Selection of Solubility Enhancement Technologies for S-892216, a Novel COVID-19 Drug Candidate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Samples

2.2.1. PEG 400 Solution

2.2.2. Amorphous Solid Dispersion Powder

2.2.3. Anhydrous Crystal Capsule

2.2.4. Amorphous Solid Dispersion Uncoated Tablet

2.2.5. Amorphous Solid Dispersion-Coated Tablet

2.3. Pharmacokinetics of S-892216 in Rats and Dogs

2.3.1. Animals

2.3.2. Rat Pharmacokinetic Study

2.3.3. Dog Pharmacokinetic Study

2.3.4. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

2.4. Evaluation of Degradation Products Level

2.5. Dissolution Testing

3. Results and Discussion

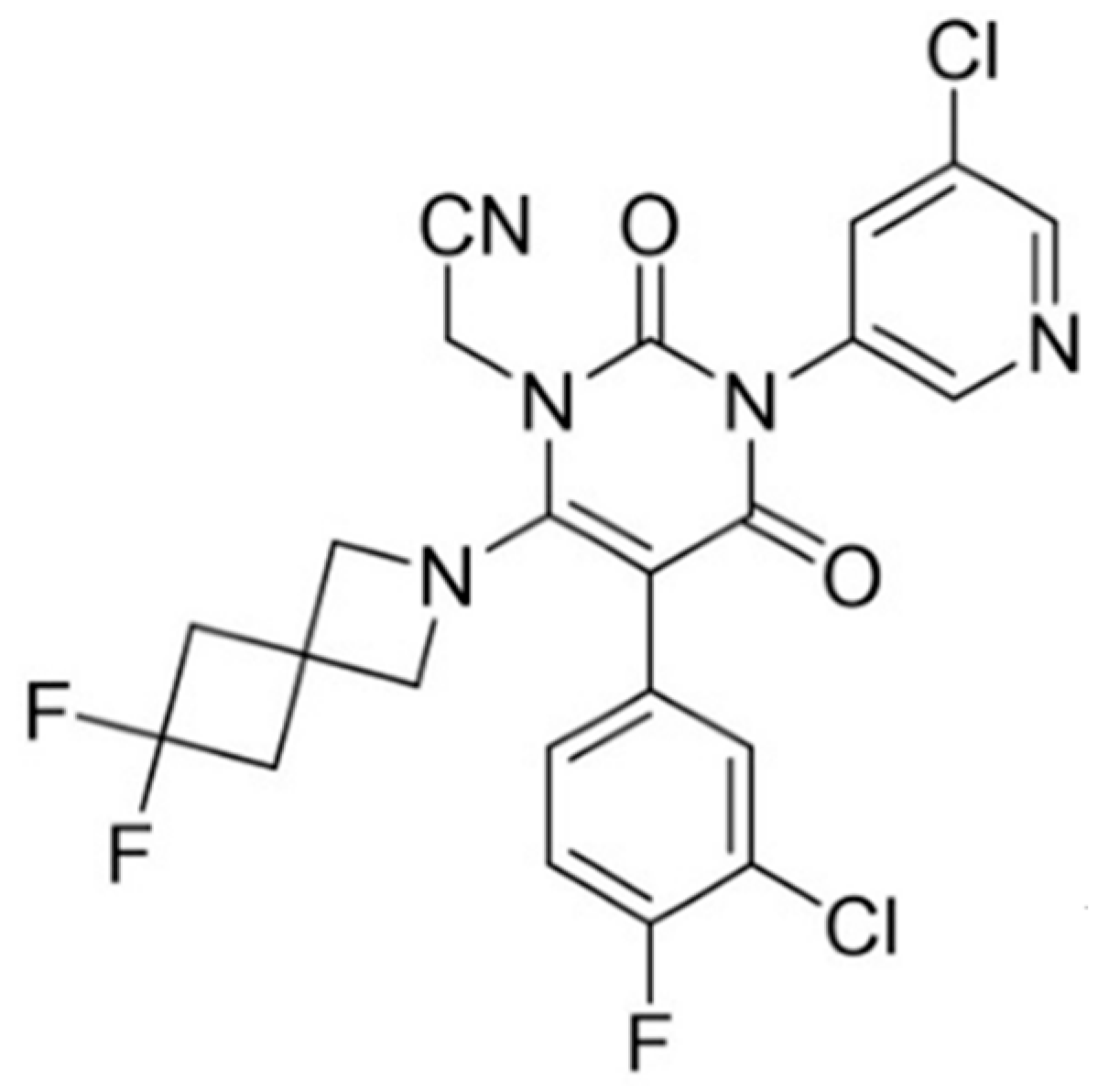

3.1. S-892216 Anhydrous Crystal

3.2. Formulation Development for Human ADME Studies

3.2.1. Oral Solution and Solid Dispersion Powder Development

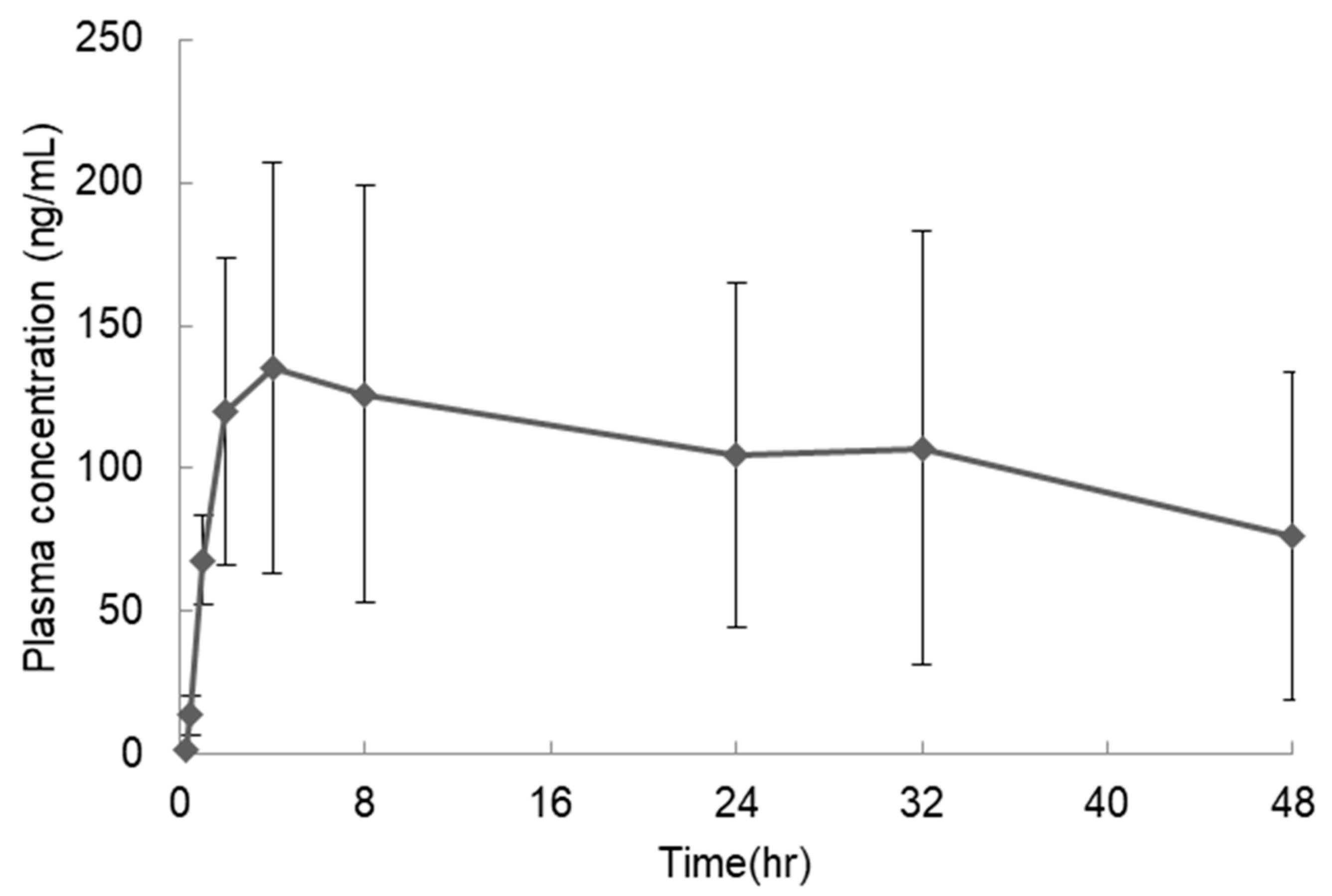

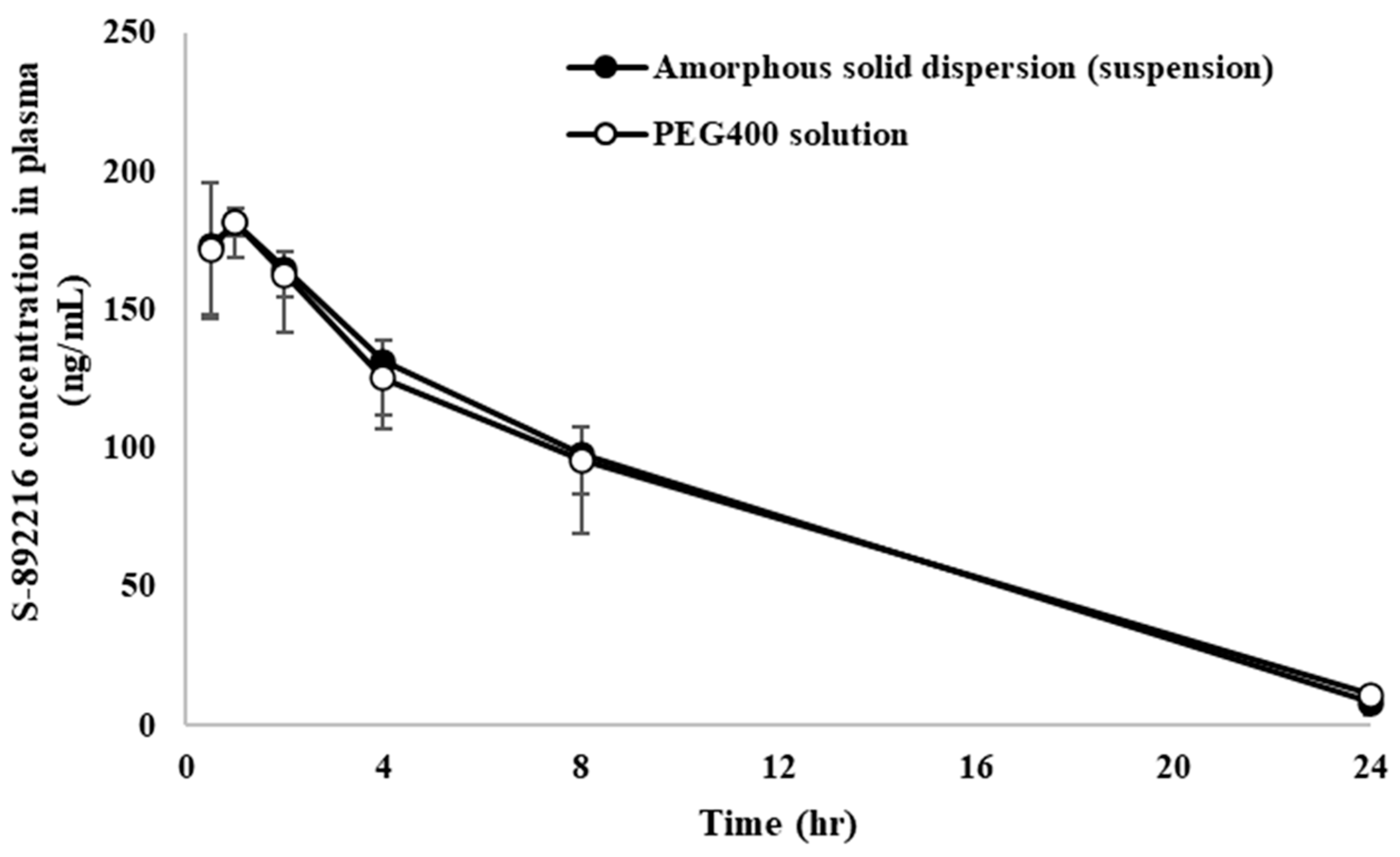

3.2.2. Evaluation of Pharmacokinetics

3.3. Development of To-Be-Marketed Formulation

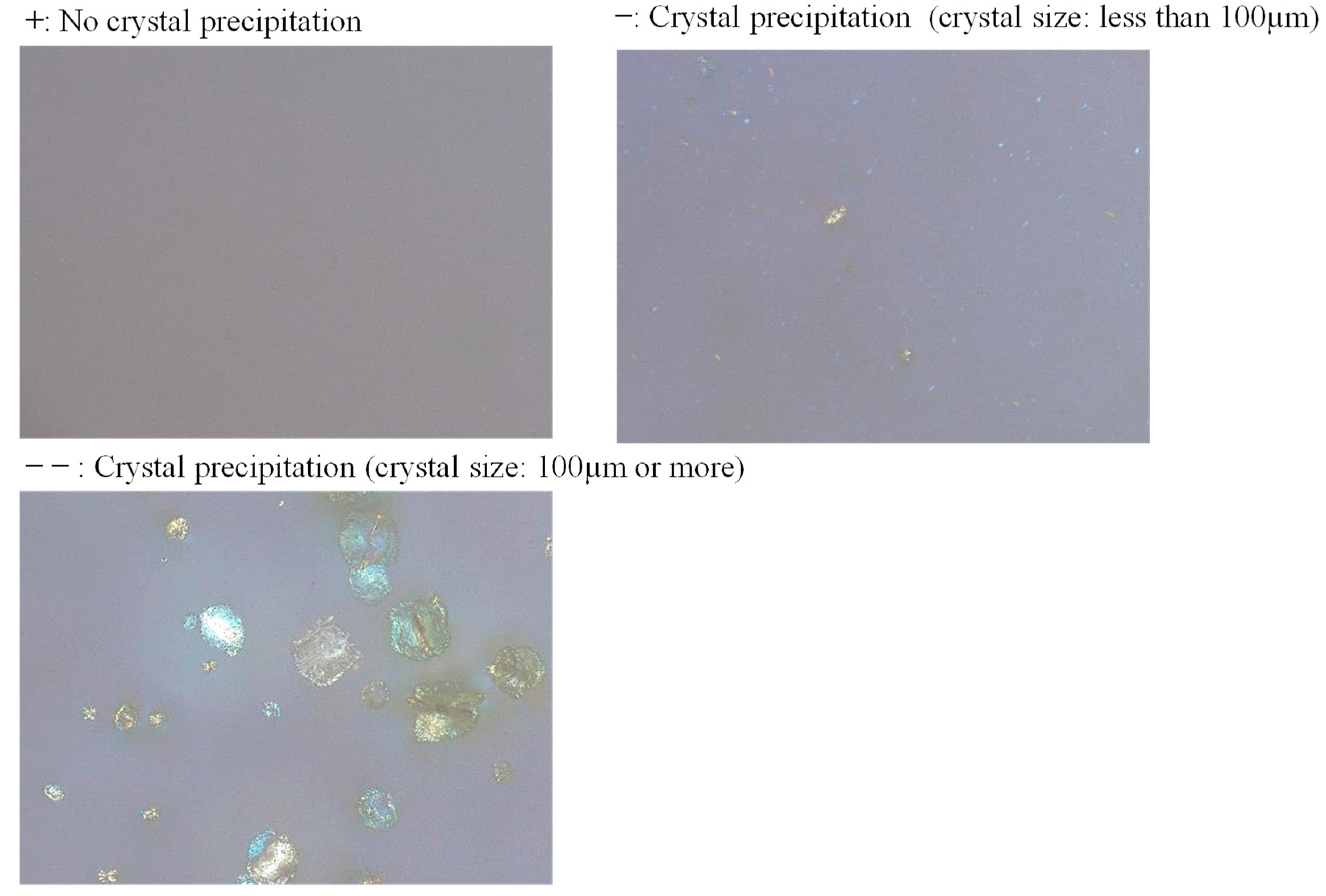

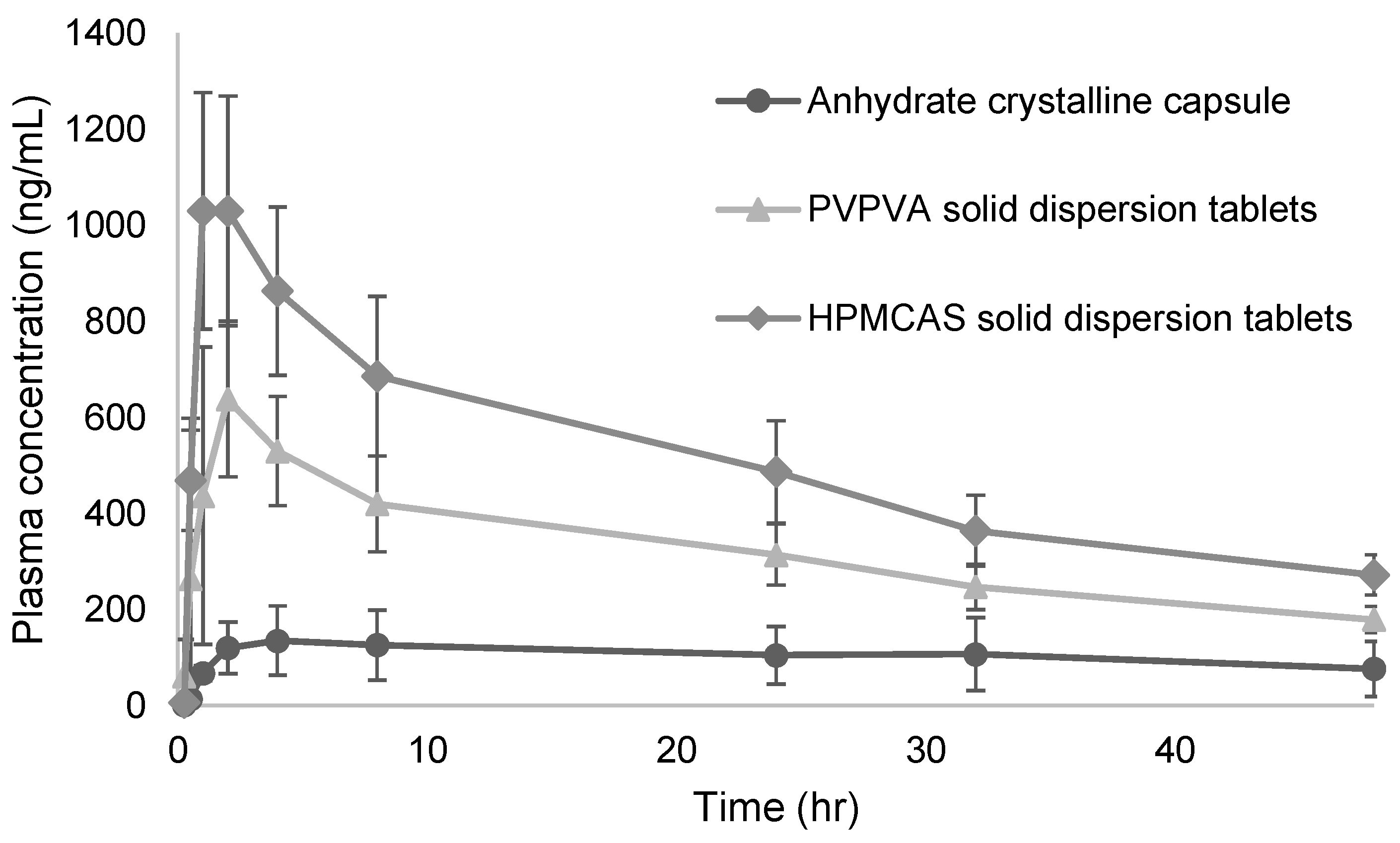

3.3.1. Polymer Selection for Solid Dispersion Tablet Development

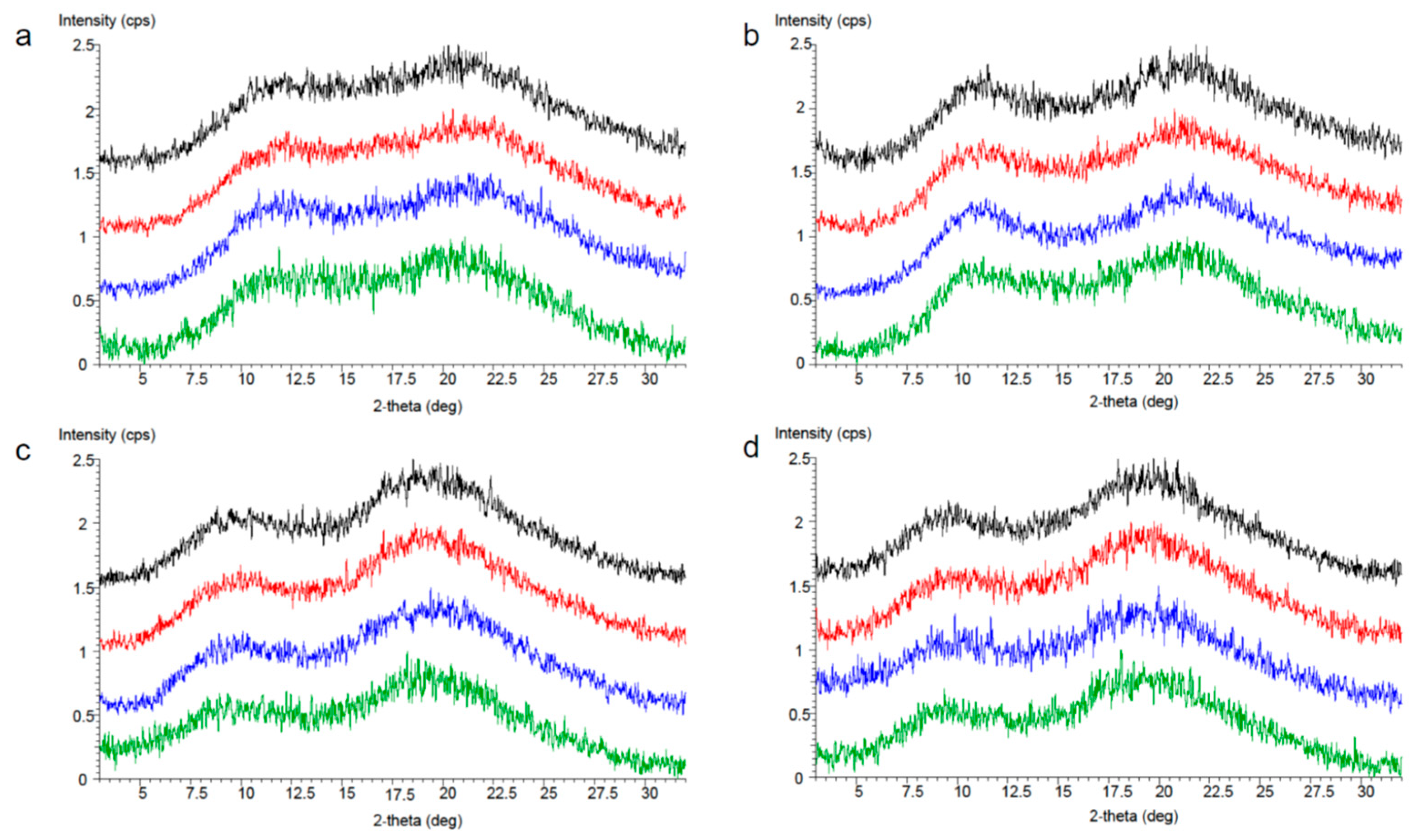

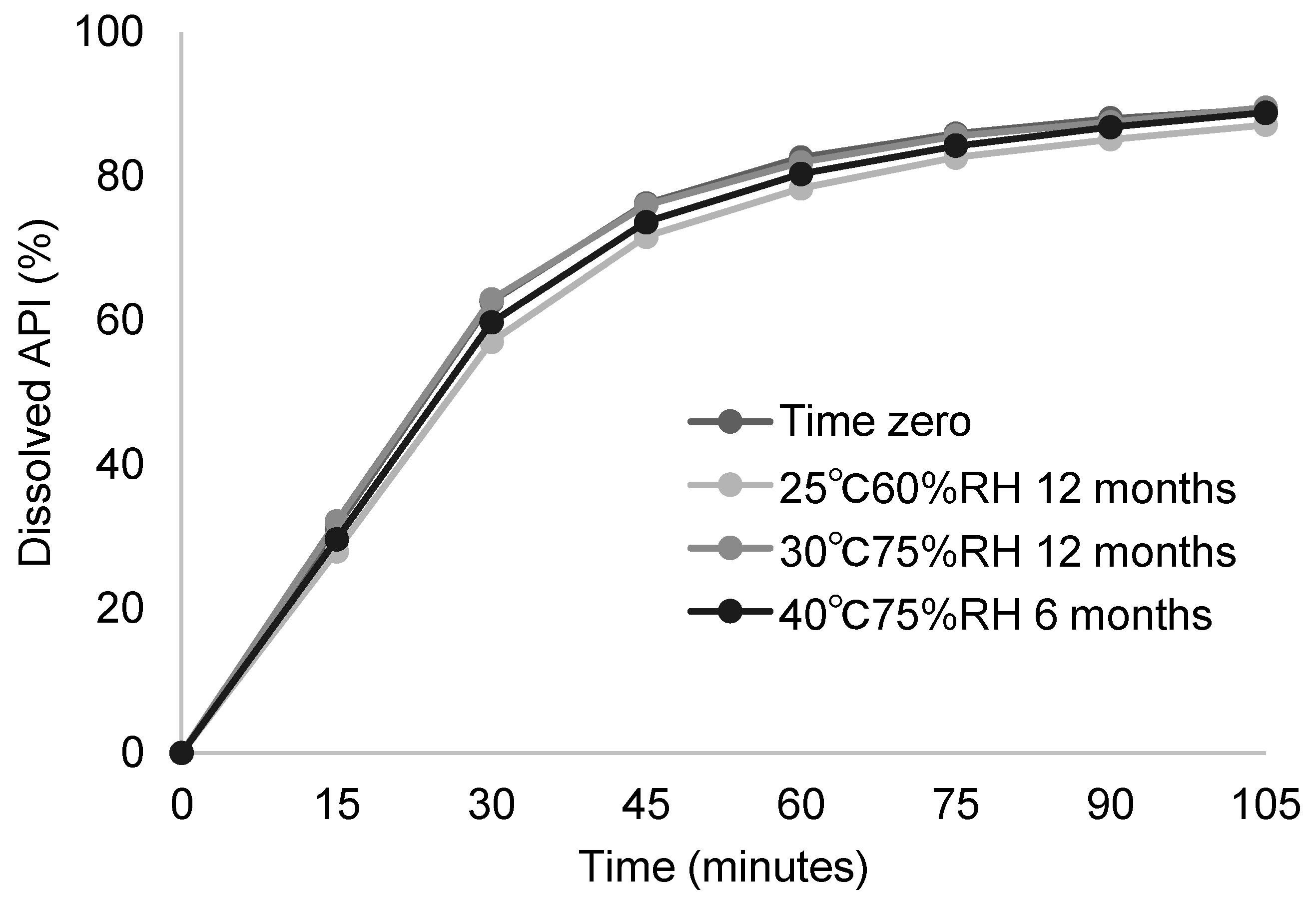

3.3.2. Stability Study of Developed Solid Dispersion Tablets

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| BA | Bioavailability |

| ADME | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray diffraction |

| PEG 400 | Polyethylene glycol 400 |

| PG | Propylene glycol |

| PVPVA | Polyvinylpyrrolidone-vinyl acetate |

| HPMCAS | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate |

| Cmax | Maximum plasma concentration |

| Tmax | Time to maximum plasma concentration |

| AUC | Area under the plasma concentration–time curve |

| SAD | Single ascending dose |

References

- World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO’s Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Unoh, Y.; Hirai, K.; Uehara, S.; Kawashima, S.; Nobori, H.; Sato, J.; Shibayama, H.; Hori, A.; Nakahara, K.; Kurahashi, K.; et al. Discovery of the Clinical Candidate S-892216: A Second-Generation of SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitor for Treating COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 5, 21099–21119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Aller, M.; Guillarme, D.; Veuthey, J.; Gurny, R. Strategies