Pasteurized Milk Serves as a Passive Surveillance Tool for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Dairy Cattle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Procurement

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction and RNA Purification from Milk Samples

2.3. Real-Time RT-PCR Detection of Influenza a Virus

2.4. Real-Time RT-PCR Detection of H5

2.5. Whole-Genome Amplification and Sequencing

2.6. Genomic Assembly and Phylogenetic Analysis of Whole-Genome Sequences

2.7. Variant Normalization and Annotation

2.8. Amplification and Sanger Sequencing of H5 Gene

3. Results

3.1. Influenza a Viral RNA Detection in Pasteurized Dairy Milk

- Brand G (Plant 2): Positive samples persisted up to 18 weeks before testing negative.

- Brand K (Plants 3 and 5): Initial samples were positive through week 3, then consistently negative.

- Brand AO (Plant 8): Samples remained positive until week 8; no further samples were available.

- Brand A (Plant 8): Positive through week 10 before transitioning to negative, enabling follow-up from Plant 8.

3.2. Influenza a Virus Whole-Genome Sequencing from Retail Milk

3.2.1. Sequencing Depth and Coverage

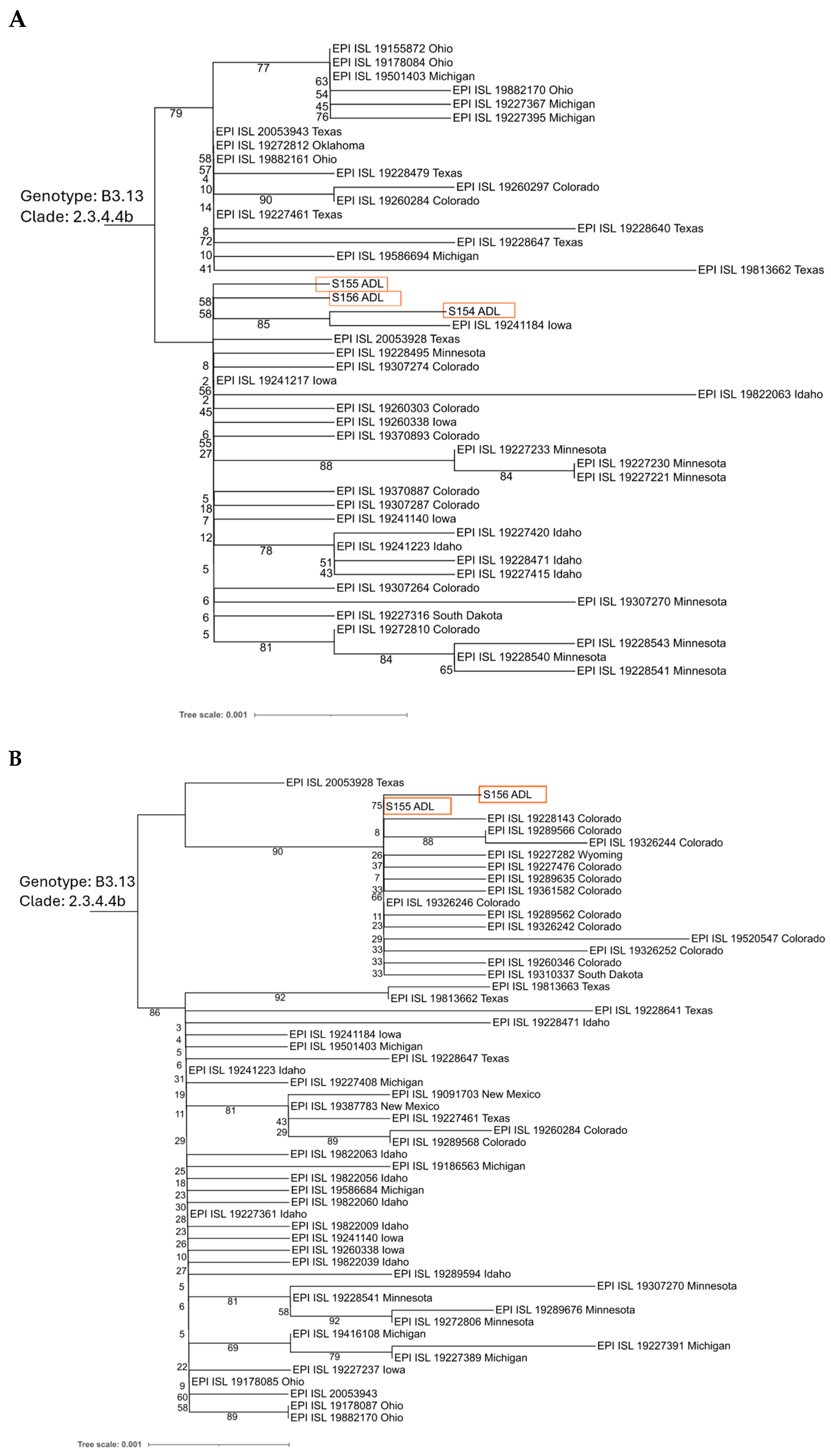

3.2.2. Phylogenetic and Lineage Analysis

3.2.3. Variant Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA | California |

| CO | Colorado |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| HA | Hemagglutinin |

| HPAIV | Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus |

| IAV | Influenza A virus |

| IN | Indiana |

| MD | Maryland |

| MI | Michigan |

| MN | Minnesota |

| MO | Missouri |

| NA | Neuraminidase |

| NJ | New Jersey |

| NMTS | National Milk Testing Strategy |

| NP | Nucleoprotein |

| NS | Non-structural protein |

| NS1 | Non-structural protein 1 |

| NY | New York |

| OH | Ohio |

| PA | Polymerase acidic |

| PB1 | Polymerase basic 1 |

| PB2 | Polymerase basic 2 |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| U.S. | United States |

