Timely Association of RSV Hospitalisation Waves in Children with the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the General Population in Eastern Bavaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

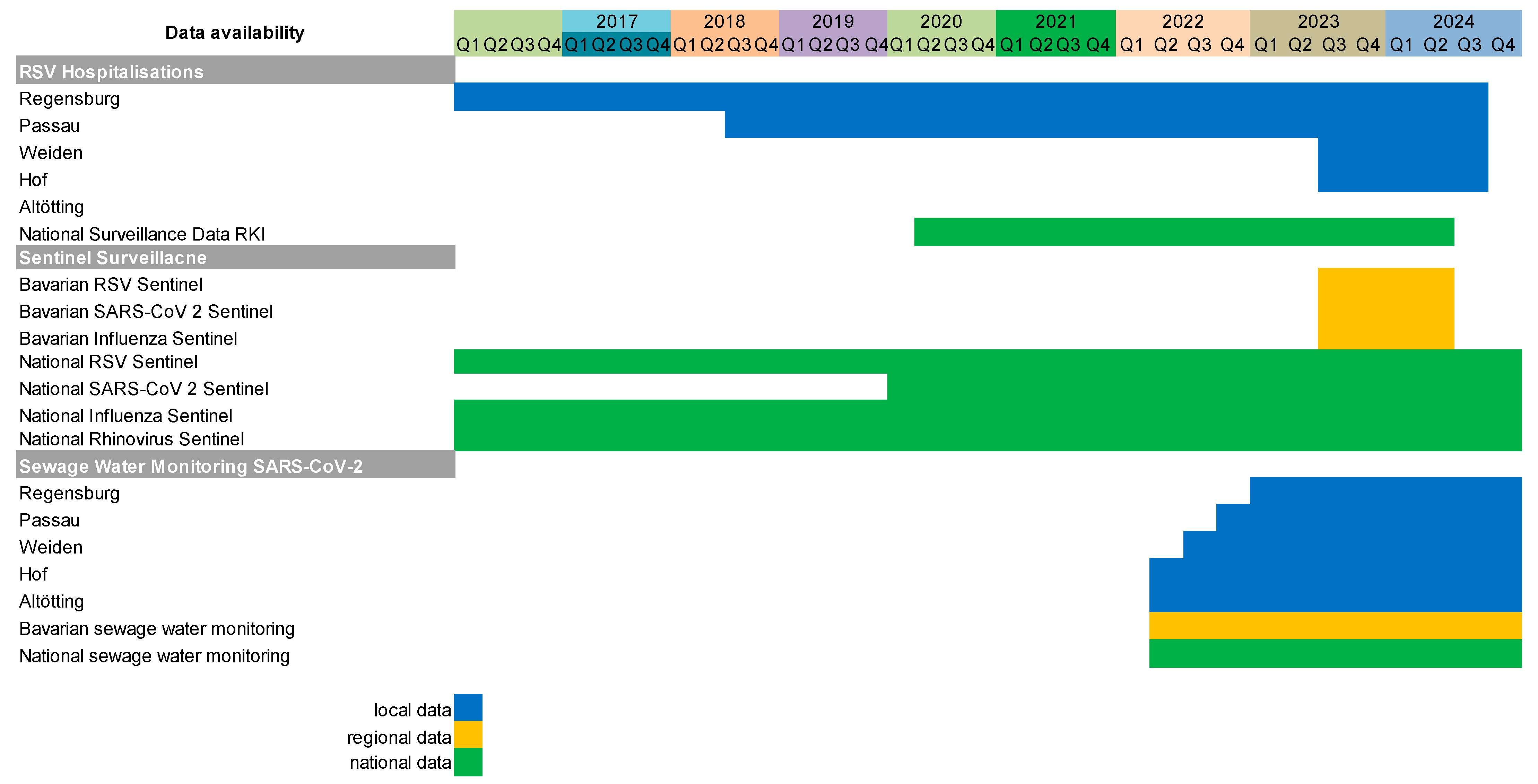

2. Materials and Methods

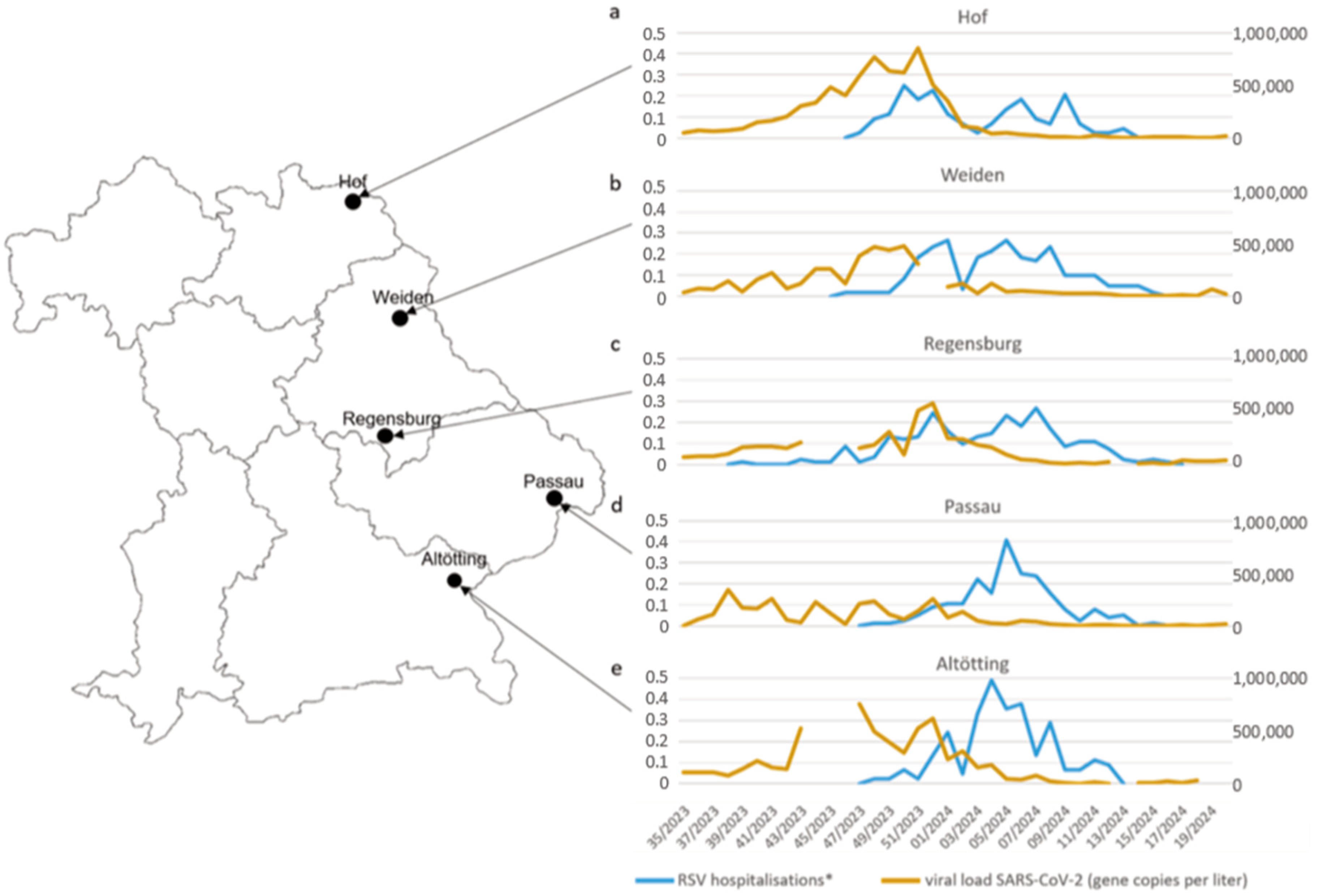

2.1. Local RSV Hospitalisation Data

2.2. Regional Bavarian RSV and SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance Data

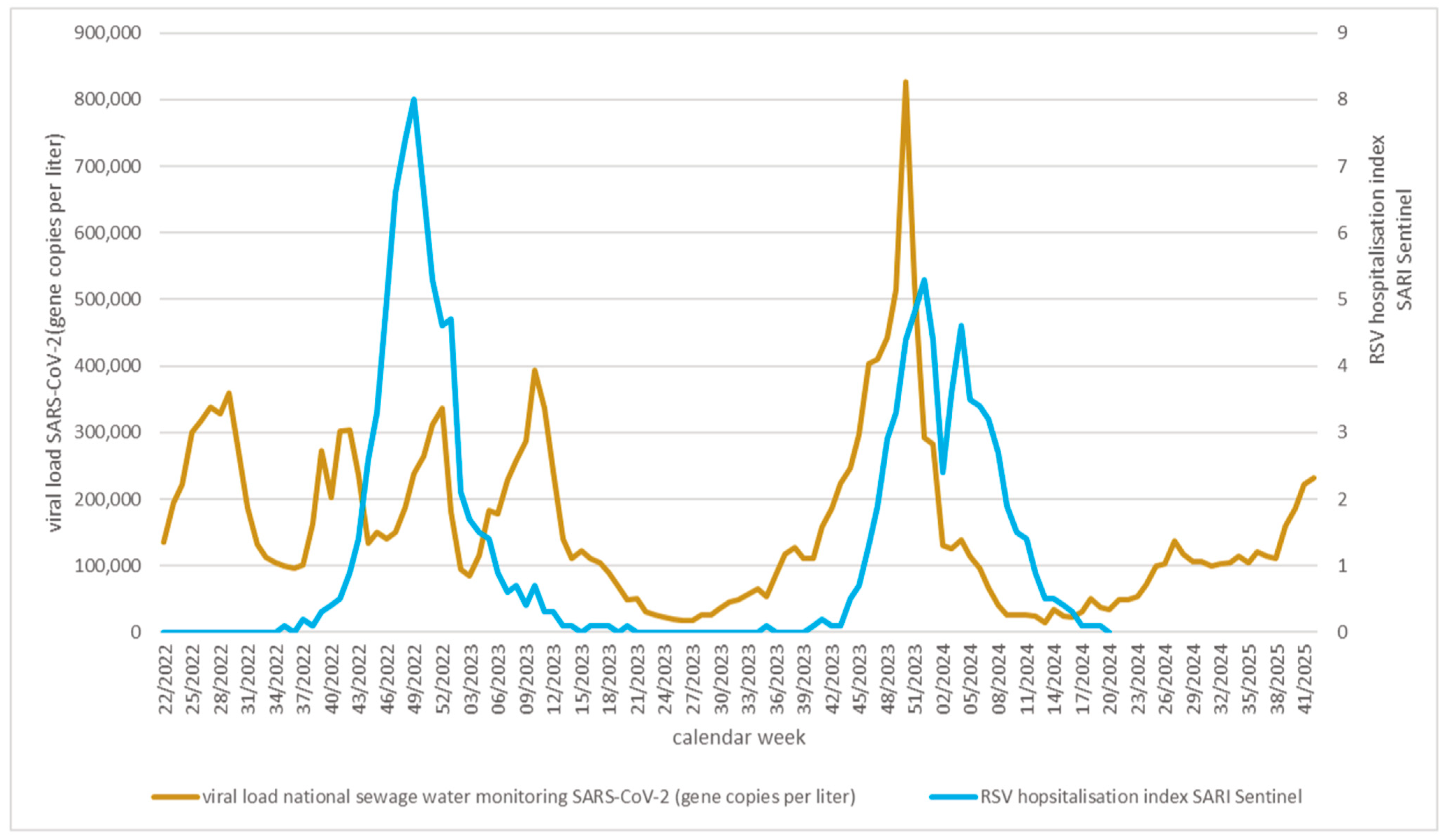

2.3. National German RSV and SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance Data

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fleming, D.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Cross, K.W. Morbidity profiles of patients consulting during influenza and respiratory syncytial virus active periods. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007, 135, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.B.; Weinberg, G.A.; Iwane, M.K.; Blumkin, A.K.; Edwards, K.M.; Staat, M.A.; Auinger, P.; Griffin, M.R.; Poehling, K.A.; Erdman, D.; et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Chu, Y.; Perin, J.; Zhu, J.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2016, 388, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garegnani, L.; Styrmisdóttir, L.; Roson Rodriguez, P.; Escobar Liquitay, C.M.; Esteban, I.; Franco, J.V. Palivizumab for preventing severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD013757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosch, A.; Luber, D.; Klawonn, F.; Kabesch, M. Focusing on severe infections with the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in adults: Risk factors, symptomatology and clinical course compared to influenza A/B and the original SARS-CoV-2 strain. J. Clin. Virol. 2023, 161, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, A.; Pemmerl, S.; Kabesch, M.; Ambrosch, A. Comparative analysis of RSV-related hospitalisations in children and adults over a 7 year-period before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Virol. 