Combined Glycoprotein Mutations in Rabies Virus Promote Astrocyte Tropism and Protective CNS Immunity in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cell Lines

2.2. Primary Astrocyte Culture

2.3. One-Step and Multi-Step Growth Curves

2.4. Infection of Cells for Immunocytochemistry

2.5. Intracerebral Infection of Mice

2.6. Intranasal Infection of Mice

2.7. Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence Analyses

2.8. Virus Isolation from the Brains of Infected Mice

2.9. RNA Isolation and Quantitative PCR

2.10. Statistical Analysis

2.11. Software

3. Results

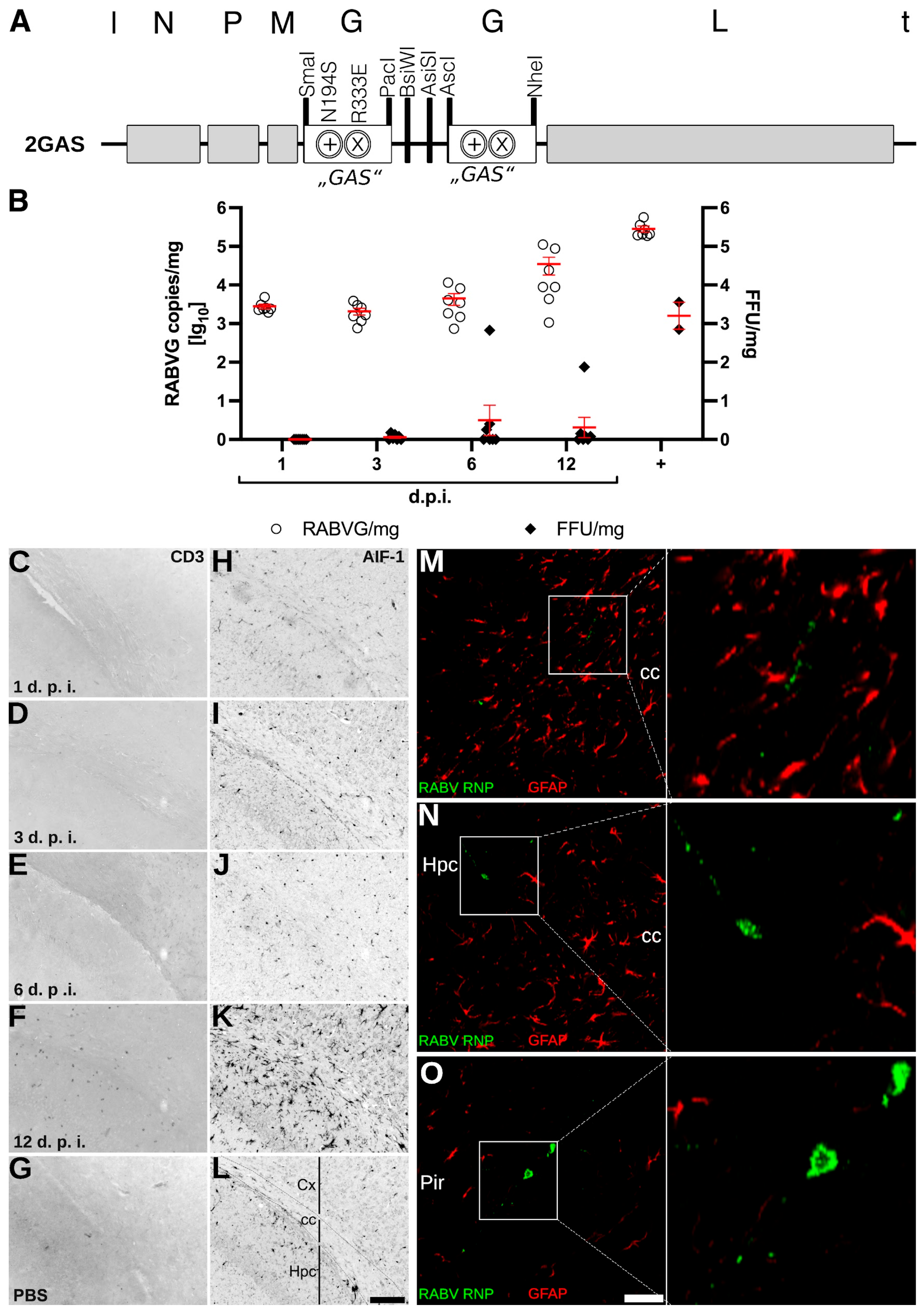

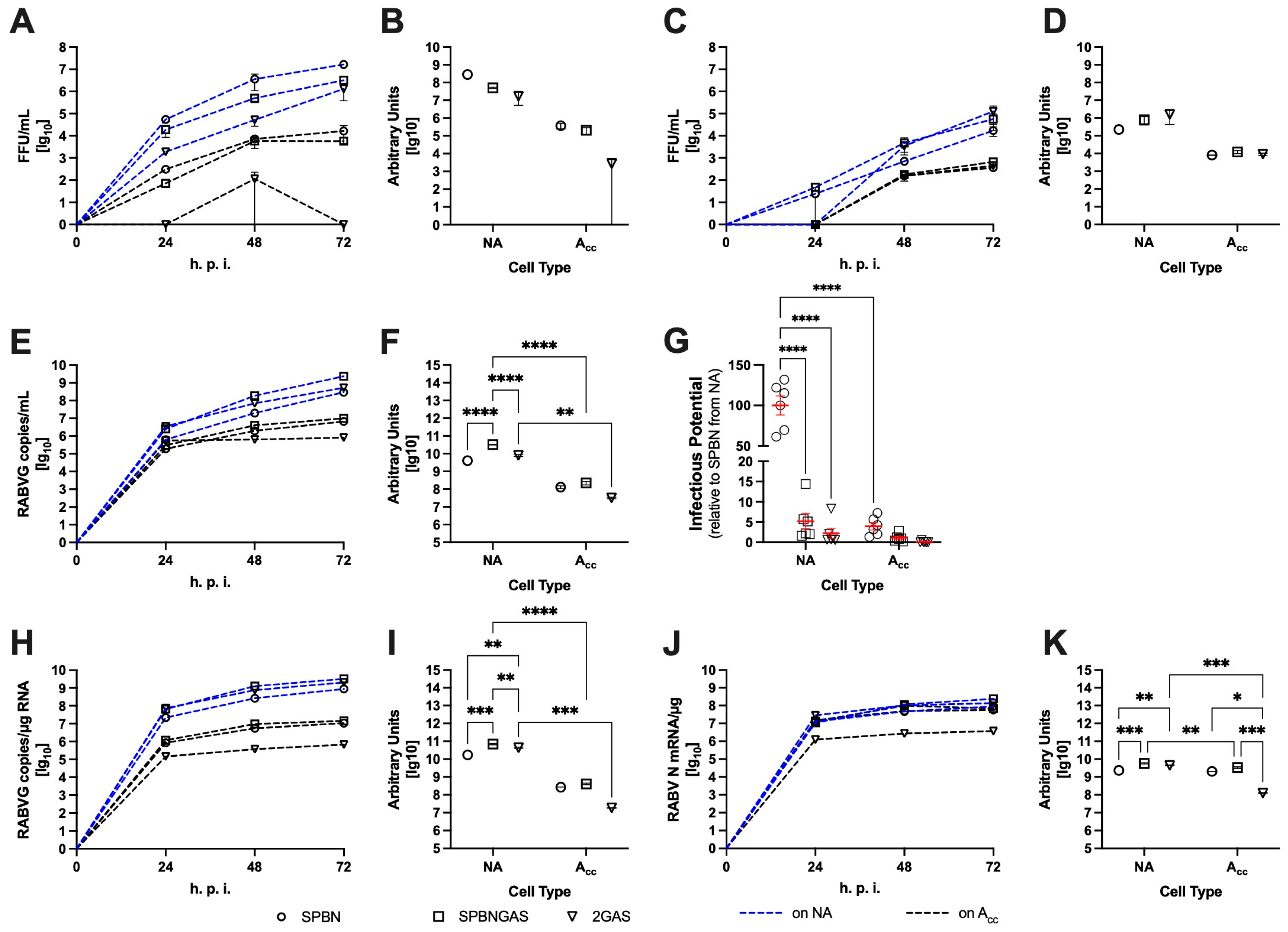

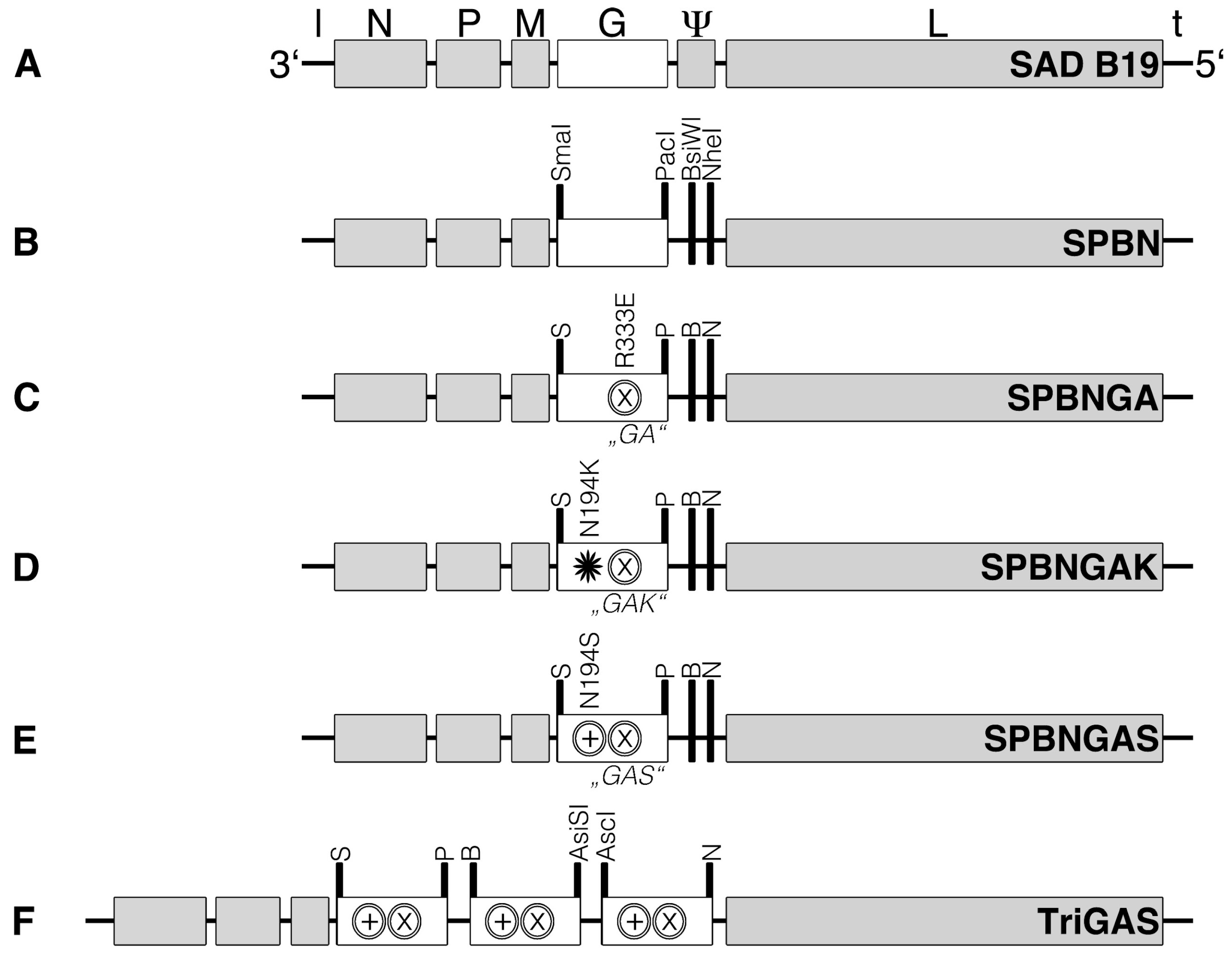

3.1. Amino Acid Substitutions at Position 194 of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Are Associated with Altered Virus Distribution in Mouse Brains After Intracerebral Injection

