Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Coronavirus: A Review of Recent Advancements and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

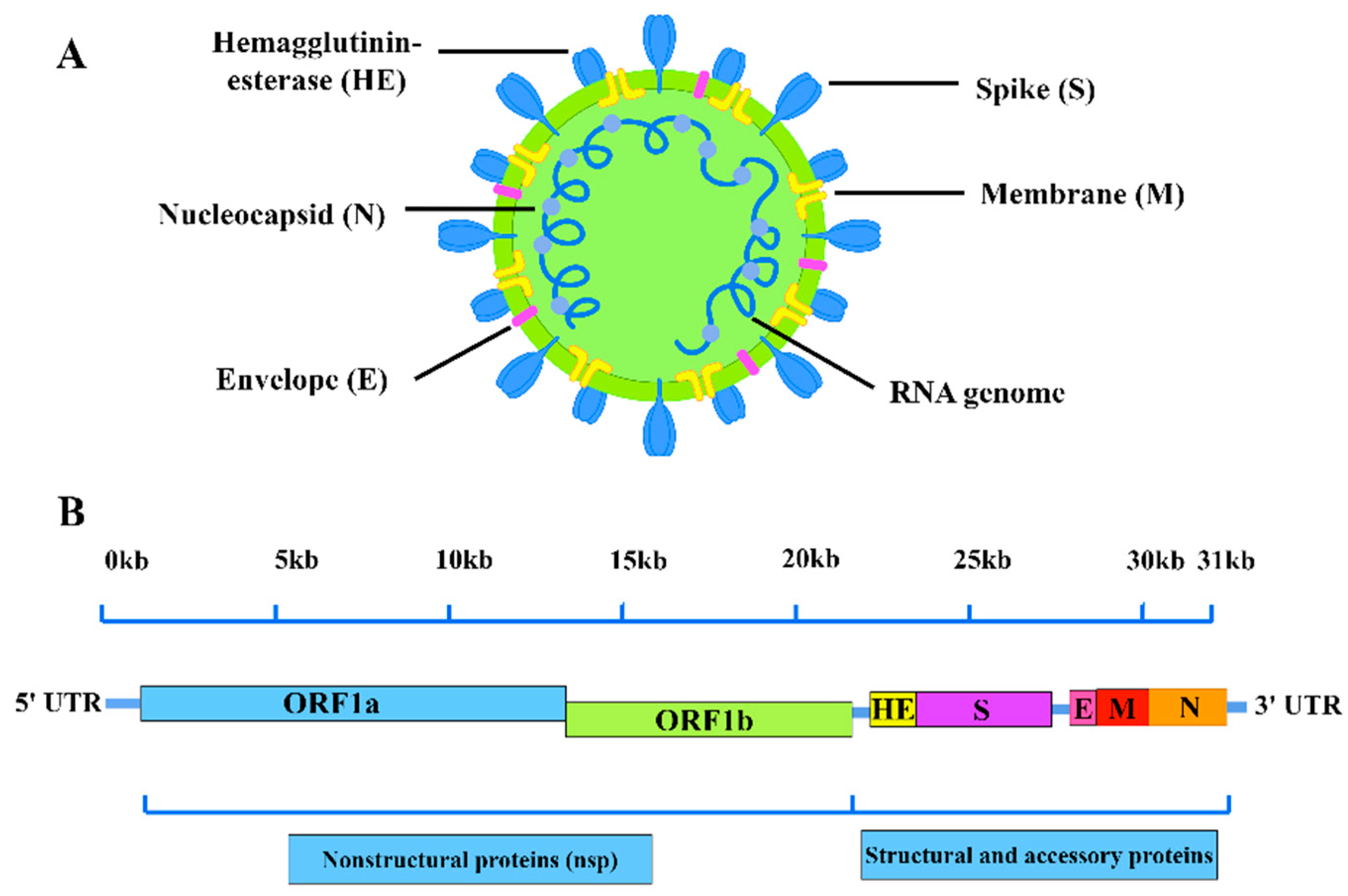

2. BCoVGenome Structure andIsolation Characteristics

3. Molecular Methods for Viral RNA Detection

3.1. Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

3.2. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

3.3. Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

3.4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

3.5. Isothermal Amplification

3.5.1. Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP)

