Recent Developments in Pharmaceutical Spray Drying: Modeling, Process Optimization, and Emerging Trends with Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transport Phenomena in Spray Drying

2.1. Droplet Drying Process

2.2. Particle Formation Process

3. Process Parameters

4. Mathematical and Computational Modeling in Spray Drying

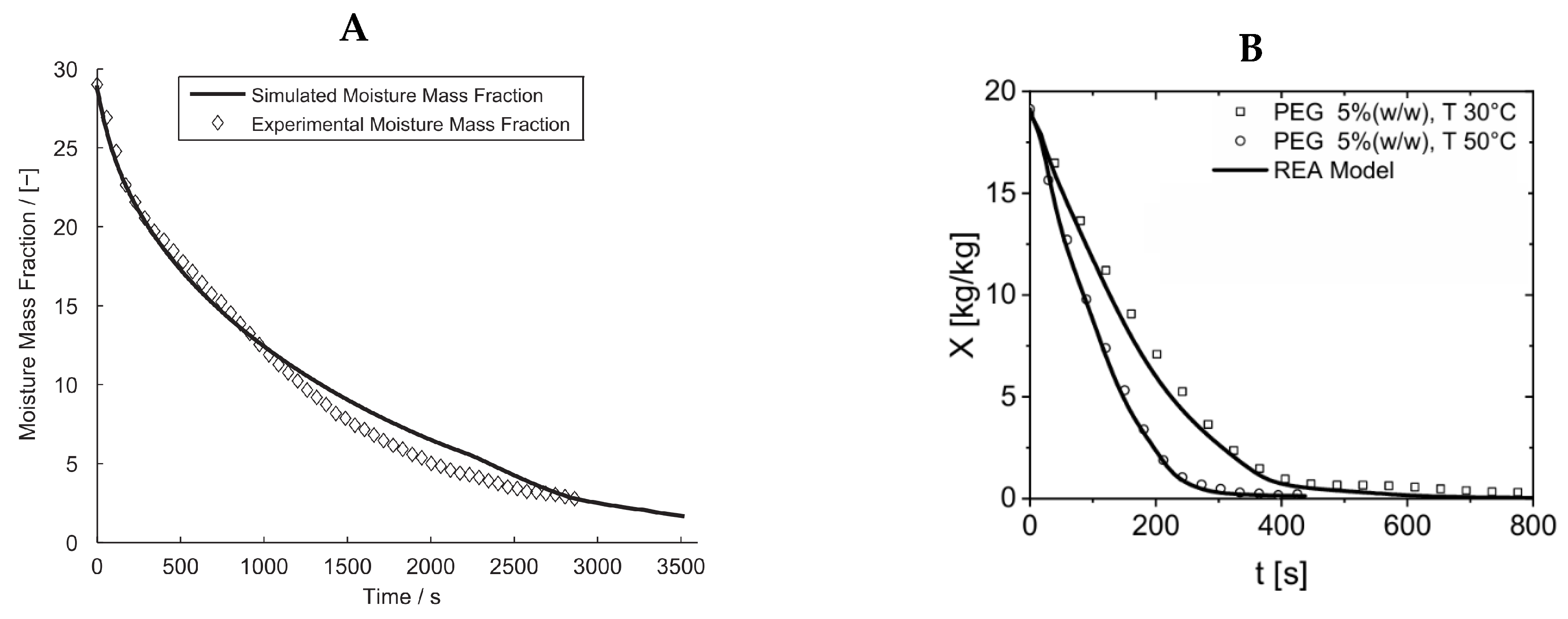

4.1. Single Droplet Modeling

4.2. CFD in Spray Drying

4.3. Limitations and Recommendations in CFD Modeling

5. Machine Learning-Based Predictive Models

5.1. Machine Learning Framework

| Machine Learning Models | Input Parameters Studied | Critical Quality Attributes Predicted | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble machine learning (EL) | Sonication time, extrusion temperature, and feed composition | Particle size, and polydispersity index (PDI) of liposomal particles, in vitro dissolution profile | [284,286] |

| Artificial neural network | Different types of drugs and excipients, carrier concentration, particle size, and morphology | Drug–excipient interactions, powder yield, emitted dose, fine particle fraction | [280,286,287] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Effects of the type of core and shell materials and their concentrations, effect of particle size | In vitro dissolution profile of sustained-release tablets, tablet tensile strength, and tablet brittleness index | [286] |

5.2. Hybrid ML Models

5.3. Limitations of Using ML/AI in Engineering

5.4. Comparative Analysis Between CFD and ML Models

| Characteristics | CFD Model | ML Model | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic insight | Simulates physical phenomena, droplet drying kinetics, and process robustness | Depends on data patterns and has less physical insight | [350,352] |

| Prediction accuracy | Good: Based on model validation and computational resources | Higher with substantial datasets | [349,351,352] |

| Computational expense | High: Particularly for industrial scale | Low: predictions are rapid upon training | [351,352] |

| Product quality prediction | Able to model the influence of operating parameters on powder properties | Able to enhance the prediction accuracy, but less mechanistic | [349,352,356] |

| Industrial Applicability | Limited due to scale and validation | Potential for automation and quick process optimization | [351,352] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Advanced Mesh Refinement |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| API | Active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CPP | Critical process parameters |

| CQA | Critical quality attributes |

| DoE | Design of Experiment |

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| DPI | Dry powder inhaler |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regression |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| Pe | Peclet number |

| QBD | Quality by Design |

| REA | Reaction Engineering Approach |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| RTD | Residence time distribution |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

References

- Sosnik, A.; Seremeta, K.P. Advantages and Challenges of the Spray-Drying Technology for the Production of Pure Drug Particles and Drug-Loaded Polymeric Carriers. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 223, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, E.A.; Soto-Cantu, E. Modern Developments in the Spray-Drying Industries. Recent Pat. Mater. Sci. 2011, 4, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamuthukumaran, M. Handbook on Spray Drying Applications for Food Industries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780429055133. [Google Scholar]

- Shishir, M.R.I.; Chen, W. Trends of Spray Drying: A Critical Review on Drying of Fruit and Vegetable Juices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.K.; Patil, V. Effect of Packaging Material on Storage Ability of Mango Milk Powder and the Quality of Reconstituted Mango Milk Drink. Powder Technol. 2013, 239, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.K.; Tan, C.P.; Manap, Y.A.; Muhialdin, B.J.; Hussin, A.S.M. Spray Drying for the Encapsulation of Oils—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, A.; Verruck, S.; Machado Canella, M.H.; Marchesan Maran, B.; Seigi Murakami, F.; de Avila Junior, B.; de Campos, C.E.M.; Hernandez, E.; Schwinden Prudencio, E. Current Knowledge about Physical Properties of Innovative Probiotic Spray-Dried Powders Produced with Lactose-Free Milk and Prebiotics. LWT 2021, 151, 112175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.; da Silva, N.R.; Silvério, S.C.; Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A. Chapter 17—Unit Operations for Extraction and Purification of Biological Products. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Sirohi, R., Pandey, A., Taherzadeh, M.J., Larroche, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 455–495. ISBN 978-0-323-91167-2. [Google Scholar]

