AI-Based Respiratory Monitoring-Guided Evaluation of Rottlerin Therapy for PRRS in Grower–Finisher Pig Farms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Rottlerin-Lipid (AlimenWOW) Mixture

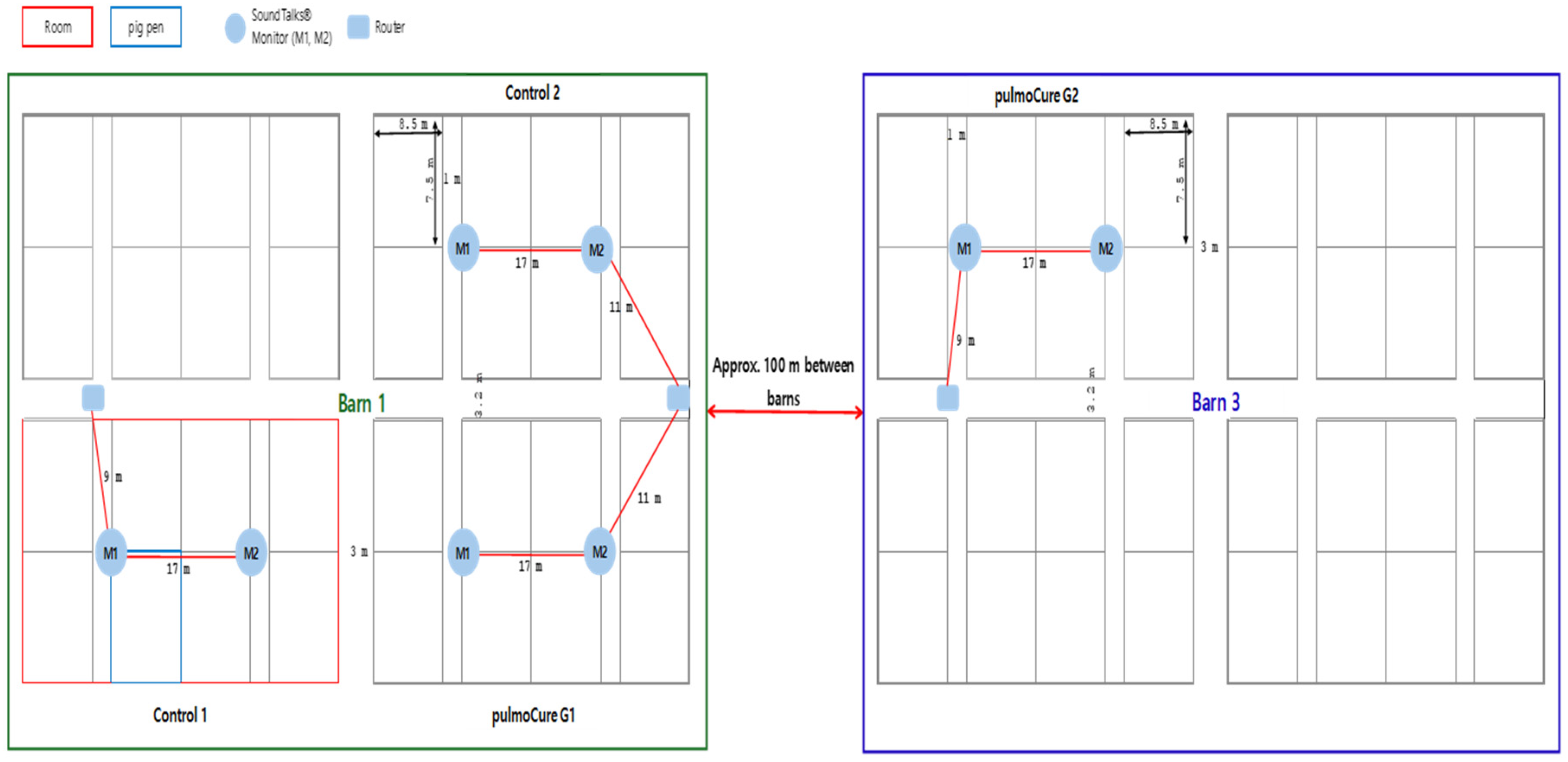

2.2. Farm, Animals, and Study Design

2.3. AI-Based Respiratory Health Monitoring

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. PRRSV Antigen Detection

2.6. Serological Analysis

2.7. Clinical Outcome Scoring

2.8. Economic Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

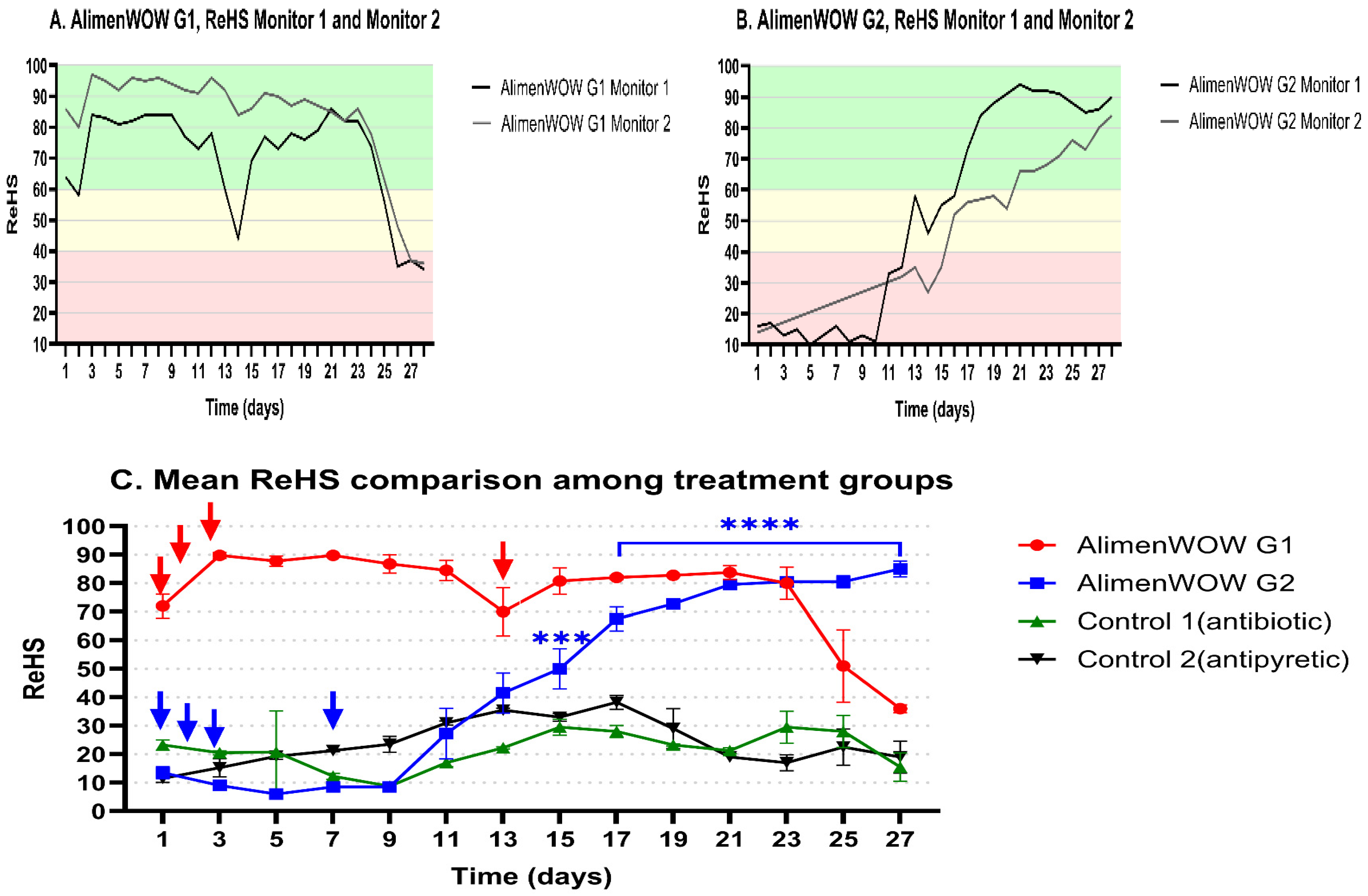

3.1. Effect of AlimenWOW on AI-Based Respiratory Health Indices

3.2. Effect of AlimenWOW on Mortality and Wasting

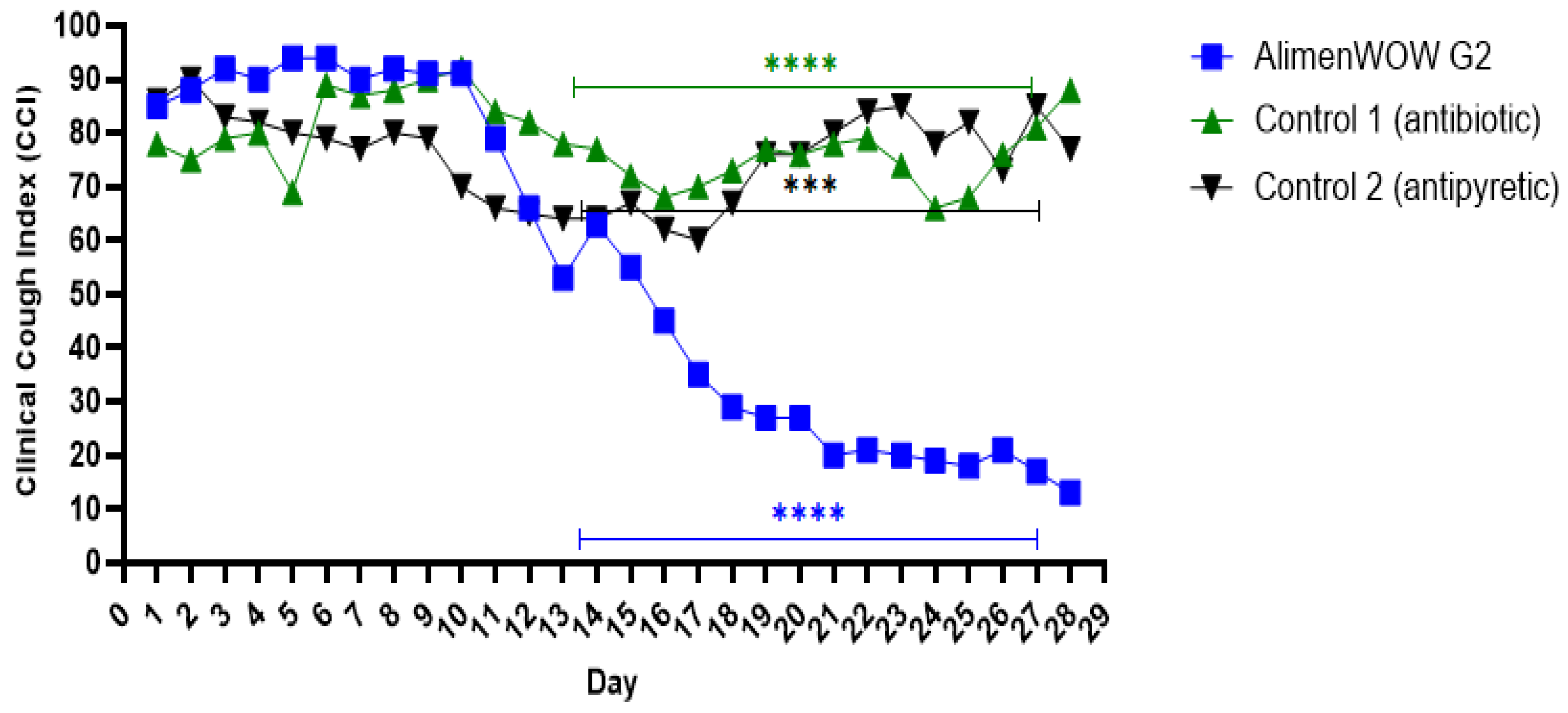

3.3. Effect of AlimenWOW on Clinical Cough Dynamics

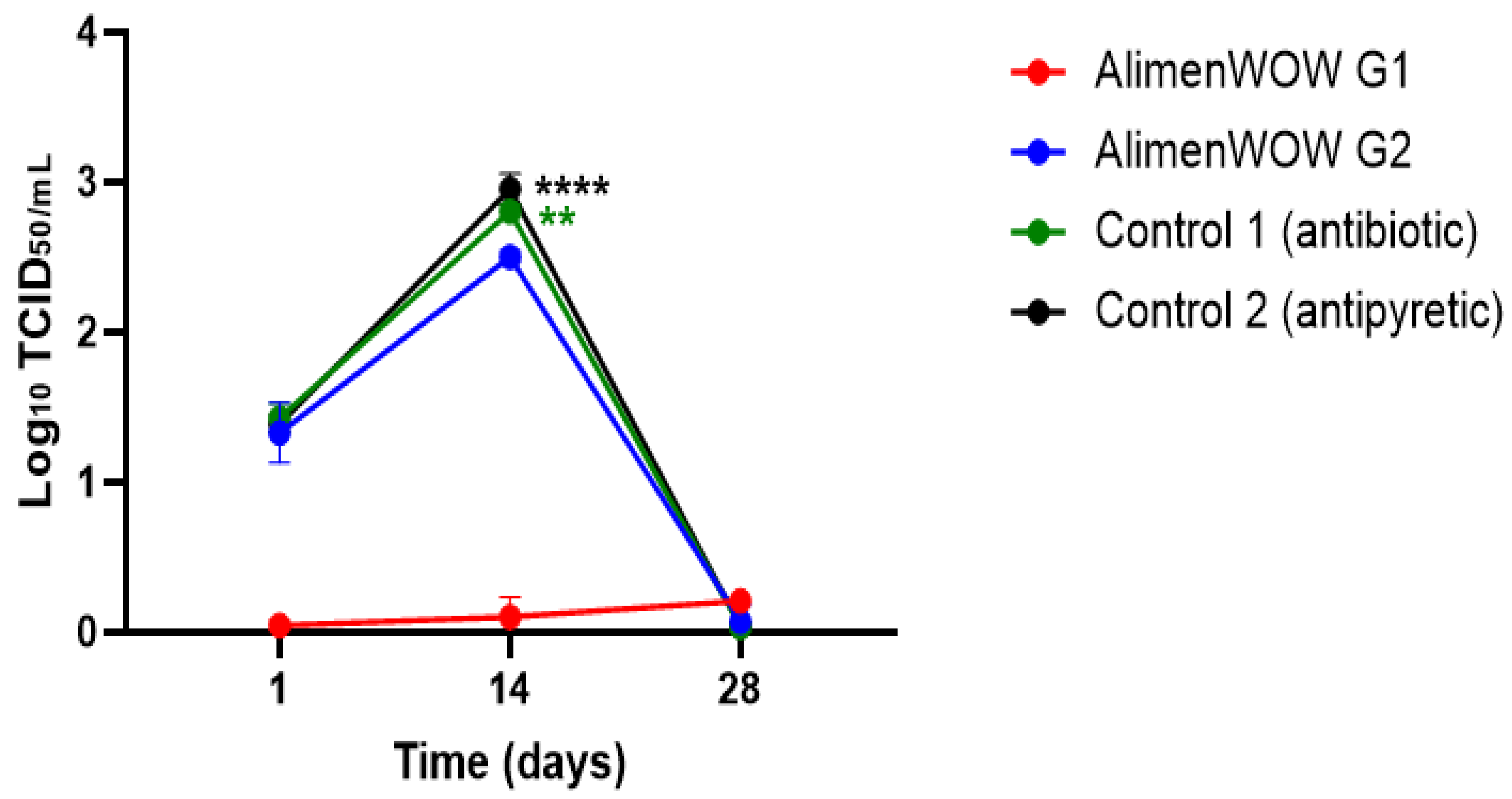

3.4. Reduction of PRRSV Load in Oral Fluid

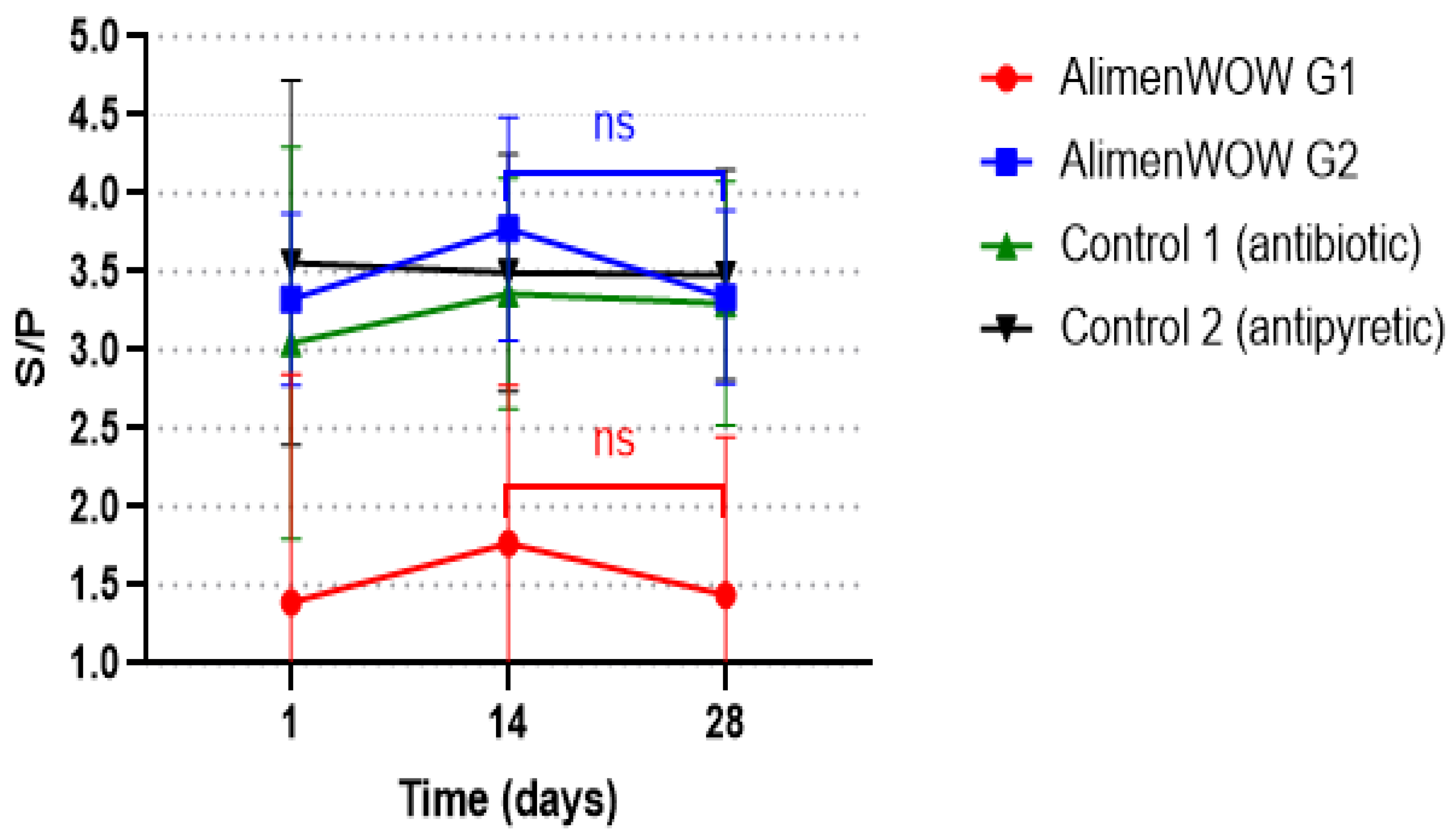

3.5. Effect of AlimenWOW on PRRSV-Specific Antibody Responses

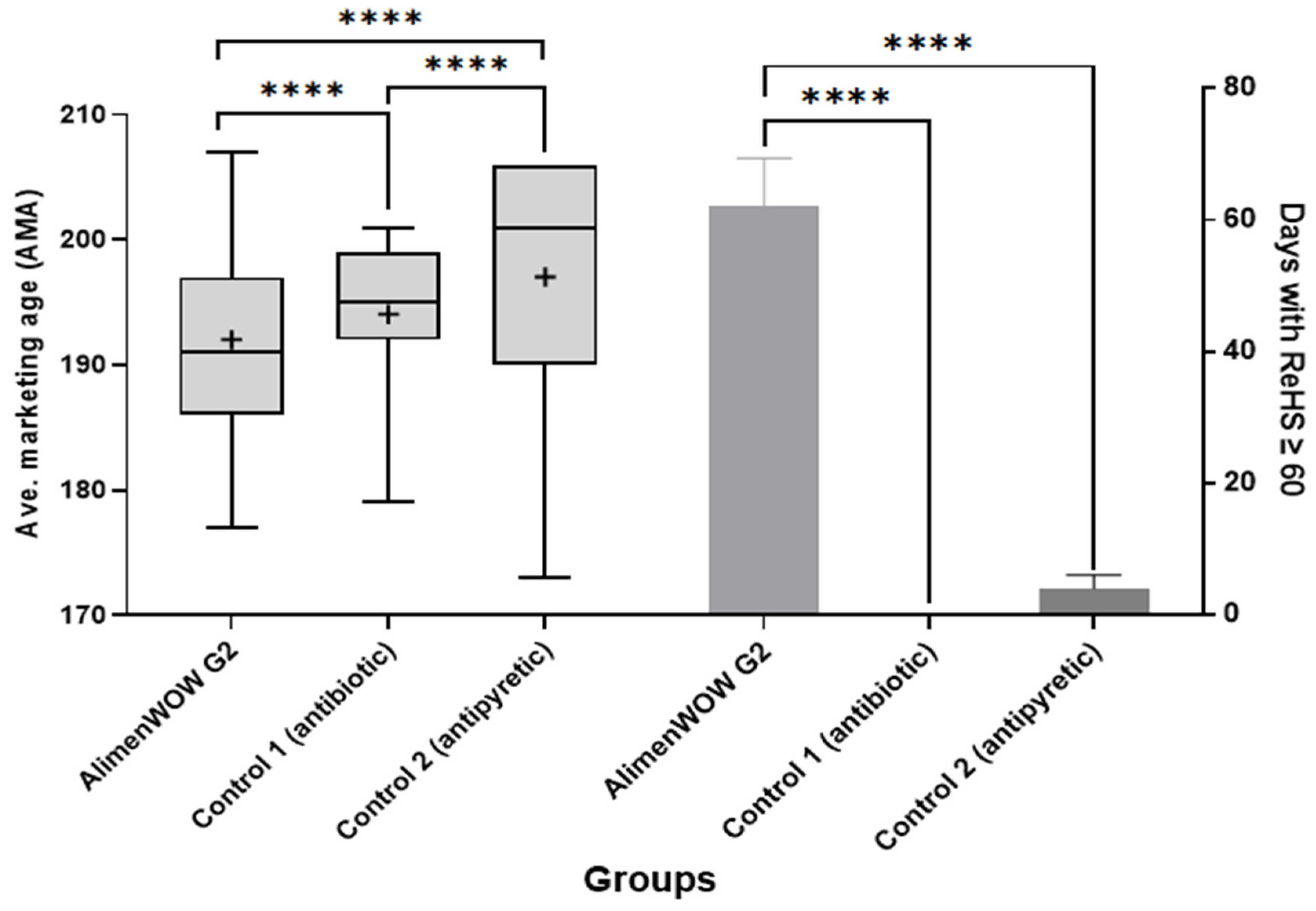

3.6. Economic Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanada, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakane, T.; Hirose, O.; Gojobori, T. The origin and evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, J.K.; Benfield, D.A.; Rowland, R.R.R. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: An update on an emerging and re-emerging viral disease of swine. Virus Res. 2010, 154, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, D.J.; Kliebenstein, J.B.; Neumann, E.J.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Rotto, H.F.; Yoder, T.K.; Wang, C.; Yeske, P.E.; Mowrer, C.L.; Haley, C.A. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. J. Swine Health Prod. 2013, 21, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemeke, O.H.; Holtkamp, D.J.; Silva, G.S.; Corzo, C.A. Economic impact of productivity losses attributable to PRRSV in the United States, 2016–2020. Prev. Vet. Med. 2025, 244, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathues, H.; Alarcon, P.; Rushton, J.; Jolie, R.; Fiebig, K.; Jimenez, M.; Geurts, V.; Nathues, C. Cost of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus at individual farm level—An economic disease model. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 142, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-C.; Kim, H.-J.; Jeong, C.-G.; Park, G.-S.; Choi, J.-S.; Kim, W.-I. Insight into the economic effects of a severe Korean PRRSV1 outbreak in a farrow-to-nursery farm. Animals 2022, 12, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-C.; Moon, S.-H.; Jeong, C.-G.; Park, G.-S.; Park, J.-Y.; Jeoung, H.-Y.; Shin, G.-E.; Ko, M.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.-K.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing and genetic characteristics of representative porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) isolates in Korea. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengeling, W.L.; Lager, K.M.; Vorwald, A.C. Diagnosis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1995, 7, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossow, K.D. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. Vet. Pathol. 1998, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiers, J.; Rogiers, C.; Saelens, X.; Vandekerckhove, L. A comprehensive review on PRRSV: Biology, diversity, pathogenesis, diagnostics, and vaccines. Vaccines 2024, 12, 942. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, E.L. Immunology of the porcine respiratory disease complex. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2001, 17, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanawongnuwech, R.; Brown, G.B.; Halbur, P.G.; Roth, J.A.; Royer, R.L.; Thacker, B.J. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-induced increase in susceptibility to Streptococcus suis infection. Vet. Pathol. 2000, 37, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, J.R.; Hoff, S.J.; Yoon, K.J.; Burkhardt, A.C.; Evans, R.B.; Zimmerman, J.J. Optimization of a sampling system for recovery and detection of airborne porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and swine influenza virus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4811–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.; Neira, V.; Corzo, C.A.; VanderWaal, K. Environmental drivers of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus transmission in the United States. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1158306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.Q.; Heber, A.J.; Diehl, C.A.; Lim, T.T. Ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide release from pig manure in under-floor deep pits. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2000, 77, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, J.; Heo, Y.; Lee, K.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.; Yoon, C. Evaluation of short-term exposure levels on ammonia and hydrogen sulfide during manure-handling processes at livestock farms. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donham, K.J.; Haglind, P.; Peterson, Y.; Rylander, R.; Belin, L. Environmental and health studies of farm workers in Swedish swine confinement buildings. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1988, 45, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, G. Investigations of factors affecting air pollutants in animal house. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 1997, 4, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Huang, L.; Gao, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X. Ammonia Exposure Induced Cilia Dysfunction of Nasal Mucosa in Piglets. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1705387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donham, K.J.; Reynolds, S.J.; Whitten, P.; Merchant, J.A.; Burmeister, L.; Popendorf, W.J. Respiratory dysfunction in swine production facility workers: Dose–response relationships of environmental exposures and pulmonary function. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1995, 27, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. Respiratory Health Hazards in Agriculture. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, S1–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, J.J.; Karriker, L.A.; Ramirez, A.; Schwartz, K.J.; Stevenson, G.W.; Zhang, J. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 685–720. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Han, X.; Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y. Recent advances in the study of NADC34-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 950402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Geelen, A.G.M.; Anderson, T.K.; Lager, K.M.; Das, P.B.; Otis, N.J.; Montiel, N.A.; Miller, L.C.; Brockmeier, S.L.; Zhang, J.; Gauger, P.C.; et al. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: Evolution and recombination yield distinct ORF5 RFLP 1-7-4 viruses with individual pathogenicity. Virology 2018, 513, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Guo, X.; Han, J.; Yang, H. Emergence and spread of NADC34-like PRRSV in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Kim, H.J.; Moon, S.H.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, W.I. First identification and genomic characterization of NADC34-like PRRSV strains isolated from MLV-vaccinated pigs in Korea. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 9995433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Eo, Y.; Lee, D.; Jang, G.; Min, K.-C.; Choi, A.K.; Won, H.; Cho, J.; Kang, S.C.; Lee, C. Comparative Genomic and Biological Investigation of NADC30- and NADC34-Like PRRSV Strains Isolated in South Korea. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2025, 2025, 9015349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Current Status of Vaccines for Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome: Interferon Response, Immunological Overview, and Future Prospects. Vaccines 2024, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charerntantanakul, W. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccines: Immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety aspects. World J. Virol. 2012, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.I.; Lee, D.S.; Johnson, W.; Roof, M.; Cha, S.H.; Yoon, K.J. Effect of genotypic and biotypic differences among PRRS viruses on the serologic assessment of pigs for virus infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 123, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.L.X.; Kwon, B.; Yoon, K.J.; Laegreid, W.W.; Pattnaik, A.K.; Osorio, F.A. Immune evasion of PRRSV through glycan shielding involves GP5 and GP3. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 5555–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Ji, G.; Tian, K. Commercial vaccines provide limited protection to NADC30-like PRRSV infection. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5540–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Yang, H. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Modified Live Virus Vaccine: A “Leaky” Vac-cine with Debatable Efficacy and Safety. Vaccines 2021, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Madson, D.; Harmon, K.; Gauger, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Recombination between vaccine and field strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2335–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Feng, W. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus: Immune Escape and Application of Reverse Genetics in Attenuated Live Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2021, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Nan, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, E.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y. Antiviral strategies against PRRSV infection. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paccetti-Alves, I.; Batista, M.S.P.; Pimpão, C.; Victor, B.L.; Soveral, G. Unraveling the Aquaporin-3 Inhibitory Effect of Rottlerin by Experimental and Computational Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, V.; Singh, S.; Gupta, P. Pharmacological activities of rottlerin: A comprehensive review. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117993. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, K.; Kruhlak, M.J.; Erlandsen, S.L.; Shaw, S. Selective inhibition by rottlerin of macropinocytosis in monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunology 2005, 116, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.L.; Oh, C.I.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, J.C.; Choi, H.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Choi, I.S.; Song, C.S.; Lee, J.B.; Park, S.Y. Inhibition of endocytosis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by rottlerin and its potential prophylactic administration in piglets. Antivir. Res. 2021, 195, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.L.; Choi, J.-C.; Lee, J.-B.; Park, S.-Y.; Oh, C.-I. Rottlerin inhibits macropinocytosis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus through the PKCδ–cofilin signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, T.; Song, Z. Broad-spectrum antiviral effects of rottlerin. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.C.; Jung, S.W.; Choi, I.Y.; Kang, Y.L.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.W.; Park, S.Y.; Song, C.S.; Choi, I.S.; Lee, J.B.; et al. Rottlerin liposome inhibits the endocytosis of feline coronavirus infection. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maioli, E.; Torricelli, C.; Valacchi, G. Rottlerin and cancer: Novel evidence and mechanisms. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 350826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, R.; Rasul, A.; Asghar, S.; Kovács, A.; Berkó, S.; Budai-Szűcs, M. Lipid Nanoparticles: An Effective Tool to Im-prove the Bioavailability of Nutraceuticals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. General introduction to precision livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagua, E.B.