Folate-Functionalized ROS-Scavenging Covalent Organic Framework for Oral Targeted Delivery of Ferulic Acid in Ulcerative Colitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Materials

2.2. Micro γ-CD-MOF Preparation

2.3. Synthesis of ROS-Sensitive Crosslinked Cyclodextrin Framework

2.4. Ferulic Acid Incorporation

2.5. Folic Acid Functionalized ROS-Sensitive COF

2.6. Physicochemical Characterization

2.7. In Vitro Antioxidant Capability of COF-FA

2.8. In Vitro Release Study

2.9. Cell Viability Assay

2.10. In Vivo Study

2.10.1. Animal Grouping and Study Design

2.10.2. Disease Activity Index (DAI) Evaluation

2.10.3. Determination of Colon Length and Spleen Index

2.10.4. Analysis of Colon Tissue Pathology Sections

2.10.5. Serum Inflammatory Cytokine Measurement

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

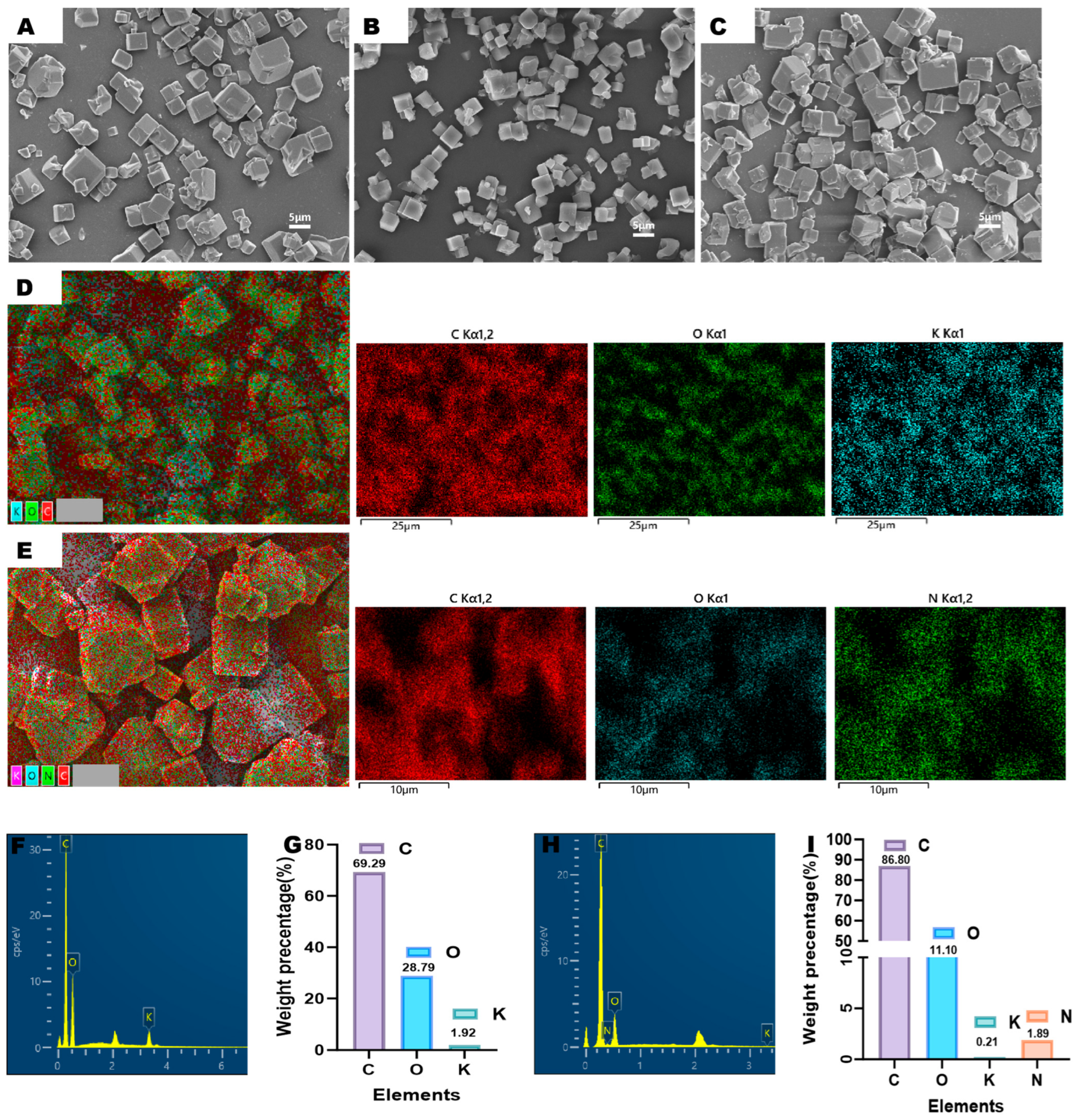

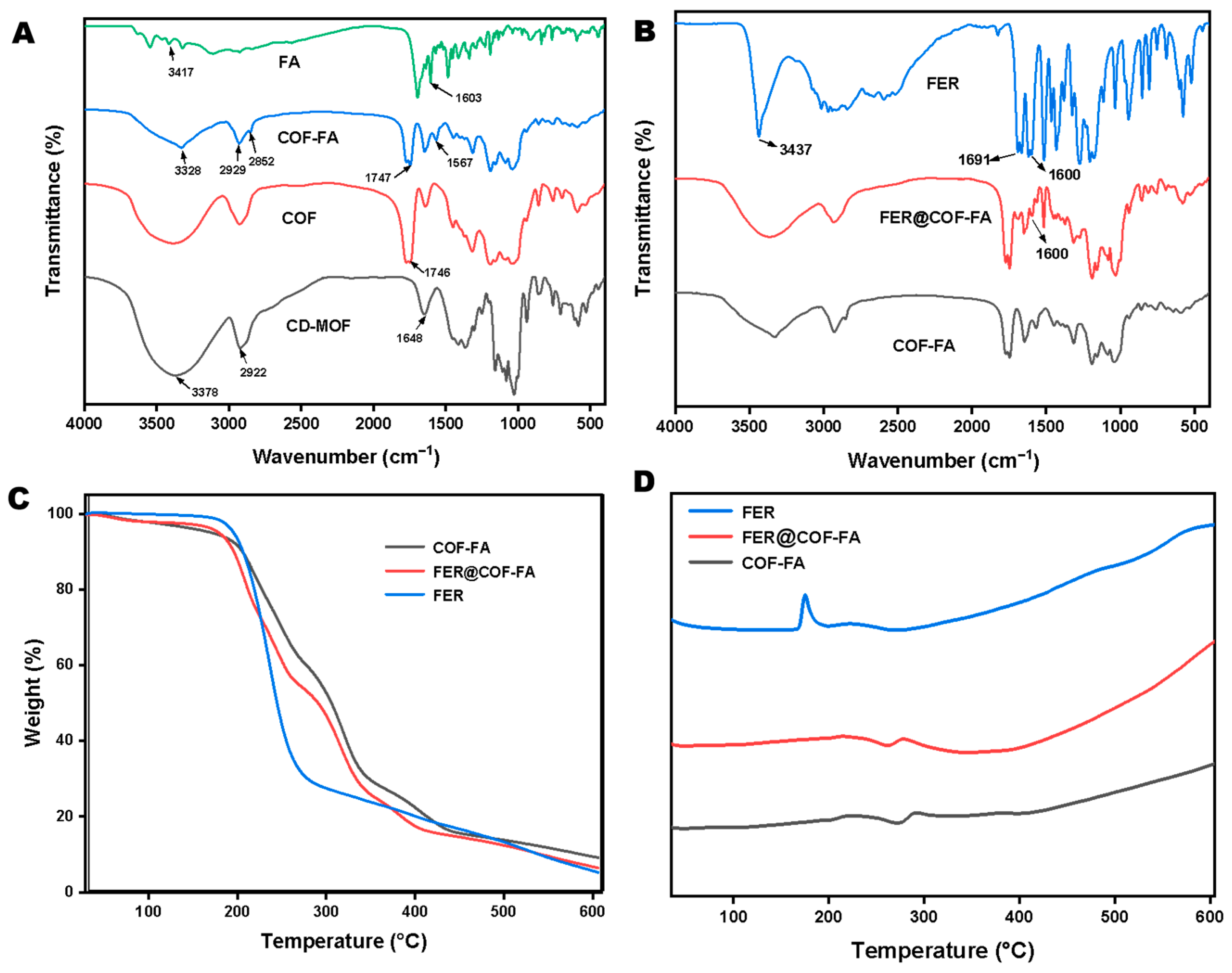

3.1. Characterization

3.2. Evaluation of In Vitro H2O2 Scavenging Ability of COF-FA

3.3. FER In Vitro Release Result

3.4. Cytotoxicity of COF-FA and FER@COF-FA Carrier

3.5. In Vivo Study

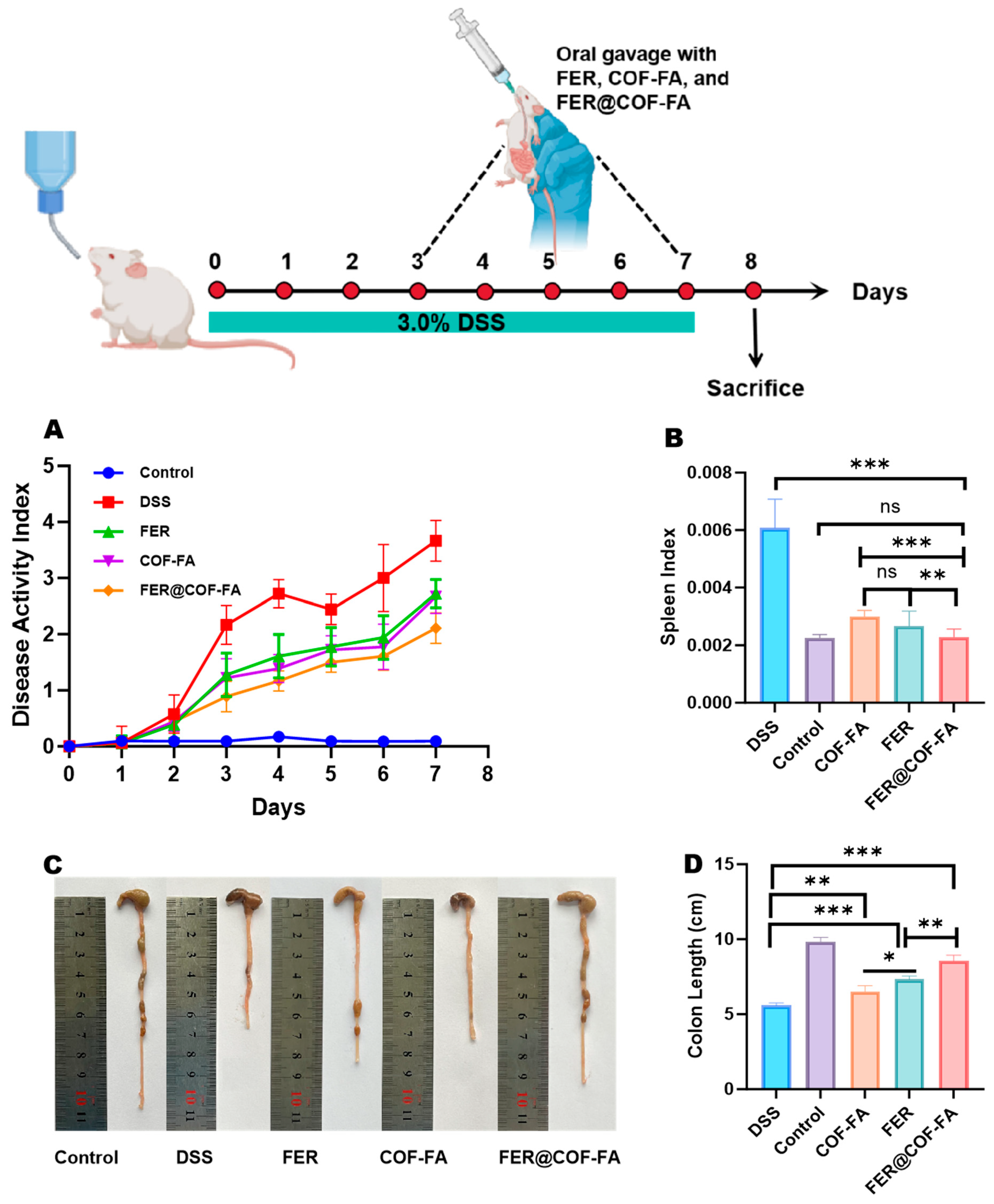

3.5.1. Therapeutic Efficacy in DSS-Induced Colitis

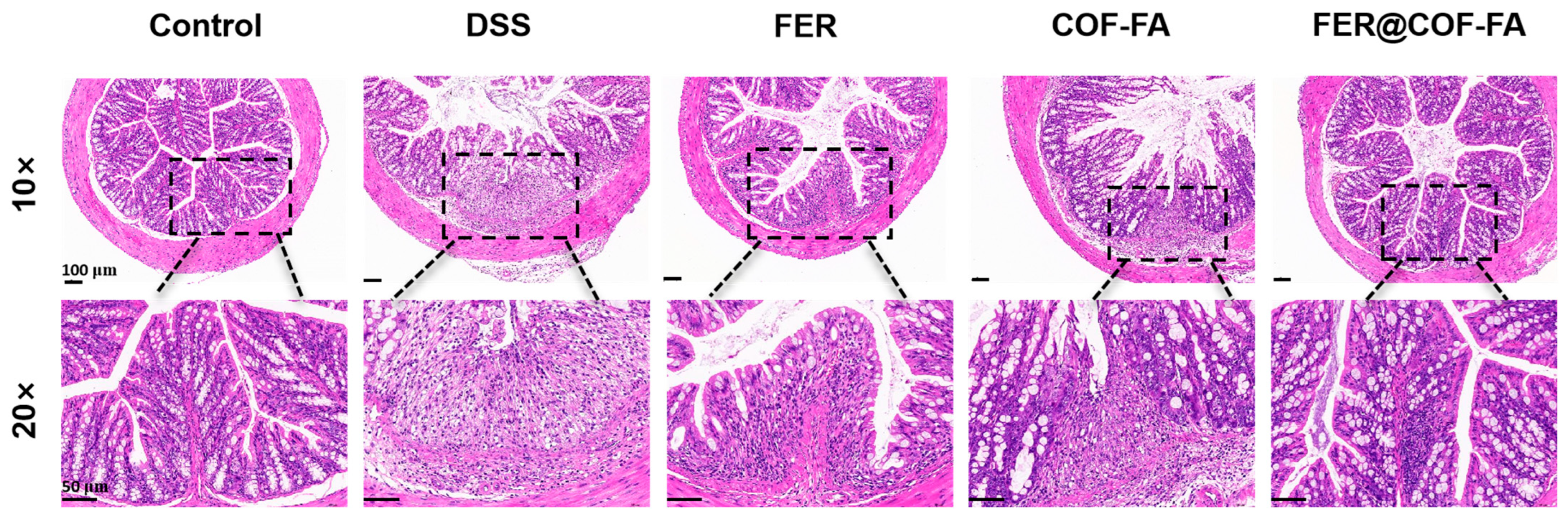

3.5.2. Pathological Changes in the Colonic Tissue of Mice

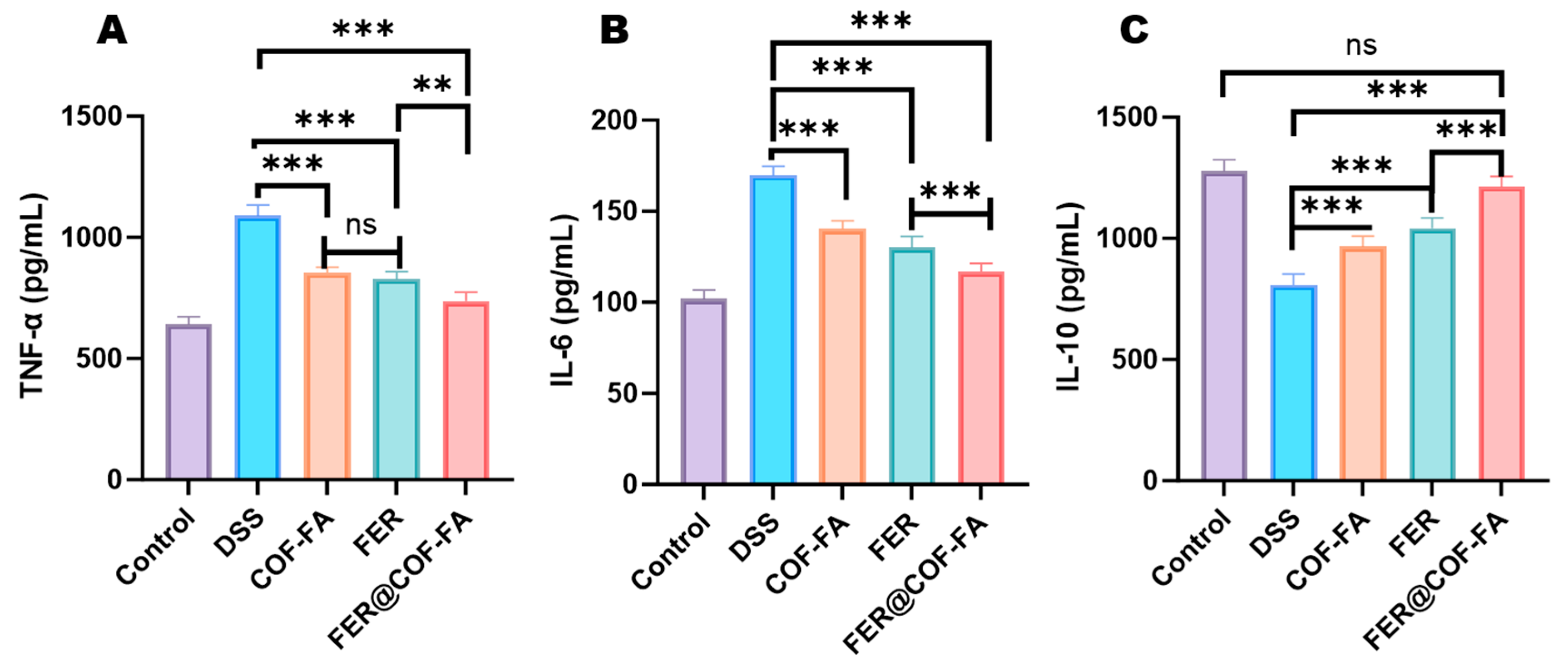

3.5.3. Effect of Inflammatory Factors in Mice Serum

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tatiya-aphiradee, N.; Chatuphonprasert, W.; Jarukamjorn, K. Immune Response and Inflammatory Pathway of Ulcerative Colitis. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, A.; Herrero-Fernandez, B.; Gomez-Bris, R.; Sánchez-Martinez, H.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Innate Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Goggolidou, P. Ulcerative Colitis: Understanding Its Cellular Pathology Could Provide Insights into Novel Therapies. J. Inflamm. 