1. Introduction

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), classified within the genus Enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae, was first isolated in 1962 from pediatric patients presenting with mild respiratory illness in California, United States [

1,

2]. In the subsequent decades, EV-D68 was largely regarded as a virus of low pathogenic concern, predominantly linked to subclinical infection or mild upper respiratory tract infections, such as rhinitis and pharyngitis, which symptomatology often overlapped with that of the common cold [

2]. Seroepidemiological evidence indicates that children represent the primary reservoir for establishing population-wide immunity against EV-D68. Although adults remain susceptible to infection, pre-existing immunity and a more effective immune response typically confine EV-D68 infection to subclinical or mild presentations. This perception shifted markedly in 2014, when a widespread outbreak of EV-D68 across North America resulted in more than one thousand laboratory-confirmed cases, particularly among children, manifesting as severe respiratory diseases and a previously underrecognized neurological complication: acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a polio-like syndrome characterized by the acute onset of limb weakness and paralysis [

3,

4,

5]. This outbreak underscored the latent virulence of EV-D68 and prompted heightened scientific attention to its evolutionary dynamics and pathogenic mechanisms.

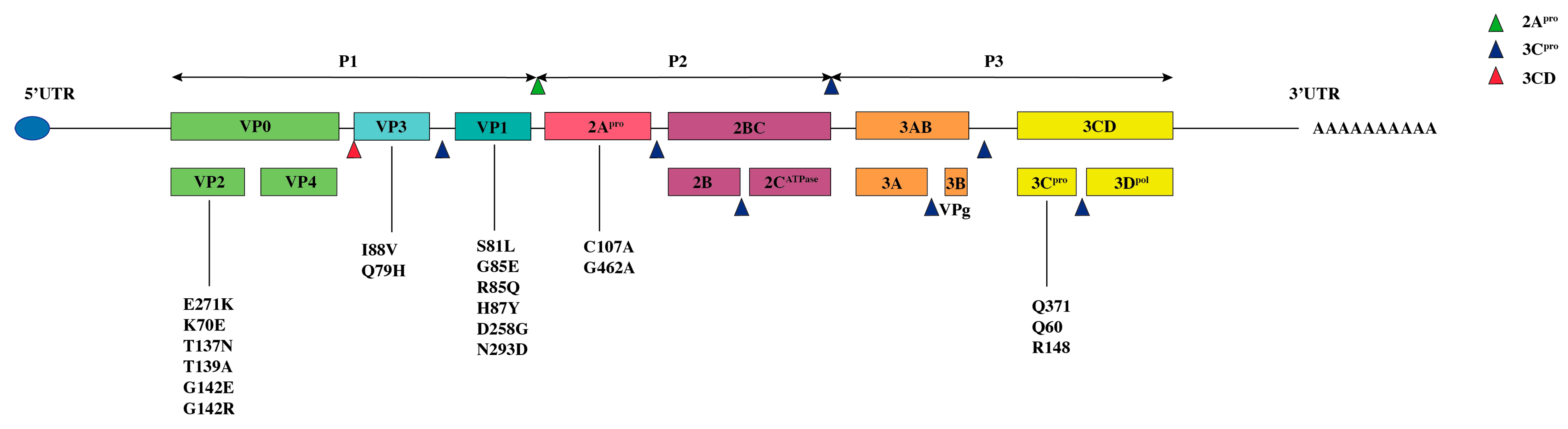

EV-D68 is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus containing a single open reading frame (ORF) that encodes four structural proteins (VP1–VP4) and seven nonstructural proteins (2A–2C and 3A–3D) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The structural proteins assemble to form the viral capsid, with VP1, VP2, and VP3 exposed on the virion surface, while VP4 is internally associated with the viral RNA. VP1 constitutes a major antigenic determinant recognized by the host immune system and is critically involved in receptor binding. Together with VP2 and VP3, it forms a surface “canyon” structure that facilitates specific attachment to host cell receptors and initiates viral entry [

6].

The cellular tropism and pathogenesis of EV-D68 are defined by its use of multiple entry receptors. Its major identified receptors are sialic acid, heparan sulfate, ICAM-5/Telencephalin, and MFSD6. Sialic acid, present on the respiratory epithelium, facilitates initial attachment. Heparan sulfate enhances binding and promotes neurotropism, while the protein receptor MFSD6 mediates entry into respiratory and neuronal cells, modulated by the VP1 BC-loop. Unlike related enteroviruses such as EV-A71 (using SCARB2/PSGL-1) or CVA16 (SCARB2/KREMEN1), EV-D68’s use of sialic acid and MFSD6 defines its respiratory tropism. Furthermore, its capacity to bind heparan sulfate and the neuronal adhesion molecule ICAM-5 significantly contributes to its neurovirulent potential, a distinctive feature that sets EV-D68 apart from most other members of the enterovirus genus.