for formulating and delivering poorly water-soluble drugs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 30, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamba, I.; Sombié, C.B.; Yabré, M.; Zimé-Diawara, H.; Yaméogo, J.; Ouédraogo, S.; Lechanteur, A.; Semdé, R.; Evrard, B. Pharmaceutical approaches for enhancing solubility and oral bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 204, 114513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, Y.; Wada, K.; Nakatani, M.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: Basic approaches and practical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalepu, S.; Nekkanti, V. Insoluble drug delivery strategies: Review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, S.L.; Almarsson, O.; Peterson, M.L.; Remenar, J.F.; Read, M.J.; Lemmo, A.V.; Ellis, S.; Cima, M.J.; Gardner, C.R. High-throughput crystallization: Polymorphs, salts, co-crystals and solvates of pharmaceutical solids. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagden, N.; de Matas, M.; Gavan, P.T.; York, P. Crystal engineering of active pharmaceutical ingredients to improve solubility and dissolution rates. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, N.; Newman, A. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals and Their Physicochemical Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 2950–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuria, R.; Delori, A.; Jones, W.; Lipert, M.P.; Roy, L.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N. Pharmaceutical cocrystals and poorly soluble drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyano, T.; Ando, S.; Nagamatsu, D.; Watanabe, Y.; Sawada, D.; Ueda, H. Cocrystallization Enables Ensitrelvir to Overcome Anomalous Low Solubility Caused by Strong Intermolecular Interactions between Triazine-Triazole Groups in Stable Crystal Form. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 6473–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Z.H.; Samanta, A.K.; Heng, P.W.S. Overview of milling techniques for improving the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 10, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leane, M.; Pitt, K.; Reynolds, G.; Manufacturing Classification System (MCS) Working Group. A proposal for a drug product Manufacturing Classification System (MCS) for oral solid dosage forms. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2015, 20, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, T.; Sarmento, B.; Costa, P. Solid dispersions as strategy to improve oral bioavailability of poor water soluble drugs. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghel, S.; Cathcart, H.; O’Reilly, N.J. Polymeric Amorphous Solid Dispersions: A Review of Amorphization, Crystallization, Stabilization, Solid-State Characterization, and Aqueous Solubilization of Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II Drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.S.; Zhang, G.G.Z. Physical chemistry of supersaturated solutions and implications for oral absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 101, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermain, S.V.; Brough, C.; Williams, R.O., 3rd. Amorphous solid dispersions and nanocrystal technologies for poorly water-soluble drug delivery—An update. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Lipid formulations for oral administration of drugs: Non-emulsifying, self-emulsifying and ‘self-microemulsifying’ drug delivery systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 11, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Formulation of poorly water-soluble drugs for oral administration: Physicochemical and physiological issues and the lipid formulation classification system. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 29, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Kuentz, M.; Ilie-Spiridon, A.R.; Griffin, B.T. Lipid based formulations as supersaturating oral delivery systems: From current to future industrial applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 189, 106556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spracklin, D.K.; Chen, D.; Bergman, A.J.; Callegari, E.; Obach, R.S. Mini-Review: Comprehensive Drug Disposition Knowledge Generated in the Modern Human Radiolabeled ADME Study. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2020, 9, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.C.; Spracklin, D.K.; James, A.D.; Hvenegaard, M.G.; Scarfe, G.; Wagner, D.S.; Georgi, K.; Schieferstein, H.; Bjornsdottir, I.; van Groen, B.; et al. Considerations for Human ADME Strategy and Design Paradigm Shift(s)—An Industry White Paper. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 113, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Yang, Z.; Tatavarti, A.; Xu, W.; Fuerst, J.; Ormes, J. Designing an ADME liquid formulation with matching exposures to an amorphous dosage form. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 554, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J. Formulation Development Strategy for Early Phase Human Studies. Available online: https://drug-dev.com/formulation-forum-formulation-development-strategy-for-early-phase-human-studies (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Lyon, R.C.; Taylor, J.S.; Porter, D.A.; Prasanna, H.R.; Hussain, A.S. Stability profiles of drug products extended beyond labeled expiration dates. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilker, M.; Sörgel, F.; Holzgrabe, U. A systematic review of the stability of finished pharmaceutical products and drug substances beyond their labeled expiry dates. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamblin, S.L.; Hancock, B.C.; Pikal, M.J. Coupling between chemical reactivity and structural relaxation in pharmaceutical glasses. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 2254–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, C.; Pikal, M.J. Role of thermodynamic, molecular, and kinetic factors in crystallization from the amorphous state. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 1329–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioglu-Tuncil, S.; Voelker, A.L.; Taylor, L.S.; Mauer, L.J. Amorphization of Thiamine Chloride Hydrochloride: Effects of Physical State and Polymer Type on the Chemical Stability of Thiamine in Solid Dispersions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Li, F.; Yeh, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, J. Physical stability of amorphous pharmaceutical solids: Nucleation, crystal growth, phase separation and effects of the polymers. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 590, 119925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosle, M.; Benner, J.S.; Dekoven, M.; Shelton, J. Difficult to swallow: Patient preferences for alternative valproate pharmaceutical formulations. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2009, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.T.L.; Steadman, K.J.; Cichero, J.A.Y.; Nissen, L.M. Dosage form modification and oral drug delivery in older people. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 135, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummler, H.; Page, S.; Stillhart, C.; Meilicke, L.; Grimm, M.; Mannaa, M.; Gollasch, M.; Weitschies, W. Influence of Solid Oral Dosage Form Characteristics on Swallowability, Visual Perception, and Handling in Older Adults. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nespi, M.; Kuhn, R.; Yen, C.W.; Lubach, J.W.; Leung, D. Optimization of Spray-Drying Parameters for Formulation Development at Preclinical Scale. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhujbal, S.V.; Mitra, B.; Jain, U.; Gong, Y.; Agrawal, A.; Karki, S.; Taylor, L.S.; Kumar, S.; Zhou, Q.T. Pharmaceutical amorphous solid dispersion: A review of manufacturing strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2505–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.F.; Tong, W.Q. Impact of solid state properties on developability assessment of drug candidates. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomeir, A.A.; Morrison, R.; Prelusky, D.; Korfmacher, W.; Broske, L.; Hesk, D.; McNamara, P.; Mei, H. Estimation of the extent of oral absorption in animals from oral and intravenous pharmacokinetic data in drug discovery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 4027–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Swift, B.; Mamelok, R.; Pine, S.; Sinclair, J.; Attar, M. Design and Conduct Considerations for First-in-Human Trials. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2019, 12, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Strategies to Identify and Mitigate Risks for First-in-Human and Early Clinical Trials with Investigational Medicinal Products. 2017. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-strategies-identify-and-mitigate-risks-first-human-and-early-clinical-trials-investigational-medicinal-products-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, P.; Zhao, L. Developing early formulations: Practice and perspective. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 341, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmaceutical Manufacturer. The Drug Formulation Steps to Take During First-in-Human (FIH) Trials. 2018. Available online: https://pharmaceuticalmanufacturer.media/pharmaceutical-industry-insights/how-to-succeed-in (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Strickley, R.G. Solubilizing excipients in oral and injectable formulations. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, P.; Bulusu, R.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W.; Singh, M. Amorphous solid dispersions: An update for preparation, characterization, mechanism on bioavailability, stability, regulatory considerations and marketed products. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Van den Mooter, G. Spray drying formulation of amorphous solid dispersions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 100, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.; Vemula, S.K.; Narala, S.; Lakkala, P.; Munnangi, S.R.; Narala, N.; Jara, M.O.; Williams, R.O., 3rd; Terefe, H.; Repka, M.A. Hot-Melt Extrusion: From Theory to Application in Pharmaceutical Formulation-Where Are We Now? AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Obara, S.; Liu, F.; Fu, W.; Zhang, W.; Kikuchi, S. Melt Extrusion for a High Melting Point Compound with Improved Solubility and Sustained Release. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, P.; Andersson, A.; Cole, S. The Importance of the Human Mass Balance Study in Regulatory Submissions. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2019, 8, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappin, G.; Kuhnz, W.; Jochemsen, R.; Kneer, J.; Chaudhary, A.; Oosterhuis, B.; Drijfhout, W.J.; Rowland, M.; Garner, R.C. Use of microdosing to predict pharmacokinetics at the therapeutic dose: Experience with 5 drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 80, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappin, G.; Noveck, R.; Burt, T. Microdosing and drug development: Past, present and future. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013, 9, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DailyMed Database. PAXLOVID- Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir Kit. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=8a99d6d6-fd9e-45bb-b1bf-48c7f761232a (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- DailyMed Database. LAGEVRIO- Molnupiravir Capsule. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=05727725-6bd1-48de-a65a-662882b07a2d (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Syed, Y.Y. Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry, Size, Shape, and Other Physical Attributes of Generic Tablets and Capsules. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/161902/download (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Limenh, L.W.; Tessema, T.A.; Simegn, W.; Ayenew, W.; Bayleyegn, Z.W.; Sendekie, A.K.; Chanie, G.S.; Fenta, E.T.; Beyna, A.T.; Kasahun, A.E. Patients’ Preference for Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms: Does It Affect Medication Adherence? A Cross-Sectional Study in Community Pharmacies. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DailyMed Database. NEORAL- Cyclosporine Capsule, Liquid-Filled NEORAL- Cyclosporine Solution. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=94461af3-11f1-4670-95d4-2965b9538ae3 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Hemenway, J.N.; Carvalho, T.C.; Rao, V.M.; Wu, Y.; Levons, J.K.; Narang, A.S.; Paruchuri, S.R.; Stamato, H.J.; Varia, S.A. Formation of reactive impurities in aqueous and neat polyethylene glycol 400 and effects of antioxidants and oxidation inducers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3305–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrózka-Cieślik, A.; Dolińska, B.; Ryszka, F. Influence of the selected antioxidants on the stability of the Celsior solution used for perfusion and organ preservation purposes. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantratid, E.; Dressman, J.B. Biorelevant Dissolution Media Simulating the Proximal Human Gastrointestinal Tract: An Update. Dissolut. Technol. 2009, 16, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, W.; Thoma, K. The influence of formulation and manufacturing process on the photostability of tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 243, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawi, A. Pharmaceutical Coating and Its Different Approaches, a Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechard, S.R.; Quraishi, O.; Kwong, E. Film coating: Effect of titanium dioxide concentration and film thickness on the photostability of nifedipine. Int. J. Pharm. 1992, 87, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF); Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Engel, K.H.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Gürtler, R.; et al. Safety assessment of titanium dioxide (E171) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Composition (mg) | Composition (%w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| S-892216 drug substance | 0.30 | 0.14 |

