Contrasting Evolutionary Dynamics and Global Dissemination of the DNA-A and DNA-B Components of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Retrieval and Multiple Sequence Alignment

2.2. Recombination Analysis

2.3. Evolutionary Time, Contemporary Dissemination and Phylogeny

2.4. Genetic Diversity of WmCSV Population

2.5. Natural Selection Inference

3. Results

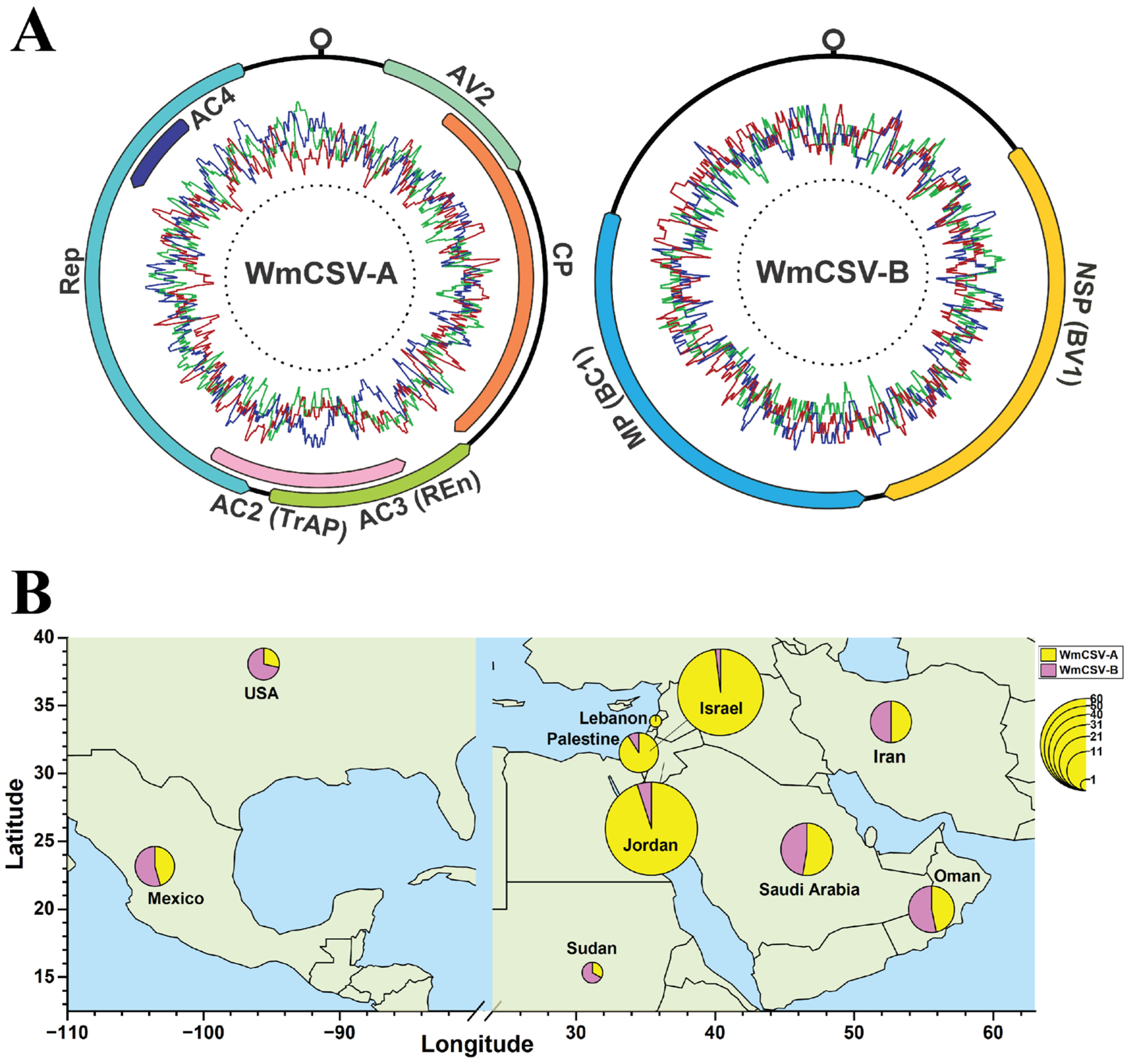

3.1. Geographical Distribution of ToLCNDV

3.2. Evolutionary Time Estimation

3.3. Phylogeny and Phylogeography of WmCSV

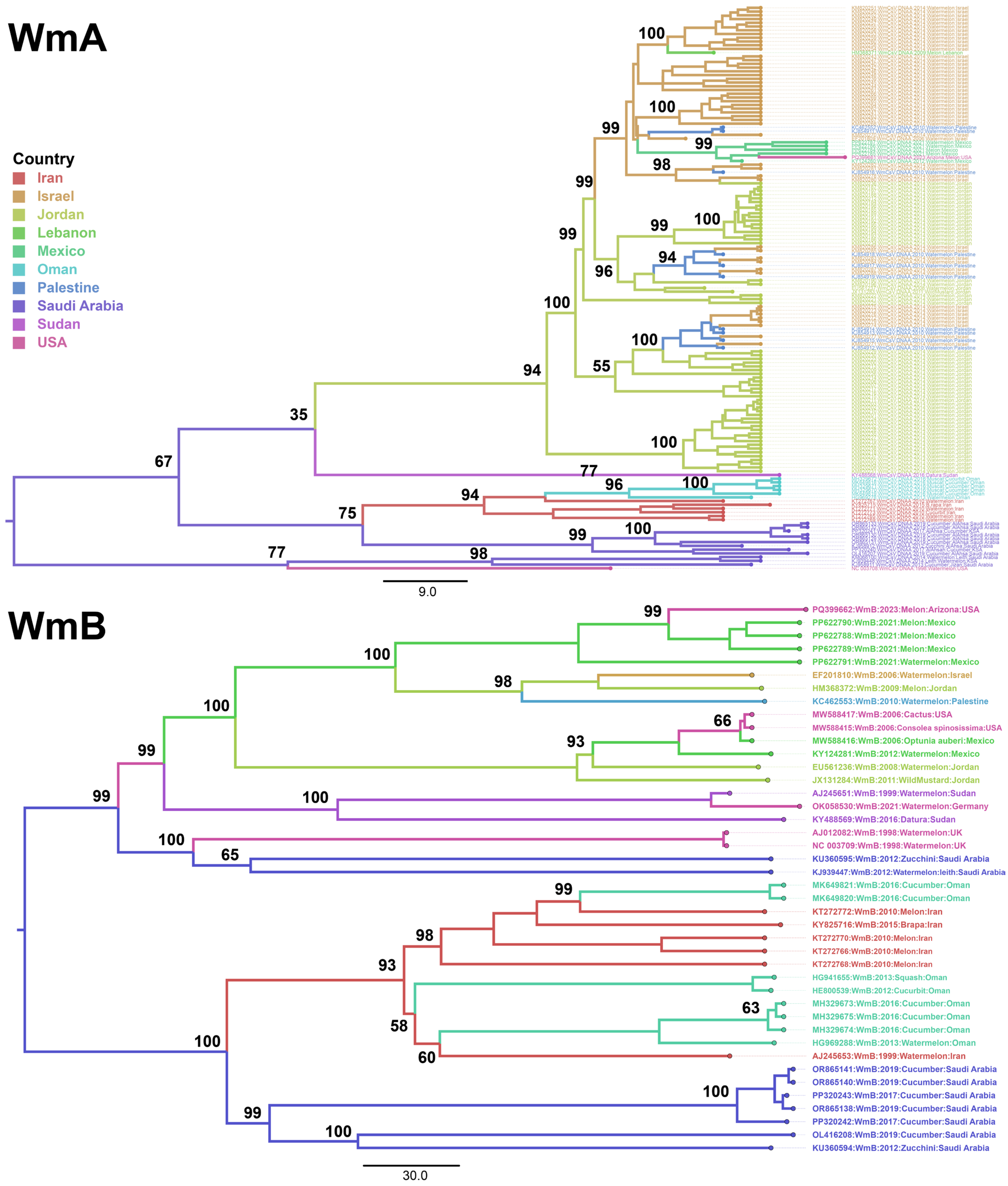

3.3.1. Phylogeny of WmCSV

3.3.2. Phylogeographic Spread of WmCSV

3.4. Genetic Diversity Indices of WmCSV

3.4.1. GDIs in Country-Wise WmCSV Populations

3.4.2. GDIs in WmCSV-Encoded ORFs

3.4.3. Nucleotide Diversity Across the Whole Genome

3.4.4. Genetic Differentiation Between WmCSV Populations

3.5. Recombination Analysis

3.5.1. RDP

3.5.2. GARD

3.6. Nucleotide Substitution Rate

3.7. Selection Pressure Inference Analysis

3.7.1. Neutrality Indices

3.7.2. Mismatch Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WmA | watermelon chlorotic stunt virus DNA-A |

| WmB | watermelon chlorotic stunt virus DNA-B |

| CP | coat protein |

| Rep | replication-associated protein |

| TrAP | transcriptional activator protein |

| REn | replication enhancer protein |

| MP | movement protein |

| NSP | nuclear shuttle protein |

| TD | Tajima’s D test |

| FLD | Fu and Li’s D test |

| ORF | open reading frame |

| FUBAR | Fast, Unconstrained Bayesian AppRoximation |

| FEL | Fixed Effects Likelihood |

| RDP | recombination detection program |

| ESS | effective sample size |

| HPD | highest posterior density |

References

- Hickerson, M.J.; Carstens, B.C.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Crandall, K.A.; Graham, C.H.; Johnson, J.B.; Rissler, L.; Victoriano, P.F.; Yoder, A.D. Phylogeography’s past, present, and future: 10 years after Avise, 2000. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010, 54, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avise, J.C. Phylogeography: Retrospect and prospect. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggins, L.; Treml, E.A.; Possingham, H.P.; Riginos, C. Seascape features, rather than dispersal traits, predict spatial genetic patterns in co-distributed reef fishes. J. Biogeogr. 2016, 43, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefeuvre, P.; Moriones, E. Recombination as a motor of hosts witches and virus emergence: Gemini viruses as case studies. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 10, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e3000003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondong, V.N. Gemini virus protein structure and function. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley-Bowdoin, L.; Bejarano, E.R.; Robertson, D.; Mansoor, S. Geminiviruses: Masters at redirecting and reprogramming plant processes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhubaishi, A.A.; Walkey, D.G.A.; Webb, M.J.W.; Bolland, C.J.; Cook, A.A. A survey of horticultural plant virus diseases in the Yemen Arab Republic. FAO Plant Prot. Bull. 1987, 35, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kheyr-Pour, A.; Bananej, K.; Dafalla, G.A.; Caciagli, P.; Noris, E.; Ahoonmanesh, A.; Lecoq, H.; Gronenborn, B. Watermelon chlorotic stunt virus from Sudan and Iran: Sequence comparisons and identification of a whitefly-transmission determinant. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, A.; Sufrin-Ringwald, T.; Dayan-Glick, C.; Guenoune-Gelbart, D.; Livneh, O.; Zaccai, M.; Lapidot, M. Watermelon chlorotic stunt and Squash leaf curl begomoviruses—New threats to cucurbit crops in the Middle East. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 58, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musa, A.; Anfoka, G.; Al-Abdulat, A.; Misbeh, S.; HajAhmed, F.; Otri, I. Watermelon chlorotic stunt virus (WmCSV): A serious disease threatening watermelon production in Jordan. Virus Genes 2011, 43, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Mallah, O.B.; Abu-Zeitoun, S.Y. Molecular Characterization of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus (WmCSV) from Palestine. Viruses 2014, 6, 2444–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.J.; Akhtar, S.; Briddon, R.W.; Ammara, U.; Al-Matrooshi, A.M.; Mansoor, S. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus Originating from Oman. Viruses 2012, 4, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.; Ahmad, M.; Al-Shahwan, I.; Brown, J.; Idris, A. First report of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus infecting watermelon in Saudi Arabia. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, M.N.; Almaghasla, M.I.; Tahir, M.N.; El-Ganainy, S.M.; Chellappan, B.V.; Arshad, M.; Drou, N. High-throughput sequencing discovered diverse monopartite and bipartite begomoviruses infecting cucumbers in Saudi Arabia. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1375405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, M.N. Identification and molecular analysis of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus infecting snake gourd in Saudi Arabia. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2024, 52, 13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, A.A.; Sattar, M.N.; Alhudaib, K.A.; Soliman, A.M. Identification of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus from watermelon and zucchini in Saudi Arabia. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 41, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Durán, G.; Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Morales-Aguilar, J.J.; Camacho-Beltrán, E.; Romero-Romero, J.L.; Rivera-Acosta, M.A.; Leyva-López, N.E.; Arroyo-Becerra, A.; Méndez-Lozano, J. Molecular and biological characterization of Watermelon chlorotic stunt virus(WmCSV): An Eastern Hemisphere begomo virus introduced in the Western Hemisphere. Crop Prot. 2018, 103, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenele, R.S.; Bhaskara, A.; Cobb, I.N.; Majure, L.C.; Salywon, A.M.; Avalos-Calleros, J.A.; Argüello-Astorga, G.R.; Schmidlin, K.; Roumagnac, P.; Ribeiro, S.G.; et al. Identification of the Begomoviruses Squash Leaf Curl Virus and Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus in Various Plant Samples in North America. Viruses 2021, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintermantel, W.M.; Tian, T.; Chen, C.; Winarto, N.; Szumski, S.; Hladky, L.J.; Gurung, S.; Palumbo, J.C. Emergence of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus in melon and watermelon in the South western United States. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot, M.; Gelbart, D.; Gal-On, A.; Sela, N.; Anfoka, G.; HajAhmed, F.; Abou-Jawada, Y.; Sobh, H.; Mazyad, H.; Aboul-Ata, A.-A.; et al. Frequent migration of introduced cucurbit-infecting begomoviruses among Middle Eastern countries. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Sattar, M.N.; Shahid, M.S.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Briddon, R.W. Interaction of water melon chlorotic stunt virus with satellites. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2021, 50, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Heydarnejad, J.; Massumi, H.; Varsani, A. Analysis of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus and tomato leaf curl Palampur virus mixed and pseudo-recombination infections. Virus Genes 2015, 51, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoq, H.; Desbiez, C. Viruses of cucurbit crops in the Mediterranean region: An ever-changing picture. In Advances in Virus Research; Loebenstein, G., Lecoq, H., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 84, pp. 67–126. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Castillo, J.; Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Sánchez-Campos, S. Emerging virus diseases transmitted by white flies. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.R.; Macedo, M.A.; Maliano, M.R.; Soto-Aguilar, M.; Souza, J.O.; Briddon, R.W.; Kenyon, L.; RiveraBustamante, R.F.; Zerbini, F.M.; Adkins, S.; et al. World Management of Gemini viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 637–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Shafiq, M.; Sattar, M.N.; Ali, I.; Khurshid, M.; Farooq, U.; Munir, M. Genetic diversity, evolutionary dynamics, and on going spread of pedilanthus leaf curl virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biebricher, C.K.; Domingo, E. Advantage of the high genetic diversity in RNA viruses. Future Virol. 2007, 2, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątek-Kościelna, B.; Kałużna, E.; Strauss, E.; Nowak, J.; Bereszyńska, I.; Gowin, E.; Wysocki, J.; Rembowska, J.; Barcińska, D.; Mozer-Lisewska, I.; et al. PrevalenceofIFNL3rs4803217single nucleotide polymorphism and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3815–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furió, V.; Moya, A.; Sanjuán, R. The cost of replication fidelity in an RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10233–10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.W.; Holland, J.J. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13910–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.; Shackleton, L.A.; Holmes, E.C. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: Patterns and determinants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelton, L.A.; Parrish, C.R.; Truyen, U.; Holmes, E.C. High rate of viral evolution associated with the emergence of carnivore parvovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, S.; Holmes, E.C. Validation of high rates of nucleotide substitution ningemini viruses: Phylogenetic evidence from East African cassava mosaic viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.T.M.; Silva, J.C.F.; Silva, F.N.; Castillo-Urquiza, G.P.; Silva, F.F.; Seah, Y.M.; Mizubuti, E.S.G.; Duffy, S.; Zerbini, F.M. The diversification of begomovirus populations is predominantly driven by mutational dynamics. Virus Evol. 2017, 3, vex005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, S.E.; vandenBosch, F.; Jeger, M.J. Factors influencing begomoviruse volution and their increasing global significance: Implications for sustainable control. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, M.N.; Khurshid, M.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Iqbal, Z. Identification and estimation of sequence variation dynamics of Tomato leaf curl Palampur virus and betasatellite complex infecting a new weed host. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Lefeuvre, P.; Varsani, A.; Hoareau, M.; Semegni, J.-Y.; Dijoux, B.; Vincent, C.; Reynaud, B.; Lett, J. -M. Complexrecombination patterns arising during geminivirus coinfections preserve and demarcate biologically important intra-genome inter action networks. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Lai, H. -C.; Lin, C. -C.; Neoh, Z.Y.; Tsai, W. -S. Genetic diversity, pathogenicity and pseudo recombination of cucurbit-infecting begomoviruses in Malaysia. Plants 2021, 10, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Varsani, A.; Roumagnac, P.; Botha, G.; Maslamoney, S.; Schwab, T.; Kelz, Z.; Kumar, V.; Murrell, B. RDP5: A c omputer program for analyzing recombination in, and removing signals of recombination from, nucleotide sequence data sets. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veaa087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Lam, T.T.; Max Carvalho, L.; Pybus, O.G. Exploring the temporal structure of heterochronous sequences using TempEst (formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2016, 2, vew007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baele, G.; Ji, X.; Hassler, G.W.; McCrone, J.T.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Holbrook, A.J.; Lemey, P.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A.; et al. BEASTX for Bayesian phylogenetic, phylogeographic and phylodynamic inference. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Jin, J.; Zou, W.; Liao, F.; Shen, J. Geographically driven adaptation of chilli veinal mottle virus revealed by genetic diversity analysis of the coat protein gene. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.; Shank, S.D.; Spielman, S.J.; Li, M.; Muse, S.V.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Datamonkey 2.0: A modern web application for characterizing selective and other evolutionary processes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargette, D.; Konate, G.; Fauquet, C.; Muller, E.; Peterschmitt, M.; Thresh, J.M. Molecular ecology and emergence of tropical plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, Z.; Alshoaibi, A.; AlHashedi, S.A.; Sattar, M.N.; Ramadan, K.M.A. Deciphering the genetic landscape of tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus: Dynamic and region-specific diversity revealed by comprehensive sequence analyses. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briddon, R.W.; Patil, B.L.; Bagewadi, B.; Nawaz-ul-Rehman, M.S.; Fauquet, C.M. Distinct evolutionary histories of the DNA-A and DNA-B components of bipartite begomoviruses. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Z. Spatial distribution and genetic diversity of TYLCV in Saudi Arabia. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2025, 71, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, C.A.D.; Godinho, M.T.; Mar, T.B.; Ferro, C.G.; Sande, O.F.L.; Silva, J.C.; Ramos-Sobrinho, R.; Nascimento, R.N.; Assunção, I.; Lima, G.S.A.; et al. Evolutionary dynamics of bipartite begomoviruses revealed by complete genome analysis. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 3747–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Hoyer, J.S.; Duffy, S. Limited role of recombination in the global diversification of begomovirus DNA-B proteins. Virus Res. 2023, 323, 198959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, J.S.; Fondong, V.N.; Sangre, A.; Otim-Nape, G.W.; Ogwal, S.; Fauquet, C.M. Recombination, pseudo recombination and synergism of geminiviruses are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset, F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics 1997, 145, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-J.; He, E.-Q.; Bao, W. -Q.; Chen, J. -S.; Sun, S. -R.; Gao, S. -J. Comparative genomics reveals insights into genetic variability and molecular evolution among sugar cane yellow leaf virus populations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7149. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, T.; Umar, M.; She, X.; Tang, Y.; He, Z. Molecular phylogenetics and evolutionary analysis of a highly recombinant begomovirus, Cotton leaf curl Multan virus, and associated satellites. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitharani, R.; Chellappan, P.; Pita, J.S.; Fauquet, C.M. Differential roles of AC2 and AC4 of cassava geminiviruses in mediating synergism and suppression of post transcriptional gene silencing. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9487–9498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, Z.; Sattar, M.N.; Kvarnheden, A.; Mansoor, S.; Briddon, R.W. Effects of the mutation of selected genes of Cotton leaf curl Kokhranvirusoninfectivity, symptoms and the maintenance of Cotton leaf curl Multan beta satellite. Virus Res. 2012, 169, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Shafiq, M.; Mansoor, S.; Briddon, R.W. Analysis of the effects of the mutation of selected genes of pedilanthus leaf curl virus on infectivity, symptoms and the maintenance of tobacco leaf curl beta satellite. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 44, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, K.; Bedford, I.D.; Stanley, J. Pathogenicity of a natural recombinant associated with Ageratum yellow vein disease: Implications for geminiviruse volution and disease etiology. Virology 2001, 282, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Zhou, X. Pathogenicity of a naturally occurring recombinant DNA satellite associated with tomato yellow leaf curl China virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Barro, P.J.; Liu, S.-S.; Boykin, L.M.; Dinsdale, A.B. Bemisiatabaci: A Statement of Species Status. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | No. of Sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| WmA | WmB | |

