Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatments on Melasma Area Severity Index and Quality of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Quality Assessment

2.2. Sample Origin

2.3. Sample Characterization

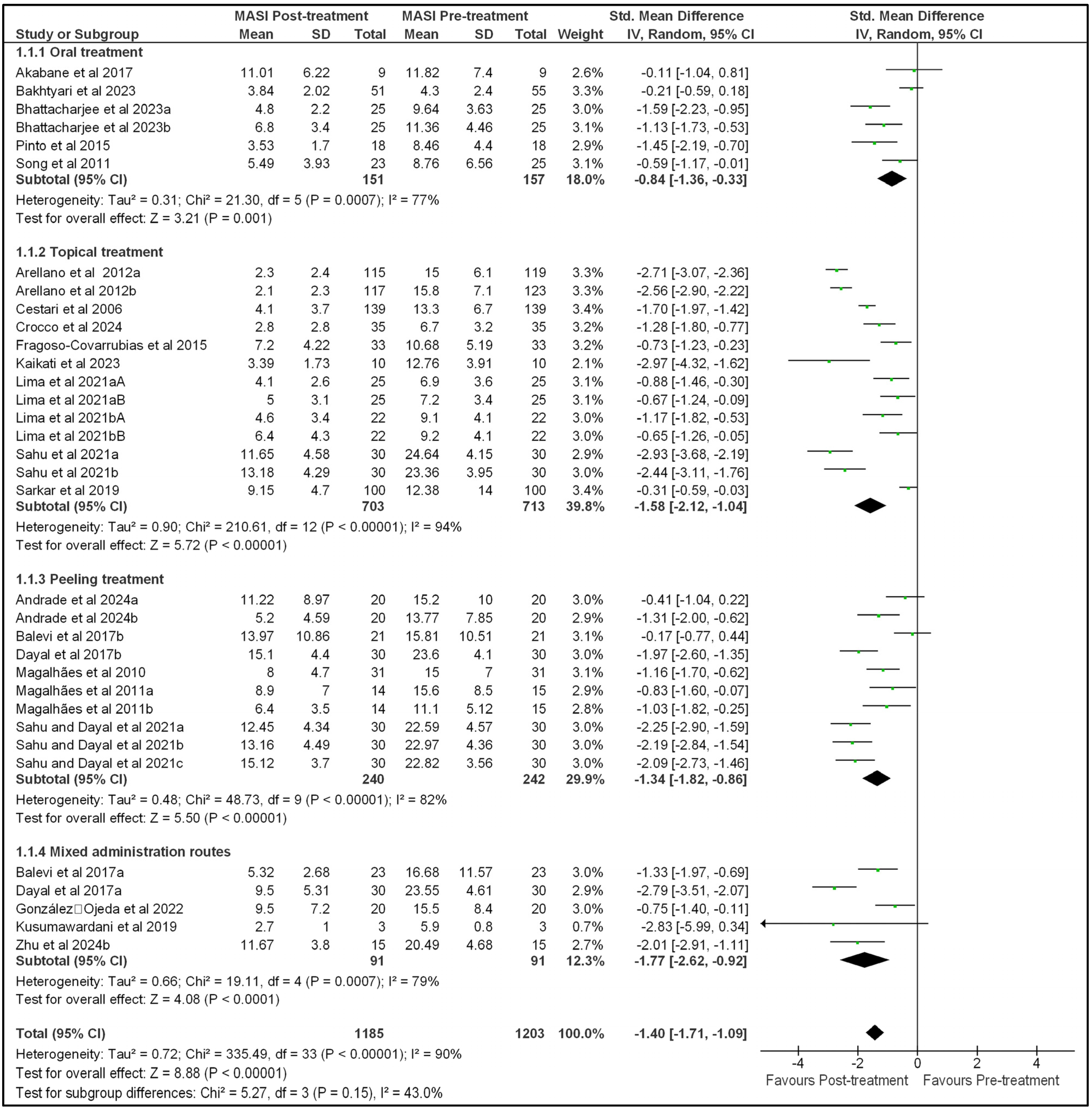

2.4. Effect of Treatment on MASI and MELASQoL

2.5. MASI and MELASQoL Relationship

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Systematic Review

4.1.1. Search Strategy

4.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

4.1.3. Data Extraction

4.2. Quality Assessment

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Handel, A.C.; Miot, L.D.; Miot, H.A. Melasma: A clinical and epidemiological review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.; Schiechert, R.A.; Zaiac, M.N. Melasma Associated with Topical Estrogen Cream. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2017, 10, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.H.; Na, J.I.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, K.C. Melasma: Updates and perspectives. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, G.M.; Borges, M.; Oliveira, P.J.V.; Neves, D.R. Lactic acid chemical peel in the treatment of melasma: Clinical evaluation and impact on quality of life. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2010, 2, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kagha, K.; Fabi, S.; Goldman, M.P. Melasma’s Impact on Quality of Life. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, A.; Pereira, M.; Moisés, T.; Cordero, T.; Silva, A.R.; Amazonas, F.T.P.; Bentivoglio, F.; Pereira, E.S.P. Evaluation of quality of life improvement in melasma patients, measured by the MELASQoL following the use of a botanical combination based on Bellis perennis, Glycyrrhiza glabra e Phyllanthus emblica. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2011, 3, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Jusuf, N.K.; Putra, I.B.; Mahdalena, M. Is There a Correlation between Severity of Melasma and Quality of Life? Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 2615–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.C.C.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Jorge, M.F.S.; D’Elia, M.P.B.; Miot, H.A. Depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in women with facial melasma: An Internet-based survey in Brazil. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, e346–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough-Green, C.K.; Griffiths, C.E.; Finkel, L.J.; Hamilton, T.A.; Bulengo-Ransby, S.M.; Ellis, C.N.; Voorhees, J.J. Topical retinoic acid (tretinoin) for melasma in black patients. A vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch. Dermatol. 1994, 130, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, J.; Oliveira, T.G.; Curi, V.C.; Macedo, A.C.L.; Sakai, F.D.P.; Vasconcelos, R.C.F. Application of lactic acid peeling in patients with melasma: A comparative study. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2014, 6, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Balkrishnan, R.; McMichael, A.J.; Camacho, F.T.; Saltzberg, F.; Housman, T.S.; Grummer, S.; Feldman, S.R.; Chren, M.-M. Development and validation of a health-related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cestari, T.F.; Hexsel, D.; Viegas, M.L.; Azulay, L.; Hassun, K.; Almeida, A.R.; Rêgo, V.R.P.A.; Mendes, A.M.D.; Filho, J.W.A.; Junqueira, H. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for Brazilian Portuguese language: The MelasQoL-BP study and improvement of QoL of melasma patients after triple combination therapy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 156, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, A.R.; Balkrishnan, R.; Ellzey, A.R.; Pandya, A.G. Melasma in Latina patients: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire in Spanish language. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogramaci, A.C.; Havlucu, D.Y.; Inandi, T.; Balkrishnan, R. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for the Turkish language: The MelasQoL-TR study. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2009, 20, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Garg, S.; Dominguez, A.; Balkrishnan, R.; Jain, R.K.; Pandya, A.G. Development and validation of a Hindi language health-related quality of life questionnaire for melasma in Indian patients. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2016, 82, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Ying, J.; Cai, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Xiang, W. Evaluating the quality of life among melasma patients using the MELASQoL scale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Lv, X.; Chen, K. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Herbal Drugs Used as Adjunctive Therapy for Melasma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9628319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbechie-Godec, O.A.; Elbuluk, N. Melasma: An Up-to-Date Comprehensive Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2017, 7, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlova, N.C.; Akintilo, L.O.; Taylor, S.C. Prevalence of pigmentary disorders: A cross-sectional study in public hospitals in Durban, South Africa. Int. J. Women's Dermatol. 2019, 5, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Doraiswamy, C.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Du, Z.; Vasantharaghavan, R.; Joshi, M.K. Facial skin characteristics and concerns in Indonesia: A cross-sectional observational study. Skin. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, H.; Yörük, S. Risk factors of striae gravidarum and chloasma melasma and their effects on quality of life. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, W.Q.; Fang, Q.Q.; Zhao, W.Y.; Zhao, Q.M.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.-W. Tranexamic Acid for Adults with Melasma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1683414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, P.E.; Ijaz, S.; Nashawati, R.; Kwak, D. New oral and topical approaches for the treatment of melasma. Int. J. Women's Dermatol. 2019, 5, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Wu, H.; Liang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhuo, F. Comparison of the Efficacy of Melasma Treatments: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 713554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Handog, E.; Das, A.; Bansal, A.; Macarayo, M.; Keshavmurthy, V.; Narayan, V.; Jagadeesan, S.; Pipo, E., 3rd; Ibaviosa, G.M.; et al. Topical and systemic therapies in melasma: A systematic review. Ind. Dermatol. Online J. 2023, 14, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Du, X.; Shen, S.; Song, X.; Xiang, W. Body dysmorphic disorder symptoms in patients with melasma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, I.; Cestari, T.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Azulay-Abulafia, L.; Bezerra Trindade Neto, P.; Hexsel, D.; Machado-Pinto, J.; Muñoz, H.; Rivitti-Machado, M.C.; Sittart, J.A.; et al. Preventing melasma recurrence: Prescribing a maintenance regimen with an effective triple combination cream based on long-standing clinical severity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 26, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, F.M.; Cestari, T.F.; Leopoldo, L.R.; Paludo, P.; Boza, J.C. Effect of melasma on quality of life in a sample of women living in southern Brazil. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harumi, O.; Goh, C.L. The Effect of Melasma on the Quality of Life in a Sample of Women Living in Singapore. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2016, 9, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, P.; Sharma, Y.K.; Patvekar, M.A.; Gupta, A. Correlating Impairment of Quality of Life and Severity of Melasma: A Cross-sectional Study of 141 Patients. Indian J. Dermatol. 2018, 63, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofana, N.; Paulse, M.; Gqaleni, N.; Makgobole, M.U.; Pillay, P.; Hussein, A.; Dlova, N.C. The Effect of Melasma on the Quality of Life in People with Darker Skin Types Living in Durban, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Awais, M.; Ilyas, M.; Shahzad, A.; Azfar, N.A. Correlation between quality of life and clinical severity of melasma in Pakistani women. J. Pak. Assoc. Dermatol. 2022, 32, 683–689. [Google Scholar]

