An In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Autolysis and Formalin Fixation on the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus and Innate Immune Response Antigens

Abstract

1. Introduction

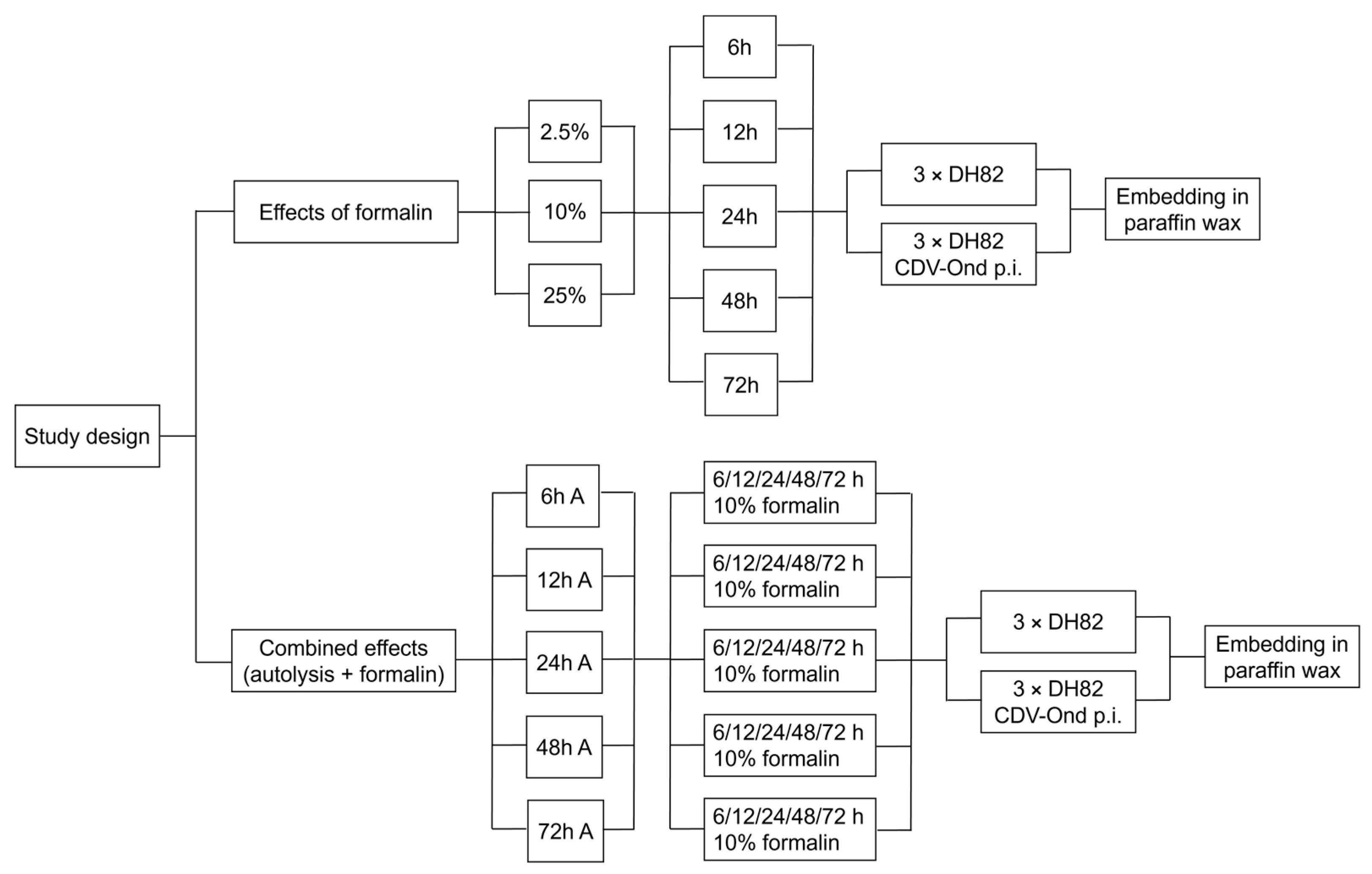

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Light Microcopy

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

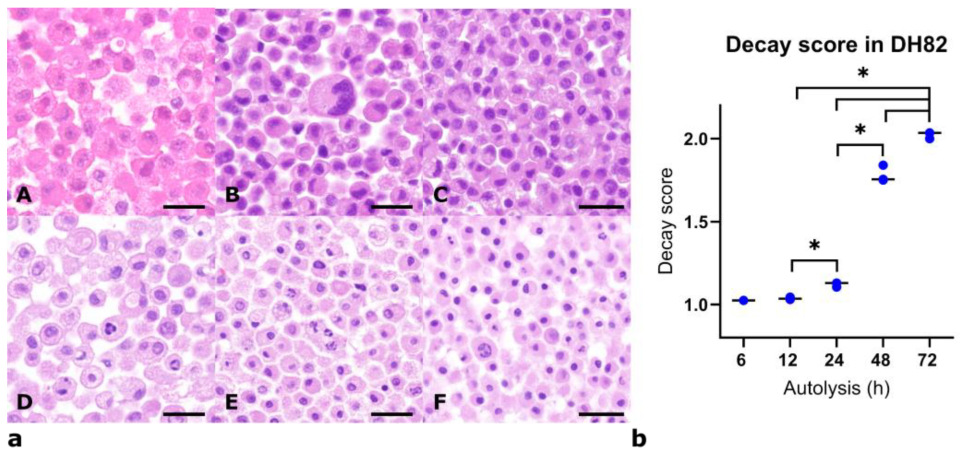

3.1. Histomorphological Assessment of DH82 Cells Under Different Fixation and Autolysis Conditions

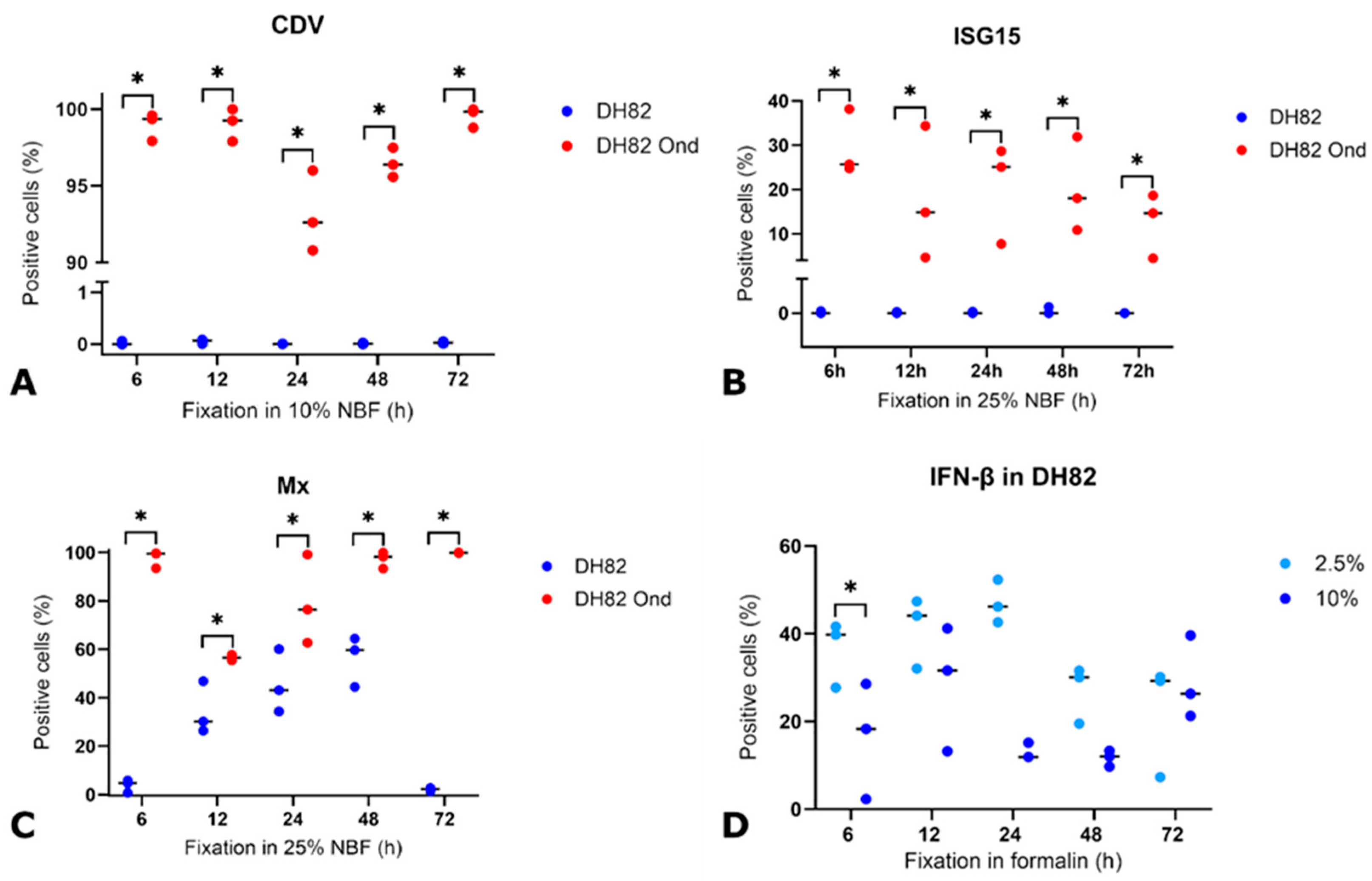

3.2. Detection of CDV Nucleoprotein Under Variable Conditions

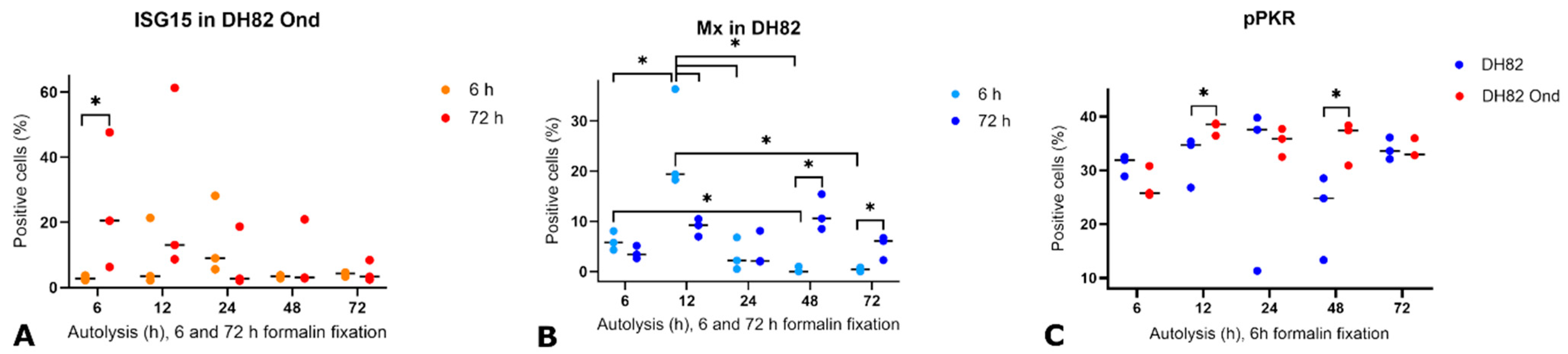

3.3. Detection and Expression of ISG15, Mx, IFN-β, Phosphorylated PKR (pPKR), and Its Stability Under Various Pre-Fixation Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Epstein, J.H.; Anthony, S.J. Viral discovery as a tool for pandemic preparedness. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, S.L.; Bodewes, R.; Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Baumgärtner, W.; Koopmans, M.P.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Schurch, A.C. Assembly of viral genomes from metagenomes. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, S.L.; Osterhaus, A.D. Virus discovery: One step beyond. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de le Roi, M.; Puff, C.; Wohlsein, P.; Pfaff, F.; Beer, M.; Baumgärtner, W.; Rubbenstroth, D. Rustrela virus as putative cause of nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis in lions. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, C.; Guerriero, P.; Pierantoni, M.; Callegari, E.; Sabbioni, S. Novel virus identification through metagenomics: A systematic review. Life 2022, 12, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.D.; Miller, M.A.; Dusold, D.; Ramos-Vara, J. Effects of prolonged formalin fixation on diagnostic immunohistochemistry in domestic animals. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 57, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, W.F.; Conway, J.A.; Dark, M.J. Comparison of histomorphology and DNA preservation produced by fixatives in the veterinary diagnostic laboratory setting. PeerJ 2014, 2, e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, C.; Miura, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Miyaishi, S. The influence of fixing condition on myoglobin stainability of striated muscle as a tool for forensic diagnosis. Leg. Med. 2024, 71, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.D.; Miller, M.A.; DuSold, D.; Ramos-Vara, J. Effects of prolonged formalin fixation on the immunohistochemical detection of infectious agents in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Vet. Pathol. 2010, 47, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Deng, C.; Su, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, M.; Tian, K.; Wu, H.; Xu, S. The effect of prolonged formalin fixation on the expression of proteins in human brain tissues. Acta Histochem. 2022, 124, 151879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, C.; Dai, D.; Johnson, C.; Mereuta, O.M.; Kallmes, D.F.; Brinjikji, W.; Kadirvel, R. Quality assessment of histopathological stainings on prolonged formalin fixed thrombus tissues retrieved by mechanical thrombectomy. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1223947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafin, D.; Theiss, A.; Roberts, E.; Borlee, G.; Otter, M.; Baird, G.S. Rapid two-temperature formalin fixation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.S.; Furusato, B.; Wong, K.; Sesterhenn, I.A.; Mostofi, F.K.; Wei, M.Q.; Zhu, Z.; Abbondanzo, S.L.; Liang, Q. Ultrasound-accelerated formalin fixation of tissue improves morphology, antigen and mRNA preservation. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, F.M.; Dark, M.J. Determining the utility of veterinary tissue archives for retrospective DNA analysis. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litlekalsoy, J.; Vatne, V.; Hostmark, J.G.; Laerum, O.D. Immunohistochemical markers in urinary bladder carcinomas from paraffin-embedded archival tissue after storage for 5–70 years. BJU Int. 2007, 99, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiurba, R.A.; Spooner, E.T.; Ishiguro, K.; Takahashi, M.; Yoshida, R.; Wheelock, T.R.; Imahori, K.; Cataldo, A.M.; Nixon, R.A. Immunocytochemistry of formalin-fixed human brain tissues: Microwave irradiation of free-floating sections. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 1998, 2, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshtalab, N.; Doré, J.J.; Smeda, J.S. Troubleshooting tissue specificity and antibody selection: Procedures in immunohistochemical studies. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2010, 61, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauber, Z.; Stetkova, I.; Cizkova, K. Influence of fixation method and duration of archiving on immunohistochemical staining intensity in embryonic and fetal tissues. Ann. Anat. 2019, 224, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, M.; Chott, A.; Fabiano, A.; Battifora, H. Effect of formalin tissue fixation and processing on immunohistochemistry. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000, 24, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyck, L.; Dalmau, I.; Chemnitz, J.; Finsen, B.; Schrøder, H.D. Immunohistochemical markers for quantitative studies of neurons and glia in human neocortex. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008, 56, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kap, M.; Lam, K.H.; Ewing-Graham, P.; Riegman, P. A reference image-based method for optimization of clinical immunohistochemistry. Histopathology 2015, 67, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, F.; Degl’Innocenti, S.; Aytaş, Ç.; Pirone, A.; Cantile, C. Morphological and immunohistochemical changes in progressive postmortem autolysis of the murine brain. Animals 2024, 14, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madea, B. Is there recent progress in the estimation of the postmortem interval by means of thanatochemistry? Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 151, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albloshi, A.M.K. Postmortem interval estimation of time since death: Impact of non-histone binding proteins, immunohistochemical, and histopathological changes in vivo. J. Med. Life 2024, 17, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, F.; Wehner, H.D.; Schieffer, M.C.; Subke, J. Delimitation of the time of death by immunohistochemical detection of insulin in pancreatic beta-cells. Forensic Sci. Int. 1999, 105, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilakopoulou, M.; Parisi, F.; Siddiqui, S.; England, A.M.; Zarella, E.R.; Anagnostou, V.; Kluger, Y.; Hicks, D.G.; Rimm, D.L.; Neumeister, V.M. Preanalytical variables and phosphoepitope expression in FFPE tissue: Quantitative epitope assessment after variable cold ischemic time. Lab. Invest. 