Diverse Temperate Coliphages of the Urinary Tract

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prophage and CRISPR Prediction

2.2. Phage Induction

2.3. Phage DNA Extraction, Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

2.4. Phage Host Range

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.6. Phage Genome Analysis

3. Results

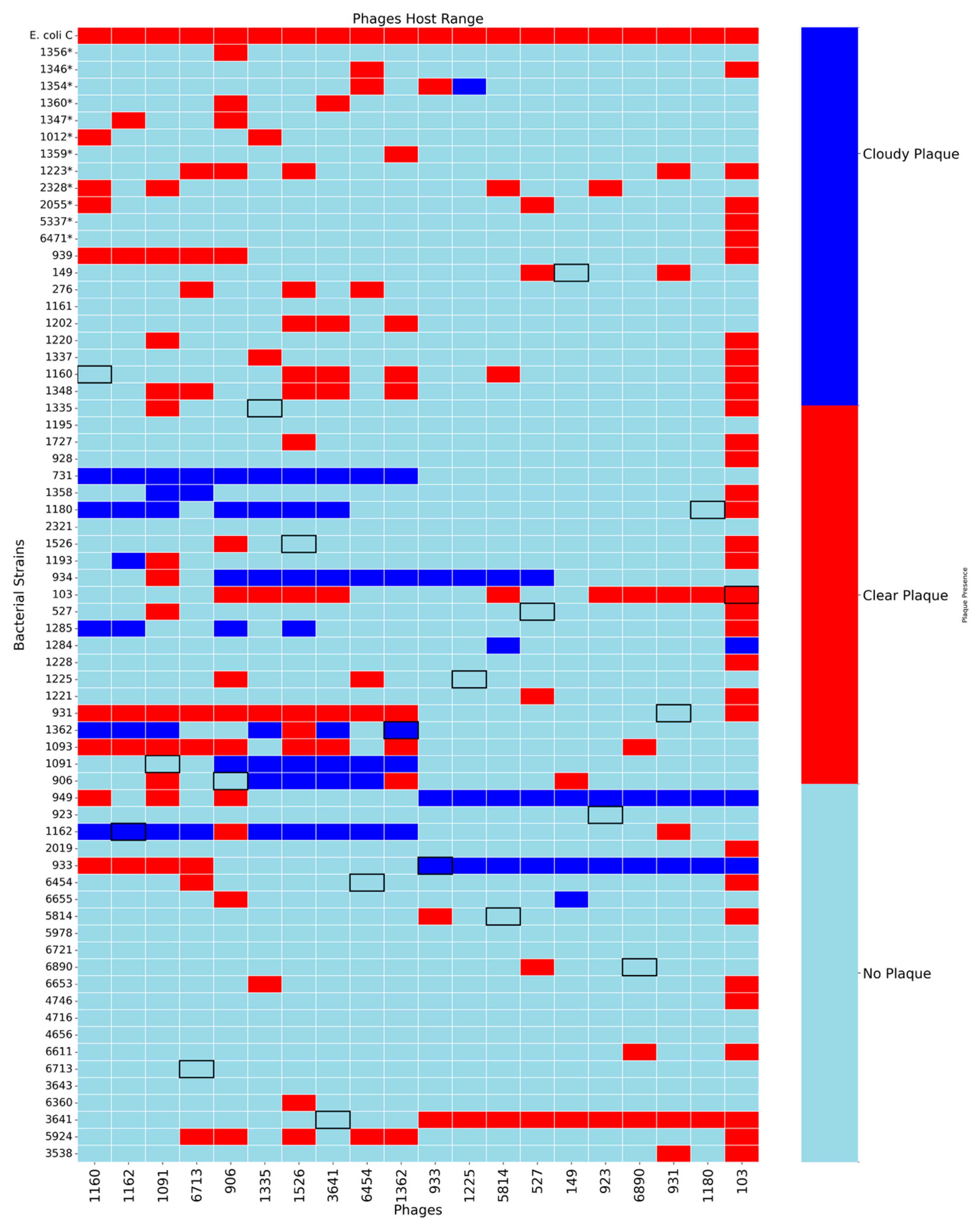

3.1. Host Range Analysis

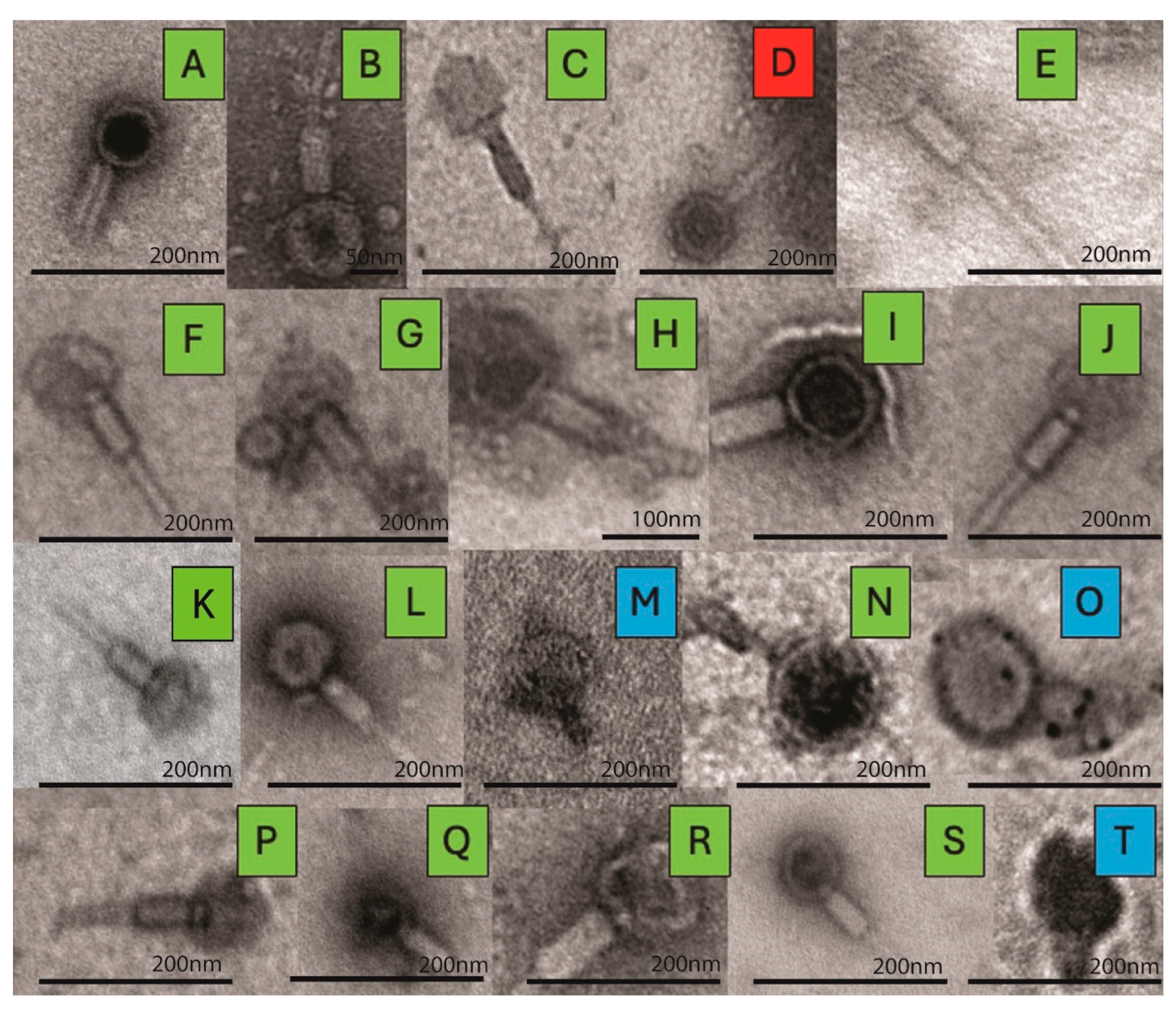

3.2. TEM Imaging

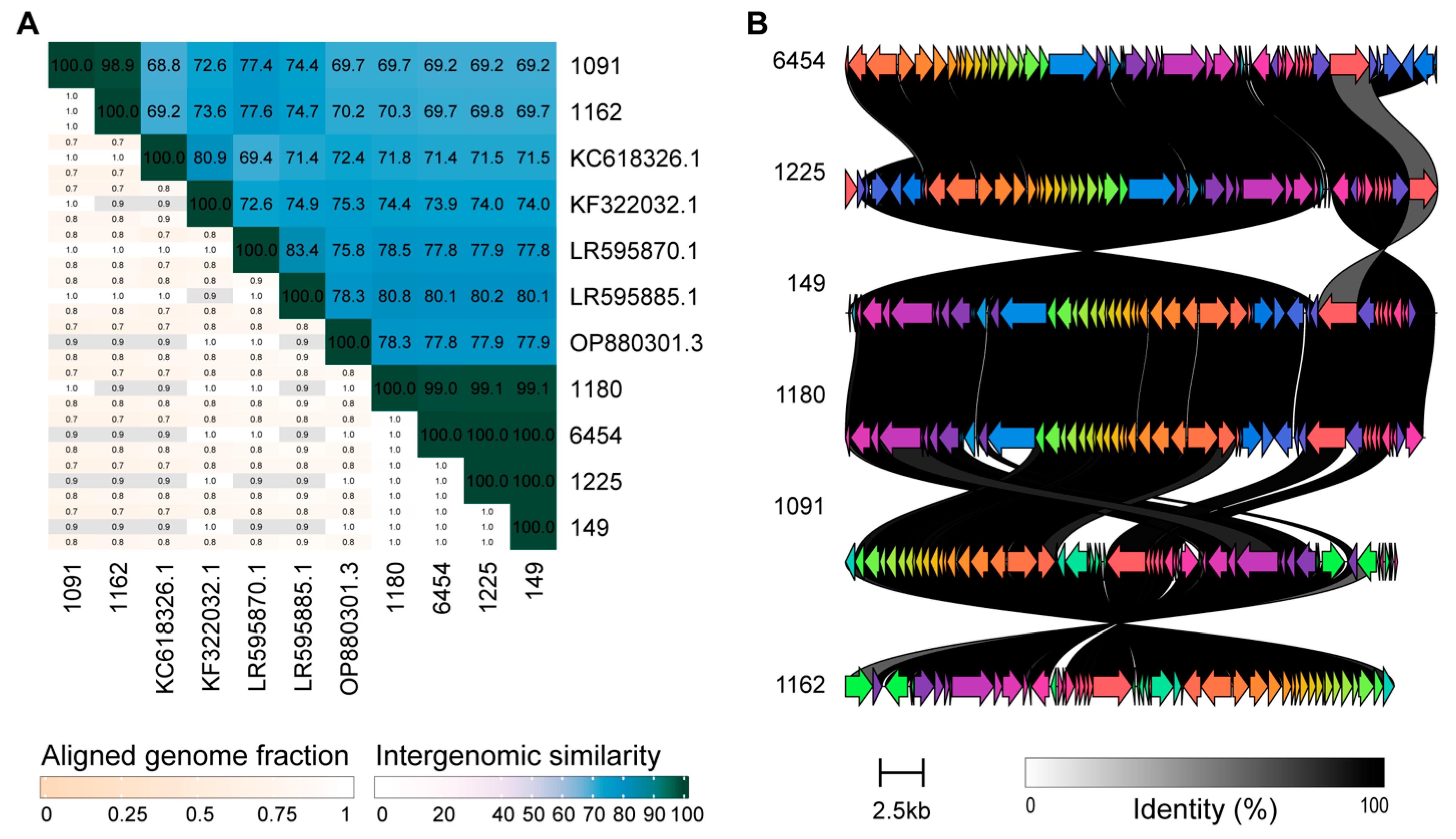

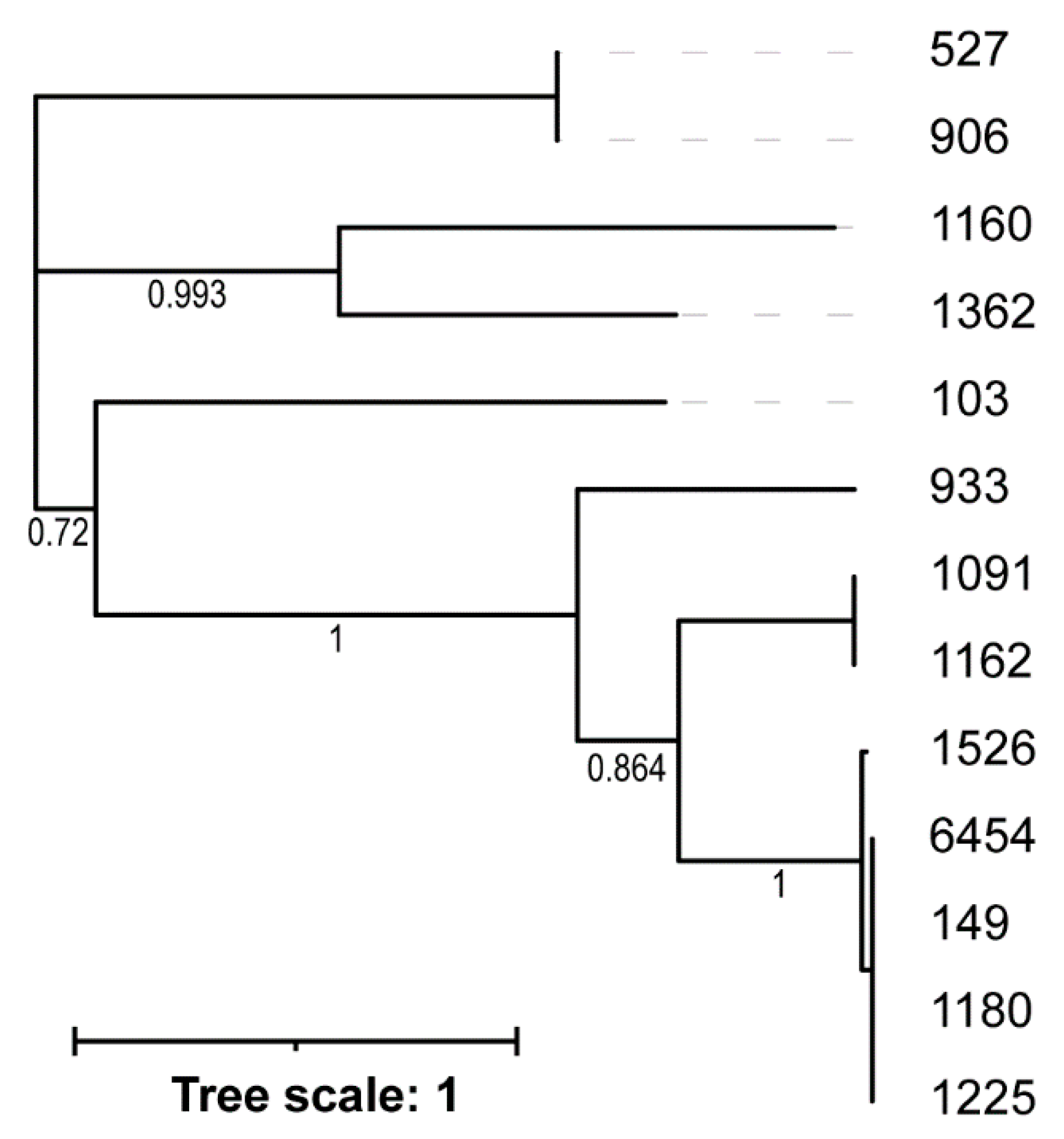

3.3. Genome Sequence Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medina, M.; Castillo-Pino, E. An Introduction to the Epidemiology and Burden of Urinary Tract Infections. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2019, 11, 1756287219832172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-White, K.J.; Gao, X.; Lin, H.; Fok, C.S.; Ghanayem, K.; Mueller, E.R.; Dong, Q.; Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J. Urinary Microbes and Postoperative Urinary Tract Infection Risk in Urogynecologic Surgical Patients. Int. Urogynecology J. 2018, 29, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretto, A.; Miller-Ensminger, T.; Ene, A.; Merchant, Z.; Shah, A.; Gerodias, A.; Biancofiori, A.; Canchola, S.; Canchola, S.; Castillo, E.; et al. Genomic Survey of E. coli from the Bladders of Women with and Without Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.K.; Hilt, E.E.; Thomas-White, K.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. The Urobiome of Continent Adult Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Bernheim, A.; Rocha, E.P.C. Genetic and Life-History Traits Associated with the Distribution of Prophages in Bacteria. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2744–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Perrin, A.; De Sousa, J.A.M.; Vangchhia, B.; Burn, S.; O’Brien, C.L.; Denamur, E.; Gordon, D.; Rocha, E.P. Phylogenetic Background and Habitat Drive the Genetic Diversification of Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrindt, U.; Agerer, F.; Michaelis, K.; Janka, A.; Buchrieser, C.; Samuelson, M.; Svanborg, C.; Gottschalk, G.; Karch, H.; Hacker, J. Analysis of Genome Plasticity in Pathogenic and Commensal Escherichia coli Isolates by Use of DNA Arrays. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, O.; Landan, G.; Dagan, T. Phylogenomic Networks Reveal Limited Phylogenetic Range of Lateral Gene Transfer by Transduction. ISME J. 2017, 11, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Leal, G.; Camelo-Valera, L.C.; Hurtado-Ramírez, J.M.; Verleyen, J.; Castillo-Ramírez, S.; Reyes-Muñoz, A. Mining of Thousands of Prokaryotic Genomes Reveals High Abundance of Prophages with a Strictly Narrow Host Range. mSystems 2022, 7, e00326-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molari, M.; Shaw, L.P.; Neher, R.A. Quantifying the Evolutionary Dynamics of Structure and Content in Closely Related E. coli Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2025, 42, msae272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannattasio-Ferraz, S.; Ene, A.; Gomes, V.J.; Queiroz, C.O.; Maskeri, L.; Oliveira, A.P.; Putonti, C.; Barbosa-Stancioli, E.F. Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Urine of Healthy Bovine Have Potential as Emerging Human and Bovine Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 764760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K.; Lu, Y.T.; Brenner, T.; Falardeau, J.; Wang, S. Prophage Diversity Across Salmonella and Verotoxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Agricultural Niches of British Columbia, Canada. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 853703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Makino, K.; Ohnishi, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Ishii, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Han, C.G.; Ohtsubo, E.; Nakayama, K.; Murata, T.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Genomic Comparison with a Laboratory Strain K-12. DNA Res. Int. J. Rapid Publ. Rep. Genes Genomes 2001, 8, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Ensminger, T.; Garretto, A.; Brenner, J.; Thomas-White, K.; Zambom, A.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Bacteriophages of the Urinary Microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00738-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, E.; Merchant, Z.; Ene, A.; Miller-Ensminger, T.; Johnson, G.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Coliphages of the Human Urinary Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramisetty, B.C.M.; Sudhakari, P.A. Bacterial “Grounded” Prophages: Hotspots for Genetic Renovation and Innovation. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, L.R.; Laub, M.T. E. coli Prophages Encode an Arsenal of Defense Systems to Protect against Temperate Phages. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1004–1018.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy-Denomy, J.; Davidson, A.R. When a Virus Is Not a Parasite: The Beneficial Effects of Prophages on Bacterial Fitness. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.; Brockhurst, M.A. Ecological and Evolutionary Benefits of Temperate Phage: What Does or Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Stronger. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2017, 39, 1700112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederberg, E.M.; Lederberg, J. Genetic studies of lysogenicity in Escherichia coli. Genetics 1953, 38, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobay, L.-M.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Touchon, M. The Adaptation of Temperate Bacteriophages to Their Host Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gallardo, O.; August, E.; Dassa, B.; Court, D.L.; Stavans, J.; Arbel-Goren, R. Stability and Gene Strand Bias of Lambda Prophages and Chromosome Organization in Escherichia coli. mBio 2024, 15, e0207823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.M.; Thormann, K.; Frunzke, J. Impact of Spontaneous Prophage Induction on the Fitness of Bacterial Populations and Host-Microbe Interactions. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, M.; Hewson, I.; Felts, B.; Mahaffy, J.M.; Nulton, J.; Salamon, P.; Rohwer, F. Metagenomic Analyses of an Uncultured Viral Community from Human Feces. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 6220–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A.; Haynes, M.; Hanson, N.; Angly, F.E.; Heath, A.C.; Rohwer, F.; Gordon, J.I. Viruses in the Faecal Microbiota of Monozygotic Twins and Their Mothers. Nature 2010, 466, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minot, S.; Sinha, R.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Wu, G.D.; Lewis, J.D.; Bushman, F.D. The Human Gut Virome: Inter-Individual Variation and Dynamic Response to Diet. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A.; McKeithen-Mead, S.; Shi, H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Huang, K.C.; Good, B.H. Abundance Measurements Reveal the Balance between Lysis and Lysogeny in the Human Gut Microbiome. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 2282–2294.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda-Franco, L.; Dahlman, S.; Barr, J.J. The Gut Virome and the Relevance of Temperate Phages in Human Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1241058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrot, C.; Petit, M.-A. Signals Triggering Prophage Induction in the Gut Microbiota. Mol. Microbiol. 2022, 118, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretto, A.; Miller-Ensminger, T.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Bacteriophages of the Lower Urinary Tract. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Characterization of the ϕCTX-like Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phage Dobby Isolated from the Kidney Stone Microbiota. Access Microbiol. 2019, 1, e000002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brassil, B.; Mores, C.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Characterization and Spontaneous Induction of Urinary Tract Streptococcus Anginosus Prophages. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almosuli, M.; Kirtava, A.; Chkhotua, A.; Tsveniashvili, L.; Chanishvili, N.; Irfan, S.S.; Ng, E.; McIntyre, H.; Hockenberry, A.J.; Araujo, R.P.; et al. Urinary Bacteriophage Cooperation with Bacterial Pathogens during Human Urinary Tract Infections Supports Lysogenic Phage Therapy. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A Better, Faster Version of the PHAST Phage Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an Update of CRISRFinder, Includes a Portable Version, Enhanced Performance and Integrates Search for Cas Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W246–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): A Resource Combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. J. Comput. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.J.; Powell, C.S.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Mims, L.R.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Virus Taxonomy: The Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 54, D776–D789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, C.; Varsani, A.; Kropinski, A.M. VIRIDIC—A Novel Tool to Calculate the Intergenomic Similarities of Prokaryote-Infecting Viruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Chooi, Y.-H. Clinker & Clustermap.Js: Automatic Generation of Gene Cluster Comparison Figures. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2473–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Xie, R.; Zhang, Y.; Stubenrauch, C.; Lithgow, T. AcrHub: An Integrative Hub for Investigating, Predicting and Mapping Anti-CRISPR Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D630–D638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, G.; Sironi, G.; Bialy, H.; Calendar, R. Bacteriophage Lambda; Abortive Infection of Bacteria Lysogenic for Phage P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1970, 66, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toothman, P.; Herskowitz, I. Rex-Dependent Exclusion of Lambdoid Phages II. Determinants of Sensitivity to Exclusion. Virology 1980, 102, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.J.; Henning, U. The Immunity (Imm) Gene of Escherichia coli Bacteriophage T4. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 3472–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberto, J.; Weisberg, R.A.; Gottesman, M.E. Structure and Function of the Nun Gene and the Immunity Region of the Lambdoid Phage HK022. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 207, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uc-Mass, A.; Loeza, E.J.; De La Garza, M.; Guarneros, G.; Hernández-Sánchez, J.; Kameyama, L. An Orthologue of the Cor Gene Is Involved in the Exclusion of Temperate Lambdoid Phages. Evidence That Cor Inactivates FhuA Receptor Functions. Virology 2004, 329, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S.V.; Wenner, N.; Dulberger, C.L.; Rodwell, E.V.; Bowers-Barnard, A.; Quinones-Olvera, N.; Rigden, D.J.; Rubin, E.J.; Garner, E.C.; Baym, M.; et al. Prophages Encode Phage-Defense Systems with Cognate Self-Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1620–1633.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, F.; Depardieu, F.; Miele, S.; Dowding, J.; Laval, A.-L.; Lieberman, E.; Garry, D.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Bernheim, A.; Bikard, D. Phages and Their Satellites Encode Hotspots of Antiviral Systems. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 740–753.