- Erbay, Z.; Salum, P.; Bolat, E.B. 22—Drying of Dairy Products. In Drying Technology in Food Processing; Jafari, S.M., Malekjani, N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: London, UK, 2023; pp. 651–701. ISBN 978-0-12-819895-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, V.; Stramarkou, M.; Plakida, A.; Krokida, M. Optimization of Encapsulation of Stevia Glycosides through Electrospraying and Spray Drying. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 131, 107854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrasco, M.; Valdez-Baro, O.; Cabanillas-Bojórquez, L.A.; Bernal-Millán, M.J.; Rivera-Salas, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Heredia, J.B. Potential Agricultural Uses of Micro/Nano Encapsulated Chitosan: A Review. Macromol 2023, 3, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merivaara, A.; Zini, J.; Koivunotko, E.; Valkonen, S.; Korhonen, O.; Fernandes, F.M.; Yliperttula, M. Preservation of Biomaterials and Cells by Freeze-Drying: Change of Paradigm. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajashree, V.; Vijai Selvaraj, K.S.; Muthuvel, I.; Kavitha Shree, G.G.; Bharathi, A.; Senthil Kumar, M.; Rajiv, P. An Extensive Investigation of Combined Freeze-Drying Technologies for Fruit Conservation. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Han, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Ye, Z.; Li, P.; Gu, Q. Research Progress on Improving the Freeze-Drying Resistance of Probiotics: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, N.; Sarıtaş, S.; Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M.; Karav, S. The Impact of Freeze Drying on Bioactivity and Physical Properties of Food Products. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Barragán-Iglesias, J.; López-Ortíz, A. Strawberry Fluidized Bed Drying. Antiadhesion Pretreatments and Their Effect on Bioactive Compounds. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setareh, M.; Assari, M.R.; Basirat Tabrizi, H.; Maghamian Zadeh, A. Experimental and Drying Kinetics Study on Millet Particles by a Pulsating Fluidized Bed Dryer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, K.; Sadaka, S.S. Challenges and Opportunities Associated with Drying Rough Rice in Fluidized Bed Dryers: A Review. Trans. ASABE 2020, 63, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Langrish, T.A.G. A Review of the Treatments to Reduce Anti-Nutritional Factors and Fluidized Bed Drying of Pulses. Foods 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addio, S.M.; Chan, J.G.Y.; Kwok, P.C.L.; Benson, B.R.; Prud’Homme, R.K.; Chan, H.K. Aerosol Delivery of Nanoparticles in Uniform Mannitol Carriers Formulated by Ultrasonic Spray Freeze Drying. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 2891–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanning, S.; Süverkrüp, R.; Lamprecht, A. Jet-Vortex Spray Freeze Drying for the Production of Inhalable Lyophilisate Powders. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 96, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almakayeel, N.; Velu Kaliyannan, G.; Gunasekaran, R. Enhancing Power Conversion Efficiency of Polycrystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Cells Using Yttrium Oxide Anti-Reflective Coating via Electro-Spraying Method. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 42392–42403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Hao, J.; Shen, D.; Gao, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lu, B. Electro-Spraying/Spinning: A Novel Battery Manufacturing Technology. Green. Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, A. Sustainable Solar Drying: Recent Advances in Materials, Innovative Designs, Mathematical Modeling, and Energy Storage Solutions. Energy 2024, 308, 132725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. A Review on Solar Drying of Agricultural Produce. J. Food Process. Technol. 2016, 7, 1000623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, A. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Solar Drying of Sewage Sludge in Poland. Czas. Tech. 2017, 12, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kherrafi, M.A.; Benseddik, A.; Saim, R.; Bouregueba, A.; Badji, A.; Nettari, C.; Hasrane, I. Advancements in Solar Drying Technologies: Design Variations, Hybrid Systems, Storage Materials and Numerical Analysis: A Review. Sol. Energy 2024, 270, 112383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jittanit, W.; Angkaew, K. Effect of Superheated-Steam Drying Compared to Conventional Parboiling on Chalkiness, Head Rice Yield and Quality of Chalky Rice Kernels. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020, 87, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckhahn, A.; Srzednicki, G.; Desai, D.K. Drying of Beef in Superheated Steam. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, F.; Yi, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, Y. Superheated Steam Technology: Recent Developments and Applications in Food Industries. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Han, P.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, D. Superheated Steam Drying and Torrefaction of Wet Biomass: The Effect on Products Characteristics. Fuel 2025, 388, 134441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yang, P.; Sun, P.; Ren, L.; Bu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D. Effects of Superheated Steam Processing Conditions on the Drying Behavior of Potatoes and Functional Properties of Potato Powder. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2025, 18, 9746–9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obajemihi, O.I.; Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, D.-W. Novel Sequential and Simultaneous Infrared-Accelerated Drying Technologies for the Food Industry: Principles, Applications and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1465–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundzadeh Yamchi, A.; Hosainpour, A.; Hassanpour, A.; Rezvanivand Fanaei, A. Developing Ultrasound-Assisted Infrared Drying Technology for Bitter Melon (Momordica charantia). J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jin, X.; Han, Y.; Zhai, S.; Zhang, K.; Jia, W.; Chen, J. Infrared Drying Effects on the Quality of Jujube and Process Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. LWT 2024, 214, 117089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansu, Ü. Utilization of Infrared Drying as Alternative to Spray- and Freeze-Drying for Low Energy Consumption in the Production of Powdered Gelatin. Gels 2024, 10, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravallika, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Singhal, R.S. Supercritical Drying of Food Products: An Insightful Review. J. Food Eng. 2023, 343, 111375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, A.; Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Dye Removal from Wastewater Using Nanostructured Chitosan Aerogels Produced by Supercritical CO2 Drying. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 216, 106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demina, T.S.; Minaev, N.V.; Akopova, T.A. Polysaccharide-Based Aerogels Fabricated via Supercritical Fluid Drying: A Systematic Review. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 13331–13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.T.; Li, T.H.; Tsai, H.M.; Chien, L.J.; Chuang, Y.H. Formulation of Inhalable Beclomethasone Dipropionate-Mannitol Composite Particles through Low-Temperature Supercritical Assisted Atomization. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 168, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.D.; Goñi, M.L.; Gañán, N.A. Effect of Supercritical CO2 Drying Variables and Gel Composition on the Textural Properties of Cellulose Aerogels. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 215, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.L.; Johnston, K.P.; Williams, R.O., III. Solution-Based Particle Formation of Pharmaceutical Powders by Supercritical or Compressed Fluid CO2 and Cryogenic Spray-Freezing Technologies. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2001, 27, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.E. Pharmaceutical Spray Drying: Solid-Dose Process Technology Platform for the 21st Century. Ther. Deliv. 2012, 3, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.S.; Lohare, G.B.; Bari, M.M.; Chavan, R.B.; Barhate, S.D.; Shah, C.B. Spray Drying in Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Res. J. Pharm. Dos. Forms Technol. 2012, 4, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sollohub, K.; Cal, K. Spray Drying Technique: II. Current Applications in Pharmaceutical Technology. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Patel, J.; Chakraborty, S. Review of Patents and Application of Spray Drying in Pharmaceutical, Food and Flavor Industry. Recent. Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2014, 8, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aundhia, C.J.; Raval, J.A.; Patel, M.M.; Shah, N.V.; Chauhan, S.P.; Sailor, G.U.; Javia, A.R. Spray Drying in the Pharmaceutical Industry—A Review. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 2, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B. Influence of Composition and Spray-Drying Process Parameters on Carrier-Free DPI Properties and Behaviors in the Lung: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ré, M.-I. Formulating Drug Delivery Systems by Spray Drying. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, J.M.; Adam, M.S.; Wood, J.D. Engineering Advances in Spray Drying for Pharmaceuticals. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2021, 12, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaitone, B.; Al-Zahrani, A. Modeling Drying Behavior of an Aqueous Chitosan Single Droplet Using the Reaction Engineering Approach. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyar, H.; Schalau, G. Recent Developments in Silicones for Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2015, 6, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, M.J.; Roberts, C.J.; Davies, M.C.; James, M.B. A Nanoscale Study of Particle Friction in a Pharmaceutical System. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 325, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh-Hashjin, A.; Monajjemzadeh, F.; Ghafourian, T.; Hamishehkar, H.; Nokhodchi, A. Compatibility Study of Formoterol Fumarate-Lactose Dry Powder Inhalation Formulations: Spray Drying, Physical Mixture and Commercial DPIs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 95, 105538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varun, N.; Dutta, A.; Ghoroi, C. Influence of Surface Interaction between Drug and Excipient in Binary Mixture for Dry Powder Inhaler Applications. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.H.; Chan, H.K.; Price, R. A Critical View on Lactose-Based Drug Formulation and Device Studies for Dry Powder Inhalation: Which Are Relevant and What Interactions to Expect? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, X.; Chan, L.W.; Steckel, H.; Heng, P.W.S. Physico-Chemical Aspects of Lactose for Inhalation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, T.; Najafian, S.; Patel, K.; Lacombe, J.; Chaudhuri, B. Optimization of Carrier-Based Dry Powder Inhaler Performance: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Nainwal, N. The Influence of Carrier Type, Physical Characteristics, and Blending Techniques on the Performance of Dry Powder Inhalers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 76, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.M.; Xu, Z.; Hickey, A.J. Dry Powder Aerosols Generated by Standardized Entrainment Tubes from Alternative Sugar Blends: 3. Trehalose Dihydrate and d-Mannitol Carriers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 3430–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Ballesteros, D.; Charan, C.; Stults, C.L.M.; Stevenson, C.L.; Miller, D.P.; Vehring, R.; Tep, V.; Kuo, M. Trileucine Improves Aerosol Performance and Stability of Spray-Dried Powders for Inhalation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, S.; Parumasivam, T.; Denman, J.A.; Gengenbach, T.; Tang, P.; Mao, S.; Chan, H.-K. L-Leucine as an Excipient against Moisture on in Vitro Aerosolization Performances of Highly Hygroscopic Spray-Dried Powders. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 102, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littringer, E.M.; Mescher, A.; Schroettner, H.; Achelis, L.; Walzel, P.; Urbanetz, N.A. Spray Dried Mannitol Carrier Particles with Tailored Surface Properties—The Influence of Carrier Surface Roughness and Shape. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 82, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Manta, K.; Kostantini, C.; Kikionis, S.; Banella, S.; Ioannou, E.; Christodoulou, E.; Rekkas, D.M.; Dallas, P.; Vertzoni, M.; et al. Nasal Powders of Quercetin-β-Cyclodextrin Derivatives Complexes with Mannitol/Lecithin Microparticles for Nose-to-Brain Delivery: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 121016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.T.; Yen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Nghiem, T.H.L.; Pham, H.T.; Raal, A.; Heinämäki, J.; Pham, T.M.H. Berberine-Loaded Liposomes for Oral Delivery: Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization and in-Vivo Evaluation in an Endogenous Hyperlipidemic Animal Model. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 616, 121525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Dong, Y.; Ng, W.K.; Pastorin, G. Preparation of Drug Nanocrystals Embedded in Mannitol Microcrystals via Liquid Antisolvent Precipitation Followed by Immediate (on-Line) Spray Drying. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, P. Transdermal Codelivery System of Resveratrol Nanocrystals and Fluorouracil@ HP-β-CD by Dissolving Microneedles for Cutaneous Melanoma Treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 91, 105257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Friess, W. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics Lipid-Coated Mannitol Core Microparticles for Sustained Release of Protein Placebo IgG Loaded Placebo. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 128, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoe, T.; Ozeki, T.; Okada, H. Preparation of Drug Nanoparticle-Containing Microparticles Using a 4-Fluid Nozzle Spray Drier for Oral, Pulmonary, and Injection Dosage Forms. J. Control. Release 2007, 122, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codrons, V.; Vanderbist, F.; Verbeeck, R.K.; Arras, M.; Lison, D.; Préat, V.; Vanbever, R. Systemic Delivery of Parathyroid Hormone (1-34) Using Inhalation Dry Powders in Rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungaro, F.; D’Angelo, I.; Miro, A.; La Rotonda, M.I.; Quaglia, F. Engineered PLGA Nano- and Micro-Carriers for Pulmonary Delivery: Challenges and Promises. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Lin, S.; Niu, B.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Influence of Physical Properties of Carrier on the Performance of Dry Powder Inhalers. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaialy, W.; Ticehurst, M.; Nokhodchi, A. Dry Powder Inhalers: Mechanistic Evaluation of Lactose Formulations Containing Salbutamol Sulphate. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 423, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, V.; Lee, W.-H.; Loo, C.-Y.; Haghi, M.; Young, P.M.; Scalia, S.; Traini, D. In Vitro Biological Activity of Resveratrol Using a Novel Inhalable Resveratrol Spray-Dried Formulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 491, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikwade, S.R.; Bajaj, A.N.; Gurav, P.; Gatne, M.M.; Singh Soni, P. Development of Budesonide Microparticles Using Spray-Drying Technology for Pulmonary Administration: Design, Characterization, In Vitro Evaluation, and In Vivo Efficacy Study. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boeck, K.; Haarman, E.; Hull, J.; Lands, L.C.; Moeller, A.; Munck, A.; Riethmüller, J.; Tiddens, H.; Volpi, S.; Leadbetter, J.; et al. Inhaled Dry Powder Mannitol in Children with Cystic Fibrosis: A Randomised Efficacy and Safety Trial. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilton, D.; Robinson, P.; Cooper, P.; Gallagher, C.G.; Kolbe, J.; Fox, H.; Jaques, A.; Charlton, B. Inhaled Dry Powder Mannitol in Cystic Fibrosis: An Efficacy and Safety Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, I.; Ünal, G.; Yilmaz, A.I.; Güney, A.Y.; Durduran, Y.; Pekcan, S. Inhaled Dry Powder Mannitol Treatment in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: Evaluation of Clinical Data in a Real-World Setting. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2022, 35, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marante, T.; Viegas, C.; Duarte, I.; Macedo, A.S.; Fonte, P. An Overview on Spray-Drying of Protein-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles for Dry Powder Inhalation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.D.; Daviskas, E.; Brannan, J.D.; Chan, H.K. Repurposing Excipients as Active Inhalation Agents: The Mannitol Story. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 133, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönckedieck, M.; Kamplade, J.; Fakner, P.; Urbanetz, N.A.; Walzel, P.; Steckel, H.; Scherließ, R. Dry Powder Inhaler Performance of Spray Dried Mannitol with Tailored Surface Morphologies as Carrier and Salbutamol Sulphate. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 524, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torge, A.; Grützmacher, P.; Mücklich, F.; Schneider, M. The Influence of Mannitol on Morphology and Disintegration of Spray-Dried Nano-Embedded Microparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 104, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Wen, B.; Yang, T.; Liu, K.; Qin, M.; Ding, D. The Characteristics of Novel Quercetin Loaded Chitosan/Mannitol/Leucine Microspheres Prepared by Spray Drying for Inhalation. J. Control. Release 2017, 259, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har, C.L.; Fu, N.; Chan, E.S.; Tey, B.T.; Chen, X.D. In Situ Crystallization Kinetics and Behavior of Mannitol during Droplet Drying. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, K.; Alfagih, I.M.; Ali, R.; Elsayed, M.M.A. Inhalable Microparticles Containing Terbinafine for Management of Pulmonary Fungal Infections: Spray Drying Process Engineering Using Lactose vs. Mannitol as Excipients. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, L.; Wan, F.; Rantanen, J.; Cun, D.; Yang, M. Effect of Thermal and Shear Stresses in the Spray Drying Process on the Stability of SiRNA Dry Powders. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 566, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, K.; Ali, R.; Alheibshy, F.; Almutairi, T.J.; Alshammari, R.F.; Alhajj, N.; Arpagaus, C.; Elsayed, M.M.A. Particle Engineering by Nano Spray Drying: Optimization of Process Parameters with Hydroethanolic versus Aqueous Solutions. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdynand, M.S.; Nokhodchi, A. Co-Spraying of Carriers (Mannitol-Lactose) as a Method to Improve Aerosolization Performance of Salbutamol Sulfate Dry Powder Inhaler. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z.; Heng, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y. Specific Surface Area of Mannitol Rather than Particle Size Dominant the Dissolution Rate of Poorly Water-Soluble Drug Tablets: A Study of Binary Mixture. Int J Pharm 2024, 660, 124280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, K.; Kwok, P.C.L.; Fukushige, K.; Prud’Homme, R.K.; Chan, H.K. Enhanced Dissolution of Inhalable Cyclosporine Nano-Matrix Particles with Mannitol as Matrix Former. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosquillon, C.; Rouxhet, P.G.; Ahimou, F.; Simon, D.; Culot, C.; Préat, V.; Vanbever, R. Aerosolization Properties, Surface Composition and Physical State of Spray-Dried Protein Powders. J. Control. Release 2004, 99, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Hoag, S.W. The Impact of Diluents on the Compaction, Dissolution, and Physical Stability of Amorphous Solid Dispersion Tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 654, 123924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arte, K.S.; Tower, C.W.; Mutukuri, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Patel, S.M.; Munson, E.J.; Zhou, Q.T. Understanding the Impact of Mannitol on Physical Stability and Aerosolization of Spray-Dried Protein Powders for Inhalation. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 650, 123698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaee, A.; Albadarin, A.B.; Padrela, L.; Femmer, T.; O’Reilly, E.; Walker, G. Spray Drying of Pharmaceuticals and Biopharmaceuticals: Critical Parameters and Experimental Process Optimization Approaches. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 127, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbiciński, I.; Li, X. Conditions for Accurate CFD Modeling of Spray-Drying Process. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordón, M.G.; Alasino, N.P.X.; Camacho, N.M.; Millán-Rodríguez, F.; Pedroche-Jiménez, J.J.; Villanueva-Lazo, Á.; Ribotta, P.D.; Martínez, M.L. Mathematical Modeling of the Spray Drying Processes at Laboratory and Pilot Scales for the Development of Functional Microparticles Loaded with Chia Oil. Powder Technol. 2023, 430, 119018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focaroli, S.; Mah, P.T.; Hastedt, J.E.; Gitlin, I.; Oscarson, S.; Fahy, J.V.; Healy, A.M. A Design of Experiment (DoE) Approach to Optimise Spray Drying Process Conditions for the Production of Trehalose/Leucine Formulations with Application in Pulmonary Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 562, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanojia, G.; Willems, G.-J.; Frijlink, H.W.; Kersten, G.F.A.; Soema, P.C.; Amorij, J.