Investigating the Mechanical Behaviour of Viscoelastic and Brittle Pharmaceutical Excipients During Tabletting: Revealing the Unobvious Potential of Advanced Compaction Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Tablet Blends and Assessment of Their Properties

2.2.1. Determination of True, Bulk and Tapped Densities

2.2.2. Characterization of Powder Flow Properties

2.3. Preparation of Tablets

2.4. Measurement of Tablet Hardness and Calculation of Tensile Strength

2.5. Characterization of the Tabletting Process

2.6. Calculation of Apparent Density, Porosity, and Solid Fraction (Out-of-Die Method)

2.7. Evaluation of Compaction Behaviour of Tablet Blends (The Compaction Triangle)

2.8. Elastic Recovery

2.9. Visualisation of Tablet Size and Shape

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Powder Properties

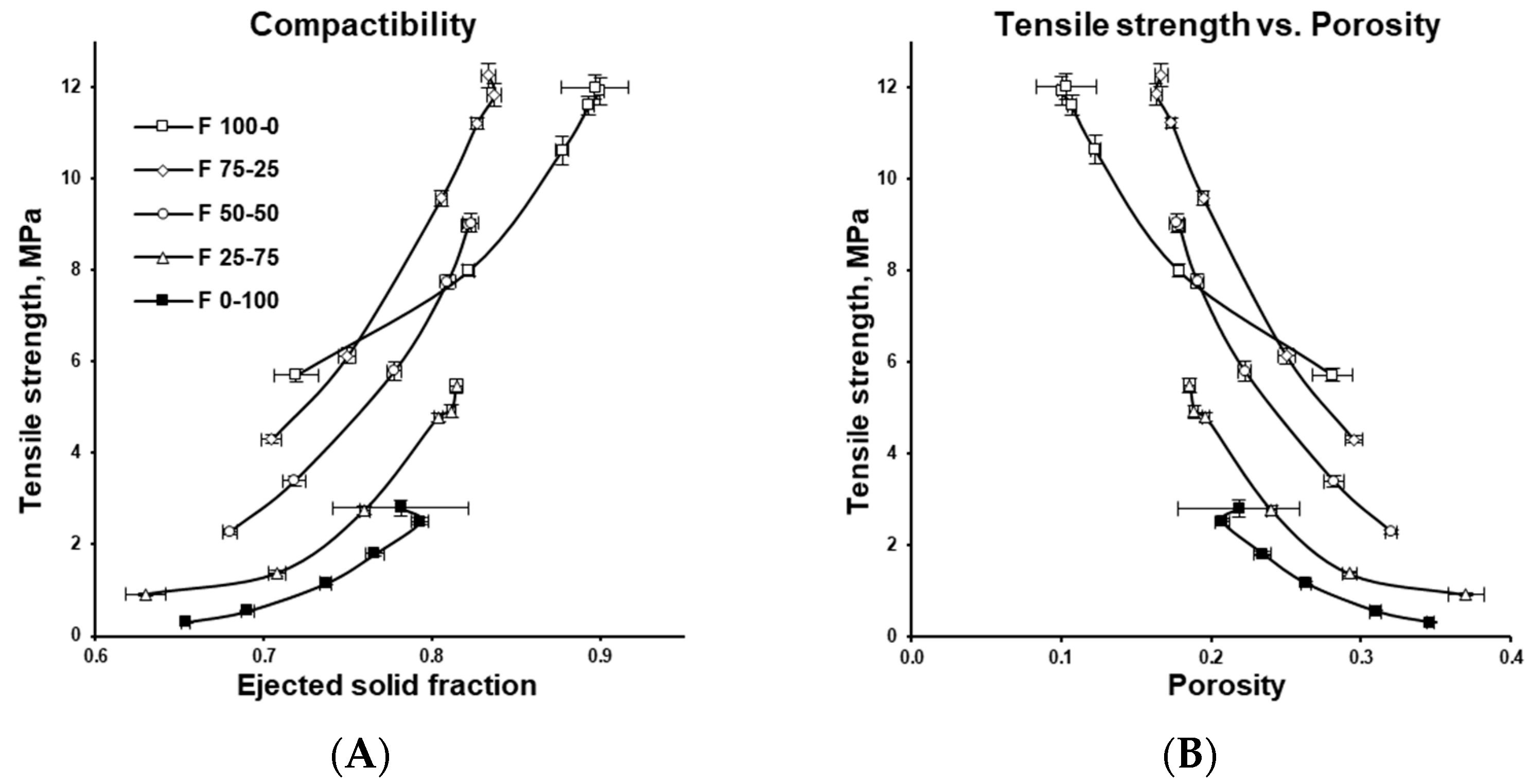

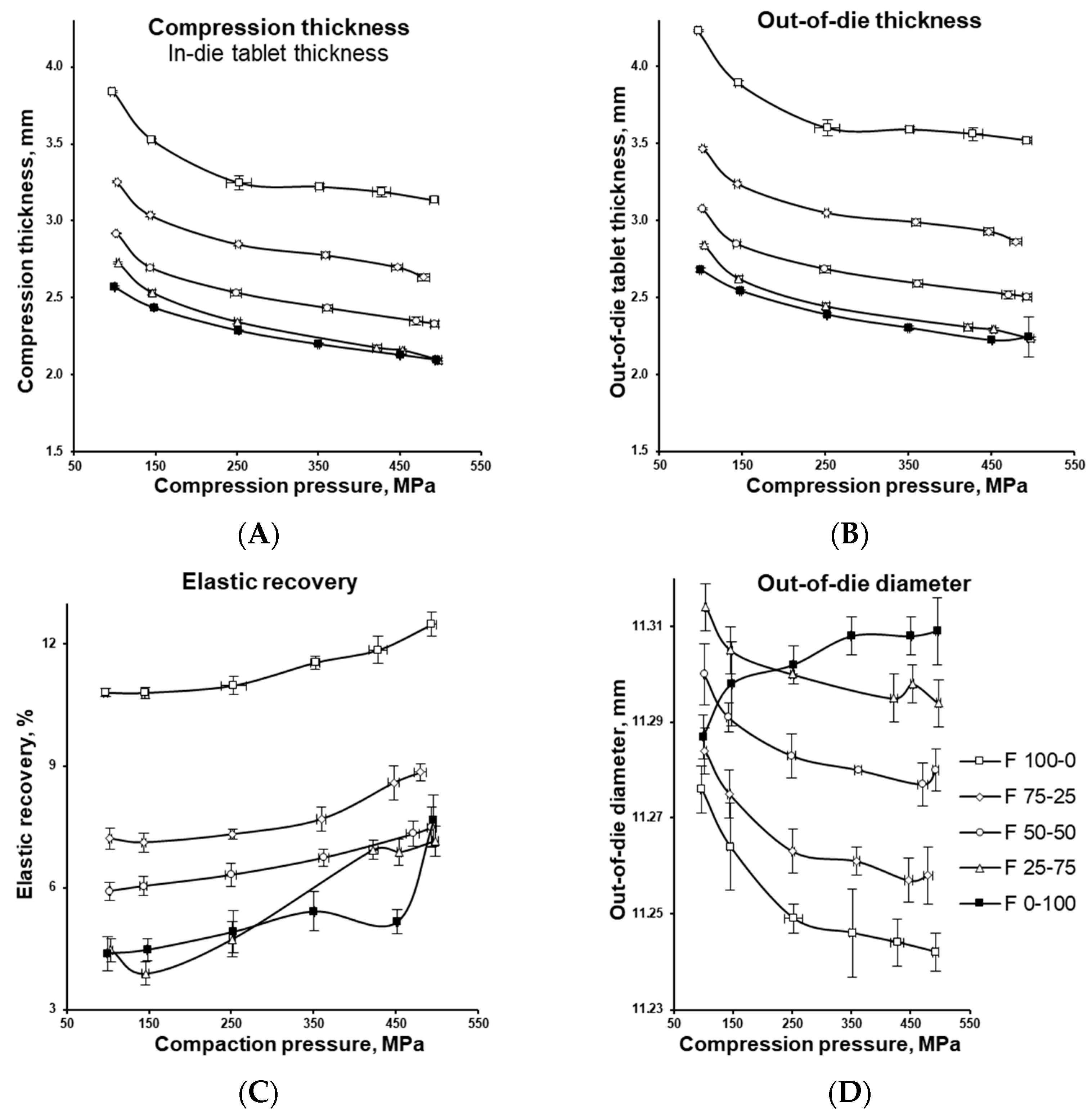

3.2. Tablet Compression Characterization

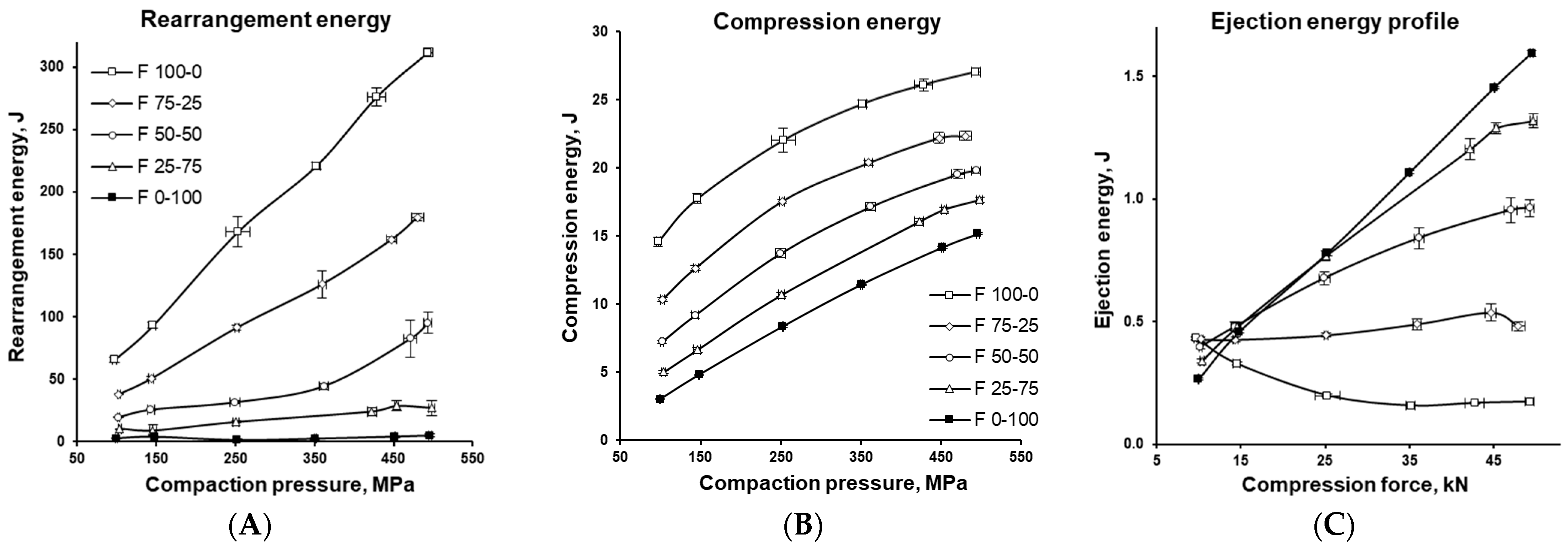

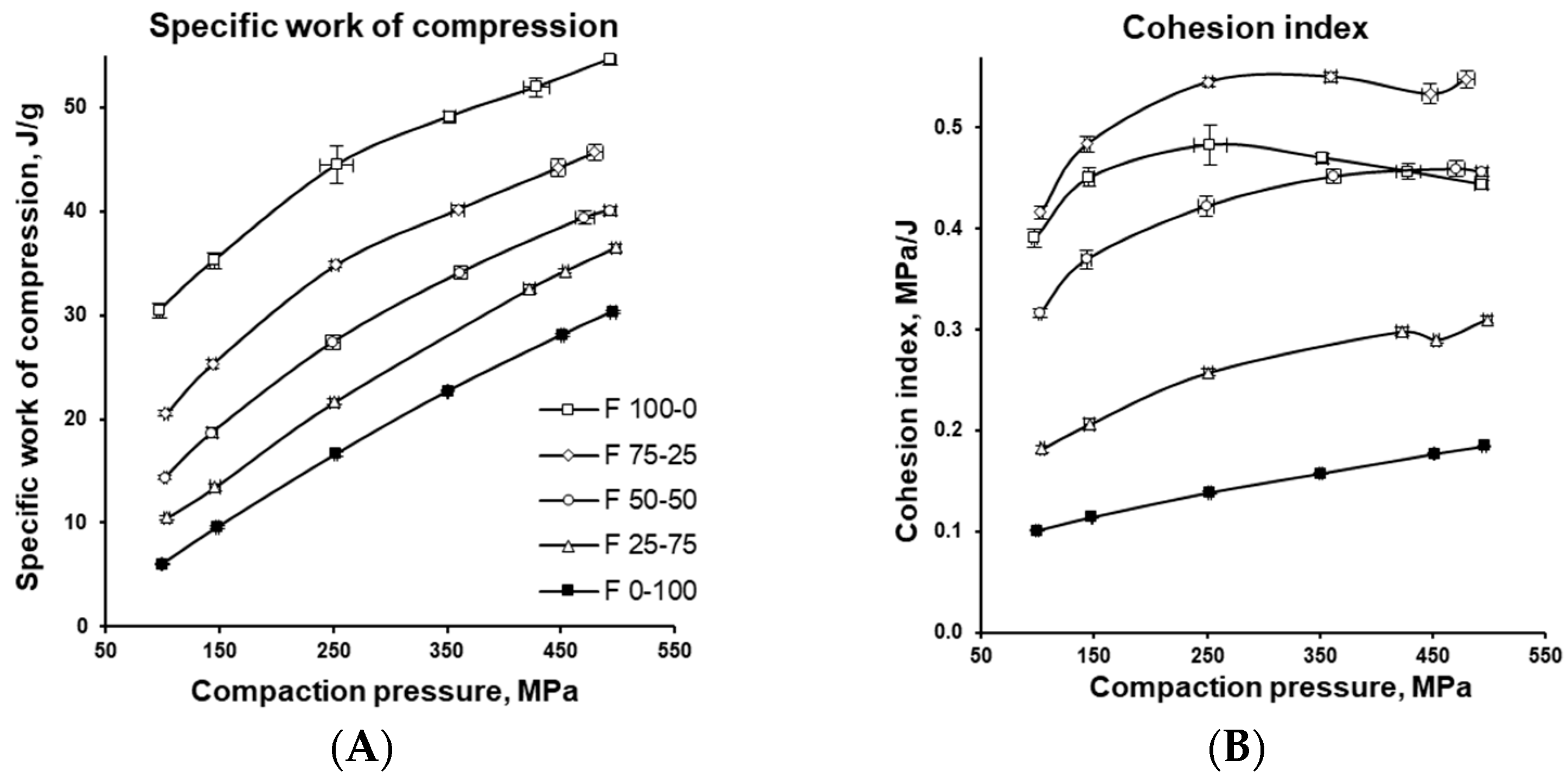

3.3. Energetic Characterization of the Tableting Process

3.4. Visualisation of the Tableting Process

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sohail Arshad, M.; Zafar, S.; Yousef, B.; Alyassin, Y.; Ali, R.; AlAsiri, A.; Chang, M.-W.; Ahmad, Z.; Elkordy, A.A.; Faheem, A.; et al. A review of emerging technologies enabling improved solid oral dosage form manufacturing and processing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, S.S.; Kshirsagar, S.J. Review on Tablet in Tablet techniques. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leane, M.; Pitt, K.; Reynolds, G. The Manufacturing Classification System (MCS) Working Group. A proposal for a drug product Manufacturing Classification System (MCS) for oral solid dosage forms. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2015, 20, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jivraj, M.; Martini, L.G.; Thomson, C.M. Thomson, An overview of the different excipients useful for the direct compression of tablets. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 2000, 3, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohylyuk, V.; Styliari, I.D.; Novykov, D.; Pikett, R.; Dattani, R. Assessment of the effect of Cellets’ particle size on the flow in a Wurster fluid-bed coater via powder rheology. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazes, R. A QbD Approach to Shorten Tablet Development Time. In Pharmaceutical Technology; MJH Life Sciences: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, A.; Serra, J.; Estevens, C.; Costa, R.; Ribeiro, A. Leveraging a multivariate approach towards enhanced development of direct compression extended release tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 646, 123432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, A.H.; Hallam, C.N.; Baker, N.A.; Murphy, D.S.; Gabbott, I.P. Understanding tablet defects in commercial manufacture and transfer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.S.; Moravkar, K.K.; Jha, D.K.; Lonkar, V.; Amin, P.D.; Chalikwar, S.S. A concise summary of powder processing methodologies for flow enhancement. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirani, A.G.; Patankar, S.P.; Borole, V.S.; Pawar, A.S.; Kadam, V.J. Direct compression high functionality excipient using coprocessing technique: A brief review. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangal, S.; Meiser, F.; Morton, D.; Larson, I. Particle Engineering of Excipients for Direct Compression: Understanding the Role of Material Properties. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 5877–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, G.K.; Rexwinkel, E.G.; Zuurman, K. Polyols as filler-binders for disintegrating tablets prepared by direct compaction. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2009, 35, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byl, E.; Lebeer, S.; Kiekens, F. Elastic recovery of filler-binders to safeguard viability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG during direct compression. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 135, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Law, Y.; Chakrabarti, S. Physical properties and compact analysis of commonly used direct compression binders. AAPS PharmSciTech 2003, 4, E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, E.; Mazel, V.; Sluga, K.K.; Nagapudi, K.; Muliadi, A.R. Beyond Brittle/Ductile Classification: Applying Proper Constitutive Mechanical Metrics to Understand the Compression Characteristics of Pharmaceutical Materials. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 1984–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagali, V.G.; Vreeman, G.; Hasabnis, A.; Sun, C.C. Predicting the tabletability of binary powder mixtures from that of individual components. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 211, 107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galichet, L.Y. Cellulose Microcrystalline. In Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients; Rowe, R.C., Sheskey, P.J., Owen, S.C., Eds.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK; American Pharmacists Association: Grayslake, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton, R.C. Calcium Phosphate Dibasic Anhydrous. In Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients; Rowe, R.C., Sheskey, P.J., Owen, S.C., Eds.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK; American Pharmacists Association: Grayslake, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ceolus™ UF: Porous MCC with Balance of Compactibility and Flowability. 2025. Available online: https://www.ceolus.com/en/mcc/grade_lineup/ceolus_uf/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Wagner, M.; Hess, T.; Zakowiecki, D. Studies on the pH-Dependent Solubility of Various Grades of Calcium Phosphate-based Pharmaceutical Excipients. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohylyuk, V.; Paulausks, A.; Radzins, O.; Lauberte, L. The Effect of Microcrystalline Cellulose–CaHPO4 Mixtures in Different Volume Ratios on the Compaction and Structural–Mechanical Properties of Tablets. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohylyuk, V. Dwell Time on Tableting: Dwell Time According to Force versus Geometric Dwell Time. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2024, 29, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulausks, A.; Kolisnyk, T.; Mohylyuk, V. The Increase in the Plasticity of Microcrystalline Cellulose Spheres’ When Loaded with a Plasticizer. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünsch, I.; Friesen, I.; Puckhaber, D.; Schlegel, T.; Finke, J.H. Scaling Tableting Processes from Compaction Simulator to Rotary Presses-Mind the Sub-Processes. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannis, K.; Schilde, C.; Finke, J.H.; Kwade, A. Modeling of High-Density Compaction of Pharmaceutical Tablets Using Multi-Contact Discrete Element Method. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, P.J. Sodium Stearyl Fumarate. In Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients; Rowe, R.C., Sheskey, P.J., Owen, S.C., Eds.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK; American Pharmacists Association: Grayslake, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, S.C. Colloidal Silicon Dioxide. In Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients; Rowe, R.C., Sheskey, P.J., Owen, S.C., Eds.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK; American Pharmacists Association: Grayslake, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mohylyuk, V.; Bandere, D. High-speed tableting of high drug-loaded tablets prepared from fluid-bed granulated isoniazid. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohylyuk, V.; Kukuls, K.; Frolova, A.J.; Horváth, Z.M.; Kolisnyk, T.; Buczkowska, E.M.; Pētersone, L.; Pelloux, A. Difference in Tableting of Lubricated Spray-Dried Mannitol and Fluid-Bed Granulated Isomalt. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuls, K.; Mohylyuk, V. Dataset: Direct Compression of Lubricated Mixture of Microcrystalline Cellulose and Calcium Phosphate Dibasic Anhydrous; Institutional Repository Dataverse; Riga Stradins University: Riga, Latvia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Newton, J. Determination of tablet strength by the diametral-compression test. J. Pharm. Sci. 1970, 59, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhondt, J.; Bertels, J.; Kumar, A.; Van Hauwermeiren, D.; Ryckaert, A.; Van Snick, B.; Klingeleers, D.; Vervaet, C.; De Beer, T. A multivariate formulation and process development platform for direct compression. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 623, 121962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backere, C.; De Beer, T.; Vervaet, C.; Vanhoorne, V. Evaluation of an external lubrication system implemented in a compaction simulator. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 587, 119675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, B.V.; Westedt, U.; Wagner, K.G. Compression Modulus and Apparent Density of Polymeric Excipients during Compression-Impact on Tabletability. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, I.; Govedarica, B.; Šibanc, R.; Dreu, R.; Srčič, S. Deformation properties of pharmaceutical excipients determined using an in-die and out-die method. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 446, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye, C.K.; Sun, C.C.; Amidon, G.E. Evaluation of the effects of tableting speed on the relationships between compaction pressure, tablet tensile strength, and tablet solid fraction. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, N.A.; Haines-Nutt, R.F. Elastic recovery and surface area changes in compacted powder systems. Powder Technol. 1974, 9, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optimizing Tablet Development: Key Characterization Parameters for Preventing Defects. 2025.07.10. TaBlitz.