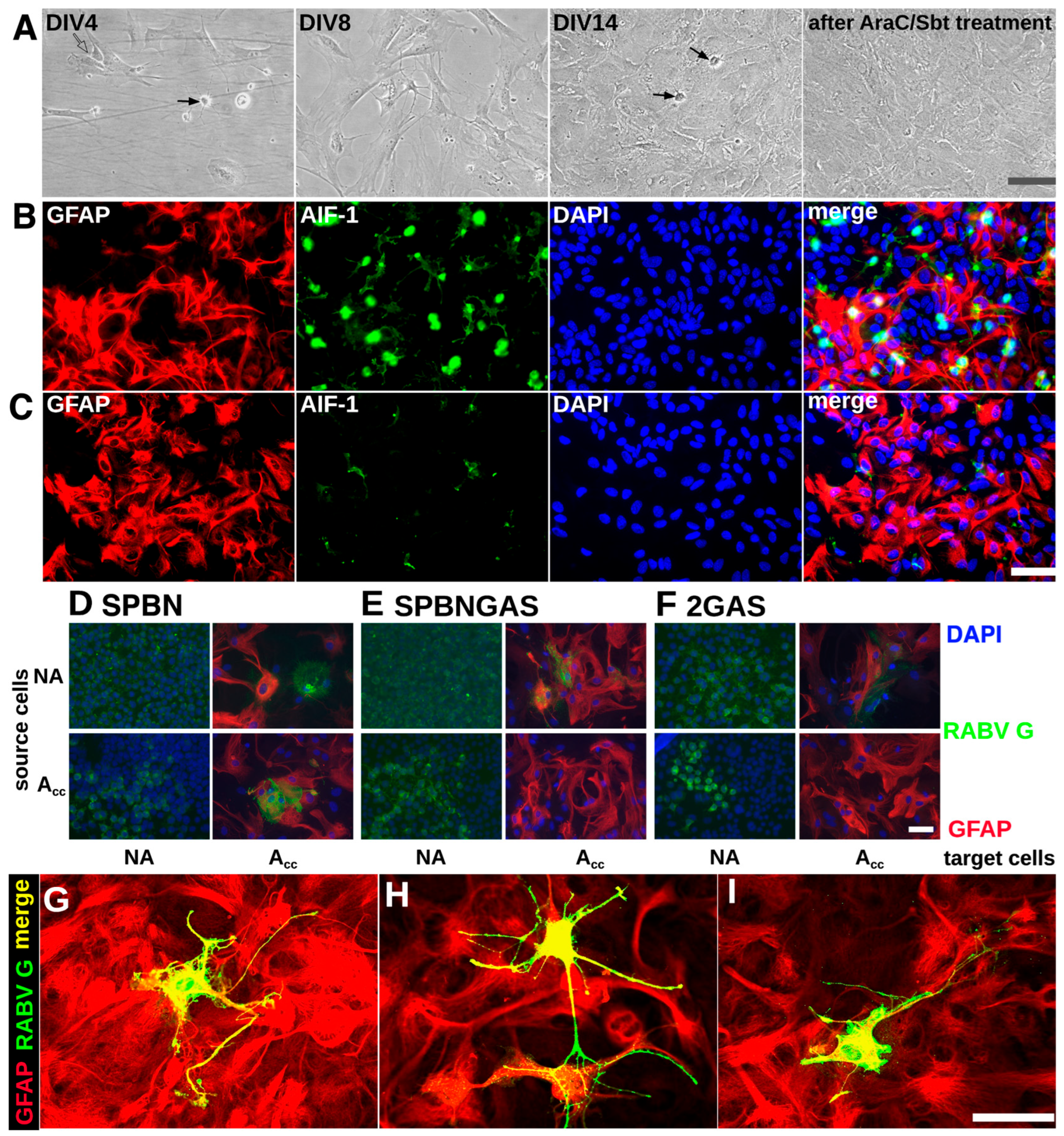

3.2. Amino Acid Substitutions at Position 194 of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Are Associated with Altered Cellular Tropism Patterns

