Abstract

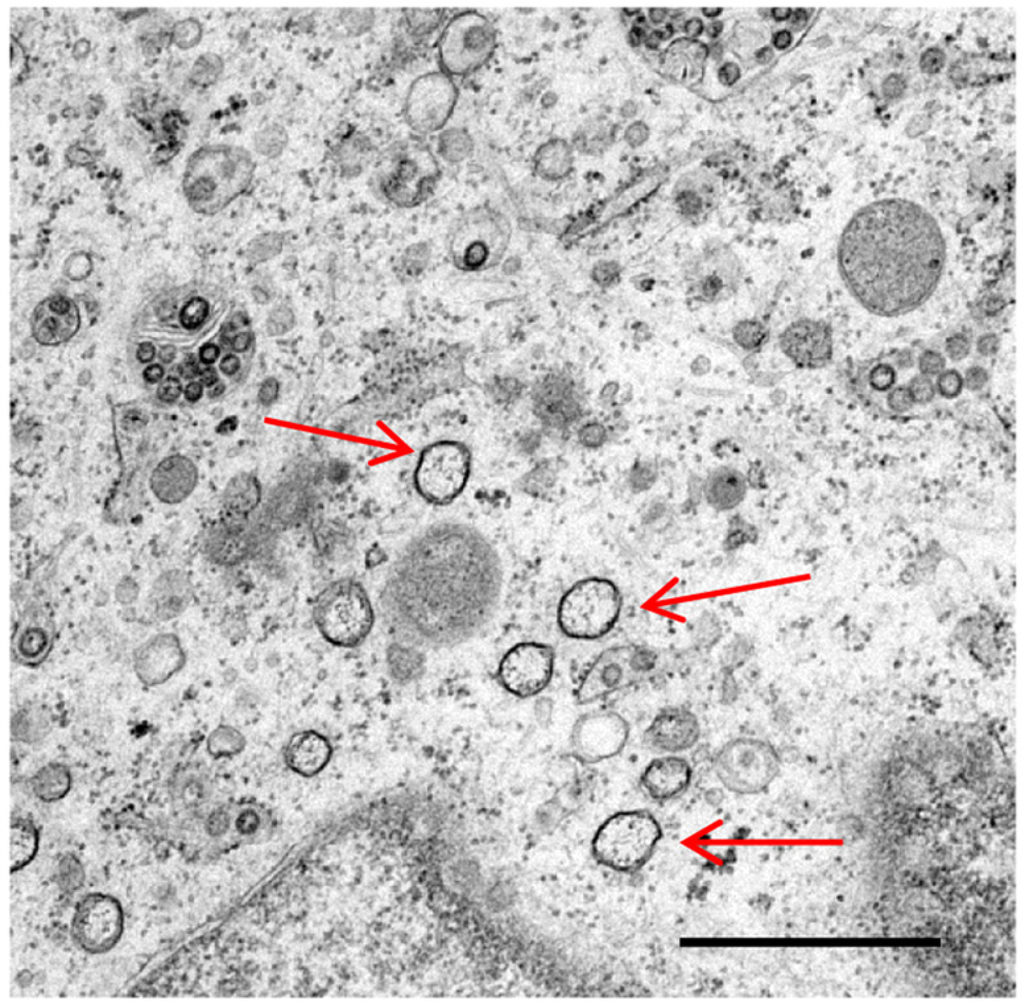

Coronaviruses are single stranded, positive sense RNA viruses, which induce the rearrangement of cellular membranes upon infection of a host cell. This provides the virus with a platform for the assembly of viral replication complexes, improving efficiency of RNA synthesis. The membranes observed in coronavirus infected cells include double membrane vesicles. By nature of their double membrane, these vesicles resemble cellular autophagosomes, generated during the cellular autophagy pathway. In addition, coronavirus infection has been demonstrated to induce autophagy. Here we review current knowledge of coronavirus induced membrane rearrangements and the involvement of autophagy or autophagy protein microtubule associated protein 1B light chain 3 (LC3) in coronavirus replication.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are single stranded positive sense RNA viruses belonging to the order Nidovirales, and are known to infect a variety of hosts. Several human coronaviruses have been identified, causing mainly mild respiratory infections, with the exception of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). In addition, coronavirus infections have an economic impact on livestock industries worldwide. The avian coronavirus, infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), causes infectious bronchitis (IB), a mild respiratory infection, but as a consequence is responsible for serious effects on the global poultry industries due to poor weight gain in broiler chickens as well as reduced egg production and egg quality in layers. In addition, some strains of IBV are nephropathogenic whilst others result in severe pathology in the reproductive organs. Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) causes respiratory infection and diarrhoea in cattle, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PEDV) cause diarrhoea in pigs and porcine haemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (PHEV) causes vomiting and wasting disease in pigs.

