Improved Dissolution of Poorly Water-Soluble Rutin via Solid Dispersion Prepared Using a Fluid-Bed Coating System

Abstract

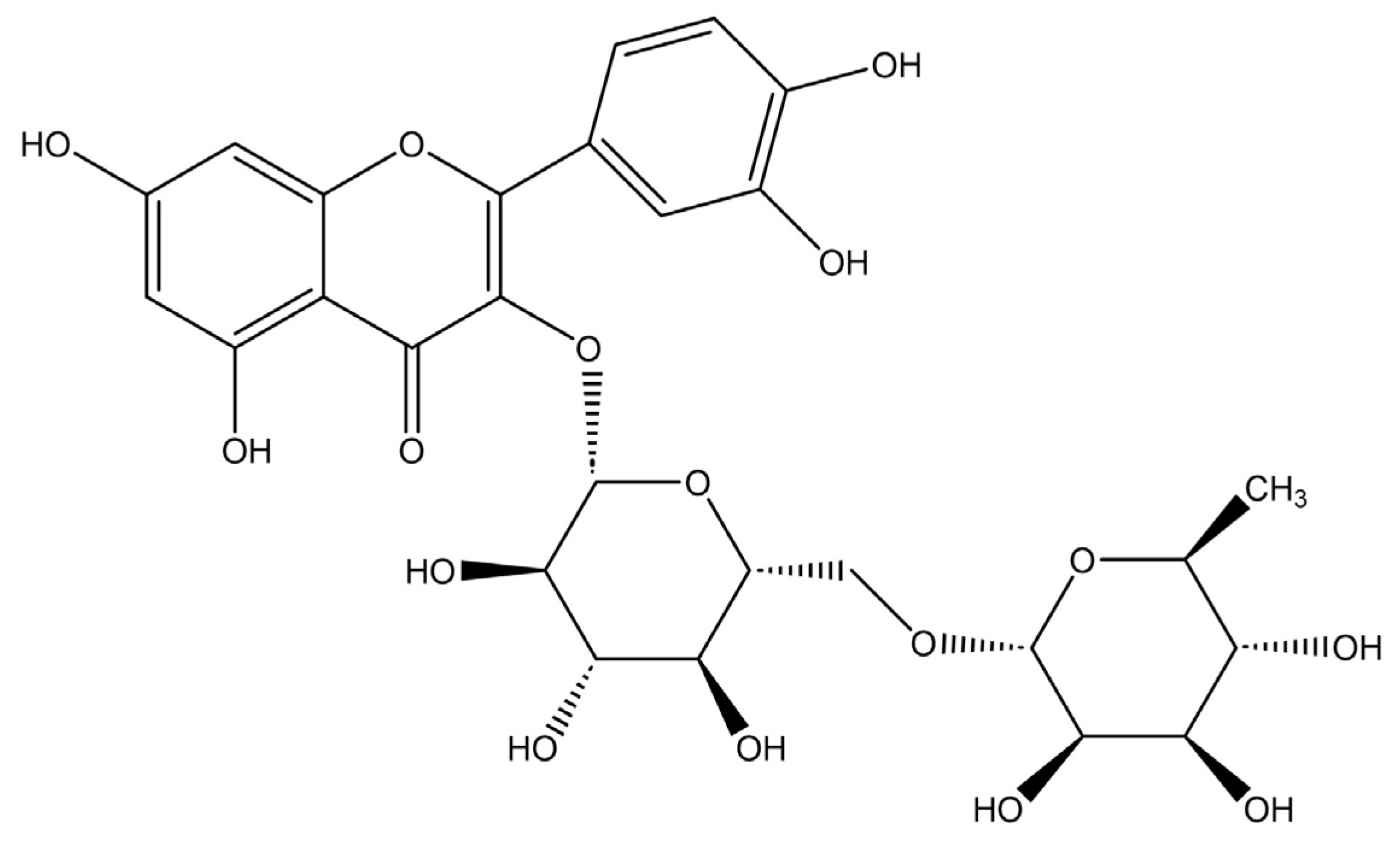

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

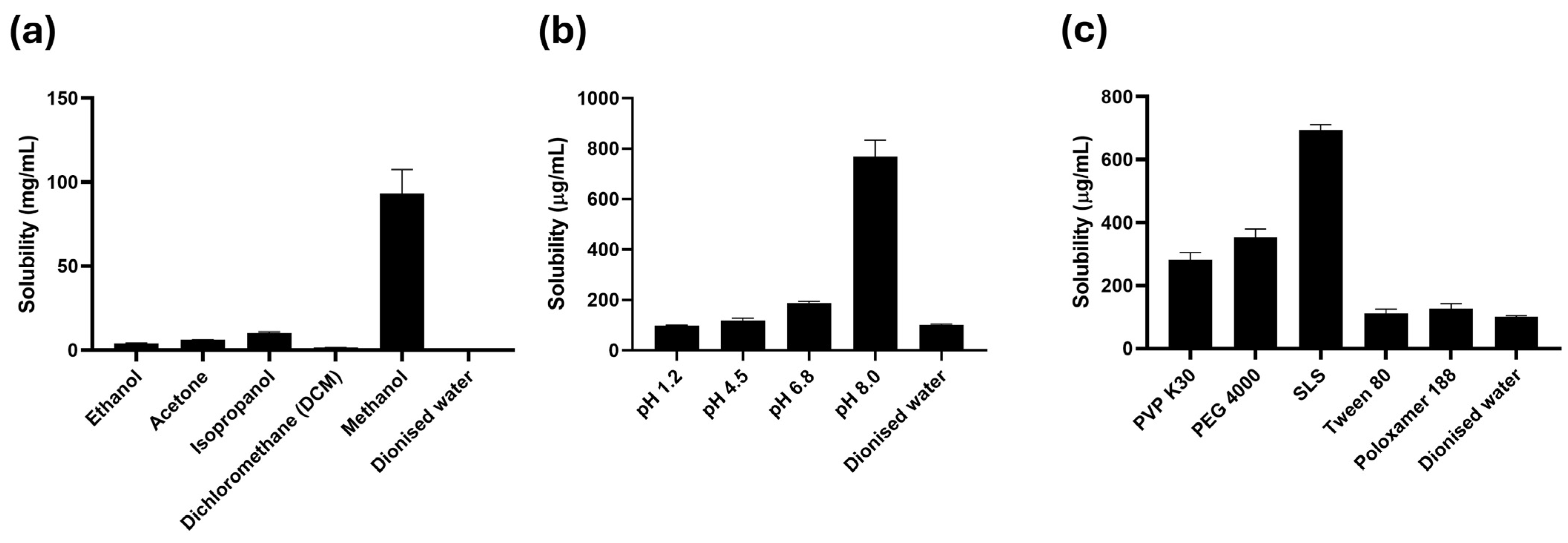

2.2. Equilibrium Solubility Studies of Rutin

