Classifying Effluxable Versus Non-Effluxable Compounds Using a Permeability Threshold Based on Fundamental Energy Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

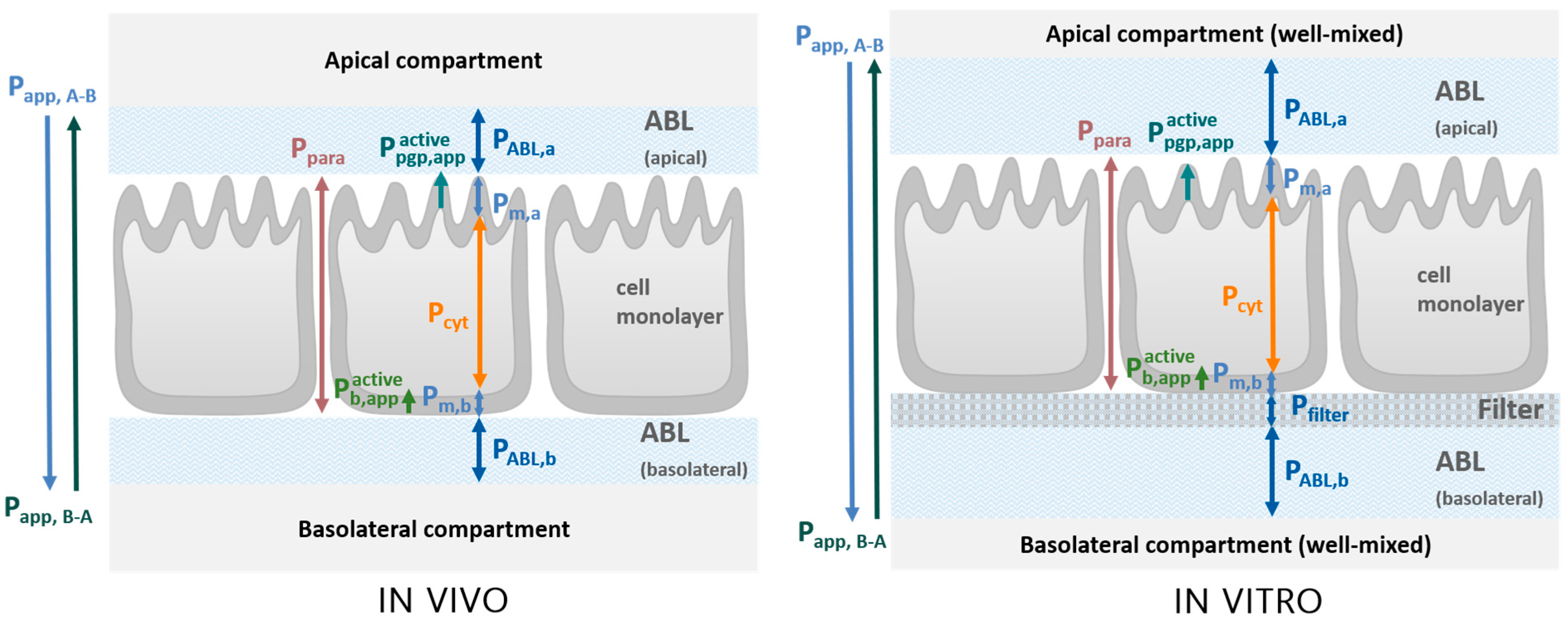

2.1. Transport Model

2.2. Maximal Active Transport Flux and Borderline Compounds

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Determination of Passive Membrane Permeability Pm

