Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro by Repurposing Clinically Approved Drugs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Labeled Proteins

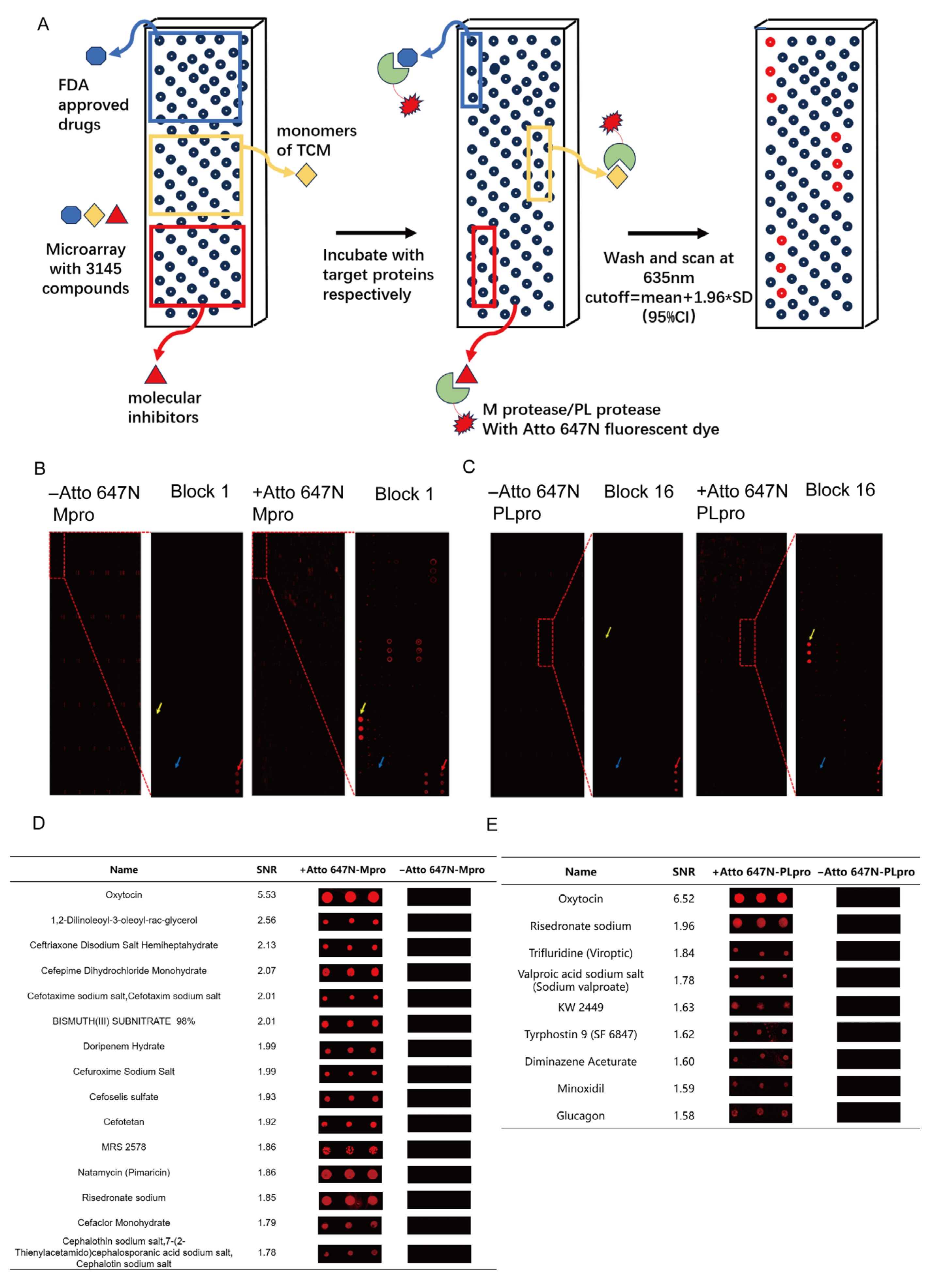

2.2. Small Molecule Microarray

2.3. Microarray Data Processing

2.4. SARS-CoV-2 PLpro and Mpro Enzymatic Assays

2.5. Protein Preparation for Molecular Docking

2.6. Ligand Preparation for Molecular Docking

2.7. Molecular Docking

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.9. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Pseudotyped Virus Detection