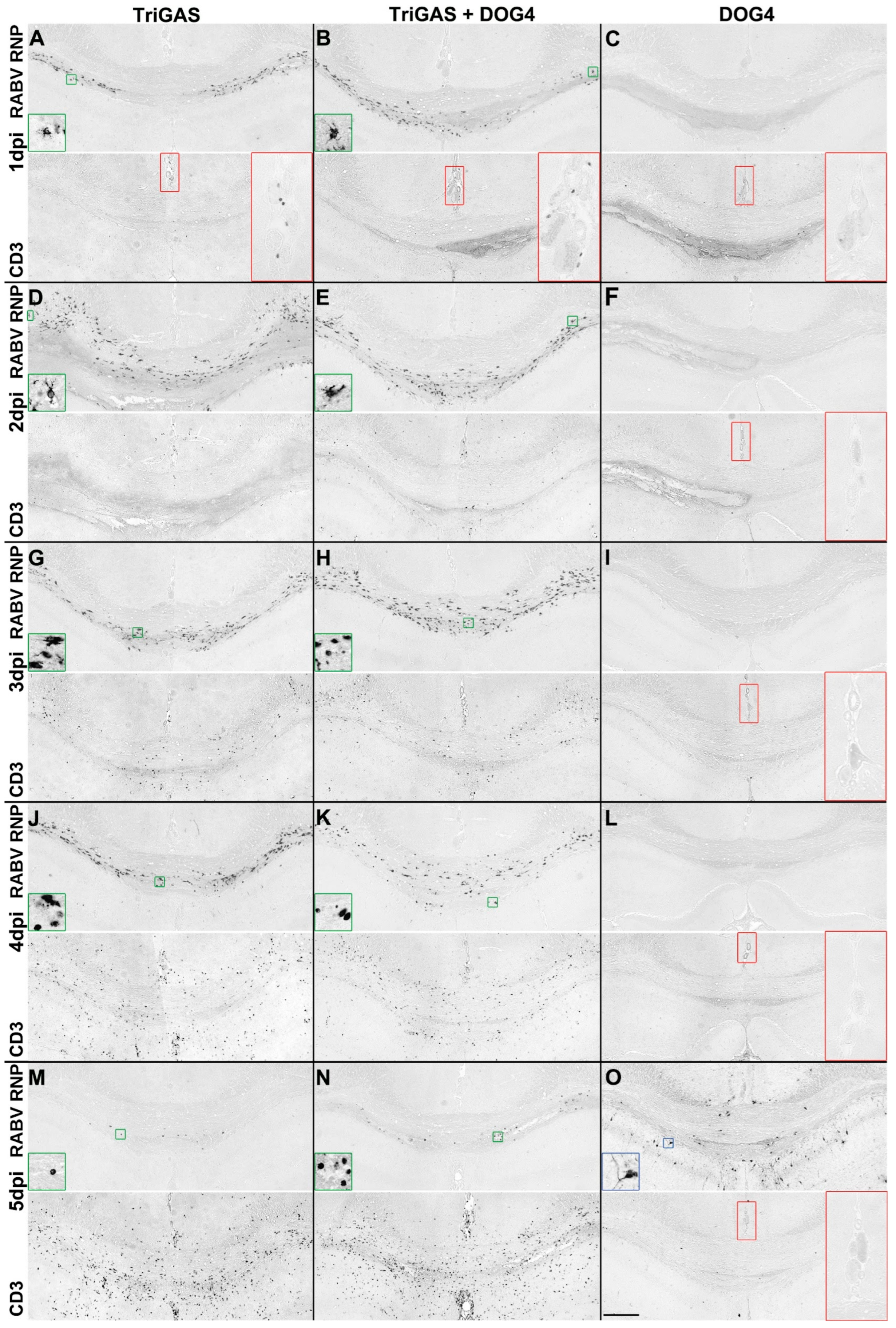

3.3. Immune Responses to RABV Infection Differ Based on the Amino Acids at Positions 333 and 194 of the Glycoprotein

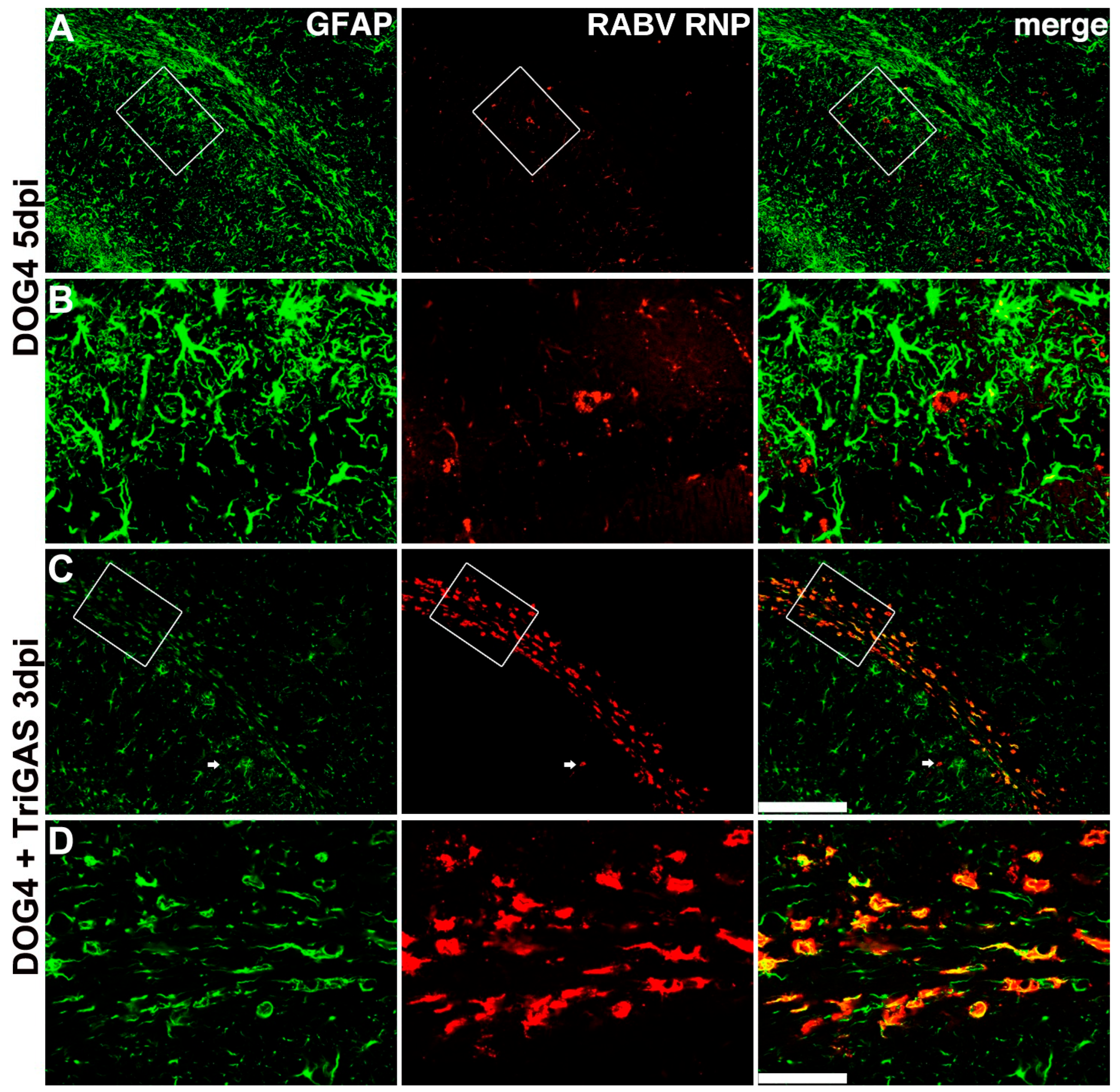

3.4. Astrocyte Activation Depends on the Amino Acid at Position 194 of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein

3.5. Astrocytotropic Rabies Virus Variant TriGAS Defines Infection and Immune Response Patterns During Mixed Intracerebral Infection

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2GAS | Recombinant SPBN-based RABV variant carrying two copies of the GAS glycoprotein gene |

| Acc | Primary astrocytes from the murine corpus callosum |

| AIF-1 | Allograft inflammatory factor 1 |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AraC | Cytosine arabinoside |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BSR | Baby hamster kidney (BSR) cell line expressing T7 polymerase |

| C1q | Complement component 1q |

| CCL4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 |

| CD3 | Cluster of differentiation 3 (T-cell marker) |

| cc | Corpus callosum |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| Ct | Threshold cycle |

| Cx | Neocortex |

| DAMPs | Danger-associated molecular patterns |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DIV | Days in vitro |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNase I | Deoxyribonuclease I |

| DOG4 | Highly pathogenic dog-originated rabies virus strain DOG4 |

| DRV4 | Dog rabies virus isolate 4 (original designation of DOG4) |

| d.p.i. | Days post infection |

| FAD | Fluorescent antibody dilution buffer |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FFU | Focus-forming unit |

| G | Glycoprotein |

| GAS | RABV G gene carrying the R333E pathogenicity determinant and N194S substitution |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| Hpc | Hippocampus |

| h.p.i. | Hours post infection |

| IC-LD50 | 50% intracerebral lethal dose |

| IFN(-β, -γ) | Interferon (beta, gamma) |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| i.c. | Intracerebral |

| i.n. | Intranasal |

| L | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (large protein) |

| LOEWE | Initiative for Excellence in Science and Technology of the state of Hessen |

| M | Matrix protein |

| m.o.i. | Multiplicity of infection |

| mGluR2 | Metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 |

| NA | Neuroblastoma cell line of A/J mouse origin |

| nAChR | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

| NCAM | Neural cell adhesion molecule |

| N | Nucleoprotein |

| P | Phosphoprotein |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PEP | Postexposure prophylaxis |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RABV | Rabies virus |

| RABVG | Rabies virus genome |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium |

| RT | Reverse transcription |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SAD B19 | Street Alabama Dufferin B19 rabies virus strain |

| Sbt | Sorbitol |

| SELP | P-selectin (endothelial activation molecule) |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SFM | Serum-free medium (OptiPro SFM) |

| SPBN | Recombinant derivative of SAD B19 with pseudogene deleted and modified G locus |

| SPBNGA | SPBN variant carrying R333E mutation in G (“GA”) |

| SPBNGAK | SPBN variant carrying N194K and R333E mutations in G (“GAK”) |

| SPBNGAS | SPBN variant carrying N194S and R333E mutations in G (“GAS”) |

| SVZ | Subventricular zone |

| VNAs | Virus-neutralizing antibodies |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Name | Nucleotide Sequence (5′-3′) | Target, Sense |

|---|---|---|

| MP079 | ACACCCCTACAATGGATGC | RABV genome, forward |

| MP080 | GGGTTATACAGGGCTTTTTCA | RABV genome, reverse |

| MP081 | ACAGGAGGCATGGAACTGAC | RABV N mRNA, forward |

| MP082 | TGTTTTGCCCGGATATTTTG | RABV N mRNA, reverse |

| Parameter | RABVG (MP079/MP080) | RABV N mRNA (MP081/MP082) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard line equation | ||