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A Roadmap for Genome-Based Phage Taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göller, P.C.; Haro-Moreno, J.M.; Rodriguez-Valera, F.; Loessner, M.J.; Gómez-Sanz, E. Uncovering a Hidden Diversity: Optimized Protocols for the Extraction of dsDNA Bacteriophages from Soil. Microbiome 2020, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtappels, D.; Fortuna, K.J.; Vallino, M.; Lavigne, R.; Wagemans, J. Isolation, Characterization and Genome Analysis of an Orphan Phage FoX4 of the New Foxquatrovirus Genus. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Diaz, M.; Bleriot, I.; Pacios, O.; Fernandez-Garcia, L.; Blasco, L.; Ambroa, A.; Ortiz-Cartagena, C.; Woodford, N.; Ellington, M.J.; Tomas, M. Molecular Characteristics of Phages Located in Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates: New Phage-Like Plasmids. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yong, S.; Zhou, X.; Shen, J. Characterization of a New Temperate Escherichia coli Phage vB_EcoP_ZX5 and Its Regulatory Protein. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Ensminger, T.; Garretto, A.; Stark, N.; Putonti, C. Mimicking Prophage Induction in the Body: Induction in the Lab with pH Gradients. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staji, H.; Rassouli, M.; Jourablou, S. Comparative Virulotyping and Phylogenomics of Escherichia coli Isolates from Urine Samples of Men and Women Suffering Urinary Tract Infections. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halaji, M.; Fayyazi, A.; Rajabnia, M.; Zare, D.; Pournajaf, A.; Ranjbar, R. Phylogenetic Group Distribution of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Related Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 790184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Massaro, C.; Giammanco, G.M.; Alduina, R.; Boussoualim, N. Phylogenetic Diversity, Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence of Escherichia coli Strains from Urinary Tract Infections in Algeria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahshouri, P.; Alikhani, M.Y.; Momtaz, H.E.; Doosti-Irani, A.; Shokoohizadeh, L. Analysis of Phylogroups, Biofilm Formation, Virulence Factors, Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular Typing of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Patients with Recurrent and Non-Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntynen, S.; Laanto, E.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M.; Díaz-Muñoz, S.L. Black Box of Phage-Bacterium Interactions: Exploring Alternative Phage Infection Strategies. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canchaya, C.; Proux, C.; Fournous, G.; Bruttin, A.; Brüssow, H. Prophage Genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2003, 67, 238–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.-J.; Henning, U. Superinfection Exclusion by T-Even-Type Coliphages. Trends Microbiol. 