Burden and Characteristics of RSV-Associated Hospitalizations in Switzerland: A Nationwide Analysis from 2017 to 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. Statistical Methods

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

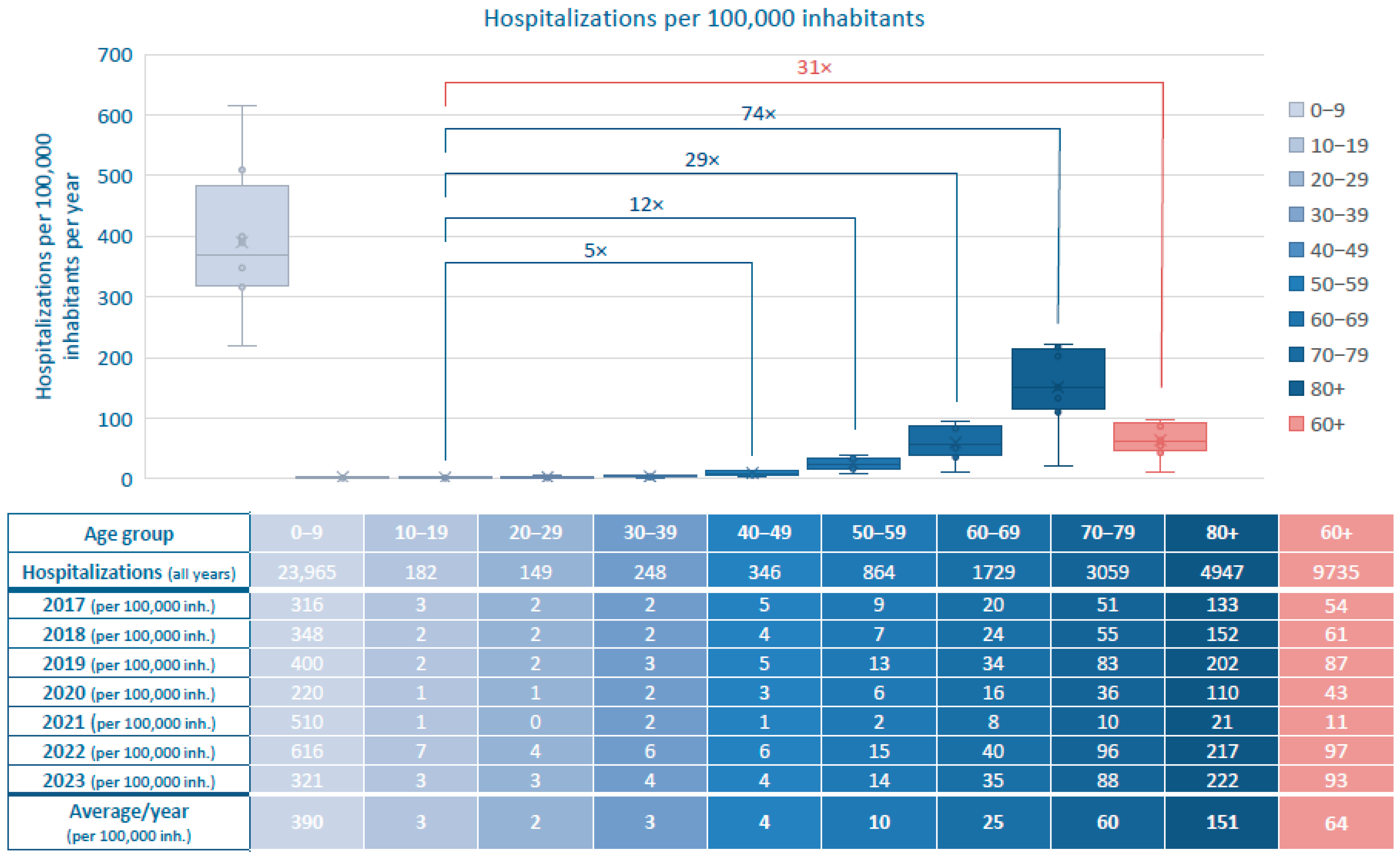

3.1. Epidemiology

3.2. Outcome

3.2.1. Length of Hospital Stay of RSV-Related Hospitalizations 2017–2023

3.2.2. RSV-Related Hospitalizations Admitted to Intensive Care Units 2017–2023

3.2.3. RSV-Related Hospitalizations Requiring Mechanical Ventilation 2017–2023

3.2.4. In-Hospital Mortality in RSV-Related Hospitalizations 2017–2023

3.3. RSV Infection as Primary vs. Secondary Diagnosis and Additionally Coded Diagnoses

3.4. Chronic Comorbidities in Patients with RSV-Related Hospitalizations

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| FOPH | Federal Office of Public Health |

| FSO | Swiss Federal Statistical Office |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| LOS | length of hospital stay |

