Virus-like Particles and Spectral Flow Cytometry for Identification of Dengue Virus-Specific B Cells in Mice and Humans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Biotinylation and Efficiency of DENV VLPs

2.3. VLP Binding Assay to Hybridomas

2.4. Mouse Infection and Splenocyte Isolation

2.5. Flow Cytometry Staining for Mouse Splenocytes

2.6. Agglutimer Formation

2.7. Agglutimer-Binding Assays to Hybridomas

2.8. Detection of DENV-Bc in Children Using Individual VLPs and Agglutimers

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

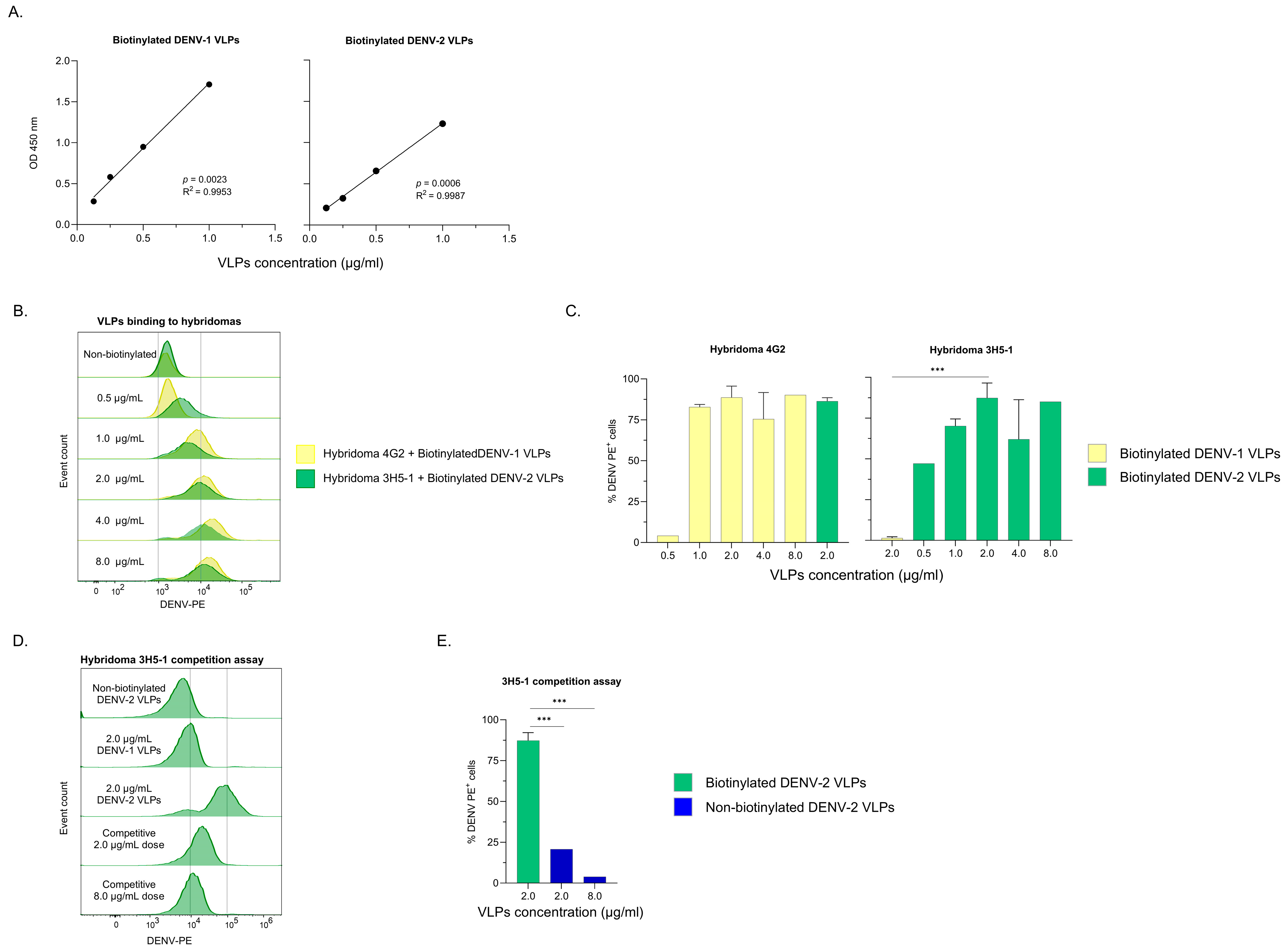

3.1. Characterization of Biotinylated VLPs

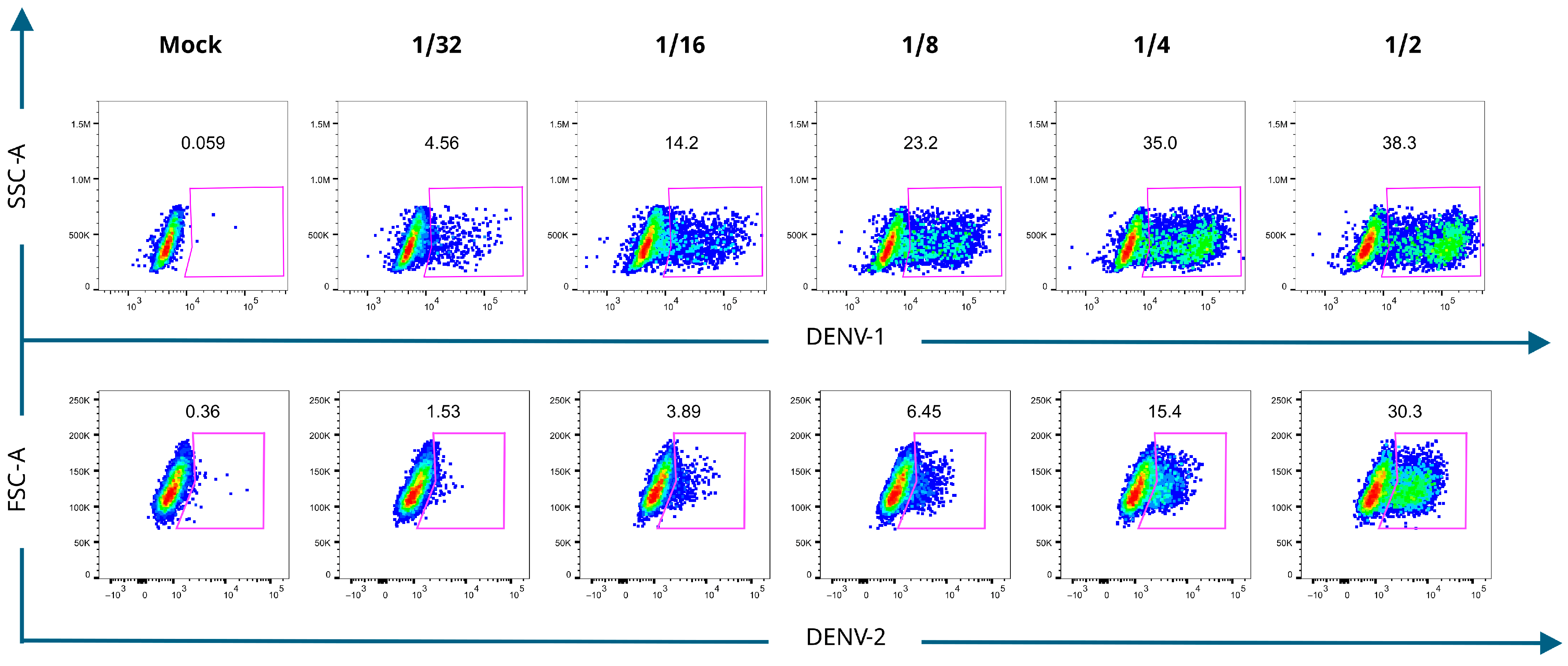

3.2. Detection of DENV-Bc in Mouse Splenocytes with VLPs

3.3. Binding of Agglutimers to Hybridomas

3.4. Detection of DENV-Bc in Hospitalized Children with Dengue

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| Bc | B cells |

| DENV-Bc | DENV-specific Bc |

| VLPs | Virus-like particles |

| E | Envelope |

| Pr-M | Pre-membrane |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| DWS | Dengue warning signs |