| Saudi Arabia | 12 | 9 |

| Oman | 7 | 8 |

| Sudan | 1 | 2 |

| Iran | 6 | 6 |

| Palestine | 10 | 1 |

| Lebanon | 1 | 0 |

| Jordan | 57 | 3 |

| Israel | 51 | 1 |

| USA | 2 | 5 |

| Mexico | 5 | 6 |

| Total | 152 | 42 |

| Dataset | Virus Comp | No. of Eq | InDels | S | Eta (h) | Eta (s) | Pi | ɵ−Eta | Hd | k | h | TD | FLD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WmA-all | WmA | 152 | 21 | 660 | 766 | 426 | 0.0119 | 0.05004 | 0.996 | 144.96 | 125 | −2.22 | −6.88 |

| Iran | 6 | 0 | 144 | 144 | 124 | 0.019 | 0.0229 | 1.00 | 52.33 | 6 | −1.10 ns | −1.12 ns | |

| Israel | 51 | 3 | 226 | 236 | 158 | 0.0068 | 0.0195 | 0.989 | 18.651 | 43 | −2.33 * | −4.33 * | |

| Jordan | 57 | 6 | 175 | 186 | 97 | 0.0059 | 0.0147 | 0.996 | 16.354 | 53 | −2.11 ** | −3.17 * | |

| Saudi Arabia | 12 | 1 | 200 | 209 | 110 | 0.0205 | 0.0259 | 0.939 | 62.02 | 9 | −0.63 ns | −0.61 ns | |

| Mexico | 5 | 2 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 0.0058 | 0.0063 | 1.00 | 15.80 | 5 | −0.88 ns | −0.76 ns | |

| Oman | 6 | 0 | 51 | 51 | 43 | 0.0068 | 0.0081 | 0.933 | 18.67 | 5 | −1.05 ns | −1.05 ns | |

| Palestine | 10 | 2 | 50 | 53 | 26 | 0.0062 | 0.0068 | 0.978 | 16.98 | 9 | 0.83 ns | −0.41 ns | |

| WmB-all | WmB | 42 | 63 | 511 | 689 | 416 | 0.0508 | 0.0854 | 0.999 | 137.45 | 40 | −1.52 | −2.19 |

| Iran | 6 | 3 | 181 | 192 | 148 | 0.0265 | 0.0308 | 1.00 | 72.13 | 6 | −1.23 ns | −0.83 ns | |

| Jordan | 3 | 6 | 161 | 163 | 121 | 0.0392 | 0.176 | 1.00 | 108.0 | 3 | N/A | N/A | |

| Saudi Arabia | 9 | 37 | 408 | 451 | 287 | 0.0504 | 0.0609 | 1.00 | 137.19 | 9 | −0.90 ns | −0.90 ns | |

| Mexico | 6 | 6 | 180 | 188 | 95 | 0.0304 | 0.030 | 1.00 | 83.87 | 6 | −0.93 ns | −0.68 ns | |

| Oman | 8 | 5 | 145 | 149 | 59 | 0.0241 | 0.0223 | 1.00 | 63.57 | 7 | 0.27 ns | 0.29 ns | |

| USA | 5 | 10 | 226 | 232 | 92 | 0.0435 | 0.041 | 0.90 | 119.60 | 4 | 0.56 ns | 0.65 ns |

