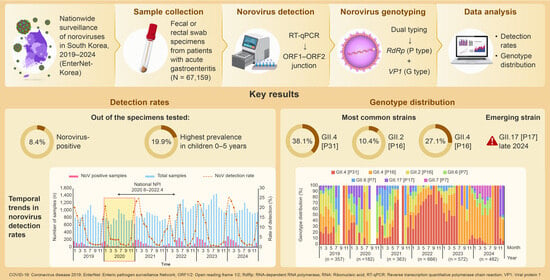

Trends in Norovirus Genotypes in South Korea, 2019–2024: Insights from Nationwide Dual Typing Surveillance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Stool Sample Collection

2.2. Norovirus Detection

2.3. Norovirus Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

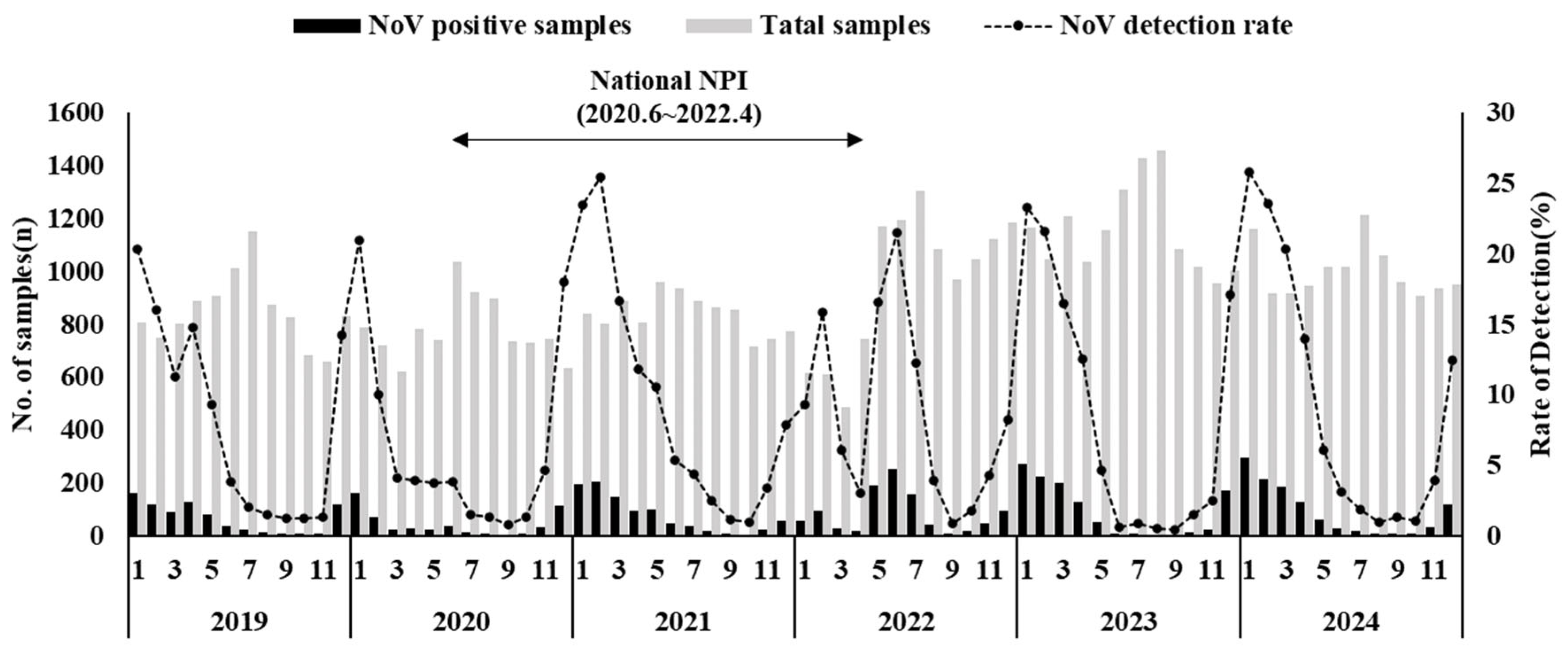

3.1. Norovirus Detection Rate

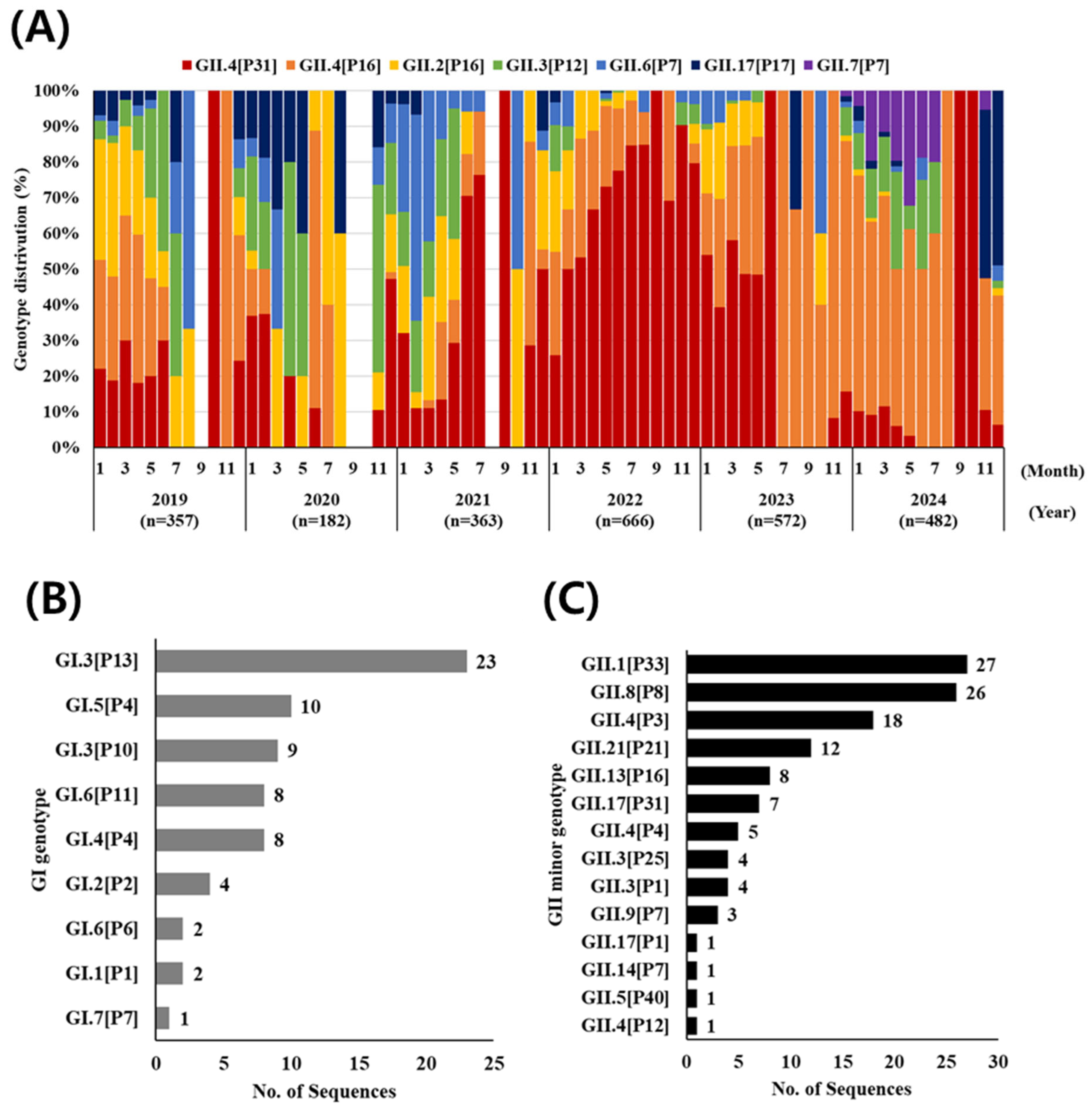

3.2. Norovirus Genotyping (G and P Type)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlson, K.B.; Dilley, A.; O’Grady, T.; Johnson, J.A.; Lopman, B.; Viscidi, E. A narrative review of norovirus epidemiology, biology, and challenges to vaccine development. npj Vaccines 2016, 7, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahmand, M.; Moghoofei, M.; Dorost, A.; Shoja, Z.; Ghorbani, S.; Kiani, S.J.; Khales, P.; Esteghamati, A.; Sayyahfar, S.; Jafarzadeh, M.; et al. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of norovirus infection in children with gastroenteritis: A meta-analysis on 6 years of research from 2015 to 2020. Rev. Med Virol. 2022, 3, e94–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.M.; Hall, A.J.; Vinjé, J.; Parashar, U.D. Noroviruses: A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopman, B.A.; Steele, D.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Parashar, U.D. The vast and varied global burden of norovirus: Prospects for prevention and control. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Lopman, B.A.; Payne, D.C.; Patel, M.M.; Gastanaduy, P.A.; Vinjé, J.; Parashar, U.D. Norovirus disease in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.; van Beek, J.; Koopmans, M. Human norovirus transmission and evolution in a changing world. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, S.K.; de Andrade, J.D.S.R.; Malta, F.C.; Fialho, A.M.; Mello, M.D.S.; Burlandy, F.M.; Fumian, T.M. Norovirus Epidemiology and Genotype Circulation during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil, 2019–2022. Pathogens 2024, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K. Caliciviridae: The Noroviruses. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 582–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.L.; Bonifacio, J.; Bucardo, F.; Buesa, J.; Bruggink, L.; Chan, M.C.W.; Fumian, T.M.; Giri, S.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Hewitt, J.; et al. Global Trends in Norovirus Genotype Distribution among Children with Acute Gastroenteritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; de Graaf, M.; Parra, G.I.; Chan, M.C.; Green, K.; Martella, V.; Wang, Q.; White, P.A.; Katayama, K.; Vennema, H.; et al. Updated classification of norovirus genogroups and genotypes. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenga, J.J.; Vennema, H.; Zheng, D.P.; Vinjé, J.; Lee, B.E.; Pang, X.L.; Ho, E.C.; Lim, W.; Choudekar, A.; Broor, S.; et al. Norovirus illness is a global problem: Emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001–2007. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.M.; Silva, L.D.; Sousa Junior, E.C.; Cardoso, J.F.; Reymão, T.K.A.; Portela, A.C.R.; de Lima, C.P.S.; Teixeira, D.M.; Lucena, M.S.S.; Nunes, M.R.T.; et al. Evolutionary and Molecular Analysis of Complete Genome Sequences of Norovirus from Brazil: Emerging Recombinant Strain GII.P16/GII.4. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroneman, A.; Vega, E.; Vennema, H.; Vinjé, J.; White, P.A.; Hansman, G.; Green, K.; Martella, V.; Katayama, K.; Koopmans, M. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 2059–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. CaliciNet Surveillance Network. CDC Norovirus (Reporting & Surveillance). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/php/reporting/calicinet.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Vega, E.; Barclay, L.; Gregoricus, N.; Williams, K.; Lee, D.; Vinjé, J. Novel surveillance network for norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroneman, A.; Vennema, H.; Deforche, K.; v d Avoort, H.; Penaranda, S.; Oberste, M.S.; Vinjé, J.; Koopmans, M. An automated genotyping tool for enteroviruses and noroviruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 51, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, J.S.; Tanaka, M.M.; Boni, M.F.; Rawlinson, W.D.; White, P.A. Recombination within the pandemic norovirus GII.4 lineage. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6270–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, J.; Armah, G.E.; Steele, A.D.; Taylor, M.B. Norovirus epidemiology in Africa: A review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, B.; He, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Bai, G. Epidemiological characteristics of norovirus infection in pediatric patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Ao, Y.; Jia, R.; Zhong, H.; Liu, P.; Xu, M.; Su, L.; Cao, L.; Xu, J. Changing predominance of norovirus strains in children with acute gastroenteritis in Shanghai, 2018–2021. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, M.; Lu, L.; Ma, A.; Cao, L.; Su, L.; Dong, N.; Jia, R.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J. The Changing Pattern of Common Respiratory and Enteric Viruses among Outpatient Children in Shanghai, China: Two Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 4696–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraay, A.N.M.; Han, P.; Kambhampati, A.; Wikswo, M.E.; Mirza, S.A.; Lopman, B.A. Impact of Nonpharmaceutical Interventions for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 on Norovirus Outbreaks: An Analysis of Outbreaks Reported By 9 US States. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Kageyama, T.; Fukushi, S.; Hoshino, F.B.; Shinohara, M.; Uchida, K.; Natori, K.; Takeda, N.; Katayama, K. Genogroup-specific PCR primers for detection of Norwalk-like viruses. J. Virol. Methods 2002, 100, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Jo, Y.; Park, S.-W.; Han, M.-G. Recent Trends in the Circulation of Viruses Causing Acute Gastroenteritis in the Republic of Korea, 2019–2023. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2024, 17, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-R.; Chae, S.-J.; Jung, S.; Choi, W.; Han, M.-G.; Yoo, C.-K.; Lee, D.-Y. Trends in acute viral gastroenteritis among children aged ≤5 years through the national surveillance system in South Korea, 2013–2019. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4875–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachamkin, I.; Richard-Greenblatt, M.; Yu, M.; Bui, H. Reduction in Sporadic Norovirus Infections Following the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2019–2020, Philadelphia. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, R.P.; Griffin, C.; Miller, E.L.; Dong, H.; Rabago, D.; Zgierska, A.E. Norovirus Infections Drop 49% in the United States with Strict COVID-19 Public Health Interventions. Acta Med. Acad. 2020, 49, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C. Return of Norovirus and Rotavirus Activity in Winter 2020–21 in City with Strict COVID-19 Control Strategy, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.; Faber, M.; Altmann, B.; Mas Marques, A.; Bock, C.T.; Niendorf, S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on norovirus circulation in Germany. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 314, 151600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmar, R.L.; Bernstein, D.I.; Lyon, G.M.; Treanor, J.J.; Al-Ibrahim, M.S.; Graham, D.Y.; Vinjé, J.; Jiang, X.; Gregoricus, N.; Frenck, R.W.; et al. Serological correlates of protection against a GII.4 norovirus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015, 22, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinjé, J. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, J.A.; Tohma, K.; Parra, G.I. Global and regional circulation trends of norovirus genotypes and recombinants, 1995–2019: A comprehensive review of sequences from public databases. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | No. of Samples—NoV Positive/Tested (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | |

| 0–5 | 530/2798 | 324/2258 | 637/3262 | 803/3463 | 721/3633 | 620/2877 | 3635/18,291 |

| (18.9) | (14.3) | (19.5) | (23.2) | (19.8) | (21.6) | (19.9) | |

| 6–15 | 98/951 | 74/874 | 169/1090 | 116/1083 | 149/1398 | 249/1347 | 855/6743 |

| (10.3) | (8.5) | (15.5) | (10.7) | (10.7) | (18.5) | (12.7) | |

| 16–59 | 120/2984 | 104/2360 | 108/2040 | 87/2474 | 147/2830 | 153/2682 | 719/15,370 |

| (4.0) | (4.4) | (5.3) | (3.5) | (5.2) | (5.7) | (4.7) | |

| 60< | 71/3482 | 54/3888 | 52/3714 | 32/4535 | 113/6025 | 121/5111 | 443/26,755 |

| (2.0) | (1.4) | (1.4) | (0.7) | (1.9) | (2.4) | (1.7) | |

| Total | 819/10,215 | 556/9380 | 966/10,106 | 1038/11,555 | 1130/13,886 | 1143/12,017 | 5652/67,159 |

| (8.0) | (5.9) | (9.6) | (9.0) | (8.1) | (9.5) | (8.4) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.; Cho, S.-R.; Jo, Y.; Lee, D.-Y.; Han, M.-G.; Park, S.-W. Trends in Norovirus Genotypes in South Korea, 2019–2024: Insights from Nationwide Dual Typing Surveillance. Viruses 2025, 17, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121572

Lee M, Cho S-R, Jo Y, Lee D-Y, Han M-G, Park S-W. Trends in Norovirus Genotypes in South Korea, 2019–2024: Insights from Nationwide Dual Typing Surveillance. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121572

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Minji, Seung-Rye Cho, Yunhee Jo, Deog-Yong Lee, Myung-Guk Han, and Sun-Whan Park. 2025. "Trends in Norovirus Genotypes in South Korea, 2019–2024: Insights from Nationwide Dual Typing Surveillance" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121572

APA StyleLee, M., Cho, S.-R., Jo, Y., Lee, D.-Y., Han, M.-G., & Park, S.-W. (2025). Trends in Norovirus Genotypes in South Korea, 2019–2024: Insights from Nationwide Dual Typing Surveillance. Viruses, 17(12), 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121572