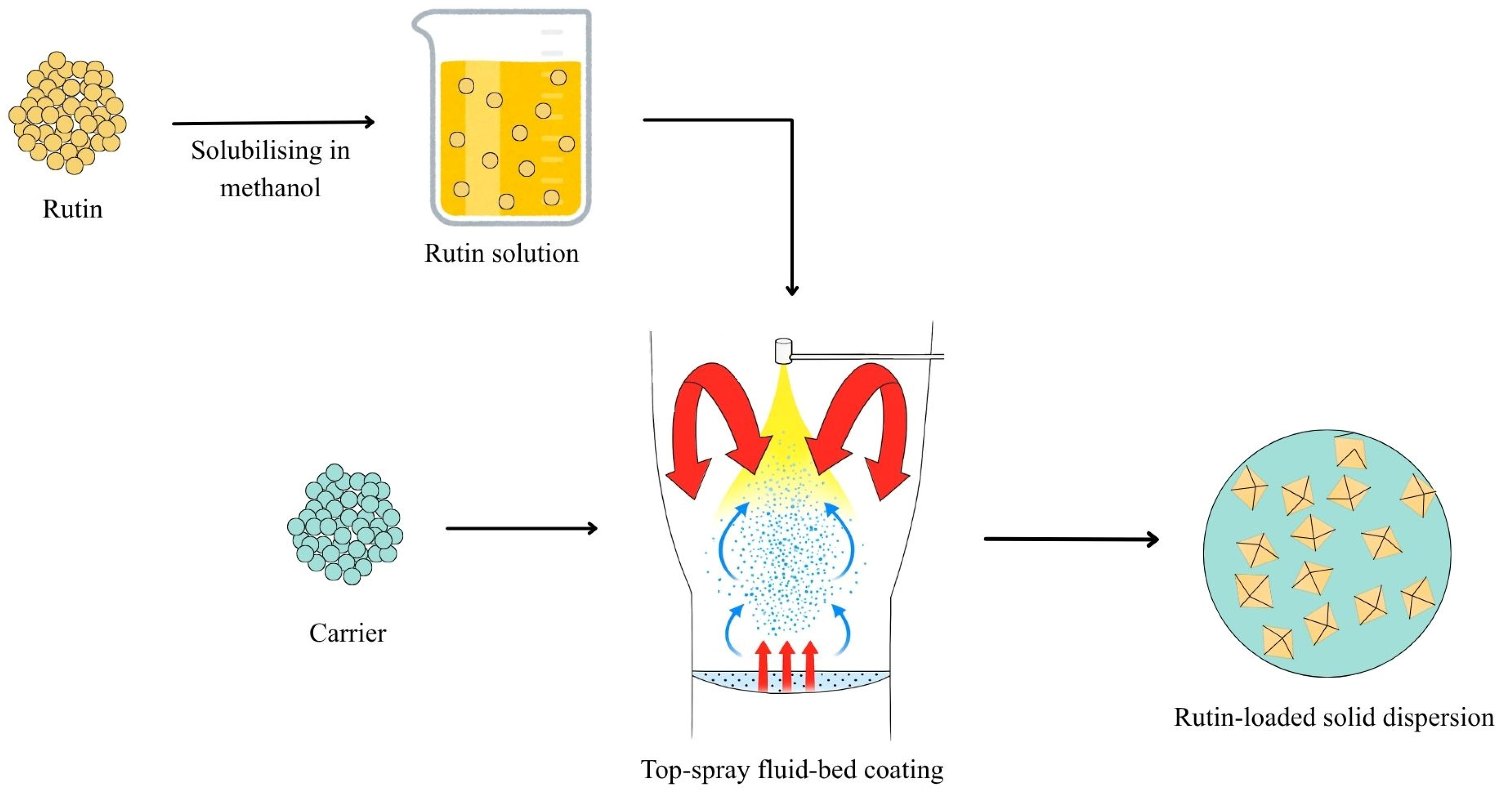

2.3. Preparation of Solid Dispersions

2.4. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD)

2.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.6. Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.8. Formulation and Preparation of Rutin-Loaded Tablets

