Advances in β-Galactosidase Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Enzyme Delivery Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

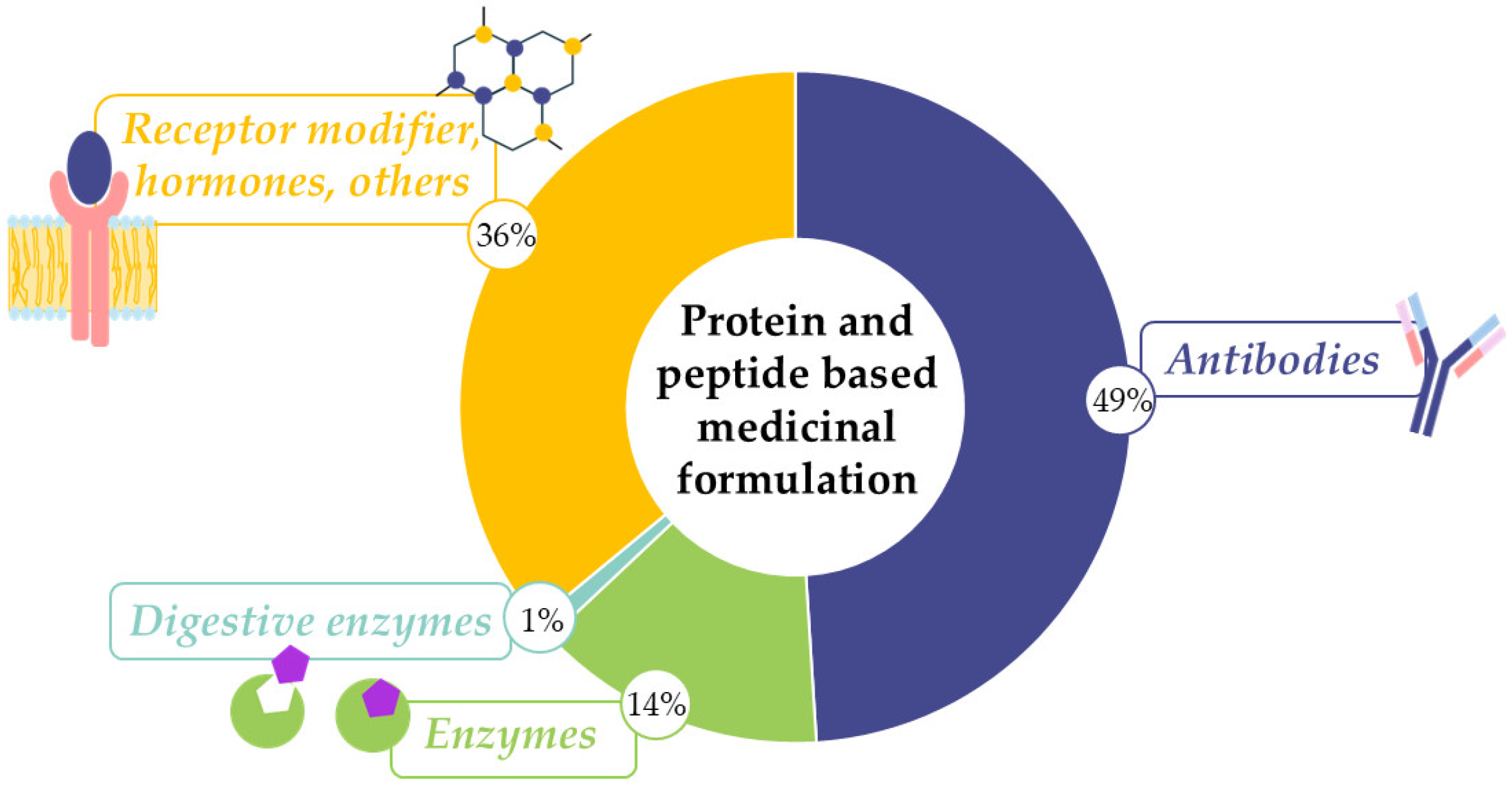

1.1. Applications for Enzyme Therapies

1.2. Lactase-Based Therapies and Significance of Lactose Intolerance

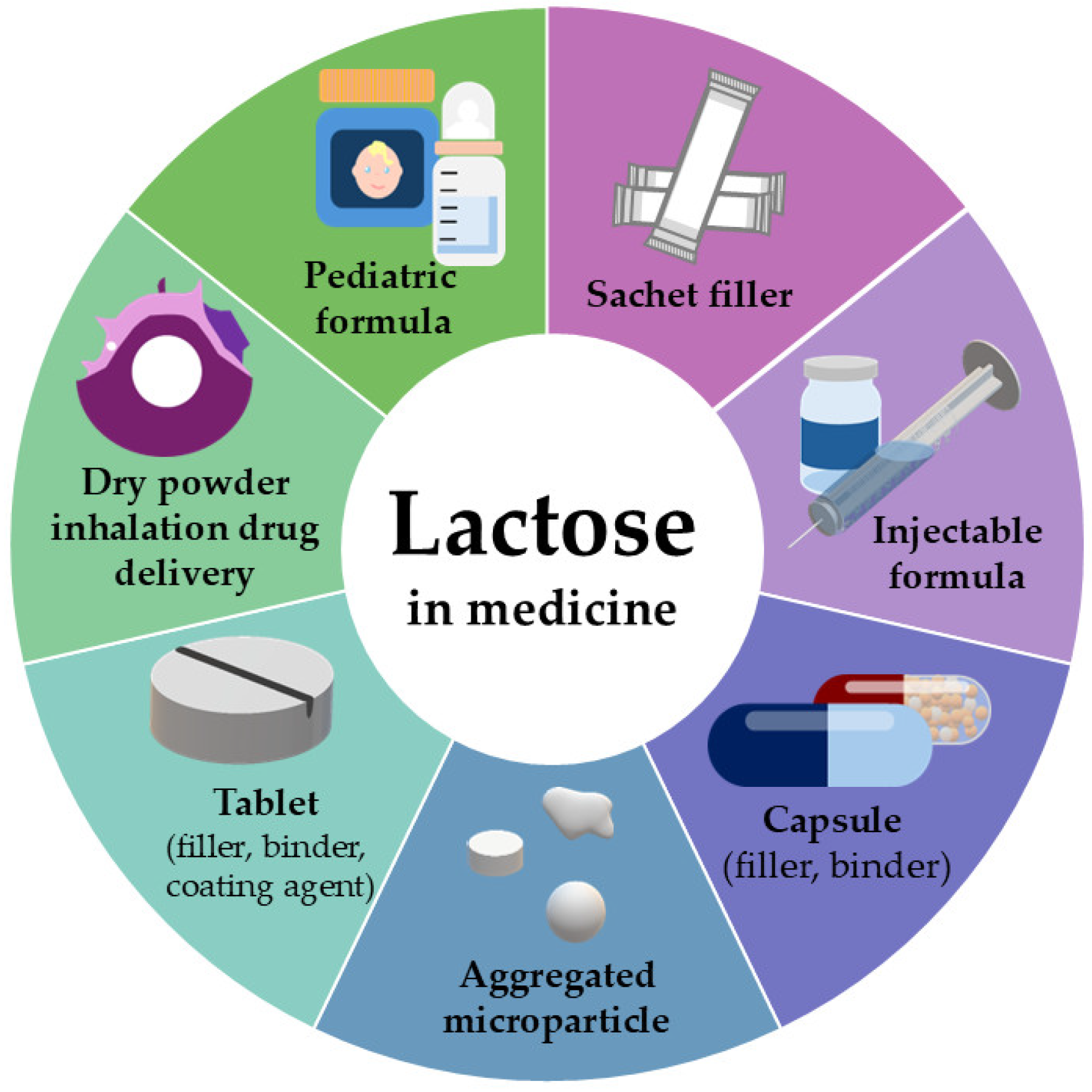

1.3. Lactose as Pharmaceutical Excipient

1.4. Characterization of Lactase Enzyme (Physical–Chemical Properties) and Industrial Applications

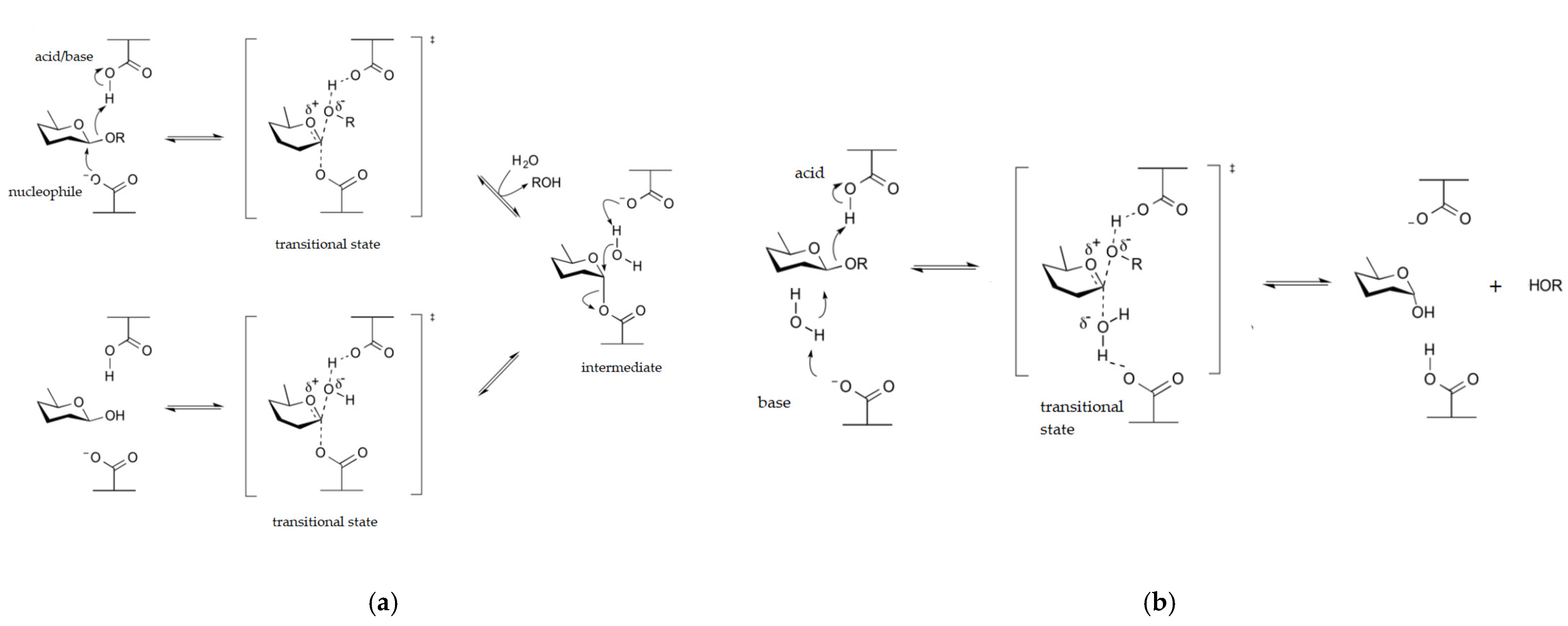

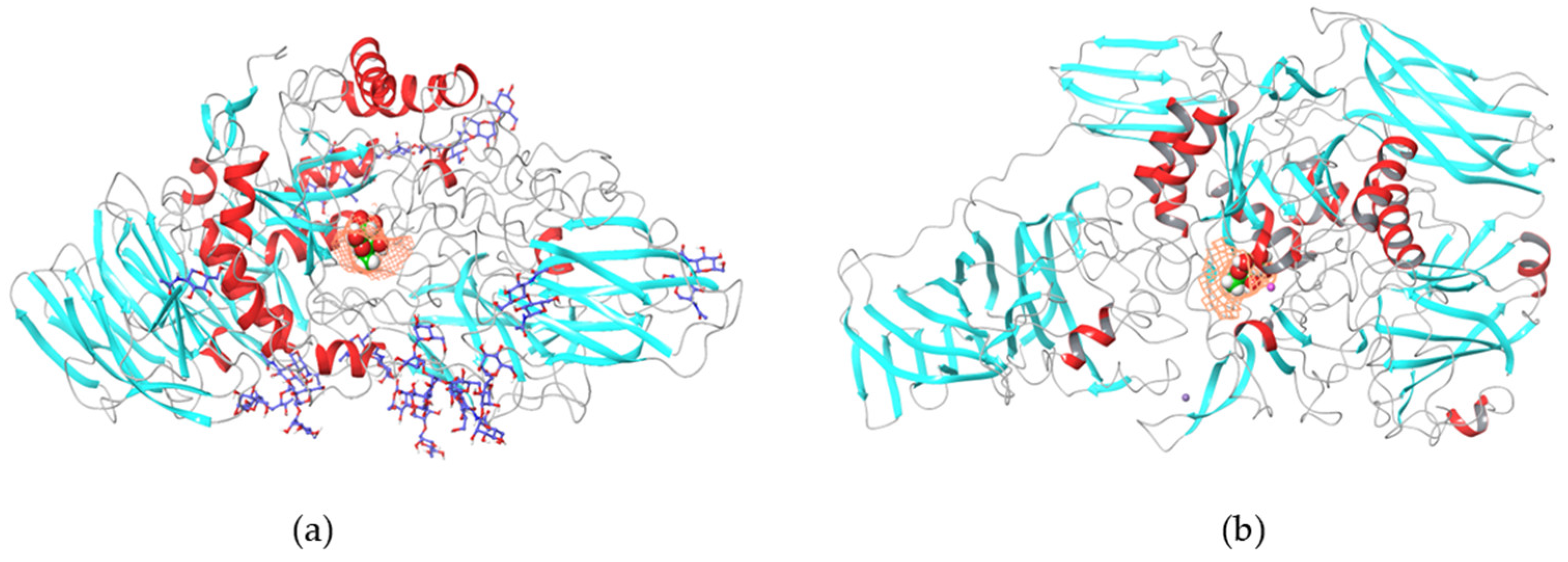

1.4.1. β-Galactosidases

1.4.2. Lactase Enzyme

2. Materials and Methods

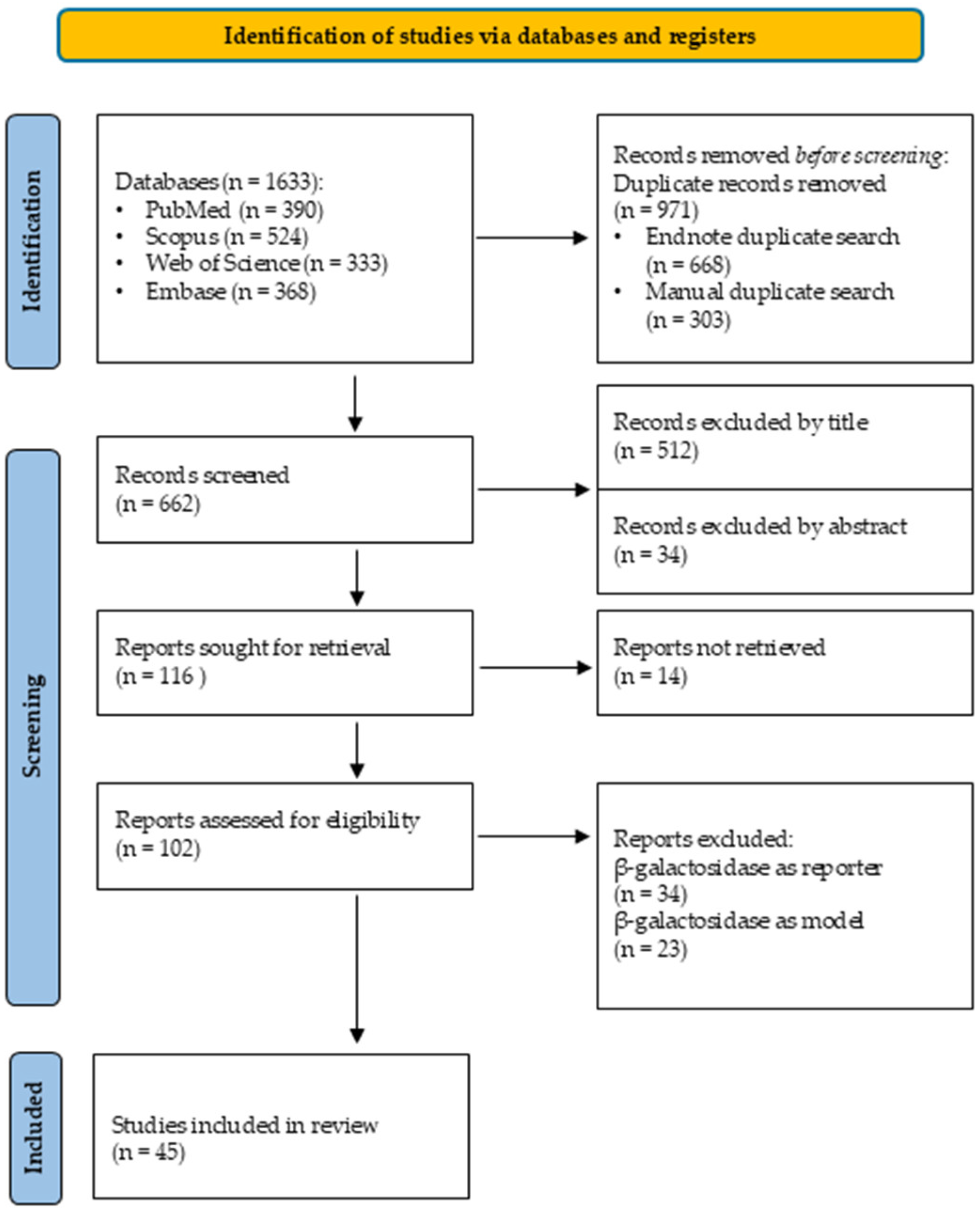

2.1. Systematic Search

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.2. Search Strategy

2.1.3. Data Collection and Extraction

3. Results

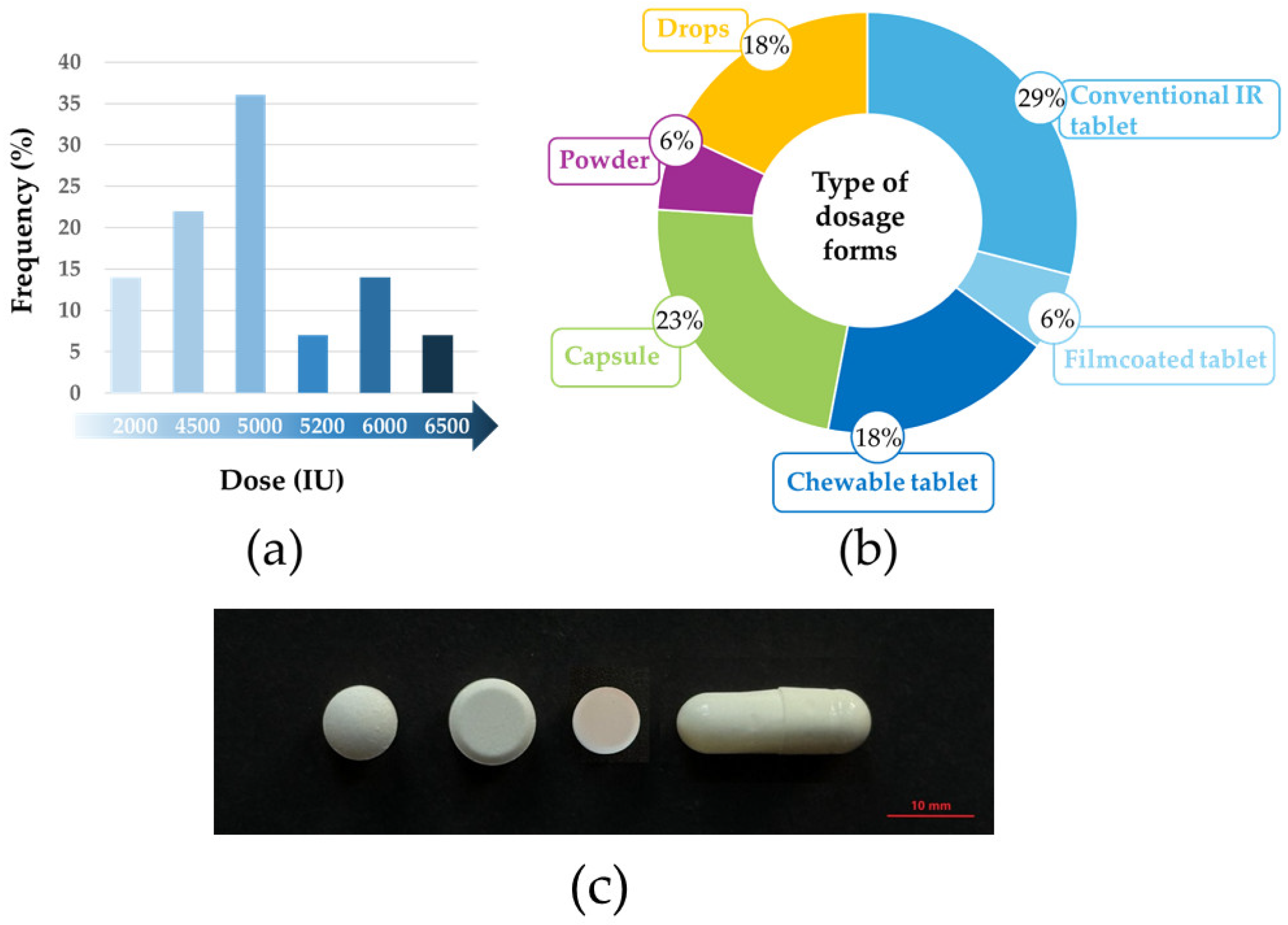

3.1. Case Study: Diversity of Lactase Products in Hungary

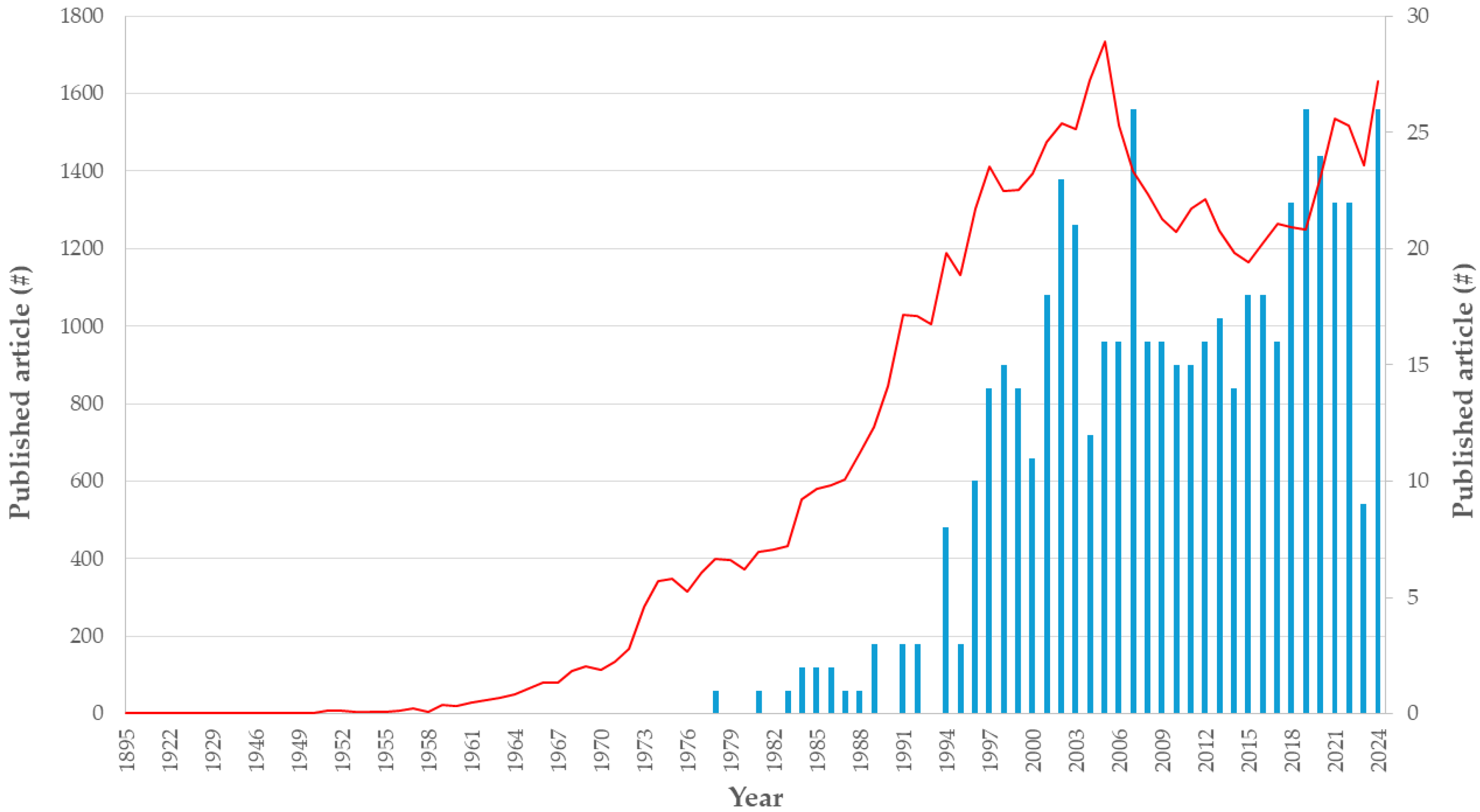

3.2. Database Search

4. Discussion

4.1. Applications of the β-Galactosidase Enzyme

4.2. Therapy for Lactose Intolerance

4.3. β-Galactosidase-Containing Pharmaceutical Formulations

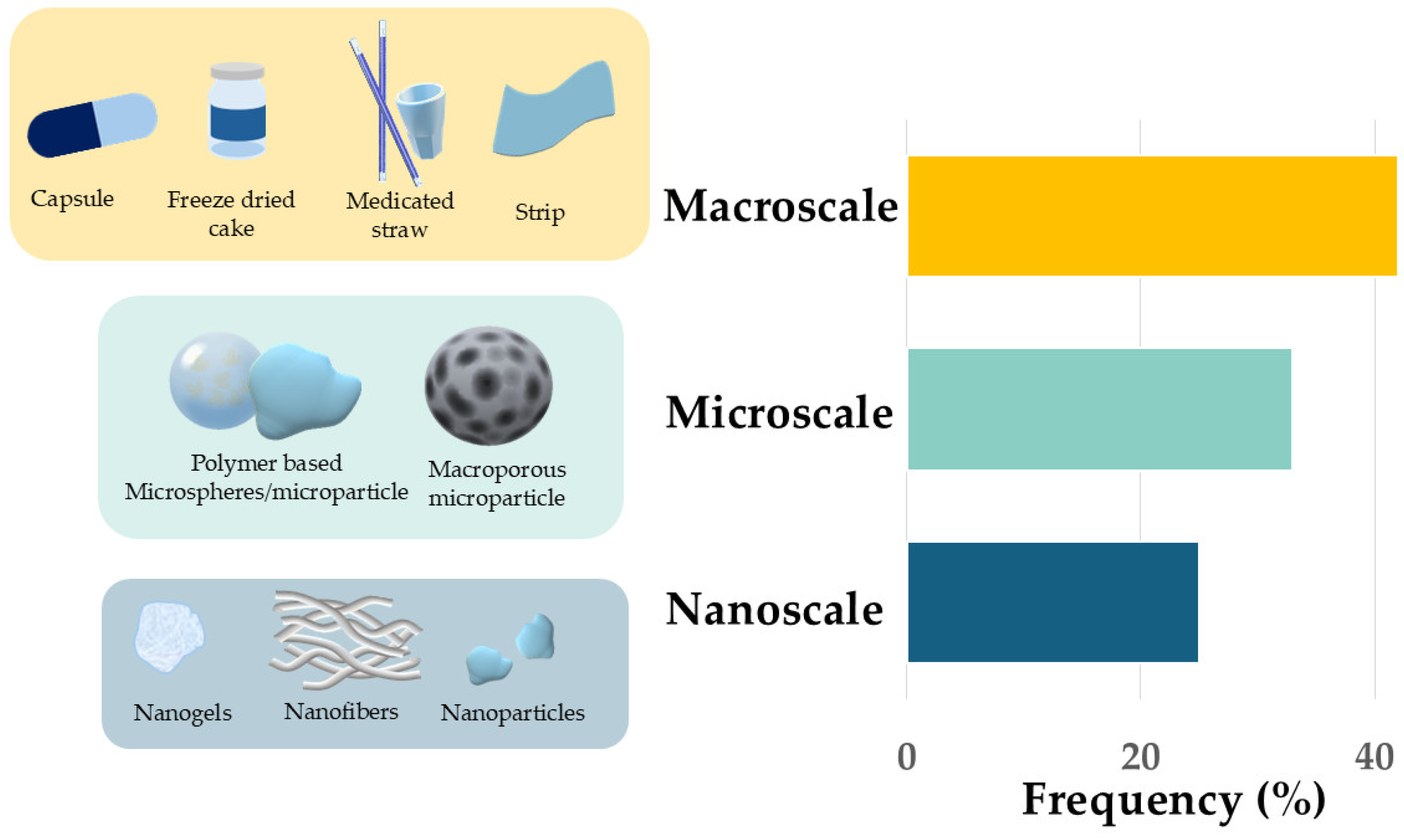

4.4. Enzyme Delivery Systems

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hennigan, J.N.; Lynch, M.D. The past, present, and future of enzyme-based therapies. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, M.; Lombardero, L.; Gómez-González, A.; Solari, C.; Angulo-Barturen, I.; Acera, A.; Vecino, E.; Astigarraga, E.; Barreda-Gómez, G. Enzyme Therapy: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugidos-Rodríguez, S.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: A review. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 4056–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselwitz, B.; Pohl, D.; Frühauf, H.; Fried, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; Fox, M. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013, 1, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, O.J.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Kuha, J.; Luyten, J. Sales Revenues for New Therapeutic Agents Approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration from 1995 to 2014. Value Health 2024, 27, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. The Pharmaceutical Industry in 2024: An Analysis of the FDA Drug Approvals from the Perspective of Molecules. Molecules 2025, 30, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinch, M.S. An overview of FDA-approved biologics medicines. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Gokarn, Y.; Mitragotri, S. Non-invasive delivery strategies for biologics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.-J. Recent advances in bioreactor engineering. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekshah, O.M.; Chen, X.; Nomani, A.; Sarkar, S.; Hatefi, A. Enzyme/Prodrug Systems for Cancer Gene Therapy. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016, 2, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Koplányi, G.; Kenéz, B.; Balogh-Weiser, D. Nanoformulation of Therapeutic Enzymes: A Short Review. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2023, 67, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J.R.; Panayiotou, V.; Agnello, G.; Georgiou, G.; Stone, E.M. Engineering Reduced-Immunogenicity Enzymes for Amino Acid Depletion Therapy in Cancer. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 502, pp. 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- DrugBank Online “Database for Drug Categories”. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Datta, S.; Rajnish, K.N.; George Priya Doss, C.; Melvin Samuel, S.; Selvarajan, E.; Zayed, H. Enzyme therapy: A forerunner in catalyzing a healthy society? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troll, W.; Wiesner, R.; Frenkel, K. Anticarcinogenic Action of Protease Inhibitors. In Advances in Cancer Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; Volume 49, pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gremmler, L.; Kutschan, S.; Dörfler, J.; Büntzel, J.; Büntzel, J.; Hübner, J. Proteolytic Enzyme Therapy in Complementary Oncology: A Systematic Review. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 3213–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, C.G.; Fahnehjelm, K.T.; Pitz, S.; Guffon, N.; Koseoglu, S.T.; Harmatz, P.; Scarpa, M. Systemic therapies for mucopolysaccharidosis: Ocular changes following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation or enzyme replacement therapy—A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010, 38, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Cai, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, S. Advanced application of stimuli-responsive drug delivery system for inflammatory arthritis treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, G.D.; Kazsoki, A.; Gyarmati, B.; Szilágyi, A.; Vasvári, G.; Katona, G.; Szente, L.; Zelkó, R.; Poppe, L.; Balogh-Weiser, D.; et al. Nanofibrous Formulation of Cyclodextrin Stabilized Lipases for Efficient Pancreatin