| PCR efficiency | 100% | 100% |

| R2 | 0.99981 | 0.99953 |

| Limit of quantification | 32.12 Ct | 29.36 Ct |

| Limit of detection | 102 amplicons | 102 amplicons |

| Linear range | 102–107 amplicons | 102–107 amplicons |

References

- Hemachudha, T.; Sunsaneewitayakul, B.; Mitrabhakdi, E.; Suankratay, C.; Laothamathas, J.; Wacharapluesadee, S.; Khawplod, P.; Wilde, H. Paralytic Complications Following Intravenous Rabies Immune Globulin Treatment in a Patient with Furious Rabies. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 7, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiler, F.A.; Jackson, A.C. Critical Appraisal of the Milwaukee Protocol for Rabies: This Failed Approach Should Be Abandoned. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 43, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.C. Demise of the Milwaukee Protocol for Rabies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 81, e229–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, K.; Coudeville, L.; Lembo, T.; Sambo, M.; Kieffer, A.; Attlan, M.; Barrat, J.; Blanton, J.D.; Briggs, D.J.; Cleaveland, S.; et al. Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; Streicker, D.G.; Schnell, M.J. The Spread and Evolution of Rabies Virus: Conquering New Frontiers. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, A.A.V.; Wernimont, A.K.; Muziol, T.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Clapier, C.R.; Schoehn, G.; Weissenhorn, W.; Ruigrok, R.W.H. Crystal Structure of the Rabies Virus Nucleoprotein-RNA Complex. Science 2006, 313, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.S.; Preuss, M.A.R.; Williams, J.C.; Schnell, M.J. The Dynein Light Chain 8 Binding Motif of Rabies Virus Phosphoprotein Promotes Efficient Viral Transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7229–7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzózka, K.; Finke, S.; Conzelmann, K.-K. Identification of the Rabies Virus Alpha/Beta Interferon Antagonist: Phosphoprotein P Interferes with Phosphorylation of Interferon Regulatory Factor 3. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7673–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebatsion, T.; Weiland, F.; Conzelmann, K.K. Matrix Protein of Rabies Virus Is Responsible for the Assembly and Budding of Bullet-Shaped Particles and Interacts with the Transmembrane Spike Glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudin, Y.; Ruigrok, R.W.H.; Tuffereau, C.; Knossow, M.; Flamand, A. Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Is a Trimer. Virology 1992, 187, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, K.; Foley, H.D.; McGettigan, J.P.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. Reinvestigation of the Role of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein in Viral Pathogenesis Using a Reverse Genetics Approach. J. Neurovirol. 2000, 6, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Pulmanausahakul, R.; Hodawadekar, S.S.; Spitsin, S.; McGettigan, J.P.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. Overexpression of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Results in Enhancement of Apoptosis and Antiviral Immune Response. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3374–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaldi, P.E.; Fayet, J.; Conzelmann, K.K.; Tsiang, H. Infection Characteristics of Rabies Virus Variants with Deletion or Insertion in the Pseudogene Sequence. J. Neurovirol. 1998, 4, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Pulmanausahakul, R.; Nagao, K.; Prosniak, M.; Rice, A.B.; Koprowski, H.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. Identification of Viral Genomic Elements Responsible for Rabies Virus Neuroinvasiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16328–16332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, L.; Zaeck, L.M.; Sehl-Ewert, J.; Finke, S.; Bourhy, H. Innate Immune Signaling and Role of Glial Cells in Herpes Simplex Virus- and Rabies Virus-Induced Encephalitis. Viruses 2021, 13, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, G.; Mohamed, M.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Bartee, E. Cytokine Determinants of Viral Tropism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, T.L.; Burrage, T.G.; Smith, A.L.; Crick, J.; Tignor, G.H. Is the Acetylcholine Receptor a Rabies Virus Receptor. Science 1982, 215, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffereau, C.; Bénéjean, J.; Blondel, D.; Kieffer, B.; Flamand, A. Low-Affinity Nerve-Growth Factor Receptor (P75NTR) Can Serve as a Receptor for Rabies Virus. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 7250–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoulouze, M.; Lafage, M.; Schachner, M.; Hartmann, U.; Cremer, H.; Lafon, M. The Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule Is a Receptor for Rabies Virus. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7181–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Shuai, L.; Wang, X.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Ge, J.; et al. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Subtype 2 Is a Cellular Receptor for Rabies Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferkorn, C.; Kallfass, C.; Lienenklaus, S.; Spanier, J.; Kalinke, U.; Rieder, M.; Conzelmann, K.-K.; Michiels, T.; Staeheli, P. Abortively Infected Astrocytes Appear to Represent the Main Source of Interferon Beta in the Virus-Infected Brain. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.C.; Phelan, C.C.; Rossiter, J.P. Infection of Bergmann Glia in the Cerebellum of a Skunk Experimentally Infected with Street Rabies Virus. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2000, 64, 226–228. [Google Scholar]