| Country | Virus Comp | No. of Seq | InDel Sites | S | Eta (h) | Eta (s) | Pi (π) | ɵ from Eta | Hd | k | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WmCSV-A | WmA | 152 | 21 | 660 | 766 | 426 | 0.0119 | 0.05004 | 0.996 | 144.96 | 125 |

| AV1 (CP) | 152 | 3 | 186 | 207 | 114 | 0.0104 | 0.048 | 0.977 | 8.06 | 84 | |

| AV2 | 152 | 0 | 77 | 86 | 51 | 0.0069 | 0.043 | 0.807 | 2.47 | 50 | |

| AC1 (Rep) | 152 | 3 | 267 | 321 | 171 | 0.0131 | 0.053 | 0.988 | 14.15 | 107 | |

| AC2 (TrAP) | 152 | 0 | 102 | 123 | 72 | 0.0142 | 0.054 | 0.90 | 5.81 | 67 | |

| AC3 (REn) | 152 | 0 | 94 | 106 | 62 | 0.0107 | 0.047 | 0.794 | 4.34 | 57 | |

| AC4 | 152 | 0 | 18 | 19 | 13 | 0.0037 | 0.024 | 0.423 | 0.539 | 18 | |

| WmCSV-B | WmB | 42 | 63 | 811 | 989 | 445.85 | 0.0508 | 0.0854 | 0.999 | 137.45 | 40 |

| BV1 (NSP | 42 | 9 | 62 | 76 | 30 | 0.058 | 0.0819 | 0.977 | 12.51 | 27 | |

| BC1 (MP) | 42 | 0 | 196 | 222 | 96 | 0.0367 | 0.0563 | 0.987 | 33.73 | 32 |

| Virus | Accession # | Recomb. Event | Breakpoints | Parents | Detection Methods a | p-Value b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | Major | Minor | |||||

| WmA | KM820195 | 1 | 2655 | 2751 | Unknown | OR865131 | GBCMRS3 | 1.89 × 10−37 |

| WmB | AJ245651 | 1 | 2707 | 51 | OR865138 | KY124281 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 |

| EF201810 | 1 | 1689 | 9 | Unknown | KC462553 | BMCSL | 1.21 × 10−14 | |

| HE800539 | 1 | 990 | 1984 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| HG941655 | 2 | 2271 | 2691 | Unknown | KT272768 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| 69 | 1241 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |||

| JX131284 | 1 | 802 | 1926 | MW588415 | HM368372 | RBMCS3L | 7.24 × 10−8 | |

| KJ939447 | 1 | 2638 | 2721 | Unknown | OR865138 | GBM3L | 6.55 × 10−13 | |

| KT272766 | 1 | 990 | 1984 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| KT272768 | 1 | 113 | 1639 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| KT272770 | 1 | 1019 | 1546 | KC462553 | Unknown | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| KT272772 | 2 | 993 | 1615 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| 1591 | 2708 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |||

| HG969288 | 2 | 990 | 2693 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| 990 | 2551 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |||

| KU360594 | 2 | 329 | 728 | OR865141 | AJ245653 | RGBMCSL | 1.32 × 10−8 | |

| 1087 | 2002 | Unknown | PP320242 | MCS3L | 2.94 × 10−11 | |||

| KU360595 | 1 | 364 | 741 | NC003709 | AJ245651 | RGMB3CSL | 1.62 × 10−10 | |

| KY825716 | 1 | 2483 | 52 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| MH329673 | 1 | 2483 | 52 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| MH329674 | 2 | 2694 | 720 | KY124281 | OR865138 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| 721 | 2482 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |||

| MH329675 | 2 | 2483 | 52 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| 990 | 1984 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |||

