Generating STEC-Specific Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages Through Tailspike Protein Chimerization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. DNA, Amino Acid, and Structural In Silico Comparisons

2.3. Phage Enumeration

2.4. Phage Engineering

2.4.1. O45-specific RBP-CBA120-3 Construction

2.4.2. O111-specific RBP-CBA120-5 Construction

2.4.3. O103-specific RBP-CBA120-6 Construction

2.4.4. O26-specific RBP-CBA120-9 Construction

2.5. Phage Stock Preparation

2.6. Phage Spot Assay

2.7. Luciferase Reporter Phage Assays

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Bacteriophage C-Termini for Chimerization

3.2. Structural Comparison of CBA120’s Tailspike Proteins to Unrelated Phage

3.3. Generation of Chimeric Ackermannviridae Tailspike Proteins

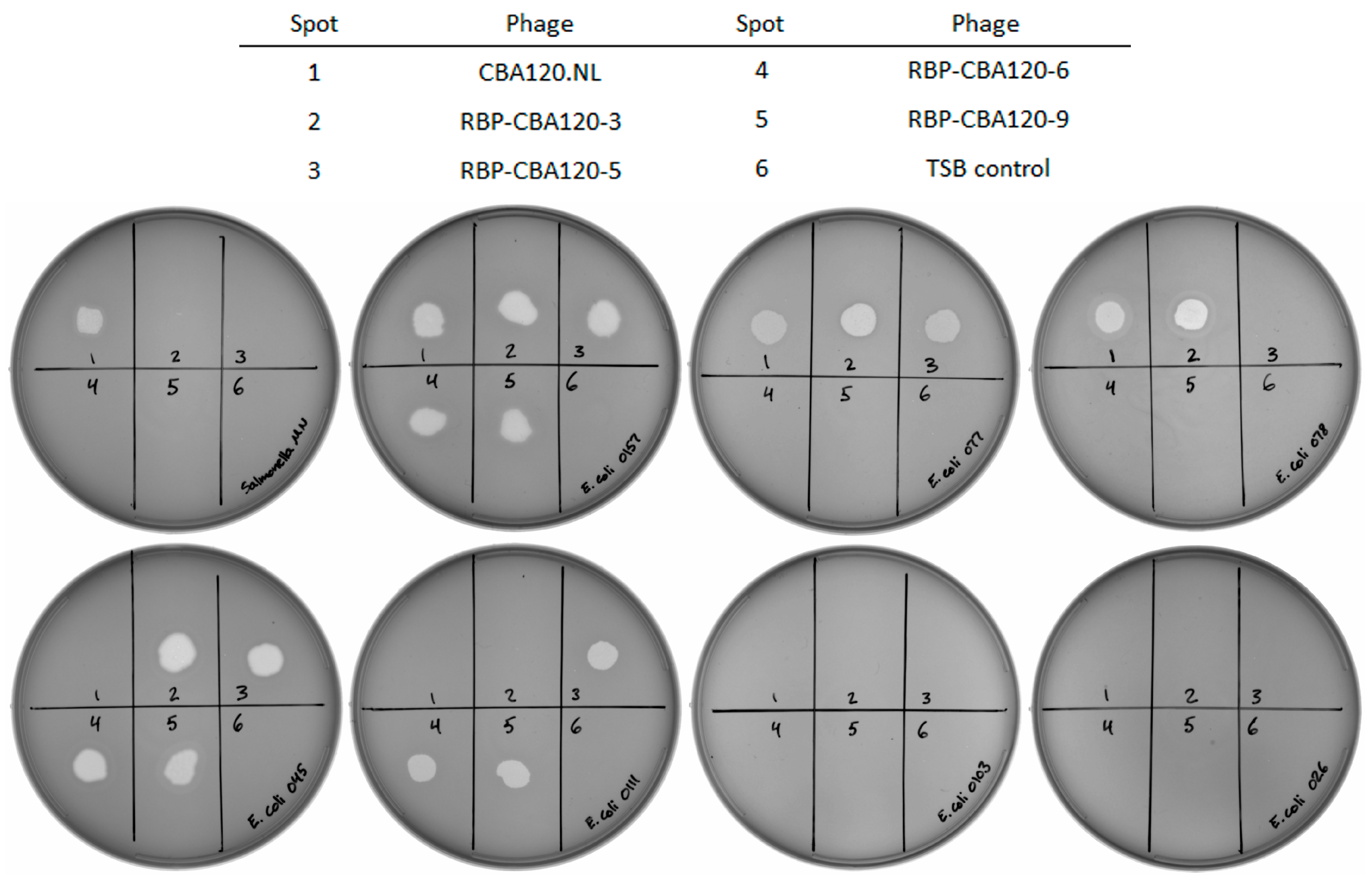

3.4. Chimeric Phage Viability on Target Bacterial Strains

3.5. Altering Host Range Detection with Chimeric Tailspike Proteins

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alharbi, M.G.; Al-Hindi, R.R.; Esmael, A.; Alotibi, I.A.; Azhari, S.A.; Alseghayer, M.S.; Teklemariam, A.D. The “Big Six”: Hidden Emerging Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, S.; Hoffmann, S.; White, A.; Ahn, J.-W.; McQueen, R.B.; Scallan Walter, E. Cost of Hospitalizations for Leading Foodborne Pathogens in the United States: Identification by International Classification of Disease Coding and Variation by Pathogen. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2021, 18, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, Y.; Gilmour, S.; Ota, E.; Momose, Y.; Onishi, T.; Bilano, V.L.F.; Kasuga, F.; Sekizaki, T.; Shibuya, K. Estimating the Burden of Foodborne Diseases in Japan. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacioglu, O.; Sharma, M.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Goktepe, I. Biocontrol of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on Fresh-Cut Leafy Greens. Bacteriophage 2013, 3, e24620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristobal-Cueto, P.; García-Quintanilla, A.; Esteban, J.; García-Quintanilla, M. Phages in Food Industry Biocontrol and Bioremediation. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisuthiphaet, N.; Yang, X.; Young, G.M.; Nitin, N. Rapid Detection of Escherichia coli in Beverages Using Genetically Engineered Bacteriophage T7. AMB Express 2019, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.J.; Rudolf, M.; Scherer, S. Evaluation of Luciferase Reporter Bacteriophage A511::LuxAB for Detection of Listeria monocytogenes in Contaminated Foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2961–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.M.; Gil, J.; Brown, M.; Cesar Tondo, E.; Soraya Martins De Aquino, N.; Eisenberg, M.; Erickson, S. Accurate and Sensitive Detection of Salmonella in Foods by Engineered Bacteriophages. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, S.A.A.; Limoges, R.G.; El-Cheikh, H. Bacteriophage Biocontrol in Wastewater Treatment. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.A.; Houjeiry, S.E.; Kanj, S.S.; Matar, G.M.; Saba, E.S. From Forgotten Cure to Modern Medicine: The Resurgence of Bacteriophage Therapy. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 39, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumet, L.; Ahmad-Mansour, N.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Kissa, K.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.-P.; Costechareyre, D.; Molle, V. Bacteriophage Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Infections: A Review of Animal Models, Treatments, and Clinical Trials. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 907314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Ford, K.; Harris, K.; Gilmour, K.C.; Soothill, J.