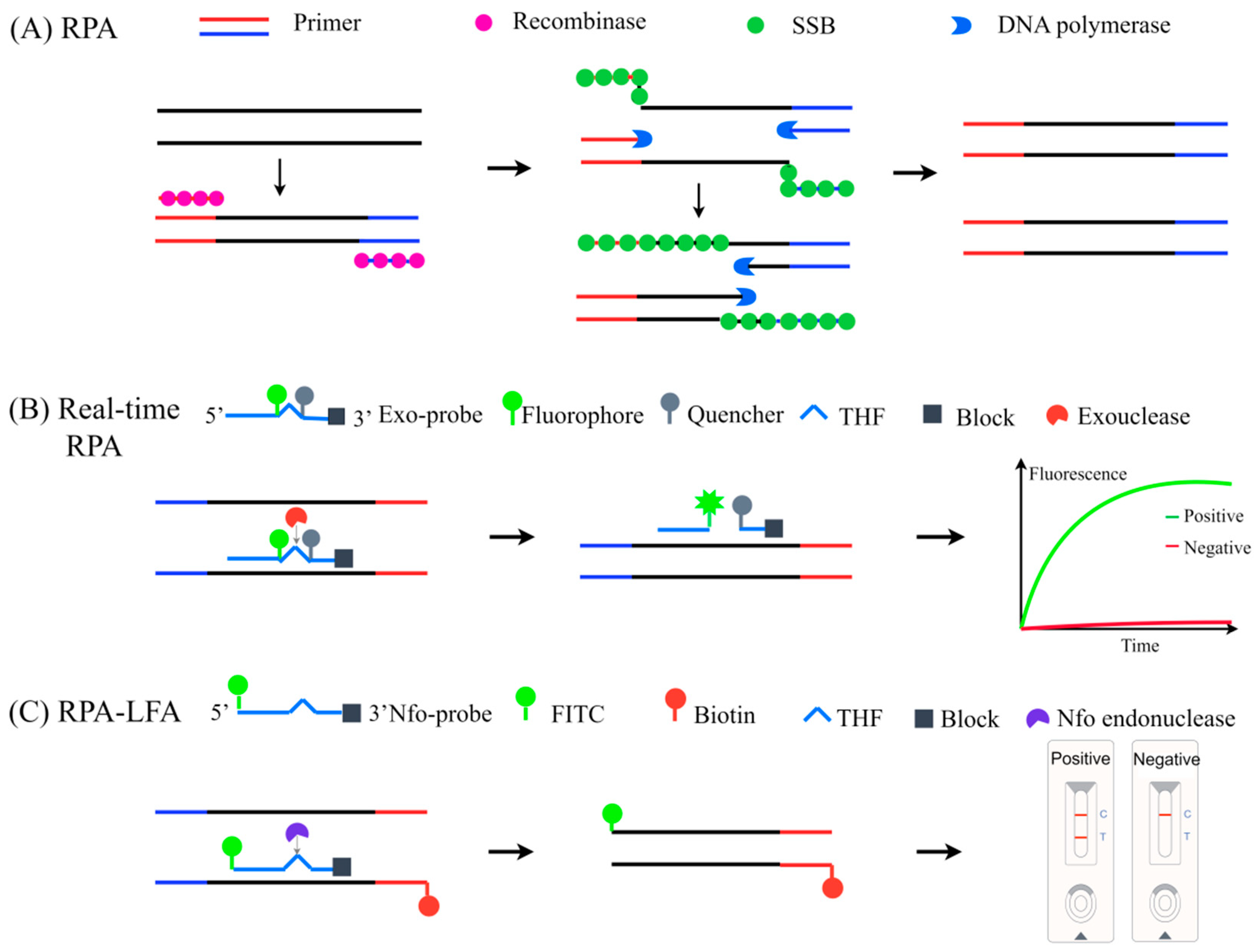

3.5.2. Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA)