The nonstructural proteins coordinate various aspects of viral replication: 3D acts as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), 2C and 3A contribute to the formation of replication complexes, and 2Apro and 3Cpro mediate polyprotein cleavage and host immune evasion.

The pathogenicity of EV-D68 is closely linked to specific genomic sequence elements that modulate viral replication, immune evasion, and host cell entry, thereby influencing clinical outcomes. This review summarizes current knowledge on the relationship between key sequence sites in the EV-D68 genome and viral pathogenicity, explores the underlying molecular mechanisms, and discusses the implications for surveillance and early response to future outbreaks.

2. Global Distribution of EV-D68 Subtypes

EV-D68 exhibits a global distribution, with distinct temporal and geographic patterns in subtype prevalence and transmission dynamics. Current understanding of its epidemiology is likely incomplete, as EV-D68 infection is frequently underdiagnosed in clinical settings. This diagnostic gap stems in part from the variable sensitivity of available assays to detect the virus and differentiate between its genetic lineages. A phylogenetic tree constructed from representative strains of major subtypes illustrates this global diversity (

Figure 3). Globally, subclade B3 has been the predominant lineage in recent years, while clade D (particularly D1) has been reported in Europe and the United States.

In North America, the United States experienced biennial epidemic peaks in 2014, 2016, and 2018. The 2014 outbreak was predominantly driven by subclade B1, with limited circulation of subclade B2. Subclade B3 first emerged as a predominant circulating lineage in 2016, while the D subtype was rarely detected in 2018 [

7,

8]. In Philadelphia, surveillance data from 2009 to 2018 revealed that the subclade B1 initially emerged in 2009, followed by annual epidemic peaks associated with AFM. By 2014, the subclade B1 had become the dominant lineage, whereas the B3 subtype persisted in circulation during 2016 and 2018 [

9]. Meanwhile, environmental surveillance in 2021 revealed the co-circulation of clade D and subclade B3 [

10]. In Canada, outbreak strains from 2014 primarily belonged to subclade B2 and were phylogenetically related to contemporaneous strains in the United States [

11].

In Europe, subclade B3 was identified in Italy in 2016 and was genetically similar to strains circulating in southern China, the United States, and the Netherlands in 2015 [

12]. In Spain during 2014–2016, subclades B2 and B3 were predominant, mirroring trends in the United States and other European countries. Subclade D1 emerged in 2017–2018 and was associated with pediatric cases presenting neurological symptoms, including meningitis and AFM [

13]. In Finland, subclade B3 constituted the majority of strains detected in 2018 [

14].

In Asia, widespread EV-D68 circulation in China was characterized by a shift in dominance from subclade A2 (2011–2013) to subclade B3 (2014–2018), with alternating detection of both lineages. Subclade B3 continued to circulate from 2017 to 2019, primarily causing mild acute lower respiratory tract infections in children, with rare reported neurological complications [

15,

16]. Surveillance in Shanghai from 2013 to 2020 identified the circulation of multiple subtypes, including D2, D3, and B3, albeit at low detection rates in children with respiratory tract infections. Subsequent sequence analysis suggested that recombination is a significant factor in shaping the viral genetic diversity [

17]. Furthermore, subclade B1 and B3 were detected in Taiwan in 2008 and in India in 2016, respectively [

18,

19].

In South America, subclade B3 was first identified among children with respiratory infections in Brazil in 2017 [

20]. Subsequent surveillance from 2021 to 2024 confirmed that B3 remains the dominant subtype in the country, alongside sporadic detections of D1 and D2 strains. In Africa, a study conducted in Senegal in 2016 identified EV-D68 in 7.4% (44/596) of patients presenting with influenza-like illness or acute flaccid paralysis, primarily affecting children under 5 years of age; all strains belonged to subclade B3 [

21]. More recent surveillance data from Nigeria (2020–2022) and Kenya (2021–2023) further clarify the regional distribution. In Nigeria, subclade B3 co-circulated with a novel subclade designated B4, while in Kenya, both B3 and D1 strains were detected, with B3 comprising approximately 80% of isolates.

Recombination plays a crucial role in EV-D68 evolution, and co-circulation of different clades provides favorable conditions for recombination by increasing the likelihood of dual infection of a single host cell. For example, in Shanghai, the co-circulation of B3, D2, and D3 from 2013 to 2020 led to the emergence of B3/D3 recombinant strains. Similarly, in the United States, co-circulation of B1 and B3 in 2016 resulted in B1/B3 recombinants, which were found to have enhanced replication efficiency in respiratory epithelial cells. More recently, surveillance by the Johns Hopkins Medical System in Maryland identified a novel A2/B3 recombinant strain circulating during 2025. In accordance with standard virological nomenclature, such recombinant strains are designated by indicating their parental clades to denote their genetic origins.

