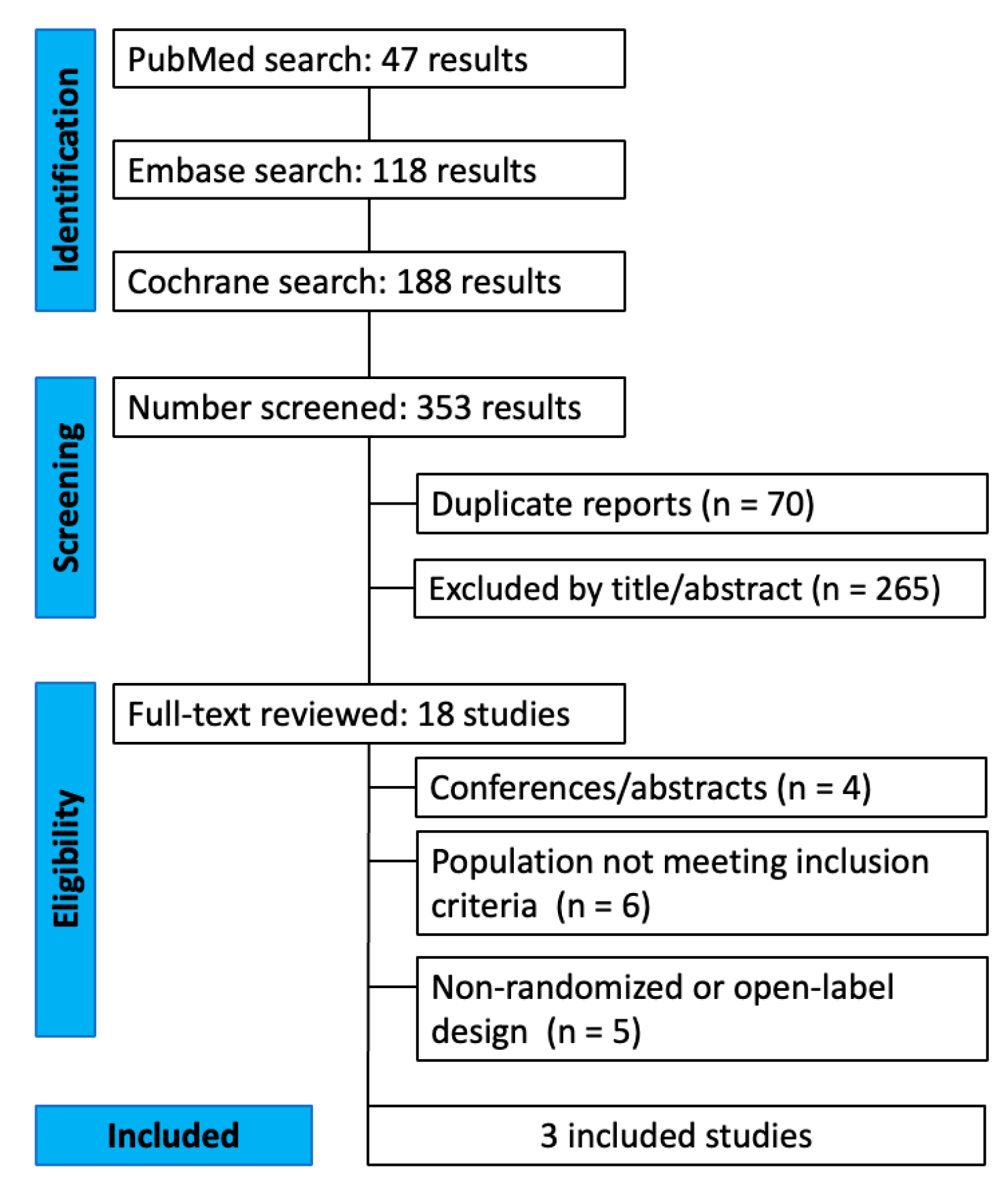

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

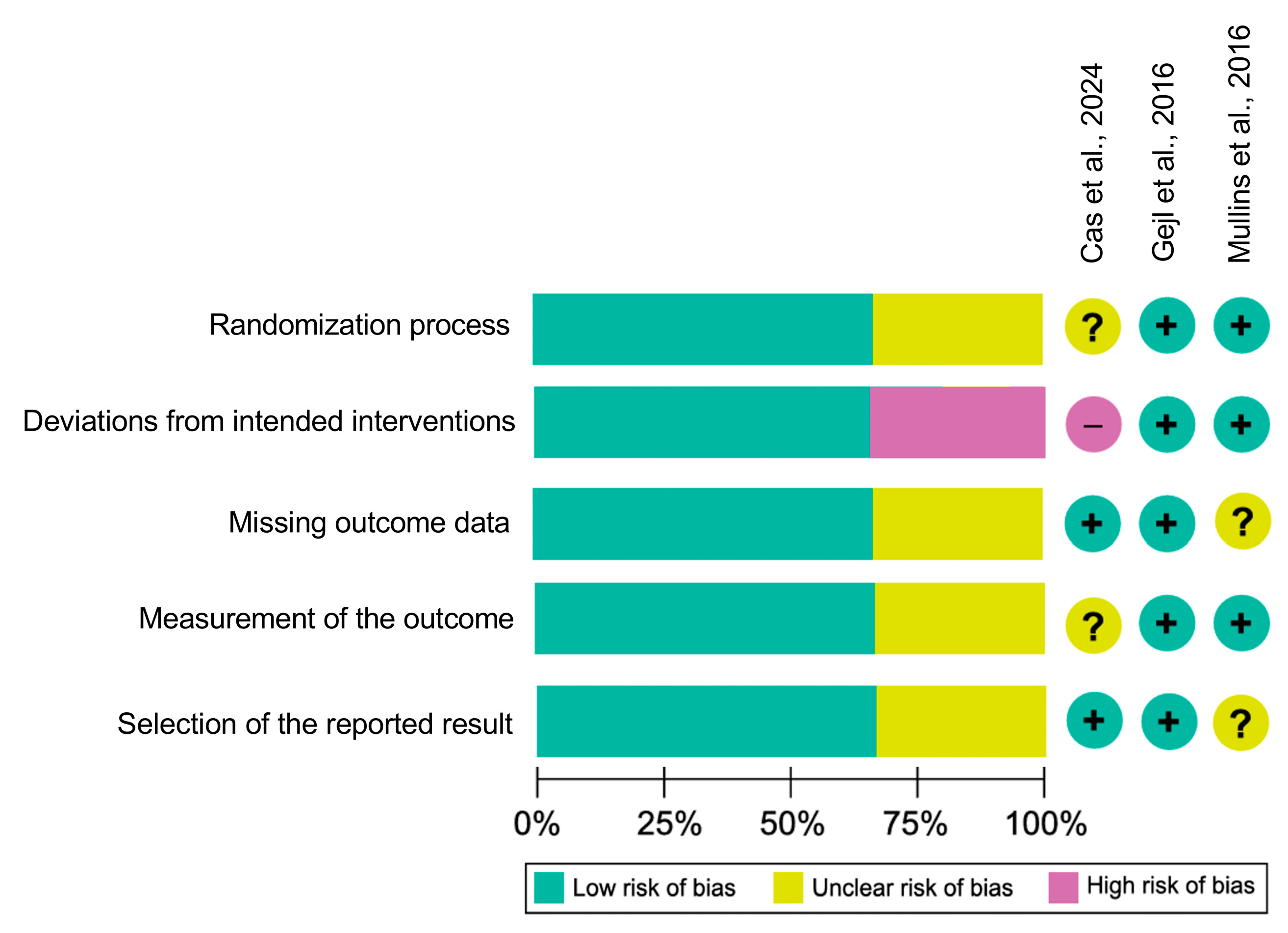

3.3. Risk of Bias

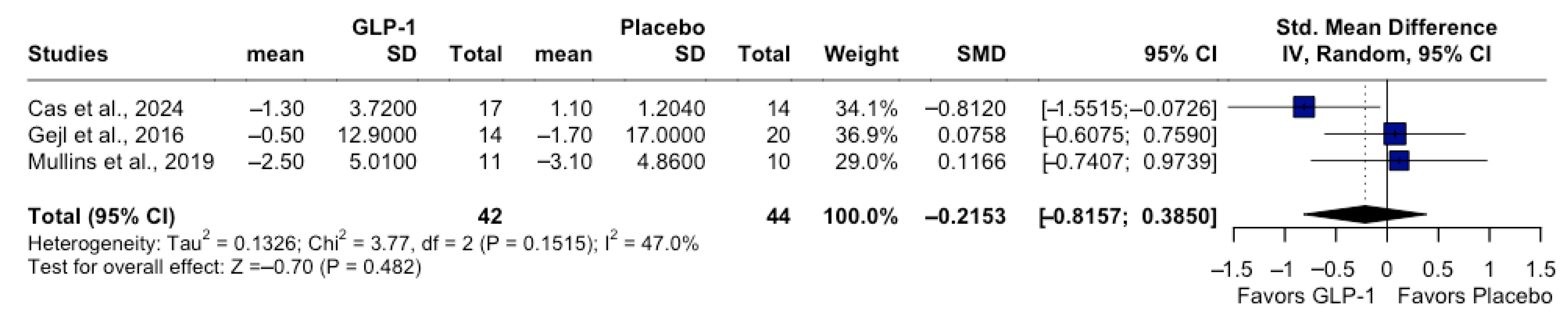

3.4. Quantitative Synthesis: Cognitive Outcomes

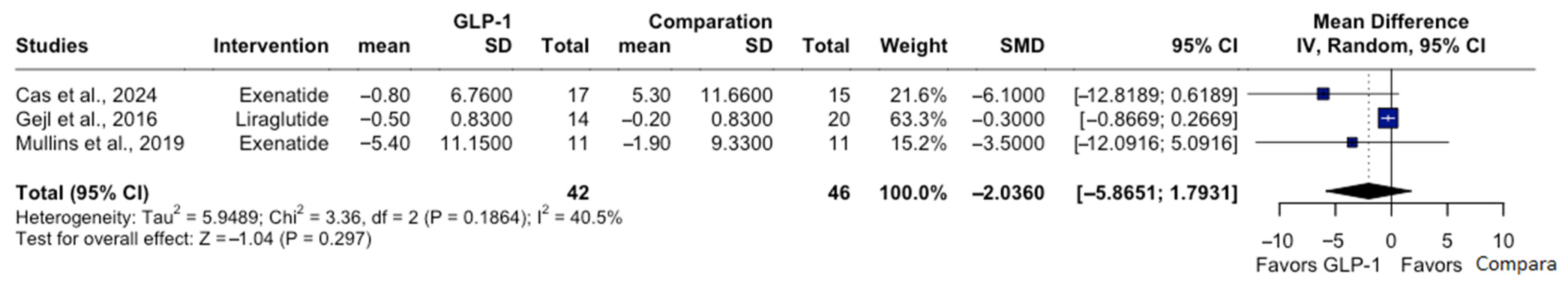

3.5. Secondary Outcomes: Fasting Plasma Glucose and Body Weight

3.6. Adherence and Adverse Events

3.7. Quality of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ADAS-Cog | Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive Subscale |

| Aβ | Amyloid-beta (quando aplicável ao texto científico) |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| FDG-PET | Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography |

| FPG | Fasting Plasma Glucose |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| RoB 2 | Risk of Bias 2 Tool |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| τ2 | Between-Study Variance (Tau-squared) |