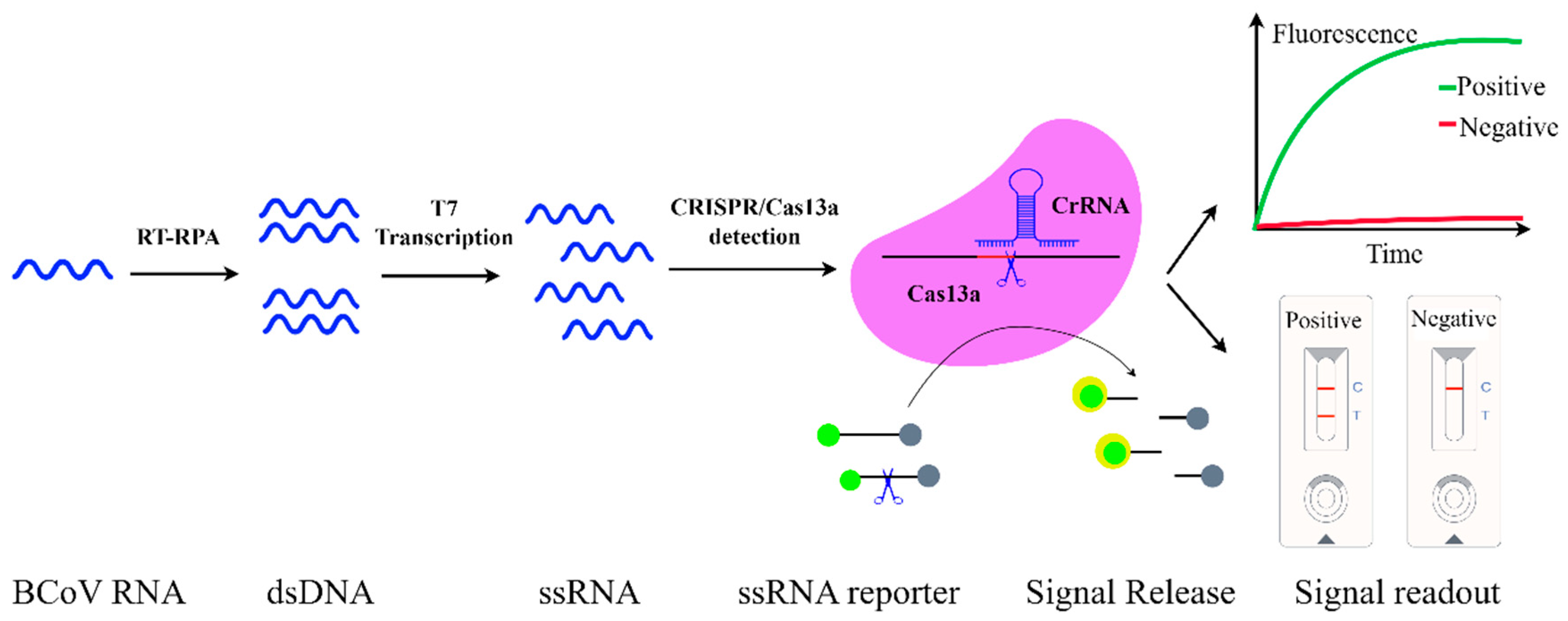

3.6. CRISPR/Cas13a Diagnostics

4. Immunological Methods for Antigen and Antibody Detection

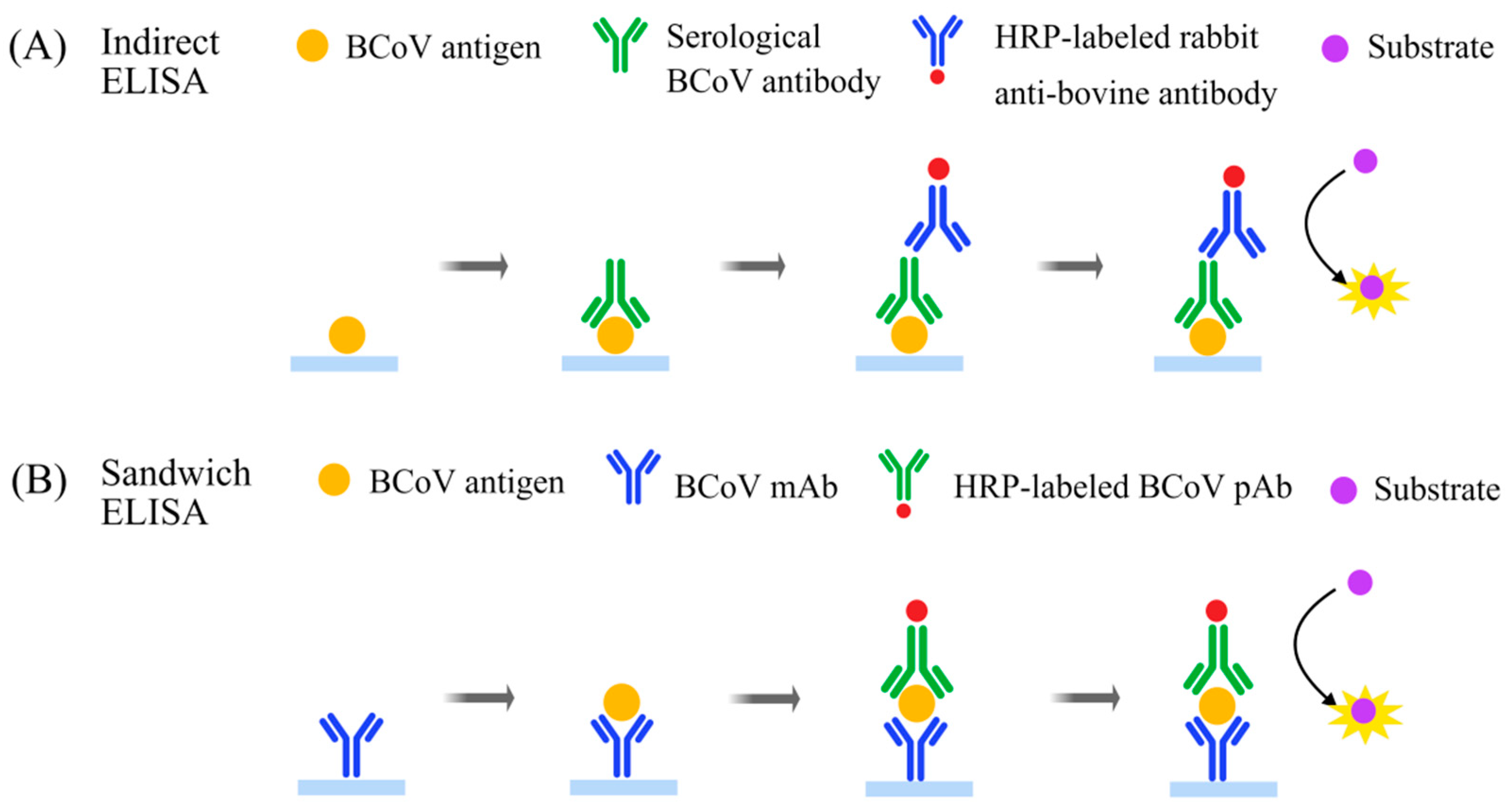

4.1. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.2. Serum Neutralization Test (SNT)