| PVPVA | 3.26 | 1.51 |

| Ascorbic acid | 1.25 | 0.58 |

| PEG 400 | 110.9 | 51.53 |

| Propylene glycol | 99.5 | 46.24 |

| Total | 215.2 | 100.0 |

| Component | Composition (mg) |

|---|---|

| S-892216 drug substance | 30.0 |

| Mannitol | 54.8 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 54.8 |

| Croscarmellose sodium | 7.5 |

| Magnesium stearate | 3.0 |

| Total (mg) | 150.0 |

| Hypromellose capsule | 1 unit |

| Component | Composition (mg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Formulation | PVPVA solid dispersion tablet | HPMCAS solid dispersion tablet |

| S-892216-PVPVA Solid dispersion (as S-892216) | 120.0 (30.0) | - |

| S-892216-HMPCAS-LF Solid dispersion (as S-892216) | - | 120.0 (30.0) |

| Mannitol | 72.0 | 72.0 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 72.0 | 72.0 |

| Croscarmellose sodium | 30.0 | 30.0 |

| Magnesium stearate | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Total (mg) | 300.0 | 300.0 |

| Solvent 1 | Solubility (µg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Purified water | 0.71 |

| JP-1 fluid (pH 1.2) | 1.08 |

| McIlvaine buffer (pH 4.0) | 0.64 |

| JP-2 fluid (pH 6.8) | 0.61 |

| Dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (ng/mL) | Tmax (h) | AUCinf (ng·h/mL) | BA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 152 ± 71 | 12.7 ± 16.8 | 6500 ± 4120 1 | 22.2 ± 14.1 |

| Storage Period | Solvent (Acetone: Ethanol) | Time Zero | 40 °C75%RH 1 Week | 60 °C 1 Week | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Concentration in Solid Dispersion (% w/w) | 10 | 25 | 50 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Polymer | PVPVA | 100:0 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| PVP | 80:20 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| HPMC AS-MF | 20:1 | − | − | −− | − | − | −− | − | − | −− | |

| HPMC AS-LF | 20:1 | − | − | −− | − | −− | −− | − | −− | −− | |

| HPMCP | 8:2 | − | −− | −− | − | −− | −− | − | −− | −− | |

| HPC SL | 8:2 | − | −− | −− | −− | −− | −− | −− | −− | −− | |

| EUDRAGIT L100 | 1:1 | + | − | − | + | −− | −− | + | −− | −− | |

| Formulation | Dose | Feeding | Cmax | Tmax | AUCinf | BA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/mL) | (h) | (ng·h/mL) | (%) | |||

| PEG 400 solution | 1 mg/kg | Fasted | 186 ± 12 | 0.833 ± 0.289 | 1972 ± 157 | 101 ± 8 |

| PVPVA solid dispersion suspension | Fasted | 182 ± 13 | 0.83 ± 0.29 | 1970 ± 480 | 110 ± 27 |

| Formulation | Cmax | Tmax | AUCinf | BA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/mL) | (h) | (ng·h/mL) | (%) | |

| Anhydrous crystal capsules | 152 ± 71 | 12.7 ± 16.8 | 6500 ± 4120 | 22.2 ± 14.1 |

| HPMCAS solid dispersion tablets | 1040 ± 241 | 1.67 ± 0.58 | 36,200 ± 5300 | 123.6 ± 18.0 |

| PVPVA solid dispersion tablets | 697 ± 177 | 1.67 ± 0.58 | 23,200 ± 3300 | 79.2 ± 11.1 |

| Storage Period | Amount of Degradation Product (Individual Max) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Week | 2 Weeks | |

| PVPVA solid dispersion tablet | 0.08% | 0.11% |

| HPMCAS solid dispersion tablet | 0.32% | 0.44% |

| Component | Composition (mg) |

|---|---|

| S-892216 PVPVA Solid dispersion (as S-892216) | 160.0 (40.0) |

| Mannitol | 148.8 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 37.2 |

| Croscarmellose sodium | 40.0 |

| Colloidal silicon dioxide | 2.0 |

| Sodium stearyl fumarate | 12.0 |

| Subtotal | 400.0 |

| Coating agent (Hypromellose) (Talc) (Red Ferric Oxide) (Yellow Ferric Oxide) | 16.0 (70.330% w/w) (28.966% w/w) (0.352% w/w) (0.352% w/w) |

| Total | 416.0 |

| Storage Condition and Period | Amount of Degradation Product (%, Individual Max) | Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degradation Product A | Degradation Product B | Others | ||

| Time zero | <0.10 | 0.01 | <0.10 | 0.01 |

| 25 °C/60%RH 12 months in blister packaging | <0.10 | 0.06 | <0.10 | 0.06 |

| 30 °C/75%RH 12 months in blister packaging | <0.10 | 0.12 | <0.10 | 0.12 |

| 40 °C/75%RH 6 months in blister packaging | <0.10 | 0.28 | <0.10 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohashi, R.; Otake, S.; Murata, T.; Watari, R.; Yoshida, S.; Kitade, M.; Kondo, D.; Kimura, G. Selection of Solubility Enhancement Technologies for S-892216, a Novel COVID-19 Drug Candidate. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121627

Ohashi R, Otake S, Murata T, Watari R, Yoshida S, Kitade M, Kondo D, Kimura G. Selection of Solubility Enhancement Technologies for S-892216, a Novel COVID-19 Drug Candidate. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121627

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhashi, Ryo, Shuichi Otake, Tatsuhiko Murata, Ryosuke Watari, Shinpei Yoshida, Mikiko Kitade, Daisuke Kondo, and Go Kimura. 2025. "Selection of Solubility Enhancement Technologies for S-892216, a Novel COVID-19 Drug Candidate" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121627

APA StyleOhashi, R., Otake, S., Murata, T., Watari, R., Yoshida, S., Kitade, M., Kondo, D., & Kimura, G. (2025). Selection of Solubility Enhancement Technologies for S-892216, a Novel COVID-19 Drug Candidate. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121627