Replacement Therapies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safary, A.; Akbarzadeh Khiavi, M.; Mousavi, R.; Barar, J.; Rafi, M.A. Enzyme replacement therapies: What is the best option? Bioimpacts 2018, 8, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, S.; López-Leiva, M.H. Oligosaccharide Formation During Enzymatic Lactose Hydrolysis: A Literature Review. J. Food Prot. 1990, 53, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayless, T.M.; Brown, E.; Paige, D.M. Lactase Non-persistence and Lactose Intolerance. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Marzetti, E.; Pellegrino, S.; Montalto, M. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance in older adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2024, 27, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stourman, N.; Moore, J. Analysis of lactase in lactose intolerance supplements. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 46, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolchynska, M. Does Preprandial Oral Lactase Supplement Reduce Abdominal Pain in Lactose-Intolerant Adult Patients After a Lactose-Containing Meal? Master’s Thesis, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 30 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi, A.; Ishayek, N. Lactose Intolerance, Dairy Avoidance, and Treatment Options. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvelä, I.; Torniainen, S.; Kolho, K.-L. Molecular genetics of human lactase deficiencies. Ann. Med. 2009, 41, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusynyk, R.A.; Still, C.D. Lactose intolerance. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2001, 101, S10–S12. [Google Scholar]