3.1.1. In Silico Prediction of Pm Using UFZ-LSERD/COSMO-RS

3.1.2. Experimental Determination of Pm with Bidirectional MDCK Assays

3.1.3. Experimental Determination of Pm with PAMPA and SDM

3.2. Analysis of ER Data

3.2.1. Evaluation of ER Data from Literature

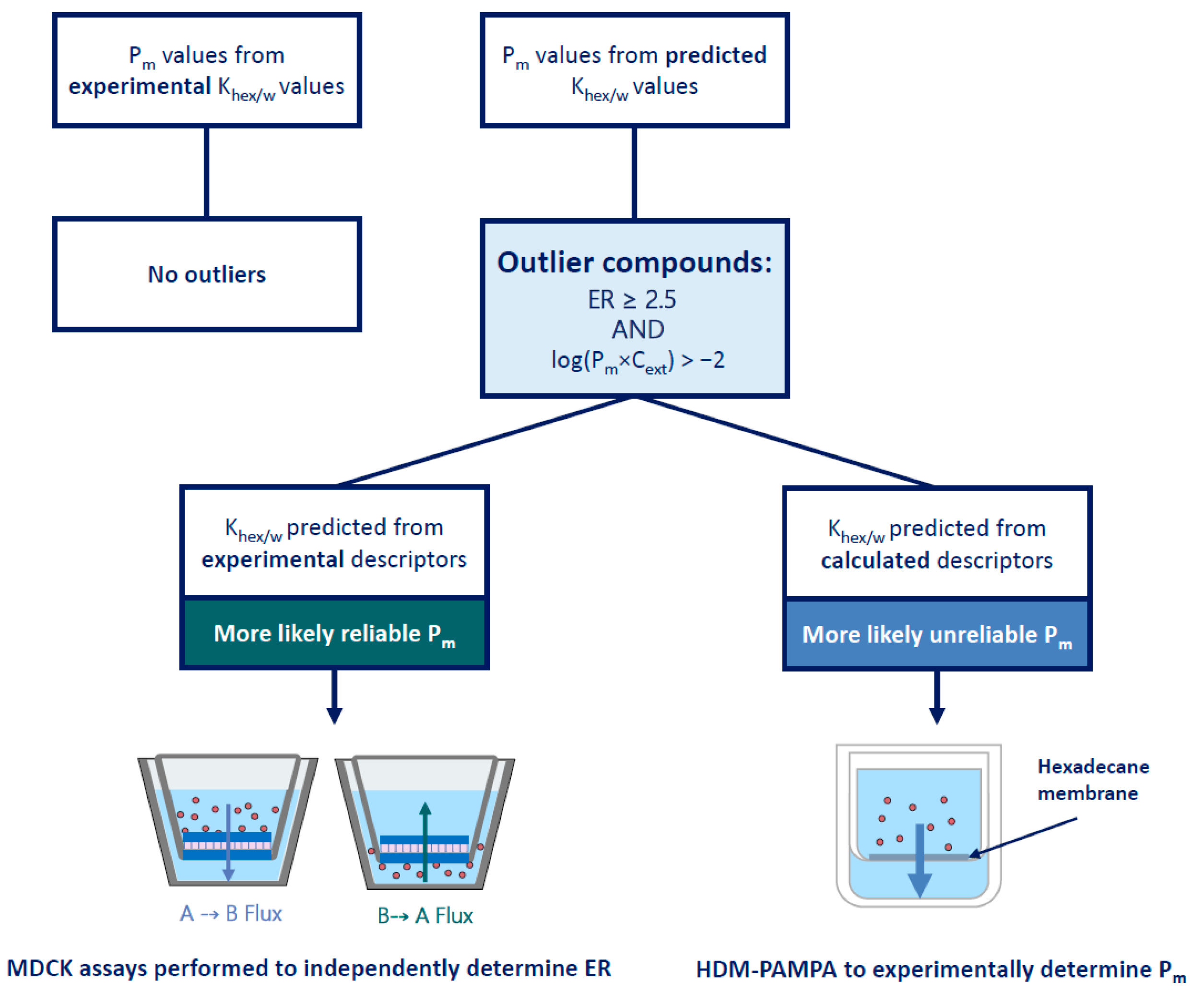

3.2.2. Re-Determining the ER of Outlier Compounds with Bidirectional MDCK Assays

Chemicals and Reagents

Cells and Cell Culture

Bidirectional MDCK Assays

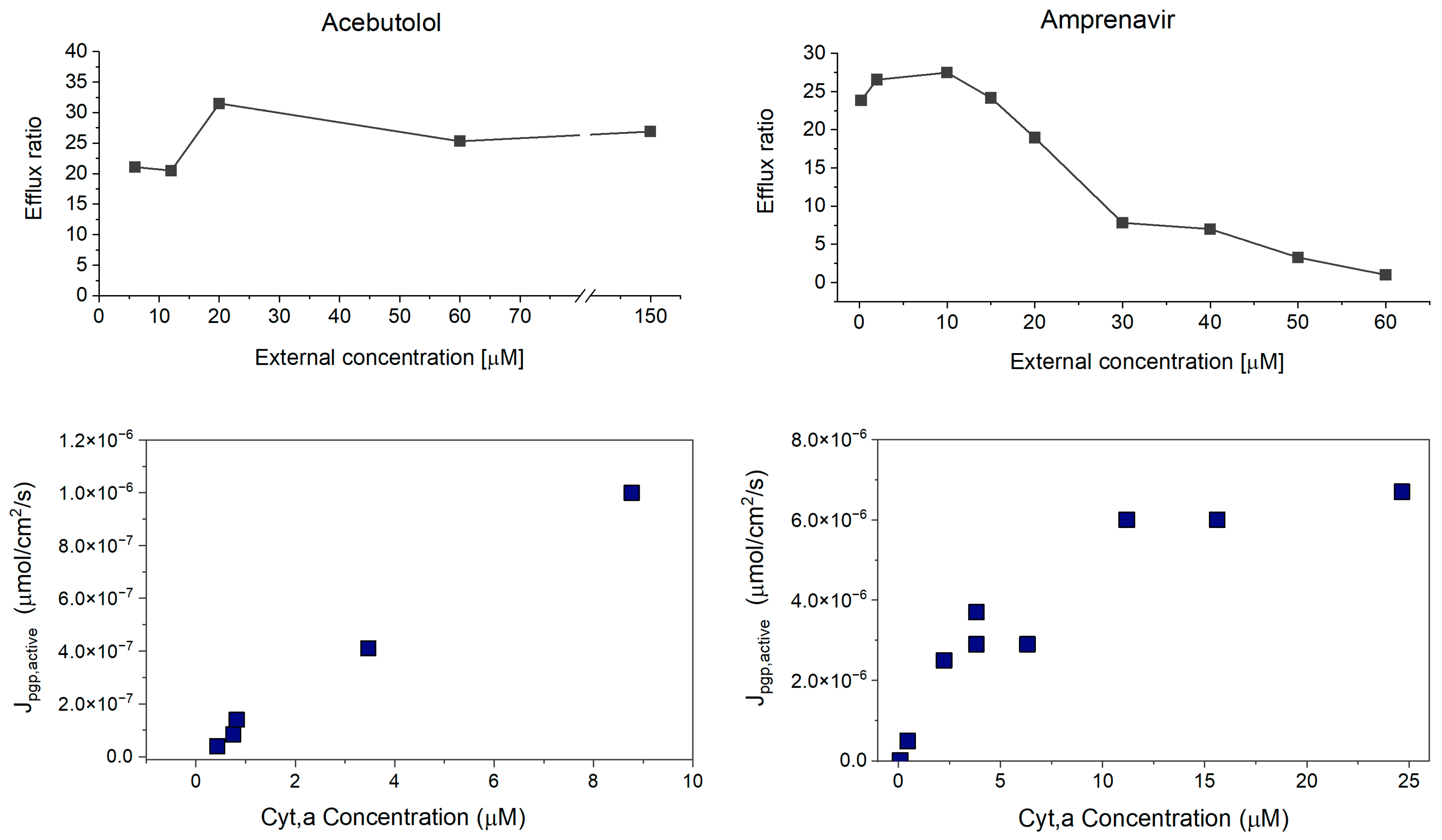

3.2.3. Concentration-Dependent MDCK Assays for Borderline Compounds

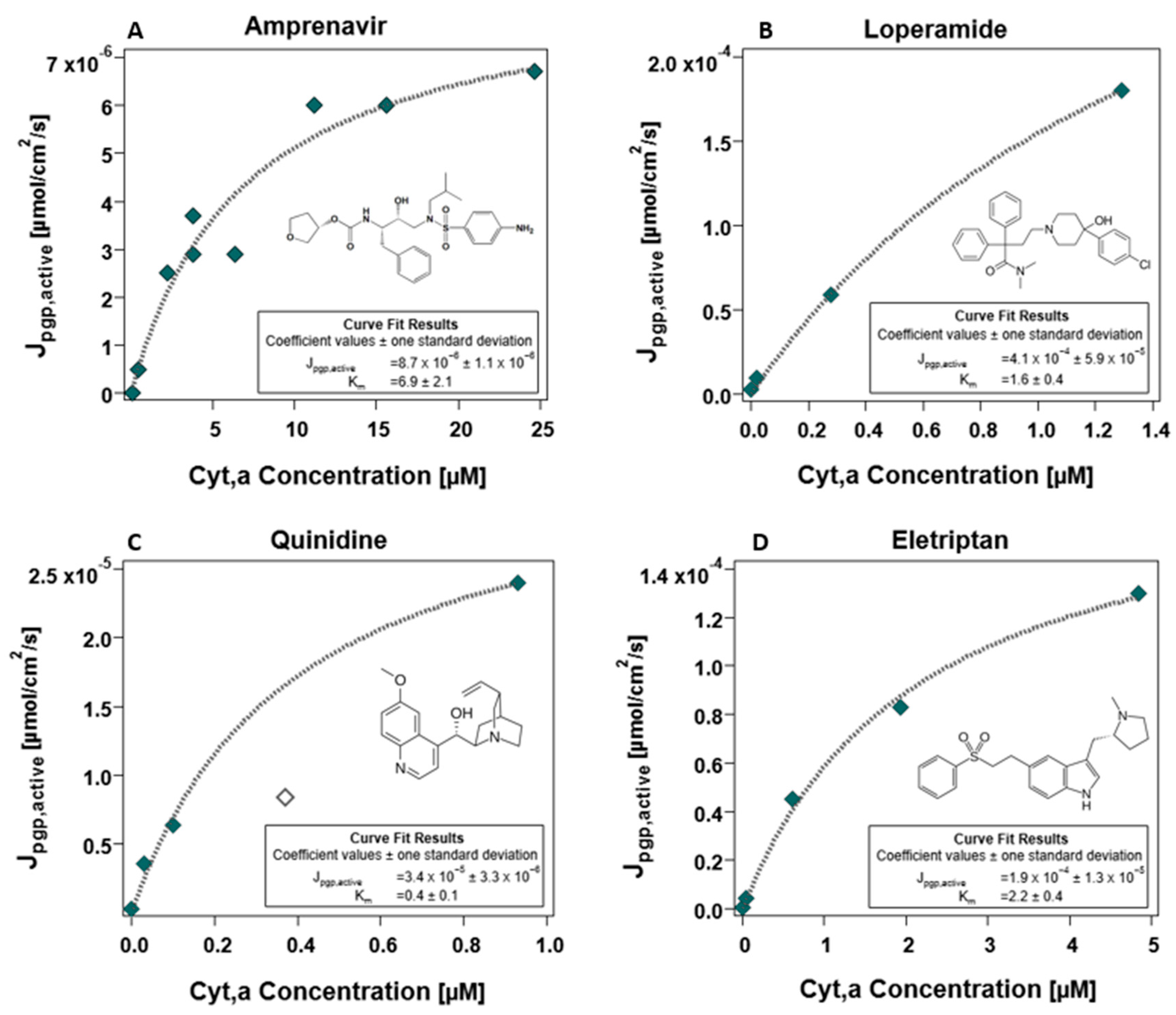

3.2.4. Determination of and Maximal Flux Jpgp,active

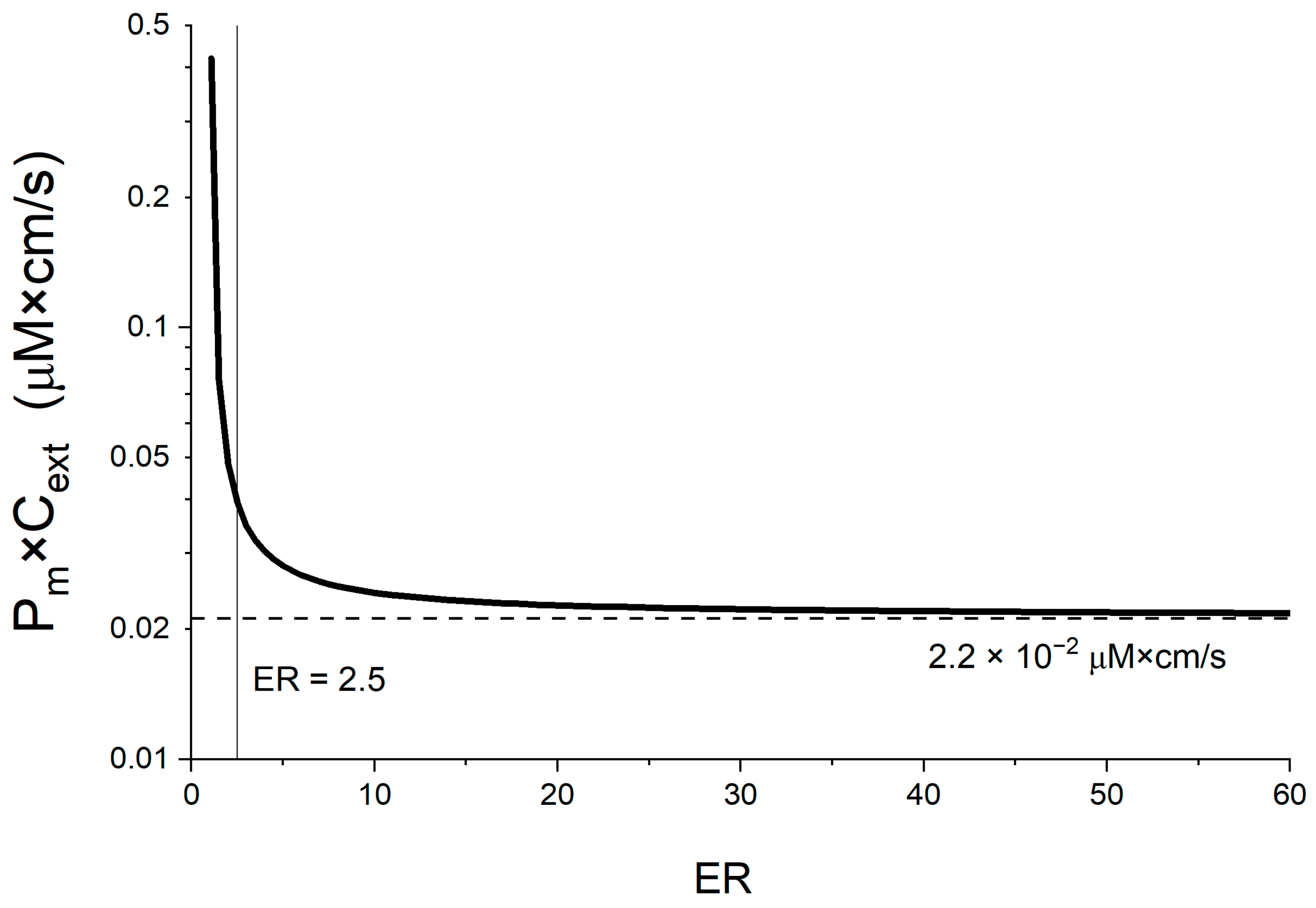

3.2.5. Linking the Maximal Flux Value with a Membrane Permeability Threshold

4. Results and Discussion

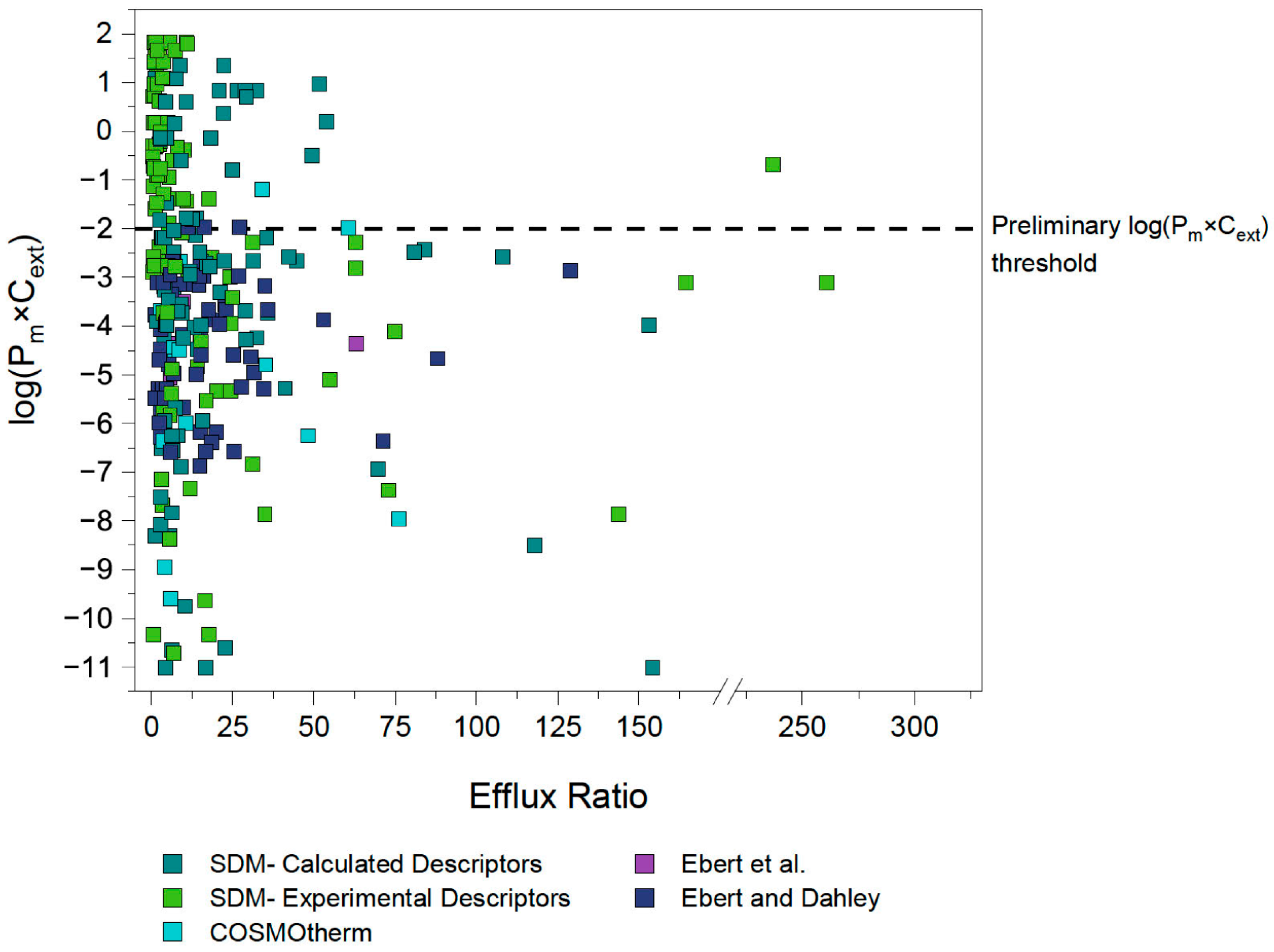

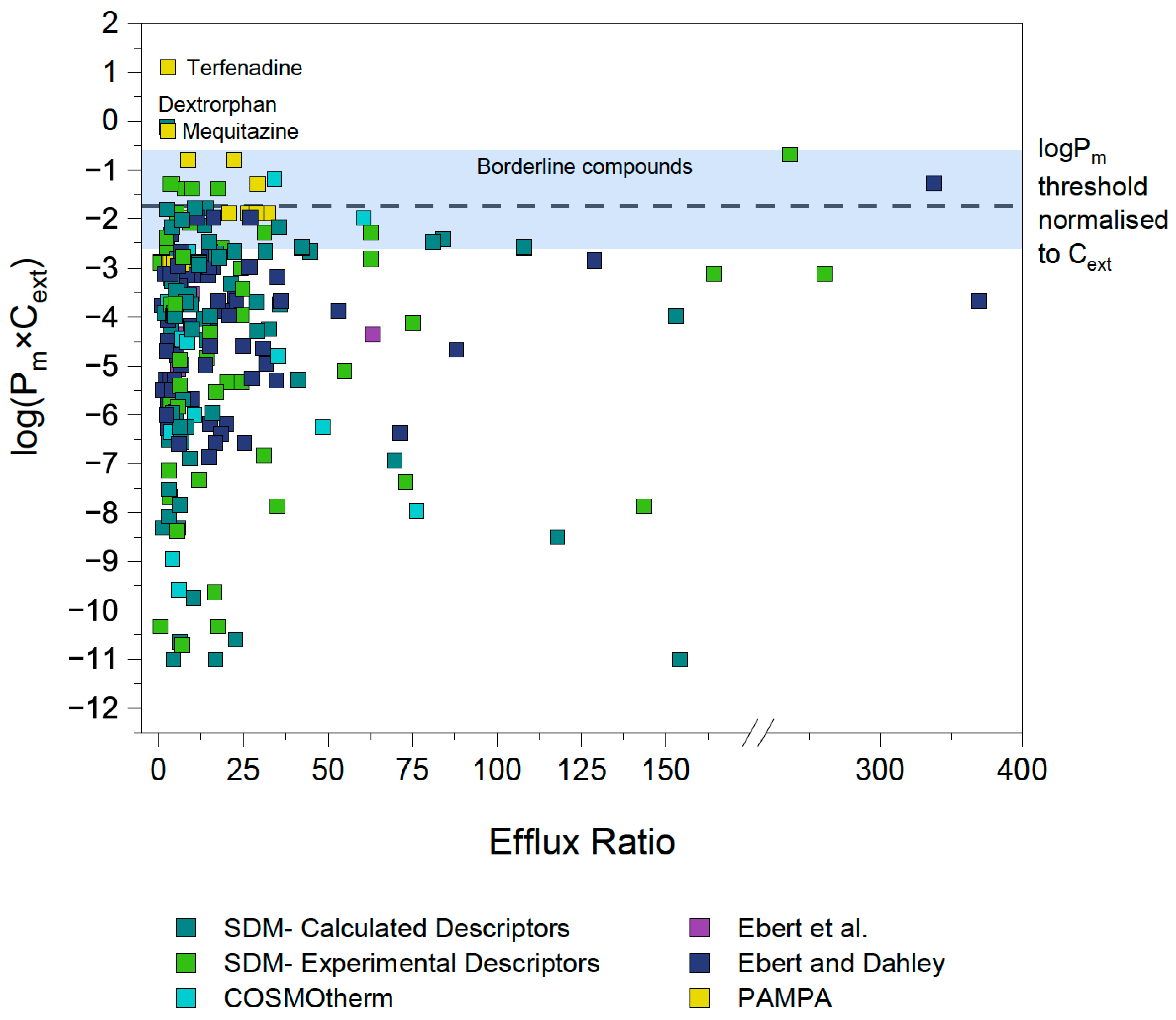

4.1. First Estimation of Pm×Cext Limit

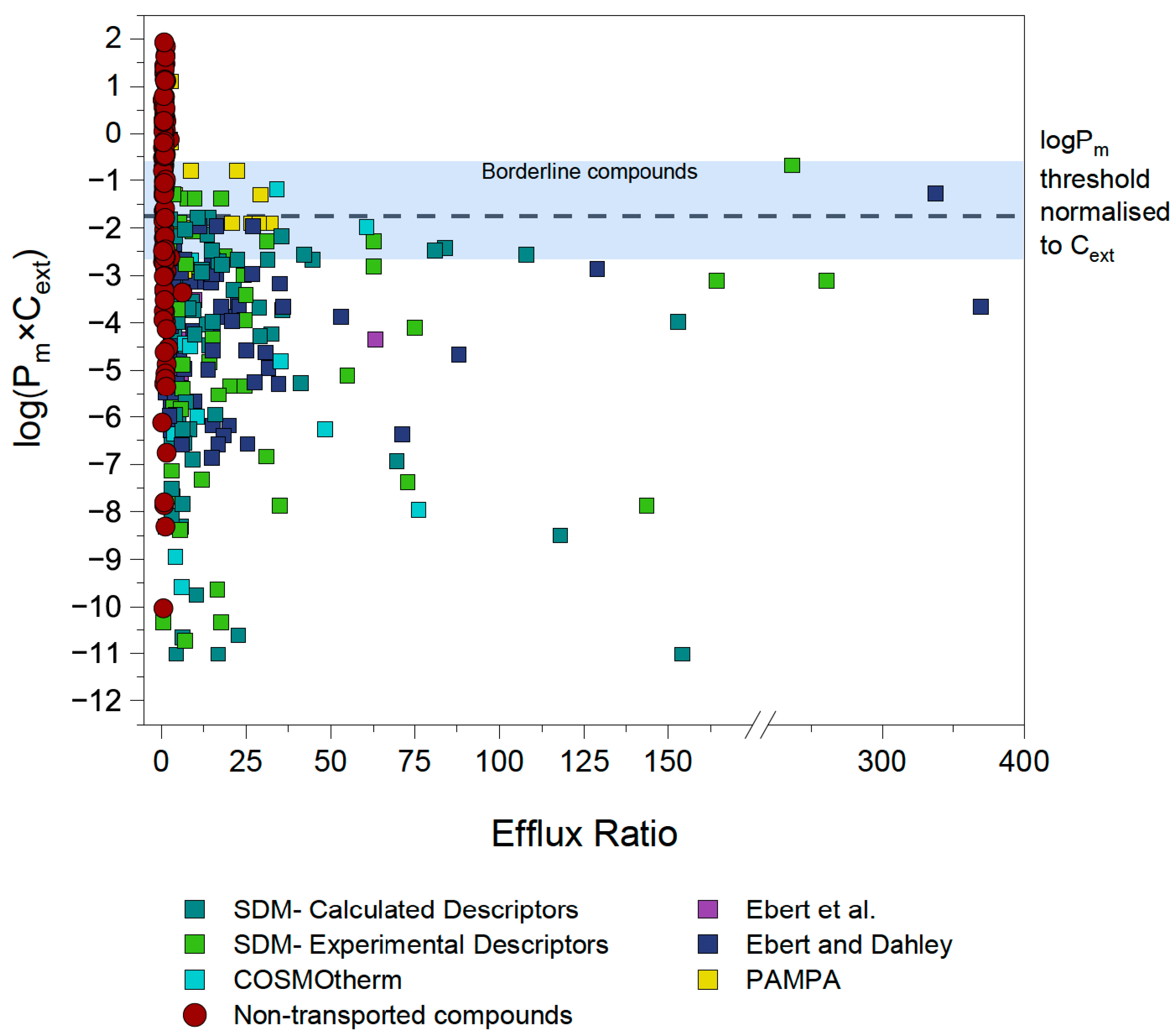

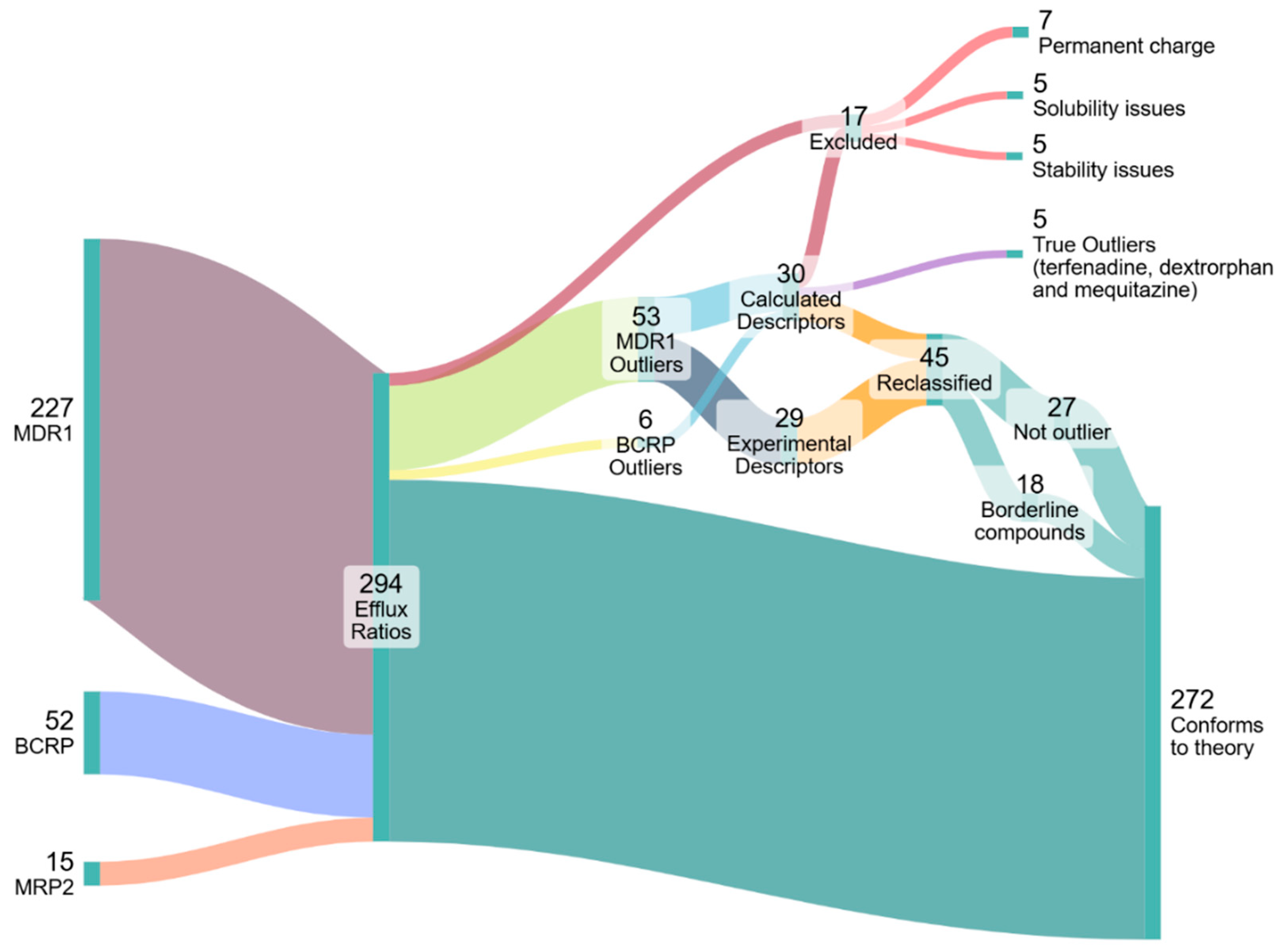

4.2. Identification and Investigation of Outliers

4.3. Outlier Reclassification

4.4. Concentration-Dependent Investigation of Borderline Compounds

4.5. Empirical Determination of the Energy Limit

4.6. Linking a Passive Membrane Permeability Threshold to the Energy Limit

4.7. Sensitivity Analysis of Pm Threshold

4.8. Re-Evaluation of Literature Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galetin, A.; Brouwer, K.L.R.; Tweedie, D.; Yoshida, K.; Sjöstedt, N.; Aleksunes, L.; Chu, X.; Evers, R.; Hafey, M.J.; Lai, Y.; et al. Membrane transporters in drug development and as determinants of precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvale, A.; Abdul Hamid, A.A.; Abd Halim, K.B.; Che, H. P-glycoprotein: New Insights into Structure, Physiological Function, Regulation and Alterations in Disease, in Heliyon; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sharom, F.J. ABC multidrug transporters: Structure, function and role in chemoresistance. Pharmacogenomics 2007, 9, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Li, B.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Kankala, R.K. Overcoming Cancer Multi-drug Resistance (MDR): Reasons, mechanisms, nanotherapeutic solutions, and challenges. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lai, J.; Wang, J.; Xia, F. Mechanism of multidrug resistance to chemotherapy mediated by P-glycoprotein (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2023, 63, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demel, M.A.; Krämer, O.; Ettmayer, P.; Haaksma, E.E.J.; Ecker, G.F. Predicting ligand interactions with ABC transporters in ADME. Chem. Biodivers. 2009, 6, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghray, D.; Zhang, Q. Inhibit or Evade Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein in Cancer Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5108–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Sun, H.; Hou, T. ADMET evaluation in drug discovery. 13. Development of in silico prediction models for p-glycoprotein substrates. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liang, H.; Bender, A.; Glen, R.C.; Yan, A. P-glycoprotein substrate models using support vector machines based on a comprehensive data set. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Hou, T. Computational models for predicting substrates or inhibitors of P-glycoprotein. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, A.; Yamashita, T.; Kanaya, S.; Kosugi, Y. Ensemble Machine Learning Approaches Based on Molecular Descriptors and Graph Convolutional Networks for Predicting the Efflux Activities of MDR1 and BCRP Transporters. AAPS J. 2023, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Wang, S.; Lange, U.E.W.; Oellien, F.; Riniker, S. Combining Machine Learning and Molecular Dynamics to Predict P-Glycoprotein Substrates. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 4730–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seelig, A. A general pattern for substrate recognition by P-glycoprotein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 251, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didziapetris, R.; Japertas, P.; Avdeef, A.; Petrauskas, A. Classification analysis of P-glycoprotein substrate specificity. J. Drug Target. 2003, 11, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gombar, V.K.; Polli, J.W.; Humphreys, J.E.; Wring, S.A.; Serabjit-Singh, C.S. Predicting P-Glycoprotein Substrates by a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Model. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 4, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, C.; Vellido, A. Understanding predictions of drug profiles using explainable machine learning models. BioData Min. 2024, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Kang, Y.; Hou, T. A multimodal contrastive learning framework for predicting P-glycoprotein substrates and inhibitors. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, T.K.; Hailu, S.; Feng, S.; Graham, R.; Gukasyan, H.J. Eyes on Lipinski’s Rule of Five: A New “Rule of Thumb” for Physicochemical Design Space of Ophthalmic Drugs. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 38, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Kwon, S.H.; Zhou, X.; Fuller, C.; Wang, X.; Vadgama, J.; Wu, Y. Overcoming Challenges in Small-Molecule Drug Bioavailability: A Review of Key Factors and Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahley, C.; Böckmann, T.; Ebert, A.; Goss, K.U. Predicting the intrinsic membrane permeability of Caco-2/MDCK cells by the solubility-diffusion model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 195, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, S.; Goss, K.-U.; Ebert, A. The pH-dependence of efflux ratios determined with bidirectional transport assays across cellular monolayers. Int. J. Pharm. X 2024, 8, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Schmoldt, A. Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of more than 800 drugs and other xenobiotics. Pharmazie 2003, 58, 447–474. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, A.; Hannesschlaeger, C.; Goss, K.U.; Pohl, P. Passive Permeability of Planar Lipid Bilayers to Organic Anions. Biophys. J. 2018, 115, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, B.I.; Abagyan, R.; Embry, M.; Klüver, N.; Redman, A.D.; Zarfl, C.; Parkerton, T.F. Recommendations for Improving Methods and Models for Aquatic Hazard Assessment of Ionizable Organic Chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2020, 39, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACD Percepta, version 2020.1.2; Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc. (ACD/Labs): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. Available online: https://www.acdlabs.com (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ebert, A.; Dahley, C. Can membrane permeability of zwitterionic compounds be predicted by the solubility-diffusion model? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 199, 106819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palay, S.L.; Karlin, L.J. An Electron Microscopic Study of the Intestinal Villus II. The Pathway of Fat Absorption. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1959, 5, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butor, C.; Davoust, J. Apical to Basolateral Surface Area Ratio and Polarity of MDCK Cells Grown on Different Supports. Exp. Cell Res. 1992, 203, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittermann, K.; Goss, K.U. Predicting apparent passive permeability of Caco-2 and MDCK cell-monolayers: A mechanistic model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UFZ-LSER. UFZ-LSER Database v4.0; Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ: Leipzig, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, F.; Klamt, A. Fast Solvent Screening via Quantum Chemistry: COSMO-RS Approach. AIChE J. 2002, 48, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.; Dahley, C.; Goss, K.U. Pitfalls in evaluating permeability experiments with Caco-2/MDCK cell monolayers. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 194, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahley, C.; Goss, K.U.; Ebert, A. Predicting Caco-2/MDCK Intrinsic Membrane Permeability from HDM-PAMPA-Derived Hexadecane/Water Partition Coefficients. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 214, 107280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, T.T.; Chandrasekaran, R.Y.; Hou, X.; Troutman, M.D.; Verhoest, P.R.; Villalobos, A.; Will, Y. Defining desirable central nervous system drug space through the alignment of molecular properties, in vitro ADME, and safety attributes. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010, 1, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, E.; Malhotra, B.; Bungay, P.J.; Webster, R.; Fenner, K.S.; Kempshall, S.; LaPerle, J.L.; Michel, M.C.; Kay, G.G. A comprehensive non-clinical evaluation of the CNS penetration potential of antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of overactive bladder. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 72, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Mills, J.B.; Davidson, R.E.; Mireles, R.J.; Janiszewski, J.S.; Troutman, M.D.; de Morais, S.M. In vitro P-glycoprotein assays to predict the in vivo interactions of P-glycoprotein with drugs in the central nervous system. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troutman, M.D.; Thakker, D.R. Novel Experimental Parameters to Quantify the Modulation of Absorptive and Secretory Transport of Compounds by P-Glycoprotein in Cell Culture Models of Intestinal Epithelium. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1210–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar Doan, K.M.; Humphreys, J.E.; Webster, L.O.; Wring, S.A.; Shampine, L.J.; Serabjit-Singh, C.J.; Adkison, K.K.; Polli, J.W. Passive permeability and P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux differentiate central nervous system (CNS) and non-CNS marketed drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polli, J.W.; Wring, S.A.; Humphreys, J.E.; Huang, L.; Morgan, J.B.; Webster, L.O.; Serabjit-Singh, C.S. Rational Use of in Vitro P-glycoprotein Assays in Drug Discovery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 299, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellinger, É.; Veszelka, S.; Tóth, A.E.; Walter, F.; Kittel, Á.; Laura, M.; Tihanyi, K.; Háda, V.; Nakagawa, S.; Dinh, T.; et al. Comparison of brain capillary endothelial cell-based and epithelial (MDCK-MDR1, Caco-2, and VB-Caco-2) cell-based surrogate blood-brain barrier penetration models. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 82, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Rager, J.D.; Weinstein, K.; Kardos, P.S.; Dobson, G.L.; Li, J.; Hidalgo, I.J. Evaluation of the MDR-MDCK cell line as a permeability screen for the blood-brain barrier. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 288, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, S.; Reali, V.; Misiano, P.; Dondio, G.; Bigogno, C. Evaluation of in vitro brain penetration: Optimized PAMPA and MDCKII-MDR1 assay comparison. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 345, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, T.; Dobson, G.G.; Shingaki, T.; Kungu, T.; Hidalgo, I.J. Assessment of the first and second generation antihistamines brain penetration and role of P-glycoprotein. Pharm. Res. 2007, 24, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hanson, E.; Watson, J.W.; Lee, J.S. P-Glycoprotein limits the brain penetration of nonsedating but not sedating H1-antagonists. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Okochi, H.; Benet, L.Z. Is Ciprofloxacin a Substrate of P-glycoprotein? Arch. Drug Inf. 2011, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertz, M.; Harrison, A.; Houston, J.B.; Galetin, A. Prediction of human intestinal first-pass metabolism of 25 CYP3A substrates from in vitro clearance and permeability data. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Bahadduri, P.M.; Polli, J.E.; Swaan, P.W.; Ekins, S. Rapid identification of P-glycoprotein substrates and inhibitors. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1976–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, U.G.; Dorani, H.; Karlsson, J.; Fritsch, H.; Hoffmann, K.-J.; Olsson, L.; Sarich, T.C.; Wall, U.; Schützer, K.-M. Influence of erythromycin on the pharmacokinetics of ximelagatran may involve inhibition of P-glycoprotein-mediated excretion. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, M.E.; Podila, L.; Ely, D.; Almeida, I. Functional assessment of multiple p-glycoprotein (P-gp) probe substrates: Influence of cell line and modulator concentration on P-gp activity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005, 33, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Grimm, S. ATP-dependent transport of rosuvastatin in membrane vesicles expressing breast cancer resistance protein. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.; Benet, L.Z.; Huang, Y.; Storpirtis, S. Comparison of bidirectional lamivudine and zidovudine transport using MDCK, MDCK-MDR1, and Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 4413–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Pal, D.; Shah, S.J.; Kwatra, D.; Paturi, K.D.; Mitra, A.K. Effect of HEPES buffer on the uptake and transport of p-glycoprotein substrates and large neutral amino acids. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ouyang, H.; Yang, J.Z.; Borchardt, R.T. Bidirectional Transport of Rhodamine 123 and Hoechst 33342, Fluorescence Probes of the Binding Sites on P-glycoprotein, across MDCK-MDR1 Cell Monolayers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Okochi, H.; Benet, L.Z.; Zhai, S.-D. Sotalol permeability in cultured-cell, rat intestine, and PAMPA system. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Mireles, R.J.; Campbell, S.D.; Lin, J.; Mills, J.B.; Xu, J.J.; Smolarek, T.A. Differential interaction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors with ABCB1, ABCC2, and OATP1B1. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005, 33, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegler, C.; Gazit, M.; Issa, K.; Subramaniam, S.; Artursson, P.; Karlgren, M. Expanding the Efflux In Vitro Assay Toolbox: A CRISPR-Cas9 Edited MDCK Cell Line with Human BCRP and Completely Lacking Canine MDR1. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoff, I.; Karlgren, M.; Backlund, M.; Lindström, A.-C.; Gaugaz, F.Z.; Matsson, P.; Artursson, P. Complete Knockout of Endogenous Mdr1 (Abcb1) in MDCK Cells by CRISPR-Cas9. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Gao, S.; Yin, T.; Liu, W.; Wang, F.; Hu, M.; Liu, Z. The role of efflux transporters on the transport of highly toxic aconitine, mesaconitine, hypaconitine, and their hydrolysates, as determined in cultured Caco-2 and transfected MDCKII cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 216, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muenster, U.; Grieshop, B.; Ickenroth, K.; Gnoth, M.J. Characterization of substrates and inhibitors for the in vitro assessment of bcrp mediated drug-drug interactions. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Li, S.; Xie, L.; Zhong, W.; Lv, J.; Zhang, X.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, Z. Are capecitabine and the active metabolite 5-FU CNS penetrable to treat breast cancer brain metastasis? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; West, M.; Patel, N.C.; Wager, T.; Hou, X.; Johnson, J.; Tremaine, L.; Liras, J. Validation of Human MDR1-MDCK and BCRP-MDCK Cell Lines to Improve the Prediction of Brain Penetration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkavilli, R.; Jadhav, G.; Vangala, S. Evaluation of Drug Transport in MDCKII-Wild Type, MDCKII-MDR1, MDCKII-BCRP and Caco-2 Cell Lines. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Shaik, N.M.; Chen, C.; Yang, Z.; Elmquist, W.F. P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein influence brain distribution of dasatinib. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Davidson, R.; Smith, A.; Pereira, D.; Zhao, S.; Soglia, J.; Gebhard, D.; de Morais, S.; Duignan, D.B. A 96-well efflux assay to identify ABCG2 substrates using a stably transfected MDCK II cell line. Mol. Pharm. 2006, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, A.; Portmann, R.; Cascais, A.-C.; Bader, U.; Walter, I.; Ullah, M.; Funk, C. The need for human breast cancer resistance protein substrate and inhibition evaluation in drug discovery and development: Why, when, and how? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 1466–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, S.; de Vries, N.A.; Buckle, T.; Bolijn, M.J.; van Eijndhoven, M.A.J.; Beijnen, J.H.; Mazzanti, R.; van Tellingen, O.; Schellens, J.H.M. Effect of the ATP-binding cassette drug transporters ABCB1, ABCG2, and ABCC2 on erlotinib hydrochloride (Tarceva) disposition in in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies employing Bcrp1-/-/Mdr1a/1b-/- (triple-knockout) and wild-type mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2280–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polli, J.W.; Humphreys, J.E.; Harmon, K.A.; Castellino, S.; O’Mara, M.J.; Olson, K.L.; John-Williams, L.S.; Koch, K.M.; Serabjit-Singh, C.J. The role of efflux and uptake transporters in N-{3-chloro-4-[(3- fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-6-[5-({[2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]amino}methyl)-2-furyl] -4-quinazolinamine (GW572016, lapatinib) disposition and drug interactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahringer, A.; Delzer, J.; Fricker, G. A fluorescence-based in vitro assay for drug interactions with breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2). Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 72, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.Y.; Okochi, H.; Huang, Y.; Benet, L.Z. Multiple transporters affect the disposition of atorvastatin and its two active hydroxy metabolites: Application of in vitro and ex situ systems. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Westerhoff, A.M.; Gé, L.G.; Carlsen, K.L.; Pedersen, M.D.L.; Nielsen, C.U. MRP2-mediated transport of etoposide in MDCKII MRP2 cells is unaffected by commonly used non-ionic surfactants. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 56, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.T.; Chhatta, A.A.; van Tellingen, O.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. MRP2 (ABCC2) transports taxanes and confers paclitaxel resistance and both processes are stimulated by probenecid. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 116, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Xu, C.; O’Neal, S.; Bi, H.; Huang, M.; Zheng, W.; Zeng, S. Roles of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein in transporting para-aminosalicylic acid and its N-acetylated metabolite in mice brain. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; van de Wetering, K.; van de Steeg, E.; Wagenaar, E.; Vens, C.; Schinkel, A.H. Species-dependent transport and modulation properties of human and mouse multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2/Mrp2, ABCC2/Abcc2). Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Agarwal, S.; Mandava, N.K.; Sheng, Y.; Mitra, A.K. Interaction of dipeptide prodrugs of saquinavir with multidrug resistance protein-2 (MRP-2): Evasion of MRP-2 mediated efflux. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 362, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.C.; Liu, A.; Knipp, G.; Sinko, P.J. Direct evidence that saquinavir is transported by multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1) and canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter (MRP2). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3456–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Horie, K.; Borchardt, R.T. Are MDCK Cells Transfected with the Human MRP2 Gene a Good Model of the Human Intestinal Mucosa? Pharm. Res. 2002, 19, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, S.; Ebert, A.; Goss, K.U. Effects of Aqueous Boundary Layers and Paracellular Transport on the Efflux Ratio as a Measure of Active Transport Across Cell Layers. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, J.D.; Takahashi, L.; Lockhart, K.; Cheong, J.; Tolan, J.W.; Selick, H.E.; Grove, J.R. MDCK (Madin-Darby canine kidney) cells: A tool for membrane permeability screening. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhoff, S.; Ungell, A.L.; Zamora, I.; Artursson, P. pH-Dependent Bidirectional Transport of Weakly Basic Drugs across Caco-2 Monolayers: Implications for Drug-Drug Interactions. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, A.T.; Mönkkönen, J.; Korjamo, T. Kinetics of cellular retention during caco-2 permeation experiments: Role of lysosomal sequestration and impact on permeability estimates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 328, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.-L.; Yang, L. Classification of substrates and inhibitors of P-glycoprotein using unsupervised machine learning approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubic, M.; Wagner, D.; Spahn-Langguth, H.; Bolger, M.B.; Langguth, P. In silico modeling of non-linear drug absorption for the P-gp substrate talinolol and of consequences for the resulting pharmacodynamic effect. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, T.; Broske, L.; Brisson, J.-M.; Uss, A.S.; Njoroge, F.G.; Morrison, R.A.; Cheng, K.-C. Permeability evaluation of peptidic HCV protease inhibitors in Caco-2 cells-correlation with in vivo absorption predicted in humans. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, A.T.; Korjamo, T.; Lepikkö, V.; Mönkkönen, J. Effects of experimental setup on the apparent concentration dependency of active efflux transport in in vitro cell permeation experiments. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, T.; Kitamura, S.; Kato, M.; Mitsui, T.; Shirasaka, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Sugiyama, Y. Model analysis of the concentration-dependent permeability of p-gp substrates. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirasaka, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Sakane, T.; Omatsu, H.; Moriya, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Sakaeda, T.; Okumura, K.; Langguth, P.; Yamashita, S. Induction of human P-glycoprotein in Caco-2 cells: Development of a highly sensitive assay system for P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 21, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddings, E.L.; Champagne, D.P.; Wu, M.H.; Laffin, J.M.; Thornton, T.M.; Valenca-Pereira, F.; Culp-Hill, R.; Fortner, K.A.; Romero, N.; East, J.; et al. Mitochondrial ATP fuels ABC transporter-mediated drug efflux in cancer chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.; Nicolaï, J.; Williamson, B. The role of the efflux transporter, P-glycoprotein, at the blood-brain barrier in drug discovery. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2023, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmina, A.B.; Kharitonova, E.V.; Gorina, Y.V.; Teplyashina, E.A.; Malinovskaya, N.A.; Khilazheva, E.D.; Mosyagina, A.I.; Morgun, A.V.; Shuvaev, A.N.; Salmin, V.V.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier and Neurovascular Unit In Vitro Models for Studying Mitochondria-Driven Molecular Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.; Goss, K.U. Blood-brain barrier permeability revisited: Predicting intrinsic passive BBB permeability using the Solubility-diffusion model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 215, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet, L.Z.; Broccatelli, F.; Oprea, T.I. BDDCS applied to over 900 drugs. AAPS J. 2011, 13, 519–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakova, E.V.; Li, S.; Elmquist, W.F.; Miller, D.W.; Alakhov, V.Y.; Kabanov, A.V. Mechanism of sensitization of MDR cancer cells by Pluronic block copolymers: Selective energy depletion. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 1987–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Seebacher, N.; Shi, H.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Novel strategies to prevent the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84559–84571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Aguanno, D.; Board, M.; Callaghan, R. Exploiting the metabolic energy demands of drug efflux pumps provides a strategy to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, M.; Ózsvári, B.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. High ATP Production Fuels Cancer Drug Resistance and Metastasis: Implications for Mitochondrial ATP Depletion Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 740720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S. Solute and macromolecule diffusion in cellular aqueous compartments. TRENDS Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeef, A. Leakiness and size exclusion of paracellular channels in cultured epithelial cell monolayers-interlaboratory comparison. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahley, C.; Goss, K.-U.; Ebert, A. Revisiting the pKa-Flux method for determining intrinsic membrane permeability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 191, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, L.J. Concerning the relationship between the strength of acids and their capacity to preserve neutrality. Am. J. Physiol. 1908, 21, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, K.A. Die Berechnung der Wasserstoffzahl des Blutes aus der freien und gebundenen Kohlensäure desselben, und die Sauerstoffbindung des Blutes als Funktion der Wasserstoffzahl. Biochem. Z. 1916, 78, 112–144. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, J.; Artursson, P. A method for the determination of cellular permeability coefficients and aqueous boundary layer thickness in monolayers of intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells grown in permeable filter chambers. Int. J. Pharm. 1991, 71, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, B.; Homolya, L.; Szakács, G.; Váradi, A. Human multidrug resistance ABCB and ABCG transporters: Participation in a chemoimmunity defense system. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 1179–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Grider, M.H. Physiology, Adenosine Triphosphate; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, R.M.; Balaban, R.S. Energy metabolism of renal cell lines, A6 and MDCK: Regulation by Na-K-ATPase. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 252, C225–C231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamholz, A.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. The quantified cell. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 3497–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianconi, E.; Piovesan, A.; Facchin, F.; Beraudi, A.; Casadei, R.; Frabetti, F.; Vitale, L.; Pelleri, M.C.; Tassani, S.; Piva, F.; et al. An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2013, 40, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eytan, G.D.; Regev, R.; Assaraf, Y.G. Functional Reconstitution of P-glycoprotein Reveals an Apparent Near Stoichiometric Drug Transport to ATP Hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 3172–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larisch, W.; Goss, K.-U. Calculating the first-order kinetics of three coupled, reversible processes. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2017, 28, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeef, A.; Artursson, P.; Neuhoff, S.; Lazorova, L.; Gråsjö, J.; Tavelin, S. Caco-2 permeability of weakly basic drugs predicted with the Double-Sink PAMPA pKaflux method. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 24, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.A.; Miniyar, P.B.; Patil, A.S.; Waghmare, R.U.; Patil, J.J.; Mohanraj, K. Separation, Identification and Characterization of Degradation Products of Erlotinib Hydrochloride Under ICH Recommended Stress Conditions by LC, LC-MS/TOF. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2014, 38, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budavari, S. (Ed.) The Merck Index—Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs and Biologicals; Merck and Co., Inc.: Rahway, NJ, USA, 1989; p. 557. [Google Scholar]