2.9. In Vitro Dissolution Testing

2.10. Stability Studies

2.11. HPLC Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Solubility Studies of Rutin

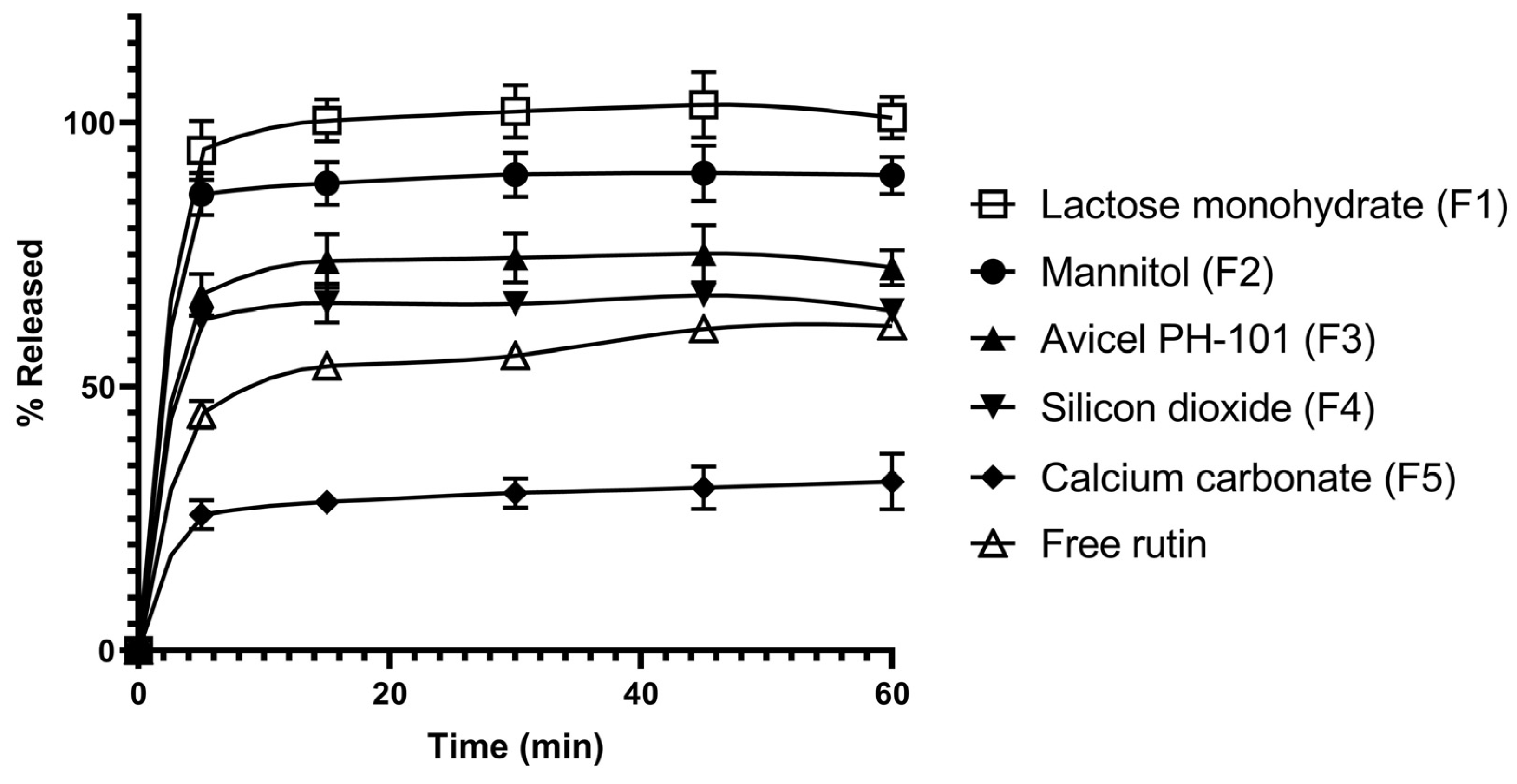