2023, 166, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Respiratory Virus Surveillance Summary. Available online: https://erviss.org/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Griffiths, C.; Drews, S.J.; Marchant, D.J. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Infection, Detection, and New Options for Prevention and Treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, A.; Kabesch, M.; Ambrosch, A. The Frequency of Hospitalizations for RSV and Influenza Among Children and Adults. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiroddin, P.; Gaertner, V.D.; Schöberl, P.; Fischer, E.; Niggel, J.; Pagel, P.; Lampl, B.M.J.; Ambrosch, A.; Kabesch, M. Gargle pool PCR testing in a hospital during medium and high SARS-CoV-2 incidence. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 127, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibali, E.; Wenzel, J.J.; Gruber, R.; Ambrosch, A. Pooling for SARS-CoV-2-testing: Comparison of three commercially available RT-qPCR kits in an experimental approach. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2021, 59, e243–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köse, B.; Schaumburg, F. Diagnostic accuracy of Savanna RVP4 (QuidelOrtho) for the detection of Influenza A virus, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0115324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, A.; Selvarangan, R.; Konrad, K.; Faron, M.L.; Shakir, S.M.; Hillyard, D.; McCall, R.K.; McHardy, I.H.; Goldberg, D.C.; Dunn, J.J.; et al. Multi-center clinical evaluation of the Panther Fusion SARS-CoV-2/Flu A/B/RSV assay in nasopharyngeal swab specimens from symptomatic individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0082723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIS+C: Das Bayern Influenza + Corona Sentinel. Available online: https://www.lgl.bayern.de/gesundheit/infektionsschutz/molekulare_surveillance/bis_c/bisc_ergebnisse.htm (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Lacroix, S.; Flechsler, J.; Angermeier, H.; Heinzinger, S.; Eberle, U.; Ackermann, N.; Sing, A. Molekulare Surveillance viraler ARE-Erreger im Bayern Influenza Corona Sentinel (BIS+C) Vergleich der Jahre 2021/22 