-P. A Design of Experiment Approach to Predict Product and Process Parameters for a Spray Dried Influenza Vaccine. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 511, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, S.; Swain, S.; Rahman, M.; Hasnain, M.S.; Imam, S.S. Chapter 3—Application of Design of Experiments (DoE). In Pharmaceutical Quality by Design: Principles and Applications; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 43–64. ISBN 9780128157992. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, I.; Myint, M.; Nguyen-khuong, T.; Ho, Y.S.; Kong, S.; Lakshmanan, M.; Walsh, I.; Myint, M.; Nguyen-khuong, T.; Ho, Y.S. Harnessing the Potential of Machine Learning for Advancing “ Quality by Design “ in Biomanufacturing. MAbs 2022, 14, 2013593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaria, B.; Kumar, P. Optimization of Spray Drying Parameters for Beetroot Juice Powder Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.N.R.; Katari, O.; Pawde, D.M.; Boddeda, G.S.B.; Goswami, A.; Mutheneni, S.R.; Shunmugaperumal, T. Application of Design of Experiments® Approach-Driven Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Systematic Optimization of Reverse Phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography Method to Analyze Simultaneously Two Drugs (Cyclosporin A and Etodolac) in Solution, Human Plasma, Nanocapsules, and Emulsions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssefi, S.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Mousavi, S.M. Comparison of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) in the Prediction of Quality Parameters of Spray-Dried Pomegranate Juice. Dry. Technol. 2009, 27, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariwala, N.; Putta, C.L.; Gatade, K.; Umarji, M.; Nazrin, S.; Rahman, R.; Pawde, D.M.; Sree, A.; Kamble, A.S.; Goswami, A.; et al. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology Intriguing of Pharmaceutical Product Development Processes with the Help of Artificial Intelligence and Deep/Machine Learning or Artificial Neural Network. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, H.; Heidarpour, A.; Shayan, A.; Nguyen, V.P. A Robust Time-Dependent Model of Alkali-Silica Reaction at Different Temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 106, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, G.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qi, J. Advances and Challenges of the Spray Drying Technology: Towards Accurately Constructing Inorganic Multi-Functional Materials and Related Applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannigan, P.; Bao, Z.; Hickman, R.J.; Aldeghi, M.; Häse, F.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Allen, C. Machine Learning Models to Accelerate the Design of Polymeric Long-Acting Injectables. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleilat, L.; Feltner, L.; Stumpf, D.; Mort, P. Mapping Process-Product Relations by Ensemble Regression—A Granulation Case Study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 317, 122042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Malvandi, A.; Feng, H.; Shao, C. Uncertainty-Aware Constrained Optimization for Air Convective Drying of Thin Apple Slices Using Machine-Learning-Based Response Surface Methodology. J. Food Eng. 2025, 394, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzel, P. Influence of the Spray Method on Product Quality and Morphology in Spray Drying. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2011, 34, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obón, J.M.; Luna-Abad, J.P.; Bermejo, B.; Fernández-López, J.A. Thermographic Studies of Cocurrent and Mixed Flow Spray Drying of Heat Sensitive Bioactive Compounds. J. Food Eng. 2020, 268, 109745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boel, E.; Koekoekx, R.; Dedroog, S.; Babkin, I.; Vetrano, M.R.; Clasen, C.; Van den Mooter, G. Unraveling Particle Formation: From Single Droplet Drying to Spray Drying and Electrospraying. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Barba, F.; Wang, J.; Picano, F. Revisiting D2-Law for the Evaporation of Dilute Droplets. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 51701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M. A New Approach to Modelling of Single Droplet Drying. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaitone, B. Evaporation of Oblate Spheroidal Droplets: A Theoretical Analysis. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2018, 205, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Al Zaitone, B.; Tropea, C. Evaporation of Pure Liquid Droplets: Comparison of Droplet Evaporation in an Acoustic Field versus Glass-Filament. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 3914–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhericher, M.; Levy, A.; Borde, I. Theoretical Models of Single Droplet Drying Kinetics: A Review. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobry, D.E.; Settell, D.M.; Baumann, J.M.; Ray, R.J.; Graham, L.J.; Beyerinck, R.A. A Model-Based Methodology for Spray-Drying Process Development. J. Pharm. Innov. 2009, 4, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.J.; Chen, X.D.; Pearce, D. On the Mechanisms of Surface Formation and the Surface Compositions of Industrial Milk Powders. Dry. Technol. 2003, 21, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, D.H.S.; Birchal, V.S.; Costa Junior, E.F. Particle Morphology and Shrinkage in Spray Dryers: A Review Focused on Modeling Single Droplet Drying. Dry. Technol. 2024, 42, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, L.; Buffo, A.; Vanni, M.; Frungieri, G. Micromechanics and Strength of Agglomerates Produced by Spray Drying. JCIS Open 2023, 9, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, N.; Yahya, M.F.Z.R.; O’Reilly, N.J.; Cathcart, H. Development and Characterization of a Spray-Dried Inhalable Ternary Combination for the Treatment of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Infection in Cystic Fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 192, 106654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, Z.; Fu, J. Particle Morphomics by High-Throughput Dynamic Image Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.S.; Pijpers, I.A.B.; Ridolfo, R.; van Hest, J.C.M. Controlling the Morphology of Copolymeric Vectors for next Generation Nanomedicine. J. Control. Release 2017, 259, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Cui, Z.; He, G.; Huang, L.; Chen, M. Phosphorus Adsorption onto Clay Minerals and Iron Oxide with Consideration of Heterogeneous Particle Morphology. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaitone, B.; Al-Zahrani, A. Spray Drying of Cellulose Nanofibers: Drying Kinetics Modeling of a Single Droplet and Particle Formation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2021, 44, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehring, R. Pharmaceutical Particle Engineering via Spray Drying. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.A.; Dunbar, C.A. Bioengineering of Therapeutic Aerosols. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002, 4, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, A.H.L.; Tong, H.H.Y.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Shekunov, B. Particle Engineering for Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2007, 24, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maa, Y.-F.; Henry R., C.; Phuong-Anh, N.; Hsu, C.C. The Effect of Operating and Formulation Variables on the Morphology of Spray-Dried Protein Particles. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 1997, 2, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.M.; Baumann, J.M.; Morgen, M.M. Predicting Spray Dried Dispersion Particle Size Via Machine Learning Regression Methods. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 3223–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.V.M.; Anantatamukala, A.; Dahotre, N.B. Deep Learning Based Automated Quantification of Powders Used in Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 11, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz López, C.A.; Peeters, K.; Van Impe, J. Data-Driven Modeling of the Spray Drying Process. Process Monitoring and Prediction of the Particle Size in Pharmaceutical Production. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25678–25693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, S.; Urfi, S.M.; Kusumastuti, A.; Baskoro, W.W. Analysis of Inlet Temperature and Airflow Rate on Drying Process in a Spray Dryer Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Method. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2022, 1, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrish, T.; Chiou, D. Producing Powders of Hibiscus Extract in a Laboratory-Scale Spray Dryer. Int. J. Food Eng. 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, G. Abiad, O.H.C.; Carvajal, M.T. Effect of Spray Drying Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties and Enthalpy Relaxation of α-Lactose. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1303–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littringer, E.M.; Noisternig, M.F.; Mescher, A.; Schroettner, H.; Walzel, P.; Griesser, U.J.; Urbanetz, N.A. The Morphology and Various Densities of Spray Dried Mannitol. Powder Technol. 2013, 246, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zier, K.-I.; Wulf, S.; Leopold, C.S. Factors Influencing the Properties and the Stability of Spray-Dried Sennae Fructus Extracts. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, E.M.; Boom, R.M.; Schutyser, M.A.I. Particle Morphology and Powder Properties during Spray Drying of Maltodextrin and Whey Protein Mixtures. Powder Technol. 2020, 363, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littringer, E.M.; Mescher, A.; Eckhard, S.; Schröttner, H.; Langes, C.; Fries, M.; Griesser, U.; Walzel, P.; Urbanetz, N.A. Spray Drying of Mannitol as a Drug Carrier—The Impact of Process Parameters on Product Properties. Dry. Technol. 2012, 30, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, D.G.; Langrish, T.A.G.; Braham, R. The Effect of Temperature on the Crystallinity of Lactose Powders Produced by Spray Drying. J. Food Eng. 2008, 86, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.B.J.; Chua, X.; Ang, C.; Subramanian, G.S.; Tan, S.Y.; Lin, E.M.J.; Wu, W.Y.; Goh, K.K.T.; Lim, K. Effects of Spray-Drying Inlet Temperature on the Production of High-Quality Native Rice Starch. Processes 2021, 9, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Van den Mooter, G. Spray Drying Formulation of Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 100, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, D.; Salehi, A.; Niakousari, M. Determination of Physical Properties of Sour Orange Juice Powder Produced by a Spray Dryer. In Proceedings of the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers Annual International Meeting 2012, Dallas, TX, USA, 29 July–1 August 2012; Volume 5, pp. 4240–4253. [Google Scholar]