References

- 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chetelat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L.; Burnham, S.; Bourgeat, P.; Brown, B.; Ellis, K.A.; Salvado, O.; Szoeke, C.; Macaulay, S.L.; Martins, R.; Maruff, P.; et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Monte, S.M. Brain insulin resistance and deficiency as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012, 9, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, N.; Holscher, C. The neuroprotective effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: An in-depth review. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 970925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, H.H.; Fabricius, K.; Barkholt, P.; Niehoff, M.L.; Morley, J.E.; Jelsing, J.; Pyke, C.; Knudsen, L.B.; Farr, S.A.; Vrang, N. The GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Liraglutide Improves Memory Function and Increases Hippocampal CA1 Neuronal Numbers in a Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 46, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClean, P.L.; Holscher, C. Liraglutide can reverse memory impairment, synaptic loss and reduce plaque load in aged APP/PS1 mice, a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes—State-of-the-art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atti, A.R.; Valente, S.; Iodice, A.; Caramella, I.; Ferrari, B.; Albert, U.; Mandelli, L.; De Ronchi, D. Metabolic Syndrome, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dei Cas, A.; Micheli, M.M.; Aldigeri, R.; Gardini, S.; Ferrari-Pellegrini, F.; Perini, M.; Messa, G.; Antonini, M.; Spigoni, V.; Cinquegrani, G.; et al. Long-acting exenatide does not prevent cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment: A proof-of-concept clinical trial. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejl, M.; Gjedde, A.; Egefjord, L.; Moller, A.; Hansen, S.B.; Vang, K.; Rodell, A.; Braendgaard, H.; Gottrup, H.; Schacht, A.; et al. In Alzheimer’s Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Mustapic, M.; Chia, C.W.; Carlson, O.; Gulyani, S.; Tran, J.; Li, Y.; Mattson, M.P.; Resnick, S.; Egan, J.M.; et al. A Pilot Study of Exenatide Actions in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L.; Atri, A.; Feldman, H.H.; Hansson, O.; Sano, M.; Knop, F.K.; Johannsen, P.; Leon, T.; Scheltens, P. evoke and evoke+: Design of two large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies evaluating efficacy, safety, and tolerability of semaglutide in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Li, T.; Deeks, J.J. Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 143–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schunemann, H.J.; Group, G.W. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V.; Flemyng, E. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024. Available online: www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cho, J.; Yoon, C.W.; Shin, J.H.; Seo, H.; Kim, W.R.; Na, H.K.; Byun, J.; Lockhart, S.N.; Kim, C.; Seong, J.K.; et al. Heterogeneity of factors associated with cognitive decline and cortical atrophy in early- versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mao, C.; Sun, A.; Yang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Fu, Z.; Babak, T.; Leverenz, J.B.; Pieper, A.A.; Luo, Y.; et al. Real-world observations of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors as potential treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminer, A.; Mulihano, A.; O’Brien, C.; Krewer, F.; Costello, M.; Judge, C.; O’Donnell, M.; Reddin, C. Cardioprotective Glucose-Lowering Agents and Dementia Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2025, 82, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Davis, P.B.; Qi, X.; Gurney, M.; Perry, G.; Volkow, N.D.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Associations of semaglutide with Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias in patients with type 2 diabetes: A real-world target trial emulation study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 106, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J. Comparative efficacy and safety of antidiabetic agents in Alzheimer’s disease: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.K.; Mukadam, N.; Kohl, G.; Livingston, G. Effect of diabetes medications on the risk of developing dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 104, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, C. Central effects of GLP-1: New opportunities for treatments of neurodegenerative diseases. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, T31–T41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaeus, C.S.; Nielsen, M.S.; Hogh, P. Microstates as Disease and Progression Markers in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Population | GLP-1 RAs | Duration | Dose | Follow-Up | Sample Size | Biomarker-Confirmed and Cognitive Assessments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dei Cas et al. [11] | Adults (50–80 years) with MCI, on stable medications ≥ 3 months | Exenatide | 8 months (32 weeks) | 2 mg/ week | 32 weeks | Exenatide n = 17; No treatment n = 15 | Clinical diagnosis (Petersen criteria); ADAS-Cog 11 |

| Mullins et al. [13] | Adults (>60 years), without diabetes, with amnestic MCI or mild AD | Exenatide | 18 months | 2 g/ week | 18 months | Exenatide n = 11; Placebo n = 10 | Clinical AD/MCI + CSF biomarkers (Aβ42, tau/p-tau); MMSE; ADAS-Cog 11 |

| Gejl et al. [12] | Adults (50–80 years) with AD (MMSE 18–21) | Liraglutide | 6 months (26 weeks) | 0.6–1.8 mg/day | 26 weeks | Liraglutide n = 14; Placebo n = 20 | Clinical AD + PET-based biomarker support (FDG-PET) WMS-IV |

| Study | n Random | n Completed (%) | Duration | Main Adverse Events | Discontinuations Due to AEs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gejl et al. [12] | 38 | 35 (92%) | 26 weeks | Nausea (3), Vomiting (1) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Mullins et al. [13] | 206 | 180 (87%) | 18 months | GI discomfort (8), Headache (3) | 6 (2.9%) |

| Dei Cas et al. [11] | 34 | 29 (85%) | 12 months | Nausea (2), Mild hypoglycemia (0) | 1 (3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Santos, P.; Sá Filho, A.S.; Aprigliano, V.; Duarte, A.G.; Ribeiro, N.A.; Lombardo, K.M.; Fajemiroye, J.O.; Buchholz, A.P.; Vaz, V.R.; Chiappa, G.R. Liraglutide and Exenatide in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Outcomes. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010069

Santos P, Sá Filho AS, Aprigliano V, Duarte AG, Ribeiro NA, Lombardo KM, Fajemiroye JO, Buchholz AP, Vaz VR, Chiappa GR. Liraglutide and Exenatide in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Outcomes. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Paula, Alberto Souza Sá Filho, Vicente Aprigliano, Amanda G. Duarte, Natã Alegransi Ribeiro, Katia Marques Lombardo, James Oluwagbamigbe Fajemiroye, Artur Prediger Buchholz, Victor Renault Vaz, and Gaspar R. Chiappa. 2026. "Liraglutide and Exenatide in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Outcomes" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010069

APA StyleSantos, P., Sá Filho, A. S., Aprigliano, V., Duarte, A. G., Ribeiro, N. A., Lombardo, K. M., Fajemiroye, J. O., Buchholz, A. P., Vaz, V. R., & Chiappa, G. R. (2026). Liraglutide and Exenatide in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Outcomes. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010069