- Pailla, S.R.; Sampathi, S.; Junnuthula, V.; Maddukuri, S.; Dodoala, S.; Dyawanapelly, S. Brain-Targeted Intranasal Delivery of Zotepine Microemulsion: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Canada Inc. (2016, October 28). Product Monograph: Viracept® (Nelfinavir Mesylate). Available online: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00037024.PDF (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Popović, G.; Cakar, M.; Agbaba, D. Acid-base equilibria and solubility of loratadine and desloratadine in water and micellar media. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strel’tsov, S.A.; Grokhovskii, S.L.; Kudelina, I.A.; Grokhovskii, S.L.; Kudelina, I.A.; Oleinikov, V.A.; Zhuze, A.L. Interaction of Topotecan, DNA Topoisomerase I Inhibitor, with Double-Stranded Polydeoxyribonucleotides. 1. Topotecan Dimerization in Solution. Mol. Biol. 2001, 35, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotze, S.; Goss, K.-U.; Ebert, A. Classifying Effluxable Versus Non-Effluxable Compounds Using a Permeability Threshold Based on Fundamental Energy Constraints. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111455

Kotze S, Goss K-U, Ebert A. Classifying Effluxable Versus Non-Effluxable Compounds Using a Permeability Threshold Based on Fundamental Energy Constraints. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111455

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotze, Soné, Kai-Uwe Goss, and Andrea Ebert. 2025. "Classifying Effluxable Versus Non-Effluxable Compounds Using a Permeability Threshold Based on Fundamental Energy Constraints" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111455

APA StyleKotze, S., Goss, K.-U., & Ebert, A. (2025). Classifying Effluxable Versus Non-Effluxable Compounds Using a Permeability Threshold Based on Fundamental Energy Constraints. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111455