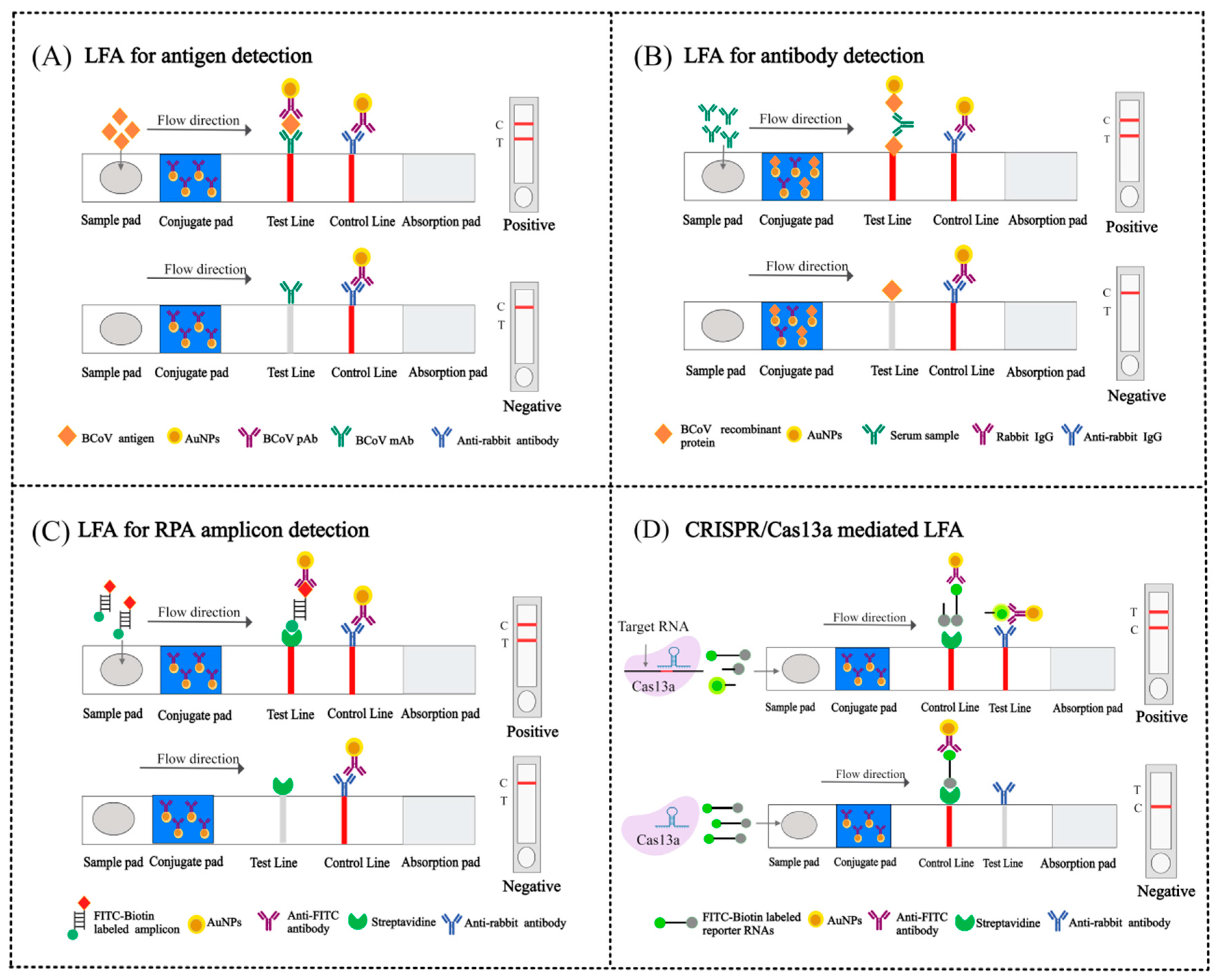

4.3. Lateral Flow Assay (LFA)

4.3.1. RT-LAMP-LFA

4.3.2. RPA-LFA

4.3.3. CRISPR/Cas13a-Based LFA

5. Future Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amoroso, M.G.; Lucifora, G.; Degli Uberti, B.; Serra, F.; De Luca, G.; Borriello, G.; De Domenico, A.; Brandi, S.; Cuomo, M.C.; Bove, F.; et al. Fatal Interstitial Pneumonia Associated with Bovine Coronavirus in Cows from Southern Italy. Viruses 2020, 12, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekata, H.; Hamabe, S.; Sudaryatma, P.E.; Kobayashi, I.; Kanno, T.; Okabayashi, T. Molecular epidemiological survey and phylogenetic analysis of bovine respiratory coronavirus in Japan from 2016 to 2018. J.Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molini, U.; Coetzee, L.M.; Hemberger, M.Y.; Jago, M.; Khaiseb, S.; Shapwa, K.; Lorusso, A.; Cattoli, G.; Dundon, W.G.; Franzo, G. Bovine coronavirus presence in domestic bovine and antelopes sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Namibia. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, A.C.; Vertenten, G. Bovine Coronavirus Prevalence and Risk Factors in Calves on Dairy Farms in Europe. Animals 2024, 14, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Lucente, M.S.; Cordisco, M.; Ciccarelli, S.; Di Fonte, R.; Sposato, A.; Mari, V.; Capozza, P.; Pellegrini, F.; Carelli, G.; et al. Natural Bovine Coronavirus Infection in a Calf Persistently Infected with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus: Viral Shedding, Immunological Features and S Gene Variations. Animals 2021, 11, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahkrajang, W.; Sudaryatma, P.E.; Mekata, H.; Hamabe, S.; Saito, A.; Okabayashi, T. Bovine respiratory coronavirus enhances bacterial adherence by upregulating expression of cellular receptors on bovine respiratory epithelial cells. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 255, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hurk, S.; Regmi, G.; Naikare, H.K.; Velayudhan, B.T. Advances in Laboratory Diagnosis of Coronavirus Infections in Cattle. Pathogens 2024, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, G.Y.; Choy, H.E.; Hong, Y.J.; Saif, L.J.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, S.I.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.K.; Shin, S.S.; et al. Dual enteric and respiratory tropisms of winter dysentery bovine coronavirus in calves. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 1885–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, L.J. Bovine Respiratory Coronavirus. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food. Anim. Pract. 2010, 26, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, M.J.; Kapil, S. Bovine Coronavirus Associated Syndromes. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food. Anim. Pract. 2010, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toftaker, I.; Holmøy, I.; Nødtvedt, A.; Østerås, O.; Stokstad, M. A cohort study of the effect of winter dysentery on herd-level milk production. J. Dairy. Sci. 2017, 100, 6483–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, N.; Ishihara, R.; Omiya, D.; Ishitsuka, M.; Hirano, S.; Suzuki, T. Application of a Photocatalyst as an Inactivator of Bovine Coronavirus. Viruses 2020, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, E.; Dhanasekaran, V.; Cassard, H.; Hause, B.; Maman, S.; Meyer, G.; Ducatez, M. Global Transmission, Spatial Segregation, and Recombination Determine the Long-Term Evolution and Epidemiology of Bovine Coronaviruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahe, M.C.; Magstadt, D.R.; Groeltz-Thrush, J.; Gauger, P.C.; Zhang, J.; Schwartz, K.J.; Siepker, C.L. Bovine coronavirus in the lower respiratory tract of cattle with respiratory disease. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2022, 34, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, H.M. Bovine-like coronaviruses in domestic and wild ruminants. Anim. Health. Res. Rev. 2019, 19, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Yoon, S.W.; Noh, J.Y.; Ahn, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, D.G.; Kim, H.K. Detection of bovine coronavirus in nasal swab of non-captive wild water deer, Korea. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Bovine Coronavirus and the Associated Diseases. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 643220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Meng, W.; Zeng, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; et al. Epidemiological survey of calf diarrhea related viruses in several areas of Guangdong Province. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1441419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Palomares, R.A.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Koo, C.; Granberry, F.; Locke, S.R.; Habing, G.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, L.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Contemporary Bovine Coronavirus Strains. Viruses 2024, 16, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Ghorr, A.A.; Snodgrass, D.R.; Scott, F.M. Evaluation of an immunogold electron microscopy technique for detecting bovine coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods 1988, 19, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.M.; Kapil, S.; Goyal, S.M. Comparison of immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and direct fluorescent antibody test for the detection of bovine coronavirus. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1998, 10, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; de Groot, R.J.; Haagmans, B.; Lau, S.K.P.; Neuman, B.W.; Perlman, S.; Sola, I.; van der Hoek, L.; Wong, A.C.P.; Yeh, S.H. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Coronaviridae 2023. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104, 001843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.U.; Gauger, P.; Hemida, M.G. Isolation and molecular characterization of an enteric isolate of the genotype-Ia bovine coronavirus with notable mutations in the receptor binding domain of the spike glycoprotein. Virology 2025, 603, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VilČEk, S.; JackovÁ, A.; KolesÁRovÁ, M.; VlasÁKovÁ, M. Genetic variability of the S1 subunit of enteric and respiratory bovine coronavirus isolates. Acta Virol. 2017, 61, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Koerhuis, D.; van den Burg, A.C.S.; Rozemuller, E.; Bosch, B.J.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Boons, G.J.; Huizinga, E.G.; et al. Coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase and spike proteins coevolve for functional balance and optimal virion avidity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25759–25770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keha, A.; Xue, L.; Yan, S.; Yue, H.; Tang, C. Prevalence of a novel bovine coronavirus strain with a recombinant hemagglutinin/esterase gene in dairy calves in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.L.; Heller, M.C.; Crossley, B.M.; Clothier, K.A.; Anderson, M.L.; Barnum, S.S.; Pusterla, N.; Rowe, J.D. Diarrhea outbreak associated with coronavirus infection in adult dairy goats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridpath, J.F.; Fulton, R.W.; Bauermann, F.V.; Falkenberg, S.M.; Welch, J.; Confer, A.W. Sequential exposure to bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine coronavirus results in increased respiratory disease lesions: Clinical, immunologic, pathologic, and immunohistochemical findings. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2020, 32, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, N.; Cernicchiaro, N.; Torres, S.; Li, F.; Hause, B.M. Metagenomic characterization of the virome associated with bovine respiratory disease in feedlot cattle identified novel viruses and suggests an etiologic role for influenza D virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanić, V.; Kunić, V.; Prišlin Šimac, M.; Lolić, M.; Sukalić, T.; Brnić, D. Comparative Insights into Acute Gastroenteritis in Cattle Caused by Bovine Rotavirus A and Bovine Coronavirus. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chen, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Shang, H.; Hao, Y.; Gao, P.; He, X.; Xu, X. Seroprevalence of five diarrhea-related pathogens in bovine herds of scattered households in Inner Mongolia, China between 2019 and 2022. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.M.; Kuehn, L.A.; McDaneld, T.G.; Clawson, M.L.; Loy, J.D. Longitudinal study of humoral immunity to bovine coronavirus, virus shedding, and treatment for bovine respiratory disease in pre-weaned beef calves. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebus, C.A.; Stair, E.L.; Rhodes, M.B.; Twiehaus, M.J. Pathology of neonatal calf diarrhea induced by a coronavirus-like agent. Vet. Pathol. 1973, 10, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemitsu, H.; Smith, D.R.; Saif, L.J. Experimental inoculation of adult dairy cows with bovine coronavirus and detection of coronavirus in feces by RT-PCR. Arch. Virol. 1999, 144, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.O.; Hasoksuz, M.; Nielsen, P.R.; Chang, K.O.; Lathrop, S.; Saif, L.J. Cross-protection studies between respiratory and calf diarrhea and winter dysentery coronavirus strains in calves and RT-PCR and nested PCR for their detection. Arch. Virol. 2001, 146, 2401–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, D.E.; Arroyo, L.G.; Poljak, Z.; Viel, L.; Weese, J.S. Detection of Bovine Coronavirus in Healthy and Diarrheic Dairy Calves. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 1884–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Dong, J.; Haga, T.; Goto, Y.; Sueyoshi, M. Rapid and sensitive detection of bovine coronavirus and group a bovine rotavirus from fecal samples by using one-step duplex RT-PCR assay. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2011, 73, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Kuga, K.; Miyazaki, A.; Suzuki, T.; Tasei, K.; Aita, T.; Mase, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Tsunemitsu, H. Development and application of one-step multiplex reverse transcription PCR for simultaneous detection of five diarrheal viruses in adult cattle. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, B.; Marwaha, S.; Minakshi, P.; Ikbal; Ranjan, K.; Misri, J. A Rapid and Novel Multiplex PCR Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Multiple Viruses Associated with Bovine Gastroenteritis. Indian. J. Microbiol. 2023, 63, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loa, C.C.; Lin, T.L.; Wu, C.C.; Bryan, T.A.; Hooper, T.A.; Schrader, D.L. Differential detection of turkey coronavirus, infectious bronchitis virus, and bovine coronavirus by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 131, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso, N.H.; Silva Junior, J.V.J.; Becker, A.S.; Weiblen, R.; Flores, E.F. An end-point multiplex PCR/reverse transcription-PCR for detection of five agents of bovine neonatal diarrhea. J. Microbiol. Methods 2023, 209, 106738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, T.; Song, D.; Huang, T.; Peng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, A.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Q.; Ye, Y.; et al. Comparison and evaluation of conventional RT-PCR, SYBR green I and TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assays for the detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Mol. Cell. Probes 2017, 33, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, H.M.; Almajhdi, F.N. Development of a SYBR Green I based real-time RT-PCR assay for detection and quantification of bovine coronavirus. Mol. Cell. Probes 2011, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Desario, C.; Mari, V.; Radogna, A.; Colaianni, M.L.; Cirone, F.; Tempesta, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Detection of bovine coronavirus using a TaqMan-based real-time RT-PCR assay. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 151, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholm, J.; Tessema, T.S.; Blomström, A.-L.; Berg, M. Detection and molecular characterization of major enteric pathogens in calves in central Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiaka, S.; Masuda, T.; Sugimura, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Komatsu, N.; Nagai, M.; Omatsu, T.; Furuya, T.; Oba, M.; Katayama, Y.; et al. Development of a novel detection system for microbes from bovine diarrhea by real-time PCR. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.I.; Kim, W.I.; Liu, S.; Kinyon, J.M.; Yoon, K.J. Development of a panel of multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for simultaneous detection of major agents causing calf diarrhea in feces. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010, 22, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Chang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, M.; Jing, B.; Zhao, A.; Yin, X. Development and application of one-step multiplex Real-Time PCR for detection of three main pathogens associated with bovine neonatal diarrhea. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1367385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yin, D.; Gao, H.; Li, H.; Fu, K.; Cao, Z. Multiplex one-step RT–qPCR assays for simultaneous detection of BRV, BCoV, Escherichia coli K99+ and Cryptosporidium parvum. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1561533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Ma, Z.; Jia, K.; Li, S. A multiplex real-time fluorescence-based quantitative PCR assay for calf diarrhea viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1327291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Niu, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, Q.; Gong, Z.; Wei, S. Triplex qRT-PCR with specific probe for synchronously detecting Bovine parvovirus, bovine coronavirus, bovine parainfluenza virus and its applications. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 23, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansri, P.; Katholm, J.; Krogh, K.M.; Aagaard, A.K.; Schmidt, L.M.B.; Kudirkiene, E.; Larsen, L.E.; Olsen, J.E. Evaluation of novel multiplex qPCR assays for diagnosis of pathogens associated with the bovine respiratory disease complex. Vet. J. 2020, 256, 105425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Fukunari, K.; Suzuki, T. Multiplex RT-qPCR Application in Early Detection of Bovine Respiratory Disease in Healthy Calves. Viruses 2023, 15, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Digital PCR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 9236–9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, P.-L.; Sauzade, M.; Brouzes, E. dPCR: A Technology Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, D.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fu, Q.; Shi, H. Establishment and application of multiplex droplet digital polymerase chain reaction assay for bovine enterovirus, bovine coronavirus, and bovine rotavirus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1157900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-C.; Kim, Y.; Cho, Y.-I.; Park, J.; Choi, K.-S. Evaluation of bovine coronavirus in Korean native calves challenged through different inoculation routes. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharieva, M.M.; Foka, P.; Karamichali, E.; Kroumov, A.D.; Philipov, S.; Ilieva, Y.; Kim, T.C.; Podlesniy, P.; Manasiev, Y.; Kussovski, V.; et al. Photodynamic Inactivation of Bovine Coronavirus with the Photosensitizer Toluidine Blue O. Viruses 2023, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oma, V.S.; Klem, T.; Tråvén, M.; Alenius, S.; Gjerset, B.; Myrmel, M.; Stokstad, M. Temporary carriage of bovine coronavirus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus by fomites and human nasal mucosa after exposure to infected calves. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Huang, J.; Cai, X.; Mao, L.; Xie, L.; Wang, F.; Zhou, H.; Yuan, X.; Sun, X.; Fu, X.; et al. Prevalence and Evolutionary Characteristics of Bovine Coronavirus in China. Vet. Res. 2024, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.; Shah, A.U.; Duraisamy, N.; ElAlaoui, R.N.; Cherkaoui, M.; Hemida, M.G. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Gene Expression Analysis to Identify Some Potential Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV) Receptors and Host Cell Enzymes Potentially Involved in the Viral Replication and Tissue Tropism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Meng, Q.; Cai, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Z. Rapid detection of Betacoronavirus 1 from clinical fecal specimens by a novel reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. J. Vet. Investig. 2012, 24, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Mi, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Rapid and Sensitive Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Combined with Lateral Flow Strip for Detecting African Swine Fever Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, A.; Cheng, Y. Establishment and application of a rapid diagnostic method for BVDV and IBRV using recombinase polymerase amplification-lateral flow device. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1360504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, H.; Hou, P.; Xia, X.; He, H. A lateral flow dipstick combined with reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification for rapid and visual detection of the bovine respirovirus 3. Mol. Cell. Probes 2018, 41, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Z.; Fang, D.Z.; Chen, F.F.; Zhao, Q.F.; Cai, C.M.; Cheng, M.G. Utilization of recombinase polymerase amplification method combined with lateral flow dipstick for visual detection of respiratory syncytial virus. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 49, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, D.S.; Guimaraes, J.M.; Gandarilla, A.M.D.; Filho, J.; Brito, W.R.; Mariuba, L.A.M. Recombinase polymerase amplification in the molecular diagnosis of microbiological targets and its applications. Can. J. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, L.; Ma, R.; Cong, L.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Xue, S.; Zheng, W.; Tang, S. Rapid detection of Salmonella with Recombinase Aided Amplification. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 139, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, N.; Zhao, C.; Xia, W. Recombinase Polymerase Amplification-Based Biosensors for Rapid Zoonoses Screening. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 6311–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhu, S.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Ren, C.; Zhu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Z. Establishment of a Real-Time Reverse Transcription Recombinase-Aided Isothermal Amplification (qRT-RAA) Assay for the Rapid Detection of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Vet. Res. 2024, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Wang, W.; Guo, Z.; Yin, W.; Cheng, M.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Hu, Y.; et al. Rapid visual detection of hepatitis E virus combining reverse transcription recombinase-aided amplification with lateral flow dipstick and real-time fluorescence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-Z.; Chen, J.-T.; Li, J.; Wu, X.-J.; Wen, J.-Z.; Liu, X.-Z.; Lin, L.-Y.; Liang, X.-Y.; Huang, H.-Y.; Zha, G.-C.; et al. Reverse Transcription Recombinase-Aided Amplification Assay With Lateral Flow Dipstick Assay for Rapid Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 613304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, M.A. Critical insight into recombinase polymerase amplification technology. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, H.M.; Abd El Wahed, A.; Shalaby, M.A.; Almajhdi, F.N.; Hufert, F.T.; Weidmann, M. A new approach for diagnosis of bovine coronavirus using a reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification assay. J. Virol. Methods 2013, 193, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Pan, Y.; Wu, C.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Bai, H.; Gong, Y.; Liu, J.; Tao, L.; et al. Development of Rapid Isothermal Detection Methods Real-Time Fluorescence and Lateral Flow Reverse Transcription Recombinase-Aided Amplification Assay for Bovine Coronavirus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2024, 2024, 7108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Shan, Y.; Li, X.; Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xie, R.; Zhao, L. Development of a duplex real-time recombinase aided amplification assay for the simultaneous and rapid detection of PCV3 and PCV4. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Herbst, W.; Kousoulas, K.G.; Storz, J. Biological and genetic characterization of a hemagglutinating coronavirus isolated from a diarrhoeic child. J. Med. Virol. 1994, 44, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chertow, D.S. Next-generation diagnostics with CRISPR. Science 2018, 360, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Iranzo, J.; Shmakov, S.A.; Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Charpentier, E.; Cheng, D.; Haft, D.H.; Horvath, P.; et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems: A burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 18, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Lee, J.W.; Essletzbichler, P.; Dy, A.J.; Joung, J.; Verdine, V.; Donghia, N.; Daringer, N.M.; Freije, C.A.; et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 2017, 356, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Konermann, S.; Joung, J.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Cox, D.B.T.; Shmakov, S.; Makarova, K.S.; Semenova, E.; Minakhin, L.; et al. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 2016, 353, aaf5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Luo, R.; He, Q.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Specific and sensitive detection of bovine coronavirus using CRISPR-Cas13a combined with RT-RAA technology. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1473674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khudhair, Y.I.; Alsultan, A.; Hussain, M.H.; Ayez, F.J. Novel CRISPR/Cas13-based assay for detection of bovine coronavirus associated with severe diarrhea in calves. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayrapetyan, H.; Tran, T.; Tellez-Corrales, E.; Madiraju, C. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay: Types and Applications. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2023, 2612, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenthaler, S.L.; Kapil, S. Development and applications of a bovine coronavirus antigen detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1999, 6, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschová, S.; Pokorová, D.; Nevoránková, Z.; Franz, J. Monoclonal antibodies to bovine coronavirus and their use in enzymoimmunoanalysis and immunochromatography. Vet. Med. 2001, 46, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, K.; Traven, M.; Larsson, B.; Silvan, A.; Linde, N. Capture ELISA systems for the detection of bovine coronavirus-specific IgA and IgM antibodies in milk and serum. Vet. Microbiol. 2000, 72, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toftaker, I.; Toft, N.; Stokstad, M.; Sølverød, L.; Harkiss, G.; Watt, N.; O’ Brien, A.; Nødtvedt, A. Evaluation of a multiplex immunoassay for bovine respiratory syncytial virus and bovine coronavirus antibodies in bulk tank milk against two indirect ELISAs using latent class analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 154, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Niu, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Gao, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Establishment of an indirect ELISA method for detecting bovine coronavirus antibodies based on N protein. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1530870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Iovane, V.; Improda, E.; Iovane, G.; Pagnini, U.; Montagnaro, S. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors for Bovine Coronavirus Infection among Dairy Cattle and Water Buffalo in Campania Region, Southern Italy. Animals 2023, 13, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Mari, V.; Desario, C.; Lucente, M.S.; Lorusso, A.; Greco, G.; Corrente, M.; et al. Biological and genetic analysis of a bovine-like coronavirus isolated from water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) calves. Virology 2008, 370, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burimuah, V.; Sylverken, A.; Owusu, M.; El-Duah, P.; Yeboah, R.; Lamptey, J.; Frimpong, Y.O.; Agbenyega, O.; Folitse, R.; Emikpe, B.; et al. Molecular-based cross-species evaluation of bovine coronavirus infection in cattle, sheep and goats in Ghana. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasoksuz, M.; Alekseev, K.; Vlasova, A.; Zhang, X.; Spiro, D.; Halpin, R.; Wang, S.; Ghedin, E.; Saif, L.J. Biologic, antigenic, and full-length genomic characterization of a bovine-like coronavirus isolated from a giraffe. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4981–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniiappa, L.; Mitov, B.K.; Kharalambiev Kh, E. Demonstration of coronavirus infection in buffaloes. Vet. Med. Nauki 1985, 22, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bok, M.; Mino, S.; Rodriguez, D.; Badaracco, A.; Nunes, I.; Souza, S.P.; Bilbao, G.; Louge Uriarte, E.; Galarza, R.; Vega, C.; et al. Molecular and antigenic characterization of bovine Coronavirus circulating in Argentinean cattle during 1994–2010. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 181, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemitsu, H.; el-Kanawati, Z.R.; Smith, D.R.; Reed, H.H.; Saif, L.J. Isolation of coronaviruses antigenically indistinguishable from bovine coronavirus from wild ruminants with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 3264–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, N.E.N.; Lacoste, S.; Sniatynski, M.; Waldner, C.; Ellis, J. Comparison of virus-neutralizing and virus-specific ELISA antibody responses among bovine neonates differentially primed and boosted against bovine coronavirus. Can. Vet. J. 2024, 65, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ye, C.; Cao, J.; Zhou, X.; Xie, M.; Qing, J.; Chen, Z. Application of recombinase polymerase amplification with lateral flow assay to pathogen point-of-care diagnosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1475922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. Lateral flow immunoassay for proteins. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 544, 117337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczula, K.M.; Gallotta, A. Lateral flow assays. Essays. Biochem. 2016, 60, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ince, B.; Sezgintürk, M.K. Lateral flow assays for viruses diagnosis: Up-to-date technology and future prospects. Trends. Analyt. Chem. 2022, 157, 116725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma-Trumpie, G.A.; Korf, J.; van Amerongen, A. Lateral flow (immuno)assay: Its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. A literature survey. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 393, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Kim, H.Y.; Oh, M.H.; Kim, Y.R. Paper-based lateral flow strip assay for the detection of foodborne pathogens: Principles, applications, technological challenges and opportunities. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-González, D.; Merkoçi, A. Nanomaterial-based devices for point-of-care diagnostic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4697–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytzka, N.; Arbaciauskaite, S.; Sandetskaya, N.; Mattern, K.; Kuhlmeier, D. A fully integrated duplex RT-LAMP device for the detection of viral infections. Biomed. Microdevices 2023, 25, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, C.; Feng, Y.; Sun, R.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Pan, Z.; Yao, H. Development of a multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification and lateral flow dipstick combination assay for bovine coronavirus detection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 9, 1059934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, J.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Xing, G.; Deng, R.; Zhang, G. An Isothermal Molecular Point of Care Testing for African Swine Fever Virus Using Recombinase-Aided Amplification and Lateral Flow Assay Without the Need to Extract Nucleic Acids in Blood. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 633763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wang, F.; Cui, Y.; Li, Z.; Lin, J. Innovative strategies for enhancing AuNP-based point-of-care diagnostics: Focus on coronavirus detection. Talanta 2025, 285, 127362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Liao, C.; Liang, L.; Yi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, G. Recent advances in recombinase polymerase amplification: Principle, advantages, disadvantages and applications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1019071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Jiao, J.; Mo, T. Combination of nucleic acid amplification and CRISPR/Cas technology in pathogen detection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1355234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X. Development of CRISPR-Mediated Nucleic Acid Detection Technologies and Their Applications in the Livestock Industry. Genes 2022, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, R.; Poddar, A.; Sonnaila, S.; Bhavaraju, V.S.M.; Agrawal, S. Advancing CRISPR-Based Solutions for COVID-19 Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Cells 2024, 13, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghouneimy, A.; Mahas, A.; Marsic, T.; Aman, R.; Mahfouz, M. CRISPR-Based Diagnostics: Challenges and Potential Solutions toward Point-of-Care Applications. ACS. Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, J.E.; Berendsen, J.T.W.; Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Wolthuis, R.M.F.; Eijkel, J.C.T.; Segerink, L.I. Point-of-care CRISPR/Cas nucleic acid detection: Recent advances, challenges and opportunities. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 166, 112445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumford, E.A.; Lu, J.; Spaczai, I.; Prasetyo, M.E.; Zheng, E.M.; Zhang, H.; Kamei, D.T. Developments in integrating nucleic acid isothermal amplification and detection systems for point-of-care diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 170, 112674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, X.; Yao, X.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. Lateral flow assay of pathogenic viruses and bacteria in healthcare. Analyst 2023, 148, 4573–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Upadhyay, D.J.; Srivastava, A. Next-Generation Molecular Diagnostics Development by CRISPR/Cas Tool: Rapid Detection and Surveillance of Viral Disease Outbreaks. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 582499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, A.F.; Barra, M.J.; Novak, E.N.; Bond, M.; Richards-Kortum, R. Point-of-care isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests: Progress and bottlenecks for extraction-free sample collection and preparation. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2024, 24, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, C.M.; Myhrvold, C.; Thakku, S.G.; Freije, C.A.; Metsky, H.C.; Yang, D.K.; Ye, S.H.; Boehm, C.K.; Kosoko-Thoroddsen, T.F.; Kehe, J.; et al. Massively multiplexed nucleic acid detection with Cas13. Nature 2020, 582, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafian, F.; Nafian, S.; Kamali Doust Azad, B.; Hashemi, M. CRISPR-Based Diagnostics and Microfluidics for COVID-19 Point-of-Care Testing: A Review of Main Applications. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Detection Method | Target | Detection Time | Limit of Detection | Technical Advantages and Limitations | Applicability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | N gene | 4–6 h | 200 RNA copies/reaction | High standardization; Multiplex capability; Thermal cycler required | Laboratory | [34] |