- Kathiman, M.N.; Abdul Mudalip, S.K.; Gimbun, J. Effect of Feed Flowrates on the Physical Properties and Antioxidant of Mahkota Dewa (Phaleria macrocarpa) Encapsulated Powder. IIUM Eng. J. 2022, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.G.; Schaldach, G.; Littringer, E.M.; Mescher, A.; Griesser, U.J.; Braun, D.E.; Walzel, P.E.; Urbanetz, N.A. The Impact of Spray Drying Outlet Temperature on the Particle Morphology of Mannitol. Powder Technol. 2011, 213, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrish, T.A.G. Assessing the Rate of Solid-Phase Crystallization for Lactose: The Effect of the Difference between Material and Glass-Transition Temperatures. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandharamakrishnan, C.; Rielly, C.D.; Stapley, A.G.F. Effects of Process Variables on the Denaturation of Whey Proteins during Spray Drying. Dry. Technol. 2007, 25, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhong, Q. LWT—Food Science and Technology Effects of Media, Heat Adaptation, and Outlet Temperature on the Survival of Lactobacillus Salivarius NRRL B-30514 after Spray Drying and Subsequent Storage. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littringer, E.M.; Paus, R.; Mescher, A.; Schroettner, H.; Walzel, P.; Urbanetz, N.A. The Morphology of Spray Dried Mannitol Particles—The Vital Importance of Droplet Size. Powder Technol. 2013, 239, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Influence of Process Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties of Açai (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) Powder Produced by Spray Drying. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickovic, D.; Czaja, T.P.; Gaiani, C.; Pedersen, S.J.; Ahrné, L.; Hougaard, A.B. The Effect of Feed Formulation on Surface Composition of Powders and Wall Deposition during Spray Drying of Acidified Dairy Products. Powder Technol. 2023, 418, 118297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goula, A.M.; Adamopoulos, K.G. Spray Drying of Tomato Pulp: Effect of Feed Concentration. Dry. Technol. 2004, 22, 2309–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.H.; Mata, M.E.R.M.C.; Fortes, M.; Duarte, M.E.M.; Pasquali, M.; Lisboa, H.M. Influence of Spray Drying Conditions on the Properties of Whole Goat Milk. Dry. Technol. 2020, 39, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.W.; Ibrahim, M.N.; Kamil, R.; Taip, F.S. Empirical Modeling for Spray Drying Process of Sticky and Non-Sticky Products. Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczap, J.P.; Jacobs, I.C. Atomization and Spray Drying Processes. In Microencapsulation in the Food Industry: A Practical Implementation Guide; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 59–71. ISBN 9780128216835. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, C.; Casimiro, T.; Costa, E.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A. Optimization of Supercritical CO2-Assisted Spray Drying Technology for the Production of Inhalable Composite Particles Using Quality-by-Design Principles. Powder Technol. 2019, 357, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.U.; Langrish, T.A.G. The Effect of Different Atomizing Gases and Drying Media on the Crystallization Behavior of Spray-Dried Powders. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicher, M.T.; Schwaminger, S.P.; von der Haar-Leistl, D.; Fellenberg, E.; Berensmeier, S. Process Development for Pilot-Scale Spray Drying of Ultrasmall Iron (Oxyhydr)Oxide Nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 2024, 433, 119186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClair, D.A.; Cranston, E.D.; Xing, Z.; Thompson, M.R. Optimization of Spray Drying Conditions for Yield, Particle Size and Biological Activity of Thermally Stable Viral Vectors. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 2763–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Chávez, J.; Padhi, S.S.P.; Hartge, U.; Heinrich, S.; Smirnova, I. Optimization of the Spray-Drying Process for Developing Aquasolv Lignin Particles Using Response Surface Methodology. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 2348–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, A.; Lalitha, K.G.; Ruckmani, K.; Khutle, N.; Pawar, H.; Dand, N.; Vijaya, C. ICH Q8 Guidelines in Practice: Spray Drying Process Optimization by 23 Factorial Design for the Production of Famotidine Nanoparticles. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2014, 2, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, V.; Pandey, E.; Pandya, T.; Shah, P.; Patel, A.; Trivedi, R.; Gohel, M.; Baldaniya, L.; Gandhi, T. Formulation of Dry Powder Inhaler of Anti-Tuberculous Drugs Using Spray Drying Technique and Optimization Using 23 Level Factorial Design Approach. Curr. Drug Ther. 2019, 14, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.; Sinha, S.; Harfoot, R.; Quiñones-Mateu, M.E.; Das, S.C. Manipulation of Spray-Drying Conditions to Develop an Inhalable Ivermectin Dry Powder. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.; Marchant, D.; Wheatley, M.A. Optimization of Spray Drying by Factorial Design for Production of Hollow Microspheres for Ultrasound Imaging. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 56, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, T.F.; Lanchote, A.D.; Da Costa, J.S.; Viçosa, A.L.; De Freitas, L.A.P. A Multivariate Approach Applied to Quality on Particle Engineering of Spray-Dried Mannitol. Adv. Powder Technol. 2015, 26, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjasirimongkol, P.; Piriyaprasarth, S.; Sriamornsak, P. Effect of Formulations and Spray Drying Process Conditions on Physical Properties of Resveratrol Spray-Dried Emulsions. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 819, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Gajera, B.; Pinninti, A.; Mohammed, I.A.; Dave, R.H. Strategizing Spray Drying Process Optimization for the Manufacture of Redispersible Indomethacin Nanoparticles Using Quality-by-Design Principles. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, J.; Pavloková, S.; Hořavová, H.; Gajdziok, J. Optimization of Spray Drying Process Parameters for the Preparation of Inhalable Mannitol-Based Microparticles Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramek-Romanowska, K.; Odziomek, M.; Sosnowski, T.R.; Gradoń, L. Effects of Process Variables on the Properties of Spray-Dried Mannitol and Mannitol/Disodium Cromoglycate Powders Suitable for Drug Delivery by Inhalation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 13922–13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, M.I.; Tajber, L.; Corrigan, O.I.; Healy, A.M. Optimisation of Spray Drying Process Conditions for Sugar Nanoporous Microparticles (NPMPs) Intended for Inhalation. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 421, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anish, C.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Sehgal, D.; Panda, A.K. Influences of Process and Formulation Parameters on Powder Flow Properties and Immunogenicity of Spray Dried Polymer Particles Entrapping Recombinant Pneumococcal Surface Protein A. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 466, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboo, S.; Tumban, E.; Peabody, J.; Wafula, D.; Peabody, D.S.; Chackerian, B.; Muttil, P. Optimized Formulation of a Thermostable Spray-Dried Virus-Like Particle Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Shrestha, N.; van de Streek, J.; Mu, H.; Yang, M. Spray Drying of Fenofibrate Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouteu, P.A.N.; Kemegne, A.G.; Pahane, M.M.; Fanta, A.S.Y.; Membangmi, A.K.; Tchamaleu, D.V.T.; Agbor, G.A.; Mouangue, M.R. Face-Centered Central Composite Design for the Optimization of the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Kernels and Shells of Raphia Farinifera and Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J. Food Process Preserv. 2024, 2024, 8849005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, A.; Broekhuis, J.; Grasmeijer, N.; Tonnis, W.; Ketolainen, J.; Frijlink, H.W.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Efficient Production of Solid Dispersions by Spray Drying Solutions of High Solid Content Using a 3-Fluid Nozzle. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 123, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvarsson, P.T.; Schmidt, S.T.; Christensen, D.; Larsen, N.B.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Andersen, P.; Rantanen, J.; Nielsen, H.M.; Yang, M.; Foged, C. Designing CAF-Adjuvanted Dry Powder Vaccines: Spray Drying Preserves the Adjuvant Activity of CAF01. J. Control. Release 2013, 167, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, D.M.K.; Cun, D.; Maltesen, M.J.; Frokjaer, S.; Nielsen, H.M.; Foged, C. Spray Drying of SiRNA-Containing PLGA Nanoparticles Intended for Inhalation. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handscomb, C.S.; Kraft, M.; Bayly, A.E. A New Model for the Drying of Droplets Containing Suspended Solids. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaitone, B.; Lamprecht, A. Single Droplet Drying Step Characterization in Microsphere Preparation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 105, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuts, P.S.; Strumillo, C.; Zbicinski, I. Evaporation Kinetics of Single Droplets Containing Dissolved Bioaiass. Dry. Technol. 1996, 14, 2041–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhericher, M.; Levy, A.; Borde, I. Theoretical Drying Model of Single Droplets Containing Insoluble or Dissolved Solids. Dry. Technol. 2007, 25, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.D.; Bayly, A.E.; Johns, M.L. Magnetic Resonance Studies of Detergent Drop Drying. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 3449–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, J.V.; Jaskulski, M.; Kharaghani, A. Modeling of Maltodextrin Drying Kinetics for Use in Simulations of Spray Drying. Dry. Technol. 2025, 43, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, K.; Tan, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z. CFD Modeling of Baijiu Yeast Spray Drying Process and Improved Design of Drying Tower. Dry. Technol. 