| RSV | respiratory syncytial virus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Piralla, A.; Chen, Z.; Zaraket, H. An update on respiratory syncytial virus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, N.I.; Caballero, M.T.; Nunes, M.C. Severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in children: Burden, management, and emerging therapies. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2024, 404, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Riccio, M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Osei-Yeboah, R.; Johannesen, C.K.; Fernandez, L.V.; Teirlinck, A.C.; Wang, X.; Heikkinen, T.; Bangert, M.; Caini, S.; et al. Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the European Union: Estimation of RSV-associated hospitalizations in children under 5 years. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Blau, D.M.; Caballero, M.T.; Feikin, D.R.; Gill, C.J.; Madhi, S.A.; Omer, S.B.; Simões, E.A.F.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 2047–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, R.M.; van Wijhe, M.; Tong, S.; Lehtonen, T.; Stona, L.; Teirlinck, A.C.; Fernandez, L.V.; Li, Y.; Giaquinto, C.; Fischer, T.K.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospital Admissions in Children Younger Than 5 Years in 7 European Countries Using Routinely Collected Datasets. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222 (Suppl. 7), S599–S605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estofolete, C.F.; Banho, C.A.; Verro, A.T.; Gandolfi, F.A.; dos Santos, B.F.; Sacchetto, L.; Marques, B.d.C.; Vasilakis, N.; Nogueira, M.L. Clinical Characterization of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Adults: A Neglected Disease? Viruses 2023, 15, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Van-Tam, J.S.; O’Leary, M.; Martin, E.T.; Heijnen, E.; Callendret, B.; Fleischhackl, R.; Comeaux, C.; Tran, T.M.P.; Weber, K. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in older and high-risk adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence from developed countries. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Yeboah, R.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Del Riccio, M.; Fischer, T.K.; Egeskov-Cavling, A.M.; Bøås, H.; van Boven, M.; Wang, X.; Lehtonen, T.; Bangert, M.; et al. Estimation of the Number of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalizations in Adults in the European Union. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Strategy for Global Respiratory Syncytial Virus Surveillance Project Based on the Influenza Platform. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-strategy-for-global-respiratory-syncytial-virus-surveillance-project-based-on-the-influenza-platform (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Presser, L.D.; van den Akker, W.M.R.; Meijer, A. PROMISE Investigators Respiratory Syncytial Virus European Laboratory Network 2022 Survey: Need for Harmonization and Enhanced Molecular Surveillance. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, S34–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hammerstein, A.L.; Aebi, C.; Barbey, F.; Berger, C.; Buettcher, M.; Casaulta, C.; Egli, A.; Gebauer, M.; Guerra, B.; Kahlert, C.; et al. Interseasonal RSV infections in Switzerland—Rapid establishment of a clinician-led national reporting system (RSV EpiCH). Swiss. Med. Wkly. 2021, 151, w30057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.M.; Khan, F.; Begier, E.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Jodar, L.; Falsey, A.R. Rates of Medically Attended RSV Among US Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kulkarni, D.; Begier, E.; Wahi-Singh, P.; Wahi-Singh, B.; Gessner, B.; Nair, H. Adjusting for Case Under-Ascertainment in Estimating RSV Hospitalisation Burden of Older Adults in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Modelling Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Warren, J.L.; Shapiro, E.D.; Pitzer, V.E.; Weinberger, D.M. Estimated incidence of respiratory hospitalizations attributable to RSV infections across age and socioeconomic groups. Pneumonia 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeskov-Cavling, A.M.; Johannesen, C.K.; Lindegaard, B.; Fischer, T.K. PROMISE Investigators Underreporting and Misclassification of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Coded Hospitalization Among Adults in Denmark Between 2015–2016 and 2017–2018. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229 (Suppl. 1), S78–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuchekwa, C.; Moreo, L.M.; Menon, S.; Machado, B.; Curcio, D.; Kalina, W.; Atwell, J.E.; Gessner, B.D.; Siapka, M.; Agarwal, N.; et al. Underascertainment of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Adults Due to Diagnostic Testing Limitations: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begier, E.; Aliabadi, N.; Ramirez, J.A.; McGeer, A.; Liu, Q.; Carrico, R.; Mubareka, S.; Uppal, S.; Furmanek, S.; Zhong, Z.; et al. Detection by Nasopharyngeal Swabs Alone Underestimates Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Related Hospitalization Incidence in Adults: The Multispecimen Study’s Final Analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 232, e126–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marot, S.; Demont, C.; Cocherie, T.; Jiang, M.; Charpentier, C.; Araujo, A.; Lu, T.; Uhart, M.; El Mouaddin, N.; Lemaitre, M.; et al. Incidence and Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalizations Among People 65 and Older in France: A National Hospital Database Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munywoki, P.K.; Koech, D.C.; Agoti, C.N.; Kibirige, N.; Kipkoech, J.; Cane, P.A.; Medley, G.F.; Nokes, D.J. Influence of age, severity of infection, and co-infection on the duration of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) shedding. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). Diagnostic Testing for RSV. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/hcp/clinical-overview/diagnostic-testing.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Begley, K.M.; Leis, A.M.; Petrie, J.G.; Truscon, R.; Johnson, E.; Lamerato, L.E.; Wei, M.; Monto, A.S.; Martin, E.T. Epidemiology of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Adults and Children with Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness Over Three Seasons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzis, O.; Darbre, S.; Pasquier, J.; Meylan, P.; Manuel, O.; Aubert, J.D.; Beck-Popovic, M.; Masouridi-Levrat, S.; Ansari, M.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Burden of severe RSV disease among immunocompromised children and adults: A 10 year retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.; Widmer, A.F.; Decker, M.; Steffen, I.; Halter, J.; Heim, D.; Weisser, M.; Gratwohl, A.; Fluckiger, U.; Hirsch, H.H. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with hematological diseases: Single-center study and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, K.S.; Edwards, K.M.; Talbot, H.K. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Associations With Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.M.A.; Donaldson, G.C.; Johnston, S.L.; Openshaw, P.J.M.; Wedzicha, J.A. Respiratory syncytial virus, airway inflammation, and FEV1 decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, D.J.; Thwaites, R.S.; Ritchie, A.I.; Finney, L.; Macleod, M.; Kamal, F.; Shahbakhti, H.; van Smoorenburg, L.H.; Kerstjens, H.A.M.; Wildenbeest, J.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus-related Community Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations and Novel Diagnostics: A Binational Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MonAM—Schweizer Monitoring-System Sucht und nichtübertragbare Krankheiten|FOPH. Available online: https://ind.obsan.admin.ch/en/monam (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Stucki, M.; Lenzin, G.; Agyeman, P.K.; Posfay-Barbe, K.M.; Ritz, N.; Trück, J.; Fallegger, A.; Oberle, S.G.; Martyn, O.; Wieser, S. Inpatient burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in Switzerland, 2003 to 2021: An analysis of administrative data. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demografische Bilanz Nach Alter. Available online: http://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/de/px-x-0102020000_103/px-x-0102020000_103/px-x-0102020000_103.px/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ison, M.G.; Papi, A.; Athan, E.; Feldman, R.G.; Langley, J.M.; Lee, D.-G.; Leroux-Roels, I.; Martinon-Torres, F.; Schwarz, T.F.; van Zyl-Smit, R.N.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Prefusion F Protein Vaccine (RSVPreF3 OA) in Older Adults Over 2 RSV Seasons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 1732–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosch, A.; Luber, D.; Klawonn, F.; Kabesch, M. Focusing on severe infections with the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in adults: Risk factors, symptomatology and clinical course compared to influenza A / B and the original SARS-CoV-2 strain. J. Clin. Virol. 2023, 161, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinón-Torres, F.; Gutierrez, C.; Cáceres, A.; Weber, K.; Torres, A. How Does the Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Compare to Influenza in Spanish Adults? Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2024, 18, e13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havers, F.P.; Whitaker, M.; Melgar, M.; Chatwani, B.; Chai, S.J.; Alden, N.B.; Meek, J.; Openo, K.P.; Ryan, P.A.; Kim, S.; et al. Characteristics and Outcomes Among Adults Aged ≥60 Years Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Respiratory Syncytial Virus—RSV-NET, 12 States, July 2022–June 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerson, B.; Tseng, H.F.; Sy, L.S.; Solano, Z.; Slezak, J.; Luo, Y.; Fischetti, C.A.; Shinde, V. Severe Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Respiratory Syncytial Virus Versus Influenza Infection in Hospitalized Older Adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leija-Martínez, J.J.; Esparza-Miranda, L.A.; Rivera-Alfaro, G.; Noyola, D.E. Impact of Nonpharmaceutical Interventions during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Prevalence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Hospitalized Children with Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2024, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coultas, J.A.; Smyth, R.; Openshaw, P.J. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): A scourge from infancy to old age. Thorax 2019, 74, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri, V.; Macucci, C.; Mollo, A.; Trapani, S.; Moriondo, M.; Vignoli, M.; Ricci, S.; Indolfi, G. Impact of respiratory syncytial virus on older children: Exploring the potential for preventive strategies beyond the age of 2 years. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branche, A.R.; Saiman, L.; Walsh, E.E.; Falsey, A.R.; Sieling, W.D.; Greendyke, W.; Peterson, D.R.; Vargas, C.Y.; Phillips, M.; Finelli, L. Incidence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection Among Hospitalized Adults, 2017–2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). RSV in Adults. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/adults/index.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Abrams, E.M.; Doyon-Plourde, P.; Davis, P.; Lee, L.; Rahal, A.; Brousseau, N.; Siu, W.; Killikelly, A. Burden of disease of respiratory syncytial virus in older adults and adults considered at high risk of severe infection. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2025, 51, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, M.W.; Greenberg, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Januzzi, J.L.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Trochu, J.-N.; Butler, J. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2017, 3, 17058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, G. Innere Medizin 2023; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2022; 1003p. [Google Scholar]