3. Structural Protein-Related Sites and Pathogenicity

3.1. VP1 Region

VP1 is a core structural and functional component of the EV-D68 capsid, playing indispensable roles in viral infectivity, antigenicity, and pathogenesis. The VP1 gene spans approximately 927 nucleotides and encodes the principal antigenic epitopes recognized by the host immune system. These epitopes not only serve as the primary target for neutralizing antibodies but also provide the basis for EV-D68 serotype classification, enabling discrimination between viral variants [

22,

23] (

Figure 2). Functionally, VP1 mediates viral receptor binding, immune evasion, and regulation of tissue tropism, making it the key structural protein influencing EV-D68 virulence.

Structurally, VP1 adopts a conserved β-barrel fold characteristic of enterovirus capsid proteins. Two surface-exposed loops—the BC-loop and DE-loop—are of particular functional importance. These loops are strategically positioned within the capsid architecture to facilitate two critical and often competing processes: interaction with host cell receptors and recognition by neutralizing antibodies [

23]. This dual role renders them essential determinants of both infectivity and antigenic profile.

Studies have shown that specific amino acid residues within VP1, particularly in the BC-loop region, can modulate receptor binding affinity through conformational adjustments. For example, interactions with the host receptor MFSD6 are influenced by the structural flexibility of this domain [

24]. Zhang et al., using neutralization escape mutant analysis, identified key residues in antigenic site I of the VP1 BC-loop—specifically G1085 and H1087 in the Fermon strain, and S1081 and R1085 in the clinical strain MO47—that map to the northern rim of the receptor-binding canyon. Mutations at these sites can alter sialic acid binding capacity and affect infection efficiency [

25]. Additionally, the E271K substitution in VP1 has been shown to enhance viral replication in neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH) and rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cell lines, potentially by strengthening heparan sulfate binding, which may promote spinal cord infection and neurovirulence [

26]. Collectively, these site-specific alterations in VP1 represent important molecular markers associated with changes in viral pathogenicity.

3.2. VP2 and VP3 Regions

VP2 is one of the major surface-exposed capsid proteins in EV-D68, cooperating with VP1 and VP3 to maintain virion integrity and stability. Encoded by a gene of approximately 750–840 base pairs, VP2—along with VP3 (encoded by a 690–780 bp gene)—serves roles beyond structural support, contributing to virion assembly, immune modulation, and recognition by neutralizing antibodies [

25] (

Figure 2). These proteins jointly shape the surface topology of the capsid, including the conserved canyon region essential for receptor binding, thereby influencing both infectivity and immune evasion.

Zhang et al. identified that residues in the EF loop of VP2 (T2137, G2142) and the BC loop of VP3 (Q3079) constitute antigenic sites II and IV. Mutations at these sites may reduce capsid stability and enhance immune evasion. For example, the T2137N substitution in VP2 was shown to diminish neutralization sensitivity, potentially facilitating viral spread within the host [

25]. Additionally, Chen et al. demonstrated that VP3 can suppress the interferon signaling pathway via interactions with host proteins [

27]. Yeh et al. reported that the I88 V mutation in VP3 attenuates neurovirulence in mouse models, likely by altering VP3 conformation and impairing binding to neuronal surface receptors. A strain carrying this mutation (US/MO-14-18949) exhibited significantly reduced neurological pathogenicity [

28]. Thus, VP2 and VP3, which are implicated in the formation of the surface canyon, serve as critical determinants of EV-D68 virulence.

In contrast to the external location of VP2 and VP3, VP4 is anchored to the inner surface of the capsid, where it interacts directly with the viral RNA to form a stable nucleocapsid core [

25] (

Figure 2). This internal positioning suggests a role in genome protection from nucleases and in maintaining RNA organization during assembly and maturation. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed that the C-terminal α-helix of VP4 inserts into the interface of capsid pentamers and forms a hydrogen-bond network with VP2 and VP3, reinforcing capsid stability throughout the viral life cycle. Currently, no virulence determinants have been conclusively assigned to VP4, likely due to limited direct functional studies and sparse sequence analysis across strains.

4. Association Between Non-Structural Protein-Related Sites and Virulence

4.1. A Protease

EV-D68 2A protease (2Apro) is a non-structural protein belonging to the trypsin-like cysteine protease family, defined by a conserved catalytic triad and stringent substrate specificity. Its proteolytic activity depends on three essential residues—His21, Asp39, and Cys107—which function cooperatively: Asp39 stabilizes the imidazole ring of His21, enabling deprotonation of Cys107 to generate a nucleophilic thiolate ion responsible for scissile bond cleavage. This structurally conserved active site ensures consistent 2Apro function across EV-D68 strains and underpins its central role in viral replication and pathogenesis [

29,

30].