- Potratz, M.; Zaeck, L.; Christen, M.; Te Kamp, V.; Klein, A.; Nolden, T.; Freuling, C.; Müller, T.; Finke, S. Astrocyte Infection during Rabies Encephalitis Depends on the Virus Strain and Infection Route as Demonstrated by Novel Quantitative 3D Analysis of Cell Tropism. Cells 2020, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Baolige, D.; Zhao, S.; Hu, W.; Yang, Y. Change in the Single Amino Acid Site 83 in Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Enhances the BBB Permeability and Reduces Viral Pathogenicity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 632957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, B.; Lyu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. Single Amino Acid Change at Position 255 in Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Decreases Viral Pathogenicity. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9650–9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulon, P.; Ternaux, J.P.; Flamand, A.; Tuffereau, C. An Avirulent Mutant of Rabies Virus Is Unable to Infect Motoneurons in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, Y.; Tabata, K.; Morimoto, K.; Ito, N.; Chambaro, H.M.; Eguchi, R.; Otsuguro, K.; Hall, W.W.; Orba, Y.; Sawa, H.; et al. Glu333 in Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Is Involved in Virus Attenuation through Astrocyte Infection and Interferon Responses. iScience 2022, 25, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X. Amino Acid Mutation in Position 349 of Glycoprotein Affect the Pathogenicity of Rabies Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama-Ito, M.; Ito, N.; Yamada, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Minamoto, N. Multiple Amino Acids in the Glycoprotein of Rabies Virus Are Responsible for Pathogenicity in Adult Mice. Virus Res. 2006, 115, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seif, I.; Coulon, P.; Rollin, P.E.; Flamand, A. Rabies Virulence: Effect on Pathogenicity and Sequence Characterization of Rabies Virus Mutations Affecting Antigenic Site III of the Glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1985, 53, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, K.; McGettigan, J.P.; Foley, H.D.; Hooper, D.C.; Dietzschold, B.; Schnell, M.J. Genetic Engineering of Live Rabies Vaccines. Vaccine 2001, 19, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Ge, J.; Wang, X.; Zhai, H.; Hua, T.; Zhao, B.; Kong, D.; Yang, C.; Chen, H.; Bu, Z. Molecular Basis of Neurovirulence of Flury Rabies Virus Vaccine Strains: Importance of the Polymerase and the Glycoprotein R333Q Mutation. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 8926–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Ito, N.; Masatani, T.; Abe, M.; Yamaoka, S.; Ito, Y.; Okadera, K.; Sugiyama, M. Generation of a Live Rabies Vaccine Strain Attenuated by Multiple Mutations and Evaluation of Its Safety and Efficacy. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3610–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Feng, N.; Wang, X.; Ge, J.; Wen, Z.; Chen, W.; Qin, L.; Xia, X.; Bu, Z. Genetically Modified Rabies Virus ERA Strain Is Safe and Induces Long-Lasting Protective Immune Response in Dogs after Oral Vaccination. Antiviral Res. 2015, 121, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Okamoto, T.; Sasaki, M.; Miyamoto, S.; Takahashi, T.; Izumi, F.; Inukai, M.; Jarusombuti, S.; Okada, K.; Nakagawa, K.; et al. Safety Enhancement of a Genetically Modified Live Rabies Vaccine Strain by Introducing an Attenuating Leu Residue at Position 333 in the Glycoprotein. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3777–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, T.L.; Wilson, P.T.; Hawrot, E.; Speicher, D.W. Amino Acid Sequence Similarity between Rabies Virus Glycoprotein and Snake Venom Curaremimetic Neurotoxins. Science 1984, 226, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Faber, M.-L.; Papaneri, A.; Bette, M.; Weihe, E.; Dietzschold, B.; Schnell, M.J. A Single Amino Acid Change in Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Increases Virus Spread and Enhances Virus Pathogenicity. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14141–14148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselheiro, J.A.; Barone, G.T.; Miyagi, S.A.T.; de Souza Silva, S.O.; Agostinho, W.C.; Aguiar, J.; Brandão, P.E. Evolution of Rabies Virus Isolates: Virulence Signatures and Effects of Modulation by Neutralizing Antibodies. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Ito, N.; Saito, S.; Masatani, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Atoji, Y.; Sugiyama, M. Amino Acid Substitutions at Positions 242, 255 and 268 in Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Affect Spread of Viral Infection. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010, 54, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.C.; Morimoto, K.; Bette, M.; Weihe, E.; Koprowski, H.; Dietzschold, B. Collaboration of Antibody and Inflammation in Clearance of Rabies Virus from the Central Nervous System. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3711–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Hooper, D.C. Lethal Silver-Haired Bat Rabies Virus Infection Can Be Prevented by Opening the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 7993–7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, M.; Chai, Q.; Wu, H.; Fu, Z.F. Enhancement of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Is Required for Intravenously Administered Virus Neutralizing Antibodies to Clear an Established Rabies Virus Infection from the Brain and Prevent the Development of Rabies in Mice. Antiviral Res. 2014, 110, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, F.; Miyamoto, S.; Masatani, T.; Sasaki, M.; Kawakami, K.; Takahashi, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Fujii, Y.; Okajima, M.; Nishiyama, S.; et al. Generation and Characterization of a Genetically Modified Live Rabies Vaccine Strain with Attenuating Mutations in Multiple Viral Proteins and Evaluation of Its Potency in Dogs. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4907–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.S.-K.; Wong, C.H.-L.; Choi, H.C.-W. Cost-Effectiveness of Intranasal Live-Attenuated Influenza Vaccine for Children: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Faber, M.-L.; Li, J.; Preuss, M.A.R.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. Dominance of a Nonpathogenic Glycoprotein Gene over a Pathogenic Glycoprotein Gene in Rabies Virus. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 7041–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa-Muto, J.; Ito, N.; Yamada, K.; Shimizu, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Minamoto, N. Characterization of Recombinant Rabies Virus Carrying Double Glycoprotein Genes. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006, 50, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, J.; Ai, J.; Dun, C.; Fu, Z.F.; Niu, X.; Guo, X. A Recombinant Rabies Virus Encoding Two Copies of the Glycoprotein Gene Confers Protection in Dogs against a Virulent Challenge. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, M.J.; Mebatsion, T.; Conzelmann, K.K. Infectious Rabies Viruses from Cloned cDNA. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 4195–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutsky, K.; Curtis, D.; Bongiorno, E.K.; Barkhouse, D.A.; Kean, R.B.; Dietzschold, B.; Hooper, D.C.; Faber, M. Intramuscular Inoculation of Mice with the Live-Attenuated Recombinant Rabies Virus TriGAS Results in a Transient Infection of the Draining Lymph Nodes and a Robust, Long-Lasting Protective Immune Response against Rabies. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Li, J.; Kean, R.B.; Hooper, D.C.; Alugupalli, K.R.; Dietzschold, B. Effective Preexposure and Postexposure Prophylaxis of Rabies with a Highly Attenuated Recombinant Rabies Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11300–11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzelmann, K.-K.; Cox, J.H.; Schneider, L.G.; Thiel, H.J. Molecular Cloning and Complete Nucleotide Sequence of the Attenuated Rabies Virus SAD B19. Virology 1990, 175, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietzschold, M.-L.; Faber, M.; Mattis, J.A.; Pak, K.Y.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. In Vitro Growth and Stability of Recombinant Rabies Viruses Designed for Vaccination of Wildlife. Vaccine 2004, 23, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, U.J.; Finke, S.; Conzelmann, K.-K. Generation of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 Is Not Essential for Virus Replication in Tissue Culture, and the Human RSV Leader Region Acts as a Functional BRSV Genome Promoter. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzelmann, K.-K.; Schnell, M.J. Rescue of Synthetic Genomic RNA Analogs of Rabies Virus by Plasmid-Encoded Proteins. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Maeda, N.; Yoshida, H.; Urade, M.; Saito, S. Plaque Formation of Herpes Virus Hominis Type 2 and Rubella Virus in Variants Isolated from the Colonies of BHK21/WI-2 Cells Formed in Soft Agar. Arch. Virol. 1977, 53, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzschold, B.; Morimoto, K.; Hooper, D.C.; Smith, J.S.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Koprowski, H. Genotypic and Phenotypic Diversity of Rabies Virus Variants Involved in Human Rabies: Implications for Postexposure Prophylaxis. J. Hum. Virol. 