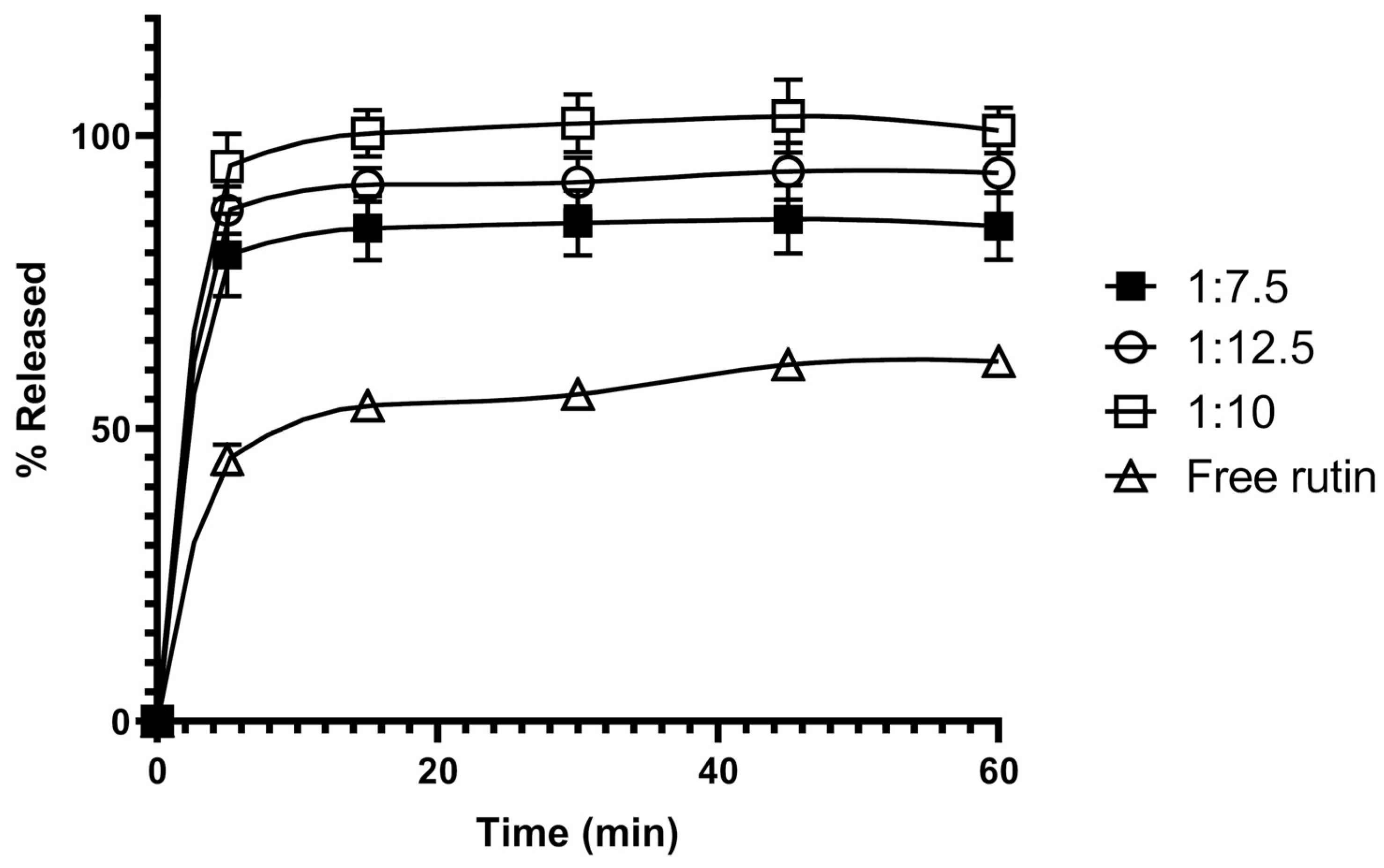

3.2. In Vitro Dissolution Studies of Rutin-Loaded Solid Dispersions

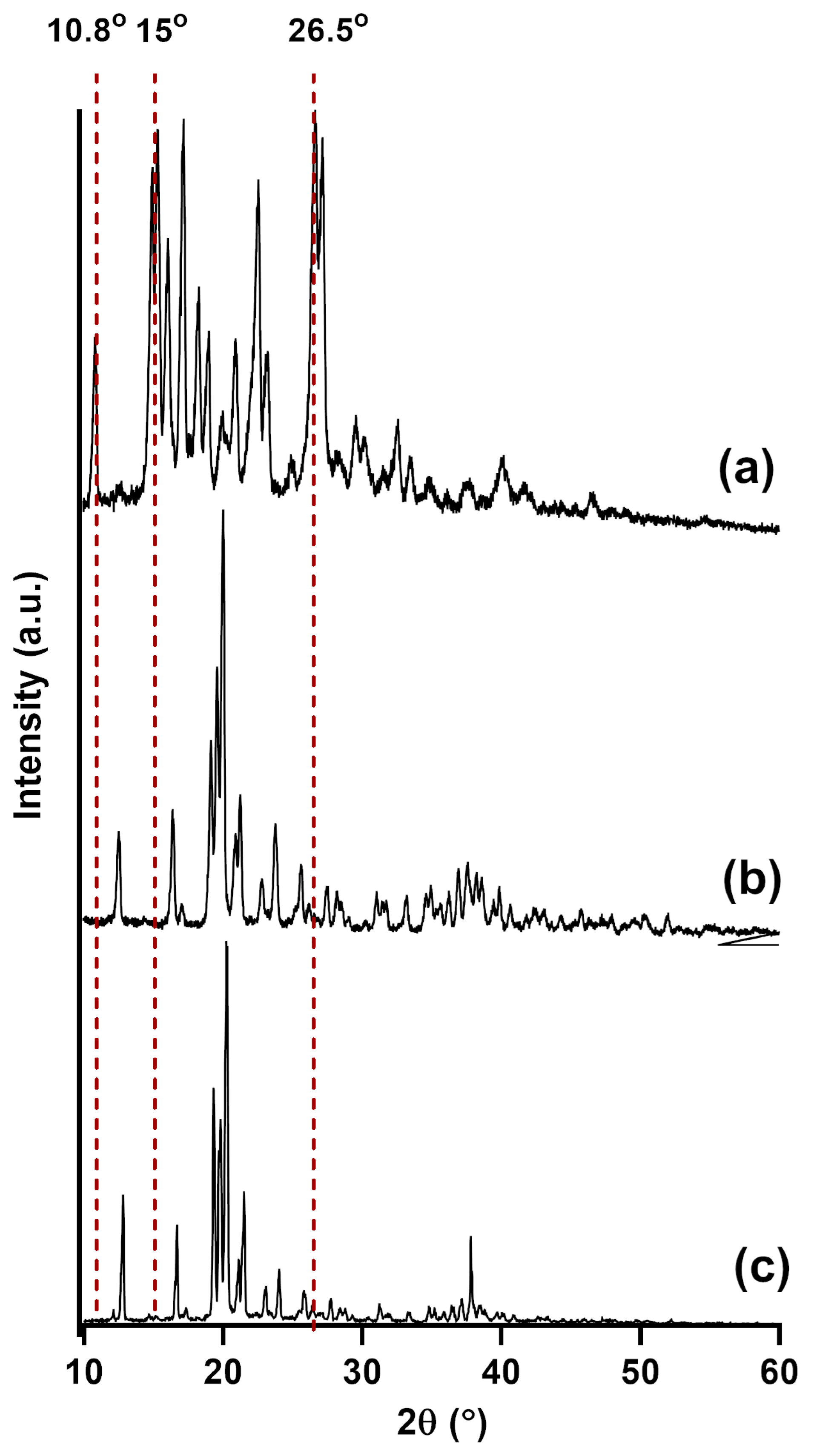

3.3. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD)