Beyond catalyzing polyprotein processing, 2Apro acts as a key mediator of innate immune evasion. A major mechanism involves the specific cleavage of host tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 (TRAF3), an adaptor protein essential for interferon (IFN) induction following viral RNA sensing. 2Apro recognizes and cleaves TRAF3 at glycine 462 (G462), a process strictly dependent on its own catalytic Cys107. Mutagenesis studies (e.g., C107A in 2Apro or G462A in TRAF3) confirm that ablation of this activity restores IFN production and attenuates viral evasion [

29].

Furthermore, 2Apro collaborates with the viral 3C protease (3Cpro) to dismantle host translation machinery. Together, they target two central translation regulators: La-related protein 1 (LARP1), which facilitates the translation of 5’TOP motif-containing mRNAs, and poly(A)-binding protein cytoplasmic 1 (PABPC1), which stabilizes mRNA circularization and promotes translation initiation. Cleavage of these factors disrupts cap-dependent translation, thereby shutting down host protein synthesis and redirecting ribosomal resources to viral RNA [

31]. This strategy not only cripples antiviral responses but also enhances viral protein production.

Although 2Apro mutations linked to virulence have so far been primarily associated with immune suppression, their multifaceted role in translational control implies broader contributions to pathogenicity that warrant further investigation.

4.2. C Protease

EV-D68 3C protease (3Cpro) is a multifunctional enzyme essential for viral replication, primarily responsible for cleaving the viral polyprotein into mature functional subunits. Beyond this canonical role, 3Cpro actively subverts host antiviral defenses through targeted cleavage of key immune-related host proteins. It further disrupts multiple cellular processes—including host translation, mitochondrial homeostasis, and inflammatory signaling—thereby reshaping the intracellular environment to favor viral persistence and propagation [

32,

33].

Structural studies indicate that the tertiary structure of 3Cpro varies among EV-D68 subtypes. For instance, the conformation of 3Cpro in Clade B1 differs from those in Clades A, B2, and B3, potentially influencing enzymatic efficiency and substrate specificity, which may contribute to differences in viral virulence [

34]. Functionally, Wang et al. showed that 3Cpro cleaves LARP1 at Q371 and also targets PABPC1, thereby liberating viral RNA from translational suppression and impairing host mRNA stability and cap-dependent initiation [

31]. In addition, 3Cpro cleaves the transcription factor TFEB at Q60, disrupting its interaction with Rag GTPases, which in turn impairs autophagy-lysosomal function and inhibits NF-κB activation. This attenuates inflammatory cytokine production and blunts the host antiviral response [

35]. Li et al. reported that the host E3 ligase adaptor Cullin 3 restricts EV-D68 replication by promoting ubiquitination and degradation of 3Cpro. The K148 residue of 3Cpro was identified as a major ubiquitination site, while mutation at the adjacent R148 site impaired proteolytic activity [

36].

Overall, 3Cpro appears to be critically involved in modulating virus-induced inflammatory pathways. Whether it also regulates cell death programs represents a promising direction for future investigation.

5. Untranslated Region Structure and Regulation of Viral Replication

The 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of EV-D68 is a non-coding RNA segment located at the 3′ end of the viral genome that functions as a critical regulatory hub for viral replication and host–pathogen interactions. Unlike coding regions, its biological activity derives from conserved higher-order RNA structures—including stem-loops, pseudoknots, and bulges—that mediate sequence-specific molecular recognition [

6]. These structural motifs contribute to genomic RNA stability and serve as docking platforms for host proteins, thereby bridging viral replication machinery with cellular pathways.

A study by Wang et al. elucidated a key mechanism by which the 3′-UTR subverts host antiviral defenses [

37]. They identified an evolutionarily conserved element within the EV-D68 3′-UTR that specifically binds core stress granule (SG) proteins—TIA1, HUR, and G3BP1. Stress granules are dynamic ribonucleoprotein aggregates that sequester viral components to restrict replication. By recruiting these SG factors, the 3′-UTR disrupts granule assembly, rendering the cell permissive to viral propagation, and underscoring its role as a virulence determinant.

In a complementary study, Wang et al. employed a reverse genetics system to characterize the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of EV-D68 [

38]. Through site-directed mutagenesis, they demonstrated that a single-nucleotide substitution (G394C) disrupts the secondary structure of the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), impairing cap-independent translation initiation. This structural perturbation significantly reduced viral protein synthesis and replication, highlighting functional synergy between the 5′- and 3′-UTRs in sustaining the viral lifecycle.

The conserved sequence and structural features of both UTRs across EV-D68 isolates further suggest a role in viral pathogenicity. Structural conservation likely ensures reliable interaction with host factors and promotes efficient replication, which collectively influence infectivity and disease severity.