1994, 2, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R.; Fremaux, C.; Deveau, H.; Richards, M.; Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P. CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleška, M.; Guet, C.C. Effects of Mutations in Phage Restriction Sites during Escape from Restriction–Modification. Biol. Lett. 2017, 13, 20170646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochhauser, D.; Millman, A.; Sorek, R. The Defense Island Repertoire of the Escherichia coli Pan-Genome. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons, B.J.; Van Houte, S.; Westra, E.R.; Chevallereau, A. Ecology and Evolution of Phages Encoding Anti-CRISPR Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, G.E.; Calendar, R. Bacteriophage P2. Bacteriophage 2016, 6, e1145782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.H.; Dennis, J.J. Cangene Gold Medal Award Lecture—Genomic Analysis and Modification of Burkholderia Cepacia Complex Bacteriophages. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaer Tamar, E.; Kishony, R. Multistep Diversification in Spatiotemporal Bacterial-Phage Coevolution. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergueev, K.V.; Filippov, A.A.; Farlow, J.; Su, W.; Kvachadze, L.; Balarjishvili, N.; Kutateladze, M.; Nikolich, M.P. Correlation of Host Range Expansion of Therapeutic Bacteriophage Sb-1 with Allele State at a Hypervariable Repeat Locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01209-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.; He, X.; Tan, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, L.; Lux, R.; Shi, W.; Hu, F. Mapping the Tail Fiber as the Receptor Binding Protein Responsible for Differential Host Specificity of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Bacteriophages PaP1 and JG004. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, A.; Dion, M.; Deng, L.; Tremblay, D.; Moncaut, E.; Shah, S.A.; Stokholm, J.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Schjørring, S.; Bisgaard, H.; et al. Virulent Coliphages in 1-Year-Old Children Fecal Samples Are Fewer, but More Infectious than Temperate Coliphages. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, I.H.E.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Kropinski, A.M.; Nimtz, M.; Rohde, M.; van Raaij, M.J.; Wittmann, J. Still Something to Discover: Novel Insights into Escherichia coli Phage Diversity and Taxonomy. Viruses 2019, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.J.; Atkins, H.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L.; Aslam, S.; Putonti, C.; Doud, M.B.; Burnett, L.A. Phage Therapy for Urinary Tract Infections: Progress and Challenges Ahead. Int. Urogynecology J. 2025, 36, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacífico, C.; Hilbert, M.; Sofka, D.; Dinhopl, N.; Pap, I.-J.; Aspöck, C.; Carriço, J.A.; Hilbert, F. Natural Occurrence of Escherichia coli-Infecting Bacteriophages in Clinical Samples. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phage ID | Bacterial Strain | Bacterial Phylotype | Participant Symptom | No. Predicted Prophages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | UMB0103 | F | OAB | 3 |

