Abstract

Even though Pt(II)-based drugs represent the standard in cancer therapy, their use is seriously limited by severe side-effects (renal toxicity, allergic reactions, gastrointestinal disorders, hemorrhage and hearing loss), drug resistance and a grim prognosis. This review presents the results of multiple studies showing different nanoparticle-based platforms as delivery agents in order to overcome these drawbacks. The approach of using nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems of Pt drugs and prodrugs is promising due to key advantages like specific targeting and thereby reduced toxicity to healthy cells; increased stability in the bloodstream; multiple mechanisms of action such as stimulating anti-tumor immunity, responding to environmental stimuli (light, pH, etc.), or penetrating deeper into tissues; enhanced efficacy by their combination with other therapies (chemotherapy, gene therapy) to amplify the anti-tumor effect. However, certain challenges need to be overcome before these solutions can be widely applied in clinics. These include issues related to biocompatibility, large-scale production, and regulatory approvals. In conclusion, using nanoparticles to deliver Pt-based drugs represents an advanced and highly promising strategy to make chemotherapy more effective and less toxic. Nonetheless, further studies are required for the better understanding of intracellular mechanisms of action, toxicity and the pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles, and physical–chemical standardization.

1. Introduction

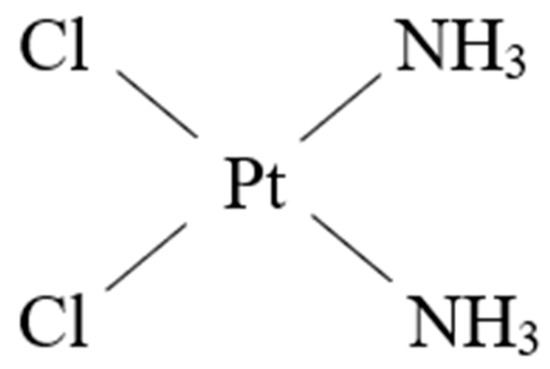

Transition metal complex-based medicine represents a promising approach for different therapies due to their wide range of actions (anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer), as they can interact with various biological targets, such as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or enzymes, and can induce the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1]. As a result, researchers seek to discover new metal-based anticancer drugs like Pd(II)-based ones, with lower side-effects. However, Pt(II)-based drugs continue to represent the standard in cancer therapy [1]. The synthesis of cisplatin, cis-[Pt(II)(NH3)2Cl2] ([PtCl2(NH3)2] or CDDP), a Pt(II) complex, was an important discovery representing proof of Pt(II)-containing compounds’ potential as anticancer drugs and encouraged the study of other transition metal-containing complexes [2,3]. However, their use in different schemes is seriously limited by severe side-effects, drug resistance and a grim prognosis [4]. Consequently, the research subject moved to Pt(IV)-based prodrugs, which can exert their anticancer effects after reduction to their Pt(II) counterparts, having fewer side-effects. Therefore, several Pt(IV) compounds, like ormaplatin or tetraplatin, iproplatin and oxoplatin, are the subject of current research [5,6,7]. To overcome conventional Pt-based drug impediments, the usage of supramolecular chemistry was proposed to produce novel delivery platforms integrating the biological properties of Pt compounds and new supramolecular structures, such as nanoparticle (NP)-based delivery systems [1,8]. Besides NP-based delivery and prodrug methods, ligand modification strategies were employed to increase the selectivity of anticancer agents and reduce their side-effects [1]. NP-based drug delivery platforms seem to deliver Pt(IV) prodrugs more selectively and safely to cancer cells, but clinical outcomes were nevertheless unpredictable because of insufficient in vivo pharmacokinetics studies [9].

In this work, we aimed to present some of the most recent research in the field of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems of Pt anticancer drugs, focusing on their structure, pharmacokinetics, mechanism of action and alternatives of reducing the severe side-effects of conventional cancer therapy.

2. Conventional Pt(II)-Based Cancer Therapy and Its Limitations

Ever since cisplatin (Figure 1) received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for cancer therapy in the 1970s, Pt-based anticancer drugs have become the standard of chemotherapy treatments. However, their wider use is highly limited due to severe side-effects and drug resistance [10].

Figure 1.

The structure of cisplatin.

Cisplatin has been used for the therapy of an array of human tumors like bladder, head and neck, lung, ovarian, and testicular cancers, and against various types of cancers, including carcinomas, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, and sarcomas [11]. It can induce cancer cell death by crosslinking with the purine bases on the DNA, interfering with DNA repair processes, eventually leading to DNA damage [11].

Even though cisplatin has been used for the treatment of numerous human cancers and is effective against various types of cancers, its use is limited by drug resistance and numerous undesirable side-effects such as severe kidney problems, allergic reactions, decreased immunity to infections, gastrointestinal disorders, hemorrhage, and hearing loss especially in younger patients.

The mechanisms of their production and the associated complications and symptoms are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

The side-effects induced by cisplatin therapy.

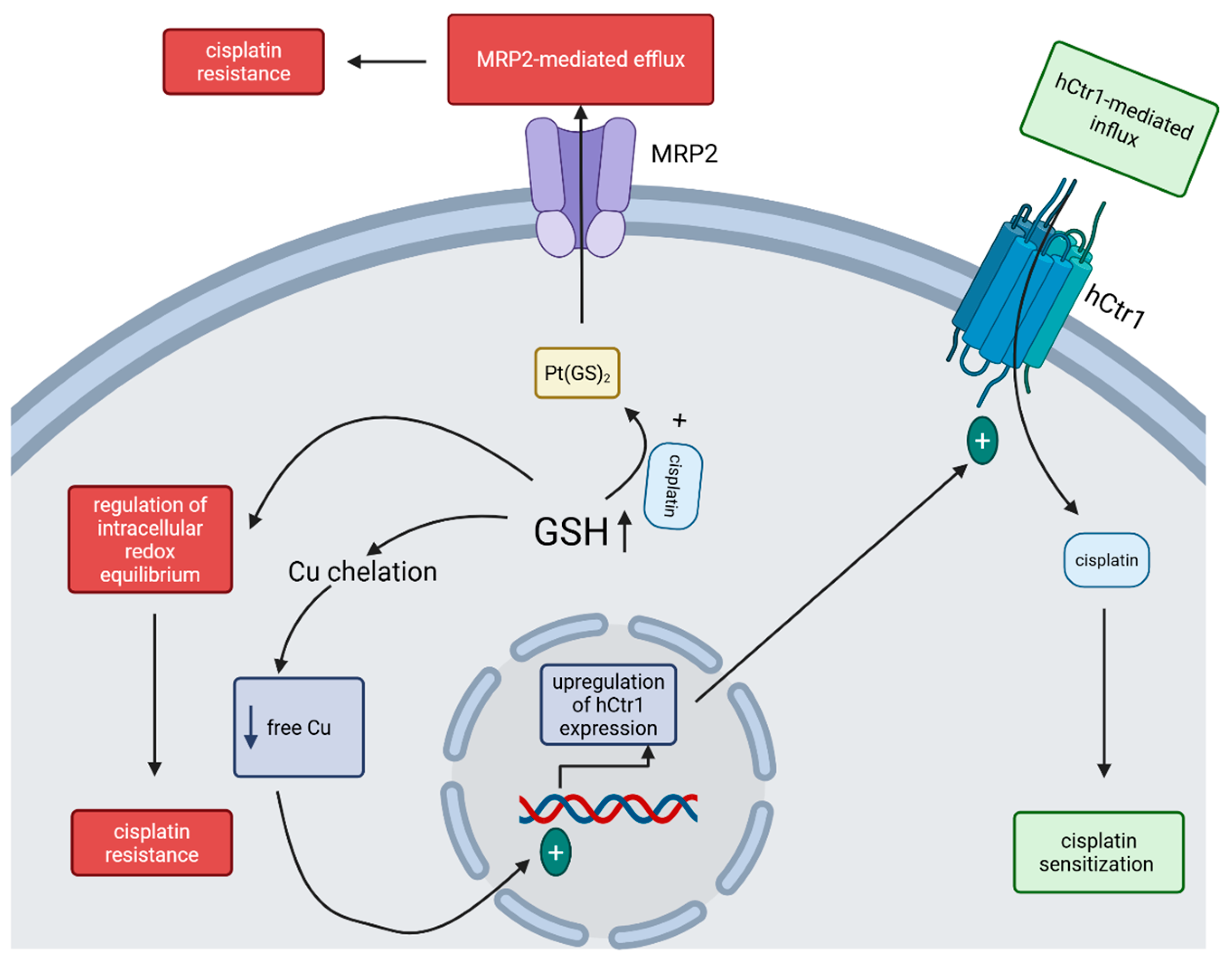

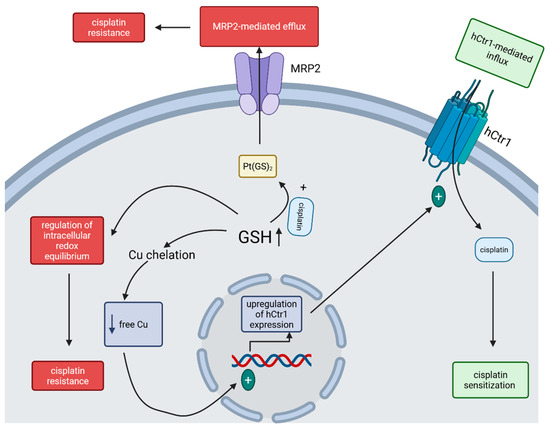

Developing drug resistance is common in cisplatin therapy, and it can occur due to high thiol-containing species (especially glutathione (GSH)) levels within the cancer cell and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent GSH S-conjugate pumps [20]. Several processes are considered in explaining the influence of GSH on cisplatin transport: GSH may function as a cofactor in the ATP-dependent MRP2-mediated efflux of Pt(GS)2—a conjugate formed between cisplatin and elevated intracellular GSH—thereby contributing to cisplatin resistance in cancer cells; GSH acts as a cytoprotective agent—highly elevated in cancer cells due to the enhanced activity of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (the rate-limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis) and therefore being able to regulate the intracellular redox equilibrium, which contributes to cisplatin resistance; high levels of GSH, by chelating Cu, decreasing Cu levels within cells, and can therefore induce the overexpression of the high-affinity Cu transporter (hCtr1) which also functions as a cisplatin transporter—by mediating cisplatin uptake, its sensitivity to this drug is increased (Figure 2) [21,22].

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of GSH-regulated cisplatin sensitivity of tumor cells. The increased GSH level inside the cancer cell can, on one hand, enhance the MRP2-mediated efflux of cisplatin and regulate the intracellular redox equilibrium, leading to cisplatin resistance, and, on the other hand, lower the level of free Cu within the cell, upregulate the expression of hCtr1, increase the hCtr1-mediated cisplatin influx and lead to sensitization to cisplatin. (Created in BioRender. Iova, V. (2025) https://BioRender.com/wys8gdv, accessed on 23 July 2025).

The importance of each of these mechanisms might depend on the specific type of cancer cell and its physiological state. While ATP-dependent MRP2-mediated efflux of cisplatin requires GSH, Pt(GS)2 formation as an important step for cisplatin elimination remains somewhat controversial as different studies show different results [21]. Additionally, cisplatin can induce the upregulation of γ-GCSh and MRP, thus enhancing the cisplatin efflux [21]. Nevertheless, transfection of recombinant DNA coding only for the γ-GCSh subunit leads to an increase in GSH levels in the transfected cells, with a surprising hypersensitivity instead of resistance to cisplatin toxicity, which was proved to be linked with the enhanced uptake of cisplatin in these transfected cells through the upregulation of hCtr1 [21]. Future investigations are needed to clearly demonstrate the role of GSH in regulating the cisplatin sensitivity of cancer cells.

3. Pt(IV) Anticancer Prodrugs

Pt(IV) compounds were synthesized and preclinically (mostly only in vitro) tested to counteract the severe side-effects and drug resistance associated with classical Pt(II) compounds [23]. The octahedral Pt(IV) compounds, that are kinetically inactive, were developed using different synthesis techniques such as conjugation with lipid chains to increase lipophilicity; combination with small peptide segments or NPs to increase drug delivery efficacy; incorporation of bioactive ligands to the axial positions of Pt(IV) compounds for dual-function effects, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors, p53 agonists, alkylating agents, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory molecules—molecules that are released after the reduction reaction of the prodrugs to their corresponding Pt(II) active counterparts [24,25,26,27]. This reduction process occurs within the cancer cell due to the redox disequilibrium at the high metabolic rate, increased mitochondrial dysfunction, highly activated cell signaling pathways and fast peroxisomal activities [26,27].

4. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems of Pt Drugs in Cancer Therapy

There are many research directions regarding the next generation Pt chemotherapy and the NP-based delivery platforms of Pt complexes (such as various Pt-polymer complexes, micelles, dendrimers and liposomes) providing promising preclinical and clinical results [28]. Several properties and mechanisms of action of NPs encapsulating Pt drugs were studied (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nanoparticle properties and functional mechanisms for platinum drug delivery.