- Baijal, R.; Tandon, R.K. Effect of lactase on symptoms and hydrogen breath levels in lactose intolerance: A crossover placebo-controlled study. JGH Open 2021, 5, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, M.; Curigliano, V.; Santoro, L.; Vastola, M.; Cammarota, G.; Manna, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Management and treatment of lactose malabsorption. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Raymundo, A.; Moreira, J.B.; Prista, C. Exploring the Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation as a Clean Label Alternative for Use in Yogurt Production. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zheng, J.; Han, X.; Yang, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, W.; Lu, Y. Advances in Low-Lactose/Lactose-Free Dairy Products and Their Production. Foods 2023, 12, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagshawe, K.D.; Sharma, S.K.; Begent, R.H.J. Antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) for cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004, 4, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almukainzi, M.; Alanazi, R.; Alzahrani, R.; Almujhad, L. Using Medications Containing Lactose as an Excipient for Lactose Intolerance Patients: Insights of Clinical Practices and Regulators Roles. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. (2003) 2025, 65, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, S.; Marescotti, F.; Sanmartin, C.; Macaluso, M.; Taglieri, I.; Venturi, F.; Zinnai, A.; Facioni, M.S. Lactose: Characteristics, Food and Drug-Related Applications, and Its Possible Substitutions in Meeting the Needs of People with Lactose Intolerance. Foods 2022, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Király, M.; Kiss, B.D.; Horváth, P.; Drahos, L.; Mirzahosseini, A.; Pálfy, G.; Antal, I.; Ludányi, K. Investigating thermal stability based on the structural changes of lactase enzyme by several orthogonal methods. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, R.G.; Garcia-Recio, V.; Garrosa, M.; Rojo, M.Á.; Jiménez, P.; Girbés, T.; Cordoba-Diaz, M.; Cordoba-Diaz, D. Human Health Effects of Lactose Consumption as a Food and Drug Ingredient. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burande, A.S.; Dhakare, S.P.; Dondulkar, A.O.; Gatkine, T.M.; Bhagchandani, D.O.; Sonule, M.S.; Thakare, V.M.; Prasad, S.K. A review on the role of co-processed excipients in tablet formulations. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara Garcia, R.A.; Afonso Urich, J.A.; Afonso Urich, A.I.; Jeremic, D.; Khinast, J. Application of Lactose Co-Processed Excipients as an Alternative for Bridging Pharmaceutical Unit Operations: Manufacturing an Omeprazole Tablet Prototype via Direct Compression. Sci. Pharm. 2025, 93, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Yan, B.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y. A Novel Lactose/MCC/L-HPC Triple-Based Co-Processed Excipients with Improved Tableting Performance Designed for Metoclopramide Orally Disintegrating Tablets. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrojewicz, Z.; Zyskowska, K.; Wasiuk, S. Lactose in drugs and lactose intolerance—Realities and myths. Paediatr. Fam. Med. 2018, 14, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D.; Noro, J.; Silva, C.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Nogueira, E. Protective Effect of Saccharides on Freeze-Dried Liposomes Encapsulating Drugs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Tan, X.; Hou, J.; Gong, Z.; Qin, X.; Nie, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, S. Separation, purification, structure characterization, and immune activity of a polysaccharide from Alocasia cucullata obtained by freeze-thaw treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarmpi, P.; Flanagan, T.; Meehan, E.; Mann, J.; Fotaki, N. Biopharmaceutical aspects and implications of excipient variability in drug product performance. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 111, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, P.; Du, J.; Smyth, H.D.C. Evaluation of Granulated Lactose as a Carrier for DPI Formulations 1: Effect of Granule Size. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadala, P.; Waud, J.P.; Matthews, S.B.; Green, J.T.; Campbell, A.K. Quantifying the ‘hidden’ lactose in drugs used for the treatment of gastrointestinal conditions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Information for the Package Leaflet Regarding Lactose Used 4 as an Excipient in Medicinal Products for Human Use, EMA/CHMP/186428/2016; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Juers, D.H.; Matthews, B.W.; Huber, R.E. LacZ β-galactosidase: Structure and function of an enzyme of historical and molecular biological importance. Protein Sci. 2012, 21, 1792–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotman, B. Measurement of activity of single molecules of beta-D-galactosidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1961, 47, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, S.; Walsh, G. Application relevant studies of fungal beta-galactosidases with potential application in the alleviation of lactose intolerance. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 149, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosova, Z.; Rosenberg, M.; Rebroš, M. Perspectives and applications of immobilised β-galactosidase in food industry—A review. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.; Akram, A.; Halim, S.A.; Tassaduq, R. Sources of β-galactosidase and its applications in food industry. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Coutinho, P.M.; Rancurel, C.; Bernard, T.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): An expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D233–D238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhacene, K.; Elena-Florentina, G.; Blaga, A.; Dhulster, P.; Pinteala, M.; Froidevaux, R. Simple eco-friendly β-galactosidase immobilization on functionalized magnetic particles for lactose hydrolysis. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2015, 14, 631–638. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado, E.; Camacho, F.; Luzón, G.; Vicaria, J.M. A new kinetic model proposed for enzymatic hydrolysis of lactose by a β-galactosidase from Kluyveromyces fragilis. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2002, 31, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrissat, B.; Davies, G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1997, 7, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott, M.L. Catalytic mechanism of enzymic glycosyl transfer. Chem. Rev. 1990, 90, 1171–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, M.L.; Gray, J.I.; Stine, C.M. Beta-Galactosidase: Review of Recent Research Related to Technological Application, Nutritional Concerns, and Immobilization. J. Dairy Sci. 1981, 64, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmerdam, A.; Boom, R.M.; Janssen, A.E. β-galactosidase stability at high substrate concentrations. Springerplus 2013, 2, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, T.K.; Kirshner, S.L.; Singer, D.S. Measure of transient transfection efficiency using beta-galactosidase protein. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 244, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legigan, T.; Clarhaut, J.; Tranoy-Opalinski, I.; Monvoisin, A.; Renoux, B.; Thomas, M.; Le Pape, A.; Lerondel, S.; Papot, S. The first generation of β-galactosidase-responsive prodrugs designed for the selective treatment of solid tumors in prodrug monotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 11606–11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Ding, L.; Cai, L.; Mao, F.; Shi, D.; Hoffman, R.M.; Li, J.; Jia, L. Pro-senescence neddylation inhibitor combined with a senescence activated β-galactosidase prodrug to selectively target cancer cells. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, M.F.; Irazoqui, J.M.; Amadio, A.F. β-Galactosidases from a Sequence-Based Metagenome: Cloning, Expression, Purification and Characterization. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Shao, J.Y. New preparation for oral administration of digestive enzyme. Lactase complex microcapsules. Biomater. Artif. Cells Immobil. Biotechnol. 1993, 21, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, K.i.; Yoshioka, S.; Kojima, S. Physical Stability and Protein Stability of Freeze-Dried Cakes During Storage at Elevated Temperatures. Pharm. Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 11, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenos, K.; Kyroudis, S.; Anagnostidis, A.; Papastathopoulos, P. Treatment of lactose intolerance with exogenous beta-D-galactosidase in pellet form. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 1998, 23, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Nail, S.L. Effect of process conditions on recovery of protein activity after freezing and freeze-drying. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1998, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchu, S.; Forbes, R.T.; York, P.; Petrén, S.; Nyqvist, H.; Camber, O. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inhibits spray-drying-induced inactivation of β-galactosidase. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, N.; Ohkura, R.; Miyazaki, S.; Uno, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Attwood, D. Thermally reversible xyloglucan gels as vehicles for oral drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 181, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aso, Y.; Yoshioka, S.; Nakai, Y.; Kojima, S. Thermally controlled protein release from gelatin-dextran hydrogels. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1999, 55, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikal-Cleland, K.A.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N.; Amidon, G.L.; Carpenter, J.F. Protein denaturation during freezing and thawing in phosphate buffer systems: Monomeric and tetrameric beta-galactosidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 384, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.S.; Ihm, M.R.; Ahn, J. Microencapsulation of β-galactosidase with fatty acid esters. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, N.S. Cationic liposomes as in vivo delivery vehicles. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, S.; Tajima, S.; Aso, Y.; Kojima, S. Inactivation and Aggregation of β-Galactosidase in Lyophilized Formulation Described by Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts Stretched Exponential Function. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.C.; Jeon, B.J.; Ahn, J.; Kwak, H.S. In vitro study of microencapsulated isoflavone and β-galactosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2582–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.E.; Wu, F.; Jin, T. Microencapsulation of protein-loaded polysaccharide particles within poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres using S/O/W: Characterization and release studies. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2009, 20, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giteau, A.; Venier-Julienne, M.C.; Marchal, S.; Courthaudon, J.L.; Sergent, M.; Montero-Menei, C.; Verdier, J.M.; Benoit, J.P. Reversible protein precipitation to ensure stability during encapsulation within PLGA microspheres. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 70, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genina, N.; Räikkönen, H.; Heinämäki, J.; Veski, P.; Yliruusi, J. Nano-coating of β-galactosidase onto the surface of lactose by using an ultrasound-assisted technique. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, S.; Walsh, G. A novel acid-stable, acid-active beta-galactosidase potentially suited to the alleviation of lactose intolerance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzinger, G.; Wang, X.; Wirth, M.; Gabor, F. Targeted PLGA microparticles as a novel concept for treatment of lactose intolerance. J. Control. Release 2010, 147, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Yuan, W.; Zhao, H.; Jin, T. Sustained-release polylactide-co-glycolide microspheres loaded with pre-formulated protein polysaccharide nanoparticles. Micro Nano Lett. 2011, 6, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuchar, N.; Sunasee, R.; Ishihara, K.; Thundat, T.; Narain, R. Degradable thermoresponsive nanogels for protein encapsulation and controlled release. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F.; Santos, L.; Alves, A. Microencapsulation with chitosan by spray drying for industry applications—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Z.; Su, J.; Wei, L.; Yuan, W.; Jin, T. Development of dextran nanoparticles for stabilizing delicate proteins. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnashar, M.M.; Kahil, T. Biopolymeric formulations for biocatalysis and biomedical applications. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 418097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.J.; Zhang, X.T.; Sheng, Y. Enteric-coated capsule containing β-galactosidase-loaded polylactic acid nanocapsules: Enzyme stability and milk lactose hydrolysis under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 81, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevinho, B.N.; Ramos, I.; Rocha, F. Effect of the pH in the formation of β-galactosidase microparticles produced by a spray-drying process. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 78, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facin, B.R.; Moret, B.; Baretta, D.; Belfiore, L.A.; Paulino, A.T. Immobilization and controlled release of β-galactosidase from chitosan-grafted hydrogels. Food Chem. 2015, 179, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, I.; Nagy, Z.K.; Vass, P.; Fehér, C.; Barta, Z.; Vigh, T.; Sóti, P.L.; Harasztos, A.H.; Pataki, H.; Balogh, A.; et al. Stable formulation of protein-type drug in electrospun polymeric fiber followed by tableting and scaling-up experiments. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2015, 26, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.P.; Zhang, R.J.; Chen, L.; McClements, D.J. Encapsulation of lactase (β-galactosidase) into κ-carrageenan-based hydrogel beads: Impact of environmental conditions on enzyme activity. Food Chem. 2016, 200, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Montemagno, C.; Choi, H.J. Smart Microparticles with a pH-responsive Macropore for Targeted Oral Drug Delivery. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffano-Schiffo, M.V.; Castro-Giraldez, M.; Fito, P.J.; Santagapita, P.R. Encapsulation of lactase in Ca(II)-alginate beads: Effect of stabilizers and drying methods. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffano-Schiffo, M.V.; Aguirre Calvo, T.R.; Castro-Giraldez, M.; Fito, P.J.; Santagapita, P.R. Alginate Beads Containing Lactase: Stability and Microstructure. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayun, B.; Sun, C.; Kumar, A.; Montemagno, C.; Choi, H.J. Facile fabrication of microparticles with pH-responsive macropores for small intestine targeted drug formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 128, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Visser, J.C.; Klever, J.S.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Frijlink, H.W.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Orodispersible films based on blends of trehalose and pullulan for protein delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 133, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiäinen, T.; Räikkönen, H.; Kolu, A.M.; Peltoniemi, M.; Juppo, A. Comparison of melibiose and trehalose as stabilising excipients for spray-dried β-galactosidase formulations. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 543, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.; Valldeperas, M.; Dhayal, S.K.; Barauskas, J.; Dicko, C.; Nylander, T. Immobilisation of β-galactosidase within a lipid sponge phase: Structure, stability and kinetics characterisation. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 21291–21301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayun, B.; Choi, H.J. Halloysite nanotube-embedded microparticles for intestine-targeted co-delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 579, 119152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.L.; McClements, D.J. Recent advances in encapsulation, protection, and oral delivery of bioactive proteins and peptides using colloidal systems. Molecules 2020, 25, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwalter, C.E.; Pagels, R.F.; Hejazi, A.N.; Gordon, A.G.R.; Thompson, A.L.; Prud’homme, R.K. Polymeric Nanocarrier Formulations of Biologics Using Inverse Flash NanoPrecipitation. AAPS J. 2020, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.; Trevisan, M.G.; Garcia, J.S. Β-galactosidase Encapsulated in Carrageenan, Pectin and Carrageenan/Pectin: Comparative Study, Stability and Controlled Release. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2020, 92, e20180609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.W.; Pickett, M.J.; Kuosmanen, J.L.P.; Ishida, K.; Madani, W.A.M.; White, G.N.; Jenkins, J.; Feig, V.R.; Jimenez, M.; Lopes, A.; et al. Drinkable, liquid in situ-forming and tough hydrogels for gastrointestinal therapeutics. Nat. Mater. 2022, 23, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, M.; Sántha, K.; Kállai-Szabó, B.; Pencz, K.M.; Ludányi, K.; Kállai-Szabó, N.; Antal, I. Development and Dissolution Study of a β-Galactosidase Containing Drinking Straw. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Gabold, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Hartschuh, A.; Chiesa, E.; Genta, I.; Ried, C.L.; Merdan, T.; et al. Microfluidic mixing as platform technology for production of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with different macromolecules. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 188, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, Y.N.; Tobón, A.C.; Mesa, M. Optimization of the synthesis process of β-galactosidase/carboxymethylchitosan-silica biocatalyst powders, stabilized with lyoprotectants for potential dietary applications. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobón, Y.N.F.; Herrera-Ramírez, A.; Cardona-Galeano, W.; Mesa, M. Correlations between in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of β-galactosidase/carboxymethylchitosan-silica dosage powder and its physicochemical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Liu, R.J.; Kim, A.S.; Cyr, N.N.; Boehlein, S.K.; Resende, M.F.R., Jr.; Savin, D.A.; Bailey, L.S.; Sumerlin, B.S.; Hudalla, G.A. Sweet corn phytoglycogen dendrimers as a lyoprotectant for dry-state protein storage. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2024, 112, 2026–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile-Gutiérrez, I.; Iglesias, S.; Acosta, N.; Revuelta, J. Chitosan-based oral hydrogel formulations of β-galactosidase to improve enzyme supplementation therapy for lactose intolerance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 127755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, S.; Hasan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Richards, S.J.; Dietrich, B.; Wallace, M.; Tang, Q.; Smith, A.J.; Gibson, M.I.; Adams, D.J. Mechanical release of homogenous proteins from supramolecular gels. Nature 2024, 631, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talley, K.; Alexov, E. On the pH-optimum of activity and stability of proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2010, 78, 2699–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P.; Ananthanarayan, L. Enzyme stability and stabilization—Aqueous and non-aqueous environment. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Aili, T.; Yang, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Bai, L.; Lv, X.; Huang, X. Dual signal light detection of beta-lactoglobulin based on a porous silicon bragg mirror. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 204, 114035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Song, Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, W.; Ren, T.; Ma, A.; Li, S.; Jia, Y. Characterization of an epilactose-producing cellobiose 2-epimerase from Clostridium sp. TW13 and reutilization of waste milk. Food Chem. 2025, 480, 143948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, R.; de Castro, M.J.; de Lamas, C.; Picáns, R.; Couce, M.L. Effects of Prebiotic and Probiotic Supplementation on Lactase Deficiency and Lactose Intolerance: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Ryu, H.J.; Bhatt, R.R. The neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1451–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to lactase enzyme and breaking down lactose (ID 1697, 1818) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheskey, P.J.; Cook, W.G.; Cable, C.G. American Pharmacists Assoscition. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 8th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK; American Pharmacists Assoscition: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, A.; Kecskés, B.A.; Filipszki, G.; Farkas, D.; Tóth, B.; Antal, I.; Kállai-Szabó, N. Fabrication and Evaluation of Isomalt-Based Microfibers as Drug Carrier Systems. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagenende, V.; Yap, M.G.S.; Trout, B.L. Mechanisms of Protein Stabilization and Prevention of Protein Aggregation by Glycerol. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11084–11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Rana, D.; Patel, M.; Bajwa, N.; Prasad, R.; Vora, L.K. Nanoparticle Therapeutics in Clinical Perspective: Classification, Marketed Products, and Regulatory Landscape. Small 2025, 21, e2502315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Levitt, M.D.; Taylor, B.C.; MacDonald, R.; Shamliyan, T.A.; Kane, R.L.; Wilt, T.J. Systematic review: Effective management strategies for lactose intolerance. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Dungen, M.W.; Boer, R.; Wilms, L.C.; Efimova, Y.; Abbas, H.E. The safety of a Kluyveromyces lactis strain lineage for enzyme production. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 126, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Fitaihi, R.; Abdelhakim, H.E. Advances in formulation and manufacturing strategies for the delivery of therapeutic proteins and peptides in orally disintegrating dosage forms. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 182, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Duan, X. A Novel Thermal-Activated β-Galactosidase from Bacillus aryabhattai GEL-09 for Lactose Hydrolysis in Milk. Foods 2022, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.A.; Khedr, M.; Abdelraof, M. Activation of LacZ gene in Escherichia coli DH5α via α-complementation mechanism for β-galactosidase production and its biochemical characterizations. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Brand Name | Manufacturer | Dosage Form | Dose (FCC) | Regulatory Classification | Source of Enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactase | Strathmann (Hamburg, Germany) | chewable tablet | 2900 | medicine | A. oryzae |