| 1091 | UMB1091 | B23 | UTI | 5 |

| 149 | UMB0149 | A | OAB | 5 |

| 527 | UMB527 | A | OAB | 6 |

| 906 | UMB906 | B23 | UTI | 5 |

| 923 | UMB923 | B1 | UTI | 4 |

| 931 | UMB931 | D | UTI | 6 |

| 933 | UMB0933 | B22 | No LUTS | 3 |

| 1160 | UMB1160 | B23 | UTI | 6 |

| 1162 | UMB1162 | B23 | UTI | 6 |

| 1180 | UMB1180 | B1 | UTI | 2 |

| 1225 | UMB1225 | D | UTI | 2 |

| 1335 | UMB1335 | D | UTI | 6 |

| 1362 | UMB1362 | B1 | UTI | 3 |

| 1526 | UMB1526 | B23 | UTI | 2 |

| 3641 | UMB3641 | D | UUI | 4 |

| 5814 | UMB5814 | B23 | UUI | 2 |

| 6454 | UMB6454 | B2 | UTI | 5 |

| 6713 | UMB6713 | B23 | No LUTS | 4 |

| 6890 | UMB6890 | B23 | UUI | 4 |

| Phage ID | NCBI BLAST Results | ICTV TaxaBLAST Results | Predicted Tail Morphology c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Neighbor Strain (Genus; Accession No.) | Query Coverage | Percent Identity | Species Exemplar Virus (Genus; Accession No.) | Intergenomic Similarity b | ||