- Yalamanchili, R.; Shastry, V.; Betkerur, J. Clinico-epidemiological Study and Quality of Life Assessment in Melasma. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akabane, A.; Almeida, I.; Simão, J. Analysis of melasma quality OF life scales (MELASQoL and DLQI) and MASI in Polypodium Leucotomos treated patients. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2017, 9, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.; Coqueiro, R.D.S.; Pithon, M.M.; Leite, M.F. Peeling with retinoic acid in microemulsion for treatment of melasma: A double-blind randomized controlled clinical study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, E.; Costa, A.; Jorge, A.; Júnior, J.; Szrajbman, M.; Sant’Anna, B. Monocentric prospective study for assessing the efficacy and tolerability of a cosmeceutical formulation in patients with melasma. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2016, 8, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevi, A.; Ustuner, P.; Ozdemir, M. Salicylic acid peeling combined with vitamin C mesotherapy versus salicylic acid peeling alone in the treatment of mixed type melasma: A comparative study. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2017, 9, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtyari, L.; Shirbeigi, L.; Tabarrai, M.; Rahimi, R.; Ayatollahi, A. Efficacy of a Polyherbal Syrup Containing Lemon Balm, Damask Rose, and Fennel to Treat Melasma: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2023, 18, e138392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Hanumanthu, V.; Thakur, V.; Bishnoi, A.; Vinay, K.; Kumar, A.; Parsad, D.; Kumaran, M.D. A randomized, open-label study to compare two different dosing regimens of oral tranexamic acid in treatment of moderate to severe facial melasma. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, E.I.; Torloni, L.; Fernandes, P.B.; de Campos, M.; Gonzaga, M.; Silva, F.C.; Nasario, J.P.S.; Guerra, L.F.; Csipak, A.R.; Castilho, V.C. Combination of 5% cysteamine and 4% nicotinamide in melasma: Efficacy, tolerability, and safety. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, S.; Sahu, P.; Yadav, M.; Jain, V.K. Clinical Efficacy and Safety on Combining 20% Trichloroacetic Acid Peel with Topical 5% Ascorbic Acid for Melasma. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, WC08–WC11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragoso-Covarrubias, C.E.; Tirado, A.; Ponce-Olivera, R.M. Efficacy and safety of the combination of arbutin 5% + glycolic acid 10% + kojic acid 2% versus hydroquinone 4% cream in the management of facial melasma in Mexican women with Fitzpatrick skin type III-IV. Dermatol. Rev. Mex. 2015, 59, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ojeda, A.; Cervantes-Guevara, G.; Chejfec-Ciociano, J.M.; Álvarez-Villaseñor, A.S.; Cervantes-Cardona, G.A.; Acevedo-Guzman, D.; Puebla-Mora, A.G.; Cortés-Lares, J.A.; Chávez-Tostado, M.; Cervantes-Pérez, E.; et al. Treatment of melasma with platelet-rich plasma: A self-controlled clinical trial. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.W.; Oh, D.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.W.; Park, S.W. Clinical efficacy of 25% L-ascorbic acid (C’ensil) in the treatment of melasma. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2009, 13, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikati, J.; Bcherawi, N.E.L.; Khater, J.A.; Maria, S.D.I.B.; Kechichian, E.; Helou, J. Combination Topical Tranexamic Acid and Vitamin C for the Treatment of Refractory Melasma. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2023, 16, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawardani, A.; Paramitasari, A.R.; Dewi, S.R.; Betaubun, A.I. The application of liposomal azelaic acid, 4-n butyl resorcinol and retinol serum enhanced by microneedling for treatment of malar pattern melasma: A case series. Dermatol. Rep. 2019, 11, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.L.; Pons, F.; Agopian, L.; Nathalie, P.; De Belilovsky, C.; Chadoutaud, B.; Msika, P. Effectiveness of a new depigmenting trio, Melanex® Trio 1 in melasma: Clinical and biometrological results, quality of life, image analysis. Nouv. Dermatol. 2006, 25, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, E.V.A.; Lima, M.; Paixao, M.P.; Miot, H.A. Assessment of the effects of skin microneedling as adjuvant therapy for facial melasma: A pilot study. BMC Dermatol. 2017, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.B.; Dias, J.A.F.; Cassiano, D.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Bagatin, E.; Miot, L.D.B.; Miot, H.A. A comparative study of topical 5% cysteamine versus 4% hydroquinone in the treatment of facial melasma in women. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.B.; Dias, J.A.F.; Cassiano, D.P.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Miot, L.D.B.; Bagatin, E.; Miot, H.A. Efficacy and safety of topical isobutylamido thiazolyl resorcinol (Thiamidol) vs. 4% hydroquinone cream for facial melasma: An evaluator-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.B.; Dias, J.A.F.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Miot, L.D.B.; Miot, H.A. French maritime pine bark extract (pycnogenol) in association with triple combination cream for the treatment of facial melasma in women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, G.M.; Borges, M.F.M.; Queiroz, A.R.C.; Capp, A.A.; Pedrosa, S.V.; Diniz, M.S. Double-blind randomized study of 5% and 10% retinoic acid peels in the treatment of melasma: Clinical evaluation and impact on the quality of life. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2011, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni, A.P.; Lorenzini, F.; Lipnharski, C.; Weber, M.; Nogueira, J.; Rizzati, K. Estudo comparativo, split face entre luz intensa pulsada com modo pulse-in-pulse. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 10, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rico, J.C.; Chavez-Alvarez, S.; Herz-Ruelas, M.E.; Sosa-Colunga, S.A.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Suro-Santos, Y.; Martinez, O.V. Oral tranexamic acid with a triple combination cream versus oral tranexamic acid monotherapy in the treatment of severe melasma. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3451–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, C.A.S.; Delfes, M.F.Z.; Reis, L.M.; Garbers, L.E.; Passos, P.C.V.R.; Torre, D.S. The use of pycnogenol in the treatment of melasma. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 7, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Dayal, S. Most worthwhile superficial chemical peel for melasma of skin of color: Authors’ experience of glycolic, trichloroacetic acid, and lactic peel. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Dayal, S.; Bhardwaj, N. Topical 5% tranexamic acid with 30% glycolic acid peel: An useful combination for accelerating the improvement in melasma. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Ghunawat, S.; Narang, I.; Verma, S.; Garg, V.K.; Dua, R. Role of broad-spectrum sunscreen alone in the improvement of melasma area severity index (MASI) and Melasma Quality of Life Index in melasma. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherdin, U.; Burger, A.; Bielfeldt, S.; Filbry, A.; Weber, T.; Scholermann, A.; Wigger-Alberti, W.; Rippke, F.; Wilhelm, K.-P. Skin-lightening effects of a new face care product in patients with melasma. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2008, 7, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Mun, J.H.; Ko, H.C.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, M.B. Korean red ginseng powder in the treatment of melasma: An uncontrolled observational study. J. Ginseng Res. 2011, 35, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Xiang, W. Comparative study of melasma in patients before and after treatment based on lipomics. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, P.E.; Yamada, N.; Bhawan, J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2005, 27, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcantara, G.P.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Olivatti, T.O.F.; Yoshida, M.M.; Miot, H.A. Evaluation of ex vivo melanogenic response to UVB, UVA, and visible light in facial melasma and unaffected adjacent skin. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollo, C.F.; Miot, L.D.B.; Meneguin, S.; Miot, H.A. Factors associated with quality of life in facial melasma: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handog, E.B.; Datuin, M.S.; Singzon, I.A. An open-label, single-arm trial of the safety and efficacy of a novel preparation of glutathione as a skin-lightening agent in Filipino women. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Batista, I.; Ramos, K.; Jesus, L.; Carneiro, M. Nutricosmético no tratamento de melasma. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e50611730451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.L.; Chuah, S.Y.; Tien, S.; Thng, G.; Vitale, M.A.; Delgado-Rubin, A. Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Polypodium Leucotomos Extract in the Treatment of Melasma in Asian Skin: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2018, 11, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.; Baek, H.S.; Joo, Y.H.; Lee, C.S.; Shin, H.-J.; Park, Y.-H.; Kim, B.J.; Shin, S.S. Antimelanogenic activity of a novel adamantyl benzylbenzamide derivative, AP736: A randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled comparative clinical trial performed in patients with hyperpigmentation during the summer. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, e321–e326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basri, D.F.; Lew, L.C.; Muralitharan, R.V.; Nagapan, T.S.; Ghazali, A.R. Pterostilbene Inhibits the Melanogenesis Activity in UVB-Irradiated B164A5 Cells. Dose Response 2021, 19, 15593258211047651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.S.; Kim, J.H. Antimelanogenic activity of patuletin from Inula japonica flowers in B16F10 melanoma cells and zebrafish embryos. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 4457–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.; Lee, S.E. Antimelanogenic Effects of Curcumin and Its Dimethoxy Derivatives: Mechanistic Investigation Using B16F10 Melanoma Cells and Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos. Foods 2023, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.C.C.; Ribeiro, M.M.; da Costa, N.S.; Galiciolli, M.E.A.; Souza, J.V.; Irioda, A.C.; Oliveira, C.S. Analysis of the antimelanogenic activity of zinc and selenium in vitro. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, R.; Sharad, J.; Vedamurthy, M. Chemical peels and fillers-incorporating scientific evidence in clinical practice. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2012, 5, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.H.; Hwang, Y.J.; Lee, S.K.; Park, K.C. Heterogeneous Pathology of Melasma and Its Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Country | Sample ** Sex (n) Age (Years) | MASI | MELASQoL | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominguez et al. [13] | USA | NI (43) | 12.5 ± 6.3 | 47.7 ± 17.9 | Data from previously treated melasma patients. Pearson’s correlation between MASI and MELASQoL showed a positive moderate correlation. |