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Schooley, R.T.; et al. Engineered Bacteriophages for Treatment of a Patient with a Disseminated Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo Altamirano, F.L.; Barr, J.J. Phage Therapy in the Postantibiotic Era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00066-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Paulson, J.; Brown, M.; Zahn, H.; Nguyen, M.M.; Eisenberg, M.; Erickson, S. Tailoring the Host Range of Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages through Chimeric Tailspike Proteins. Viruses 2023, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, S.; Paulson, J.; Brown, M.; Hahn, W.; Gil, J.; Barron-Montenegro, R.; Moreno-Switt, A.I.; Eisenberg, M.; Nguyen, M.M. Isolation and Engineering of a Listeria grayi Bacteriophage. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.P.; Unch, J.; Binkowski, B.F.; Valley, M.P.; Butler, B.L.; Wood, M.G.; Otto, P.; Zimmerman, K.; Vidugiris, G.; Machleidt, T.; et al. Engineered Luciferase Reporter from a Deep Sea Shrimp Utilizing a Novel Imidazopyrazinone Substrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A.N.; Brøndsted, L. Renewed Insights into Ackermannviridae Phage Biology and Applications. npj Viruses 2024, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, S.; Baxa, U.; Miller, S.; Weintraub, A.; Seckler, R.; Huber, R. Crystal Structure of Phage P22 Tailspike Protein Complexed with Salmonella sp. O-Antigen Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 10584–10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Lemire, S.; Pires, D.P.; Lu, T.K. Engineering Modular Viral Scaffolds for Targeted Bacterial Population Editing. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Lo, Y.-H.; Tseng, P.-W.; Chang, S.-F.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, T.-S. A T3 and T7 Recombinant Phage Acquires Efficient Adsorption and a Broader Host Range. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouillot, F.; Blois, H.; Iris, F. Genetically Engineered Virulent Phage Banks in the Detection and Control of Emergent Pathogenic Bacteria. Biosecur. Bioterror. Biodef. Strat. Pract. Sci. 2010, 8, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, A.N.; Woudstra, C.; Sørensen, M.C.H.; Brøndsted, L. Subtypes of Tail Spike Proteins Predicts the Host Range of Ackermannviridae Phages. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4854–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, E.M.; Skutt-Kakaria, K.; Blasdel, B.; El-Shibiny, A.; Castano, A.; Bryan, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Villegas, A.; Ackermann, H.-W.; Toribio, A.L.; et al. Characterization of a ViI-like Phage Specific to Escherichia coli O157:H7. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, C.; Fratamico, P.M.; Yan, X.; Baranzoni, G.; Liu, Y.; Needleman, D.S.; Tebbs, R.; O’Connell, C.D.; Allred, A.; Swimley, M.; et al. Comparison of O-Antigen Gene Clusters of All O-Serogroups of Escherichia coli and Proposal for Adopting a New Nomenclature for O-Typing. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, M.; Shneider, M.M.; Arbatsky, N.P.; Shashkov, A.S.; Chizhov, A.O.; Nazarov, S.; Prokhorov, N.S.; Taylor, N.M.I.; Buth, S.A.; Gambino, M.; et al. Structure and Function of the Branched Receptor-Binding Complex of Bacteriophage CBA120. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3718–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D20–D29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pas, C.; Latka, A.; Fieseler, L.; Briers, Y. Phage Tailspike Modularity and Horizontal Gene Transfer Reveals Specificity towards E. coli O-Antigen Serogroups. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Ding, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Genomic Characterization of a Novel Bacteriophage STP55 Revealed Its Prominent Capacity in Disrupting the Dual-Species Biofilm Formed by Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli O157: H7 Strains. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-T.; Liu, F.; Wu, V.C.H. Complete Genome Sequence of a Lytic T7-Like Phage, Escherichia Phage VB_EcoP-Ro45lw, Isolated from Nonfecal Compost Samples. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8, e00036-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liao, Y.-T.; Zhang, Y.; Salvador, A.; Ho, K.-J.; Wu, V.C.H. A New Kayfunavirus-like Escherichia Phage VB_EcoP-Ro45lw with Antimicrobial Potential of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O45 Strain. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.-T.; Salvador, A.; Lavenburg, V.M.; Wu, V.C.H. Characterization of Two New Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O103-Infecting Phages Isolated from an Organic Farm. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, P.; Longden, I.; Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000, 16, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, S.B.; Wunsch, C.D. A General Method Applicable to the Search for Similarities in the Amino Acid Sequence of Two Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1970, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Bales, P.; Greenfield, J.; Heselpoth, R.D.; Nelson, D.C.; Herzberg, O. Crystal Structure of ORF210 from E. coli O157:H1 Phage CBA120 (TSP1), a Putative Tailspike Protein. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, J.; Shang, X.; Luo, H.; Zhou, Y.; Heselpoth, R.D.; Nelson, D.C.; Herzberg, O. Structure and Tailspike Glycosidase Machinery of ORF212 from E. coli O157:H7 Phage CBA120 (TSP3). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K.L.; Shang, X.; Greenfield, J.; Linden, S.B.; Alreja, A.B.; Nelson, D.C.; Herzberg, O. Structure of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Bacteriophage CBA120 Tailspike Protein 4 Baseplate Anchor and Tailspike Assembly Domains (TSP4-N). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittrich, S.; Segura, J.; Duarte, J.M.; Burley, S.K.; Rose, Y. RCSB Protein Data Bank: Exploring Protein 3D Similarities via Comprehensive Structural Alignments. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.W.; Jorgensen, E.M. ApE, A Plasmid Editor: A Freely Available DNA Manipulation and Visualization Program. Front. Bioinforma. 2022, 2, 818619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärber, G. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1931, 162, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Yang, J.; Hu, J.; Sun, X. On the Calculation of TCID50 for Quantitation of Virus Infectivity. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latka, A.; Lemire, S.; Grimon, D.; Dams, D.; Maciejewska, B.; Lu, T.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Briers, Y. Engineering the Modular Receptor-Binding Proteins of Klebsiella Phages Switches Their Capsule Serotype Specificity. mBio 2021, 12, e00455–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, J.; Shang, X.; Luo, H.; Zhou, Y.; Linden, S.B.; Heselpoth, R.D.; Leiman, P.G.; Nelson, D.C.; Herzberg, O. Structure and Function of Bacteriophage CBA120 ORF211 (TSP2), the Determinant of Phage Specificity towards E. coli O157:H7. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutter, E. Phage Host Range and Efficiency of Plating. In Bacteriophages: Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 501, pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Fiedler, C.; Grassl, R.; Biebl, M.; Rachel, R.; Hermo-Parrado, X.L.; Llamas-Saiz, A.L.; Seckler, R.; Miller, S.; Van Raaij, M.J. Structure of the Receptor-Binding Protein of Bacteriophage Det7: A Podoviral Tail Spike in a Myovirus. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2265–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Paulson, J.; Zahn, H.; Brown, M.; Nguyen, M.M.; Erickson, S. Development of a Replication-Deficient Bacteriophage Reporter Lacking an Essential Baseplate Wedge Subunit. Viruses 2024, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Origin of Tailspike C-Terminus | Bacterial Species and Serogroups Targeted by TSP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage | TSP1 | TSP2 | TSP3 | TSP4 | TSP1 | TSP2 | TSP3 | TSP4 |