6. Virulence-Associated Loci in Other Enteroviruses

Many enteroviruses engage host receptors through defined capsid surface regions, such as the VP1 BC loop in EV-D68 and the VP1 N-terminus in EV-A71. Key residues in these regions, including K140 and R22, are conserved across multiple viral species, suggesting a shared strategy for receptor utilization [

25]. For example, in Coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16), the VP1-N102D and VP1-E241K mutations are linked to viral attenuation [

39]. Similarly, the VP1 T78A/G88A substitution in EV-A71 impairs proteolytic maturation of the VP0 precursor, reducing binding to the receptor SCARB2 and diminishing viral attachment and internalization, thereby attenuating virulence [

40]. Moreover, certain distal capsid regions can modulate VP0 cleavage efficiency via conformational effects, influencing the yield of infectious virions—a mechanism conserved among multiple enteroviruses with differing virulence phenotypes [

41].

Zhang et al. identified that VP2 residue K140 is invariant in all KREMEN1-dependent enterovirus A members, including CVA2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 12, and is essential for receptor binding, infectivity, and pathogenicity in mice [

42]. Wang et al. reported that CVB3 exhibits polymorphism at VP3-234 (Q/N/V/D/E), with the Q234 variant conferring high-affinity binding to the CD55 receptor, potentially directing tissue tropism [

43].

Beyond structural proteins, non-structural elements also modulate virulence. Peng et al. demonstrated that 2A proteases of EV-A71 and CVB3 undergo ERK-dependent phosphorylation at serine/threonine residues. A non-phosphorylatable mutation (S/T125A) impaired 2A protease activity, viral replication, and pathogenicity—a finding conserved across enteroviruses [

30]. Zheng et al. showed that TRAF3 enhances STING-mediated antiviral responses against EV-A71, and that EV-D68 similarly activates the STING pathway but subverts it via 2A protease activity to facilitate immune evasion [

44].

Variations in untranslated regions (UTRs) also contribute to virulence differences. In CVB3, structural divergence in the 5′ UTR of the avirulent CVB3/GA strain reduces translational efficiency and neurovirulence [

45]. In CVA24v, specific 5′ UTR mutations are postulated to enhance transmissibility and virulence [

46]. Furthermore, ubiquitination sites targeted by the host factor ZYG11B are conserved among CVA6, CVA16, and EV-D68; their modification suppresses viral replication, indicating a broad regulatory role in virulence [

47].

Antigenic variation in VP1 underlies serotype-specific virulence in viruses such as EV-A71 and CVA16 [

48]. Insertion–deletion (InDel) hotspots in Enterovirus A genomes also contribute to host recognition and immune evasion, further driving phenotypic diversification [

49]. In Enterovirus B, specific virulence loci are associated with type 1 diabetes via islet autoimmunity [

50], while CVB3 carries determinants linked to myocarditis and neurological sequelae [

51]. Collectively, these findings underscore that virulence mechanisms identified in related enteroviruses may provide valuable insights for investigating pathogenicity determinants in EV-D68.

7. Literature Review of EV-D68 Virulence-Associated Sites

A systematic literature search was conducted using the Web of Science and PubMed databases for articles published between January 2010 and November 2025. Only English-language studies were included. The search identified 12 articles addressing virulence-associated sites in EV-D68. Of these, five investigated variations in structural proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3), four focused on sites in the 2A protease and 3C protease, and two examined sequence or structural elements in the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR (

Table 1).

8. Challenges and Future Directions

The RdRp of EV-D68 plays an essential yet paradoxical role in viral evolution: although indispensable for genome replication, its lack of proofreading activity results in exceptionally high mutation rates. Unlike DNA polymerases, RdRp introduces nucleotide substitutions, insertions, and deletions at frequencies vastly exceeding those in host genomes. This genetic instability drives the continuous emergence of novel viral variants but complicates the identification of definitive virulence determinants, as phenotypic outcomes are often obscured by concurrent mutations across the genome [

52].

EV-D68 pathogenicity is shaped by dynamic virus–host interactions, where demographic and immunological factors—such as young age, immunocompromised status, or pre-existing immunity—critically modulate severity. Capsid mutants that cause mild disease in immunologically mature hosts can lead to severe respiratory illness or AFM in immunologically naïve children. Similarly, interferon pathway deficiencies can worsen outcomes. Thus, virulence is not an intrinsic viral trait but emerges from the interplay of viral mutations and host susceptibility [

53].

Moreover, changes in EV-D68 pathogenicity rarely result from single amino acid or nucleotide substitutions. Instead, virulence commonly arises from the cumulative effects of multiple sites distributed across viral proteins—such as VP1, 3Cpro, and RdRp—acting in concert. It is proposed that the clinical phenotype of EV-D68 infection is determined by the combined effects of multiple virulence determinants.