There are many biological models used to assess the performance of NPs delivering Pt-based drugs or prodrugs, such as cancer cell lines (for example, MCF-7, HeLa and A549), mouse xenograft models, syngeneic mouse models or patient-derived xenografts [29,30,31]. For the approval of Pt-based nanoformulations in clinical practice, further research and clinical validation are required to confirm the promising results of preclinical studies. Different platforms, such as lipid-based NPs, polymeric NPs, inorganic NPs, and extracellular vesicles were proved to provide increased drug targeting, bioavailability, reduced systemic toxicity in preclinical and clinical studies, the capacity to reverse drug resistance and the potential to be used in combination therapy. However, problems linked to biocompatibility, scalability, and regulatory approval need to be solved for widespread clinical adoption [32].

4.1. Strategies Used for a More Efficient Cancer Treatment

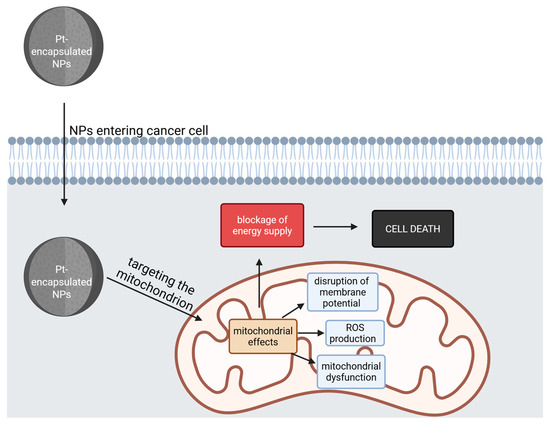

4.1.1. Mitochondria Targeting

It was thought and further demonstrated that anticancer drugs targeting mitochondria could potentially overcome or reverse cisplatin resistance [33]. Mitochondria have a central place in the study of tumoral resistance to cisplatin for two reasons. Firstly, the reprogramming and variability of tumor metabolism contributes to cisplatin resistance in cancer cells by enabling a switch between mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. Secondly, mitochondrial DNA is more prone to being damaged by Pt-based drugs, and this results in affected mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [33].

The latest achievements in mitochondria-targeting are pointing to a self-assembled drug delivery nanoplatform formed by lonidamine (LND)-S-S-Pt-triphenylphosphine (TPP)/β-cyclodextrin-grafted hyaluronic acid (HA-CD) synthesized to destroy cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells, with every component comprising the nanomolecule bearing an important role: HA-CD can find the CD44 receptor on the tumor cell membrane; TPP may target the mitochondria, where the disulfide bond linking LND and the Pt(IV) prodrug is broken by the high levels of GSH, leading to the release of LND that can inhibit glycolysis and damage these organelles; the Pt(IV) molecule is reduced to cisplatin by GSH and further causes mitochondrial damage by targeting the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). By decreasing the intracellular level of GSH, this nanoplatform overcame GSH-mediated chemotherapy resistance [33].

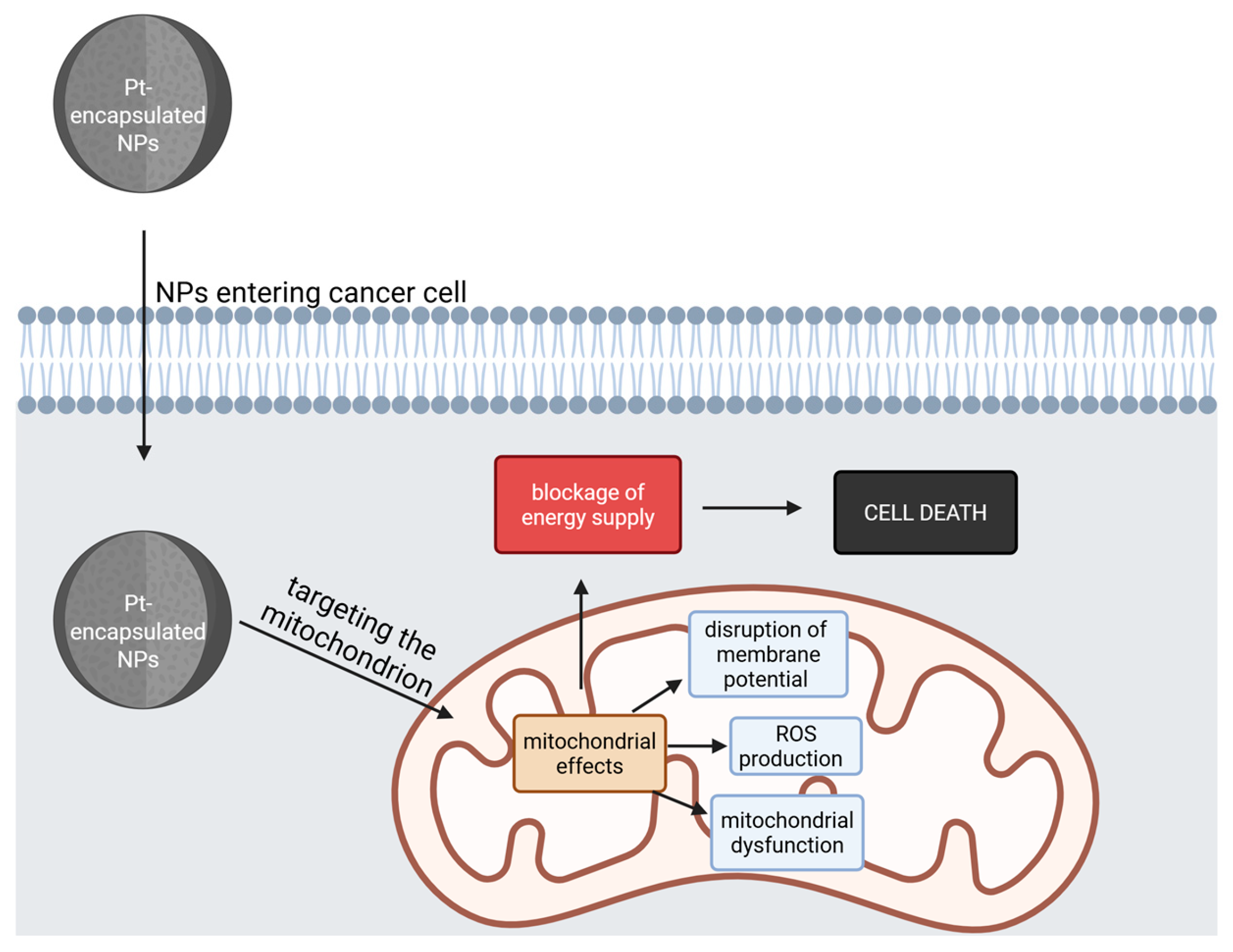

Another recent method for targeting mitochondria is represented by the linkage of oxoplatin with lithocholic acid that self-assemble in water to spherical-shaped NPs. Their mechanisms of action might require the reduction in the Pt(IV) core to Pt(II) and simultaneous release of lithocholic acid, both being important for the anticancer effect. It was showed that the complex with the greatest potency was the one bearing a heptanoate rest linked to the Pt(IV) core at the axial trans position to the lithocholic acid rest [34]. It can affect the cancer cell by various mechanisms: halting the cell cycle in the S and G2 phases, affecting DNA, disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential, increasing ROS production, affecting mitochondrial bioenergetics in PC3 cells associated with human prostate cancer, upregulating pro-apoptotic proteins and reducing anti-apoptotic ones from the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCl-2) family [34,35,36] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Latest Pt nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems and formulation targeting mitochondria.

The general mitochondrial effects of these compounds are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The general effects on mitochondria of Pt-encapsulated NPs. After entering the cancer cell, the NPs target and damage the mitochondria, leading to a blockage of energy supply, causing cell death (Created with BioRender https://biorender.com/0hj2h8q, accessed on 1 august 2025).

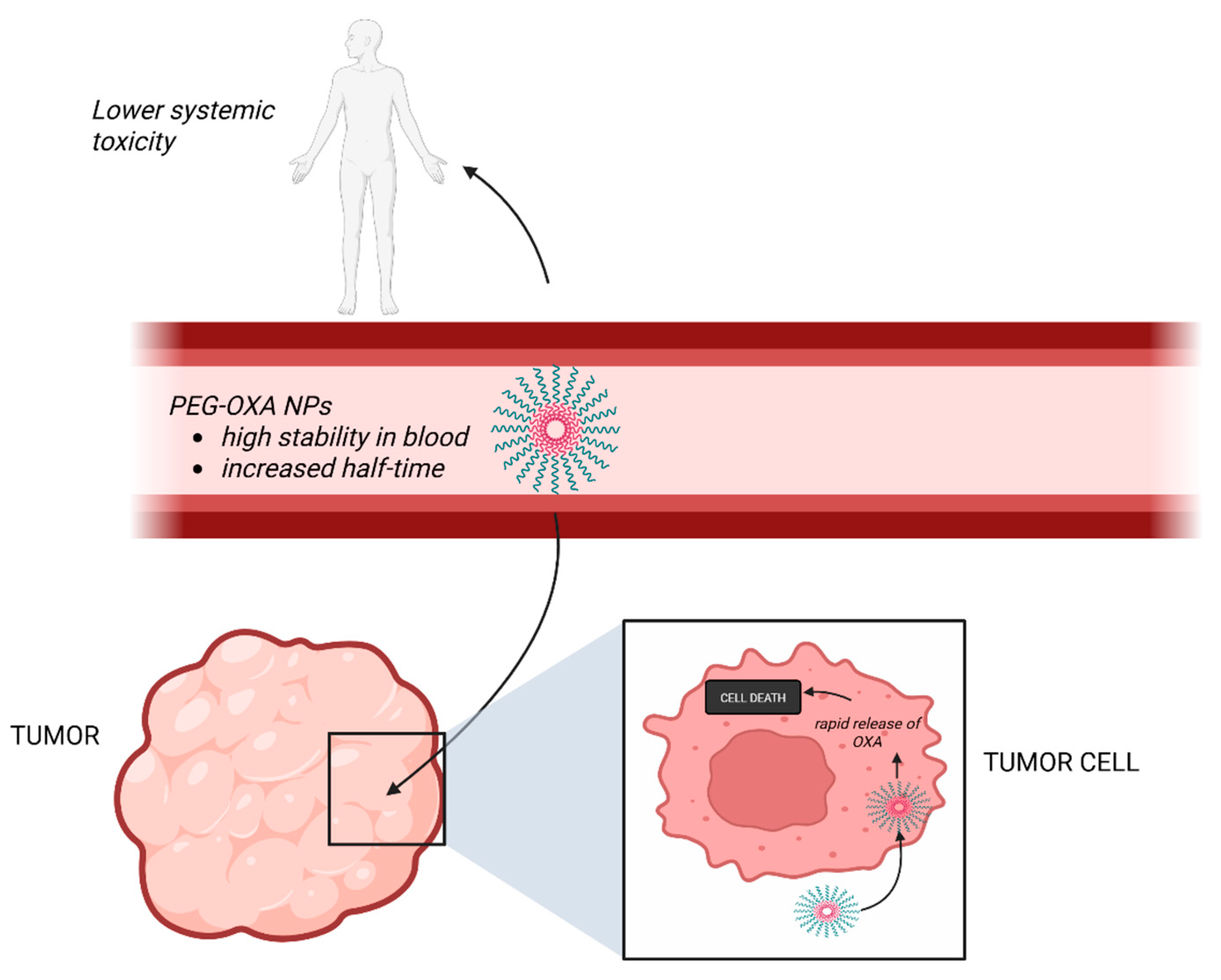

4.1.2. Increased Blood Stability

The study of pharmacokinetics is pivotal for the understanding of drug therapeutic potential. Optimizing absorption, delivery and elimination of Pt-based anticancer drugs is essential to increase antitumor efficacy, decrease side-effects and enhance inhibition of the growing of tumors, and a type of NPs, designated PEG-OXA NPs, appear to exhibit these characteristics [9]. PEG-OXA NPs are formed from a new Pt(IV) complex derived from oxaliplatin (OXA), polyethylene glycol (PEG)-OXA, respectively, that has two hydrophobic lipid rests and the hydrophilic PEG in axial positions and can further self-assemble in micellar NPs in an aqueous environment [9]. These NPs have raised the interest of researchers for they seem to facilitate a rapid release of bioactive OXA in tumor cells and manifest a high stability in blood in vitro and an increased half-life in vivo, thus providing an emerging solution for anticancer drug-targeted delivery [9] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effects of PEG-OXA NPs. These NPs have a high stability in the blood, with an enhanced circulation time, lower systemic toxicity and increased anti-tumor efficacy. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/s4pnyfr, accessed on 1 august 2025).

Besides the novel proposal of PEG-OXA NPs, other recent approaches including nanocrystals, self-assembled PtNPs with protein coronas, nano-hydrogels and mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) are depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Latest Pt nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems and formulation increasing blood stability.