3. Autophagy

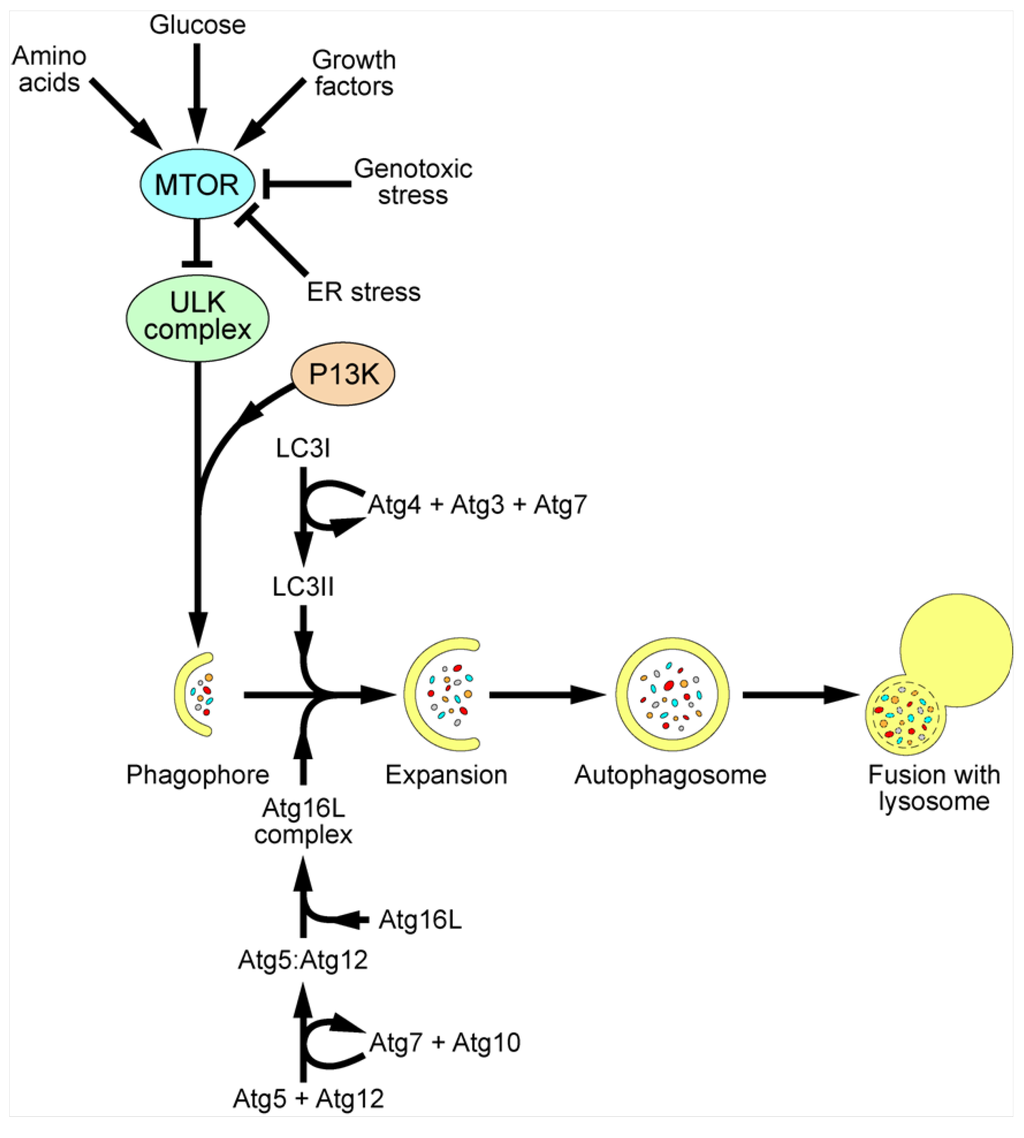

Autophagy is a cellular pathway for self-degradation. The pathway allows a cell to degrade long-lived proteins, aggregated proteins and organelles during periods of starvation to provide nutrients for continued cellular processes, as well as playing an important role in cellular homeostasis, ageing and development [11,12,13,14,15]. In addition, dysregulation of autophagy plays an important role in the development of some cancers [16]. During autophagy, regions of the cytoplasm become engulfed into double membrane bound vesicles termed autophagosomes. These vesicles then fuse with late endosomes/lysosomes, where the contents are degraded by lysosomal proteases (Figure 2). For detailed reviews of autophagy signaling, see [17,18]. The major control complex for autophagy is MTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) which, when active, inhibits initiation of the pathway. MTOR senses amino acid levels, as well as levels of growth factors and glucose and genotoxic and ER stress. Under resting conditions, MTOR phosphorylates and inactivates the ULK complex, comprising unc-51-like kinase 1/2 (ULK1/2), focal adhesion kinase family-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200) and mammalian ATG13. Under stimulatory conditions, MTOR is inactivated; the ULK complex becomes hypophosphorylated and relocates to the site of formation of the autophagosome, the phagophore. Formation of the autophagosome proceeds by addition of new membrane to the phagophore, as opposed to budding from an existing membrane, in a poorly understood process. However, a number of proteins are known to be required. Recruitment of these proteins occurs via the generation of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) by the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (PI3K), including BECN1 (Beclin 1). Inhibition of PI3K activity using drugs such as wortmannin and 3-methyladenine (3-MA), and sequestration of BECN1 by antiapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 (Bcl2) all inhibit autophagy.