In light of these complexities, several key challenges impede progress. First, the predictive power of virulence-associated site identification remains limited: not all molecular changes observed in the laboratory correlate with clinical outcomes in humans. Second, while emerging tools—such as organoid models and artificial intelligence (AI)—show promise for early detection of high-risk variants, their translation into actionable public health interventions requires systematic validation and standardization.

To address these gaps, future efforts should prioritize the establishment of multidisciplinary surveillance networks that integrate genomic, clinical, and epidemiological data. Such systems will enable real-time tracking of viral evolution and enhance the early detection of emerging pathogenic strains. Equally important is the alignment of experimental models with clinical realities, ensuring that insights derived from cell cultures or animal studies are validated against human infection data. By closing the loop between bench and bedside, the field can move from reactive outbreak response to proactive risk prediction and preparedness.

9. Conclusions

In contrast to EV-A71, China has not experienced large-scale outbreaks of EV-D68. Moving forward, surveillance of viral virulence should prioritize key regions—including structural proteins VP1–VP3, proteases 2Apro and 3Cpro, and non-coding regions. Greater emphasis must be placed on correlating molecular findings with clinical phenotypes through rigorous validation. For both known and potential virulence loci, future virological studies should consider the combinatorial effects of multiple sites, rather than analyzing them in isolation, to better understand the polygenic nature of EV-D68 pathogenicity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing— original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2704901), the Nantong Municipal Key Medical Discipline, and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L242052).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV-D68 | Enterovirus D68 |

| AFM | Acute flaccid myelitis |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| bp | Base pairs |

| 2Apro | 2A protease |

| TRAF3 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 |

| LARP1 | La-related protein 1 |

| PABPC1 | Poly A-binding protein cytoplasmic 1 |

| 3Cpro | 3C protease |

| 3′-UTR | 3′-untranslated region |

| 5′-UTR | 5′-untranslated region |

| SGs | Stress granules |

| EV-A71 | Enterovirus A71 |

| CVB3 | Coxsackievirus B3 |

| CVA | Coxsackievirus A |

| InDel | Insertion-deletion |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