2020, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Jain, P. Ajazuddin Recent Advances in the Therapeutics and Modes of Action of a Range of Agents Used to Treat Ulcerative Colitis and Related Inflammatory Conditions. Inflammopharmacol 2025, 33, 4965–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J.; Sturm, A. Current Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3204–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack; Williams; Stevenson; Logan. Immunosuppressive Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis: Results of a Nation-wide Survey among Consultant Physician Members of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 13, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaemsupaphan, T.; Arzivian, A.; Leong, R.W. Comprehensive Care of Ulcerative Colitis: New Treatment Strategies. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, S.; Qian, D.; Duan, J. Excessive Apoptosis in Ulcerative Colitis: Crosstalk Between Apoptosis, ROS, ER Stress, and Intestinal Homeostasis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Fan, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, F.; et al. Selective Oxidative Protection Leads to Tissue Topological Changes Orchestrated by Macrophage during Ulcerative Colitis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Meng, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Z.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, K.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Nanocarrier Ameliorates Murine Colitis by Intervening Colonic Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 1383–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, S.; Chelvam, V.; Low, P.S. Comparison of Nanoparticle Penetration into Solid Tumors and Sites of Inflammation: Studies Using Targeted and Nontargeted Liposomes. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Xia, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, P.; Jin, Y. Role of Macrophage in Nanomedicine-Based Disease Treatment. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Sung, J.; Garg, P.; Zhang, M.; Merlin, D. Oral Targeted Delivery by Nanoparticles Enhances Efficacy of an Hsp90 Inhibitor by Reducing Systemic Exposure in Murine Models of Colitis and Colitis-Associated Cancer. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, R. Plant-Derived Exosomes as a Drug-Delivery Approach for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Xi, R.; Long, D. Advances in Oral Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Using Protein-Based Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Deliv. 2025, 32, 2544689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, G.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.J. Reactive-Oxygen-Species-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems: Promises and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1600124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, N.; Gambhir, K.; Kumar, S.; Gangenahalli, G.; Verma, Y.K. Interplay of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Tissue Engineering: A Review on Clinical Aspects of ROS-Responsive Biomaterials. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 16790–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; He, Z. ROS-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems for Biomedical Applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nidhi; Rashid, M.; Kaur, V.; Hallan, S.S.; Sharma, S.; Mishra, N. Microparticles as Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: A Brief Review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gvozdeva, Y.; Staynova, R. pH-Dependent Drug Delivery Systems for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lan, H.; Jin, K.; Chen, Y. Responsive Nanosystems for Targeted Therapy of Ulcerative Colitis: Current Practices and Future Perspectives. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2219427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.; Si, X.; Zhang, M.; Merlin, D. Oral Administration of pH-Sensitive Curcumin-Loaded Microparticles for Ulcerative Colitis Therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 135, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhtiar, M.; Ghasemi-Dehnoo, M.; Azadegan-Dehkordi, F.; Bagheri, N. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of Ferulic Acid and Quinic Acid on Acetic Acid-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, e70169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guan, Y.; Yang, L.; Fang, H.