| CBA120.NL | CBA120 | CBA120 | CBA120 | CBA120 | S. enterica O:21 | E. coli O157 | E. coli O77 | E. coli O78 |

| RBP-CBA120-3 | Ro45lw | CBA120 | CBA120 | CBA120 | E. coli O45 | E. coli O157 | E. coli O77 | E. coli O78 |

| RBP-CBA120-5 | Ro45lw | CBA120 | CBA120 | STP55 | E. coli O45 | E. coli O157 | E. coli O77 | E. coli O111 |

| RBP-CBA120-6 | Ro45lw | CBA120 | Ro103C3Iw | STP55 | E. coli O45 | E. coli O157 | E. coli O103 | E. coli O111 |

| RBP-CBA120-9 | Ro45lw | CBA120 | RM10386 | STP55 | E. coli O45 | E. coli O157 | E. coli O26 | E. coli O111 |

| TSP/Accession | CBA120.TSP1 | CBA120.TSP2 | CBA120.TSP3 | CBA120.TSP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STP55.TSP4 UPU15645.1 | 18.0% | 15.8% | 18.8% | 50.8% |

| Ro45lw.TSP YP_009818296.1 | 15.5% | 15.2% | 17.5% | 11.6% |

| Ro103C3Iw.TSP QDH94159.1 | 18.6% | 14.6% | 20.9% | 14.7% |

| RM10386.TSP WP_038987731.1 | 16.7% | 13.6% | 13.7% | 13.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil, J.; Paulson, J.; Zahn, H.; Brown, M.; Nguyen, M.M.; Erickson, S. Generating STEC-Specific Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages Through Tailspike Protein Chimerization. Viruses 2025, 17, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121614

Gil J, Paulson J, Zahn H, Brown M, Nguyen MM, Erickson S. Generating STEC-Specific Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages Through Tailspike Protein Chimerization. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121614

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil, Jose, John Paulson, Henriett Zahn, Matthew Brown, Minh M. Nguyen, and Stephen Erickson. 2025. "Generating STEC-Specific Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages Through Tailspike Protein Chimerization" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121614

APA StyleGil, J., Paulson, J., Zahn, H., Brown, M., Nguyen, M. M., & Erickson, S. (2025). Generating STEC-Specific Ackermannviridae Bacteriophages Through Tailspike Protein Chimerization. Viruses, 17(12), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121614