2000, 3, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ertel, A.; Portocarrero, C.; Barkhouse, D.; Dietzschold, B.; Hooper, D.; Faber, M. Postexposure Treatment with the Live-Attenuated Rabies Virus (RV) Vaccine TriGAS Triggers the Clearance of Wild-Type RV from the Central Nervous System (CNS) through the Rapid Induction of Genes Relevant to Adaptive Immunity in CNS Tissues. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3200–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, C.; Matyash, M.; Pivneva, T.; Schipke, C.G.; Ohlemeyer, C.; Hanisch, U.-K.; Kirchhoff, F.; Kettenmann, H. GFAP Promoter-Controlled EGFP-Expressing Transgenic Mice: A Tool to Visualize Astrocytes and Astrogliosis in Living Brain Tissue. Glia 2001, 33, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.D.; de Vellis, J. Preparation of Separate Astroglial and Oligodendroglial Cell Cultures from Rat Cerebral Tissue. J. Cell Biol. 1980, 85, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulian, D.; Baker, T.J. Characterization of Ameboid Microglia Isolated from Developing Mammalian Brain. J. Neurosci. 1986, 6, 2163–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.; Angulo, E.; Ejarque, A.; Casadó, V.; Tusell, J.M.; Moratalla, R.; Chen, J.-F.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Lluis, C.; Franco, R.; et al. Adenosine A2A Receptor Stimulation Potentiates Nitric Oxide Release by Activated Microglia. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, H.; Thiess, U.; Hamprecht, B. Sorbitol Pathway Activity and Utilization of Polyols in Astroglia-Rich Primary Cultures. Glia 1990, 3, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, H.; Schuricht, B.; Hamprecht, B. Replacement of Glucose by Sorbitol in Growth Medium Causes Selection of Astroglial Cells from Heterogeneous Primary Cultures Derived from Newborn Mouse Brain. Brain Res. 1991, 550, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamby, M.E.; Uliasz, T.F.; Hewett, S.J.; Hewett, J.A. Characterization of an Improved Procedure for the Removal of Microglia from Confluent Monolayers of Primary Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Methods 2006, 150, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charan, J.; Kantharia, N.D. How to Calculate Sample Size in Animal Studies? J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman-Culleré, M.H.; Foltz, C.J. Body Condition Scoring: A Rapid and Accurate Method for Assessing Health Status in Mice. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1999, 49, 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, M.; Bette, M.; Preuss, M.A.R.; Pulmanausahakul, R.; Rehnelt, J.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B.; Weihe, E. Overexpression of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha by a Recombinant Rabies Virus Attenuates Replication in Neurons and Prevents Lethal Infection in Mice. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15405–15416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulmanausahakul, R.; Faber, M.; Morimoto, K.; Spitsin, S.; Weihe, E.; Hooper, D.C.; Schnell, M.J.; Dietzschold, B. Overexpression of Cytochrome C by a Recombinant Rabies Virus Attenuates Pathogenicity and Enhances Antiviral Immunity. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 10800–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoune, M.A.R.; Nickl, B.; Krieger, T.; Wohlers, L.; Bonaterra, G.A.; Dietzschold, B.; Weihe, E.; Bette, M. The Phenotype of the RABV Glycoprotein Determines Cellular and Global Virus Load in the Brain and Is Decisive for the Pace of the Disease. Virology 2017, 511, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaeble, W.; Schäfer, M.K.; Petry, F.; Fink, T.; Knebel, D.; Weihe, E.; Loos, M. Follicular Dendritic Cells, Interdigitating Cells, and Cells of the Monocyte-Macrophage Lineage Are the C1q-Producing Sources in the Spleen. Identification of Specific Cell Types by in Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemical Analysis. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 4971–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; DeZonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next Generation of Scientific Image Data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potratz, M.; Zaeck, L.M.; Weigel, C.; Klein, A.; Freuling, C.M.; Müller, T.; Finke, S. Neuroglia Infection by Rabies Virus after Anterograde Virus Spread in Peripheral Neurons. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zhou, M.; Yang, Y.; Yu, L.; Luo, Z.; Tian, D.; Wang, K.; Cui, M.; Chen, H.; Fu, Z.F.; et al. Lab-Attenuated Rabies Virus Causes Abortive Infection and Induces Cytokine Expression in Astrocytes by Activating Mitochondrial Antiviral-Signaling Protein Signaling Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.; Eggerbauer, E.; Potratz, M.; Zaeck, L.; Calvelage, S.; Finke, S.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C. Comparative Pathogenesis of Different Phylogroup I Bat Lyssaviruses in a Standardized Mouse Model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0009845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, G. Specificity of Rabies Virus as a Transneuronal Tracer of Motor Networks: Transfer from Hypoglossal Motoneurons to Connected Second-Order and Higher Order Central Nervous System Cell Groups. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995, 356, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.M.; Strick, P.L. Rabies as a Transneuronal Tracer of Circuits in the Central Nervous System. J. Neurosci. Methods 2000, 103, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietzschold, B.; Wiktor, T.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Macfarlan, R.I.; Wunner, W.H.; Torres-Anjel, M.J.; Koprowski, H. Differences in Cell-to-Cell Spread of Pathogenic and Apathogenic Rabies Virus in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Virol. 1985, 56, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.M.; Fedosyuk, S.; English, S.; Augusto, G.; Berg, A.; Thorley, L.; Haselon, A.-S.; Segireddy, R.R.; Bowden, T.A.; Douglas, A.D. Structure of Trimeric Pre-Fusion Rabies Virus Glycoprotein in Complex with Two Protective Antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1219–1230.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, L.; Young, K.; Cerapio, J.P.; Kozaki, T.; Kergoat, L.; Libri, V.; Ginhoux, F.; Hasan, M.; Ameur, L.B.; Chin, G.; et al. Human Brain Cell Types Shape Host-Rabies Virus Transcriptional Interactions Revealing a Preexisting pro-Viral Astrocyte Subpopulation. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.B.; Power, C.; Lynch, W.P.; Ewalt, L.C.; Lodmell, D.L. Rabies Viruses Infect Primary Cultures of Murine, Feline, and Human Microglia and Astrocytes. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosniak, M.; Zborek, A.; Scott, G.S.; Roy, A.; Phares, T.W.; Koprowski, H.; Hooper, D.C. Differential Expression of Growth Factors at the Cellular Level in Virus-Infected Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6765–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feige, L.; Kozaki, T.; Dias De Melo, G.; Guillemot, V.; Larrous, F.; Ginhoux, F.; Bourhy, H. Susceptibilities of CNS Cells towards Rabies Virus Infection Is Linked to Cellular Innate Immune Responses. Viruses 2022, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Préhaud, C.; Coulon, P.; Lafay, F.; Thiers, C.; Flamand, A. Antigenic Site II of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein: Structure and Role in Viral Virulence. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Mahmood, F.; Fu, Z.F. Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Is an Important Determinant for the Induction of Innate Immune Responses and the Pathogenic Mechanisms. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 162, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmansour, A.; Leblois, H.; Coulon, P.; Tuffereau, C.; Gaudin, Y.; Flamand, A.; Lafay, F. Antigenicity of Rabies Virus Glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 4198–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, L.C.; Pinheiro, A.P.D.S.; Gibaldi, D.; Silva, A.A.; e Silva, P.M.R.; Roffê, E.; Santiago, H.d.C.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Mineo, J.R.; Silva, N.M.; et al. Behavioral Alterations in Long-Term Toxoplasma Gondii Infection of C57BL/6 Mice Are Associated with Neuroinflammation and Disruption of the Blood Brain Barrier. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, F.; Bi, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, F.; Liang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Ju, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Transcriptional Profiling Reveals Two Distinct Outcomes in Central Nervous System Infections of Rabies Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomme, E.A.; Wirblich, C.; Addya, S.; Rall, G.F.; Schnell, M.J. Immune Clearance of Attenuated Rabies Virus Results in Neuronal Survival with Altered Gene Expression. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobe, K.; Ortmann, S.; Kaiser, C.; Perez-Bravo, D.; Gethmann, J.; Kliemt, J.; Körner, S.; Theuß, T.; Lindner, T.; Freuling, C.; et al. Efficacy of Oral Rabies Vaccine Baits Containing SPBN GASGAS in Domestic Dogs According to International Standards. Vaccines 2023, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhouse, D.A.; Faber, M.; Hooper, D.C. Pre- and Post-Exposure Safety and Efficacy of Attenuated Rabies Virus Vaccines Are Enhanced by Their Expression of IFNγ. Virology 2015, 474, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanadurai, C.W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Leyson, C.M.; Cooper, T.L.; Platt, S.R.; Harvey, S.B.; Hooper, D.C.; Faber, M.; et al. Differential Host Immune Responses after Infection with Wild-Type or Lab-Attenuated Rabies Viruses in Dogs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freuling, C.; Eggerbauer, E.; Finke, S.; Kaiser, C.; Kaiser, C.; Kretzschmar, A.; Nolden, T.; Ortmann, S.; Schröder, C.; Teifke, J.; et al. Efficacy of the Oral Rabies Virus Vaccine Strain SPBN GASGAS in Foxes and Raccoon Dogs. Vaccine 2019, 37, 4750–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuling, C.; Kamp, V.; Klein, A.; Günther, M.; Zaeck, L.; Potratz, M.; Eggerbauer, E.; Bobe, K.; Kaiser, C.; Kretzschmar, A.; et al. Long-Term Immunogenicity and Efficacy of the Oral Rabies Virus Vaccine Strain SPBN GASGAS in Foxes. Viruses 2019, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisén, J.; Johansson, C.B.; Török, C.; Risling, M.; Lendahl, U. Rapid, Widespread, and Longlasting Induction of Nestin Contributes to the Generation of Glial Scar Tissue after CNS Injury. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 131, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.C.S.; Matesic, D.F.; Marvin, M.; McKay, R.D.G.; Brüstle, O. Re-Expression of the Intermediate Filament Nestin in Reactive Astrocytes. Neurobiol. Dis. 1995, 2, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, N.; Schmidt-Kastner, R.; Hakim, A.M. Nestin Expression in Reactive Astrocytes Following Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Brain Res. 1997, 768, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffo, A.; Rite, I.; Tripathi, P.; Lepier, A.; Colak, D.; Horn, A.-P.; Mori, T.; Götz, M. Origin and Progeny of Reactive Gliosis: A Source of Multipotent Cells in the Injured Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3581–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumenyuk, A.V.; Tykhomyrov, A.A.; Savosko, S.I.; Guzyk, M.M.; Rybalko, S.L.; Ryzha, A.O.; Chaikovsky, Y.B. State of Astrocytes in the Mice Brain under Conditions of Herpes Viral Infection and Modeled Stroke. Neurophysiology 2018, 50, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallfass, C.; Ackerman, A.; Lienenklaus, S.; Weiss, S.; Heimrich, B.; Staeheli, P. Visualizing Production of Beta Interferon by Astrocytes and Microglia in Brain of La Crosse Virus-Infected Mice. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11223–11230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detje, C.N.; Lienenklaus, S.; Chhatbar, C.; Spanier, J.; Prajeeth, C.K.; Soldner, C.; Tovey, M.G.; Schlüter, D.; Weiss, S.; Stangel, M.; et al. Upon Intranasal Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Infection, Astrocytes in the Olfactory Bulb Are Important Interferon Beta Producers That Protect from Lethal Encephalitis. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Toriumi, H.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, H.; Fu, Z.F. The Roles of Chemokines in Rabies Virus Infection: Overexpression May Not Always Be Beneficial. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 11808–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galelli, A.; Baloul, L.; Lafon, M. Abortive Rabies Virus Central Nervous Infection Is Controlled by T Lymphocyte Local Recruitment and Induction of Apoptosis. J. Neurovirol. 2000, 6, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, O.S.; Song, G.S.; Kumar, M.; Yanagihara, R.; Lee, H.-W.; Song, J.-W. Hantaviruses Induce Antiviral and Pro-Inflammatory Innate Immune Responses in Astrocytic Cells and the Brain. Viral Immunol. 2014, 27, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, M.; Bergmann, C.C. Alpha/Beta Interferon (IFN-α/β) Signaling in Astrocytes Mediates Protection against Viral Encephalomyelitis and Regulates IFN-γ-Dependent Responses. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01901-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, A.; Freuling, C.; Ortmann, S.; Kretzschmar, A.; Mayer, D.; Schliephake, A.; Müller, T. An Assessment of Shedding with the Oral Rabies Virus Vaccine Strain SPBN GASGAS in Target and Non-Target Species. Vaccine 2018, 36, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortmann, S.; Kretzschmar, A.; Kaiser, C.; Lindner, T.; Freuling, C.; Kaiser, C.; Schuster, P.; Mueller, T.; Vos, A. In Vivo Safety Studies with SPBN GASGAS in the Frame of Oral Vaccination of Foxes and Raccoon Dogs against Rabies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkhouse, D.A.; Garcia, S.A.; Bongiorno, E.K.; Lebrun, A.; Faber, M.; Hooper, D.C. Expression of Interferon Gamma by a Recombinant Rabies Virus Strongly Attenuates the Pathogenicity of the Virus via Induction of Type I Interferon. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalos, D.; Grutzendler, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, J.V.; Zuo, Y.; Jung, S.; Littman, D.R.; Dustin, M.L.; Gan, W.-B. ATP Mediates Rapid Microglial Response to Local Brain Injury in Vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Préhaud, C.; Lay, S.; Dietzschold, B.; Lafon, M. Glycoprotein of Nonpathogenic Rabies Viruses Is a Key Determinant of Human Cell Apoptosis. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10537–10547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloul, L.; Lafon, M. Apoptosis and Rabies Virus Neuroinvasion. Biochimie 2003, 85, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, L.; Tseggai, T.; Dhingra, V.; Fu, Z.F. Rabies Virus-Induced Apoptosis Involves Caspase-Dependent and Caspase-Independent Pathways. Virus Res. 2006, 121, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suja, M.S.; Mahadevan, A.; Madhusudhana, S.N.; Vijayasarathi, S.K.; Shankar, S.K. Neuroanatomical Mapping of Rabies Nucleocapsid Viral Antigen Distribution and Apoptosis in Pathogenesis in Street Dog Rabies–an Immunohistochemical Study. Clin. Neuropathol. 2009, 28, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, K.; Hooper, D.C.; Spitsin, S.V.; Koprowski, H.; Dietzschold, B. Pathogenicity of Different Rabies Virus Variants Inversely Correlates with Apoptosis and Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Expression in Infected Primary Neuron Cultures. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Baer, G.M.; Winkler, W.G.; Bernard, K.W.; Gibert, C.G.; Chany, C.; Veronesi, R.; Group, T.C. Human Leukocyte Interferon Administration to Patients with Symptomatic and Suspected Rabies. Ann. Neurol. 1984, 16, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrell, M.J.; White, N.J.; Looareesuwan, S.; Phillips, R.E.; Suntharasamai, P.; Chanthavanich, P.; Riganti, M.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Nicholson, K.G.; Manatsathit, S. Failure of Interferon Alfa and Tribavirin in Rabies Encephalitis. Br. Med. J. 1989, 299, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, G.M.; Shaddock, J.H.; Williams, L.W. Prolonging Morbidity in Rabid Dogs by Intrathecal Injection of Attenuated Rabies Vaccine. Infect. Immun. 1975, 12, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, A.; Portocarrero, C.; Kean, R.B.; Barkhouse, D.A.; Faber, M.; Hooper, D.C. T-Bet Is Required for the Rapid Clearance of Attenuated Rabies Virus from Central Nervous System Tissue. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4358–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.P.; Shipley, R.; Drake, P.; Fooks, A.R.; Ma, J.; Banyard, A.C. Characterisation of a Live-Attenuated Rabies Virus Expressing a Secreted scFv for the Treatment of Rabies. Viruses 2023, 15, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Phares, T.W.; Koprowski, H.; Hooper, D.C. Failure to Open the Blood-Brain Barrier and Deliver Immune Effectors to Central Nervous System Tissues Leads to the Lethal Outcome of Silver-Haired Bat Rabies Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wen, Y.; Yang, S.; Xia, X.; Fu, Z.F. Intracerebral Administration of Recombinant Rabies Virus Expressing GM-CSF Prevents the Development of Rabies after Infection with Street Virus. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesdangsakonwut, S.; Sunden, Y.; Aoshima, K.; Iwaki, Y.; Okumura, M.; Sawa, H.; Umemura, T. Survival of Rabid Rabbits after Intrathecal Immunization. Neuropathology 2014, 34, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bertoune, M.A.R.; Kolbe, C.; Werner, A.-C.; Steinmetz, M.; Dietzschold, B.; Weihe, E. Combined Glycoprotein Mutations in Rabies Virus Promote Astrocyte Tropism and Protective CNS Immunity in Mice. Viruses 2026, 18, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020181

Bertoune MAR, Kolbe C, Werner A-C, Steinmetz M, Dietzschold B, Weihe E. Combined Glycoprotein Mutations in Rabies Virus Promote Astrocyte Tropism and Protective CNS Immunity in Mice. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020181

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertoune, Mirjam Anna Rita, Corinna Kolbe, Ann-Cathrin Werner, Maren Steinmetz, Bernhard Dietzschold, and Eberhard Weihe. 2026. "Combined Glycoprotein Mutations in Rabies Virus Promote Astrocyte Tropism and Protective CNS Immunity in Mice" Viruses 18, no. 2: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020181

APA StyleBertoune, M. A. R., Kolbe, C., Werner, A.-C., Steinmetz, M., Dietzschold, B., & Weihe, E. (2026). Combined Glycoprotein Mutations in Rabies Virus Promote Astrocyte Tropism and Protective CNS Immunity in Mice. Viruses, 18(2), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020181