3. Results

3.1. Large-Scale Screening of Active Compounds Based on Small-Molecule Microarray

3.2. The Small Molecule Microarray Analysis for Drug Repurposing

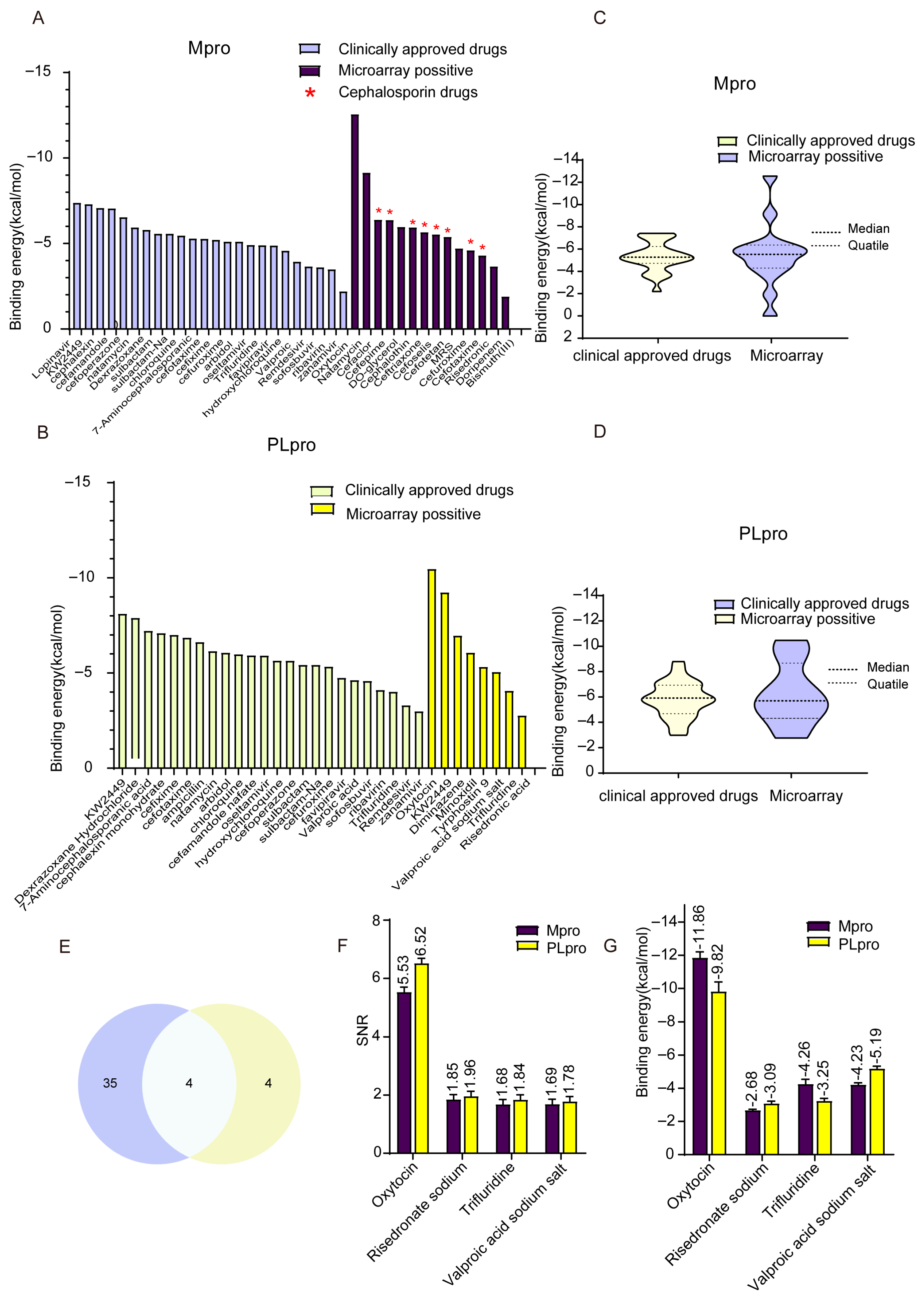

3.3. The Binding Energy Analysis of Active Compounds from Chip Screening

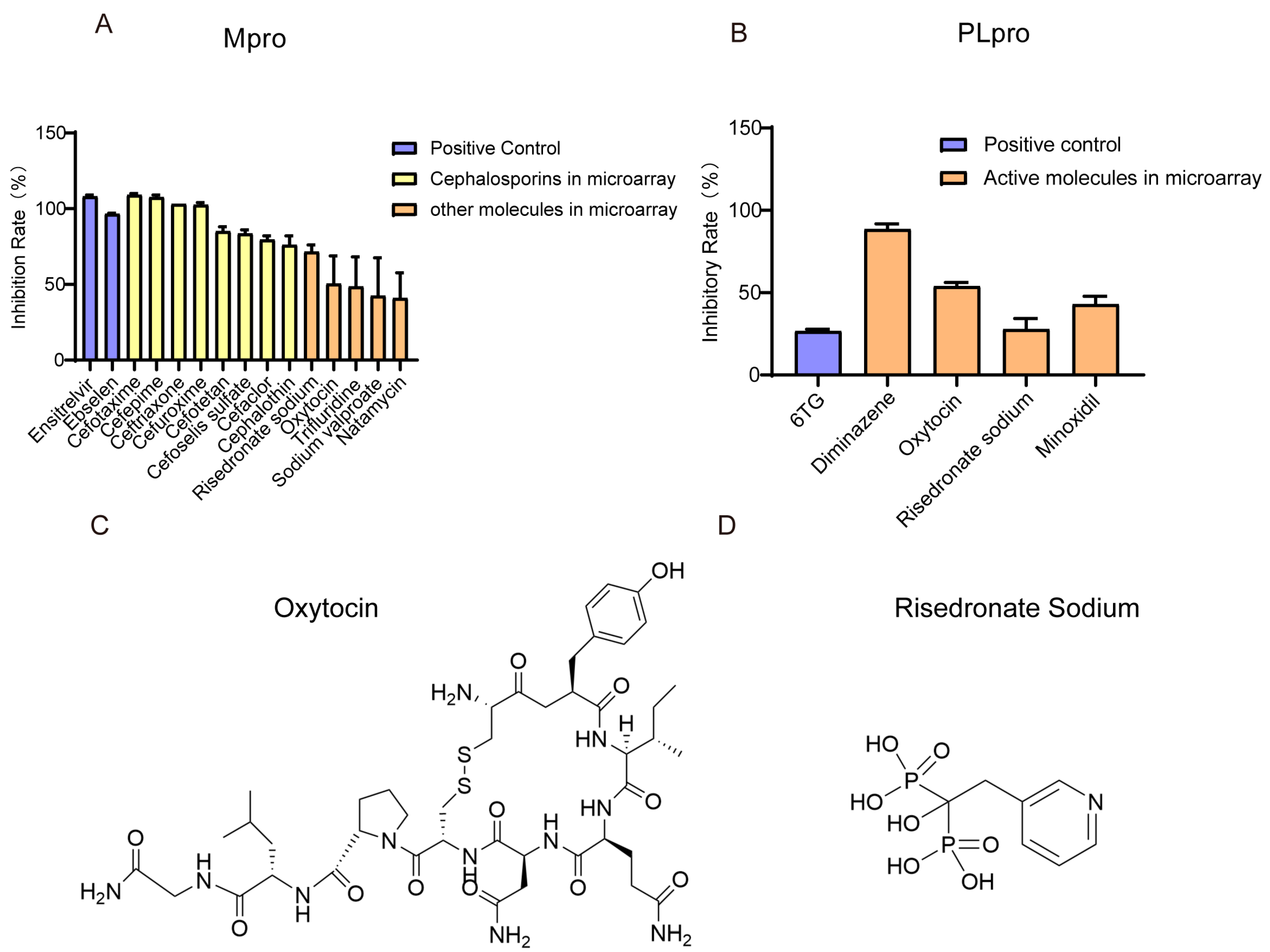

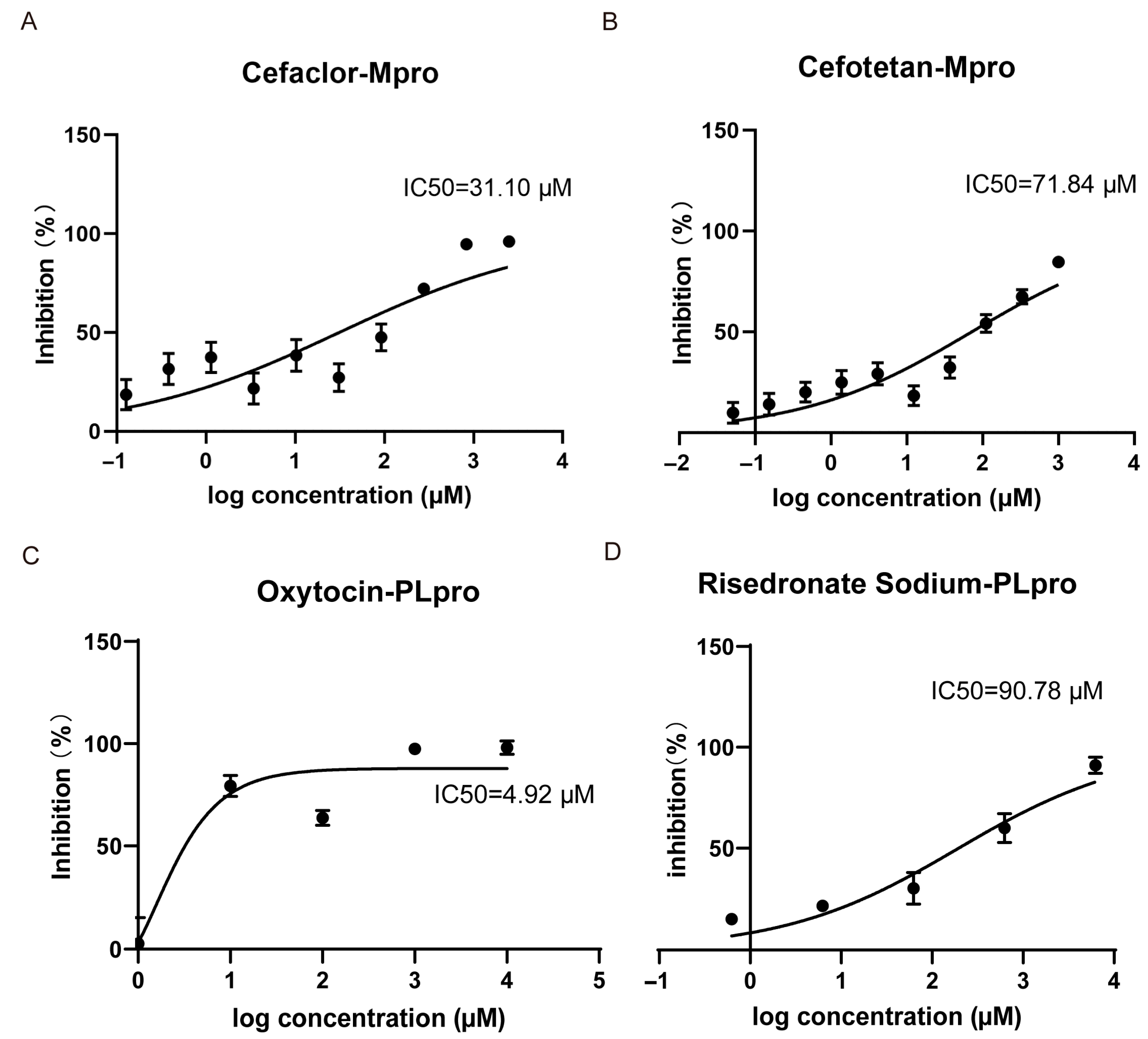

3.4. Small Molecules with Inhibitory Ability Against Mpro/PLpro Enzymes

3.5. The Inhibition Effect of Molecules on SARS-CoV-2 Spike Pseudotyped Virus

3.6. The Binding Model Simulation of Active Compounds with Mpro

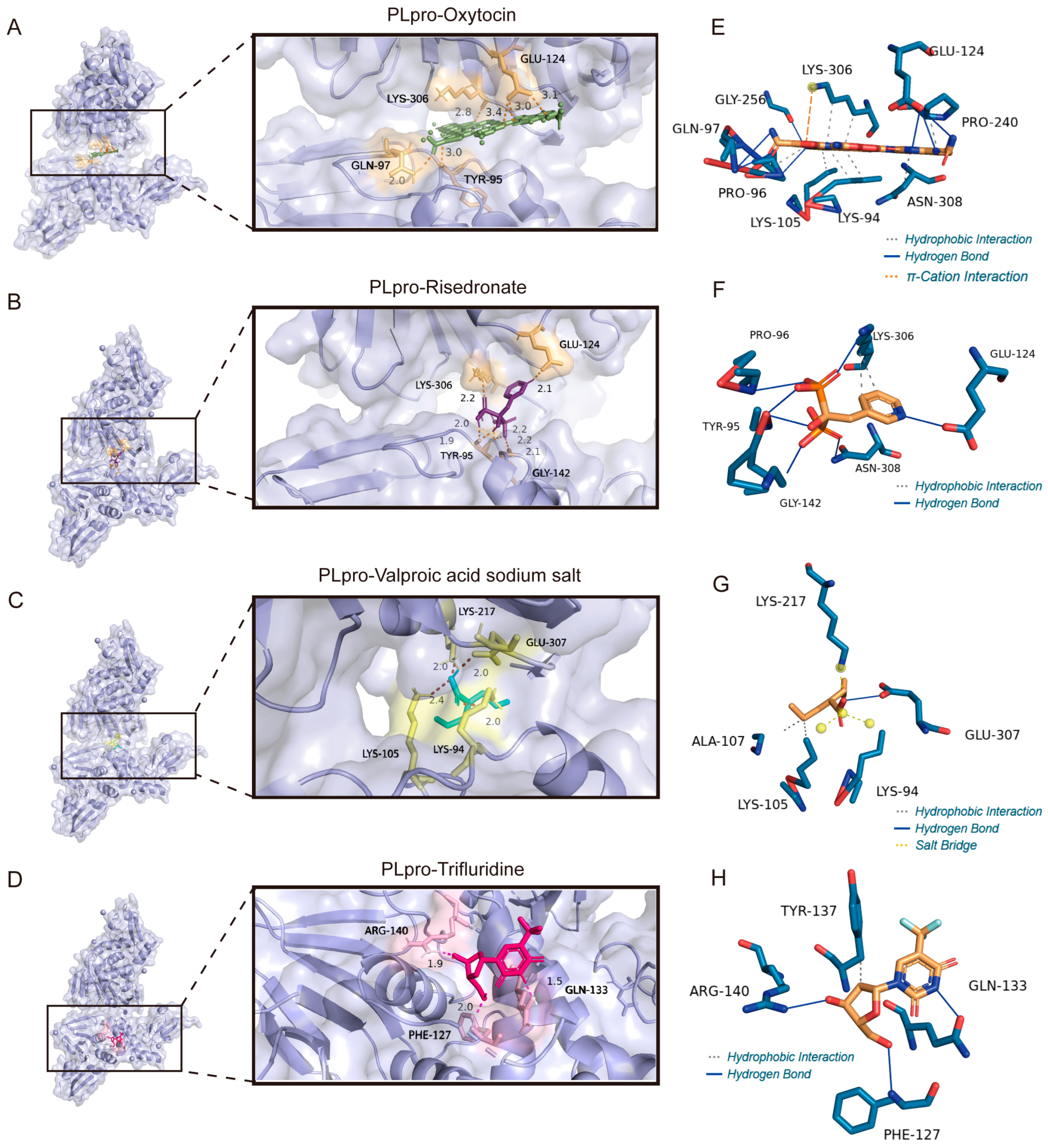

3.7. The Binding Model Simulation of Active Compounds with PLpro

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Mpro | Main protease |

| PLpro | Papain-Like protease |

| GSDMD | Gasdermin-D |

| ISG15 | Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 |

| NSP5 | Nonstructural protein 5 |

| NSP3 | Nonstructural protein 3 |

References

- Lubin, J.H.; Zardecki, C.; Dolan, E.M.; Lu, C.; Shen, Z.; Dutta, S.; Westbrook, J.D.; Hudson, B.P.; Goodsell, D.S.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 proteome in three dimensions (3D) during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Proteins 2022, 90, 1054–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Du, X.; Xu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, C.; et al. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 2020, 582, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Verschueren, K.H.; Anand, K.; Shen, J.; Yang, M.; Xu, Y.; Rao, Z.; Bigalke, J.; Heisen, B.; Mesters, J.R.; et al. pH-dependent conformational flexibility of the SARS-CoV main proteinase (M(pro)) dimer: Molecular dynamics simulations and multiple X-ray structure analyses. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Mukherjee, R.; Grewe, D.; Bojkova, D.; Baek, K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Schulz, L.; Widera, M.; Mehdipour, A.R.; Tascher, G.; et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 2020, 587, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Hu, Y.; Jadhav, P.; Tan, B.; Wang, J. Progress