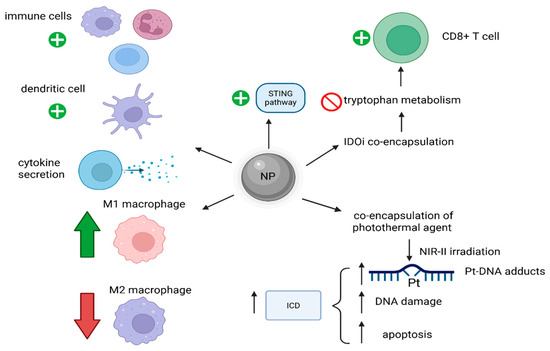

4.1.3. Increased Anti-Tumoral Immunity

One study described a novel NP-based delivery platform for the targeted delivery of Pt(IV) containing a trisulfide bond, which exhibited increased in vivo anticancer properties and reduced liver damage (compared to cisplatin), namely NP(3S)s [41]. Due to high GSH levels within tumor cells, these compounds might release active Pt(II) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) that synergistically act together by impacting DNA (the classical mechanism of Pt(II)); activating the stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway; activating T cells and subsequently increasing antitumor immunity; and activating the OS mechanisms [41].

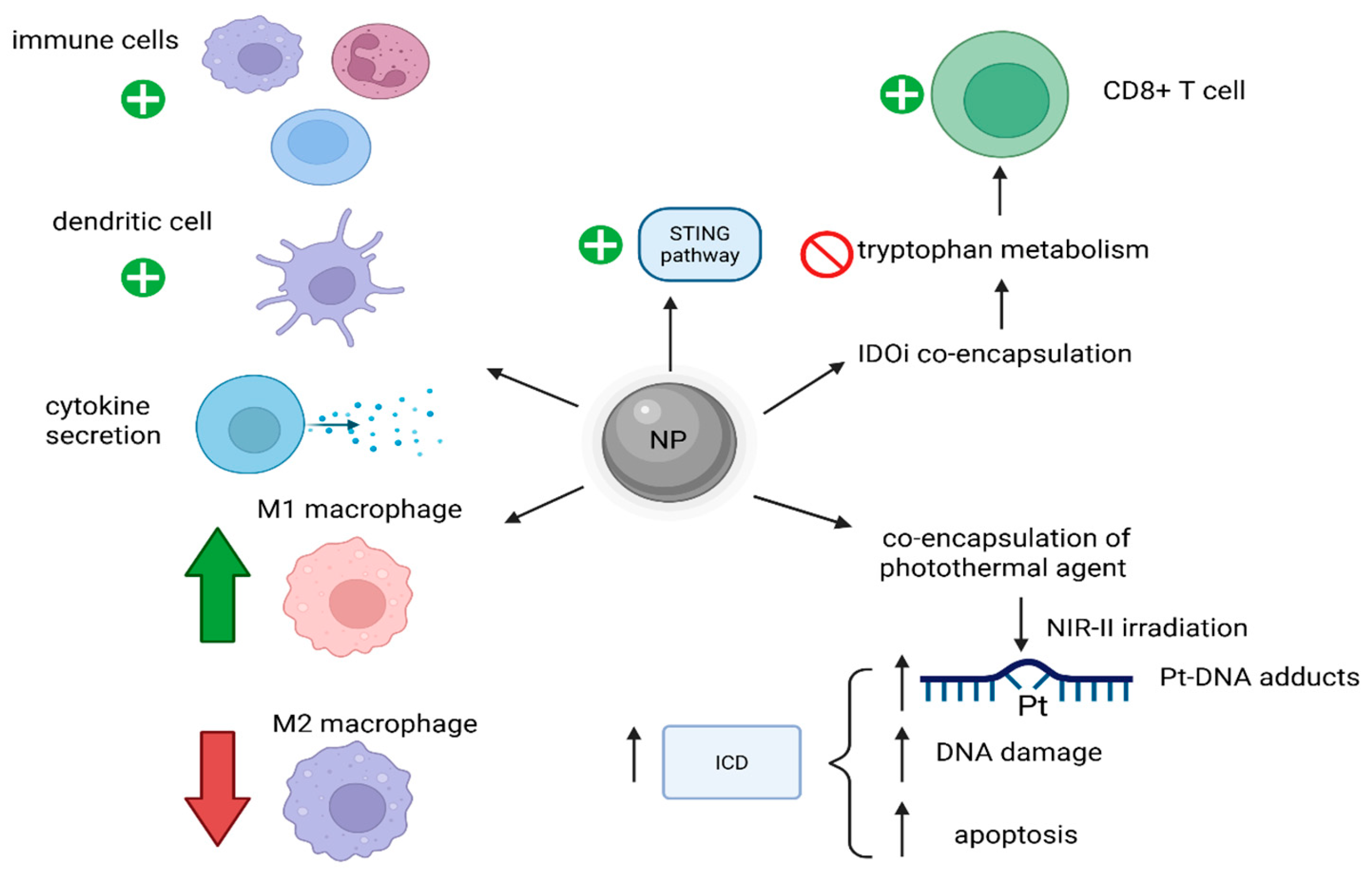

Another efficient combination of Pt-based chemotherapy and immunotherapy was shown for osteosarcoma, a type of cancer where most immune checkpoint blockades were not proved to have good results. For instance, a type of NP designated as NP-Pt-IDOi presented a great antitumor effect [42]. NP-Pt-IDOi was synthesized from a ROS-responsive amphiphilic polymer containing thiol-ketal bonds within its structure by co-encapsulating both a Pt(IV) prodrug and an indoleamine-(2/3)-dioxygenase inhibitor (IDOi) [42]. After entering an environment with high levels of ROS, such as the one in cancer cells, the NP released both encapsulated molecules. The Pt(IV) prodrug was reduced to its Pt(II) counterpart, thus damaging DNA and inducing the STING pathway, with a subsequent increase in antitumoral immunity. The concomitantly released IDOi inhibited the metabolism of tryptophan and, consequently, further activated the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and enhanced the anticancer effects of the nanostructure [42]. Moreover, another way to increase therapy outcome for osteosarcoma by increasing the targeting capacity of the drug and decreasing or reversing the tumor-associated immunosuppression was proved to be achieved by the self-assembly of an OXA-based Pt(IV) prodrug amphiphile, namely Lipo-OXA-ALN, in which alendronate (ALN) acts as a targeting agent for osteosarcoma cells [43]. The effects of the alleged NPs were an enhanced intracellular uptake of OXA, inhibition of cancer cell activity, increased targeting capacity (to spare the healthy bone), increased antitumoral immunity, increased M1/M2 macrophage ratio and modification in the tumoral microenvironment [43].

A further effect of Pt-based drugs, like OXA, is that they can induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) in cancer cells by activating the immune system, and, as a result, strategies to enhance these ICD effects were studied [44]. As a result, it was proved that an NP-encapsulating OXA and a near-infrared-II (NIR-II) photothermal agent IR1061 could achieve this enhancement of ICD in tumors after irradiation with NIR-II, leading to a mild increase in temperature, but with important effects. Increased Pt-DNA binding, higher DNA damage and apoptosis, with subsequent stronger ICD were reported [44]. Such a strategy remarkably increased the therapy results for triple-negative breast cancer 4T1 in comparison with either OXA or NIR-II-based photothermal therapies alone (Figure 5) [44].

Figure 5.

Mechanisms of NP-induced increased anti-tumoral immunity. These NPs activate immune cells, increase cytokine secretion, increase the M1/M2 macrophage ratio and can enhance ICD. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/4ffd2r8, accessed on 1 august 2025).

Current research focuses on Pt-conjugated iron NPs, hyperthermia sensitive Pt NPs and immunogenic bifunctional nanoparticles, as well (Table 5).

Table 5.

Latest Pt nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems and formulations increasing anti-tumoral immunity.

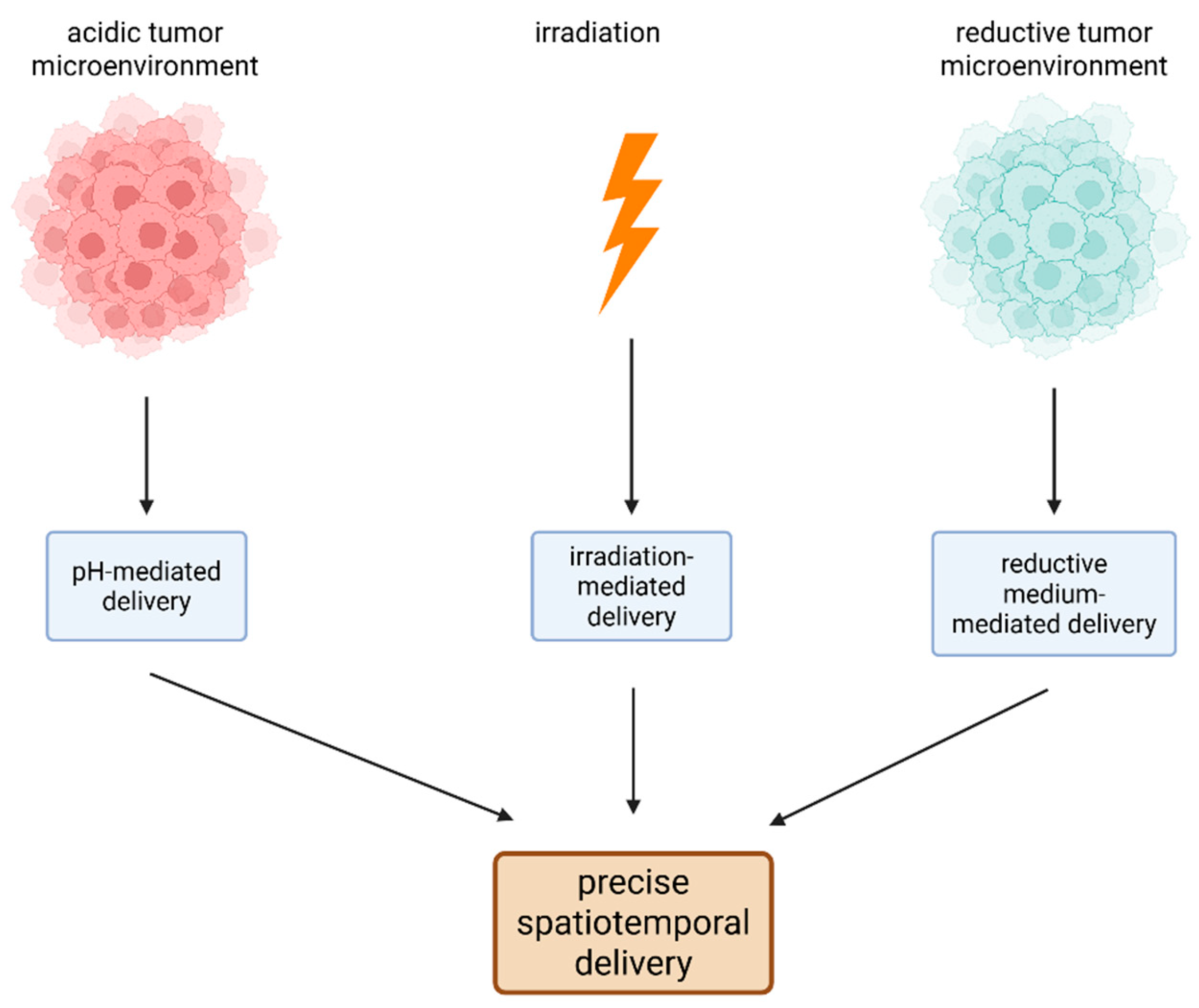

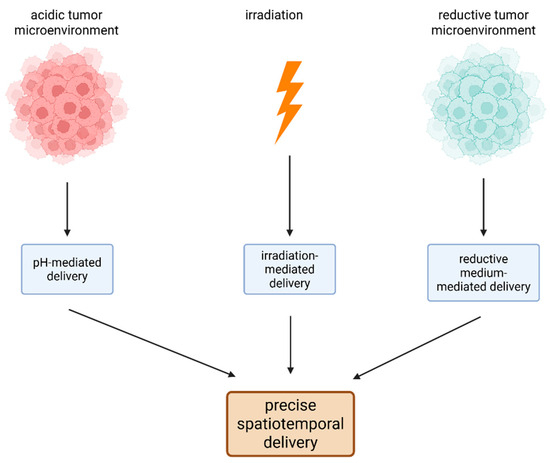

4.1.4. Multistimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems

To overcome the drawbacks of conventional Pt(II) chemotherapy, stimuli-responsive nanoplatform-based delivery systems were considered due to their great potential for exact spatiotemporal drug deliverance [48]. Multistimuli-responsive drug delivery systems are employed to specifically target the site of a drug’s action and release the therapeutic agent by responding to multiple internal and external signals, such as electrical and magnetic fields, acidity, temperature, light irradiation, and redox stimuli [49].

pH-mediated drug delivery methods are on the rise as promising anticancer therapeutic approaches [50]. Liposomes formed from lipid-encapsulated CaCO3 (representing the acidic pH-responsive element of the liposomes) carrying a Pt(IV) prodrug and biotin were proved efficient against thyroid cancer cells, posing high stability and rapid pH-mediated degradation, which, consequently, may direct the pH-responsive delivery of both anticancer molecules [50]. The intracellular effects within the cancer cells of these NPs are increased OS, mitochondrial damage, and DNA damage, ultimately leading to cancer cell death [50].