2015, 95, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.; Cocimano, G.; Roccuzzo, S.; Russo, I.; Piombino-Mascali, D.; Márquez-Grant, N.; Zammit, C.; Esposito, M.; Sessa, F. New trends in immunohistochemical methods to estimate the time since death: A review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, S.; Treglia, M.; Pallocci, M.; Bonfiglio, R.; Giacobbi, E.; Passalacqua, P.; Cammarano, A.; D’Ovidio, C.; Marsella, L.T.; Scimeca, M. Antigenicity preservation is related to tissue characteristics and the post-mortem interval: Immunohistochemical study and literature review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral-Arca, R.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Martinón-Torres, F.; Salas, A. A 2-transcript host cell signature distinguishes viral from bacterial diarrhea and it is influenced by the severity of symptoms. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Flores, R.; Mai, H.N.; Kanrar, S.; Aranguren Caro, L.F.; Dhar, A.K. Genome reconstruction of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) from archival Davidson’s-fixed paraffin embedded shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) tissue. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.J.; Willcox, A.; Hilton, D.A.; Tauriainen, S.; Hyoty, H.; Bone, A.J.; Foulis, A.K.; Morgan, N.G. Use of antisera directed against dsRNA to detect viral infections in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. J. Clin. Virol. 2010, 49, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, C.; Røge, R.; Fred, Å.; Wanders, A. Immunohistochemical detection of double-stranded RNA in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Apmis 2023, 131, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.N.; Liang, Z.; Lipton, H.L. Double-stranded RNA is detected by immunofluorescence analysis in RNA and DNA virus infections, including those by negative-stranded RNA viruses. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 9383–9392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, N.M.; Bordelon, H.; Wang, K.K.; Albert, L.E.; Wright, D.W.; Haselton, F.R. Comparison of three magnetic bead surface functionalities for RNA extraction and detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6062–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Wagner, V.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5059–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, S. Double-stranded RNA sensors and modulators in innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 37, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, O.; Kochs, G.; Weber, F. Interferon, Mx, and viral countermeasures. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2007, 18, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.R.; Kaminski, J.J.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection. Viruses 2011, 3, 920–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O’Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2008, 1143, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.R.; Abraham, R.; Sundaram, S.; Sreekumar, E. Interferon regulated gene (IRG) expression-signature in a mouse model of chikungunya virus neurovirulence. J. Neurovirol. 2017, 23, 886–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Deng, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, G. Identification of new type I interferon-stimulated genes and investigation of their involvement in IFN-β activation. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Vidal, S.M. Functional diversity of Mx proteins: Variations on a theme of host resistance to infection. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, O.; Kochs, G. Interferon-induced mx proteins: Dynamin-like GTPases with antiviral activity. Traffic 2002, 3, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.S.; Emerman, M.; Malik, H.S. An evolutionary perspective on the broad antiviral specificity of MxA. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, D.; Gerhauser, I. Interferon-stimulated genes-mediators of the innate immune response during canine distemper virus infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, A.J.; Williams, B.R. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, C.E. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 778–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.H.; Laurent-Rolle, M.; Grove, T.L.; Hsu, J.C. Interferon-stimulated genes and immune metabolites as broad-spectrum biomarkers for viral infections. Viruses 2025, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levraud, J.P.; Jouneau, L.; Briolat, V.; Laghi, V.; Boudinot, P. IFN-stimulated genes in zebrafish and humans define an ancient arsenal of antiviral immunity. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 3361–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, T.M.; Lew, A.M.; Chong, M.M. MicroRNA-independent roles of the RNase III enzymes Drosha and Dicer. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 130144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Doudna, J.A. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, O.; Stertz, S.; Kochs, G. The Mx GTPase family of interferon-induced antiviral proteins. Microbes Infect. 2007, 9, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, G.; Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Cirone, F.; Lucente, M.S.; Lorusso, E.; Di Trani, L.; Buonavoglia, C. Detection of canine distemper virus in dogs by real-time RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 136, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambulli, S.; Sharp, C.R.; Acciardo, A.S.; Drexler, J.F.; Duprex, W.P. Mapping the evolutionary trajectories of morbilliviruses: What, where and whither. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 16, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beineke, A.; Baumgärtner, W.; Wohlsein, P. Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update. One Health 2015, 1, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiselhardt, F.; Peters, M.; Jo, W.K.; Schadenhofer, A.; Puff, C.; Baumgärtner, W.; Kydyrmanov, A.; Kuiken, T.; Piewbang, C.; Techangamsuwan, S.; et al. Development and validation of a pan-genotypic real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay to detect canine distemper virus and phocine distemper virus in domestic animals and wildlife. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0250521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Buonavoglia, C. Canine distemper virus. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2008, 38, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevelde, M.; Zurbriggen, A. Demyelination in canine distemper virus infection: A review. Acta Neuropathol. 2005, 109, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, F.; Contioso, V.B.; Stein, V.M.; Carlson, R.; Tipold, A.; Ulrich, R.; Puff, C.; Baumgärtner, W.; Spitzbarth, I. Passage-dependent morphological and phenotypical changes of a canine histiocytic sarcoma cell line (DH82 cells). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 163, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, L.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Xia, X.; Zheng, W.; Xue, X. RNA sequencing analyses of gene expressions in a canine macrophages cell line DH82 infected with canine distemper virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 80, 104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellman, M.L.; Krakowka, S.; Jacobs, R.M.; Kociba, G.J. A macrophage-monocyte cell line from a dog with malignant histiocytosis. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 1988, 24, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puff, C.; Krudewig, C.; Imbschweiler, I.; Baumgärtner, W.; Alldinger, S. Influence of persistent canine distemper virus infection on expression of RECK, matrix-metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in a canine macrophage/monocytic tumour cell line (DH82). Vet. J. 2009, 182, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.; King, H.; Hurst, J.; Tanner, G.; Khazin, L.; Thompson, P.; Gray, A.; Gahir, N.; Cartlidge, C.; Farooq, Z.; et al. Decreasing formalin concentration improves quality of DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens without compromising tissue morphology or immunohistochemical staining. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 73, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.W.; Miller, A.D.; Rissi, D.R. Effects of autolysis and prolonged formalin fixation on histomorphology and immunohistochemistry of normal canine brain tissue: An experimental study. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2024, 36, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzlow, N.; Neal, D.; Stern, A.W.; Prakoso, D.; Liu, J.J.; Delcambre, G.H.; Beachboard, S.; Long, M.T. Feasibility of using tissue autolysis to estimate the postmortem interval in horses. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2021, 33, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, P.K.; Purkait, S.; Singh, S.R.; Mishra, P.R. Decay score: A guide to the immunoreactivity of human pancreatic islets in autopsy specimen. Folia Morphol. 2022, 81, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnikova, I.; Schreckenbach, M.N.; Kristensen, M.P.; Papanikolaou, L.L.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S. Usability of immunohistochemistry in forensic samples with varying decomposition. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2018, 39, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chludzinski, E.; Klemens, J.; Ciurkiewicz, M.; Geffers, R.; Pöpperl, P.; Stoff, M.; Shin, D.L.; Herrler, G.; Beineke, A. Phenotypic and transcriptional changes of pulmonary immune responses in dogs following canine distemper virus infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de le Roi, M.; Gerhards, H.; Fayyad, A.; Boelke, M.; Becker, S.C.; Volz, A.; Gerhauser, I.; Baumgärtner, W.; Puff, C. Evaluating the potential of anti-dsRNA antibodies as an alternative viral sensing tool in encephalitides of different species. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernandez, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydemann, L.; Ciurkiewicz, M.; Störk, T.; Zdora, I.; Hülskötter, K.; Gregor, K.M.; Michaely, L.M.; Reineking, W.; Schreiner, T.; Beythien, G.; et al. Respiratory long COVID in aged hamsters features impaired lung function post-exercise with bronchiolization and fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.M.; Schechter, R.; Miller, K.E. Fixative composition alters distributions of immunoreactivity for glutaminase and two markers of nociceptive neurons, Nav1.8 and TRPV1, in the rat dorsal root ganglion. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2010, 58, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marzo, A.M.; Fedor, H.H.; Gage, W.R.; Rubin, M.A. Inadequate formalin fixation decreases reliability of p27 immunohistochemical staining: Probing optimal fixation time using high-density tissue microarrays. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alstine, W.G.; Popielarczyk, M.; Albregts, S.R. Effect of formalin fixation on the immunohistochemical detection of PRRS virus antigen in experimentally and naturally infected pigs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2002, 14, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.K.; Watanabe, K.; Michishita, M.; Hatai, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Doge, S.; Ochiai, K.; Kato, S.; Goto-Koshino, Y.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Standardization of tissue handling in veterinary pathology: How fixation affects morphological and molecular examination results. Vet. Pathol. 2025, 62, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryska, A.; Sapino, A.; Landolfi, S.; Valero, I.S.; Cajal, S.R.Y.; Oliveira, P.; Detillo, P.; Lianas, L.; Frexia, F.; Nicolosi, P.A.; et al. Glyoxal acid-free (GAF) histological fixative is a suitable alternative to formalin: Results from an open-label comparative non-inferiority study. Virchows Arch. 2024, 485, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucevic, D.D.; Seidman, M.A.; Mesaki, K.; Guan, Z.; Juvet, S.; Liu, M.; Keshavjee, S.; Murphy, K. A novel tissue preservation and transport solution as a substitute for formalin. Lab. Invest. 2023, 103, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelb, A.B.; Kamel, O.W.; LeBrun, D.P.; Warnke, R.A. Estimation of tumor growth fractions in archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using two anti-PCNA/Cyclin monoclonal antibodies. Factors affecting reactivity. Am. J. Pathol. 1992, 141, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.C.; Ojok, L.; Mariner, J.C. Immunohistochemical detection of rinderpest virus: Effects of autolysis and period of fixation. Res. Vet. Sci. 1996, 60, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radonic, T.; Duin, S.; Vos, W.; Kortman, P.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Thunnissen, E. Influence of preanalytical variables on performance of delta-like protein 3 (DLL3) predictive immunohistochemistry. Virchows Arch. 2021, 478, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleszewski, J.; Lu, J.; Fox-Talbot, K.; Halushka, M.K. Robust immunohistochemical staining of several classes of proteins in tissues subjected to autolysis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2007, 55, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelstring, R.J.; Allred, D.C.; Esther, R.J.; Lampkin, S.R.; Banks, P.M. Differential antigen preservation during tissue autolysis. Hum. Pathol. 1991, 22, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.M.; Alejo, A.; Martín, V.; Sevilla, N. Viral pathogen-induced mechanisms to antagonize mammalian interferon (IFN) signaling pathway. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1423–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Hur, S. Cellular origins of dsRNA, their recognition and consequences. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siering, O.; Sawatsky, B.; Pfaller, C.K. C protein is essential for canine distemper virus virulence and pathogenicity in ferrets. J. Virol. 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, C.K.; Radeke, M.J.; Cattaneo, R.; Samuel, C.E. Measles virus C protein impairs production of defective copyback double-stranded viral RNA and activation of protein kinase R. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zav’yalov, V.P.; Hämäläinen-Laanaya, H.; Korpela, T.K.; Wahlroos, T. Interferon-inducible myxovirus resistance proteins: Potential biomarkers for differentiating viral from bacterial infections. Clin. Chem. 2019, 65, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, B.F.; Ambrus, A.; Storts, R.W. Immunohistochemical evaluation of mx protein expression in canine encephalitides. Vet. Pathol. 2006, 43, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebaw, D.; Akelew, Y.; Adugna, A.; Teffera, Z.H.; Belew, H.; Selabat, B.; Getie, M.; Mulu, A.T.; Atnaf, A. Recent updates of interferon-derived myxovirus resistance protein A as a biomarker for acute viral infection. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, D.L.; Fox, B.A.; Yager, T.D.; Bhide, S.; Cermelli, S.; McHugh, L.C.; Seldon, T.A.; Brandon, R.A.; Sullivan, E.; Zimmerman, J.J.; et al. A four-biomarker blood signature discriminates systemic inflammation due to viral infection versus other etiologies. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandstra, J.; Jongerius, I.; Kuijpers, T.W. Future biomarkers for infection and inflammation in febrile children. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 631308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Kang, M.G.; Kwak, C.; Kang, M.; Kim, B.; Rhee, H.W.; Kim, V.N. PKR senses nuclear and mitochondrial signals by interacting with endogenous double-stranded RNAs. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holicek, P.; Guilbaud, E.; Klapp, V.; Truxova, I.; Spisek, R.; Galluzzi, L.; Fucikova, J. Type I interferon and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhipa, A.S.; Boscaro, V.; Gallicchio, M.; Patel, S. The curious case of type I interferon signaling in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, L.; Yuan, J. Bi-directional regulation of type I interferon signaling by heme oxygenase-1. iScience 2024, 27, 109185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goubau, D.; Deddouche, S.; Reis e Sousa, C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity 2013, 38, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.J. Interplay between janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling activated by type I interferons and viral antagonism. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demasking | Blocking Serum | Primary Antibody, Source | Secondary Antibody | ABC | DAB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDV nucleoprotein | 20′ citrate buffer, microwave (800 W), 20′ cooling at RT | 120 µL goat normal serum, Dilution: 1:5 | D110, Prof. Dr. Zurbriggen, University of Bern, Switzerland, mouse monoclonal Dilution: 1:800 | Goat-anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), biotinylated, VectorLab, Newark, CA, USA | 120 µL/ slide; 1000 µL PBS + 15 µL reagent A + 15 µL reagent B | 0.1 g DAB, 200 mL PBS, 250 µL H2O2 |