Elongation of the autophagosome membrane and formation of the complete autophagosome requires the recruitment of 2 ubiquitin-like (Ubl) conjugation systems. In the first, ATG12 becomes conjugated to ATG5 in a process requiring the E1-like enzyme ATG7 and the E2-like enzyme ATG10. ATG12-ATG5 then binds to ATG16L and forms a large complex known as the ATG16L complex. This complex localises to the phagophore and can determine the site of conjugation of the second Ubl system. In this second system, microtubule associated protein 1B light chain 3 (LC3) is initially cleaved by ATG4 near the C-terminus at position G120 to generate cytoplasmic LC3-I. This subsequently becomes lipidated with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in a process requiring ATG7 and another E2-like enzyme ATG3 to generate membrane tethered LC3-II [19]. LC3-II is inserted into both the inner and outer membranes of the autophagosome, and as such, remains associated with the autophagosome throughout the pathway [20,21]. As a result, LC3 has become an extremely valuable marker protein for studying autophagy.

Figure 2.

Schematic of mammalian autophagy pathway. MTOR is the major control complex for autophagy. MTOR senses levels of amino acids, glucose and growth factors, as well as genotoxic and ER stress. Upon stimulatory signals, MTOR becomes inactivated and the ULK complex becomes hypophosphorylated and relocalises to the phagophore, along with PIP3, produced by class III PI3K complexes. The Atg16L complex and LC3II are also recruited to the growing autophagosome, allowing expansion of the membrane and fusion to give a complete autophagosome, engulfing organelles, aggregated proteins and intracellular pathogens. The autophagosome then fuses with a lysosome, resulting in the degradation of the contents and recycling of nutrients into the cytoplasm.