2024, 42, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafori, H.; Karimian, H. CFD Simulation of Milk Performance Parameters Effect on the Physical Indices of a Spray Dryer. Innov. Food Technol. 2025, 12, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Putranto, A. Reaction Engineering Approach (REA) to Modeling Drying Problems: Recent Development and Implementations. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaitone, B.; Al-Zahrani, A.; Ahmed, O.; Saeed, U.; Taimoor, A.A. Spray Drying of PEG6000 Suspension: Reaction Engineering Approach (REA) Modeling of Single Droplet Drying Kinetics. Processes 2022, 10, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Lin, S.X.Q. Air Drying of Milk Droplet under Constant and Time-dependent Conditions. Aiche J. 2005, 51, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, R.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Applications in Spray Drying of Food Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbun, J.; Law, W.P.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling of the Dairy Drying Processes. In Handbook of Drying for Dairy Products; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 179–201. ISBN 9781118930526. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Mujumdar, A.S. Numerical Study of Two-Stage Horizontal Spray Dryers Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaleddine, T.J.; Ray, M.B. Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics for Simulation of Drying Processes: A Review. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 120–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchal, V.S.; Huang, L.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Passos, M.L. Spray Dryers: Modeling and Simulation. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kurichi, K.; Mujumdar, A.S. A Parametric Study of the Gas Flow Patterns and Drying Performance of Co-Current Spray Dryer: Results of a Computational Fluid Dynamics Study. Dry. Technol. 2003, 21, 957–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindang, A.; Panggabean, S.; Wulandari, F. CFD Analysis of Temperature Drying Chamber at Rotary Dryer With Combined Energy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1155, 12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kurichi, K.; Mujumdar, A.S. Simulation of a Spray Dryer Fitted with a Rotary Disk Atomizer Using a Three-Dimensional Computional Fluid Dynamic Model. Dry. Technol. 2004, 22, 1489–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekjani, N.; Jafari, S.M. Simulation of Food Drying Processes by Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD); Recent Advances and Approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanipour, S.; Sokhansanj, A.; Jafari, N.; Hamishehkar, H.; Saha, S.C. Engineering Nanoliposomal Tiotropium Bromide Embedded in a Lactose-Arginine Carrier Forming Trojan-Particle Dry Powders for Efficient Pulmonary Drug Delivery: A Combined Approach of in Vitro-3D Printing and in Silico-CFD Modeling. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 671, 125171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coimbra, J.C.; Lopes, L.C.; da Silva Cotrim, W.; Prata, D.M. CFD Modeling of Spray Drying of Fresh Whey: Influence of Inlet Air Temperature on Drying, Fluid Dynamics, and Performance Indicators. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qomariyah, L.; Rahmana Putra, N.; Shamsuddin, R.; Hirano, T.; Ratna Puri, N.; Alawiyah, L.; Hamzah, A.; Sabar, S. Insights into Nanostructured Silica Particle Formation from Sodium Silicate Using Spray Drying: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Chem. Phys. 2024, 585, 112347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Han, F.; Wen, G.; Tang, P.; Hou, Z. Mathematical Model and Numerical Investigation of the Influence of Spray Drying Parameters on Granule Sizes of Mold Powder. Particuology 2024, 85, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldo Benavides-Morán, A.C.; Gómez, A. Spray Drying Experiments and CFD Simulation of Guava Juice Formulation. Dry. Technol. 2021, 39, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qomariyah, L.; Puri, N.R.; Grady, E.; Nurtono, T.; Widiyastuti; Kusdianto; Madhania, S.; Winardi, S. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Modelling of ZnO-SiO2 Composite Through a Consecutive Electrospray and Spray Drying Method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2344, 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerotholi, L.; Everson, R.C.; Hattingh, B.B.; Koech, L.; Le Roux, I.; Neomagus, H.W.J.P.; Rutto, H. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling and Analysis of Lime Slurry Drying in a Laboratory Spray Dry Scrubber. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 21038–21061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longest, P.W.; Farkas, D.; Hassan, A.; Hindle, M. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Simulations of Spray Drying: Linking Drying Parameters with Experimental Aerosolization Performance. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nualnuk, P.; Sukpancharoen, S.; Srinophakun, T.R. Coupled Eulerian-Lagrangian Simulation of Spray-Drying Skimmed Milk Powder. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2024, 58, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajishima, T.; Taira, K. Computational Fluid Dynamics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-45302-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskulski, M.; Wawrzyniak, P.; Zbiciński, I. CFD Simulations of Droplet and Particle Agglomeration in an Industrial Counter-Current Spray Dryer. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandharamakrishnan, C. Computational Fluid Dynamics Applications in Food Processing. In Computational Fluid Dynamics Applications in Food Processing; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-1-4614-7990-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ducept, F.; Sionneau, M.; Vasseur, J. Superheated Steam Dryer: Simulations and Experiments on Product Drying. Chem. Eng. J. 2002, 86, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, M.; Haus, J.; Pietsch-Braune, S.; Kleine Jäger, F.; Heinrich, S. CFD-Aided Population Balance Modeling of a Spray Drying Process. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhericher, M.; Levy, A.; Borde, I. Modelling of Particle Breakage during Drying. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2008, 47, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Ranade, V.; Shardt, O.; Matsoukas, T. Challenges and Opportunities Concerning Numerical Solutions for Population Balances: A Critical Review. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2022, 55, 383002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X. Single Image Super-Resolution Using Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2022, 163, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, E.T.; Nasir, A.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Muhammadu, M.M.; Musa, N.A.; Tijani, J.O.; Bada, S.O. Nano-Coolants for Thermal Enhancement in Heat Exchangers: A Review of Prospects, Challenges and Applications. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 8, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, V.; Singh, P.; Thakur, V.K.; Abdelkader, T.K.; Yadav, A.S. Advancements in Computational Tools for Indirect Solar Drying Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskiran, C.; Riglin, J.; Schleicher, W.; Oztekin, A. Transient Analysis of Micro-Hydrokinetic Turbines for River Applications. Ocean Eng. 2017, 129, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A. Free Stream Turbulence Intensity Effects on the Flow over a Circular Cylinder at Re = 3900: Bifurcation, Attractors and Lyapunov Metric. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Katsuchi, H.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Bao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y. Strategy for Mitigating Wake Interference Between Offshore Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines: Evaluation of Vertically Staggered Arrangement. Appl. Energy 2023, 351, 121850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Roldán, N.I.; López-Ortiz, A.; Ituna-Yudonago, J.F.; Nair, P.K.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Martynenko, A. A Current Review: Engineering Design of Greenhouse Solar Dryers Exploring Novel Approaches. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 73, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Tian, H.; Yuan, X.; Liu, S.; Peng, Q.; Shi, Y.; Jin, L.; Ye, L.; Jia, J.; Ying, D.; et al. CFD-Assisted Modeling of the Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactors for Wastewater Treatment—A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskulski, M.; Wawrzyniak, P. Simulation and Design of Spray Driers. In Spray Drying for the Food Industry: Unit Operations and Processing Equipment in the Food Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 29–56. ISBN 9780128197998. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, D.V.E.; Santos, A.L.G.; dos Santos, E.D.; Souza, J.A. Overtopping Device Numerical Study: Openfoam Solution Verification and Evaluation of Curved Ramps Performances. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 131, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Nicholls, W.; Stickland, M.T.; Dempster, W.M. CFD Study of Jet Impingement Test Erosion Using Ansys Fluent® and OpenFOAM®. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2015, 197, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windt, C.; Davidson, J.; Ringwood, J. V High-Fidelity Numerical Modelling of Ocean Wave Energy Systems: A Review of Computational Fluid Dynamics-Based Numerical Wave Tanks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuanyou, L. An Investigation of Error Sources in Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling of a Co-Current Spray Dryer. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2004, 12, 756–761. [Google Scholar]