and Challenges in Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 7561–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rut, W.; Lv, Z.; Zmudzinski, M.; Patchett, S.; Nayak, D.; Snipas, S.J.; El Oualid, F.; Huang, T.T.; Bekes, M.; Drag, M.; et al. Activity profiling and crystal structures of inhibitor-bound SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease: A framework for anti-COVID-19 drug design. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabd4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Zhang, X.; Ansari, A.; Jadhav, P.; Tan, H.; Li, K.; Chopra, A.; Ford, A.; Chi, X.; Ruiz, F.X.; et al. Design of a SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease inhibitor with antiviral efficacy in a mouse model. Science 2024, 383, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Lee, M.K.; Gao, S.; Song, L.; Jang, H.Y.; Jo, I.; Yang, C.C.; Sylvester, K.; Ko, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Miniaturized Modular Click Chemistry-enabled Rapid Discovery of Unique SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors with Robust Potency and Drug-like Profile. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2404884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westberg, M.; Su, Y.; Zou, X.; Huang, P.; Rustagi, A.; Garhyan, J.; Patel, P.B.; Fernandez, D.; Wu, Y.; Hao, C.; et al. An orally bioavailable SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor exhibits improved affinity and reduced sensitivity to mutations. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadi0979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Ma, Q.; Kuzmič, P.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Jiang, H.; et al. Preclinical evaluation of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor RAY1216 shows improved pharmacokinetics compared with nirmatrelvir. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, T.R.; Tumber, A.; John, T.; Brewitz, L.; Strain-Damerell, C.; Owen, C.D.; Lukacik, P.; Chan, H.T.H.; Maheswaran, P.; Salah, E.; et al. Mass spectrometry reveals potential of beta-lactams as SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 1430–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielkopf, C.L.; Bauer, W.; Urbatsch, I.L. Bradford Assay for Determining Protein Concentration. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2020, 2020, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.; McDonnell, B.; Hearty, S.; Basabe-Desmonts, L.; Blue, R.; Trnavsky, M.; McAtamney, C.; O’Kennedy, R.; MacCraith, B.D. Novel disposable biochip platform employing supercritical angle fluorescence for enhanced fluorescence collection. Biomed. Microdevices 2011, 13, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Sha, T.; Ma, L.; Gao, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Allele-selective lowering of mutant HTT protein by HTT-LC3 linker compounds. Nature 2019, 575, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.M.; Abulwerdi, F.A.; Schneekloth, J.S., Jr. Discovery of RNA Binding Small Molecules Using Small Molecule Microarrays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1518, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradner, J.E.; McPherson, O.M.; Koehler, A.N. A method for the covalent capture and screening of diverse small molecules in a microarray format. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhu, X.; Landry, J.P.; Cui, Z.; Li, Q.; Dang, Y.; Mi, L.; Zheng, F.; Fei, Y. Developing an Efficient and General Strategy for Immobilization of Small Molecules onto Microarrays Using Isocyanate Chemistry. Sensors 2016, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Varbanov, M.; Philippot, S.; Vreken, F.; Zeng, W.B.; Blay, V. Ligand-based discovery of coronavirus main protease inhibitors using MACAW molecular embeddings. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittrich, S.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Chao, H.; Duarte, J.M.; Dutta, S.; Fayazi, M.; Henry, J.; Khokhriakov, I.; Lowe, R.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: Efficient Searching and Simultaneous Access to One Million Computed Structure Models Alongside the PDB Structures Enabled by Architectural Advances. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cheng, T.; He, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Li, Q.; Gindulyte, A.; Bolton, E.E. PubChem Protein, Gene, Pathway, and Taxonomy Data Collections: Bridging Biology and Chemistry through Target-Centric Views of PubChem Data. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huey, R.; Morris, G.M.; Olson, A.J.; Goodsell, D.S. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Fu, J.; Liang, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Y.; Han, S. Investigating interactions between chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine and their single enantiomers and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by a cell membrane chromatography method. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Han, S.; Liu, R.; Meng, L.; He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lv, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as ACE2 blockers to inhibit viropexis of 2019-nCoV Spike pseudotyped virus. Phytomedicine 2020, 79, 153333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, U. Computational Investigation of Selected Spike Protein Mutations in SARS-CoV-2: Delta, Omicron, and Some Circulating Subvariants. Pathogens 2023, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. What makes SARS-CoV-2 unique? Focusing on the spike protein. Cell Biol. Int. 2024, 48, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenko, M.; Onkhonova, G.; Susloparov, I.; Ryzhikov, A. SARS-CoV-2 proteins structural studies using synchrotron radiation. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, R.; Pathak, H.; Wang, X.; Jeong, G.H.; Kumari, P.; Kumar, M.; Yin, J. Ubiquitin Ligase Parkin Regulates the Stability of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease and Suppresses Viral Replication. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.T.; Song, W.Q.; Churilov, L.P.; Zhang, F.M.; Wang, Y.F. Psychophysical therapy and underlying neuroendocrine mechanisms for the rehabilitation of long COVID-19. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1120475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Parpura, V.; Wang, Y.F. Potential of Endogenous Oxytocin in Endocrine Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 799521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegay, K.B.; Adeyemi, C.M.; Gniffke, E.P.; Sather, D.N.; Walker, J.K.; Smith, S.E.P. A Repurposed Drug Screen Identifies Compounds That Inhibit the Binding of the COVID-19 Spike Protein to ACE2. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 685308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, P.T.; Talash, K.; Kasabri, V. Hypothesis: Oxytocin is a direct COVID-19 antiviral. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 145, 110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Shrivastava, R.; Shrivastava, V.K. Oxytocin as a Potential Adjuvant Against COVID-19 Infection. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumier, A.; Sirigu, A. Oxytocin as a potential defence against COVID-19? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 140, 109785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, P.T.; Chaudry, M.; Dixon, A.; Chaudry, F.; Kasabri, V. Oxytocin, the panacea for long-COVID? A review. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2022, 43, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryksa, K.; Neumann, I.D. Consequences of pandemic-associated social restrictions: Role of social support and the oxytocin system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 135, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Wang, Y.F. Cardiovascular protective properties of oxytocin against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2021, 270, 119130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buemann, B.; Marazziti, D.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Can intravenous oxytocin infusion counteract hyperinflammation in COVID-19 infected patients? World J. Biol. Psychiatry Off. J. World Fed. Soc. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 22, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y.; Yue, M.; Jiang, Y.; Qiu, D.; Yang, M.; et al. Micronanoparticled risedronate exhibits potent vaccine adjuvant effects. J. Control Release 2024, 365, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Zou, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F.; Xiong, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Risedronate-functionalized manganese-hydroxyapatite amorphous particles: A potent adjuvant for subunit vaccines and cancer immunotherapy. J. Control Release 2024, 367, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degli Esposti, L.; Perrone, V.; Sangiorgi, D.; Andretta, M.; Bartolini, F.; Cavaliere, A.; Ciaccia, A.; Dell’orco, S.; Grego, S.; Salzano, S.; et al. The Use of Oral Amino-Bisphosphonates and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outcomes. J. Bone Min. Res. 2021, 36, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, F.A.; Costa, G.; Romeo, I.; Esposito, F.; Alkhatib, M.; Salpini, R.; Svicher, V.; Corona, A.; Malune, P.; Tramontano, E.; et al. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: A Successful Story Guided by an In Silico Drug Repurposing Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 3601–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, F.; Zheng, H.; Yu, R. The study of antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike proteins through large-scale compound repurposing. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdonas, M.; Cerepenkaite, K.; Mickeviciute, A.; Kananaviciute, R.; Grybaite, B.; Anusevicius, K.; Ruksenaite, A.; Kojis, T.; Gedgaudas, M.; Mickevicius, V.; et al. Screening, Synthesis and Biochemical Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Protease Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.P.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Orian, L.; Bortoli, M.; Nogara, P.A. In silico studies of M(pro) and PL(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and a new class of cephalosporin drugs containing 1,2,4-thiadiazole. Struct. Chem. 2022, 33, 2205–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cui, J.; Chen, J.; Du, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, J.; Chen, H.; Wei, F.; Cai, Q.; et al. Identification of hACE2-interacting sites in SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain for antiviral drugs screening. Virus Res. 2022, 321, 198915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.R.; Bharadwaj, P.; Dingelstad, N.; Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Mandal, S.C.; Ganesan, A.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Palit, P. Structure-based virtual screening, molecular dynamics and binding affinity calculations of some potential phytocompounds against SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 6921–6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, R.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sawai, T. The effect of lipopolysaccharide on lipid bilayer permeability of beta-lactam antibiotics. FEBS Lett. 1984, 170, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jurek, B.; Neumann, I.D. The Oxytocin Receptor: From Intracellular Signaling to Behavior. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1805–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lu, J.; Xia, J. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3183–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Q.; Lu, M.; Chen, D.; Xie, L.; Hong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro by Repurposing Clinically Approved Drugs. Viruses 2025, 17, 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121564

Fang Q, Lu M, Chen D, Xie L, Hong W, Zhang Z, Hu X. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro by Repurposing Clinically Approved Drugs. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121564

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Qiaoyu, Meng Lu, Derong Chen, Liangxu Xie, Wenxu Hong, Zhang Zhang, and Xuqiao Hu. 2025. "Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro by Repurposing Clinically Approved Drugs" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121564

APA StyleFang, Q., Lu, M., Chen, D., Xie, L., Hong, W., Zhang, Z., & Hu, X. (2025). Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro by Repurposing Clinically Approved Drugs. Viruses, 17(12), 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121564