| Coli comfort | Brand Up Pharma (Újlengyel, Hungary) | drops | 143/drop (12 drops) | dietary supplement | A. oryzae, K. lactis |

| Lactase comfort | Brand Up Pharma (Újlengyel, Hungary) | drops | 2500/drop (1 drop) | dietary supplement | no data |

| Co-lactase | Magnapharm Hungary (Budapest, Hungary) | drops | 225/drop (2–4 drops) | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| Shake & Wait | Scitec Kft. (Budaörs, Hungary) | powder | 2000 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| Antilact | BioTech USA Kft. (Budapest, Hungary) | capsule | 4500 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Laktáz Enzim | Scitec Kft. (Budaörs, Hungary) | capsule | 5000 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| Laktáz enzim | Herbapharma Kft (Budapest, Hungary) | capsule | 5000 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Starlife Laktáz Enzim Star | Starlife s.r.o (Lidicka, Czechia) | capsule | 5200 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| Mill & Joy | TEVA Zrt. (Debrecen, Hungary) | tablet | 4500 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Laktáz Enzim | Nutriversum Kft. (Budapest, Hungary) | tablet | 5000 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Biocom4You Laktáz Enzim | Ökonet Európa Kft. (Dabas, Hungary) | tablet | 5000 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| LIVSANE Laktáz | PXG Pharma GmbH (Mannheim, Germany) | tablet | 6000 | dietary supplement | no data |

| JutaVit Laktáz | JuvaPharma Kft. (Felsőpakony, Hungary) | tablet | 6500 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| Innolact | InnoPharm Kft. (Budapest, Hungary) | filmtablet | 6000 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Fermentált Laktáz | Natur Tanya Hungary Kft. (Budapest, Hungary) | chewable tablet | 4500 | dietary supplement | A. oryzae |

| LactaMed | Rubenza Kft. (Budapest, Hungary) | chewable tablet | 5000 | dietary supplement | no data |

| Dosage Form | Purpose of Innovation | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide gel | Microcapsules with semipermeable enteric soluble materials | This complex microencapsulated lactase retained over 65% of its activity after 2 h of simulation in gastric juice. | Wang et al. (1993) [66] |

| Freeze-dried cake | Additive-based stabilization for increase enzyme stability during storage | Various excipients provide effective stabilization for β-galactosidase during storage. | Izutsu et al. (1994) [67] |

| Calcium-alginate based pellet | Immobilization with sodium alginate and calcium chloride in pellets to maintain protein stability and biological activity | The new pellet formulation effectively reduced symptoms and improved glucose absorption. | Xenos et al. (1998) [68] |

| Freeze-dried powder | Optimizing freeze-drying parameters without protectants to preserve protein activity after lyophilization | Protein activity preservation can be significantly improved by optimizing freezing and drying conditions, even without protectants. | Jiang & Nail (1998) [69] |

| Polymethylmethacrylate microparticles | Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inhibits spray-drying-induced inactivation of β-galactosidase | Cyclodextrins can be useful for stabilizing excipients in the preparation of spray-dried protein pharmaceuticals. | Branchu et al. (1999) [70] |

| Thermo-sensitive xyloglucan-based gel | Thermally reversible gelation for sustained release | Xyloglucan-based gel may be suitable for sustained oral release. | Kawasaki et al. (1999) [71] |

| Gelatin–dextran-based hydrogel | Sol–gel transition, glycidyl methacrylate-dextran crosslinking via gamma irradiation for temperature-sensitive protein release | Sol–gel transition enables temperature-sensitive protein release; glycidyl methacrylate substitution and gelatin concentration influence the release profile. | Aso et al. (1999) [72] |

| Freeze-dried powder | Fast vs. slow cooling/heating process, sodium phosphate vs. potassium phosphate buffers to increase protein stability during freeze–thaw cycles | pH changes and cooling rate significantly affect protein activity recovery. | Pikal-Cleland et al. (2000) [73] |

| Microcapsules with different coatings | Microencapsulation for enzyme stability and controlled release | Propylene glycol monostearate and medium-chain triglyceride coatings effectively protect the enzyme and regulate release. | Kwak et al. (2001) [74] |

| Casein matrix microcapsules | Encapsulation with casein via emulsion polymerization, pH-sensitive release for targeted release | Microcapsules protected lactase from gastric acid and ensured controlled intestinal release. | Templeton et al. (2003) [75] |

| Lyophilized product | Polymers: polyvinyl alcohol, methylcellulose to increase stability, reducing aggregation | The Kohlrausch–Williams–Watts model describes aggregation/inactivation kinetics well; storage time can be extrapolated. | Yoshioka et al., (2003) [76] |

| Microencapsulated formulation | Microencapsulation with glycol monostearate and medium-chain triglyceride coating to enzyme release in small intestine | Microencapsulated β-galactosidase is effectively released in the gastro-intestinal tract. | Kim et al. (2006) [77] |

| Polysaccharide microparticles | Alginate core, poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid shell (microencapsulation) for controlled release and enhanced protein stability | The double encapsulation system improved encapsulation efficiency and preserved activity. | Yuan et al. (2009) [78] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid microsphere | Reversible protein precipitation (with glycofurol and NaCl) for preserving protein stability during encapsulation | Reversible precipitation allowed enzyme preservation within poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid microspheres without inactivation. | Giteau et al. (2008) [79] |