| SD | Severe dengue |

| PB | Plasmablasts |

| mBc | Memory Bc |

Appendix A

References

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Adams, L.E.; Deen, J.; Anderson, K.B.; Katzelnick, L.C. Dengue. Lancet 2024, 403, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A.; Singhal, R.; Pareek, A.; Chuturgoon, A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. The Unprecedented Surge of Dengue in the Americas: Strategies for Effective Response. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyamvada, L.; Cho, A.; Onlamoon, N.; Zheng, N.-Y.; Huang, M.; Kovalenkov, Y.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Angkasekwinai, N.; Pattanapanyasat, K.; Ahmed, R.; et al. B Cell Responses during Secondary Dengue Virus Infection Are Dominated by Highly Cross-Reactive, Memory-Derived Plasmablasts. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5574–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.; Dhama, N.; Gupta, R.D. Dengue Virus Neutralizing Antibody: A Review of Targets, Cross-Reactivity, and Antibody-Dependent Enhancement. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1200195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengue, P.; Aggarwal, C.; Saini, K.; Reddy, S.; Singla, M.; Nayak, K.; Chawla, Y.M. Immunophenotyping and Transcriptional Profiling of Human Plasmablasts in Dengue. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bournazos, S.; Vo, H.T.M.; Duong, V.; Auerswald, H.; Ly, S.; Sakuntabhai, A.; Dussart, P.; Cantaert, T.; Ravetch, J. V Antibody Fucosylation Predicts Disease Severity in Secondary Dengue Infection. Science 2021, 372, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, S.; Graber, A.L.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Duarte, E.M.; Zambrana, J.V.; Salinas, J.A.R.; Mercado-Hernandez, R.; Singh, T.; Katzelnick, L.C.; de Silva, A.; et al. Protection against Symptomatic Dengue Infection by Neutralizing Antibodies Varies by Infection History and Infecting Serotype. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouers, A.; Chng, M.H.Y.; Lee, B.; Rajapakse, M.P.; Kaur, K.; Toh, Y.X.; Sathiakumar, D.; Loy, T.; Thein, T.-L.; Lim, V.W.X.; et al. Immune Cell Phenotypes Associated with Disease Severity and Long-Term Neutralizing Antibody Titers after Natural Dengue Virus Infection. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrammert, J.; Onlamoon, N.; Akondy, R.S.; Perng, G.C.; Polsrila, K.; Chandele, A.; Kwissa, M.; Pulendran, B.; Wilson, P.C.; Wittawatmongkol, O.; et al. Rapid and Massive Virus-Specific Plasmablast Responses during Acute Dengue Virus Infection in Humans. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2911–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Yu, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Qiu, L. Responses of CD27+CD38+ Plasmablasts, and CD24hiCD27hi and CD24hiCD38hi Regulatory B Cells during Primary Dengue Virus 2 Infection. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e24035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.F.; Salgado, D.M.; Vega, R.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Rodríguez, L.S.; Angel, J.; Franco, M.A.; Greenberg, H.B.; Narváez, C.F. Total and Envelope Protein-Specific Antibody-Secreting Cell Response in Pediatric Dengue Is Highly Modulated by Age and Subsequent Infections. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bates, T.M.; Cordeiro, M.T.; Nascimento, E.J.M.; Smith, A.P.; Soares de Melo, K.M.; McBurney, S.P.; Evans, J.D.; Marques, E.T.A.; Barratt-Boyes, S.M. Association between Magnitude of the Virus-Specific Plasmablast Response and Disease Severity in Dengue Patients. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, A.; West, K.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Gibbons, R.V.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Green, S.; Libraty, D.; Jaiswal, S.; Rothman, A.L. B-Cell Responses During Primary and Secondary Dengue Virus Infections in Humans. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, P.; Narvekar, P.; Montoya, M.; Michlmayr, D.; Balmaseda, A.; Coloma, J.; Harris, E. Primary and Secondary Dengue Virus Infections Elicit Similar Memory B-Cell Responses, but Breadth to Other Serotypes and Cross-Reactivity to Zika Virus Is Higher in Secondary Dengue. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zompi, S.; Montoya, M.; Pohl, M.O.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Dominant Cross-Reactive B Cell Response during Secondary Acute Dengue Virus Infection in Humans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, P.; Rosa, A.; Caldeira-arau, H.; Viga, A.M.; Ebenezer, S. Mouse Models as a Tool to Study Asymptomatic DENV Infections. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1554090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuya, W.; Yuansong, Y.; Susu, L.; Chen, L.; Yong, W.; Yining, W.; YouChun, W.; Changfa, F. Progress and Challenges in Development of Animal Models for Dengue Virus Infection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2404159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.L.; Zompi, S.; Beatty, P.R.; Harris, E. A Mouse Model for Studying Dengue Virus Pathogenesis and Immune Response. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1171, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, R.M.; Prestwood, T.R.; Shresta, S. Enhanced Infection of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in a Mouse Model of Antibody-Induced Severe Dengue Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.K.W.; Zhang, S.L.; Tan, H.C.; Yan, B.; Maria Martinez Gomez, J.; Tan, W.Y.; Lam, J.H.; Tan, G.K.X.; Ooi, E.E.; Alonso, S. First Experimental In Vivo Model of Enhanced Dengue Disease Severity through Maternally Acquired Heterotypic Dengue Antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L.B.; Batalle, J.P.; Byrne, A.B.; Brahamian, J.M.; Ferretti, A.; García, A.G.; Mauri, A.; Simonetto, C.; Hijano, D.R.; Lawrence, A.; et al. The Role of Heterotypic DENV-Specific CD8 + T Lymphocytes in an Immunocompetent Mouse Model of Secondary Dengue Virus Infection. eBioMedicine 2017, 20, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.W.; Thomas, A.; White, L.; Stoops, M.; Corten, M.; Hannemann, H.; De Silva, A.M. Dengue Virus-like Particles Mimic the Antigenic Properties of the Infectious Dengue Virus Envelope. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngman, K.R.; Franco, M.A.; Kuklin, N.A.; Rott, L.S.; Butcher, E.C.; Greenberg, H.B. Correlation of Tissue Distribution, Developmental Phenotype, and Intestinal Homing Receptor Expression of Antigen-Specific B Cells During the Murine Anti-Rotavirus Immune Response. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkamp, J.H.; Kallewaard, N.; Kusuhara, K.; Feigelstock, D.; Feng, N.; Greenberg, H.B.; Crowe, J.E. Generation of Recombinant Human Monoclonal Antibodies to Rotavirus from Single Antigen-Specific B Cells Selected with Fluorescent Virus-like Particles. J. Immunol. Methods 2003, 275, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Hua, Z.; Liu, C.; Lin, L.; Chen, R.; Hou, B. Characterization of T-Dependent and T-Independent B Cell Responses to a Virus-like Particle. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 3846–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamin, R.; Kao, K.S.; MacDonald, M.R.; Cantaert, T.; Rice, C.M.; Ravetch, J.V.; Bournazos, S. Human FcγRIIIa Activation on Splenic Macrophages Drives Dengue Pathogenesis in Mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, S.L.; Perilla, P.M.; Salgado, D.M.; Rojas, M.C.; Narváez, C.F. Efficiency of Automated Viral RNA Purification for Pediatric Studies of Dengue and Zika in Hyperendemic Areas. J. Trop. Med. 2023, 2023, 1576481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam-Puc, J.C.; García-Cordero, J.; Calderón-Amador, J.; Donis-Maturano, L.; Cedillo-Barrón, L.; Flores-Romo, L. Germinal Center Reaction Following Cutaneous Dengue Virus Infection in Immune-Competent Mice. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; TDR. Dengue Guidelines, for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 41, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- ThermoFisher HABA Calculator. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/co/en/home/life-science/protein-biology/protein-labeling-crosslinking/biotinylation/biotin-quantitation-kits/haba-calculator.html (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Kirley, T.L.; Norman, A.B. Decreased Solubility and Increased Adsorptivity of a Biotinylated Humanized Anti-Cocaine MAb. Anal. Biochem. 2025, 696, 115690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Zhou, Y.; Olivarez, N.P.; Broadwater, A.H.; de Silva, A.M.; Crowe, J.E. Persistence of Circulating Memory B Cell Clones with Potential for Dengue Virus Disease Enhancement for Decades Following Infection. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woda, M.; Mathew, A. Fluorescently Labeled Dengue Viruses as Probes to Identify Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells by Multiparametric Flow Cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 416, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woda, M.; Friberg, H.; Currier, J.R.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Macareo, L.R.; Green, S.; Jarman, R.G.; Rothman, A.L.; Mathew, A. Dynamics of Dengue Virus (DENV)-Specific B Cells in the Response to DENV Serotype 1 Infections, Using Flow Cytometry with Labeled Virions. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.S.; Tang, A.; Chen, Z.; Horton, M.S.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.M.; Dubey, S.A.; Distefano, D.J.; Ettenger, A.; Fong, R.H.; et al. Rapid Isolation of Dengue-Neutralizing Antibodies from Single Cell-Sorted Human Antigen-Specific Memory B-Cell Cultures. MAbs 2016, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, S.; Bohaud, C.; Sorn, S.; Ken, S.; Rey, F.A.; Ariën, K.K.; Ly, S.; Duong, V.; Barba-spaeth, G.; Auerswald, H.; et al. Toward a Deeper Understanding of Dengue: Novel Method for Quantification and Isolation of Envelope Protein Epitope Specific Antibodies. mSphere 2025, 10, e0096124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EZ-LinkTM Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotinylation Kit. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/21435 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Tsuji, I.; Dominguez, D.; Egan, M.A.; Dean, H.J. Development of a Novel Assay to Assess the Avidity of Dengue Virus-Specific Antibodies Elicited in Response to a Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqueda-Alfaro, R.A.; Marcial-Juárez, E.; Calderón-Amador, J.; García-Cordero, J.; Orozco-Uribe, M.; Hernández-Cázares, F.; Medina-Pérez, U.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Flores-Langarica, A.; Cedillo-Barrón, L.; et al. Robust Plasma Cell Response to Skin-Inoculated Dengue Virus in Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, M.K.; Henchal, E.A.; McCown, J.M.; Brandt, W.E.; Dalrymple, J.M. Identification of Distinct Antigenic Determinants on Dengue-2 Virus Using Monoclonal Antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1981, 31, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PAHO Situación Epidemiológica del Dengue en Las Américas. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/arbo-portal/dengue/situacion-epidemiologica-dengue (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Syeda, M.Z.; Hong, T.; Huang, C.; Huang, W.; Mu, Q. B Cell Memory: From Generation to Reactivation: A Multipronged Defense Wall against Pathogens. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dengue Naive | Dengue | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 1) | (n = 10) | |