Another stimuli-responsive approach relies on activation upon irradiation and reduction [48]. Some upconversion NP-based nanoplatforms can incorporate, through hydrophobic interactions, an octahedral Pt(IV) prodrug with an octadecyl aliphatic chain and phenylbutyric acid (i.e., a histone deacetylase inhibitor, with additional anticancer effects) as axial ligands. By further modifications through the binding of 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000 and the peptide arginine-glycine-aspartic, an additional increase in tumor specificity and reduction in systemic toxic effects occur. After upconversion luminescence irradiation and GSH reduction, the NPs release the Pt(II) active counterparts and phenylbutyric acid in the cancer cell cytoplasm, leading to tumor cell death [48].

Synthesis of NPs with both photo- and pH-sensitivity as an encouraging anticancer therapeutic approach was attempted [51]. One such NP is formed from a Pt(IV) prodrug, which can be activated to its Pt(II) active counterpart by ultraviolet A (UVA) irradiation, and demethylcantharidin. Being an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A, demethylcantharidin released from the NP in an acidic medium increases the formation of hyper-phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAkt) to halt the DNA repair mechanisms [51,52]. Additionally, a metallo-nano prodrug was developed by attaching a photosensitizer-conjugated Pt(IV) complex to a polymeric core and chelating it with iron. In an acidic microenvironment, iron released from the NP allows the reduction in Pt(IV) to Pt(II) after light irradiation, leading to chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy [40]. Besides these effects, the NP is supposed to cause ferroptosis and tumor-associated macrophage polarization with additional anticancer consequences [53].

A recent study described a nanozyme-based photocatalytic method for Pt(IV) prodrug activation [54]. The authors reported that an AuNP covered by thiol ligands with 1,4,7-triazacyclononane headgroups encapsulating riboflavin-5′-phosphate (FMN) promoted the photocatalytic reduction in a Pt(IV) prodrug to cisplatin in the presence of a reducing agent [54]. Another current approach employs micellar NPs delivering Pt(IV) prodrugs with photosensitivity which, upon UVA irradiation, show enhanced cytotoxicity towards cancer cells, with reduced side-effects and an increased circulation time [55]. Moreover, two recent studies have brought attention to the development of compounds that can be selectively activated upon irradiation and provide spatial and temporal control over the treatment [56]. In this regard Pt(IV) prodrug NPs that could be activated by deeply penetrating ultrasound radiation are considered as a promising alternative to the common activation of Pt(IV) prodrugs through ultraviolet or blue light irradiation that can reach only the surface, being ineffective against deep or very thick tumors [56] A recent study showed that self-assembled P-Rf/cisPt(IV) NPs transporting a Pt(IV) prodrug and riboflavin, displayed enhanced anti-tumoral properties through an increased activation of the prodrug upon low-intensity ultrasound radiation through superoxide anions, whose formation was increased by riboflavin [57].

Stimuli-responsive techniques might also be employed to overcome resistance to conventional chemotherapy [58]. NPs containing both a Pt(IV) prodrug and ursolic acid known for a higher circulation time, tumor accumulation and antitumor activity but without the side-effects associated with conventional therapy, were proved to reverse cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer in an intracellular reductive and acidic microenvironment through both molecules released [58]. Self-assembled dual-drug polymer micellar NPs and Pt-coordinated dual-responsive nanogels have gained interest as potential anticancer drugs as well (Table 6).

Table 6.

Latest Pt nanoparticle multistimuli-responsive drug delivery systems.

The principles of multistimuli-responsive drug delivery systems are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The principles of multistimuli-responsive drug delivery systems of Pt drugs. Because of the special characteristics of the tumor microenvironment (low pH and an increased level of reductive species) and of the NPs (photosensitivity), precise spatiotemporal delivery of anticancer molecules can occur. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/62axkhb, accessed on 1 august 2025).

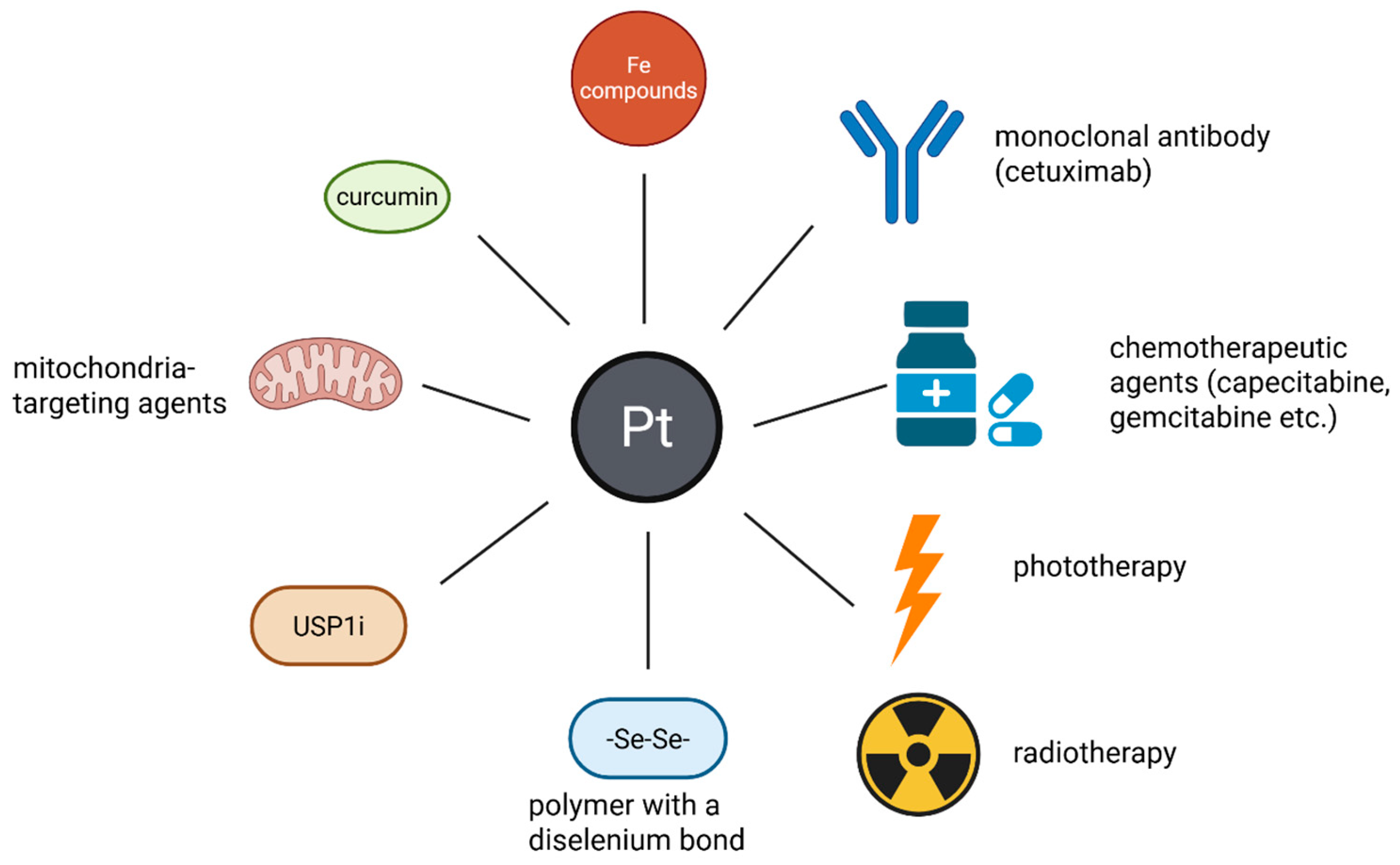

4.1.5. Combination Chemotherapy

Nanotechnology-facilitated combinational delivery of anticancer molecules represents a new promising strategy in tumor therapy [60]. Several compounds co-delivered with Pt-based drugs and prodrugs through nanoplatforms were proposed.

Adding Fe compounds to induce the intracellular cascade reaction and generate sufficient HO• for ferroptosis therapy is of great interest [4,61,62,63,64]. H2O2 depletion-mediated tumor anti-angiogenesis, apoptosis and ferroptosis were found to be achieved by a Pt(IV) prodrug-delivery nanoplatform coated by ferric oxide, which protects the NP in circulation, enhancing delivery to tumor cells, with a selenium core [61]. Several cytotoxic mechanisms on cancer cells were described: ferroptosis caused by HO• accumulation from H2O2 induced by Fe(II) in acidic cancerous medium; inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4); OS augmentation and enhancement of ferroptosis as additional effects of Pt(IV)-reduction to Pt(II) complexes; inhibition of angiogenesis resulting from lower levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A); mitochondrial damage and affected angiogenesis caused by the exposed selenium core [61]. Polypeptide vehicles carrying cisplatin and Fe3O4 NPs were synthesized. They were employed as theranostic agents for combination therapy guided by T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The ferroptosis, caused by the HO• mechanism mentioned above, was implied with the difference that Fe3O4 NPs can also be used for the T2-weighted MRI of the tumor [62]. Another study proposed the synthesis of a GSH-responsive NP containing a disulfide bond-based amphiphilic polyphenol, a dopamine-modified cisplatin prodrug and Fe(III) integrated through coordination reactions between Fe(III) and phenols. Increased OS led to ICD, promoting the maturation of dendritic cells and finally enhancing the antitumor immune response [4].

One promising way for targeted drug delivery might be the conjugation of monoclonal antibodies to different nanosystems. As such, cetuximab was used to decorate a Pt-based drug delivery nanoplatform activated upon NIR irradiation. Cetuximab attachment resulted in a nanosystem capable of specific delivery of drugs to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-hyperexpressing cancer cells in epidermoid carcinoma [65].

In addition, nanoformulation-based drug delivery systems of Pt(IV) prodrugs, like OXA, functionalized with axial ligands represented by other chemotherapeutic agents, like gemcitabine or capecitabine, were proposed. The additional drugs were released upon reduction within cancerous cells with synergistic antitumoral effects and were proved effective in a representative colorectal cancer cell model, with the complexes using gemcitabine being the most active [66].

Multiple studies proposed the association of Pt-based chemotherapy with phototherapy and radiotherapy [20,67,68,69]. The first obvious additional effect besides the therapeutic one is the possibility of simultaneously monitoring the delivery of the Pt-prodrugs by bioimaging [67,68,70]. When synthesis of NPs containing both a Pt(IV) prodrug and a mitochondria-targeting NIR photosensitizer, namely IR780, was developed, it was found that the NIR laser irradiation led to the inhibition of hyperactive energy-generating processes of mitochondria through both photothermal and photodynamic mechanisms, leading to a hindrance of processes requiring energy in the form of ATP, like drug efflux out of the cancer cells or repair of damaged nuclear acids [67,71]. As a result, decrease in pivotal proteins of the nucleotide excision repair pathway activity was induced, thereby enhancing the effects of the Pt-based drugs on the cancer cell’s nucleic acids [67]. Moreover, these NPs allow drug delivery and treatment monitoring through NIR fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging [67]. In another study, Pt(IV)-based polymeric prodrug PVPt with amphiphilic properties was used to encapsulate a theranostic agent, the modified cyanine dye 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-((E)-2-((E)-3-((E)-2-(1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3,3-dimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-2-chlorocyclohex-1-en-1-ly)vinyl)-3,3-dimethyl-3H-indol-1-ium bromide (HOCyOH or Cy), respectively, through hydrophobic interactions, resulting in NPs formed by self-assembly [68]. These NPs could undergo disassembly and activation under acidic, reductive conditions and NIR laser irradiation, being accompanied by photothermal conversion and increased OS [68]. Regarding the association with radiotherapy, researchers are concentrating on new, safe, and redox-responsive NPs with a higher disulfide density and a better ability to load Pt(IV) prodrugs. These NPs would be useful in reversing cisplatin resistance and improving anticancer outcome by directing more cytotoxic compounds towards tumor cells, scavenging GSH, and causing mitochondrial damage, which would increase Pt-DNA cross-linking and make these cancer cells more sensitive to X-ray radiation. As a result, they are considered promising candidates for anticancer chemoradiotherapy, particularly for cervical cancers [20].

Breaking the redox balance is a promising way to maximize the efficacy of conventional Pt-based cancer therapy because the anticancer activity and drug resistance of chemotherapy are related to the redox state of tumor cells [72]. Therefore, NPs formed from polymers containing a diselenium bond in the main chain surrounding a Pt(IV) prodrug were synthesized. They depleted GSH while increasing the level of OS at the same time, thereby disrupting intracellular redox balance and increasing the antitumoral effect of conventional cisplatin therapy [72].

Additionally, the association of Pt(IV) prodrugs and a ubiquitin-specific protease 1 inhibitor (USP1i) within NPs was found to have an enhanced antitumoral effect in comparison with conventional therapy. USP1i seems to affect the DNA damage repair processes by targeting USP1 to increase the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin against cancer cells [31].

It is widely known that doxorubicin, along with other agents, causes hypoxia-induced multi-drug resistance, resulting in poor therapy results [73]. This process may be reversed and stopped by NPs formed as a co-self-assembly of a PEG-Pt(IV) prodrug and doxorubicin which, under light irradiation, can lead to the generation of oxygen to reverse tumor hypoxia and release active Pt(II) and doxorubicin. Increased OS and enhanced cytotoxicity effects compared to both therapies alone were reported [73].