| 103 | MAG: Caudoviricetes sp. isolate MSP1011 (Uncharacterized; OR222389) | 64% | 80.37% | Escherichia phage 2H10 (Glaedevirus; LR595862.1) | 30.0 | |

| 1091 | Peduovirus P22H4 (Peduovirus; LR595869.1) | 80% | 97.66% | Enterobacteria phage fiAA91-ss (Peduovirus; KF322032.1) | 72.6 | M |

| 149 | Escherichia Phage 12W (Peduovirus; OM475434) | 77% | 96.80% | Escherichia phage P2_4E6b (Peduovirus; LR595885.1) | 80.1 | M |

| 527 | Escherichia phage phiv205-1 (Lederbergvirus; MN340231) | 51% | 96.32% | Enterobacteria phage HK620 (Lederbergvirus; AF335538.1) | 35.8 | P |

| 906 | Enterobacteria phage CUS-3 (Lederbergvirus; CP000711) | 56% | 96.05% | Enterobacteria phage HK620 (Lederbergvirus; AF335538.1) | 35.9 | P |

| 923 | Escherichia phage vB_EcoM-683R1 (Uncharacterized; ON470593) | 72% | 97.10% | Salmonella phage SEN34 (Brunovirus; KT630649.1) | 31.3 | M [55] |

| 931 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 2344_22993 (Uncharacterized; OP074524) | 92% | 99.97% | Escherichia phage P2 (Peduovirus; KC618326.1) | 4.7 | |

| 933 | MAG: Caudoviricetes sp. isolate ctZgU1 (Uncharacterized; BK021527) | 98% | 95.66% | Salmonella phage PsP3 (Eganvirus; AY135486.1) | 63.8 | |

| 1160 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 1228_163631 (Uncharacterized; OP073762) | 100% | 100% | Escherichia phage P2 (Peduovirus; KC618326.1) | 0.3 | |

| 1162 | Escherichia virus P2_2H4 (Peduovirus; LR595869) | 82% | 97.4% | Escherichia phage P2_2H1 (Peduovirus; LR595870.1) | 77.6 | M |

| 1180 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. Isolate 0195_16858 (Uncharacterized; OP073076) | 84% | 97.8% | Escherichia phage P2_4E6b (Peduovirus; LR595885.1) | 80.8 | |

| 1225 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 0195_16858 (Uncharacterized; OP073076) | 83% | 97.80% | Escherichia phage P2_4E6b (Peduovirus; LR595885.1) | 80.2 | |

| 1335 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 1105_17178 (Uncharacterized; OP073677) | 100% | 99.81% | - | - | |

| 1362 | Escherichia phage vB_EcoP_ZX5 (Uetakevirus; MW722083) | 100% | 100% | Escherichia phage phiV10 (Uetakevirus; DQ126339.2) | 59.5 | P [56] |

| 1526 | Escherichia phage vB_EcoM-12474III (Peduovirus; MK907237) | 74% | 97.59% | Yersinia phage GMG73 (Peduovirus; OP880301.3) | 45.2 | M |

| 3641 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 2344_22993 (Uncharacterized; OP074524) | 81% | 99.97% | Salmonella phage Fels2 (Felsduovirus; AE006468.2 a) | 1.2 | |

| 5814 | MAG: Caudoviricetes sp. isolate ctc4i17 (Uncharacterized; BK019137) | 70% | 98.26% | Salmonella phage Fels2 (Felsduovirus; AE006468.2 a) | 0.1 | |

| 6454 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 0195_16858 (Uncharacterized; OP073076) | 83% | 97.81% | Escherichia phage P2_4E6b (Peduovirus; LR595885.1) | 80.1 | |

| 6713 | MAG: Bacteriophage sp. isolate 1105_17178 (Uncharacterized; OP073677) | 79% | 100% | - | - | |

| 6890 | Escherichia phage D108 (Muvirus; GQ357916) | 96% | 96.52% | Escherichia phage Mu (Muvirus; AF083977.1) | 68.3 | M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Atkins, H.; Stegman, N.; Putonti, C. Diverse Temperate Coliphages of the Urinary Tract. Viruses 2026, 18, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020179

Atkins H, Stegman N, Putonti C. Diverse Temperate Coliphages of the Urinary Tract. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtkins, Haley, Natalie Stegman, and Catherine Putonti. 2026. "Diverse Temperate Coliphages of the Urinary Tract" Viruses 18, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020179

APA StyleAtkins, H., Stegman, N., & Putonti, C. (2026). Diverse Temperate Coliphages of the Urinary Tract. Viruses, 18(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020179