References

- Woods Acevedo, M.A.; Lan, J.; Maya, S.; Jones, J.E.; Bosco, I.E.; Williams, J.V.; Freeman, M.C.; Dermody, T.S. Immune cells promote paralytic disease in mice infected with enterovirus D68. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e188495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, N.L.; Archer, J.; Park, S.; Singh, G.; McFadden, K.M.; Kimura, T.; Nicholes, K.; Simpson, A.; Kaelber, J.T.; Hawman, D.W.; et al. A self-amplifying RNA vaccine prevents enterovirus D68 infection and disease in preclinical models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadi1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messacar, K.; Matzinger, S.; Berg, K.; Weisbeck, K.; Butler, M.; Pysnack, N.; Nguyen-Tran, H.; Davizon, E.S.; Bankers, L.; Jung, S.A.; et al. Multimodal Surveillance Model for Enterovirus D68 Respiratory Disease and Acute Flaccid Myelitis among Children in Colorado, USA, 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, M.R.; Wright, P.F.; Hickey, W.F.; De Buysscher, T.; Boyd, K.L.; Crowe, J.E., Jr. Enterovirus D68 in the Anterior Horn Cells of a Child with Acute Flaccid Myelitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2059–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyda, A.; Stelzer-Braid, S.; Adam, D.; Chughtai, A.A.; MacIntyre, C.R. The association between acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68)—What is the evidence for causation? Eurosurveillance 2018, 23, 17-00310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Tapprich, W.E. RNA Structure in the 5′ Untranslated Region of Enterovirus D68 Strains with Differing Neurovirulence Phenotypes. Viruses 2023, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilrane, V.L.; Zhuge, J.; Huang, W.; Nolan, S.M.; Dhand, A.; Yin, C.; Salib, C.; Shakil, F.; Engel, H.; Fallon, J.T.; et al. Biennial Upsurge and Molecular Epidemiology of Enterovirus D68 Infection in New York, USA, 2014 to 2018. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00284-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhuge, J.; Huang, W.; Nolan, S.M.; Gilrane, V.L.; Yin, C.; Dimitrova, N.; Fallon, J.T. Enterovirus D68 Subclade B3 Strain Circulating and Causing an Outbreak in the United States in 2016. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uprety, P.; Curtis, D.; Elkan, M.; Fink, J.; Rajagopalan, R.; Zhao, C.; Bittinger, K.; Mitchell, S.; Ulloa, E.R.; Hopkins, S.; et al. Association of Enterovirus D68 with Acute Flaccid Myelitis, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2009–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1676–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedcastle, A.; Wilton, T.; Pegg, E.; Klapsa, D.; Bujaki, E.; Mate, R.; Fritzsche, M.; Majumdar, M.; Martin, J. Detection of Enterovirus D68 in Wastewater Samples from the UK between July and November 2021. Viruses 2022, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi, A.; Duvvuri, V.R.; Isabel, S.; Banh, P.; Li, A.; Peci, A.; Patel, S.N.; Gubbay, J.B. Global Distribution and Evolutionary History of Enterovirus D68, with Emphasis on the 2014 Outbreak in Ontario, Canada. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piralla, A.; Principi, N.; Ruggiero, L.; Girello, A.; Giardina, F.; De, S.E.; Caimmi, S.; Bianchini, S.; Marseglia, G.L.; Lunghi, G.; et al. Enterovirus-D68 (EV-D68) in pediatric patients with respiratory infection: The circulation of a new B3 clade in Italy. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 99, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanz, R.; Taravillo, I.; Reina, J.; Navascués, A.; Moreno-Docón, A.; Aranzamendi, M.; Romero, M.P.; Del, C.M.; Pérez-González, C.; Pérez-Castro, S.; et al. Enterovirus D68-associated respiratory and neurological illness in Spain, 2014–2018. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer-Braid, S.; Yeang, M.; Britton, P.N.; Kim, K.W.; Varadhan, H.; Andrews, P.I.; Briest, R.; Branley, J.; Balgahom, R.; Burrell, R.; et al. Circulation of enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) causing respiratory illness in New South Wales, Australia, between August 2018 and November 2019. Pathology 2022, 54, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, S.; Sun, B. Molecular epidemiology and recombination of enterovirus D68 in China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 115, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Ai, J.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Z. Clinical and molecular epidemiologic features of enterovirus D68 infection in children with acute lower respiratory tract infection in China. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lu, R.J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Shi, P.; Ao, Y.Y.; Cao, L.F.; Zhang, Y.L.; Tan, W.J.; Shen, J. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of enterovirus D68 from 2013 to 2020 in Shanghai. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.S.; Luo, S.T.; Tsao, K.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Lee, M.S. Genomic analysis of enterovirus D68, including one strain isolated from a child with Wilson’s disease in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, R.E.; Sabeena, S.; Robin, S.; Shaji, J.T.; Jayakrishnan, M.P.; Suresh, E.K.K.; Michael, C.J.; Aswathyraj, S.; Josmi, J.; Shahin, S.; et al. Genetic analysis of Enterovirus D68 associated with pneumonia in children from South India. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.R.J.; Santos, H.O.; Pereira, J.S.; Leite, A.B.; Nascimento, J.P.M.D.; Souza, J.V.C.; Lima, M.B.Z.; de Araújo, M.A.; Giovanetti, M.; Kallas, E.G.; et al. Enterovirus D68 Subgenotype B3 Circulation in Children with Acute Respiratory Illness in the State of Alagoas, Brazil. Viruses 2025, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, A.; Ndiaye, N.; Jallow, M.M.; Barry, M.A.; Touré, C.S.B.; Kebe, O.; Kiori, D.E.; Sy, S.; Dia, M.; Goudiaby, D.; et al. Enterovirus D68 Subclade B3 Circulation in Senegal, 2016: Detection from Influenza-like Illness and Acute Flaccid Paralysis Surveillance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Sun, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Qin, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. A Novel Peptide from VP1 of EV-D68 Exhibits Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity Against Human Enteroviruses. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Fokine, A.; Meng, G.; Shin, W.H.; Long, F.; Kuhn, R.J.; Kihara, D.; Rossmann, M.G. Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children. Science 2015, 347, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, D.; Zhou, J.; Ni, F.; Yu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xue, L.; et al. MFSD6 is an entry receptor for respiratory enterovirus D68. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Identification of four neutralizing antigenic sites on the enterovirus D68 capsid. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0160023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooksawasdi, N.A.S.; Meijer, A.; Bauer, L.; Oude, M.B.; Embregts, C.; Leijten, L.; Siegers, J.Y.; Laksono, B.M.; van Kuppeveld, F.; Kuiken, T.; et al. Enhanced Enterovirus D68 Replication in Neuroblastoma Cells Is Associated with a Cell Culture-Adaptive Amino Acid Substitution in VP1. mSphere 2020, 5, e00941-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, M.; Hou, B.; Liu, Z.; Tan, R.; Cui, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z. The structural protein VP3 of enterovirus D68 interacts with MAVS to inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0016325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.T.; Capponi, S.; Catching, A.; Bianco, S.; Andino, R. Mapping Attenuation Determinants in Enterovirus-D68. Viruses 2020, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Pang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, J.; Liu, P.; Tan, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. Enterovirus D68 Protease 2Apro Targets TRAF3 To Subvert Host Innate Immune Responses. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01856-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, W.; Niu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Xiong, R.; Zhang, P.; Luo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fan, C.; et al. Phosphorylation of enteroviral 2Apro at Ser/Thr125 benefits its proteolytic activity and viral pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z. EV-D68 cleaves LARP1 and PABPC1 by 3Cpro to redirect host mRNA translation machinery toward its genomic RNA. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzolino, V.N.; Shaqra, A.M.; Ali, A.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C.A. Elucidating the Substrate Envelope of Enterovirus 68-3C Protease: Structural Basis of Specificity and Potential Resistance. Viruses 2024, 16, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wei, W. Enterovirus D68 Infection Induces TDP-43 Cleavage, Aggregation, and Neurotoxicity. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0042523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, G.; Zhuge, J.; Nolan, S.M.; Dimitrova, N.; Fallon, J.T. Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis Reveals the Enterovirus D68 Isolates during the United States 2014 Outbreak Mainly Belong to a Novel Clade. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassey, A.; Pollack, N.; Wagner, M.A.; Wu, J.; Benton, A.; Jackson, W.T. Transcription factor EB (TFEB) interaction with RagC is disrupted during enterovirus D68 infection. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0055624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qu, L.; Tang, Y.; Ni, F.; Shen, S.; Guo, H.; Yu, X.F.; Wei, W. Cullin 3-mediated ubiquitination restricts enterovirus D68 replication and is counteracted by viral protease 3C. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0035425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, C.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Kang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. Typical Stress Granule Proteins Interact with the 3′ Untranslated Region of Enterovirus D68 To Inhibit Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e02041-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. A reverse genetics system for enterovirus D68 using human RNA polymerase I. Virus Genes 2018, 54, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, B.; Huo, Y.; Lu, J.; Guo, J.; Deng, M.; Li, P.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Meng, S.; et al. Amino acid substitutions in VP2, VP1, and 2C attenuate a Coxsackievirus A16 in mice. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 150, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Yi, D.; Zheng, R.; Liu, G.; Liu, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; et al. Novel virulence determinants in VP1 regulate the assembly of enterovirus-A71. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0165524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qian, S.; Du, Y.; Wu, J.; Rehemutula, H.; Meng, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Shen, S. A single amino acid mutation in VP1 of coxsackievirus A6 determining efficiency of VP0 cleavage and proliferation. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0012825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Yan, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, K.; Hao, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C. Completely conserved VP2 residue K140 of KREMEN1-dependent enteroviruses is critical for virus-receptor interactions and viral infection. mBio 2025, 16, e0304024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, G.; Song, H.; Shang, G.; Peng, R.; Qu, X.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; et al. Molecular basis of differential receptor usage for naturally occurring CD55-binding and -nonbinding coxsackievirus B3 strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118590119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Rui, Y.; Ye, R.; Xia, F.; Guo, F.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Lou, M.; Yu, X.F. TRAF3 activates STING-mediated suppression of EV-A71 and target of viral evasion. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.; Tapprich, W.E. Role of RNA Domain Structure and Orientation in the Coxsackievirus B3 Virulence Phenotype. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0044823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidi, P.; Panda, S.; Ray, A.; Mohanty, M.; Mandal, M.C.; Santra, D.; Moharana, B.; Nayak, B.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Mishra, B. Molecular characterization of coxsackievirus A24 variants isolated from an outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 49, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Mi, Z.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. ZYG11B suppresses multiple enteroviruses by triggering viral VP1 degradation. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0003025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Maisimu, M.; Ge, Z.; Xiao, S.; Wang, H. The Pathogenesis and Virulence of the Major Enterovirus Pathogens Associated with Severe Clinical Manifestations: A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2025, 14, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhache, W.; Symonds-Orr, W.; McCormick, L.; Dolan, P.T. Deep mutation, insertion and deletion scanning across the Enterovirus A proteome reveals constraints shaping viral evolution. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, S.R.; Roy, A.; Dance, B.; Ward, E.J.; Foskett, D.B.; Maxwell, A.J.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Kim, K.W.; Craig, M.E. Enteroviruses and risk of islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled observational studies detecting viral nucleic acids and proteins. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.B.; Shen, E.Q.L.; Melendez, M.; Mishra, N.; Lipkin, W.I.; Racaniello, V.R. Cross-Reactive Antibody Responses against Nonpoliovirus Enteroviruses. mBio 2022, 13, e0366021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dábilla, N.; Maya, S.; McNinch, C.; Eddens, T.; Dolan, P.T.; Freeman, M.C. Strain-Specific Tropism and Transcriptional Responses of Enterovirus D68 Infection in Human Spinal Cord Organoids. Preprint. bioRxiv 2025, 16, 1698639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengual-Chuliá, B.; Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Mira-Iglesias, A.; Cano, L.; García-Esteban, S.; Ferrús, M.L.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Díez-Domingo, J.; López-Labrador, F.X.; VAHNSI Network. Enterovirus D68 disease burden and epidemiology in hospital-admitted influenza-like illness, Valencia region of Spain, 2014-2020 influenza seasons. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |