Colon-Specific Delivery of Probenecid Enhances Therapeutic Activity of the Uricosuric Agent Against Rat Colitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

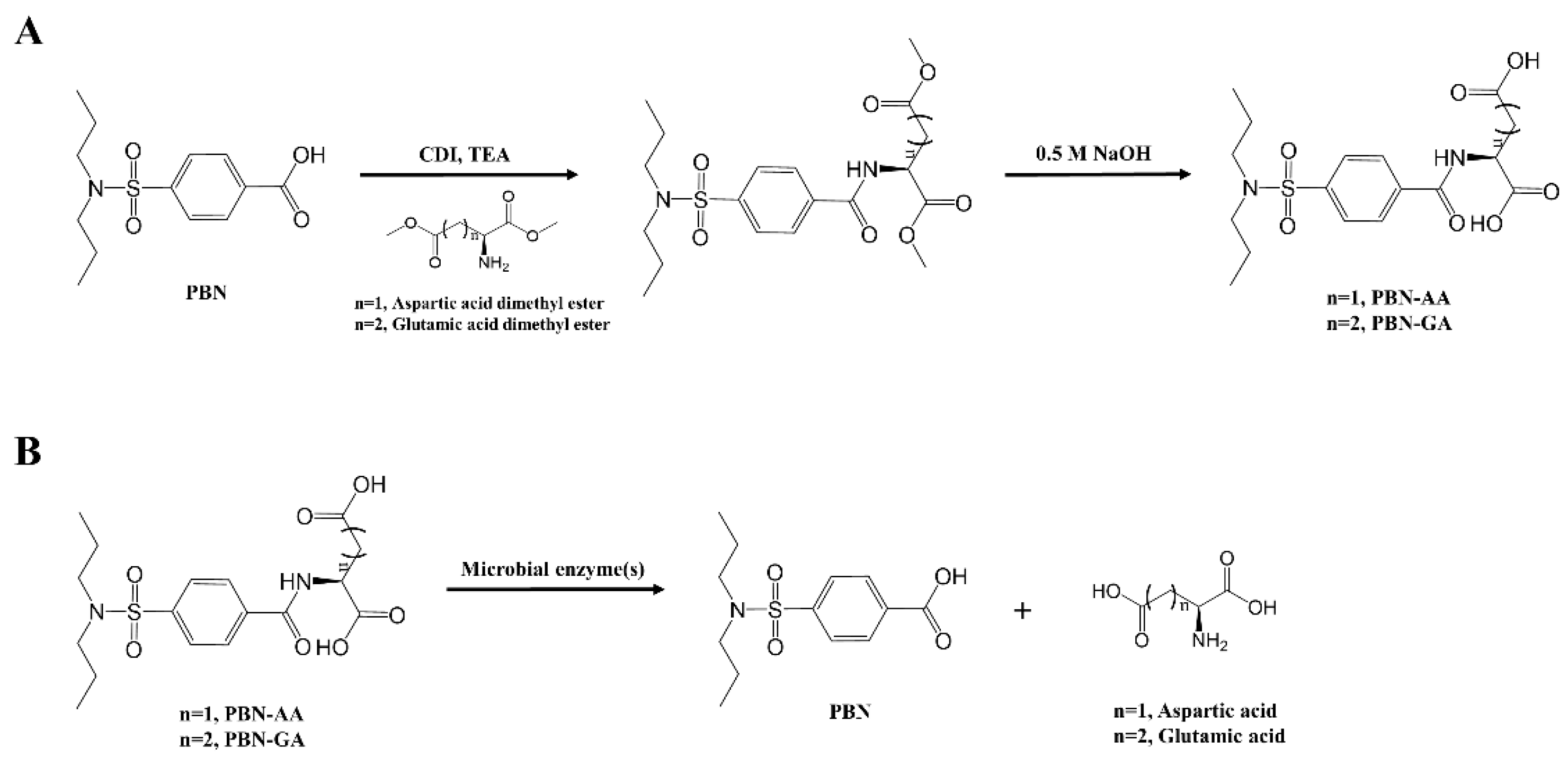

2.2. Synthesis of PBN Derivatives

2.3. HPLC Analysis

2.4. Distribution Coefficient and Chemical Stability

2.5. Cell Permeability Assay

2.6. Animals

2.7. Incubation of Drugs in the Contents of Rat Small Intestine and Cecum

2.8. Analysis of Drug Concentration in Blood and Cecum

2.9. DNBS-Induced Rat Colitis

2.10. Evaluation of Anticolitis Effects

2.11. Western Blot Analysis and ELISA for CINC-3

2.12. Data Analysis

3. Results

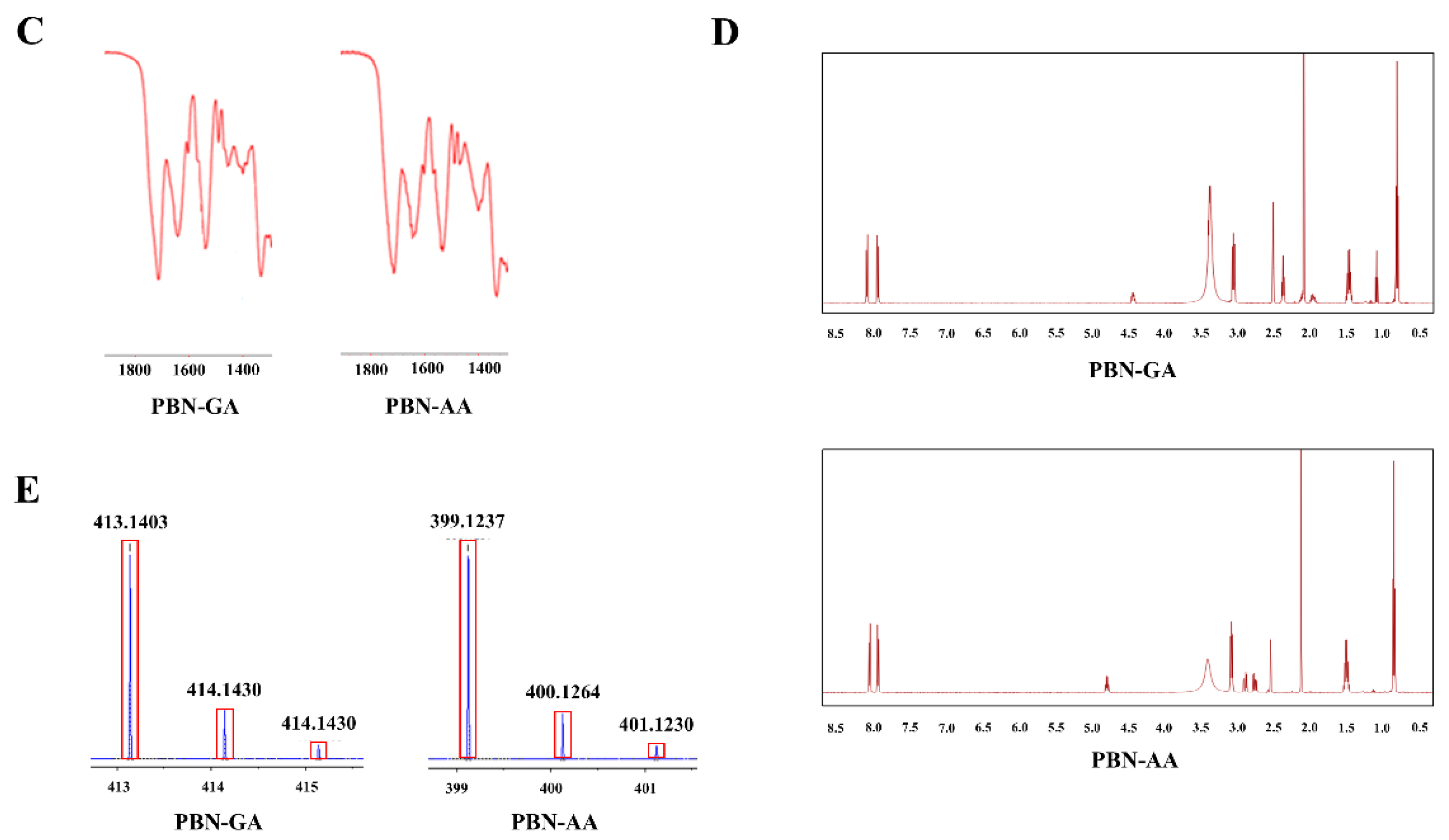

3.1. Synthesis of Probenecid Conjugated with Acidic Amino Acids

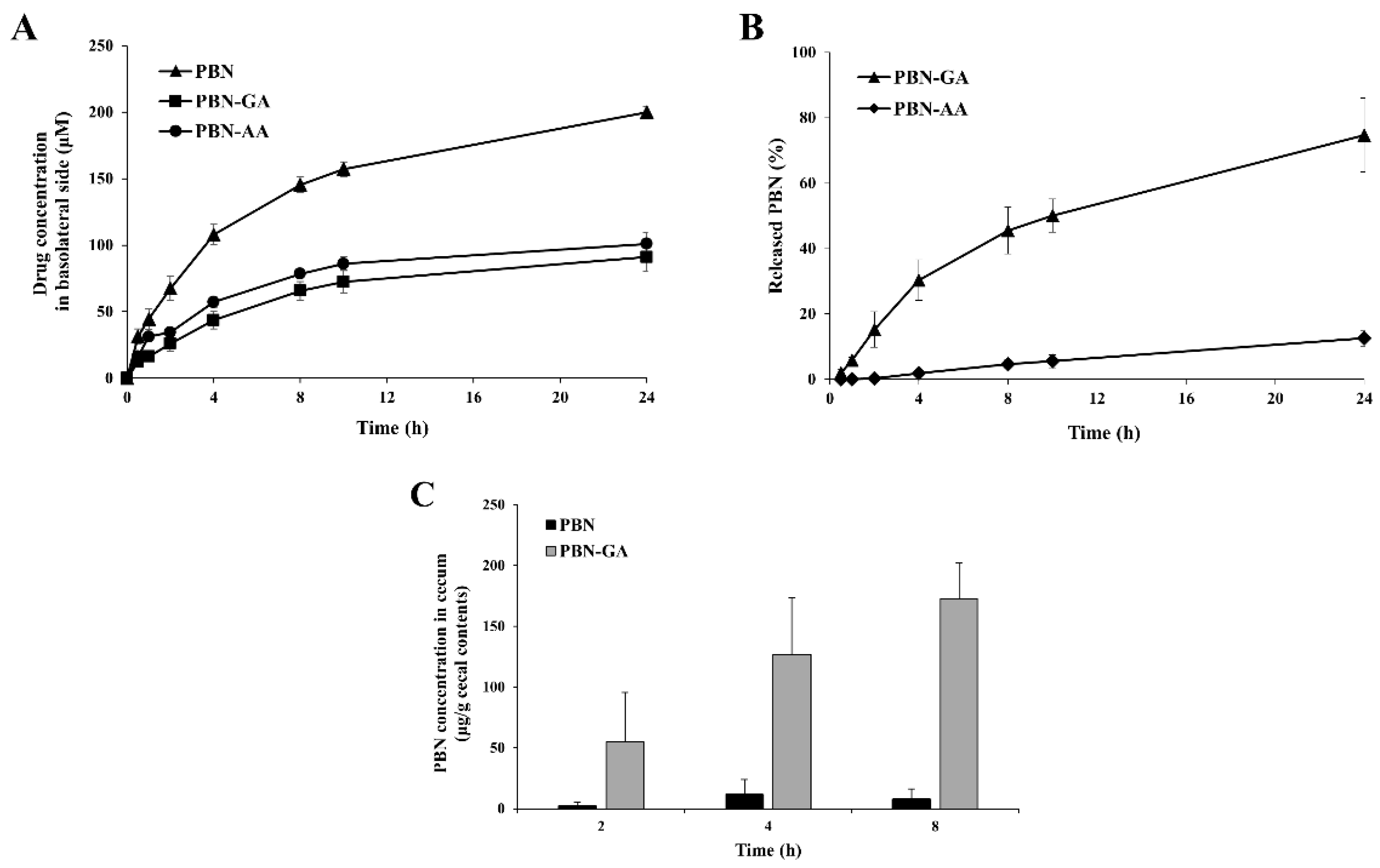

3.2. Colon Specificity of PBN Conjugated with Acidic Amino Acids

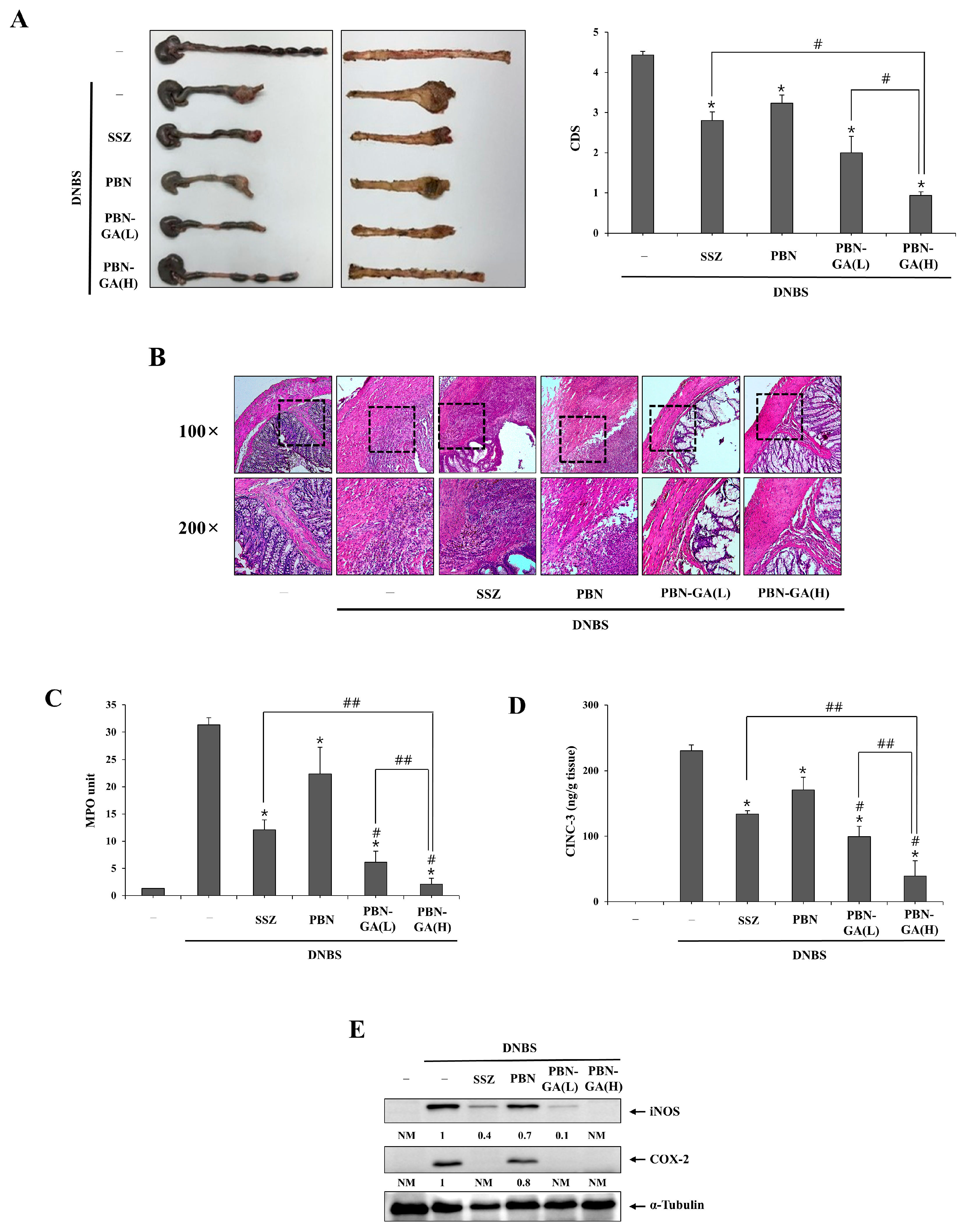

3.3. PBN-GA Enhances the Anticolitis Activity of PBN and Is Therapeutically Superior to SSZ

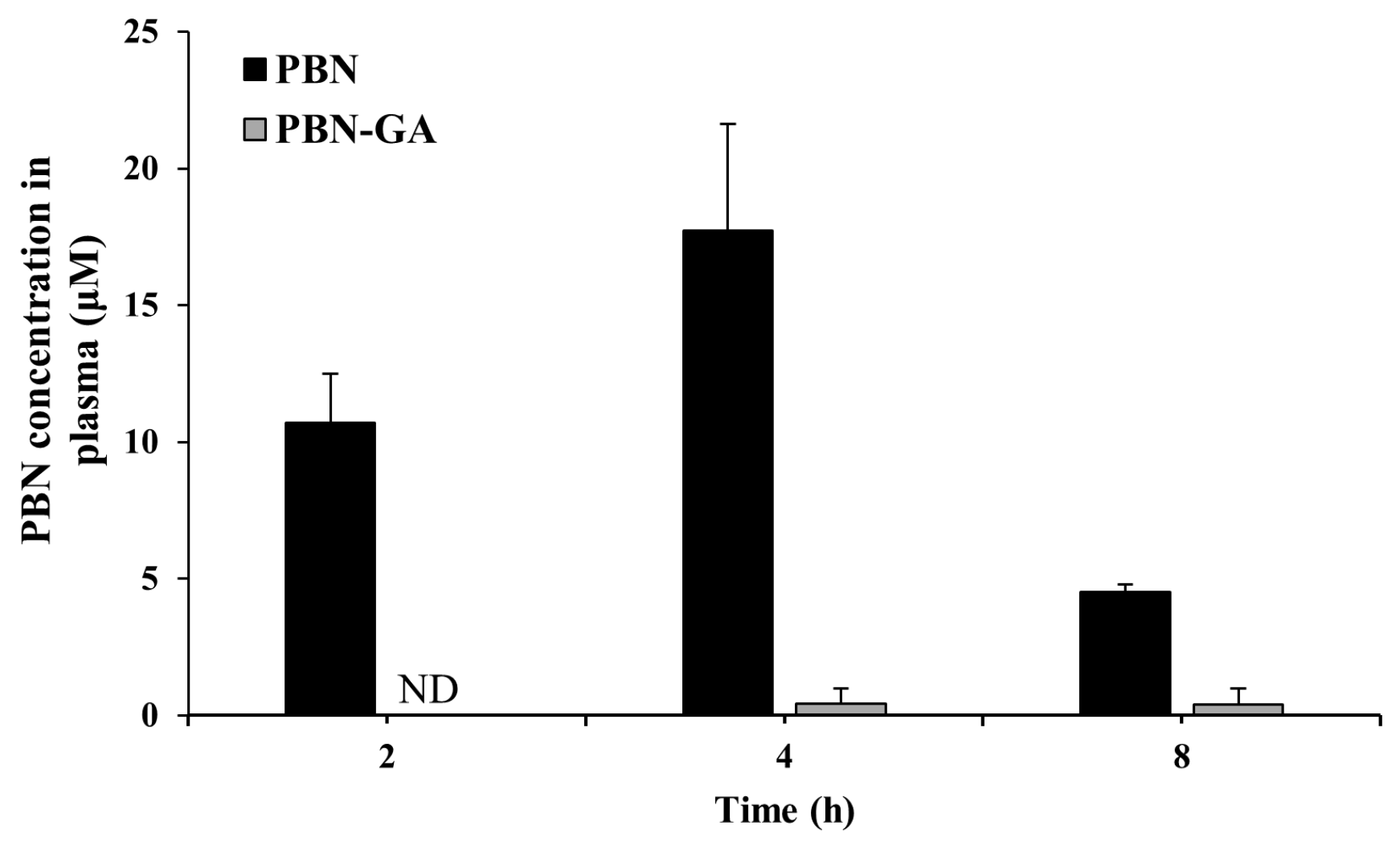

3.4. PBN-GA Reduces the Risk of Systemic Adverse Effects of PBN

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ko, J.K.; Auyeung, K.K. Inflammatory bowel disease: Etiology, pathogenesis and current therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Scholmerich, J. Extraintestinal manifestations and complications in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithadia, A.B.; Jain, S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Pharmacol. Rep. 2011, 63, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.V.; Brain, O.; Travis, S.P. Conventional