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Yan, G.; Kong, L.; Wang, X. Ferulic Acid as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent: Insights into Molecular Mechanisms, Pharmacokinetics and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Luo, Y. Chitosan-Based Oral Colon-Specific Delivery Systems for Polyphenols: Recent Advances and Emerging Trends. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 7328–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.D.; Singh, D. A Critical Appraisal on Ferulic Acid: Biological Profile, Biopharmaceutical Challenges and Nano Formulations. Health Sci. Rev. 2022, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, J.R.; Rizwanullah, M. Ferulic Acid: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e68063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Wu, L.; Sun, H.; Wu, D.; Wang, C.; Ren, X.; Shao, Q.; York, P.; Tong, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. Antioxidant Biodegradable Covalent Cyclodextrin Frameworks as Particulate Carriers for Inhalation Therapy against Acute Lung Injury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 38421–38435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, D.; Wang, M.; Bai, J.; Wang, N.; Bian, W.; Zhou, B. Polyrotaxanated Covalent Organic Frameworks Based on β-Cyclodextrin towards High-Efficiency Synergistic Inactivation of Bacterial Pathogens. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Framework Design Principles and Functionalization for Biomedical Application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 364, 123684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, M.G.; Huang, S.; Qiao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L. Luteolin Stabilized in Nanosheet and Cubic γ-Cyclodextrin-Based Metal Organic Framework for Enhanced Bioavailability and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Chen, T.; Chi, X.; Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Zhu, B.; Hu, J. Targeted Quercetin Delivery Nanoplatform via Folic Acid-Functionalized Metal-Organic Framework for Alleviating Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcer. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Shi, Y.; Hou, J.; Peng, J.; Pan, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, J. Establishment and Validation of HPLC Methods for the Determination of Folic Acid and Parabens Antimicrobial Agents on Folic Acid Oral Solution. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhu, X.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.-F.; Wang, D.; Wen, W.; Liang, J.; et al. Ambient Synthesis of Porphyrin-Based Fe-Covalent Organic Frameworks for Efficient Infected Skin Wound Healing. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 3671–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, N.; Inoue, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Murata, I.; Meiyan, X.; Takayama, J.; Sakamoto, T.; Okazaki, M.; Kanamoto, I. Improvement of the Solubility and Evaluation of the Physical Properties of an Inclusion Complex Formed by a New Ferulic Acid Derivative and γ-Cyclodextrin. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12073–12080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, M.; Hirai, F.; Takatsu, N.; Hisabe, T.; Takada, Y.; Beppu, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Naganuma, M.; Ohtsuka, K.; Watanabe, K.; et al. A Review on the Current Status and Definitions of Activity Indices in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: How to Use Indices for Precise Evaluation. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, L.; Zhou, P.; Ding, H.; Ge, X.; Guo, T.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J. Facile Synthesis and Size Control of 2D Cyclodextrin-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks Nanosheet for Topical Drug Delivery. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2020, 37, 2000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, L.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Z.; Garba, B.M.; Gao, G.; He, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. CD-MOFs Crystal Transformation from Dense to Highly Porous Form for Efficient Drug Loading. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 3888–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Xu, H.; Nie, Q.; Jia, B.; Bao, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Triggered Cleavage of Thioketal-Containing Supramolecular Nanoparticles for Inflammation-Targeted Oral Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2411979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamipour, S.; Sadjadi, M.S.; Farhadyar, N. Fabrication and Spectroscopic Studies of Folic Acid-Conjugated Fe3O4@Au Core–Shell for Targeted Drug Delivery Application. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 148, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y. Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro Release of Folic Acid-Conjugated Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Methotrexate for Targeted Delivery. Polym. Bull. 2012, 68, 1707–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummert, S.V.; Saini, H.; Hussain, M.Z.; Yadava, K.; Jayaramulu, K.; Casini, A.; Fischer, R.A. Cyclodextrin Metal–Organic Frameworks and Derivatives: Recent Developments and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5175–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, G.S.N.; Pereira, M.A.V.; Ostrosky, E.A.; Barbosa, E.G.; De Moura, M.D.F.V.; Ferrari, M.; Aragão, C.F.S.; Gomes, A.P.B. Compatibility Study between Ferulic Acid and Excipients Used in Cosmetic Formulations by TG/DTG, DSC and FTIR. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Teng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J. The Intestinal Delivery Systems of Ferulic Acid: Absorption, Metabolism, Influencing Factors, and Potential Applications. Food Front. 2024, 5, 1126–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, S.; Putt, K.S.; Low, P.S. Folate-Targeted Dendrimers Selectively Accumulate at Sites of Inflammation in Mouse Models of Ulcerative Colitis and Atherosclerosis. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3082–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, S.; Chelvam, V.; Ayala-López, W.; Putt, K.S.; Low, P.S. Selective Liposome Targeting of Folate Receptor Positive Immune Cells in Inflammatory Diseases. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Guo, S.; Liu, C. Effects of Folate-Chicory Acid Liposome on Macrophage Polarization and TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Ulcerative Colitis Mouse. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelderhouse, L.E.; Mahalingam, S.; Low, P.S. Predicting Response to Therapy for Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases Using a Folate Receptor-Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescent Imaging Agent. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2016, 18, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Aitken, J.D.; Malleshappa, M.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis in Mice. CP Immunol. 2014, 104, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, J.; Qiao, Z.; Huang, S.; Bello, M.G.; Chen, L. Folate-Functionalized ROS-Scavenging Covalent Organic Framework for Oral Targeted Delivery of Ferulic Acid in Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101263

Xue J, Qiao Z, Huang S, Bello MG, Chen L. Folate-Functionalized ROS-Scavenging Covalent Organic Framework for Oral Targeted Delivery of Ferulic Acid in Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(10):1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101263

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Jin, Zifan Qiao, Shiyu Huang, Mubarak G. Bello, and Lihua Chen. 2025. "Folate-Functionalized ROS-Scavenging Covalent Organic Framework for Oral Targeted Delivery of Ferulic Acid in Ulcerative Colitis" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 10: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101263

APA StyleXue, J., Qiao, Z., Huang, S., Bello, M. G., & Chen, L. (2025). Folate-Functionalized ROS-Scavenging Covalent Organic Framework for Oral Targeted Delivery of Ferulic Acid in Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceutics, 17(10), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101263