und 2022/23. Bayer. Ärzteblatt 2024, 4, 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, A. SARS-CoV-2 Abwassermonitoring in Bayern-Bay-VOC. Available online: https://www.bay-voc.lmu.de/abwassermonitoring (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Robert Koch-Institute. Wastewater-Based Surveillance on SARS-CoV-2; Robert Koch-Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RKI=ARE-Praxis-Sentinel. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/Sentinel/ARE-Praxis-Sentinel/node.html (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Lange, M.; Happle, C.; Hamel, J.; Dördelmann, M.; Bangert, M.; Kramer, R.; Eberhardt, F.; Panning, M.; Heep, A.; Hansen, G.; et al. Non-Appearance of the RSV Season 2020/21 During the COVID-19 Pandemic–Prospective, Multicenter Data on the Incidence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 561–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch-Institut, Robert; Influenza, A. Wochenberichte. Available online: https://influenza.rki.de/Wochenberichte.aspx (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Tolksdorf, K.; Goerlitz, L.; Gvaladze, T.; Haas, W.; Buda, S. SARI-Hospitalisierungsinzidenz; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland; Available online: https://robert-koch-institut.github.io/SARI-Hospitalisierungsinzidenz/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Tolksdorf, K.; Haas, W.; Schuler, E.; Wieler, L.H.; Schilling, J.; Hamouda, O.; Diercke, M.; Buda, S. ICD-10 based syndromic surveillance enables robust estimation of burden of severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization and intensive care treatment. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit, Pflege und Prävention. Krankenhausplan des Freistaates Bayern; Bayerisches Staatsministeriumg für Gesundheit und Pflege: Munich, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Institut, Robert. Epidemiologische Situation der RSV-Infektionen auf Basis der Meldedaten für die erste Saison 2023/24 nach Einführung der RSV-Meldepflicht in Deutschland. 