- Schomberg, A.K.; Kwade, A.; Finke, J.H. Modeling die filling under gravity for different scales of rotary tablet presses. Powder Technol. 2023, 424, 118550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, K.; Ring, D.; Sheehan, L.; Foulon, A. Probabilistic analysis of weight variability in tablets & capsules arising from the filling of a cavity with powder of a poly-dispersed size. Powder Technol. 2015, 270, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, A.B.; Khan, M.A.; Gupta, A.; Faustino, P.J. Dose Uniformity of Scored and Unscored Tablets: Application of the FDA Tablet Scoring Guidance for Industry. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.C.; Himmelspach, M.W. Reduced tabletability of roller compacted granules as a result of granule size enlargement. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.C. Mechanism of moisture induced variations in true density and compaction properties of microcrystalline cellulose. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 346, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelbæk-Pedersen, A.; Vilhelmsen, T.; Wallaert, V.; Rantanen, J. Quantification of Fragmentation of Pharmaceutical Materials After Tableting. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, P.J.; Parrott, E.L. Effect of Lubricants on Tensile Strengths of Tablets. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2008, 10, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, H.; Nystrom, C. Assessing tablet bond types from structural features that affect tablet tensile strength. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, R.; Moll, K.-P.; Krumme, M.; Kleinebudde, P. How Deformation Behavior Controls Product Performance After Twin Screw Granulation With High Drug Loads and Crospovidone as Disintegrant. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborenko, N.; Shi, Z.; Corredor, C.C.; Smith-Goettler, B.M.; Zhang, L.; Hermans, A.; Neu, C.M.; Alam, A.; Cohen, M.J.; Lu, X.; et al. First-Principles and Empirical Approaches to Predicting In Vitro Dissolution for Pharmaceutical Formulation and Process Development and for Product Release Testing. AAPS J. 2019, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Sun, C.C. Gaining insight into tablet capping tendency from compaction simulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 524, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.S.; Briscoe, B.J. The elastic relaxation of starch tablets during ejection. Powder Technol. 2009, 195, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porion, P.; Busignies, V.; Mazel, V.; Leclerc, B.; Evesque, P.; Tchoreloff, P. Anisotropic porous structure of pharmaceutical compacts evaluated by PGSTE-NMR in relation to mechanical property anisotropy. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynard, J.; Amado-Becker, F.; Tchoreloff, P.; Mazel, V. Use of impulse excitation technique for the characterization of the elastic anisotropy of pharmaceutical tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 605, 120797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haware, R.V.; Tho, I.; Bauer-Brandl, A. Evaluation of a rapid approximation method for the elastic recovery of tablets. Powder Technol. 2010, 202, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiscol, R.; Finke, J.H.; Zetzener, H.; Kwade, A. Characterization of Mechanical Property Distributions on Tablet Surfaces. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizunaga, D.; Watano, S. Evaluation of Time-Dependent Deformation Behavior of Pharmaceutical Excipients in the Tableting Process. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2025, 73, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaya, A.; Aburub, A. Effect of particle size on compaction of materials with different deformation mechanisms with and without lubricants. AAPS PharmSciTech 2008, 9, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, I.M.; Arida, A.I.; Al-Tabakha, M.M. Effect of the Lubricant Magnesium Stearate on Changes of Specific Surface Area of Directly Compressible Powders under Compression. Jordan J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 8, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, K.G.; Heasley, M.G. Determination of the tensile strength of elongated tablets. Powder Technol. 2013, 238, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakowiecki, D.; Edinger, P.; Papaioannou, M.; Hess, T.; Kubiak, B.; Terlecka, A. Exploiting synergistic effects of brittle and plastic excipients in directly compressible formulations of sitagliptin phosphate and sitagliptin hydrochloride. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2022, 27, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclean, N.; Khadra, I.; Mann, J.; Williams, H.; Abbott, A.; Mead, H.; Markl, D. Investigating the role of excipients on the physical stability of directly compressed tablets. Int. J. Pharm. X 2022, 4, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overgaard, A.B.A.; Møller-Sonnergaard, J.; Christrup, L.L.; Højsted, J.; Hansen, R. Patients’ evaluation of shape, size and colour of solid dosage forms. Pharm. World Sci. 2001, 23, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, T.; Michelon, H.; Orlu, M.; Jani, Y.; Leglise, P.; Laribe-Caget, S.; Piccoli, M.; Le Fur, A.; Liu, F.; Ruiz, F.; et al. Acceptability in the Older Population: The Importance of an Appropriate Tablet Size. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient | F 100-0 | F 75-25 | F 50-50 | F 25-75 | F 0-100 | F 100-0 | F 75-25 | F 50-50 | F 25-75 | F 0-100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Ratio (% w/w) | Volume Ratio (%) | |||||||||

| MCC | 0.977 | 0.608 | 0.346 | 0.151 | 0.000 | 96.9 | 72.3 | 47.9 | 23.8 | 0.0 |

| DCPA | 0.000 | 0.369 | 0.631 | 0.826 | 0.977 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 47.9 | 71.4 | 94.6 |

| SSF | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Silica | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Total | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zakowiecki, D.; Kukuls, K.; Cal, K.; Pelloux, A.; Mohylyuk, V. Investigating the Mechanical Behaviour of Viscoelastic and Brittle Pharmaceutical Excipients During Tabletting: Revealing the Unobvious Potential of Advanced Compaction Simulation. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121606

Zakowiecki D, Kukuls K, Cal K, Pelloux A, Mohylyuk V. Investigating the Mechanical Behaviour of Viscoelastic and Brittle Pharmaceutical Excipients During Tabletting: Revealing the Unobvious Potential of Advanced Compaction Simulation. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121606

Chicago/Turabian StyleZakowiecki, Daniel, Kirils Kukuls, Krzysztof Cal, Adrien Pelloux, and Valentyn Mohylyuk. 2025. "Investigating the Mechanical Behaviour of Viscoelastic and Brittle Pharmaceutical Excipients During Tabletting: Revealing the Unobvious Potential of Advanced Compaction Simulation" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121606

APA StyleZakowiecki, D., Kukuls, K., Cal, K., Pelloux, A., & Mohylyuk, V. (2025). Investigating the Mechanical Behaviour of Viscoelastic and Brittle Pharmaceutical Excipients During Tabletting: Revealing the Unobvious Potential of Advanced Compaction Simulation. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121606