| Female/Male (n) | 0/1 | 4/6 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 4 | 11 (0.3–17) |

| Days of symptoms onset, median (range) | 4 | 6.5 (5–10) |

| Diagnostic test, n (%) | ||

| ELISA NS1+ | 0 | 8 (80) |

| ELISA DENV-IgM+ | 0 | 8 (80) |

| ELISA DENV-IgG+ | 0 | 9 (90) |

| RT-PCR+, n (%) | 0 | 7 (70) |

| DENV-1, n (%) | - | 2 (20) |

| DENV-2, n (%) | - | 1 (10) |

| DENV-3, n (%) | - | 1 (10) |

| DENV-4, n (%) | - | 3 (30) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| DWS/SD, n (%) | - | 6 (60)/4 (40) |

| Primary/secondary DENV infection, n (%) | - | 2 (20)/8 (80) |

| Frequency (%) of PB in Bc, median (range) | 0.64 | 9.84 (3.4–32.4) |

| Laboratory tests, median (range) | ||

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3) | 22,400 | 5240 (2790–9500) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 29.8 | 44 (32.4–50.1) |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | 9.5 | 14.8 (10.4–17.42) |

| Platelets (cells, mm3) | 746,000 | 52,000 (21,000–414,000) |

| AST (U/L) | 15.2 | 174.9 (31.8–652) |

| ALT (U/L) | 23 | 121 (14.6–347) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Segura, K.; Martel, F.; Franco, M.A.; Perdomo-Celis, F.; Narváez, C.F. Virus-like Particles and Spectral Flow Cytometry for Identification of Dengue Virus-Specific B Cells in Mice and Humans. Viruses 2026, 18, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010058

Segura K, Martel F, Franco MA, Perdomo-Celis F, Narváez CF. Virus-like Particles and Spectral Flow Cytometry for Identification of Dengue Virus-Specific B Cells in Mice and Humans. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegura, Katherine, Fabiola Martel, Manuel A. Franco, Federico Perdomo-Celis, and Carlos F. Narváez. 2026. "Virus-like Particles and Spectral Flow Cytometry for Identification of Dengue Virus-Specific B Cells in Mice and Humans" Viruses 18, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010058

APA StyleSegura, K., Martel, F., Franco, M. A., Perdomo-Celis, F., & Narváez, C. F. (2026). Virus-like Particles and Spectral Flow Cytometry for Identification of Dengue Virus-Specific B Cells in Mice and Humans. Viruses, 18(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010058