- Kytömaa, S.; Hegde, S.; Claggett, B.; Udell, J.A.; Rosamond, W.; Temte, J.; Nichol, K.; Wright, J.D.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O. Association of Influenza-like Illness Activity With Hospitalizations for Heart Failure: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N.; Passavant, E.D.B.; Lüthi-Corridori, G.; Jaun, F.; Mitrovic, S.; Leuppi, J.D.; Boesing, M. Association of Comorbidities with Adverse Outcomes in Adults Hospitalized with Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study from Switzerland (2022–2024). Viruses 2025, 17, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, C.K.; Gideonse, D.; Osei-Yeboah, R.; Lehtonen, T.; Jollivet, O.; Cohen, R.A.; Urchueguía-Fornes, A.; Herrero-Silvestre, M.; López-Lacort, M.; Kramer, R.; et al. Estimation of respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospital admissions in five European countries: A modelling study. Lancet Reg. Health 2025, 51, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Reeves, R.M.; Ma, S.; Miao, Y.; Sun, S.; Orrico-Sánchez, A.; Panning, M.; Urchueguía-Fornes, A.; Vuichard-Gysin, D.; Nair, H.; et al. Estimating the respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalisation burden in older adults in European countries: A systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachinformation Beyfortus. Available online: https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/ShowText.aspx?textType=FI&lang=DE&authNr=69039 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fachinformation Arexvy. Available online: https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/ShowText.aspx?textType=FI&lang=DE&authNr=69310 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fachinformation Abrysvo. Available online: https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/ShowText.aspx?textType=FI&lang=DE&authNr=69691 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fachinformation mRESVIA. Available online: https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/ShowText.aspx?textType=FI&lang=DE&authNr=69995 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- BAG-Bulletin 47/24: Impfempfehlungen Gegen Erkrankungen Mit Dem Respiratorischen Synzytial-Virus (RSV). Available online: https://backend.bag.admin.ch/fileservice/sdweb-docs-prod-bagadminch-files/files/2025/03/18/7313288a-9ae7-4936-9ac8-6bfcc1756be2.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- AS 2025 419—Verordnung des EDI über Leistungen in der obligatorischen Krankenpflegeversicherung (Krankenpflege-Leistungsverordnung, KLV)|Fedlex. Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/oc/2025/419/de (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Schweizerischer Impfplan 2025. Available online: https://backend.bag.admin.ch/fileservice/sdweb-docs-prod-bagadminch-files/files/2025/06/24/043d49cc-dba5-487f-940d-2aec4b2f4d9f.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Boesing, M.; Albrich, W.; Bridevaux, P.-O.; Charbonnier, F.; Clarenbach, C.; Fellrath, J.-M.; Gianella, P.; Kern, L.; Latshang, T.; Pavlov, N.; et al. Vaccination in adult patients with chronic lung diseases. Praxis 2024, 113, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bally-von Passavant, E.D.; Joseph, N.; Kräutler, N.J.; McCarthy-Pontier, D.; Lüthi-Corridori, G.; Jaun, F.; Leuppi, J.D.; Boesing, M. Burden and Characteristics of RSV-Associated Hospitalizations in Switzerland: A Nationwide Analysis from 2017 to 2023. Viruses 2025, 17, 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111407

Bally-von Passavant ED, Joseph N, Kräutler NJ, McCarthy-Pontier D, Lüthi-Corridori G, Jaun F, Leuppi JD, Boesing M. Burden and Characteristics of RSV-Associated Hospitalizations in Switzerland: A Nationwide Analysis from 2017 to 2023. Viruses. 2025; 17(11):1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111407

Chicago/Turabian StyleBally-von Passavant, Elisa D., Neetha Joseph, Nike Julia Kräutler, Daphne McCarthy-Pontier, Giorgia Lüthi-Corridori, Fabienne Jaun, Jörg D. Leuppi, and Maria Boesing. 2025. "Burden and Characteristics of RSV-Associated Hospitalizations in Switzerland: A Nationwide Analysis from 2017 to 2023" Viruses 17, no. 11: 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111407

APA StyleBally-von Passavant, E. D., Joseph, N., Kräutler, N. J., McCarthy-Pontier, D., Lüthi-Corridori, G., Jaun, F., Leuppi, J. D., & Boesing, M. (2025). Burden and Characteristics of RSV-Associated Hospitalizations in Switzerland: A Nationwide Analysis from 2017 to 2023. Viruses, 17(11), 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111407