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Vandermeulen, J.; Norton, T.; Exadaktylos, V. Artificial intelligence for automatic monitoring of respiratory health conditions in smart swine farming. Animals 2023, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pann, V.; Kwon, K.-S.; Kim, B.; Jang, D.-H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-B. Robustness of CNN-Based Model Assessment for Pig Vocalization Classification across Diverse Acoustic Environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2026, 240, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Tu, D.; Shen, W.; Bao, J. Recognition of sick pig cough sounds based on convolutional neural network in field situations. Inf. Process. Agric. 2021, 8, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamsakul, P.; Yano, T.; Junchum, K.; Anukool, W.; Kittiwarn, N. Machine Learning-Based Detection of Pig Coughs and Their Association with Respiratory Diseases in Fattening Pigs. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddicks, M.; Feicht, F.; Beckjunker, J.; Genzow, M.; Alonso, C.; Reese, S.; Ritzmann, M.; Stadler, J. Monitoring of respiratory disease patterns in a multimicrobially infected pig population using artificial intelligence and aggregate samples. Viruses 2024, 16, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza, M.N.; Razob Ali, M.; Haque, M.A.; Jin, H.; Kyoung, H.; Choi, Y.K.; Kim, G.; Chung, S.O. A review of sound-based pig monitoring for enhanced precision production. J Anim Sci Technol. 2025, 67, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshou, D.; Chedad, A.; Van Hirtum, A.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Berckmans, D.; Ramon, H. An intelligent alarm for early detection of swine epidemics based on neural networks. Trans. ASAE 2001, 44, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, L.F.C.; Rodrigues, G.S.T.; Costa, L.B.; Kurtz, D.J.; Daros, R.R. Validation of a Swine Cough Monitoring System Under Field Conditions. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Nan, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Dai, B.; Kou, S.; Liang, C. An investigation of fusion strategies for boosting pig cough sound recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Du, B.; Dai, X.; Shen, W.; Wang, X.; Kou, S. An ensemble of deep learning frameworks applied for pig cough recognition in a complex piggery environment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkland, K.W. Characterization of Porcine Oral Fluid Specimens and Treatment Options to Improve Their Composition. M.S. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kittawornrat, A.; Panyasing, Y.; Goodell, C.; Wang, C.; Gauger, P.; Harmon, K.; Rolf, R.; Desfresne, L.; Levis, I.; Zimmerman, J. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) surveillance using pre-weaning oral fluid samples detects circulation of wild-type PRRSV. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 168, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao-Diaz, A.; Giménez-Lirola, L.; Baum, D.H.; Zimmerman, J. Guidelines for oral fluid-based surveillance of viral pathogens in swine. Porc. Health Manag. 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinou, A. An update on measurement and monitoring of cough. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 6, S728–S743. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.M.; Bacci, E.; Dicpinigaitis, P.; Vernon, M. Quantitative Measurement Properties and Score Interpretation of the Cough Severity Diary in Patients with Chronic Cough. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, G. Factors affecting the Release and Concentration of Dust in Pig Houses. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1999, 74, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Narusawa, K.; Iijima, S.; Nakayama, M.; Ishimitsu, S.; Inoue, H.; Ishida, A.; Takagi, M.; Mikami, O. Development of an early detection system for respiratory diseases in pigs. Biomed. Soft Comput. Hum. Sci. 2019, 24, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Ewen, C.L.; Trible, B.R.; Kerrigan, M.A.; Cino-Ozuna, A.G.; Samuel, M.S.; Lightner, J.E.; McLaren, D.G.; Mileham, A.J.; et al. Gene-Edited Pigs Are Protected from Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; You, S.-H.; Lee, H.-S.; Shin, Y.-K.; Cho, Y.S.; Park, T.-S.; Kang, S.-J. Sialoadhesin-dependent susceptibility and replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses in CD163-expressing cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1477540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, L.; Pijoan, C.; Dee, S.; Olin, M.; Molitor, T.; Joo, H.S.; Xiao, Z.; Murtaugh, M. Virological and immunological responses to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in a large population of gilts. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2004, 68, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chand, R.J.; Trible, B.R.; Rowland, R.R. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Laguna, J.; Salguero, F.J.; Pallarés, F.J.; Carrasco, L. Immunopathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in the respiratory tract of pigs. Vet. J. 2013, 195, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.E.; Lager, K.M.; Golde, W.; Faaberg, K.S.; Sinkora, M.; Loving, C.; Zhang, Y.I. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS): An immune dysregulatory pandemic. Immunol. Res. 2014, 59, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahe, M.C.; Dvorak, C.M.T.; Patterson, A.; Roof, M.; Murtaugh, M.P. The PRRSV-Specific Memory B Cell Response Is Long-Lived in Blood and Is Boosted during Live Virus Re-Exposure. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Salama, A.A.; Gaber, M.H.; Ali, S.A. Development and Characterization of Soy Lecithin Liposome as Potential Drug Carrier Systems for Doxorubicin. J. Pharm. Innov. 2023, 18, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.T.; Cao, V.D.; Nguyen, T.N.Q.; Le, T.T.H.; Tran, T.T.; Hoang Thi, T.T. Soy lecithin–derived liposomal delivery systems: Surface modification and current applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booher, S.L.; Cornick, N.A.; Moon, H.W. Persistence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in experimentally infected swine. Vet. Microbiol. 2002, 89, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, J.; Ballarà Rodriguez, I.; Jordà Casadevall, R.; Bruguera, S.; Llopart, D.; Barba-Vidal, E. Practical review on aetio-pathogenesis and symptoms in pigs affected by clinical and subclinical oedema disease and the use of commercial vaccines under field conditions. Animals 2025, 15, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, W.; Fratamico, P.M.; Ruth, L.E.; Bowman, A.S.; Nolting, J.M.; Manning, S.D.; Funk, J.A. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in finishing pigs: Implications on public health. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 264, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.L. The lysine decarboxylase CadA protects Escherichia coli starved of phosphate against fermentation acids. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Gu, P. Response of Escherichia coli to acid stress: Mechanisms and applications—A narrative review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, C.; Hennies, R.; Dreckmann, K.; Noguera, M.; Rathkjen, P.H.; Gassel, M.; Gereke, M. Evaluation of PRRSV-specific, maternally derived and induced immune response in Ingelvac PRRSFLEX EU vaccinated piglets in the presence of maternally transferred immunity. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, M.F.; Van Breedam, W.; De Jong, E.; Lopez Rodriguez, A.; Karniychuk, U.U.; Vanhee, M.; Van Doorsselaere, J.; Maes, D.; Nauwynck, H.J. Antibody response and maternal immunity upon boosting PRRSV-immune sows with experimental farm-specific and commercial PRRSV vaccines. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 167, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opriessnig, T.; Giménez-Lirola, L.G.; Halbur, P.G. Polymicrobial respiratory disease in pigs. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2011, 12, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, R.C.; Almond, G.; Byers, E. Swine diseases and disorders. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 5, p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, C. Porcine respiratory disease complex: Interaction of vaccination and porcine circovirus type 2, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Vet. J. 2016, 212, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Temperature (°C) | Time | Cycle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse transcription | 37 | 3 min | 1 | |