- Jubaer, H.; Afshar, S.; Xiao, J.; Chen, X.D.; Selomulya, C.; Woo, M.W. On the Importance of Droplet Shrinkage in CFD-Modeling of Spray Drying. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1785–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.S.; Huang, L.-X.; Chen, X.D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Spray-Drying. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2010, 90, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Jaskulski, M.; Piatkowski, M.; Tsotsas, E. CFD Simulation of Agglomeration and Coalescence in Spray Dryer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 247, 117064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubaer, H. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling of Agglomeration during Spray Drying. Ph.D. Thesis, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Mahmud, T.; Heggs, P.; Ghadiri, M.; Bayly, A.; Crosby, M.; Ahmadian, H.; Martindejuan, L.; Alam, Z. Residence Time Distribution of Glass Ballotini in Isothermal Swirling Flows in a Counter-Current Spray Drying Tower. Powder Technol. 2017, 305, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefidan, A.M.; Sellier, M.; Hewett, J.N.; Abdollahi, A.; Willmott, G.R.; Becker, S.M. Numerical Model to Study the Statistics of Whole Milk Spray Drying. Powder Technol. 2022, 411, 117923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breinlinger, T.; Hashibon, A.; Kraft, T. Simulation of the Influence of Surface Tension on Granule Morphology during Spray Drying Using a Simple Capillary Force Model. Powder Technol. 2015, 283, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloss, C.; Goniva, C.; Hager, A.; Amberger, S.; Pirker, S. Models, Algorithms and Validation for Opensource DEM and CFD-DEM. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2012, 12, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, M.; Weis, D.; Togni, R.; Goniva, C.; Heinrich, S. Describing the Drying and Solidification Behavior of Single Suspension Droplets Using a Novel Unresolved CFD-DEM Simulation Approach. Processes 2024, 12, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhericher, M.; Levy, A.; Borde, I. Multi-Scale Multiphase Modeling of Transport Phenomena in Spray-Drying Processes. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, W.D.; Chen, X.D. Multiscale Modeling for Nanoscale Surface Composition of Spray-Dried Powders: The Effect of Initial Droplet Size. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sper de Almeida, E. Reducing Time Delays in Computing Numerical Weather Models at Regional and Local Levels: A Grid-Based Approach. Int. J. Grid Comput. Appl. 2012, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.E.; Paluch, A.S.; Andrés Gutiérrez Suárez, J.; Humberto, C.; Urueña, G.; Mejía, A.G. Adaptive Mesh Refinement Strategies for Cost-Effective Eddy-Resolving Transient Simulations of Spray Dryers. ChemEngineering 2023, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, P.; Kumar, S.S.; Pathipati, C. A Review of Machine Learning Strategies for Enhancing Efficiency and Innovation in Real-World Engineering Applications. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, R.H.; Revathi, A.; Ramana, K.; Raut, R.; Dhanaraj, R.K. A Review on Machine Learning Strategies for Real-World Engineering Applications. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 1833507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T. Machine Learning for Structural Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review. Structures 2022, 38, 448–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhang, K.; Bagheri, M.; Burken, J.G.; Gu, A.; Li, B.; Ma, X.; Marrone, B.L.; Ren, Z.J.; Schrier, J.; et al. Machine Learning: New Ideas and Tools in Environmental Science and Engineering. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12741–12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınar, Z.M.; Abdussalam Nuhu, A.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O.; Asmael, M.; Safaei, B. Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance towards Sustainable Smart Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Noack, B.R.; Koumoutsakos, P. Machine Learning for Fluid Mechanics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2020, 52, 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.; Drikakis, D.; Charissis, V. Machine-Learning Methods for Computational Science and Engineering. Computation 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Rensi, S.E.; Torng, W.; Altman, R.B. Machine Learning in Chemoinformatics and Drug Discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.; Ihsanullah, I.; Naushad, M.; Sillanpää, M. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Water Treatment for Optimization and Automation of Adsorption Processes: Recent Advances and Prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldaregay, A.Z.; Årsand, E.; Walderhaug, S.; Albers, D.; Mamykina, L.; Botsis, T.; Hartvigsen, G. Data-Driven Modeling and Prediction of Blood Glucose Dynamics: Machine Learning Applications in Type 1 Diabetes. Artif. Intell. Med. 2019, 98, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S.; Rhoads, D.D.; Sepulveda, J.; Zang, C.; Chadburn, A.; Wang, F. Building the Model: Challenges and Considerations of Developing and Implementing Machine Learning Tools for Clinical Laboratory Medicine Practice. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2023, 147, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Casalino, L.P.; Khullar, D. Deep Learning in Medicine—Promise, Progress, and Challenges. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, C.; Hutter, F.; Hoos, H.H.; Leyton-Brown, K. Auto-WEKA: Combined Selection and Hyperparameter Optimization of Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Chicago, OH, USA, 11–14 August 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume Part F128815, pp. 847–855. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Ye, L.; Ge, Z. Laplacian Regularization of Linear Regression Model for Semi-Supervised Industrial Soft Sensor Development. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystritskaya, E.V.; Pomerantsev, A.L.; Rodionova, O.Y. Non-Linear Regression Analysis: New Approach to Traditional Implementations. J. Chemom. 2000, 14, 667–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj; Prakash, K.B.; Kanagachidambaresan, G.R. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning BT. In Programming with TensorFlow: Solution for Edge Computing Applications; Prakash, K.B., Kanagachidambaresan, G.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 105–144. ISBN 978-3-030-57077-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Support Vector Machines BT. In Encyclopedia of Machine Learning and Data Mining; Sammut, C., Webb, G.I., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1214–1220. ISBN 978-1-4899-7687-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Bajorath, J. Evolution of Support Vector Machine and Regression Modeling in Chemoinformatics and Drug Discovery. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2022, 36, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, K.; Prakash, R.B.; Balakrishnan, C.; Kumar, G.V.P.; Siva Subramanian, R.; Anita, M. Support Vector Machines: Unveiling the Power and Versatility of SVMs in Modern Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications, ICIMIA 2023, Bengaluru, India, 21–23 December 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 680–687. [Google Scholar]