| MK649820 | 2 | 2581 | 437 | OR865138 | KY124281 | RGBCSL | 8.62 × 10−7 | |

| 990 | 1984 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |||

| MK649821 | 1 | 990 | 1984 | Unknown | OR865138 | MCS3L | 1.15 × 10−10 | |

| OR865141 | 1 | 2607 | 13 | OR865138 | NC003709 | GMC3L | 8.10 × 10−13 | |

| PP320242 | 1 | 2608 | 2716 | OR865138 | Unknown | RGMCS3L | 1.19 × 10−36 | |

| PP320243 | 1 | 2609 | 565 | OR865138 | MH329674 | GBCS3L | 5.61 × 10−35 | |

| PP622788 | 1 | 2203 | 50 | PQ399662 | KY124281 | RGBMCS3L | 4.33 × 10−22 | |

| PP622789 | 1 | 2218 | 77 | PQ399662 | KY124281 | RGBMCS3L | 4.33 × 10−22 | |

| PP622790 | 1 | 2168 | 70 | PQ399662 | MW588415 | RGBMCS3L | 4.33 × 10−22 | |

| PP622791 | 1 | 486 | 2398 | PQ399662 | KY124281 | MCS3L | 2.51 × 10−8 | |

| Dataset | ORF | Best Model | Mean Distance (d) | dN | dS | dN/dS | TD | FLD | Expansion | Selection Sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEL | FUBAR | ||||||||||||

| NS | PS | NS | PS | ||||||||||

| WmA | WmA-all | K2 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.22 ** | −6.88 * | Yes | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| AV2 | JC + G | 0.0035 ± 0.0057 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.0105 ± 0.0025 | 0.58 | −2.64 ** | −6.70 * | Yes | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | |

| CP (AV1) | K2 + G | 0.0106 ± 0.0018 | 0.0039 ± 0.0006 | 0.0313 ± 0.0061 | 2.72 | −1.32 ** | −5.80 * | Yes | 30 | 0 | 27 | 1 | |

| Rep (AC1) | K2 + G | 0.0135 ± 0.0014 | 0.01 ± 0.0012 | 0.0203 ± 0.0039 | 1.35 | −2.46 ** | −5.69 * | Yes | 39 | 1 | 14 | 1 | |

| TrAP (AC2) | K2 + G | 0.0147 ± 0.0025 | 0.0115 ± 0.0025 | 0.0257 ± 0.0064 | 1.28 | −2.35 * | −5.99 * | Yes | 8 | 0 | 8 | 2 | |

| REn (AC3) | T92 + G | 0.011 ± 0.002 | 0.0091 ± 0.0024 | 0.0166 ± 0.0043 | 1.21 | −2.45 ** | −5.87 * | Yes | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| AC4 | JC | 0.0038 ± 0.0014 | 0.0038 ± 0.0017 | 0.004 ± 0.0022 | 1.0 | −1.30 * | −2.81 * | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Iran | T92 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.10 ns | −1.12 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Israel | K2 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.33 * | −4.33 * | Yes | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Jordan | K2 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.11 * | −3.17 * | Yes | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Saudi Arabia | K2 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.63 ns | −0.61 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Mexico | JC | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.88 ns | −0.76 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Oman | K2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.05 ns | −1.05 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Palestine | JC | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.83 ns | −0.41 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| WmB | WmB-all | GTR + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.52 ns | −2.00 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| NSP (BV1) | GTR + G | 0.0626 ± 0.0093 | 0.0338 ± 0.0081 | 0.15 ± 0.028 | 1.85 | −1.07 ns | −1.29 ns | No | 5 | 0 | 23 | 0 | |

| MP (BC1) | HKY + G | 0.0382 ± 0.0034 | 0.015 ± 0.0031 | 0.0114 ± 0.011 | 2.55 | −1.30 ns | −1.86 ns | No | 58 | 0 | 69 | 1 | |

| Iran | T92 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.23 ns | −0.83 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Jordan | T92 | -- | -- | -- | -- | N/A | N/A | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Saudi Arabia | T92 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.90 ns | −0.90 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Mexico | T92 + G | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.93 ns | −0.68 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Oman | T92 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.27 ns | 0.29 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| USA | T92 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.56 ns | 0.65 ns | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, Z. Contrasting Evolutionary Dynamics and Global Dissemination of the DNA-A and DNA-B Components of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus. Viruses 2025, 17, 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121571

Iqbal Z. Contrasting Evolutionary Dynamics and Global Dissemination of the DNA-A and DNA-B Components of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121571

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Zafar. 2025. "Contrasting Evolutionary Dynamics and Global Dissemination of the DNA-A and DNA-B Components of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121571

APA StyleIqbal, Z. (2025). Contrasting Evolutionary Dynamics and Global Dissemination of the DNA-A and DNA-B Components of Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus. Viruses, 17(12), 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121571