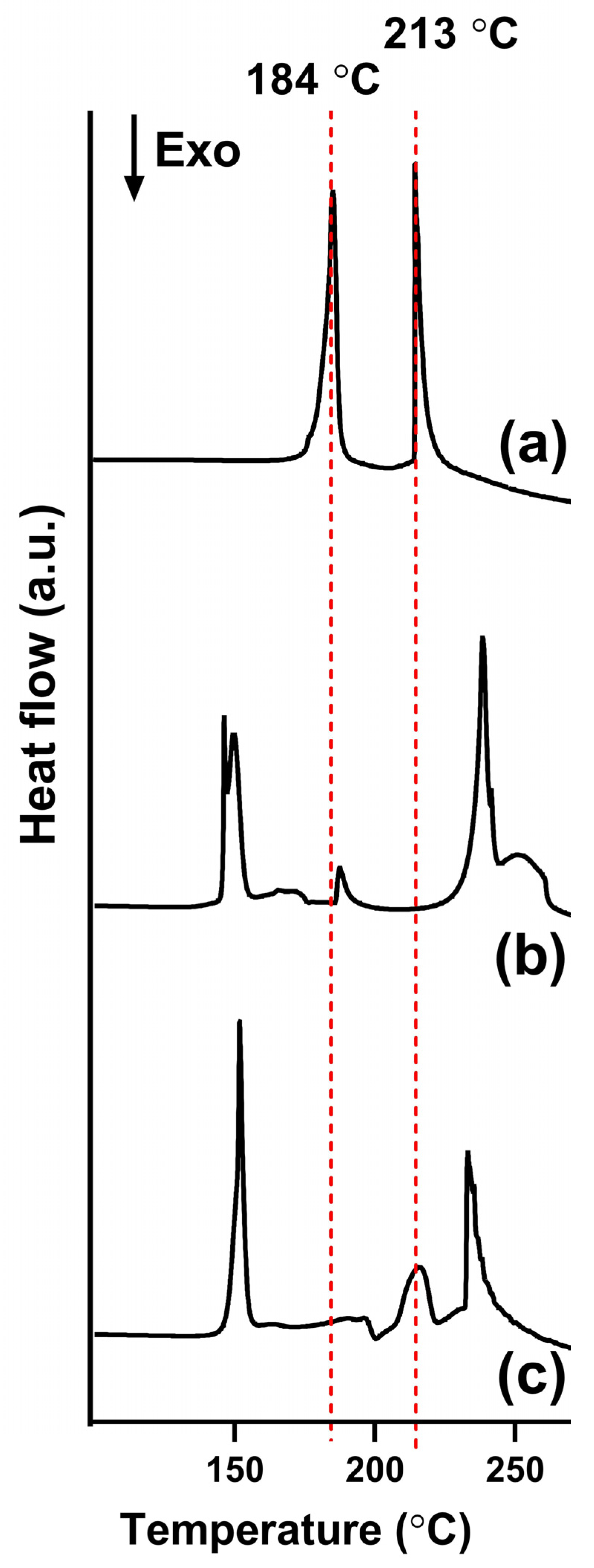

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

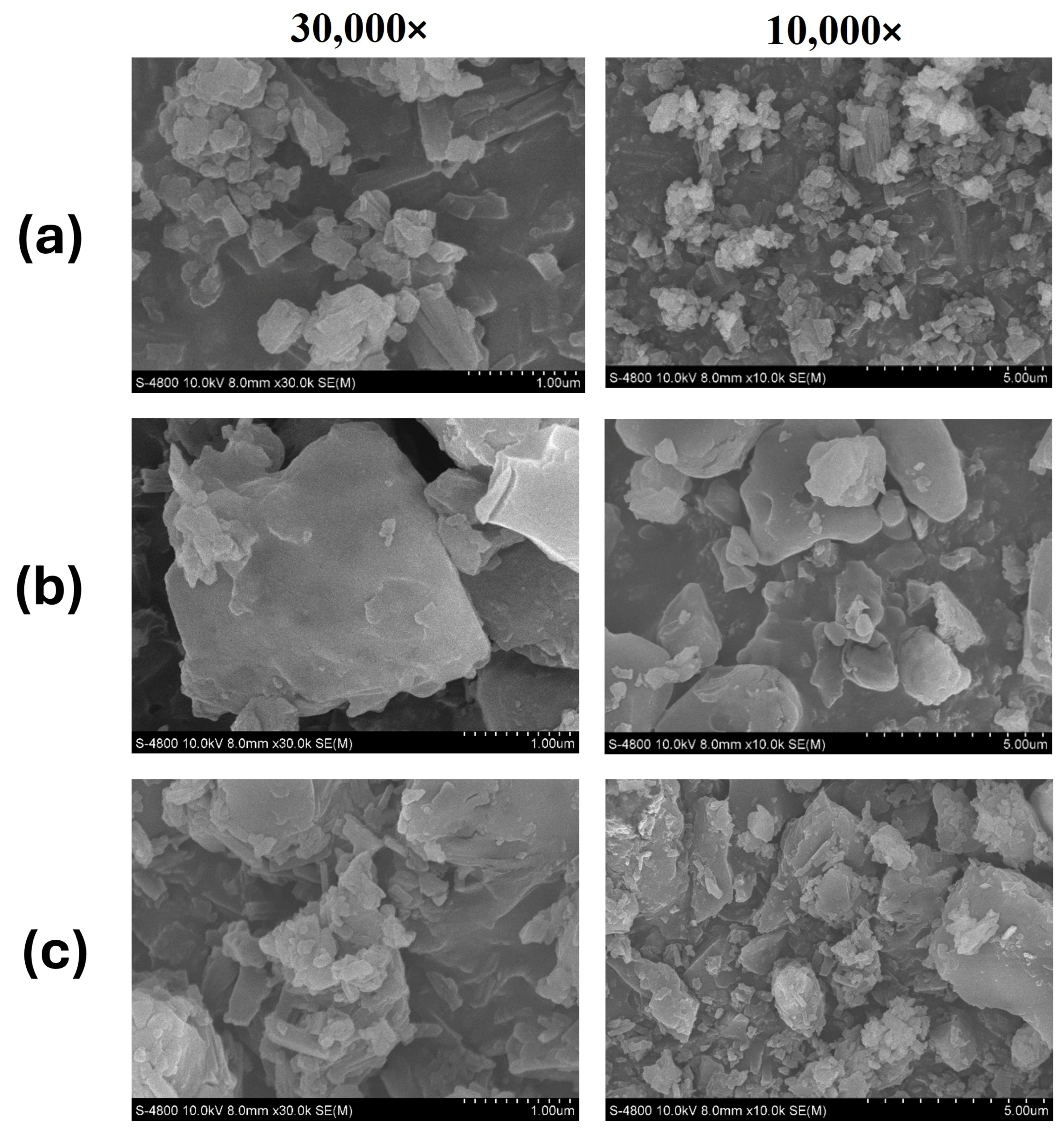

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

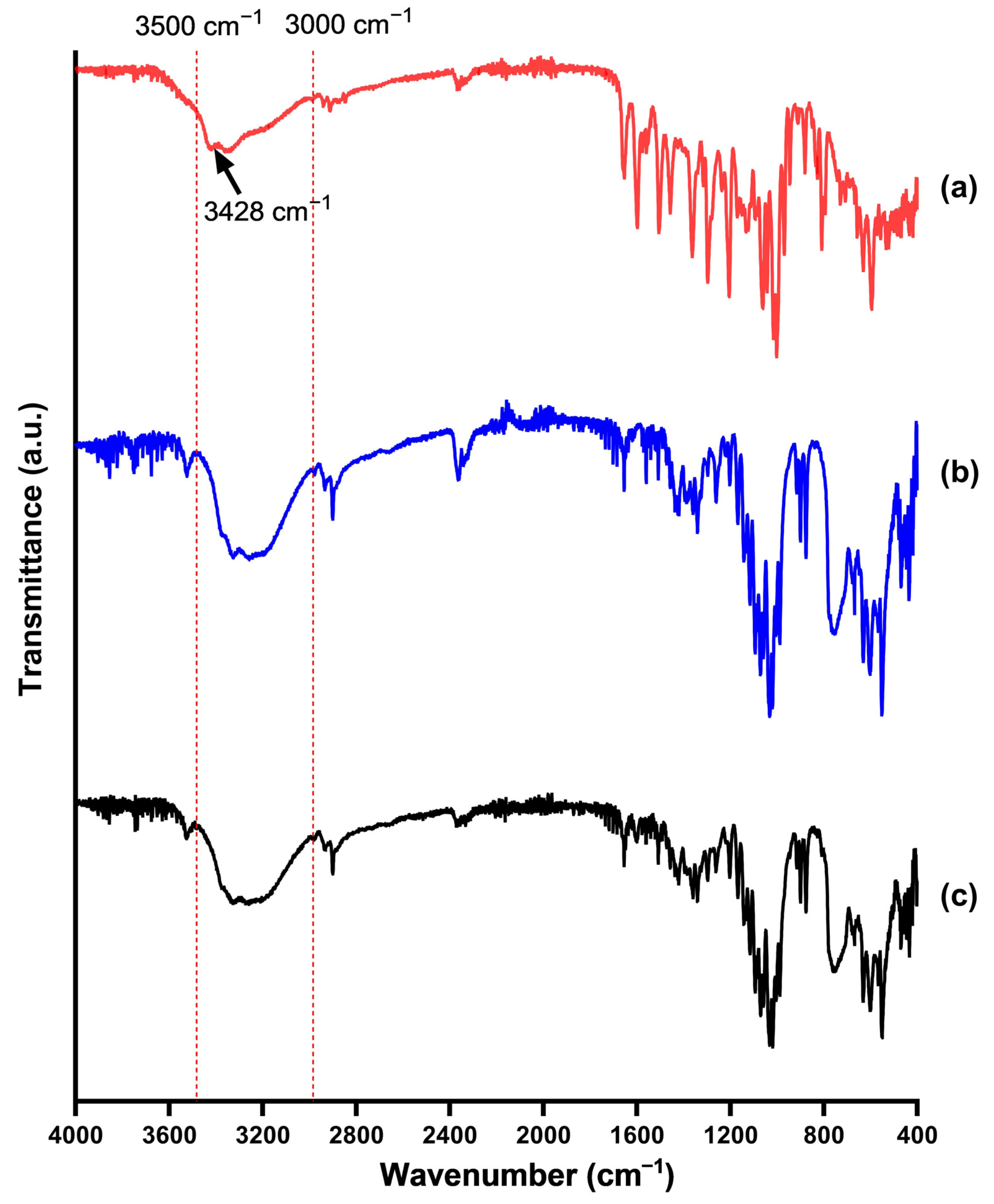

3.6. Fourier-Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