| qRT-PCR | M gene | 2–3 h | 20 RNA Copies/reaction | High standardization; Multiplex capability; Thermal cycle required | Laboratory | [44] |

| ddPCR | N gene | 3–4 h | 0.048 RNA copies/μL | Reference sensitivity; Absolute quantification; High reagent cost | Laboratory | [57] |

| RT-LAMP | N gene | 50 min | 100 RNA copies/reaction | Inhibitor tolerance; 4–6 primers per target; Constant temperature | Laboratory | [62] |

| Real-time RPA | N gene | 10–30 min | 19 RNA copies/reaction | Rapid amplification (37–42 °C); No thermal cycling; non-specificity amplification risk | laboratory | [74] |

| RPA-CRISPR- Fluorescence Assay | N gene | 30 min | 1.73 RNA copies/μL | Enhanced Sensitivity and Specificity; High reagent cost | Laboratory | [82] |

| RT-LAMP-LFA | N gene | 50–60 min | 100 RNA copies/reaction | Minimal equipment; Lyophilized reagents; Field-compatible | Field | [105] |

| RPA-LFA | N gene | 40 min | 146 RNA copies/μL | Rapid field protocol; Ambient-temperature storage | Field | [75] |

| RPA-CRISPR-LFA | M gene | 40 min | 10 RNA copies/μL | High sensitivity; Visual readout; Matrix interference resistance | Field | [83] |

| ELISA | N protein | 2–4 h | 1.25 μg/mL | High-throughput screening; Serum/fecal specimen compatibility | Laboratory | [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; He, X.; Bao, S.; Wei, Z. Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Coronavirus: A Review of Recent Advancements and Challenges. Viruses 2025, 17, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121533

Dong J, He X, Bao S, Wei Z. Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Coronavirus: A Review of Recent Advancements and Challenges. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121533

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jie, Xiaoxiao He, Shijun Bao, and Zhanyong Wei. 2025. "Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Coronavirus: A Review of Recent Advancements and Challenges" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121533

APA StyleDong, J., He, X., Bao, S., & Wei, Z. (2025). Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Coronavirus: A Review of Recent Advancements and Challenges. Viruses, 17(12), 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121533