A Biomimetic Macrophage-Membrane-Fused Liposomal System Loaded with GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid for Targeted Anti-Atherosclerosis Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid Construction and Verification

2.2. Macrophage Membrane Isolation

2.3. Verification of Lipid Membrane and Macrophage Membrane Fusion

2.4. Preparation of GVs-HV@Lipo

2.5. Preparation and Characterization of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.6. Cellular Uptake of GVs-HV@Lipo and GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.7. In Vitro Lysosomal Escape Ability of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.8. Transfection Efficiency of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.9. Expression of Gas Vesicles In Vitro

2.10. In Vitro Lipid-Lowering and Anti-Inflammatory Ability of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.11. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo by MTT Assay

2.12. Ethics Statement

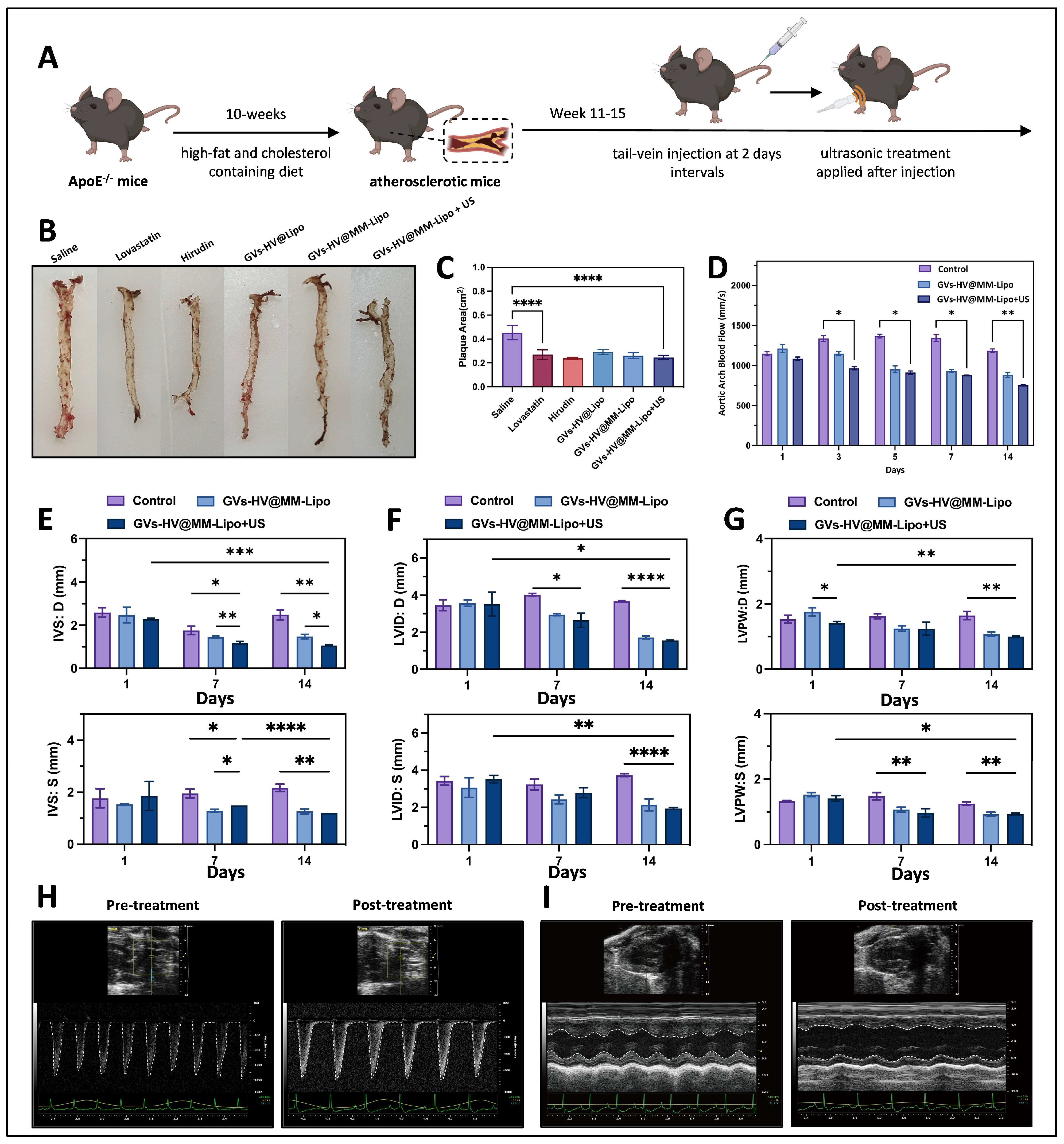

2.13. GVs-HV@MM-Lipo Relieves Plaque Symptoms In Vivo

2.14. In Vivo Anti-Atherosclerosis and Anti-Inflammatory Study of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.15. In Vivo Biosafety Profile of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Construction and Verification of GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid

3.2. Construction and Characterization of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

3.3. Uptake and Intracellular Transport of GVs-HV@MM-Lipo

3.4. GVs-HV@MM-Lipo Mediated Linkage of Hirudin and Gas Vesicles

3.5. GVs-HV@MM-Lipo Relieves Plaque Symptoms and Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duivenvoorden, R.; Senders, M.L.; van Leent, M.M.T.; Pérez-Medina, C.; Nahrendorf, M.; Fayad, Z.A.; Mulder, W.J.M. Nanoimmunotherapy to treat ischaemic heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.J.; Tall, A.R. Disordered haematopoiesis and athero-thrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, A.; Bhatt, L.K.; Johnston, T.P. Evolving targets for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 187, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis, A.P.; Trainor, P.J.; Thanassoulis, G.; Brumback, L.C.; Post, W.S.; Tsai, M.Y.; Tsimikas, S. Atherothrombotic factors and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, L.; Antignani, P.L.; Gupta, A.; Cau, R.; Paraskevas, K.I.; Poredos, P.; Wasserman, B.; Kamel, H.; Avgerinos, E.D.; Salgado, R.; et al. International Union of Angiology (IUA) consensus paper on imaging strategies in atherosclerotic carotid artery imaging: From basic strategies to advanced approaches. Atherosclerosis 2022, 354, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatana, C.; Saini, N.K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Saini, V.; Sharma, A.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Mechanistic Insights into the Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein-Induced Atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5245308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Luo, J.Y.; Li, B.; Tian, X.Y.; Chen, L.J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Deng, D.; Lau, C.W.; Wan, S.; et al. Integrin-YAP/TAZ-JNK cascade mediates atheroprotective effect of unidirectional shear flow. Nature 2016, 540, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, Y.; Tian, M.; Deng, Q.; Qin, X.; Lu, H.; Gao, J.; Chen, M.; Weinstein, L.S.; Zhang, M.; et al. Gsα Regulates Macrophage Foam Cell Formation During Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, e34–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, B.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wei, Y. Reducing the Damage of Ox-LDL/LOX-1 Pathway to Vascular Endothelial Barrier Can Inhibit Atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 7541411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Hang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, C. Osteoporosis remission via an anti-inflammaging effect by icariin activated autophagy. Biomaterials 2023, 297, 122125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Khan, G.J.; Zhu, J.; Liu, F.; Duan, H.; Li, L.; Zhai, K. Targeted intervention of natural medicinal active ingredients and traditional Chinese medicine on epigenetic modification: Possible strategies for prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis. Phytomedicine 2024, 122, 155139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Kumar, S.; Frederiksen, J.W.; Kolyadko, V.N.; Pitoc, G.; Layzer, J.; Yan, A.; Rempel, R.; Francis, S.; Krishnaswamy, S.; et al. Aptameric hirudins as selective and reversible EXosite-ACTive site (EXACT) inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Feng, M.; Wei, X.; Cheng, C.; He, K.; Jiang, T.; He, B.; Gu, Z. In situ formed depot of elastin-like polypeptide-hirudin fusion protein for long-acting antithrombotic therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2314349121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Feng, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhang, C.; Mo, R. Self-regulated hirudin delivery for anticoagulant therapy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc0382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xia, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Yang, S.; Yu, J.; Liang, Q.; Shen, T.; Yu, M.; Zhao, B. Design and fabrication of r-hirudin loaded dissolving microneedle patch for minimally invasive and long-term treatment of thromboembolic disease. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Li, M.; Wen, Z.; Han, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, J.; Pan, Y. Efficacy and potential mechanism of atherosclerosis prevention by the active components of leech based on network pharmacology combined with animal experiments. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, W.; Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Han, H. Biomimetic Nanoplatelets to Target Delivery Hirudin for Site-Specific Photothermal/Photodynamic Thrombolysis and Preventing Venous Thrombus Formation. Small 2022, 18, e2203184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabuncu, S.; Yildirim, A. Gas-stabilizing nanoparticles for ultrasound imaging and therapy of cancer. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, I.A.; Ballard, J.R.; Casper, A.J.; Liu, D.; Mitchell, T.; Ebbini, E.S. Feasibility of targeting atherosclerotic plaques by high-intensity-focused ultrasound: An in vivo study. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 24, 1880–1887.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, F. Distribution, formation and regulation of gas vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Zion, A.; Nourmahnad, A.; Mittelstein, D.R.; Shivaei, S.; Yoo, S.; Buss, M.T.; Hurt, R.C.; Malounda, D.; Abedi, M.H.; Lee-Gosselin, A.; et al. Acoustically triggered mechanotherapy using genetically encoded gas vesicles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaridas, R.; Vidal-Sabanés, M.; Ruiz-Mitjana, A.; Perramon-Güell, A.; Megino-Luque, C.; Llobet-Navas, D.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Egea, J.; Encinas, M.; Bardia, L.; et al. Transient and DNA-free in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for flexible modeling of endometrial carcinogenesis. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, Y.G.; Lee, J.M.; Chung, E.; Lee, J.; Lim, K.; Cho, S.I.; Kim, J.S. Base editing in human cells with monomeric DddA-TALE fusion deaminases. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luiz, M.T.; Dutra, J.A.P.; Tofani, L.B.; de Araújo, J.T.C.; Di Filippo, L.D.; Marchetti, J.M.; Chorilli, M. Targeted Liposomes: A Nonviral Gene Delivery System for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, J.; Sun, L.; Shan, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L. Artificial Lipids and Macrophage Membranes Coassembled Biomimetic Nanovesicles for Antibacterial Treatment. Small 2022, 18, e2201280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; He, M.; Wang, J.; Ladds, M.; Lianoudaki, D.; Sedimbi, S.K.; Lane, D.P.; Westerberg, L.S.; et al. CD36 and LC3B initiated autophagy in B cells regulates the humoral immune response. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3577–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Targeting macrophages using nanoparticles: A potential therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 3284–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tang, M.; Ho, W.; Teng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Bu, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.Q. Modulating Plaque Inflammation via Targeted mRNA Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 17721–17739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, T.; Maruf, A.; Qin, X.; Luo, L.; Zhong, Y.; Qiu, J.; McGinty, S.; Pontrelli, G.; et al. Macrophage membrane functionalized biomimetic nanoparticles for targeted anti-atherosclerosis applications. Theranostics 2021, 11, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; He, M.; Xu, F.; Fan, Y.; Jia, B.; Shen, M.; Wang, H.; Shi, X. Macrophage Membrane-Camouflaged Responsive Polymer Nanogels Enable Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Chemotherapy/Chemodynamic Therapy of Orthotopic Glioma. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 20377–20390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, C.; Kwong, C.H.T.; Yue, L.; Wan, J.B.; Lee, S.M.Y.; Wang, R. Treatment of atherosclerosis by macrophage-biomimetic nanoparticles via targeted pharmacotherapy and sequestration of proinflammatory cytokines. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yan, B.; Tian, X.; Liu, Q.; Jin, J.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. CD47/SIRPα pathway mediates cancer immune escape and immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3281–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Mi, C.L.; Cao, X.X.; Wang, T.Y. Progress of cationic gene delivery reagents for non-viral vector. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Zhao, D.; Yuan, Z.; Zeng, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; et al. M2 Macrophage Hybrid Membrane-Camouflaged Targeted Biomimetic Nanosomes to Reprogram Inflammatory Microenvironment for Enhanced Enzyme-Thermo-Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2304123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, F. Ultrasound molecular imaging of p32 protein translocation for evaluation of tumor metastasis. Biomaterials 2023, 293, 121974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.T.; Terwiel, D.; Evers, W.H.; Maresca, D.; Jakobi, A.J. Cryo-EM structure of gas vesicles for buoyancy-controlled motility. Cell 2023, 186, 975–986.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Son, G. Numerical investigation of two-microbubble collapse and cell deformation in an ultrasonic field. Ultrason. Sonochem 2023, 92, 106252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Mao, L.; Zeng, Q.; Zou, Y.; Xue, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, Q.; Yang, S.; et al. Hirudin inhibit the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes via suppressing oxidative stress and activating mitophagy. Heliyon 2023, 10, e23077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Dong, X.