- Fradi, A.; Tran, T.T.; Samir, C. Decomposed Gaussian Processes for Efficient Regression Models with Low Complexity. Entropy 2025, 27, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A. Ensemble-Trees: Leveraging Ensemble Power Inside Decision Trees. In Proceedings of the Discovery Science, Budapest, Hungary, 13–16 October 2008; Jean-Fran, J.-F., Berthold, M.R., Horváth, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.X.; Katuwal, R.; Suganthan, P.N.; Qiu, X. A Heterogeneous Ensemble of Trees. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 November–1 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, U.; Rizwan, M.; Alaraj, M.; Alsaidan, I. A Machine Learning-Based Gradient Boosting Regression Approach for Wind Power Production Forecasting: A Step towards Smart Grid Environments. Energies 2021, 14, 5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylan, O.A. Artificial Neural Network Models in Prediction of the Moisture Content of a Spray Drying Process. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2004, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrasol, M.G.M.; Suhail Hussain, S.M.; Ustun, T.S.; Sarker, M.R.; Hannan, M.A.; Mohamed, R.; Ali, J.A.; Mekhilef, S.; Milad, A. Artificial Neural Networks Based Optimization Techniques: A Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, A.S.; Kowalski, J.; Rhodes, C.T. Artificial Neural Networks: Implications for Pharmaceutical Sciences. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1995, 21, 119–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford, R. Basic Concepts of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Modeling and Its Application in Pharmaceutical Research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2000, 22, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Widrow, B.; Lehr, M.A. The Basic Ideas in Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 1994, 37, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Peng, H.H.; Yang, Z.; Ma, X.; Sahakijpijarn, S.; Moon, C.; Ouyang, D.; Williams, R.O. The Applications of Machine Learning (ML) in Designing Dry Powder for Inhalation by Using Thin-Film-Freezing Technology. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 626, 122179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Lúcio, A.; Andrade, R.; Sarinho, A.M.; Lima, J.; Batista, L.; Costa, M.E.; Nascimento, A.; Pasquali, M.B. Leveraging Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships to Design and Optimize Wall Material Formulations for Antioxidant Encapsulation via Spray Drying. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 7, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallamma, T.; Raghavendra Naveen, N.; Goudanavar, P. Spray Dried Linezolid-Loaded Inhalable Chitosan Microparticles for Tuberculosis: A QbD-Driven Approach to Enhance Pulmonary Delivery. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 3, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z. Towards Data-Driven Development of Advanced Drug Formulations Leveraging Machine Learning and Experimental Automation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Cao, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Han, D.; Meng, Z. Identifying Baicalin Concentration in Scutellaria Spray Drying Powder With Disturbed Terahertz Spectra Based on Gaussian Mixture Model. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2024, 2024, 3858763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.D.; Wildfong, P.L.D. Informatics Calibration of a Molecular Descriptors Database to Predict Solid Dispersion Potential of Small Molecule Organic Solids. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 418, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska, K.; Booth, J.; Roberts, C.J.; McCabe, J.; Dryden, I.; Fischer, P.M. Long-Term Amorphous Drug Stability Predictions Using Easily Calculated, Predicted, and Measured Parameters. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 3389–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapourani, A.; Eleftheriadou, K.; Kontogiannopoulos, K.N.; Barmpalexis, P. Evaluation of Rivaroxaban Amorphous Solid Dispersions Physical Stability via Molecular Mobility Studies and Molecular Simulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medarević, D.P.; Kachrimanis, K.; Mitrić, M.; Djuriš, J.; Djurić, Z.; Ibrić, S. Dissolution Rate Enhancement and Physicochemical Characterization of Carbamazepine-Poloxamer Solid Dispersions. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016, 21, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Agrawal, A.; Dave, R.H. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics Investigation of the Effects of Process Variables on Derived Properties of Spray Dried Solid-Dispersions Using Polymer Based Response Surface Model and Ensemble Artificial Neural Network Models. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 86, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz Castro, B.; Elbadawi, M.; Ong, J.J.; Pollard, T.; Song, Z.; Gaisford, S.; Pérez, G.; Basit, A.W.; Cabalar, P.; Goyanes, A. Machine Learning Predicts 3D Printing Performance of over 900 Drug Delivery Systems. J. Control. Release 2021, 337, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Farizhandi, K.; Alishiri, M.; Lau, R. Machine Learning Approach for Carrier Surface Design in Carrier-Based Dry Powder Inhalation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 151, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Kittikunakorn, N.; Sorman, B.; Xi, H.; Chen, A.; Marsh, M.; Mongeau, A.; Piché, N.; Williams, R.O.; Skomski, D. Application of Deep Learning Convolutional Neural Networks for Internal Tablet Defect Detection: High Accuracy, Throughput, and Adaptability. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, R.; Löbmann, K.; Strachan, C.J.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T. Emerging Trends in the Stabilization of Amorphous Drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, S.; Rades, T.; Rantanen, J.; Scherließ, R.; Cui, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Miao, P.; Xue, Q.; Liu, C.; et al. Combining Machine Learning and Molecular Simulations to Predict the Stability of Amorphous Drugs. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 159, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, B.; Jaafari, M.R.; Golabpour, A.; Momtazi-Borojeni, A.A.; Karimi, M.; Eslami, S. Application of Ensemble Machine Learning Approach to Assess the Factors Affecting Size and Polydispersity Index of Liposomal Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, D.L.; Könyves, Z.; Nagy, B.; Novák, M.; Mészáros, L.A.; Szabó, E.; Farkas, A.; Marosi, G.; Nagy, Z.K. Real-Time Release Testing of Dissolution Based on Surrogate Models Developed by Machine Learning Algorithms Using NIR Spectra, Compression Force and Particle Size Distribution as Input Data. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespi, M.; Kuhn, R.; Yen, C.W.; Leung, D. Optimization of Spray-Drying Parameters for Formulation Development at Preclinical Scale. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Patel, M.; Kulkarni, M.; Patel, M.S. DE-INTERACT: A Machine-Learning-Based Predictive Tool for the Drug-Excipient Interaction Study during Product Development—Validation through Paracetamol and Vanillin as a Case Study. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 637, 122839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xiong, H.; Ye, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, T.; Jing, Q.; Lu, J.; Pan, H.; Ren, F.; Ouyang, D. Predicting Physical Stability of Solid Dispersions by Machine Learning Techniques. J. Control. Release 2019, 311–312, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Gao, H.; Ouyang, D. PharmSD: A Novel AI-Based Computational Platform for Solid Dispersion Formulation Design. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagh, N.; Agashe, S.D. Monitoring Exhaust Air Temperature and Detecting Faults during Milk Spray Drying Using Data-Driven Framework. Dry. Technol. 2023, 41, 1991–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.F.; Silva, G.; Pinto, A.C.; Fonseca, M.; Silva, N.E.; A, B.I.F.S. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics Artificial Neural Networks Applied to Quality-by-Design: From Formulation Development to Clinical Outcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 152, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, H.; Chung, J.I.; Kiang, Y.H.; Xiao, L.Y.; Hageman, M.J. The Application of Machine Learning Algorithms in Understanding the Effect of Core/Shell Technique on Improving Powder Compactability. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 555, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletić, T.; Ibrić, S.; Đurić, Z. Combined Application of Experimental Design and Artificial Neural Networks in Modeling and Characterization of Spray Drying Drug: Cyclodextrin Complexes. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, D.; Fink, E.; Aigner, I.; Leitinger, G.; Keller, W.; Roblegg, E.; Khinast, J.G. A Multi-Step Machine Learning Approach for Accelerating QbD-Based Process Development of Protein Spray Drying. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 642, 123133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, A.; Rizzuto, F.; Rinaldi, M.; Foglio Bonda, A.; Segale, L.; Giovannelli, L. Thermodynamic Balance vs. Computational Fluid Dynamics Approach for the Outlet Temperature Estimation of a Benchtop Spray Dryer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tathawadekar, N.; Doan, N.A.K.; Silva, C.F.; Thuerey, N. Modeling of the Nonlinear Flame Response of a Bunsen-Type Flame via Multi-Layer Perceptron. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 6261–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, G.; Ju, C.; Chen, S.; Huang, W. Data-Driven Forecasting Framework for Daily Reservoir Inflow Time Series Considering the Flood Peaks Based on Multi-Head Attention Mechanism. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; George, O.A.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Woo, M.W.; Wu, W.D.; Chen, X.D. Numerical Investigation of Droplet Pre-Dispersion in a Monodisperse Droplet Spray Dryer. Particuology 2018, 38, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, V.; Duarte, D.; Fonseca, J.; Montecinos, A. Benchmarking Machine-Learning Software and Hardware for Quantitative Economics. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2020, 111, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-K.; Nurazaq, W.A.; Wang, W.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Poon, H.M.; Gan, S.; Duong, V.D.; Prapainainar, P. Unsteady Spray Dynamics of Hydro-Processed Renewable Diesel: Influence of Thermo-Physical Properties under High-Pressure Injection. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 122, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, A.; Misra, N.N. Machine Learning in Drying. Dry. Technol. 2020, 38, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, C.S.; Yerram, S.; Abishek, V.; Nizam, V.P.M.; Aglave, G.; Patnam, J.D.; Raghuvanshi, R.S.; Srivastava, S. Innovative Approaches in Regulatory Affairs: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Efficient Compliance and Decision-Making. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirakhori, F.; Niazi, S.K. Harnessing the AI/ML in Drug and Biological Products Discovery and Development: The Regulatory Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K. Regulatory Perspectives for AI/ML Implementation in Pharmaceutical GMP Environments. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantanowitz, L.; Hanna, M.; Pantanowitz, J.; Lennerz, J.; Henricks, W.H.; Shen, P.; Quinn, B.; Bennet, S.; Rashidi, H.H. Regulatory Aspects of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 37, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavasidis, I.; Lallas, E.; Leligkou, H.C.; Oikonomidis, G.; Karydas, D.; Gerogiannis, V.C.; Karageorgos, A. Deep Transformers for Computing and Predicting ALCOA+Data Integrity Compliance in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A Perspective on Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods: SHAP and LIME. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbabaie, M.; Stieglitz, S.; Frick, N.R.J. Artificial Intelligence in Disease Diagnostics: A Critical Review and Classification on the Current State of Research Guiding Future Direction. Health Technol. 2021, 11, 693–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, T.; Whitford, W. AI Applications for Multivariate Control in Drug Manufacturing. In A Handbook of Artificial Intelligence in Drug Delivery; Philip, A., Shahiwala, A., Rashid, M., Faiyazuddin, M., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 55–82. ISBN 9780323899253. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, R.B.; Helmchen, L.A. Paying for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Song, C.; Qi, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Pu, R.; Ao, Y. Visual Analysis of Drug Research and Development Based on Artificial Intelligence. J. Holist. Integr. Pharm. 2024, 5, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.L.; Guffey, M.; Jeon, B.; Vorp, D.A.; Chung, T.K. The Evolving Regulatory Landscape for Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Devices in the United States. JVS-Vasc. Insights 2025, 3, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong-Trung, N.; Born, S.; Kim, J.W.; Schermeyer, M.-T.; Paulick, K.; Borisyak, M.; Cruz-Bournazou, M.N.; Werner, T.; Scholz, R.; Schmidt-Thieme, L.; et al. When Bioprocess Engineering Meets Machine Learning: A Survey from the Perspective of Automated Bioprocess Development. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 190, 108764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Manzanares, A.; Caprolu, M.; Di Pietro, R. A Comprehensive Review on Machine Learning-Based VPN Detection: Scenarios, Methods, and Open Challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2025, 58, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Vajrashree, P.S.; Meghana, G.S.; Sastri, K.T.; Akhila, A.R.; Gowda, C.U.; Balamuralidhara , V. Beyond the Blood-Brain Barrier: Intranasal Vaccines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 216, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suffian, M.; Kuhl, U.; Bogliolo, A.; Alonso-Moral, J.M. The Role of User Feedback in Enhancing Understanding and Trust in Counterfactual Explanations for Explainable AI. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2025, 199, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]