Another approach combines in NPs an OXA-derived Pt(IV) prodrug and a peptide that targets mitochondria aiming to impact the molecular processes that need energy in the form of ATP [71]. These NPs are supposed to become activated by the acidic tumor microenvironment and increased concentration of GSH within cancer cells, leading to the accumulation of high intracellular levels of Pt-drugs and increased anti-tumoral effects, respectively [71].

Molecules to assess the therapeutic efficacy of the treatment were added besides anticancer drugs and drug tracers [74]. Such NPs were developed from a Pt(IV) compound, a NIR-II fluorophore tracer and a peptide that may be split by caspase-3 and serve as an apoptosis indicator. The combination is considered a promising strategy to determine both the drug pharmacokinetics and its therapeutic success [74].

One strategy potentially effective against cisplatin-resistant tumors might be the synthesis of NPs delivering not only the Pt drug, but also curcumin [75]. This co-delivery platform enhances stability, as well as solubility of curcumin and, additionally, release of the Pt drug and the antioxidant occur in reductive environments, such as those from tumors, with consequent synergistic effects [75] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Latest achievements in the production of NPs for combination chemotherapy.

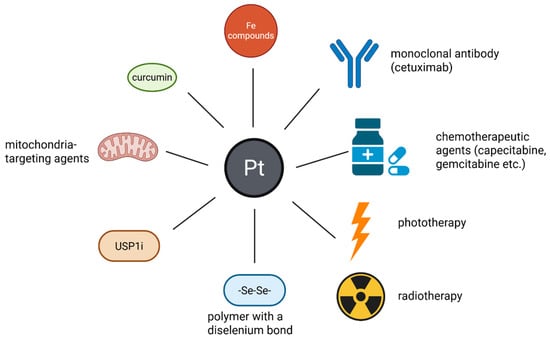

The possibilities of combination therapy using Pt encapsulated by NPs as delivery systems are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The association of Pt drugs/prodrugs with other compounds or techniques in NP-based combination therapy. These Pt compounds can be associated with other elements (Fe compounds or selenium) monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab), other anti-tumor therapies (chemotherapeutic agents—capecitabine, gemcitabine-phototherapy and radiotherapy) mitochondria targeting agents, USP1i and antioxidants (curcumin). These combinations result in an improved anticancer effect, lower systemic toxicity and the possibility to reverse the resistance of tumors to drugs. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/xyg5ul1, accessed on 1 august 2025).

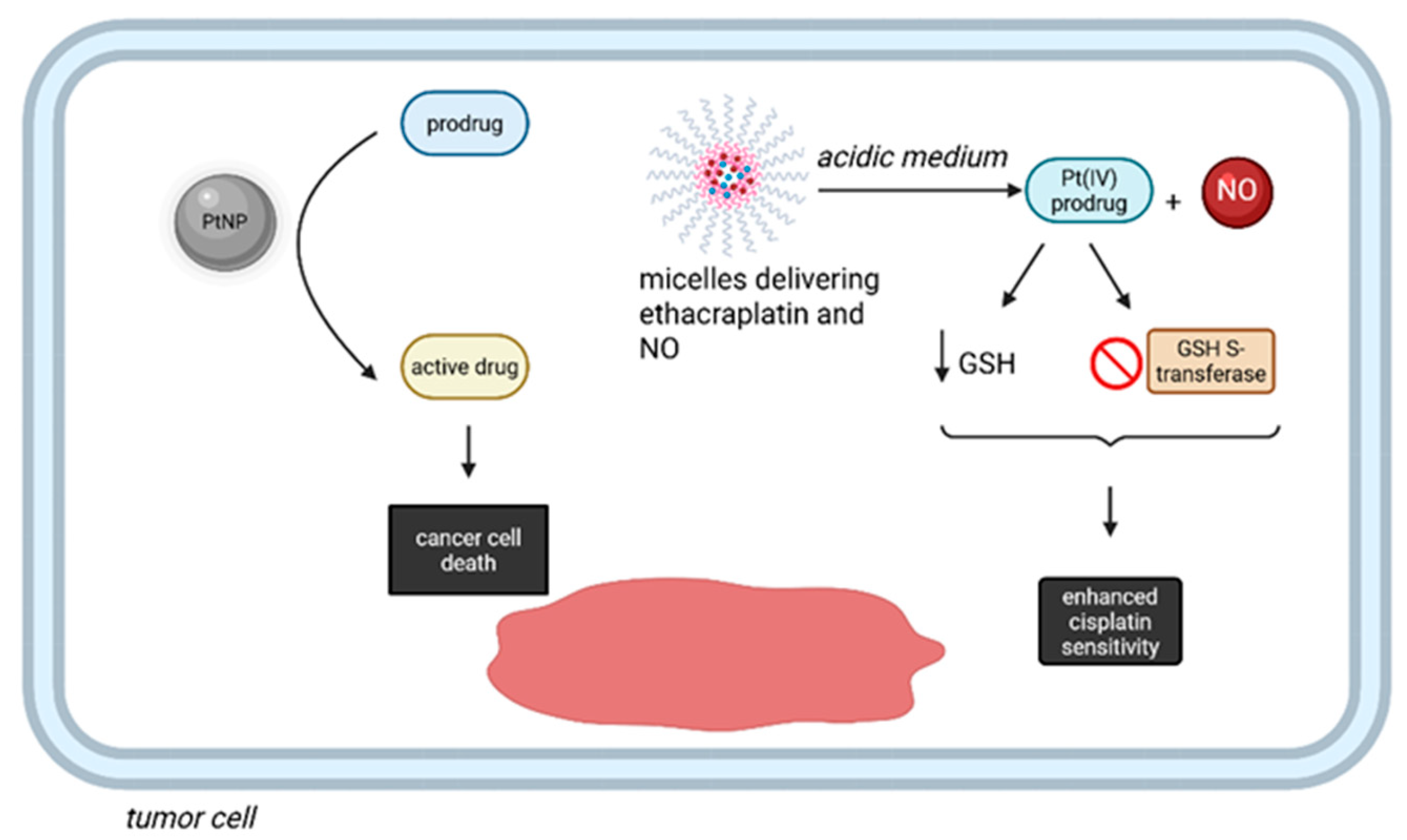

4.1.6. Bioorthogonal Reactions Catalyzed by PtNPs

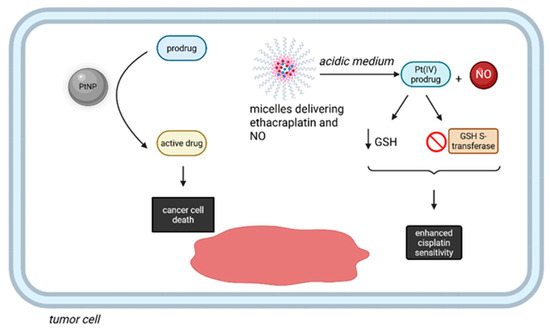

Pt complexes, in addition to their classical role as cytotoxics, were recently proved to perform bioorthogonal reactions in living organisms [76,77]. Even though some methods based on this approach do not directly employ Pt-based prodrugs, PtNPs serve as catalytic centers for a variety of reactions [76]. For instance, the synthesis of catalytic nanoreactors, represented by PEGylated Pt NPs with special properties, such as a dendritic structure and surface shielding by Pt-S-bonded PEG allow the compound to act within the complex intracellular microenvironment of cancer cells, thus enhancing the in situ biorthogonal activation of anticancer prodrugs [76]. Additionally, a combination between biorthogonal chemistry and an inhalation technique was employed to reverse cisplatin resistance in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). The effect was achieved by co-delivery of ethacraplatin (i.e., a Pt(IV) prodrug) and nitric oxide (NO) by micelles, specifically targeting cancer cells after inhalation [77]. After arriving in the acidic tumor microenvironment, the Pt(IV) prodrug is released, inhibits GSH S-transferase and reduces the concentration of GSH, leading to increased sensitivity to cisplatin, with additional advantages associated with the release of NO (Figure 8) [77].

Figure 8.

Bioortoghonal reactions performed by Pt compounds in cancer therapy. PtNPs can act within the complex intracellular microenvironment of cancer cells, with in situ activation of anticancer prodrugs into active molecules. Additionally, micelles delivering ethacraplatin and NO can reduce the intracellular GSH and block GSH S-transferase, thus enhancing the sensitivity towards cisplatin. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/52dh5hc, accessed on 1 august 2025).

A previous study reported the formation of self-assembled coordinative NP BDCNs, which deliver both a Pt(IV) prodrug and a NO prodrug and that accumulate in the tumor. After reduction in the Pt(IV) prodrug to the active Pt(II), activation of NO prodrug occurs by a depropargylation reaction, leading to the release of NO, with synergistic effects [78]. The results of this study show an enhanced the efficiency of bioorthogonal reactions by overcoming the problems posed by the separate administration of the Pt(IV) compound and NO prodrug, such as pharmacokinetic issues [78] (Table 8).

Table 8.

Current progress in bioorthogonal reactions catalyzed by PtNPs.

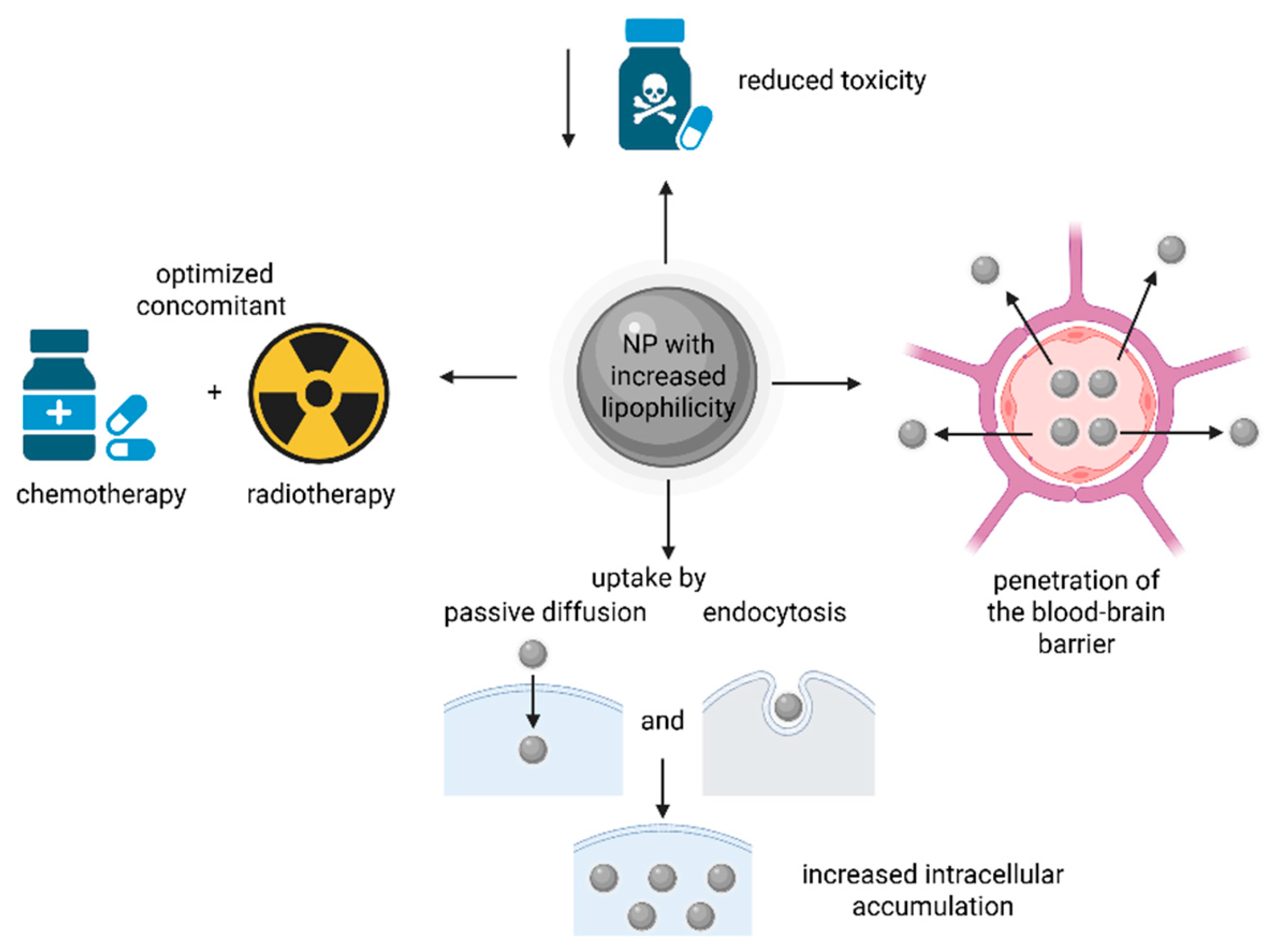

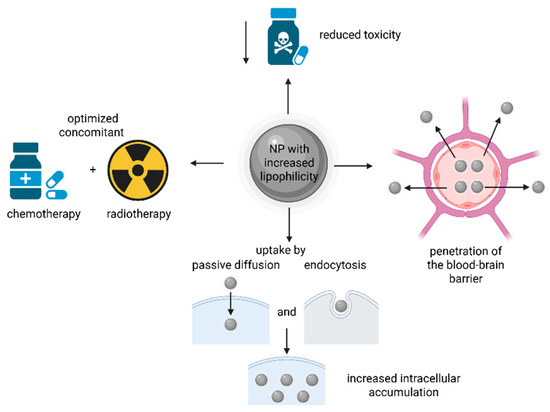

4.1.7. Increased Lipophilicity

Novel nanosystems with enhanced hydrophobicity and passive diffusion capacity, increasing cancer cell accumulation, while combating the drawbacks of conventional therapy and improving the simultaneous chemo-/radiotherapy are emerging. In their development the following objectives are pursued: the deliverance of Pt-based drugs and prodrugs, the pass through the blood–brain barrier, and specifically, the capacity to target malignant cells [79].