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Jin, M.; Zhang, P. Targeted delivery of berberine using bionic nanomaterials for Atherosclerosis therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Cinelli, M.A.; Kang, S.; Silverman, R.B. Development of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors for neurodegeneration and neuropathic pain. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6814–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.A.; Do, H.T.; Miley, G.P.; Silverman, R.B. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Regulation, structure, and inhibition. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 158–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, I.; Romano, E.; Fioretto, B.S.; El Aoufy, K.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Manetti, M. Lymphatic Endothelial-to-Myofibroblast Transition: A Potential New Mechanism Underlying Skin Fibrosis in Systemic Sclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.P. Mitochondria transfer and transplantation in human health and diseases. Mitochondrion 2022, 65, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Z.; Xie, M.; Hun, M.; Abdirahman, A.S.; Li, C.; Wu, F.; Luo, S.; Wan, W.; Wen, C.; Tian, J. Immunoregulatory Effects of Mitochondria Transferred by Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 628576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, M.; Shah, P.K. STOP the TRAFfic and Reduce the Plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Du, C.; Cui, C.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Kong, W.; et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell-derived hydrogen sulfide promotes atherosclerotic plaque stability via TFEB (transcription factor EB)-mediated autophagy. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2270–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Jang, S.; Zhu, J.; Qin, Q.; Sun, L.; Sun, J. Nur77 mitigates endothelial dysfunction through activation of both nitric oxide production and anti-oxidant pathways. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Long, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Han, H. Inhalable biomimetic nanomotor for pulmonary thrombus therapy. Nano Today 2024, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.H.; Zhang, H.T.; Wang, R.; Yan, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.C. Improving long circulation and procoagulant platelet targeting by engineering of hirudin prodrug. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hao, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Long, H.; Yan, F. Genetic Modulation of Biosynthetic Gas Vesicles for Ultrasound Imaging. Small 2024, 20, e2310008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; Ko, J.H.; Stordy, B.; Zhang, Y.; Didden, T.F.; Malounda, D.; Swift, M.B.; Chan, W.C.W.; Shapiro, M.G. Gas Vesicle-Blood Interactions Enhance Ultrasound Imaging Contrast. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 10748–10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Han, J.; Li, H.; Ma, X.; Tang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Z. Ultrasound mediated gold nanoclusters-capped gas vesicles for enhanced fluorescence imaging. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 43, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Jing, J.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, X.; Xian, Q.; Lei, T.; Zhu, J.; Wong, K.F.; Zhao, X.; Su, M.; et al. Nanobubble-actuated ultrasound neuromodulation for selectively shaping behavior in mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, D.P.; Bar-Zion, A.; Farhadi, A.; Shivaei, S.; Ling, B.; Lee-Gosselin, A.; Shapiro, M.G. Ultrasensitive ultrasound imaging of gene expression with signal unmixing. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Gu, W.; Yu, K.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, H.; Liu, L.; Li, F. A Biomimetic Macrophage-Membrane-Fused Liposomal System Loaded with GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid for Targeted Anti-Atherosclerosis Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121618

Zhang Y, Gu W, Yu K, Chen Q, Wang H, Wei Y, Zheng H, Zheng H, Liu L, Li F. A Biomimetic Macrophage-Membrane-Fused Liposomal System Loaded with GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid for Targeted Anti-Atherosclerosis Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121618

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuelin, Wenting Gu, Kailing Yu, Qihong Chen, Hong Wang, Yinghui Wei, Hangsheng Zheng, Hongyue Zheng, Lin Liu, and Fanzhu Li. 2025. "A Biomimetic Macrophage-Membrane-Fused Liposomal System Loaded with GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid for Targeted Anti-Atherosclerosis Therapy" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121618

APA StyleZhang, Y., Gu, W., Yu, K., Chen, Q., Wang, H., Wei, Y., Zheng, H., Zheng, H., Liu, L., & Li, F. (2025). A Biomimetic Macrophage-Membrane-Fused Liposomal System Loaded with GVs-HV Recombinant Plasmid for Targeted Anti-Atherosclerosis Therapy. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121618