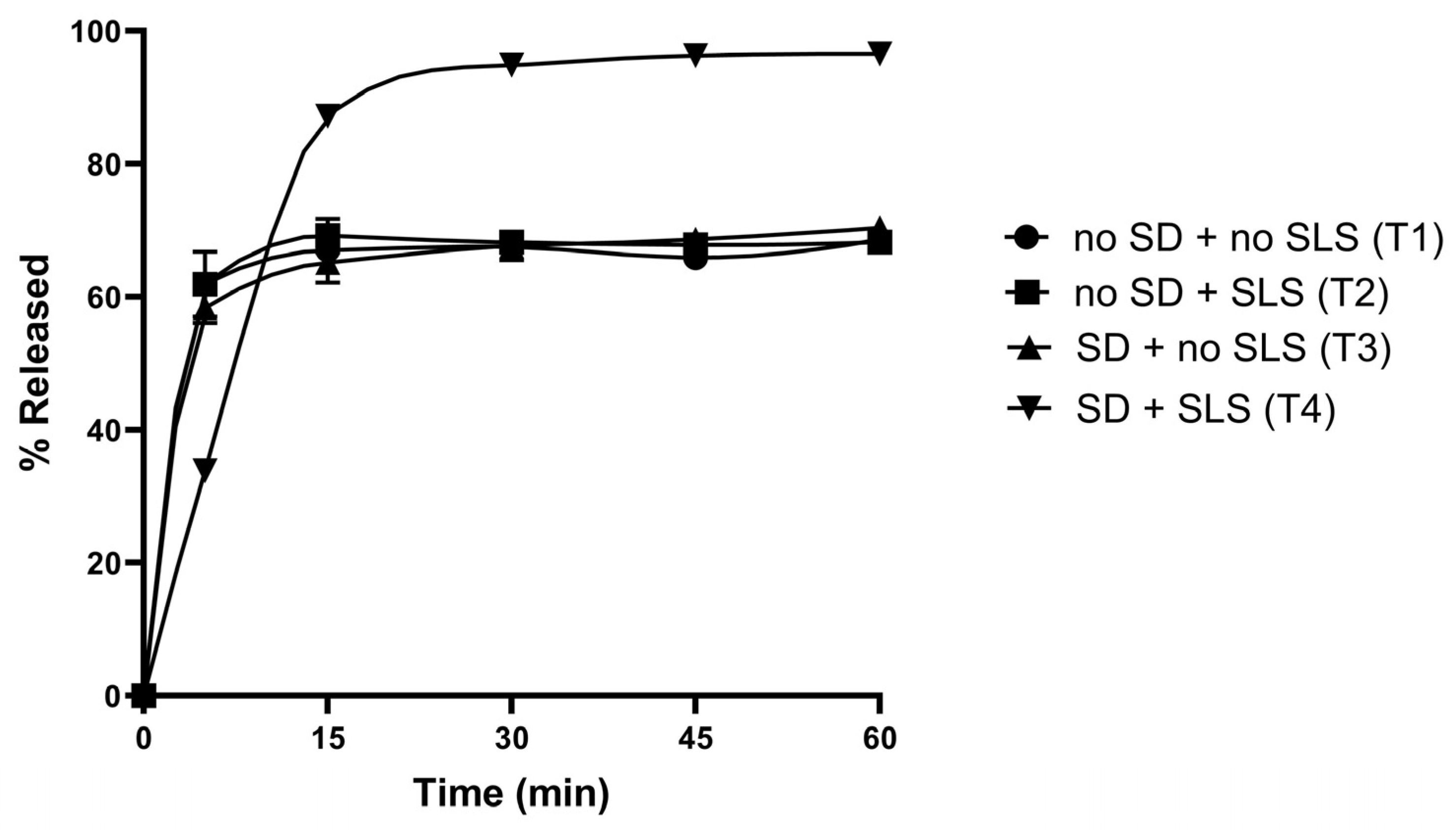

3.7. Formulations and Physicochemical Characterisations of Rutin-Loaded Tablets

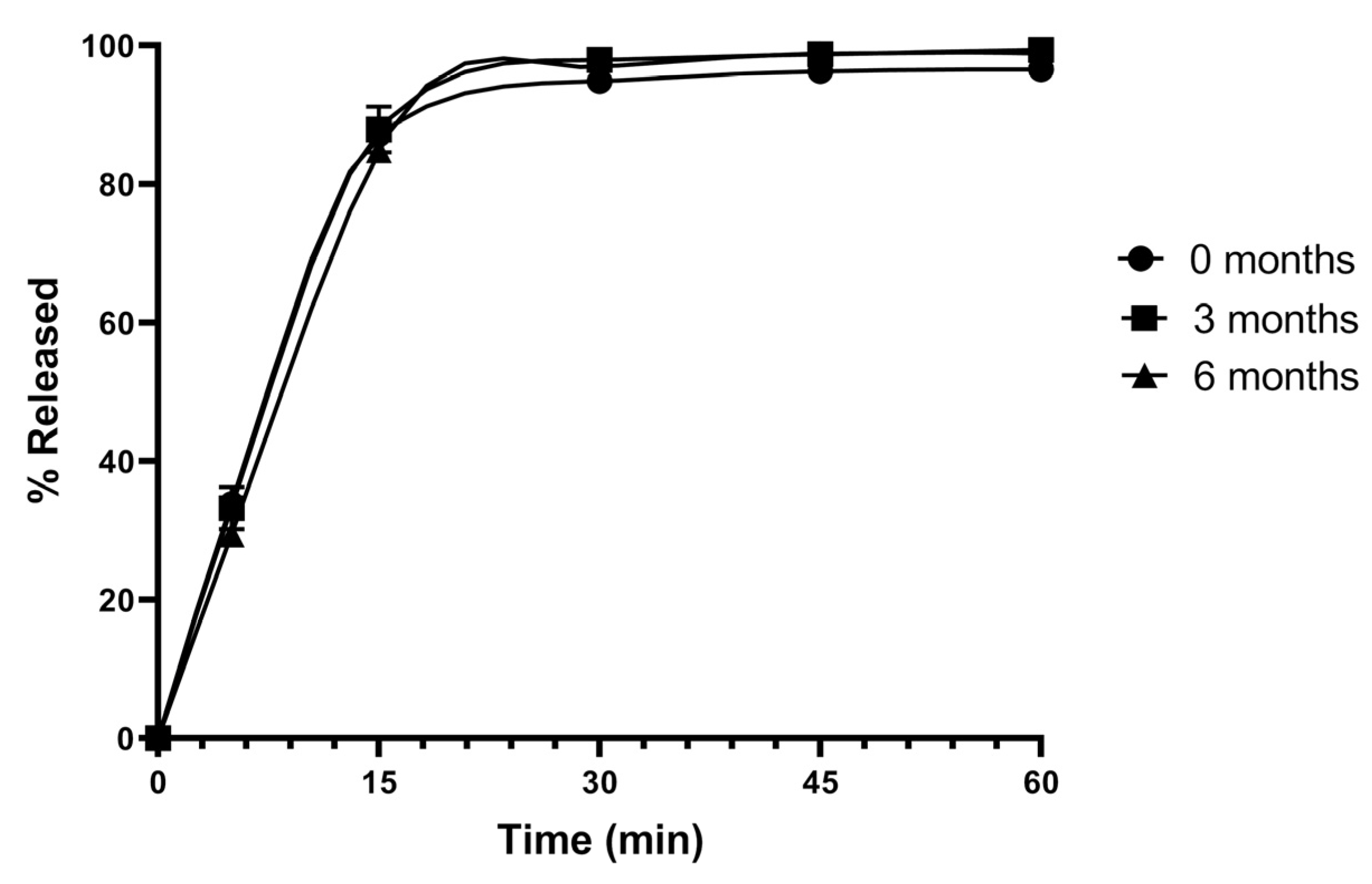

3.8. Stability Studies

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SD | Solid dispersion |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray diffraction |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier transformed infrared |

| SLS | Sodium lauryl sulfate |

| PVP K30 | Polyvinyl pyrrolidone K30 |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonisation |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