| Nano-coated lactose particle | Ultrasonically produced enzyme nanocoating for enzyme protection | Nanocoating remained stable for 1 month, with no loss of enzyme activity. | Genina et al. (2010) [80] |

| Two-phase capsule: gastric- and intestinal-active enzyme combination | Combination of enzymes from different sources and enteric coating for enhanced stability | The capsule hydrolyzed 3.5 times more lactose than the commercial product. | O’Connell & Walsh, (2010) [81] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid microparticles | Surface wheat germ agglutinin attachment, cross-linker: hexamethylene diamine and 1-ethyl-3(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide | Targeted poly(lactic-co-glycolic) microparticles may be effective for long-term lactase supplementation. | Ratzinger et al. (2010) [82] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid microspheres | S/O/W emulsion, dextran-based core for controlled protein release, burst release reduction | The new microsphere production method reduces initial burst release and improves bioactivity. | Ren et al. (2011) [83] |

| Thermo-responsive nanogel (core cross-linked micelles) | Reversible Addition–Fragmentation chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization, thermo-sensitive degradable core, poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) shell for protein encapsulation and controlled release | Nanogels prepared by RAFT are stable and biocompatible and effectively regulate protein release with temperature changes. | Bhuchar et al. (2012) [84] |

| Alginate–chitosan microparticles | Producing microparticles with chitosan, by a spray-drying process, for industrial applications | Microparticles effectively protect proteins from gastric acid and promote controlled intestinal release. | Estevinho et al. (2013) [85] |

| Dextran nanoparticles | Ionotropic gelation and drying for enzyme protection in the gastro-intestinal tract | Dextran-based formulation protected the enzyme in acidic environments and maintained its activity. | Wu et al., (2013) [86] |

| Gel discs (carrageenan + chitosan/polyethyleneimine) | Glutaraldehyde covalent immobilization for biotech and medical use | Different polyelectrolyte complex systems have varying effects on stability and kinetics. | Elnashar & Kahil (2014) [87] |

| Enteric-coated capsule | pH-sensitive polymer coating for enzyme protection from gastric acid | Enteric-coated capsules effectively protect the enzyme in the stomach and ensure its activity in the intestine. | He et al. (2014) [88] |

| Chitosan microcapsules | The influence of pH in the microencapsulation process, using a modified chitosan | The microencapsulated formulation was obtained at pH 6, being more than four times higher than the formulations produced with different pH levels. | Estevinho et al. (2015) [89] |

| Hydrogel (chitosan grafted) | Immobilization, controlled release for lactose-free food production | Chitosan-based grafted hydrogels are suitable for effective β-galactosidase immobilization and controlled release, reusable with stable activity. | Facin et al. (2015) [90] |

| Electrospun polymer fiber | Polyvinyl alcohol/polycaprolactone blend, addition of cryoprotectant (trehalose) for maintaining protein stability and biological activity | Electrospun fibers effectively preserve enzyme activity even when stored at room temperature. | Wagner et al. (2015) [91] |

| κ-carrageenan-based hydrogel beads | K+ ion stabilization, physical encapsulation for increased enzyme stability | Encapsulation increases activity and stability, but leakage may occur. | Zhang et al. (2016) [92] |

| pH-sensitive microparticles | Macroporous pH-sensitive Eudragit microparticle for targeted intestine release | The smart, pH-sensitive system provided enhanced protection and targeted drug release. | Kumar et al. (2017) [93] |

| Alginate–Ca(II) beads | Trehalose, arabic and guar gum additives for maintain protein stability and biological activity | Trehalose and guar gum improved stability; excipients influenced structure and heat stability. | Traffano-Schiffo et al. (2017) [94] Traffano-Schiffo et al. (2017) [95] |

| pH-sensitive, macroporous microparticle | Macropore formation, pH-sensitive response for small intestine targeting | The newly developed macroporous microparticles can be effectively used for directing proteins to the intestinal tract. | Homayun et al. (2018) [96] |

| Orodispersible films | Protein loaded orodispersible films (ODFs), based on blends of trehalose/pullulan by air- and freeze-drying. | The stability of β-galactosidase increased with increasing trehalose/pullulan ratios. | Tian et al. (2018) [97] |

| Powdered bulk granules | Spray-drying parameter optimization for more stable protein formulation | The precise optimization of drying conditions improves protein powder stability and solubility. | Lipiäinen et al. (2018) [98] |

| Lipid sponge | Formulation of a matrix for controlled delivery, to achieve a high protein load and to ensure high activity of the protein | The encapsulated β-galactosidase maintained its activity for a significantly longer time compared to the free solution at the same temperature. | Gilbert et al. (2019) [99] |

| Halloysite nanotube-embedded microparticle | Nanotube embedding, pH-sensitive for small intestine targeting | Halloysite nanotube systems provide significant stability benefits for oral protein administration. | Homayun et al. (2020) [100] |

| Colloidal systems (emulsions, liposomes, microgels) | Encapsulation, food-grade colloidal delivery systems for oral protein delivery and stabilization | Colloidal systems may be effective for the stable and targeted oral delivery of bioactive peptides and proteins. | Perry & McClements (2020) [101] |

| Nanocarrier (polymeric nanocarrier) | Polymer-based nanoparticle for improving enzyme stability | The formulation enhanced enzyme stability and bioavailability for oral administration. | Markwalter et al. (2020) [102] |

| Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) microgel | Polymer matrix, pH-sensitive gelation for maintain enzyme activity and targeted release | CMC-based microgel improved enzyme stability and efficacy. | Silva et al. (2020) [103] |

| In situ gel-forming system (liquid dosage) | pH-sensitive gel-forming system for improving enzyme stability | The system provided excellent stability and biological activity for oral enzyme delivery. | Liu et al. (2022) [104] |

| Drinking straw filled with pellets | Novel oral administration method for children, elderly and those with dysphagia | This is an innovative child-friendly dosage form with powdered enzyme formulation in a straw. | Király et al. (2022) [105] |

| Nanocarriers | Nano-sized drug delivery systems provide protection, stability, and controlled release of proteins | Microfluidic mixing is an affordable and efficient platform for delivery of biological macromolecules. | Greco et al. (2023) [106] |

| Carboxymethyl chitosan– silica powder (biocatalyst) | One-pot silica gel route, maltose as lyoprotectant for enzyme stabilization | The biocatalyst showed high activity in the stomach (96%) and intestine (63%), is stable for 12 months and is non-cytotoxic. | Franco Tobón et al. (2023) [107] Franco Tobón et al. (2024) [108] |

| Lyophilized protein-liquid mixture with phytoglycogen | Addition of phyto glycogen dendrimers (PG1–PG16), focus on PG13 for protein stabilization during lyophilization | PG13 dendrimers are effective lyoprotectants and cake-forming agents for various proteins. | Park et al. (2024) [109] |

| Chitosan–alginate–pectin polymer gel | Polymer matrix formation and thermal stabilization for stabilization and bioavailability improvement | The combined gel system enhanced stability and enabled delivery in various environments. | Fraile-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) [110] |

| Polymer film | Mechanically triggered release for enzyme stabilization and controlled release locally | Mechanical activation enables homogeneous and controlled drug release, which is promising for local applications. | Bianco et al. (2024) [111] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Király, M.; Barna, Á.T.; Kállai-Szabó, N.; Kiss, B.D.; Antal, I.; Ludányi, K. Advances in β-Galactosidase Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Enzyme Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1538. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121538

Király M, Barna ÁT, Kállai-Szabó N, Kiss BD, Antal I, Ludányi K. Advances in β-Galactosidase Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Enzyme Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1538. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121538

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirály, Márton, Ádám Tibor Barna, Nikolett Kállai-Szabó, Borbála Dalmadiné Kiss, István Antal, and Krisztina Ludányi. 2025. "Advances in β-Galactosidase Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Enzyme Delivery Systems" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1538. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121538

APA StyleKirály, M., Barna, Á. T., Kállai-Szabó, N., Kiss, B. D., Antal, I., & Ludányi, K. (2025). Advances in β-Galactosidase Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Enzyme Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1538. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121538