It was proved that Pt(IV) prodrugs with increased tumor selectivity formed using biotin and naproxen or stearate in axial position had enhanced anticancer effects. These improved anticancer properties were due to lipophilicity rather than the expression of biotin receptors [80].

Analyzing the importance of lipophilicity of Pt(IV)-based compounds, in an in vitro study, it was suggested that for the most hydrophobic compound tested (namely, diamminedichloridodioctanoatoplatinum(IV)) the formation of nanoaggregates resulted in higher cellular uptake by both passive diffusion and endocytosis than by passive diffusion alone [81]. However, since this compound is active at nanomolar concentrations at which the aggregation in culture media is almost inexistent, this phenomenon should not significantly impact its antiproliferative activity [81]. Another study studied a type of polymeric NP, namely [Pt(DACH)(OAc)(OPal)(ox)] incorporated PLGA NPs, delivering a lypophilic Pt(IV) complex, that showed increased anticancer properties even against cisplatin-resistant cells and reduced systemic toxicity [82] (Table 9).

Table 9.

Latest advancements in the production of NPs delivering lipophilic Pt-based compounds.

The advantages of nanoformulations with increased lipophilicity are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The advantages of NPs with increased lipophilicity in delivering Pt drugs/prodrugs. The increased lipophilicity can help in the penetration of the blood–brain barrier, and the obtained NPs can reduce the systemic toxicity associated with chemotherapy, optimize the chemo-/radiotherapy and increase cancer cell uptake by both passive diffusion and endocytosis. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/efub7kc, accessed on 1 august 2025).

4.1.8. Targeting Both Malignant and Non-Malignant Cells

One more promising efficient cancer therapy in comparison with the conventional approaches is to target both tumoral and non-tumoral cells at the same time. For this purpose, NP-based codelivery of a Pt(IV) prodrug and Sotuletininb (BLZ-945) showed, after irradiation with light having a 660 nm wavelength, a contraction to small Pt(IV) prodrug-containing NPs and drug deliverance deep inside the tumor, while releasing BLZ-945 around the tumor-associated blood vessels, targeting and damaging tumor-associated macrophages [83].

Even though novel approaches were created for cancer therapy by developing various nanoformulation-based drug delivery systems, most of the studies are limited only to in vivo and in vitro research and the number of approved nanodrugs did not significantly increase throughout the years [84,85]. There are also some drawbacks of the usage of NP-based treatments, such as associated-immunotoxicity, long term toxicity, neural side-effects and costly synthesis [84,86] (Table 10).

Table 10.

Current directions in targeting both malignant and non-malignant cells.

4.2. Materials Used in Producing NPs for a More Efficient Cancer Treatment

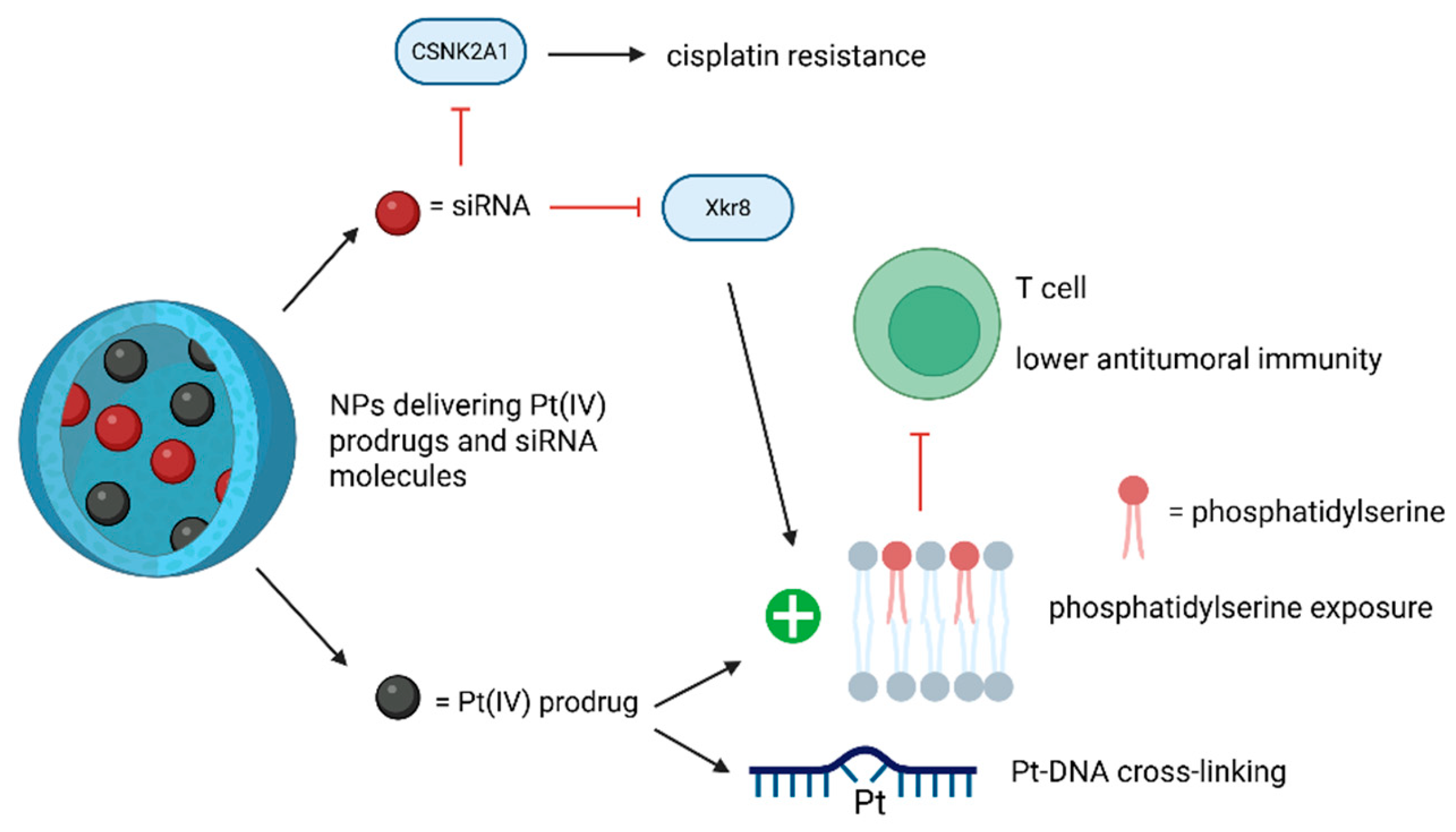

4.2.1. siRNA Technology

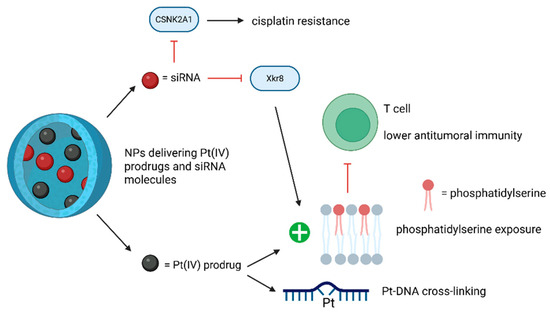

The siRNA technology also appears to play a crucial role in regulating Pt-drug sensitivity.

For instance, epigallocatechin gallate-based NPs carrying both Pt(IV) prodrugs and anti-casein kinase 2 alpha 1 (CSNK2A1) siRNA exerted many beneficial effects by extending the circulation time for Pt-based drugs, increasing the accumulation of the drug within the cancerous cells, decreasing the Pt-drug’s renal side-effects and targeting CSNK2A1, by all of these increasing the tumor’s sensitivity to cisplatin [13].

Another study underlined the potential of utilizing the nuclear-targeting lipid Pt(IV) prodrug with amphiphilic and nuclear-targeting properties to increase Pt-DNA cross-linking formation and using siXkr8 (i.e., small interfering RNA targeting XK-related protein 8) to decrease immunosuppression. This RNA would downregulate the exposed phosphatidylserine (i.e., a phospholipid expressed on cancer cell membrane after Pt-based therapy that binds to corresponding receptors on immune cells, leading to lower antitumoral immunity), leading to improved chemoimmunotherapy. The new compound can thereby amplify the anticancer effects of conventional Pt-based drugs and suppress cancer recurrence [87]. Previous studies showed that self-assembled lipid NP LNP co-delivering XPF-targeted siRNA together with a cisplatin prodrug, can enhance cisplatin-associated cytotoxicity by silencing this nucleotide excision repair (NER)-related gene [88]. Additionally, self-assembled PLGA-PEG/G0-C14 NPs, co-delivering REV1/REV3L-specific siRNA and a cisplatin prodrug, can reverse cisplatin resistance by suppressing the genes involved in the error-prone translesion DNA synthesis [89] (Table 11).

Table 11.

Latest achievements in the production of NPs co-delivering Pt-based compounds and siRNAs.

The roles of siRNA technology in the NP-based drug delivery systems of Pt compounds are depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

The effects of Pt drugs-siRNA NP-based codelivery systems. The use of siRNAs can reverse cisplatin resistance and reduce treatment-associated immunosuppression. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/x1edlli, accessed on 1 August 2025).

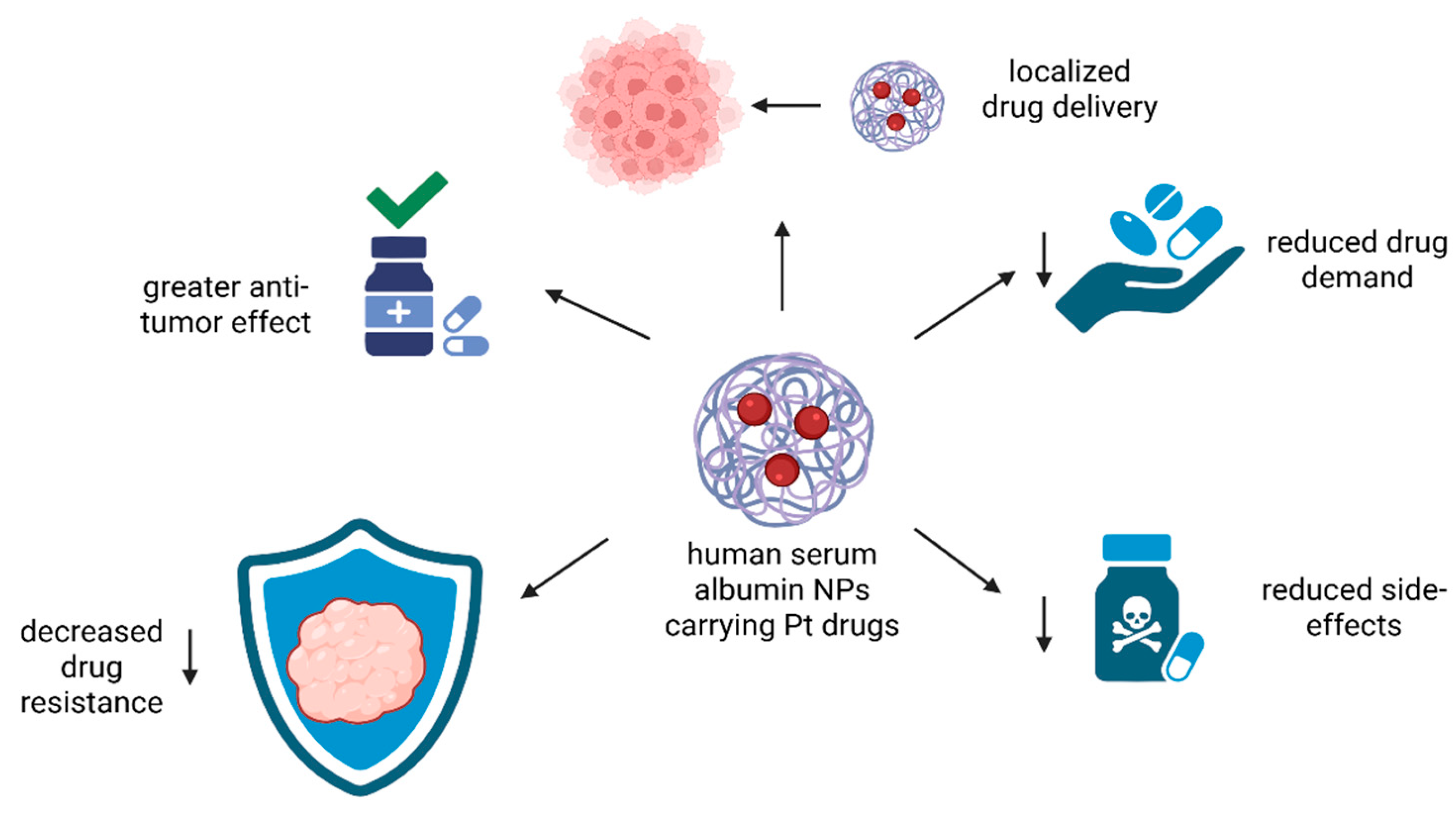

4.2.2. Human Serum Albumin-Based NPs

In addition to the results stated above, precise drug delivery with reduced drug demand and lower side-effects could be achieved using human serum albumin (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The advantages of Pt complexes delivered by human serum albumin NPs. These NPs can help in localized drug delivery, reduce drug demand, lower the intensity of side-effects, reverse resistance to cisplatin and improve the overall anti-tumor effect. (Created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/yolk07y, accessed on 1 august 2025).

Human serum albumin was chosen because studies proved that utilizing this protein is effective for active tumor targeting [90]. The reduction-responsive human serum albumin NPs conjugated with OXA demonstrated improved cytotoxicity and lower rates of resistance compared to the free drug utilization in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer [90]. The same outcomes were reported for AbPlatin(IV) NPs, using human serum albumin as carrier for a lipophilic Pt(IV) prodrug, whose mechanisms of action were analyzed through multi-omics analysis. Modifications of the malignant cell membrane by alterations of glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids and modifications of purine metabolism were discovered [91]. Another study developed human serum albumin–Pt compound complex NPs, HSA-His242-Pt-Dp44mT NPs, which tend to specifically accumulate within cancer cells through the binding of human serum albumin to the secreted protein acidic and are rich in cysteine (SPARC) protein, highly expressed by cancer cells [92]. As a result of this specific binding, enhanced toxicity towards cancer cells and lower side-effects occur [92] (Table 12).

Table 12.

Latest insights in developing human serum albumin-based NPs.

5. Conclusions

NP-based drug delivery systems represent a promising approach in overcoming the disadvantages of conventional Pt-based cancer therapy, namely chemoresistance and severe side-effects, that make the drug’s long-term administration difficult. Passive and active targeting cancer cells through specific drug delivery systems could lead to lowered drug demand and toxicity.

They use different strategies to achieve an improved anticancer effect, such as mitochondria targeting, increased stability in the circulation, increased anti-tumoral immunity, multistimuli-responsivity, combination chemotherapy, catalyzed bioorthogonal reactions, increased lipophilicity and the capacity to target both malignant and non-malignant cells. In addition, other materials or techniques used in combination with these NPs can improve their efficacy, such as the use of siRNAs, laser irradiation, deeply penetrating ultrasound radiation, and human serum albumin-based NPs. Due to their numerous mechanisms of action, NP-based drug delivery systems could enlarge therapeutic utilization for multiple cancers. Nevertheless, there are some challenges regarding the use of different types of NPs in the clinic, such as problems linked to biocompatibility, scalability, and regulatory approval.

Several future directions emerge for this type of nanomedicine. Further studies are still needed to better understand the molecular mechanisms of NPs inside different malignant cells in different patients. Additionally, for wide clinical administration, more studies are required to better analyze toxicity and pharmacokinetics, along with physical–chemical standardization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.I., G.M.I., S.V., A.T.T., I.S. and M.S.T.; methodology, V.I. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.I., G.M.I., S.V., A.T.T., I.S. and M.S.T.; writing—review and editing, V.I., G.M.I., S.V., A.T.T., I.S. and M.S.T.; supervision, M.S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Oradea, Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| OS | oxidative stress |

| Pt | platinum |

| NP | nanoparticle |

| GSH | glutathione |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| MRP2 | multidrug resistance protein 2 |

| Cu | copper |

| LND | lonidamine |

| TPP | triphenylphosphine |

| HA-CD | β-cyclodextrin-grafted hyaluronic acid |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| OXA | oxaliplatin |

| STING | stimulator of interferon genes |

| IDOi | indoleamine-(2/3)-dioxygenase inhibitor |

| ALN | alendronate |

| ICD | immunogenic cell death |

| NIR-II | near-infrared-II |

| UVA | ultraviolet A |

| pAkt | phosphorylated protein kinase B |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| CSNK2A1 | casein kinase 2 alpha 1 |

| siXkr8 | small interfering RNA targeting XK-related protein 8 |

| Au | gold |

| FMN | riboflavin-5′-phosphate |

| Fe | iron |

| OH• | hydroxyl radical |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| VEGF-A | vascular endothelial growth factor-A |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| Cy | 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-((E)-2-((E)-3-((E)-2-(1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3,3-dimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-2-chlorocyclohex-1-en-1-ly)vinyl)-3,3-dimethyl-3H-indol-1-ium bromide |

| USP1i | ubiquitin-specific protease 1 inhibitor |

| S | sulfur |

| NSCLC | nonsmall cell lung carcinoma |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| BLZ-945 | Sotuletininb |

References

- AlAli, A.; Alkanad, M.; Alkanad, K.; Venkatappa, A.; Sirawase, N.; Warad, I.; Khanum, S.A. A comprehensive review on anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anticancer and antifungal properties of several bivalent transition metal complexes. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 160, 108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.M.; Büsselberg, D. Cisplatin as an Anti-Tumor Drug: Cellular Mechanisms of Activity, Drug Resistance and Induced Side Effects. Cancers 2011, 3, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, T.G. Nucleic Acid-Metal Ion Interactions, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 1, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zong, Q.; Lin, T.; Ullah, I.; Jiang, M.; Chen, S.; Tang, W.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Du, J. Self-assembled metal-phenolic network nanoparticles for delivery of a cisplatin prodrug for synergistic chemo-immunotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 3649–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Roh, J.K.; Wolpert-DeFilippes, M.K.; Goldin, A.; Venditti, J.M.; Woolley, P.V. Therapeutic and Pharmacological Studies of Tetrachloro(d,l-trans)1,2-diaminocyclohexane Platinum (IV) (Tetraplatin), a New Platinum Analogue. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pendyala, L.; Cowens, J.W.; Chheda, G.B.; Dutta, S.P.; Creaven, P.J. Identification of cis-dichloro-bis-isopropylamine platinum(II) as a major metabolite of iproplatin in humans. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3533–3536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blatter, E.E.; Vollano, J.F.; Krishnan, B.S.; Dabrowiak, J.C. Interaction of the antitumor agents cis, cis, trans-Pt (IV)(NH3) 2Cl2 (OH)2 and cis, cis, trans-Pt (IV)[(CH3) 2CHNH2] 2Cl2 (OH)2 and their reduction products with PM2 DNA. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 4817–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogadi, W.; Zheng, Y.R. Supramolecular platinum complexes for cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 73, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, D.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Rong, R. Novel Pt(IV) prodrug self-assembled nanoparticles with enhanced blood circulation stability and improved antitumor capacity of oxaliplatin for cancer therapy. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2171158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutphen, S.v.; Reedijk, J. Targeting platinum anti-tumour drugs: Overview of strategies employed to reduce systemic toxicity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Feng, C.; Zhang, W.; Qi, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Tu, C.; Zhou, W. Mitigation of Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity and Augmentation of Anticancer Potency via Tea Polyphenol Nanoparticles’ Codelivery of siRNA from CRISPR/Cas9 Screened Targets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 59721–59737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.P.; Tadagavadi, R.K.; Ramesh, G.; Reeves, W.B. Mechanisms of Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins 2010, 2, 2490–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrilia, N.; Syrigou, E.; Kaklamanos, I.; Manolopoulos, L.; Saif, M.W. Hypersensitivity reactions associated with platinum antineoplastic agents: A systematic review. Met. Based Drugs 2010, 2010, 207084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Sbeih, H.; Mallepally, N.; Goldstein, R.; Chen, E.; Tang, T.; Dike, U.K.; Al-Asadi, M.; Westin, S.; Halperin, D.; Wang, Y. Gastrointestinal toxic effects in patients with cancer receiving platinum-based therapy. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 3144–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmorsy, E.A.; Saber, S.; Hamad, R.S.; Abdel-Reheim, M.A.; El-Kott, A.F.; AlShehri, M.A.; Morsy, K.; Salama, S.A.; Youssef, M.E. Advances in understanding cisplatin-induced toxicity: Molecular mechanisms and protective strategies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 203, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Du, J.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, C.; Dai, K. Cisplatin induces platelet apoptosis through the ERK signaling pathway. Thromb. Res. 2012, 130, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, D. Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: Literature review. Discov. Oncol. 2023, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraj, A.; Syed, M.P.; Low, C.A.; Owonikoko, T.K. Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity: A Concise Review of the Burden, Prevention, and Interception Strategies. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Guo, W.; Yu, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhou, M.; Xiang, K.; Niu, K.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, G.; An, Z.; et al. Reduction-sensitive platinum (IV)-prodrug nano-sensitizer with an ultra-high drug loading for efficient chemo-radiotherapy of Pt-resistant cervical cancer in vivo. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H.; Kuo, M.T. Role of glutathione in the regulation of Cisplatin resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Met. Based Drugs 2010, 2010, 430939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Ali-Osman, F. Glutathione-associated cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) metabolism and ATP-dependent efflux from leukemia cells. Molecular characterization of glutathione-platinum complex and its biological significance. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 20116–20125. [Google Scholar]

- Ravera, M.; Gabano, E.; McGlinchey, M.J.; Osella, D. Pt(IV) antitumor prodrugs: Dogmas, paradigms, and realities. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 2121–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, H. Current Developments in Pt(IV) Prodrugs Conjugated with Bioactive Ligands. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2018, 2018, 8276139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, C.; Giorgi, E.; Binacchi, F.; Cirri, D.; Gabbiani, C.; Pratesi, A. An overview of recent advancements in anticancer Pt (IV) prodrugs: New smart drug combinations, activation and delivery strategies. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 121388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canil, G.; Braccini, S.; Marzo, T.; Marchetti, L.; Pratesi, A.; Biver, T.; Gabbiani, C. Photocytotoxic Pt (iv) complexes as prospective anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 10933–10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iova, V.; Tincu, R.C.; Scrobota, I.; Tudosie, M.S. Pt(IV) Complexes as Anticancer Drugs and Their Relationship with Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, H.S.; Nukolova, N.V.; Kabanov, A.V.; Bronich, T.K. Nanocarriers for delivery of platinum anticancer drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1667–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faderin, E.; Iorkula, T.H.; Aworinde, O.R.; Awoyemi, R.F.; Awoyemi, C.T.; Acheampong, E.; Chukwu, J.U.; Agyemang, P.; Onaiwu, G.E.; Ifijen, I.H. Platinum nanoparticles in cancer therapy: Chemotherapeutic enhancement and ROS generation. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lei, G.; Wang, B.; Deng, Z.; Karges, J.; Xiao, H.; Tan, D. Encapsulation of Platinum Prodrugs into PC7A Polymeric Nanoparticles Combined with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Therapeutically Enhanced Multimodal Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy by Activation of the STING Pathway. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2205241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, H.; Gao, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, J.; Song, H.; Han, H. Disulfide-containing polymer delivery of C527 and a Platinum(IV) prodrug selectively inhibited protein ubiquitination and tumor growth on cisplatin resistant and patient-derived liver cancer models. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 18, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgovan, A.I.; Boia, E.R.; Motofelea, A.C.; Orasan, A.; Negru, M.C.; Guran, K.; Para, D.M.; Sandu, D.; Ciocani, S.; Sitaru, A.M.; et al. Advances in Nanotechnology-Based Cisplatin Delivery for ORL Cancers: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Tong, W.; Jiang, M.; Liu, H.; Meng, C.; Wang, K.; Mu, X. Mitochondria-Targeted Multifunctional Nanoprodrugs by Inhibiting Metabolic Reprogramming for Combating Cisplatin-Resistant Lung Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 21156–21170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafees, M.; Hanif, M.; Muhammad Asif Khan, R.; Faiz, F.; Yang, P. A Dual Action Platinum(IV) Complex with Self-assembly Property Inhibits Prostate Cancer through Mitochondrial Stress Pathway. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Foda, M.F.; Dai, X.; Han, H. Ultrasmall Peptide-Coated Platinum Nanoparticles for Precise NIR-II Photothermal Therapy by Mitochondrial Targeting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 39434–39443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Bi, Z.; Yang, H.; Lu, W.; Lu, T.; Qian, R.; Yang, X.; et al. Mitochondrial-Targeted Multifunctional Platinum-Based Nano “Terminal-Sensitive Projectile” for Enhanced Cancer Chemotherapy Efficacy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 8711–8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Deng, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xie, K.; Shi, P.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Shi, J.; et al. An erythrocyte-delivered photoactivatable oxaliplatin nanoprodrug for enhanced antitumor efficacy and immune response. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14353–14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Shi, J.; Gao, H.; Leong, W.S.; Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Li, P.; et al. Blood-triggered generation of platinum nanoparticle functions as an anti-cancer agent. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezar-Almahdi, E.; Heidari, R.; Ghasemi, S.; Mohammadi-Samani, S.; Farjadian, F. Integrin receptor mediated pH-responsive nano-hydrogel based on histidine-modified poly(aminoethyl methacrylamide) as targeted cisplatin delivery system. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 62, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkesh, K.; Heidari, R.; Iranpour, P.; Azarpira, N.; Ahmadi, F.; Mohammadi-Samani, S.; Farjadian, F. Theranostic Hyaluronan Coated EDTA Modified Magnetic Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Targeted Delivery of Cisplatin. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 77, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Nie, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, H. A Trisulfide Bond Containing Biodegradable Polymer Delivering Pt(IV) Prodrugs to Deplete Glutathione and Donate H2S to Boost Chemotherapy and Antitumor Immunity. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 7852–7867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, H.; Li, T.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, H.; Xu, M.; Bi, W. Combination of IDO inhibitors and platinum(IV) prodrugs reverses low immune responses to enhance cancer chemotherapy and immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wei, D.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, K.; Sun, Y. Osteosarcoma-targeting PtIV prodrug amphiphile for enhanced chemo-immunotherapy via Ca2+ trapping. Acta Biomater. 2025, 193, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wei, D.; Wang, B.; Tang, D.; Cheng, A.; Xiao, S.; Yu, Y.; Huang, W. NIR-II light evokes DNA cross-linking for chemotherapy and immunogenic cell death. Acta Biomater. 2023, 160, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, Á.-P.; Iglesias-Anciones, L.; Vaquero-González, J.J.; Piñol, R.; Criado, J.J.; Rodriguez, E.; Juanes-Velasco, P.; García-Vaquero, M.L.; Arias-Hidalgo, C.; Orfao, A.; et al. Enhancement of Tumor Cell Immunogenicity and Antitumor Properties Derived from Platinum-Conjugated Iron Nanoparticles. Cancers 2023, 15, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.P.; He, X.D.; Zhang, Q.F.; Qi, Y.X.; Zhou, D.F.; Xie, Z.G.; Li, X.Y.; Huang, Y.B. Synergistic enhancement of immunological responses triggered by hyperthermia sensitive Pt NPs via NIR laser to inhibit cancer relapse and metastasis. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, K.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Lin, W. Immunogenic Bifunctional Nanoparticle Suppresses Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 in Cancer and Dendritic Cells to Enhance Adaptive Immunity and Chemo-Immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 5152–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Zhu, Z.Z.; He, X.R.; Zou, Y.H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Liu, H.M.; Qiao, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.Y. NIR Light and GSH Dual-Responsive Upconversion Nanoparticles Loaded with Multifunctional Platinum(IV) Prodrug and RGD Peptide for Precise Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 40753–40766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisha; Pal, P.; Das, P.; Upadhyay, V.R. Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems: From Concept to Clinical Translation. In Next-Generation Drug Delivery Systems. Methods in Pharmacology and Toxicology, 1st ed.; Pathak, A., Singh, S.P., Eds.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Liu, G.; Yin, X. Facile construction of drugs loaded lipid-coated calcium carbonate as a promising pH-Dependent drug delivery system for thyroid cancer treatment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; He, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y. Dual-sensitive dual-prodrug nanoparticles with light-controlled endo/lysosomal escape for synergistic photoactivated chemotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 7115–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, G.; Ding, J.; Xie, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Q. Stimuli-Responsive Nodal Dual-Drug Polymer Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 5181–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Lu, W.; Fu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, T.; Xin, Y.; Xie, Z.; et al. Sequential dual-locking strategy using photoactivated Pt(IV)-based metallo-nano prodrug for enhanced chemotherapy and photodynamic efficacy by triggering ferroptosis and macrophage polarization. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 3251–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzei, L.F.; Martínez, Á.; Trevisan, L.; Rosa-Gastaldo, D.; Cortajarena, A.L.; Mancin, F.; Salassa, L. Toward supramolecular nanozymes for the photocatalytic activation of Pt(IV) anticancer prodrugs. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10461–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Noble, G.T.; Stefanick, J.F.; Qi, R.; Kiziltepe, T.; Jing, X.; Bilgicer, B. Photosensitive Pt(IV)-azide prodrug-loaded nanoparticles exhibit controlled drug release and enhanced efficacy in vivo. J. Control Release 2014, 173, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, G.; Sadhukhan, T.; Banerjee, S.; Tang, D.; Zhang, H.; Cui, M.; Montesdeoca, N.; Karges, J.; Xiao, H. Reduction of Platinum(IV) Prodrug Hemoglobin Nanoparticles with Deeply Penetrating Ultrasound Radiation for Tumor-Targeted Therapeutically Enhanced Anticancer Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202301074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Luo, C.; Shen, N.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X. Ultrasound irradiation-induced superoxide anion radical mediates the reduction of tetravalent platinum prodrug for anti-tumor therapy. CCS Chem. 2025, 7, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Gong, S.; Yu, Z. Nano-assembly of ursolic acid with platinum prodrug overcomes multiple deactivation pathways in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 4110–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.Y.; Zhu, Y.X.; Jia, H.R.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gu, R.; Li, C.; Wu, F.G. Platinum-Coordinated Dual-Responsive Nanogels for Universal Drug Delivery and Combination Cancer Therapy. Small 2022, 18, 2203260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Ji, X.; Joseph, J.; Tang, Z.; Ouyang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Kong, N.; Joshi, N.; Farokhzad, O.C.; et al. Stanene-Based Nanosheets for β-Elemene Delivery and Ultrasound-Mediated Combination Cancer Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 7155–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, P.; Xu, X.; Ran, L.; Zhang, L.; Tian, G.; Zhang, G. Amorphous ferric oxide-coating selenium core-shell nanoparticles: A self-preservation Pt(IV) platform for multi-modal cancer therapies through hydrogen peroxide depletion-mediated anti-angiogenesis, apoptosis and ferroptosis. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 11600–11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; He, T.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Hao, J.; Huang, P.; Cui, J. Polypeptide-Based Theranostics with Tumor-Microenvironment-Activatable Cascade Reaction for Chemo-ferroptosis Combination Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20271–20280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Sun, S.; Sun, R.; Cui, G.; Hong, L.; Rao, B.; Li, A.; Yu, Z.; Kan, Q.; Mao, Z. A Metal-Polyphenol-Coordinated Nanomedicine for Synergistic Cascade Cancer Chemotherapy and Chemodynamic Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Calero-Pérez, P.; Montpeyó, D.; Bruna, J.; Yuste, V.J.; Candiota, A.P.; Lorenzo, J.; Novio, F.; Ruiz-Molina, D. Intranasal Administration of Catechol-Based Pt(IV) Coordination Polymer Nanoparticles for Glioblastoma Therapy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.L.; Zhou, L.Y. Cetuximab-decorated and NIR-activated Nanoparticles Based on Platinum(IV)-prodrug: Preparation, Characterization and In-vitro Anticancer Activity in Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells. IJPR 2021, 20, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marotta, C.; Cirri, D.; Kanavos, I.; Ronga, L.; Lobinski, R.; Funaioli, T.; Giacomelli, C.; Barresi, E.; Trincavelli, M.L.; Marzo, T.; et al. Oxaliplatin(IV) Prodrugs Functionalized with Gemcitabine and Capecitabine Induce Blockage of Colorectal Cancer Cell Growth-An Investigation of the Activation Mechanism and Their Nanoformulation. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Du, X.F.; Liu, B.; Li, C.; Long, J.; Zhao, M.X.; Yao, Z.; Liang, X.J.; Lai, Y. Engineering Supramolecular Nanomedicine for Targeted Near Infrared-triggered Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Potentiate Cisplatin for Efficient Chemophototherapy. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Xue, X.; Liu, S. NIR and Reduction Dual-Sensitive Polymeric Prodrug Nanoparticles for Bioimaging and Combined Chemo-Phototherapy. Polymers 2022, 14, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, L.; Rong, G.; Weng, Y.; et al. Near-Infrared Light Irradiation Induced Mild Hyperthermia Enhances Glutathione Depletion and DNA Interstrand Cross-Link Formation for Efficient Chemotherapy. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14831–14845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, B.; Malhotra, M.; Jayakannan, M. Fluorescent ABC-Triblock Polymer Nanocarrier for Cisplatin Delivery to Cancer Cells. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Chang, Y.; Xu, J.F.; Zhang, X. A Polymeric Nanoparticle to Co-Deliver Mitochondria-Targeting Peptides and Pt(IV) Prodrug: Toward High Loading Efficiency and Combination Efficacy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202402291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Rong, G.; Wang, W.; Kang, X.; et al. Breaking the Intracellular Redox Balance with Diselenium Nanoparticles for Maximizing Chemotherapy Efficacy on Patient-Derived Xenograft Models. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16984–16996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xu, S.; Huang, W.; Yan, D. Light-responsive nanodrugs co-self-assembled from a PEG-Pt(IV) prodrug and doxorubicin for reversing multidrug resistance in the chemotherapy process of hypoxic solid tumors. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 3901–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wei, D.; Bing, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H. A Polyplatin with Hands-Holding Near-Infrared-II Fluorophores and Prodrugs at a Precise Ratio for Tracking Drug Fate with Realtime Readout and Treatment Feedback. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2402452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.; Xue, X.; Xu, B.; Li, T.; Chen, Z. Synthesis Characterization of Platinum (IV) Complex Curcumin Backboned Polyprodrugs: In Vitro Drug Release Anticancer Activity. Polymers 2020, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Peiro, J.I.; Ortega-Liebana, M.C.; Adam, C.; Lorente-Macías, Á.; Travnickova, J.; Patton, E.E.; Guerrero-López, P.; Garcia-Aznar, J.M.; Hueso, J.L.; Santamaria, J.; et al. Dendritic Platinum Nanoparticles Shielded by Pt-S PEGylation as Intracellular Reactors for Bioorthogonal Uncaging Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202424037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, H.; Qing, G.; Fu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Shu, W.; He, S.; et al. Bioorthogonal Chemistry-Guided Inhalable Nanoprodrug to Circumvent Cisplatin Resistance in Orthotopic Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 32103–32117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Ji, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Huang, Z. One Stone Two Birds: Redox-Sensitive Colocalized Delivery of Cisplatin and Nitric Oxide Through Cascade Reactions. JACS Au 2022, 2, 2339–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Triguero, P.; Lorenzo, J.; Candiota, A.P.; Arús, C.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Novio, F. Platinum-Based Nanoformulations for Glioblastoma Treatment: The Resurgence of Platinum Drugs? Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, D.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Skvortsov, D.; Trigub, A.; Markova, A.; Nikitina, V.; Ul’yanovskiy, N.; Shtil’, A.; Semkina, A.; et al. Biotinylated Pt(IV) prodrugs with elevated lipophilicity and cytotoxicity. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, M.; Gabano, E.; Perin, E.; Rangone, B.; Bonzani, D.; Osella, D. Can the Self-Assembling of Dicarboxylate Pt(IV) Prodrugs Influence Their Cell Uptake? Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021, 2021, 9489926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Ammar, A.; Raveendran, R.; Gibson, D.; Nassar, T.; Benita, S. A Lipophilic Pt(IV) Oxaliplatin Derivative Enhances Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9035–9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, S.; Li, J.; Cao, Z.; Yang, X. Precise Depletion of Tumor Seed and Growing Soil with Shrinkable Nanocarrier for Potentiated Cancer Chemoimmunotherapy. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 4636–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavas, S.; Quazi, S.; Karpiński, T.M. Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy: Current Progress and Challenges. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, X.; Zhu, W.; Huang, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, H.; Jin, L.; Pu, J.J.; Xie, X.; She, J.; Lui, V.W.Y.; et al. Microneedles Loaded with Anti-PD-1–Cisplatin Nanoparticles for Synergistic Cancer Immuno-Chemotherapy. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 18885–18898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafeez, M.N.; Celia, C.; Petrikaite, V. Challenges towards Targeted Drug Delivery in Cancer Nanomedicines. Processes 2021, 9, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Fan, J.; Yan, J.; Liu, C.; Cao, J.; Xu, C.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, H. Nuclear-Targeting Lipid PtIV Prodrug Amphiphile Cooperates with siRNA for Enhanced Cancer Immunochemotherapy by Amplifying Pt-DNA Adducts and Reducing Phosphatidylserine Exposure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, T.; Huang, L.; Yang, M.; Zhu, G. Self-assembled Lipid Nanoparticles for Ratiometric Codelivery of Cisplatin and siRNA Targeting XPF to Combat Drug Resistance in Lung Cancer. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, K.; Zhang, X.Q.; Pridgen, E.M.; Park, G.Y.; Cui, D.S.; Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Kantoff, P.W.; Lippard, S.J.; et al. Enhancing tumor cell response to chemotherapy through nanoparticle-mediated codelivery of siRNA and cisplatin prodrug. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18638–18643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Ghosh, B.; Biswas, S. Human Serum Albumin-Oxaliplatin (Pt(IV)) prodrug nanoparticles with dual reduction sensitivity as effective nanomedicine for triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Li, S.; Wu, W.; Zhao, L.; Xie, P.; Yang, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Abplatin(IV) inhibited tumor growth on a patient derived cancer model of hepatocellular carcinoma and its comparative multi-omics study with cisplatin. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Luo, W.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, L.; Gao, L.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F. Human Serum Albumin-Platinum(II) Agent Nanoparticles Inhibit Tumor Growth Through Multimodal Action Against the Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).