In addition to its role in cellular homeostasis, autophagy has been shown to have a function in innate immunity by degrading intracellular pathogens, including viruses. Furthermore, autophagy plays a role in presenting pathogen components to the immune system [22,23,24,25]. Inhibition of autophagy has a positive effect on the replication or virulence of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) [26,27], Sindbis virus [28,29] and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [30]. In addition, the capsid protein of Sindbis virus was found to be specifically targeted to the autophagosome via an interaction with the autophagy cargo receptor, p62 [28]. However, many viruses have evolved mechanisms to evade autophagy by inhibiting the pathway, or diverting the process to benefit virus replication. Many viral proteins have been identified that inhibit formation of autophagosomes. For example, HSV1 protein ICP34.5 binds to BECN1 and inhibits autophagosome formation and Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and murine γ-herpesvirus (MHV-68) encode Bcl2 homologues to bind to and inhibit BECN1 [26,31,32]. KSHV also encodes another protein to block LC3 processing by inhibiting ATG3 [33]. Other viruses have developed mechanisms to inhibit fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) encoded protein Nef interacts with BECN1, inhibiting lysosomal fusion [34]. Influenza A virus protein M2 has also been shown to induce accumulation of autophagosomes as a result of inhibition of lysosomal fusion, possibly via an interaction with BECN1 [35]. Moreover, numerous viruses have been identified which require autophagy for optimal replication, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) [36], poliovirus [37], coxsackievirus, HIV-1 [38], hepatitis C virus (HCV) [39], Dengue virus [40,41] and Japanese encephalitis virus [42]. Finally, poliovirus subverts autophagy in order to generate membranous structures required for assembly of viral replication complexes [37,43]. For more detailed information about the role of autophagy in the replication cycles of viruses, see reviews [44,45,46,47,48,49].

5. Future Questions and Perspectives

Although mounting evidence suggests that autophagy is unlikely to play a role in the replication of coronaviruses and the generation of coronavirus replicative structures, several questions remain unanswered. Work performed so far focusses mainly of members of the betacoronaviruses, MHV and SARS-CoV. Detailed characterisation of the membrane structures induced in cells infected with alphacoronaviruses, like transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), or gammacoronaviruses, like IBV, needs to be performed. Although these viruses are related, it is possible that there are differences in the mechanisms of membrane rearrangement and the types of structures induced. In addition, the location of RTC assembly and the site of viral RNA transcription and replication need to be identified. The membranes induced in MHV and SARS-CoV infected cells are complex and how the different structures play a role in virus replication is currently unknown. Furthermore, the mechanism by which these rearrangements are generated is not understood. Whether MHV induced membranes are altered upon inhibition of ERAD tuning and which proteins might be involved in hijacking the pathway remains unknown. Moreover, whether this pathway is important for the replication of other coronaviruses is also unknown.

Recently the replication of IBV has been shown to induce autophagy in mammalian cells [55]. Furthermore, individual expression of IBV nsp6, as well as nsp6 homologues from other viruses in the Nidovirales order, has been shown to induce autophagy [55]. However, the mechanism by which this induction occurs is unknown. Whether nsp6 is responsible for inducing autophagy in the context of whole virus would also be interesting to discover. In addition, as IBV is restricted to avian species, would similar observations be made in a more natural host model? Finally, several studies have shown that coronavirus infection induces autophagy [9,50,51,52,54,55]. However, the pathway does not appear to be required for virus replication [52,53,55,56]. Therefore, is autophagy acting as a cellular defence to virus infection and does the virus have mechanisms to control this response?

Acknowledgements

PB and HJM were funded by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Grant BB/E01805X/1. In addition, HJM was supported by BBSRC funding directly to The Pirbright Institute and PB is funded by a LINK Consortium grant (LK0699) funded by BBSRC (BB/H01425X/1), Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA OD0720) and Pfizer Global Animal Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Lai, M.M.C.; Perlman, S.; Anderson, L.J. Coronaviridae. In Fields Virology; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philidelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 1305–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Posthuma, C.C.; Pedersen, K.W.; Lu, Z.; Joosten, R.G.; Roos, N.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Snijder, E.J. Formation of the arterivirus replication/transcription complex: A key role for nonstructural protein 3 in the remodeling of intracellular membranes. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4480–4491. [Google Scholar]

- Snijder, E.J.; van Tol, H.; Roos, N.; Pedersen, K.W. Non-structural proteins 2 and 3 interact to modify host cell membranes during the formation of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 985–994. [Google Scholar]