drug therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbrizi, M.; Magro, F.; Coy, C.S.R. Pharmacological Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Narrative Review of the Past 90 Years. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, D.C.; Le Berre, C. Newer Biologic and Small-Molecule Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Avalle, C.; D’Amico, F.; Gabbiadini, R.; Dal Buono, A.; Pugliese, N.; Zilli, A.; Furfaro, F.; Fiorino, G.; Allocca, M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; et al. JAK inhibitors in crohn’s disease: Ready to go? Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2022, 31, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N.; Koch, S.E.; Tranter, M.; Rubinstein, J. The History and Future of Probenecid. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2011, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusiecka, O.M.; Tournier, M.; Molica, F.; Kwak, B.R. Pannexin1 channels—A potential therapeutic target in inflammation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1020826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainz, N.; Wolf, S.; Tschernig, T.; Meier, C. Probenecid Application Prevents Clinical Symptoms and Inflammation in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Inflammation 2015, 39, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, W.; Locovei, S.; Dahl, G. Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2008, 295, C761–C767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rodríguez, C.; Mujica, P.; Illanes-González, J.; López, A.; Vargas, C.; Sáez, J.C.; González-Jamett, A.; Ardiles, Á.O. Probenecid, an Old Drug with Potential New Uses for Central Nervous System Disorders and Neuroinflammation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekeni, F.B.; Elliott, M.R.; Sandilos, J.K.; Walk, S.F.; Kinchen, J.M.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Armstrong, A.J.; Penuela, S.; Laird, D.W.; Salvesen, G.S.; et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature 2010, 467, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo Yanguas, S.; Willebrords, J.; Johnstone, S.R.; Maes, M.; Decrock, E.; De Bock, M.; Leybaert, L.; Cogliati, B.; Vinken, M. Pannexin1 as mediator of inflammation and cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.P.; Martin, D.E.; Murray, J.; Sancilio, F.; Tripp, R.A. Probenecid Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs). Biomolecules 2025, 15, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, W.R.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Locovei, S.; Qiu, F.; Carlsson, S.K.; Scemes, E.; Keane, R.W.; Dahl, G. The pannexin 1 channel activates the inflammasome in neurons and astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18143–18151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diezmos, E.F.; Markus, I.; Perera, D.S.; Gan, S.; Zhang, L.; Sandow, S.L.; Bertrand, P.P.; Liu, L. Blockade of Pannexin-1 Channels and Purinergic P2X7 Receptors Shows Protective Effects Against Cytokines-Induced Colitis of Human Colonic Mucosa. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulbransen, B.D.; Bashashati, M.; Hirota, S.A.; Gui, X.; Roberts, J.A.; MacDonald, J.A.; Muruve, D.A.; McKay, D.M.; Beck, P.L.; Mawe, G.M.; et al. Activation of neuronal P2X7 receptor-pannexin-1 mediates death of enteric neurons during colitis. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, Y.M. What should be considered on design of a colon-specific prodrug? Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2010, 7, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Shah, T.; Amin, A. Therapeutic opportunities in colon-specific drug-delivery systems. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2007, 24, 147–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, S.; Ju, S.; Kim, S.; Yoo, J.W.; Yoon, I.S.; Min, D.S.; Jung, Y. Preparation and Evaluation of Colon-Targeted Prodrugs of the Microbial Metabolite 3-Indolepropionic Acid as an Anticolitic Agent. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Ju, S.; Kim, W.; Cho, H.; Kim, H.Y.; Heo, G.; Im, E.; Yoo, J.W.; et al. 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Azo-Coupled with a GPR109A Agonist Is a Colon-Targeted Anticolitic Codrug with a Reduced Risk of Skin Toxicity. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kang, C.; Kim, J.; Ju, S.; Yoo, J.W.; Yoon, I.S.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y. A Colon-Targeted Prodrug of Riluzole Improves Therapeutic Effectiveness and Safety upon Drug Repositioning of Riluzole to an Anti-Colitic Drug. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 3784–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, B.; Bhardwaj, T.R.; Singh, R.K. Design, synthesis and studies on novel polymeric prodrugs of erlotinib for colon drug delivery. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem.-Anti-Cancer Agents 2021, 21, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sang, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, A. Polysaccharide-based micro/nanocarriers for oral colon-targeted drug delivery. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, S.; Ju, S.; Lee, H.; Jeong, S.; Yoo, J.W.; Yoon, I.S.; Jung, Y. Colon-Targeted Delivery Facilitates the Therapeutic Switching of Sofalcone, a Gastroprotective Agent, to an Anticolitic Drug via Nrf2 Activation. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4007–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkinson, G. Sulphasalazine: A Review of 40 Years’ Experience. Drugs 1986, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, C.; Yoo, J.W.; Yoon, I.S.; Jung, Y. N-Succinylaspartic-Acid-Conjugated Riluzole Is a Safe and Potent Colon-Targeted Prodrug of Riluzole against DNBS-Induced Rat Colitis. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Yum, S.; Yoo, H.J.; Kang, S.; Yoon, J.H.; Min, D.; Kim, Y.M.; Jung, Y. Colon-targeted cell-permeable NFkappaB inhibitory peptide is orally active against experimental colitis. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, R.M.; Abohashem, R.S.; Ahmed, H.H.; Halim, A.S.A. Combinatorial intervention with dental pulp stem cells and sulfasalazine in a rat model of ulcerative colitis. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 3863–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.-R.; Park, H.-J.; Seo, B.-I.; Roh, S.-S. New approach of medicinal herbs and sulfasalazine mixture on ulcerative colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Neogi, T.; Kang, E.H.; Liu, J.; Desai, R.J.; Zhang, M.; Solomon, D.H. Cardiovascular risks of probenecid versus allopurinol in older patients with gout. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N.; Gilbert, M.; Kumar, M.; McNamara, J.W.; Daly, P.; Koch, S.E.; Conway, G.; Effat, M.; Woo, J.G.; Sadayappan, S. Probenecid improves cardiac function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in vivo and cardiomyocyte calcium sensitivity in vitro. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cheon, J.H. Updates on conventional therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases: 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anti-TNF-α. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.; Kumria, R. Colonic drug delivery: Prodrug approach. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, A.K.; Philip, B. Colon targeted drug delivery systems: A review on primary and novel approaches. Oman Med. J. 2010, 25, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Dalal, M.S.; Contreras, J.E. Pannexin-1 channels as mediators of neuroinflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Cao, W.; Wang, Z.; Xu, B.; Li, G.; Li, M. Leucine and glutamic acid attenuate the dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice by modulating the inflammatory response and energy metabolism processes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 145, 110016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onódi, Z.; Koch, S.; Rubinstein, J.; Ferdinandy, P.; Varga, Z.V. Drug repurposing for cardiovascular diseases: New targets and indications for probenecid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 180, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freis, E.D.; Sappington, R.F. Long-term effect of probenecid on diuretic-induced hyperuricemia. JAMA 1966, 198, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, Y.; Kim, J.; Kang, C.; Jung, Y. Colon-Specific Delivery of Probenecid Enhances Therapeutic Activity of the Uricosuric Agent Against Rat Colitis. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111454

Jeong Y, Kim J, Kang C, Jung Y. Colon-Specific Delivery of Probenecid Enhances Therapeutic Activity of the Uricosuric Agent Against Rat Colitis. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111454

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Yeonhee, Jaejeong Kim, Changyu Kang, and Yunjin Jung. 2025. "Colon-Specific Delivery of Probenecid Enhances Therapeutic Activity of the Uricosuric Agent Against Rat Colitis" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111454

APA StyleJeong, Y., Kim, J., Kang, C., & Jung, Y. (2025). Colon-Specific Delivery of Probenecid Enhances Therapeutic Activity of the Uricosuric Agent Against Rat Colitis. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111454