| 50 | 20 s | 1 | ||

| Pre-denaturation | 95 | 1 min | 1 | |

| PCR thermocycling | Denaturation | 95 | 5 s | 40 |

| Annealing/Extension | 56 | 30 s | ||

| Group | Mortality | Wasting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week of Study | Total (%) | Week of Study | Total (%) | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| AlimenWOW G1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 (1.2) |

| AlimenWOW G2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Control 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 13 (2.6) | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 9 (1.8) |

| Control 2 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 10 | 33 (6.6) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 (1.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoon, C.E.; Cho, D.H.; Park, H.L.; Song, J.Y.; Park, S.; Lee, S.W.; Go, Y.Y.; Choi, I.-S.; Song, C.-S.; Lee, J.-B.; et al. AI-Based Respiratory Monitoring-Guided Evaluation of Rottlerin Therapy for PRRS in Grower–Finisher Pig Farms. Viruses 2026, 18, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010072

Yoon CE, Cho DH, Park HL, Song JY, Park S, Lee SW, Go YY, Choi I-S, Song C-S, Lee J-B, et al. AI-Based Respiratory Monitoring-Guided Evaluation of Rottlerin Therapy for PRRS in Grower–Finisher Pig Farms. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Cha Eun, Dong Hyun Cho, Hye Lim Park, Ju Yeon Song, Sangshin Park, Sang Won Lee, Yun Young Go, In-Soo Choi, Chang-Seon Song, Joong-Bok Lee, and et al. 2026. "AI-Based Respiratory Monitoring-Guided Evaluation of Rottlerin Therapy for PRRS in Grower–Finisher Pig Farms" Viruses 18, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010072

APA StyleYoon, C. E., Cho, D. H., Park, H. L., Song, J. Y., Park, S., Lee, S. W., Go, Y. Y., Choi, I.-S., Song, C.-S., Lee, J.-B., Park, S.-Y., & Kang, Y.-L. (2026). AI-Based Respiratory Monitoring-Guided Evaluation of Rottlerin Therapy for PRRS in Grower–Finisher Pig Farms. Viruses, 18(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010072