| NI (56) 41.1 ± 6.8 | 8.7 ± 5.7 | 35.7 ± 18.3 | Data from patients who have never been treated for melasma. Pearson’s correlation between MASI and MELASQoL showed a positive moderate correlation. | ||

| Freitag et al. [28] | Brazil | F (84) | 10.6 ± 6.6 | 37.5 ± 15.2 | There was no correlation between MELASQoL and MASI scores. |

| 41.1 ± 6.8 | |||||

| Harumi, Goh [29] | Singapore | F (49) | 12.1 ± 6.5 | 25.6 ± 15.3 | There was no correlation between MASI and MELASQoL. |

| 56.6 ± 9.1 | |||||

| Jusuf et al. [7] | Indonesia | NI (30) | 13.7 ± 5.0 | 40.0 ± 12.1 | There was no correlation between the MELASQoL and MASI scores. |

| 39.3 ± 4.7 | |||||

| Kothari et al. [30] | India | F (105) | 9.1 ± 6.1 | 28.6 ± 13.0 | There was no correlation between the MELASQoL and MASI scores. |

| M (36) | |||||

| 32.3 ± 7.4 | |||||

| Mpofana et al. [31] | South Africa | F (150) 47.3 ± 10.2 | 40.6 ± 4.9 | 56.3 ± 7.4 | Pearson correlation matrix was used to establish the presence of multicollinearity between predictor variables. The analysis concluded a positive relationship between MASI and MELASQoL. |

| Qayyum et al. [32] | Pakistan | F (80) 32.4 ± 7.5 | 15.8 ± 8.9 | 46.5 ± 16.9 | Spearman correlation showed a significantly strong positive correlation between MASI and MELASQoL. |

| Yalamanchili et al. [33] | India | F (95) 32.4 ± 7.0 | 5.7 | 28.3 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. |

| M (45) | |||||

| 20.0–68.0 | |||||

| Zhu et al. [26] | China | F (470) 39.7 ± 6.1 | 13.3 ± 7.2 | 23.2 ± 9.9 | There was no correlation between the MELASQoL and MASI scores. |

| Reference/Country/Treatment | Sample ** Sex (n) Age (Years) | MASI | MELASQoL | Main Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Akabane et al. [34] | F (9) 37.2 ± 6.8 | 11.8 ± 7.4 | 11.0 ± 6.2 | 53.4 ± 8.5 | 38.9 ± 14.1 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Brazil | ||||||||

| Polypodium orally, twice a day for 6 weeks. | ||||||||

| Andrade et al. [35] | F (60) | A: 15.2 ± 10.0 | A: 11.2 ± 8.9 | A: 41.3 ± 8.9 | A: 36.9 ± 6.3 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Brazil | 34.2 ± 7.8 | B: 13. ± 7.8 | B: 5.2 ± 4.6 | B: 44.9 ± 6.5 | B: 31.7 ± 6.0 | |||

| A: 1% retinoic acid peeling in a conventional vehicle; B: 1% retinoic acid peeling in microemulsion; Four peeling sessions fortnightly on days 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60. | ||||||||

| Arellano et al. [27] Brazil and Mexico | F (231) M (11) 41.2 | A: 15.0 ± 6.1 B: 15.8 ± 7.1 | A: 2.3 ± 2.4 B: 2.1 ± 2.3 | A: 42.7 ± 15.3 B: 41.1 ± 14.7 | A: 29.0 ± 18.4 A: 27.7 ± 16.2 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: Cream containing hydroquinone, fluocinolone acetonide, and tretinoin once a day for 8 weeks. Plus a maintenance phase of the same cream twice weekly for 24 weeks. B: Cream containing hydroquinone, fluocinolone acetonide, and tretinoin once a day for 8 weeks. Plus a maintenance phase of the same cream in a tapering regimen (3 times a week–1st month, 2 times a week –2nd month, 1 time a week–4 to 6th month). | ||||||||

| Ayres et al. [36] | NI (33) | 15.5 | 8.8 | 45.4 | 34.6 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Brazil | 43.0 | |||||||

| Cream containing ellagic acid, hydroxyphenoxy propionic acid, yeast extract, and salicylic acid twice a day for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Balevi et al. [37] | F (50) | A: 16.7 ± 11.5 | A: 5.3 ± 2.6 | A: 42.8 ± 15.1 | A: 20.8 ± 7.8 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Peru | 36.3 ± 10.2 | B: 15.8 ± 10.5 | B: 13.9 ± 10.8 | B: 34.7 ± 14.8 | B: 23.6 ± 11.8 | |||

| A: Salicylic acid peel and intra-lesional application of vitamin C every 2 weeks for 8 weeks. B: Salicylic acid peel every 2 weeks for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Bakhtyari et al. [38] | F (55) | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 3.8 ± 2.0 | 24.1 ± 10.0 | 21.1 ± 9.3 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Iran | 20.0–40.0 | |||||||

| Polyherbal syrup: 10 mL thrice daily before meals for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Bhattacharjee et al. [39] India | A: F (22) M (3) 36.8 ± 5.7 B: F (24) M (1) 37.6 ± 7.2 | A: 9.6 ± 3.6 B: 11.4 ± 4.5 | A: 4.8 ± 2.2 B: 6.8 ± 3.4 | A: 44.2 ± 12.6 B: 41.1 ± 12.4 | A: 22 ± 10.2 B: 22.9 ± 10.9 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 250 mg oral tranexamic acid twice daily; B: 500 mg oral tranexamic acid twice daily, followed by 12 weeks of follow-up. | ||||||||

| Cestari et al. [12] Brazil | F (135) M (4) 42.5 ± 7.5 | 13.3 ± 6.7 | 4.1 ± 3.7 | 44.4 ± 14.9 | 24.3 ± 15.5 | Pearson’s correlation between MASI and MELASQOL was positive correlated. | ||

| Cream containing hydroquinone, fluocinolone acetonide, and tretinoin once a day for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Crocco et al. [40] Brazil | F (35) 38.5 ± 11.5 | 6.7 ± 3.2 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 51.0 ± 11.4 | 35 ± 18.4 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Cream containing cysteamine and nicotinamide: Progressive application (60 min in the first month, 120 min in the second month, 180 min in the third month) for 90 days | ||||||||

| Dayal et al. [41] India | F (56) | A: 23.5 ± 4.6 B: 23.6 ± 4.1 | A: 9.5 ± 5.3 B: 15.1 ± 4.4 | A: 42.7 ± 9.3 * B: 42.4 ± 8.7 * | A: 16.6 ± 8.0 * B: 25.9 ± 8.2 * | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| M (4) | ||||||||

| 31.7 ± 5.9 | ||||||||

| A: Trichloroacetic acid peel every 2 weeks. Plus, a cream containing vitamin C once a day for 12 weeks. B: Trichloroacetic acid peel every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Fragoso-Covarrubias et al. [42] Mexico | F (33) 45.4 ± 7.2 | 10.7 ± 5.2 | 7.2 ± 4.2 | 40.2 ± 21.1 | 33.1 ± 17.8 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Cream containing arbutin, glycolic acid, and kojic acid once a day for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| González-Ojeda et al. [43] Mexico | F (20) 41.0 ± 7.0 | 15.5 ± 8.4 | 9.5 ± 7.2 | 42.0 ± 14.8 | 16.6 ± 7.2 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Platelet-Rich Plasma: Three sessions every 15-day intervals. | ||||||||

| Hwang et al. [44] South Korea | F (39) 26.0–52.0 | 15.6 | 12.0 | 39.8 | 36.2 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Serum containing vitamin C, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, and dimethyl isosorbide twice daily for 16 weeks. | ||||||||

| Kaikati et al. [45] Lebanon | F (10) 45.9 ± 11.3 | 12.8 ± 3.9 | 3.4 ± 1.7 | 35.2 ± 16.0 | 24.9 ± 13.9 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Cream containing tranexamic acid and vitamin C for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Kusumawardani et al. [46] Indonesia | F (3) 40.0–45.0 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 55.3 ± 3.3 | 19.0 ± 5.8 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Serum containing azelaic acid, 4-n butyl resorcinol, and retinol combined with a microneedling session. | ||||||||

| Levy et al. 2006 [47] France | F (19) 42.7 | 20.3 | 10.2 | 50.8 * | 42.3 * | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. * values were divided by 10 | ||

| Cream containing undecyl-dimethyl-oxazoline, undecyl-enoyl-phenylalanine, vitamin C, and vitamin E, twice a day for 16 weeks. | ||||||||

| Lima et al. [48] Brazil | F (6) 34.0–46.0 | 37.1 ± 8.2 | 11.0 ± 2.9 | 70.0 | 32.0 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Microneedling sessions every 30 days. Plus, a cream containing hydroquinone, fluocinolone acetonide, and tretinoin once a day for 4 weeks. | ||||||||

| Lima et al. [49] Brazil | F (40) 43.0 ± 6.0 | A: 9.0 (6.0–12.0) B: 6.0 (3.0–8.0) | A: 5.0 (4.0–8.0) B: 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | A: 55.0 (45.0–60.0) B: 45.0 (37.0–51.0) | A: 48.0 (26.0–53.0) B: 29.0 (16.0–45.0) | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: Cream containing cysteamine, nightly application for 15 min to 2 h + 120 days with sun protection factor 50 sunscreen. with sun protection factor 50 sunscreen; B: Cream containing 4% hydroquinone, nightly application + 120 days with sun protection factor 50 sunscreen. | ||||||||

| Lima et al. [50] Brazil | F (50) 43.0 ± 6.0 | A: 6.9 ± 3.6 B: 7.2 ± 3.4 | A: 4.1 ± 2.6 B: 5.0 ± 3.1 | A: 49.8 ± 12.9 B: 45.0 ± 14.2 | A: 36.1 ± 15.2 B: 31.0 ± 15.1 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: Cream containing thiamidol, double layer application twice a day + SPF 60 sunscreen every 3 h for 90 days; B: Cream containing 4% hydroquinone, once at bedtime + SPF 60 sunscreen every 3 h for 90 days. | ||||||||

| Lima et al. [51] Brazil | F (44) 39.0 ± 7.0 | A: 9.1 ± 4.1 B: 9.2 ± 4.1 | A: 4.6 ± 3.4 B: 6.4 ± 4.3 | A: 43.9 ± 13.0 B: 44.4 ± 10.9 | A: 25.5 ± 17.2 B: 30.3 ± 15.7 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 75 mg Pycnogenol, orally, twice a day. Plus a cream, daily, containing hydroquinone, tretinoin, and fluocinolone for 15 weeks. B: Cream, daily, containing hydroquinone, tretinoin, and fluocinolone for 15 weeks. | ||||||||

| Magalhães et al. [4] Brazil | F (31) 30.0–59.0 | 15.0 ± 7.0 | 8.0 ± 4.7 | 36.3 ± 13.8 | 31.7 ± 14.0 | There was no correlation between MASI and MELASQOL. | ||

| Lactic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Magalhães et al. [52] Brazil | F (27) M (3) | A: 15.6 ± 8.5 B: 11.1 ± 5.1 | A: 8.9 ± 7.0 B: 6.4 ± 3.5 | A: 34.3 ± 13.8 B: 40.9 ± 17.7 | A: 30.1 ± 12.4 A: 31.4 ± 19.0 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 5% retinoic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 6 weeks; B: 10% retinoic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 6 weeks. | ||||||||

| Manzoni et al. [53] Brazil | F (14) 41.0 ± 4.6 | 8.4 ± 4.0 | 5.5 ± 3.4 | 42.2 ± 14.9 | 33.7 ± 11.6 | There was no correlation between MELASQOL and MASI scores. | ||

| A: Intense pulsed light with pulse-in-pulse mode every 2 weeks for 8 weeks in the left hemiface. B: Retinoic acid peel every 2 weeks during 8 weeks in the right hemiface. Obs.: The treatments were applied to the same individual. The final values were the mean of A and B values. | ||||||||

| Martinez-Rico et al. [54] Mexico | A: F(22) 40.4 ± 3.9 B: F(22) 42.8 ± 4.9 | A:10.4 B:10.8 | A: 3.6 B: 4.2 | A: 48.9 B: 42.9 | A: 31.1 B: 30.6 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 325 mg oral tranexamic acid every 12 h + fluocinolone-based triple combination cream every 24 h; B: 325 mg oral tranexamic acid every 12 h for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Pinto et al. [55] Brazil | F (18) 42.0 ± 7.6 | 8.5 ± 4.4 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 41.3 ± 13.3 | 29.4 ± 14.4 | There was no correlation between MELASQOL and MASI scores. | ||

| Pycnogenol, orally, once a day for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Sahu and Dayal [56] India | F (74) M (6) A: 31.6 ± 5.6 B: 30.9 ± 5.9 C: 31.6 ± 6.3 | A: 22.6 ± 4.6 B: 22.9 ± 4.4 C: 22.8 ± 3.6 | A: 12.4 ± 4.3 B: 13.2 ± 4.5 C: 15.1 ± 3.7 | A: 38.4 ± 9.8 B: 39.6 ± 8.2 C: 39.9 ± 8.1 | A: 20.2 ± 6.7 B: 26.2 ± 6.5 C: 23.7 ± 8.6 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 30% glycolic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. B: 92% lactic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. C: 15% trichloroacetic acid every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Sahu et al. [57] India | F (60) A: 34 ± 5.75 B: 32.4 ±6.2 | A: 24.6 ± 4.1 B: 23.4 ± 3.9 | A: 11.6 ± 4.6 B: 13.2 ± 4.3 | A: 46.0 ± 11.5 B: 45.9 ± 9.0 | A: 21.5 ± 4.9 B: 24.1 ± 6.2 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| A: 30% glycolic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks. Plus, a cream containing tranexamic acid (twice a day) for 12 weeks. B: 30% glycolic acid chemical peel every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Sarkar et al. [58] India | F (80) M (20) 33.3 ± 6.7 | 12.4 ± 14.7 | 9.1 ± 4.7 | 47.2 ± 14.0 | 38.1 ± 14.2 | There was a positive correlation between MELASQOL and MASI scores | ||

| Sunscreen with sun protection factor 19 and PA+++, thrice a day, for 12 weeks. | ||||||||

| Scherdin et al. [59] Germany | F (19) M (1) 41.9 ± 11.9 | 8.4 | 4.8 | 28.3 | 19.4 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Cream contains octadecene dioic acid, tocopherol, and sun protection factor 30 once a day for 8 weeks. | ||||||||

| Song et al. [60] South Korea | F (25) 20.0–60.0 | 8.8 ± 6.6 | 5.5 ± 3.9 | 46.6 ± 12.7 | 32.0 ± 13.8 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Korean red ginseng powder, orally, for 24 weeks. | ||||||||

| Zhu et al. [61] China | F (15) 40.9 ± 1.4 | 20 ± 4.7 | 11.7 ± 3.8 | 33.5 ± 13.1 | 20.3 ± 8.9 | The authors did not carry out a correlation test. | ||

| Oral tranexamic acid plus a cream containing hydroquinone for 3 weeks of treatment. | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, M.M.; da Silva, A.C.C.; Dalagrana, H.; Galiciolli, M.E.A.; Irioda, A.C.; Garlet, Q.I.; Oliveira, C.S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatments on Melasma Area Severity Index and Quality of Life. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121619

Ribeiro MM, da Silva ACC, Dalagrana H, Galiciolli MEA, Irioda AC, Garlet QI, Oliveira CS. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatments on Melasma Area Severity Index and Quality of Life. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121619

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Milena Mariano, Ana Cleia Cardoso da Silva, Heloise Dalagrana, Maria Eduarda A. Galiciolli, Ana Carolina Irioda, Quelen Iane Garlet, and Cláudia Sirlene Oliveira. 2025. "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatments on Melasma Area Severity Index and Quality of Life" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121619

APA StyleRibeiro, M. M., da Silva, A. C. C., Dalagrana, H., Galiciolli, M. E. A., Irioda, A. C., Garlet, Q. I., & Oliveira, C. S. (2025). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatments on Melasma Area Severity Index and Quality of Life. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121619