- Gadlage, M.J.; Sparks, J.S.; Beachboard, D.C.; Cox, R.G.; Doyle, J.D.; Stobart, C.C.; Denison, M.R. Murine hepatitis virus nonstructural protein 4 regulates virus-induced membrane modifications and replication complex function. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementz, M.A.; Kanjanahaluethai, A.; O'Brien, T.E.; Baker, S.C. Mutation in murine coronavirus replication protein nsp4 alters assembly of double membrane vesicles. Virology 2008, 375, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeijer, M.C.; Ulasli, M.; Vonk, A.M.; Reggiori, F.; Rottier, P.J.M.; de Haan, C.A.M. Mobility and interactions of coronavirus nonstructural protein 4. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4572–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoops, K.; Kikkert, M.; van den Worm, S.H.E.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; van der Meer, Y.; Koster, A.J.; Mommaas, A.M.; Snijder, E.J. Sars-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulasli, M.; Verheije, M.H.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Reggiori, F. Qualitative and quantitative ultrastructural analysis of the membrane rearrangements induced by coronavirus. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 844–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; van der Meer, Y.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.; Onderwater, J.J.M.; van der Meulen, J.; Koerten, H.K.; Mommaas, A.M. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5927–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeijer, M.C.; Vonk, A.M.; Monastyrska, I.; Rottier, P.J.M.; de Haan, C.A.M. Visualizing coronavirus rna synthesis in time by using click chemistry. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 5808–5816. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.X.; Yin, X.M. Sorting, recognition and activation of the misfolded protein degradation pathways through macroautophagy and the proteasome. Autophagy 2007, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi, P.; Chen, D.; Rogers, A.N.; Katewa, S.D.; Li, P.W.-L.; Thomas, E.L.; Kockel, L. With tor, less is more: A key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing tor pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: Autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell 2005, 120, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, B.; Klionsky, D.J. Development by self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev. Cell 2004, 6, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, T. Autophagy: A regulated bulk degradation process inside cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 313, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhao, L.; Kuang, M.; Zhang, B.; Liang, Z.; Yi, T.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, X. Autophagy in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy: Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? Cancer Lett. 2012, 323, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Klionsky, D.J. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Mammalian autophagy: Core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010, 22, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Klionsky, D.J. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kirisako, T.; Noda, T.; Kominami, E.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5720–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Yamamoto, A.; Hatano, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kabeya, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Tokuhisa, T.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotzer, V.L.; Blum, J.S. Autophagy and its role in mhc-mediated antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 3335–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannage, M.; Münz, C. Mhc presentation via autophagy and how viruses escape from it. Semin. Immunopathol. 2010, 32, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, S.-K.; Khanna, R. Autophagy mediates transporter associated with antigen processing-independent presentation of viral epitopes through MHC class I pathway. Blood 2012, 120, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Into, T.; Inomata, M.; Takayama, E.; Takigawa, T. Autophagy in regulation of toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvedahl, A.; Alexander, D.; Talloczy, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, W.; Burns, D.; Leib, D.A.; Levine, B. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, L.; Chemali, M.; Duron, J.; Rondeau, C.; Laplante, A.; Gingras, D.; Alexander, D.; Leib, D.; Norbury, C.; Lippe, R.; et al. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvedahl, A.; MacPherson, S.; Sumpter, R., Jr.; Tallóczy, Z.; Zou, Z.; Levine, B. Autophagy protects against sindbis virus infection of the central nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Kleeman, L.K.; Jiang, H.H.; Gordon, G.; Goldman, J.E.; Berry, G.; Herman, B.; Levine, B. Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by Beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8586–8596. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, S. VSV infection is sensed by Drosophila, attenuates nutrient signaling, and thereby activates antiviral autophagy. Autophagy 2009, 5, 1062–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattingre, S.; Tassa, A.; Qu, X.; Garuti, R.; Liang, X.H.; Mizushima, N.; Packer, M.; Schneider, M.D.; Levine, B. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 2005, 122, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, B.; Woo, J.S.; Liang, C.; Lee, K.H.; Hong, H.S.; E, X.; Kim, K.S.; Jung, J.U.; Oh, B.H. Structural and biochemical bases for the inhibition of autophagy and apoptosis by viral Bcl-2 of murine gamma-herpesvirus 68. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Li, Q.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, H.-R.; Chang, H.; Zhou, F.-C.; Gao, S.-J.; Liang, C.; et al. Flip-mediated autophagy regulation in cell death control. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, G.B.; Dinkins, C.; Davis, A.S.; Roberts, E.; Singh, S.B.; Dong, C.; Wu, L.; Kominami, E.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, A.; et al. Autophagy pathway intersects with Hiv-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannagé, M.; Dormann, D.; Albrecht, R.; Dengjel, J.; Torossi, T.; Rämer, P.C.; Lee, M.; Strowig, T.; Arrey, F.; Conenello, G.; et al. Matrix protein 2 of influenza a virus blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, H.; Yuan, Z. Subversion of cellular autophagy machinery by hepatitis B virus for viral envelopment. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6319–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Kirkegaard, K. Potential subversion of autophagosomal pathway by picornaviruses. Autophagy 2008, 4, 286–289. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, A.L.; Dykxhoorn, D.M.; Benita, Y.; Yan, N.; Engelman, A.; Xavier, R.J.; Lieberman, J.; Elledge, S.J. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science 2008, 319, 921–926. [Google Scholar]