| Interferon-β | 20′ citrate buffer, microwave (800 W), 20′ cooling at RT | IFN beta antibody (PA5-102429), Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA, Lot #ZC4272091, rabbit polyclonal Dilution: 1:5000 | Goat-anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L), biotinylated, VectorLab, Newark, CA, USA | |||

| Myxovirus resistance protein | 20′ citrate buffer, microwave (800 W), 20′ cooling at RT | M143, Prof. Dr. Haller and PD Dr. Koch, University Medical Center Freiburg, Germany, mouse monoclonal Dilution: 1:500 | Goat-anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), biotinylated, VectorLab, Newark, CA, USA | |||

| Phosphorylated protein kinase R | 20′ citrate buffer, microwave (800 W), 20′ cooling at RT | pPKR, phosphor T446, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA, Ab32036, rabbit monoclonal Dilution: 1:8000 | Goat-anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L), biotinylated, VectorLab, Newark, CA, USA | |||

| Interferon stimulated gene 15 | 20′ citrate buffer, microwave (800 W), 20′ cooling at RT | ISG15 (F-9), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, Sc-50366, mouse monoclonal Dilution: 1:1600 | Goat-anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), biotinylated, VectorLab, Newark, CA, USA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerhards, H.; Rohn, K.; Puff, C.; Baumgärtner, W. An In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Autolysis and Formalin Fixation on the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus and Innate Immune Response Antigens. Viruses 2025, 17, 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121575

Gerhards H, Rohn K, Puff C, Baumgärtner W. An In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Autolysis and Formalin Fixation on the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus and Innate Immune Response Antigens. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121575

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerhards, Hannah, Karl Rohn, Christina Puff, and Wolfgang Baumgärtner. 2025. "An In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Autolysis and Formalin Fixation on the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus and Innate Immune Response Antigens" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121575

APA StyleGerhards, H., Rohn, K., Puff, C., & Baumgärtner, W. (2025). An In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Autolysis and Formalin Fixation on the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus and Innate Immune Response Antigens. Viruses, 17(12), 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121575