2024. Available online: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/12158 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Brown, H.M.; Hwang, S. Direct Antiviral Mechanisms of Interferon-Gamma. Immune Netw. 2018, 18, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović-Raković, N.; Whitfield, J.R. Between immunomodulation and immunotolerance: The role of IFNγ in SARS-CoV-2 disease. Cytokine 2021, 146, 155637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannattasio, A.; Maglione, M.; D’Anna, C.; Muzzica, S.; Angrisani, F.; Acierno, S.; Perrella, A.; Tipo, V. Silent RSV in infants with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case series. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 3044–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.R.; Qu, Y.; Thomason, K.S.; de Mello, A.H.; Preble, R.; Menachery, V.D.; Casola, A.; Garofalo, R.P. The impact of RSV/SARS-CoV-2 co-infection on clinical disease and viral replication: Insights from a BALB/c mouse model. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinky, L.; Dobrovolny, H.M. Epidemiological Consequences of Viral Interference: A Mathematical Modeling Study of Two Interacting Viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 830423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panatto, D.; Domnich, A.; Lai, P.L.; Ogliastro, M.; Bruzzone, B.; Galli, C.; Stefanelli, F.; Pariani, E.; Orsi, A.; Icardi, G. Epidemiology and molecular characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among italian community-dwelling adults, 2021/22 season. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares-Gómez, S.; Mallah, N.; Santiago-Pérez, M.-I.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Pérez-Martínez, O.; Otero-Barrós, M.-T.; Suárez-Gaiche, N.; Kramer, R.; Jin, J.; Platero-Alonso, L.; et al. Effectiveness and impact of universal prophylaxis with nirsevimab in infants against hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus in Galicia, Spain: Initial results of a population-based longitudinal study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | 2023/2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 224 | 152 | 326 | 166 | 0 | 244 | 334 | 219 |

| Median age (months) | 4 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 9 | |

| IQR | 13.5 | 17 | 21 | 21 | 26 | 24.25 | 23 | |

| Median duration of inpatient treatment (days) | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| IQR | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Inpatient treatment at least 7–10 days (absolute numbers and %) | 27 (12.1) | 26 (17.1) | 33 (10.1) | 16 (9.6) | 33 (13.5) | 37 (11.1) | 28 (12.8) | |

| Inpatient treatment at least 10 days (absolute numbers and %) | 16 (7.1) | 7 (4.6) | 25 (7.7) | 12 (7.2) | 20 (8.2) | 23 (6.9) | 16 (7.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiefer, A.; Ambrosch, A.; Lampl, B.M.J.; Schneble, F.; Rubarth, K.; Vlaho, S.; Keller, M.; Kabesch, M. Timely Association of RSV Hospitalisation Waves in Children with the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the General Population in Eastern Bavaria. Viruses 2025, 17, 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121584

Kiefer A, Ambrosch A, Lampl BMJ, Schneble F, Rubarth K, Vlaho S, Keller M, Kabesch M. Timely Association of RSV Hospitalisation Waves in Children with the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the General Population in Eastern Bavaria. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121584

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiefer, Alexander, Andreas Ambrosch, Benedikt M. J. Lampl, Fritz Schneble, Kai Rubarth, Stefan Vlaho, Matthias Keller, and Michael Kabesch. 2025. "Timely Association of RSV Hospitalisation Waves in Children with the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the General Population in Eastern Bavaria" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121584

APA StyleKiefer, A., Ambrosch, A., Lampl, B. M. J., Schneble, F., Rubarth, K., Vlaho, S., Keller, M., & Kabesch, M. (2025). Timely Association of RSV Hospitalisation Waves in Children with the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the General Population in Eastern Bavaria. Viruses, 17(12), 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121584