References

- Kumari, L.; Choudhari, Y.; Patel, P.; Gupta, G.D.; Singh, D.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Bansal, K.K.; Kurmi, B.D. Advancement in Solubilization Approaches: A Step towards Bioavailability Enhancement of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Life 2023, 13, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamba, I.; Sombié, C.B.; Yabré, M.; Zimé-Diawara, H.; Yaméogo, J.; Ouédraogo, S.; Lechanteur, A.; Semdé, R.; Evrard, B. Pharmaceutical approaches for enhancing solubility and oral bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 204, 114513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K. Bioavailability Enhancement Techniques for Poorly Aqueous Soluble Drugs and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujbal, S.V.; Mitra, B.; Jain, U.; Gong, Y.; Agrawal, A.; Karki, S.; Taylor, L.S.; Kumar, S.; Zhou, Q. Pharmaceutical amorphous solid dispersion: A review of manufacturing strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2505–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, A.K.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B.; Wu, D.-T.; Atanasov, A.G.; Gul, K.; Zhang, J.-R.; Yang, Q.-Q.; Corke, H. The anticancer potential of the dietary polyphenol rutin: Current status, challenges, and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 832–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidinejad, A.; Jameson, G.B.; Singh, H. The Effect of pH and Sodium Caseinate on the Aqueous Solubility, Stability, and Crystallinity of Rutin towards Concentrated Colloidally Stable Particles for the Incorporation into Functional Foods. Molecules 2022, 27, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, H.; Meidy Nurintan Savitri, O.; Primaharinastiti, R.; Agus Syamsur Rijal, M. A lyophilized surfactant-based rutin formulation with improved physical characteristics and dissolution for oral delivery. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bhargava, D.; Thakkar, A.; Arora, S. Drug carrier systems for solubility enhancement of BCS class II drugs: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2013, 30, 217–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tang, L.; Tian, F.; Ding, Q.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.-R.; Mei, X. Rutin Cocrystals with Improved Solubility, Bioavailability, and Bioactivities. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 5637–5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowska, M.; Mizera, M.; Piotrowska, H.; Szymanowska-Powałowska, D.; Lewandowska, K.; Goscianska, J.; Pietrzak, R.; Bednarski, W.; Majka, Z.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Complex of rutin with β-cyclodextrin as potential delivery system. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Song, M.; Ma, M.; Song, J.; Cao, F.; Qin, Q. Preparation, Characterization and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Rutin–Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes. Molecules 2023, 28, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.I.; Dominguez, G.P.; Echeverry, S.M.; Valderrama, I.H.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A.; Aragón, M. Enhanced oral bioavailability of rutin by a self-emulsifying drug delivery system of an extract of calyces from Physalis peruviana. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 66, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, A.S.; Quelhas, S.; Silva, A.M.; Souto, E.B. Nanoemulsions for delivery of flavonoids: Formulation and in vitro release of rutin as model drug. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2014, 19, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M. Development and optimization of oral nanoemulsion of rutin for enhancing its dissolution rate, permeability, and oral bioavailability. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2022, 27, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; El-Biyally, E.; Sakran, W. An Innovative Approach for Formulation of Rutin Tablets Targeted for Colon Cancer Treatment. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.S.; Lima, F.; Ros, S.D.; Bulhões, L.O.S.; de Carvalho, L.M.; Beck, R.C.R. Nanostructured Systems Containing Rutin: In Vitro Antioxidant Activity and Photostability Studies. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Cao, M.; Zhang, H.; Qin, S.; Tian, B.; Zhang, J. Preparation of zein-rutin supramolecular nanoparticles using pH-ultrasound-shifting: Binding mechanism, functional properties, and in vitro release kinetics. Food Chem. 2025, 483, 144087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.; Sarmento, B.; Costa, P. Solid dispersions as strategy to improve oral bioavailability of poor water soluble drugs. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.; Marques, S.; das Neves, J.; Sarmento, B. Amorphous solid dispersions: Rational selection of a manufacturing process. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 100, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, E.M.; Filho, J.M.B.; do Nascimento, T.G.; Macêdo, R.O. Thermal characterization of the quercetin and rutin flavonoids. Thermochim. Acta 2002, 392–393, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, J.; Xu, W.; Lehto, V.-P. Mesoporous systems for poorly soluble drugs—Recent trends. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 536, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; Li, T.; Bu, T.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X. Role of polymers in the physical and chemical stability of amorphous solid dispersion: A case study of carbamazepine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 169, 106086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, N.; Wu, B.; Lu, Y.; Guan, T.; Wu, W. Physical characterization of lansoprazole/PVP solid dispersion prepared by fluid-bed coating technique. Powder Technol. 2008, 182, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Heo, E.-J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Byun, J.-M.; Cheon, S.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Cho, K.H.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Poorly Water-Soluble Celecoxib as Solid Dispersions Containing Nonionic Surfactants Using Fluidized-Bed Granulation. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.-J.; Kim, S.T.; Lee, K.; Oh, E. Improved bioavailability and antiasthmatic efficacy of poorly soluble curcumin-solid dispersion granules obtained using fluid bed granulation. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2014, 24, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewson, C.F.; Naghski, J. Some physical properties of rutin. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1952, 41, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indireddy, T.; Kuber, R. Application of Response Surface Methodology for the Development of an Innovative Stability Indicating UHPLC Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Rutin and Catechin in Corn Silk Extract Tablets. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 78, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogi, V. A New Challenge for the Old Excipient Calcium Carbonate: To Improve the Dissolution Rate of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Park, C.; Oh, E.; Lee, B.-J. Improving the dissolution rate of a poorly water-soluble drug via adsorption onto pharmaceutical diluents. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 35, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.K.; Bogner, R.H. Application of mesoporous silicon dioxide and silicate in oral amorphous drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Keck, C.M.; Müller, R.H. Preparation and tableting of long-term stable amorphous rutin using porous silica. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 113, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhao, H.; Fang, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhao, L. Lactose in tablets: Functionality, critical material attributes, applications, modifications and co-processed excipients. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kampen, A.; Kohlus, R. Systematic process optimisation of fluid bed coating. Powder Technol. 2017, 305, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, P.; Poovizhi, P.; Ng, W.K.; Tan, R.B.H. Amorphous formulations for dissolution and bioavailability enhancement of poorly soluble APIs. Powder Technol. 2015, 285, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, A.O.; Kaialy, W.; Hussain, T.; Al-Hamidi, H.; Nokhodchi, A.; Conway, B.R.; Asare-Addo, K. Freeze-dried crystalline dispersions: Solid-state, triboelectrification and simultaneous dissolution improvements. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahiwala, A. Formulation approaches in enhancement of patient compliance to oral drug therapy. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatini, B.; Romano Perinelli, D.; Filippo Palmieri, G.; Cespi, M.; Bonacucina, G. Sodium lauryl sulfate as lubricant in tablets formulations: Is it worth? Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 643, 123265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dun, J.; Osei-Yeboah, F.; Boulas, P.; Lin, Y.; Sun, C.C. A systematic evaluation of dual functionality of sodium lauryl sulfate as a tablet lubricant and wetting enhancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 552, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | Formulation Code | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | |

| Rutin | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Lactose monohydrate | 300 | - | - | - | 225 | 375 | |

| Mannitol | - | 300 | - | - | - | - | |

| Microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH101) | - | - | 300 | - | - | - | - |

| Silicon dioxide | - | - | - | 300 | - | - | - |

| Calcium carbonate | - | - | - | - | 300 | - | - |

| Total weight (g) | 330 | 330 | 330 | 330 | 330 | 255 | 405 |

| Composition | Formulation Code | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| Rutin | 50 | 50 | - | - |

| Lactose monohydrate | 500 | 500 | - | - |

| Rutin–lactose solid dispersion (F1) | - | - | 550 | 550 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH101) | 269 | 269 | 269 | 269 |

| PVP K30 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| Crosscamellose sodium | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| SLS | - | 30 | - | 30 |

| Magnesium stearate | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Tablet weight (mg) | 900 | 900 | 900 | 900 |

| Formulation Code | Drug Content (%) | Hardness (N) | Disintegration Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 103.5 ± 1.2 | 41.3 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 0.5 |

| T2 | 102.9 ± 0.9 | 40.8 ± 0.5 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

| T3 | 103.3 ± 0.4 | 40.6 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| T4 | 98.2 ± 0.7 | 41.6 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.T.-T.; Tran, H.K.-T.; Huynh, T.T.-N.; Vo, V.H.-B.; Le, C.T.-T.; Saha, T. Improved Dissolution of Poorly Water-Soluble Rutin via Solid Dispersion Prepared Using a Fluid-Bed Coating System. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121559

Nguyen HV, Nguyen NT-T, Tran HK-T, Huynh TT-N, Vo VH-B, Le CT-T, Saha T. Improved Dissolution of Poorly Water-Soluble Rutin via Solid Dispersion Prepared Using a Fluid-Bed Coating System. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121559

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Hien V., Nga Thi-Thuy Nguyen, Huong Kim-Thien Tran, Thuy Thi-Nhu Huynh, Vi Huyen-Bao Vo, Cuc Thi-Thu Le, and Tushar Saha. 2025. "Improved Dissolution of Poorly Water-Soluble Rutin via Solid Dispersion Prepared Using a Fluid-Bed Coating System" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121559

APA StyleNguyen, H. V., Nguyen, N. T.-T., Tran, H. K.-T., Huynh, T. T.-N., Vo, V. H.-B., Le, C. T.-T., & Saha, T. (2025). Improved Dissolution of Poorly Water-Soluble Rutin via Solid Dispersion Prepared Using a Fluid-Bed Coating System. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121559