- Dreux, M.; Gastaminza, P.; Wieland, S.F.; Chisari, F.V. The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14046–14051. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, J.E.; Wudzinska, A.; Datan, E.; Quaglino, D.; Zakeri, Z. Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 22147–22159. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, N.S.; Randall, G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-K.; Liang, J.-J.; Liao, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-L. Autophagy is involved in the early step of japanese encephalitis virus infection. Microbes Infect. 2012, 14, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, E.; Pierini, R.; Roberts, R.; Wileman, T. Origins of membrane vesicles generated during replication of positive-strand RNA viruses. Future Virol. 2009, 4, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, R., Jr.; Levine, B. Selective autophagy and viruses. Autophagy 2011, 7, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreux, M.; Chisari, F.V. Impact of the autophagy machinery on hepatitis C virus infection. Viruses 2011, 3, 1342–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.W.; Ducroux, A.; Jeang, K.T.; Neuveut, C. Impact of cellular autophagy on viruses: Insights from hepatitis B virus and human retroviruses. J. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wileman, T. Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication. Science 2006, 312, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvedahl, A.; Levine, B. Viral evasion of autophagy. Autophagy 2007, 4, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.P.; Jackson, W.T. Viruses and arrested autophagosome development. Autophagy 2009, 5, 870–871. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, E.; Jerome, W.G.; Yoshimori, T.; Mizushima, N.; Denison, M.R. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10136–10141. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, E.; McAuliffe, J.; Lu, X.; Subbarao, K.; Denison, M.R. Identification and characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replicase proteins. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9977–9986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Thackray, L.B.; Miller, B.C.; Lynn, T.M.; Becker, M.M.; Ward, E.; Mizushima, N.N.; Denison, M.R.; Virgin, H.W.T. Coronavirus replication does not require the autophagy gene ATG5. Autophagy 2007, 3, 581–585. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.; Ackermann, K.; Stuart, M.; Wex, C.; Protzer, U.; Schätzl, H.M.; Gilch, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication is severely impaired by MG132 due to proteasome-independent inhibition of M-calpain. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10112–10122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, C.A.; Reggiori, F. Are nidoviruses hijacking the autophagy machinery? Autophagy 2007, 4, 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Cottam, E.M.; Maier, H.J.; Manifava, M.; Vaux, L.C.; Chandra-Schoenfelder, P.; Gerner, W.; Britton, P.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Wileman, T. Coronavirus nsp6 proteins generate autophagosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum via an omegasome intermediate. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiori, F.; Monastyrska, I.; Verheije, M.H.; Calì, T.; Ulasli, M.; Bianchi, S.; Bernasconi, R.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Molinari, M. Coronaviruses Hijack the LC3-I-positive EDEMosomes, ER-derived vesicles exporting short-lived ERAD regulators, for replication. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, R.; Galli, C.; Noack, J.; Bianchi, S.; de Haan, Cornelis A.M.; Reggiori, F.; Molinari, M. Role of the SEL1L:LC3-I complex as an ERAD tuning receptor in the mammalian ER. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, R.; Noack, J.; Molinari, M. Unconventional roles of nonlipidated LC3 in ERAD tuning and coronavirus infection. Autophagy 2012, 8, 1534–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi, R.; Molinari, M. ERAD and ERAD tuning: Disposal of cargo and of ERAD regulators from the mammalian ER. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011, 23, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calì, T.; Galli, C.; Olivari, S.; Molinari, M. Segregation and rapid turnover of EDEM1 by an autophagy-like mechanism modulates standard ERAD and folding activities. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).