| VA | Virginia |

References

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. Influenza: The Once and Future Pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125 (Suppl. S3), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elderfield, R.; Barclay, W. Influenza Pandemics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 719, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, W.N.; Kackos, C.M.; Webby, R.J. The Evolution and Future of Influenza Pandemic Preparedness. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreenivasan, C.C.; Li, F.; Wang, D. Emerging Threats of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in US Dairy Cattle: Understanding Cross-Species Transmission Dynamics in Mammalian Hosts. Viruses 2024, 16, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Grenfell, B.T. Heading off an Influenza Pandemic. Science 2005, 309, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F.; Hermann, E.; Rasmussen, A.L. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1: History, Current Situation, and Outlook. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0220924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yang, J.; Jiao, W.; Li, X.; Iqbal, M.; Liao, M.; Dai, M. Clade 2.3.4.4b Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses: Knowns, Unknowns, and Challenges. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e00424-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, L.C.; Frye, E.A.; Butt, S.L.; Laverack, M.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L.M.; Thompson, A.C.; Koscielny, M.P.; Cronk, B.; Johnson, A.; et al. Spillover of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus to Dairy Cattle. Nature 2024, 634, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-Q.; Hutter, C.R.; Markin, A.; Thomas, M.; Lantz, K.; Killian, M.L.; Janzen, G.M.; Vijendran, S.; Wagle, S.; Inderski, B.; et al. Emergence and Interstate Spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) in Dairy Cattle in the United States. Science 2025, 388, eadq0900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, E.R.; Magstadt, D.R.; Petersen, B.; Timmermans, S.J.; Gauger, P.C.; Zhang, J.; Siepker, C.; Mainenti, M.; Li, G.; Thompson, A.C.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webby, R.J.; Uyeki, T.M. An Update on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus, Clade 2.3.4.4b. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.L.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L.M.; Diel, D.G. Hot Topic: Influenza A H5N1 Virus Exhibits a Broad Host Range, Including Dairy Cows. JDS Commun. 2024, 5, S13–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodaran, L.; Jaeger, A.; Moncla, L.H. Intensive Transmission in Wild, Migratory Birds Drove Rapid Geographic Dissemination and Repeated Spillovers of H5N1 into Agriculture in North America. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture. APHIS Confirms D1.1 Genotype in Dairy Cattle in Nevada. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/program-update/aphis-confirms-d11-genotype-dairy-cattle-nevada-0 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Oguzie, J.U.; Marushchak, L.V.; Shittu, I.; Lednicky, J.A.; Miller, A.L.; Hao, H.; Nelson, M.I.; Gray, G.C. Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus among Dairy Cattle, Texas, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, M.R.; Fernández-Quintero, M.L.; Ji, W.; Rodriguez, A.J.; Han, J.; Ward, A.B.; Guthmiller, J.J. A Single Mutation in Dairy Cow-Associated H5N1 Viruses Increases Receptor Binding Breadth. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachler, E.; Gnirke, A.; McMahon, K.; Gomez, M.; Stenson, L.; Guevara-Reyes, C.; Knoll, H.; Hill, T.; Hill, S.; Messer, K.S.; et al. Establishing Methods to Monitor Influenza (A)H5N1 Virus in Dairy Cattle Milk, Massachusetts, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L.M.; de Oliveira, P.S.B.; Martin, N.H.; Koebel, K.J.; Ivanek, R.; Alcaine, S.D.; Diel, D.G. Thermal Inactivation Spectrum of Influenza A H5N1 Virus in Raw Milk. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwe, N.J.; Cool, K.; Breithaupt, A.; Schön, J.; Trujillo, J.D.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Kwon, T.; Ahrens, A.K.; Britzke, T.; McDowell, C.D.; et al. H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Dynamics in Experimentally Infected Calves and Cows. Nature 2025, 637, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, I.; Silva, D.; Oguzie, J.U.; Marushchak, L.V.; Olinger, G.G.; Lednicky, J.A.; Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Schneider, N.E.; Hao, H.; Gray, G.C. A One Health Investigation into H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus Epizootics on Two Dairy Farms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Lirola, L.G.; Cauwels, B.; Mora-Díaz, J.C.; Magtoto, R.; Hernández, J.; Cordero-Ortiz, M.; Nelli, R.K.; Gorden, P.J.; Magstadt, D.R.; Baum, D.H. Detection and Monitoring of Highly Pathogenic Influenza A Virus 2.3.4.4b Outbreak in Dairy Cattle in the United States. Viruses 2024, 16, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Milk Testing Strategy. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/livestock/nmts (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Spackman, E.; Anderson, N.; Walker, S.; Suarez, D.L.; Jones, D.R.; McCoig, A.; Colonius, T.; Roddy, T.; Chaplinski, N.J. Inactivation of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus with High-Temperature Short Time Continuous Flow Pasteurization and Virus Detection in Bulk Milk Tanks. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, H.L.; Wight, J.; Baz, M.; Dowding, B.; Flamand, L.; Hobman, T.; Jean, F.; Joy, J.B.; Lang, A.S.; MacParland, S.; et al. Longitudinal Screening of Retail Milk from Canadian Provinces Reveals No Detections of Influenza A Virus RNA (April-July 2024): Leveraging a Newly Established Pan-Canadian Network for Responding to Emerging Viruses. Can. J. Microbiol. 2025, 71, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spackman, E.; Jones, D.R.; McCoig, A.M.; Colonius, T.J.; Goraichuk, I.V.; Suarez, D.L. Characterization of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Retail Dairy Products in the US. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0088124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Wentworth, D.E. Influenza A Virus Molecular Virology Techniques. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 865, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Donnelly, M.E.; Scholes, D.T.; St George, K.; Hatta, M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Wentworth, D.E. Single-Reaction Genomic Amplification Accelerates Sequencing and Vaccine Production for Classical and Swine Origin Human Influenza a Viruses. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 10309–10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; Stech, J.; Guan, Y.; Webster, R.G.; Perez, D.R. Universal Primer Set for the Full-Length Amplification of All Influenza A Viruses. Arch. Virol. 2001, 146, 2275–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.S.; Uhm, S.; Killian, M.L.; Torchetti, M.K. An Evaluation of Avian Influenza Virus Whole-Genome Sequencing Approaches Using Nanopore Technology. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinet, K.; Srikanth, A.; Thielen, P.; England Biolabs, N.; Bonnevie, J. NEBNext iiMS Influenza A DNA Library Prep for Oxford Nanopore V1. 2024. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.n92ld8m9nv5b/v1 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Goraichuk, I.V.; Suarez, D.L. Custom Barcoded Primers for Influenza A Nanopore Sequencing: Enhanced Performance with Reduced Preparation Time. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1545032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegers, J.Y.; Wille, M.; Yann, S.; Tok, S.; Sin, S.; Chea, S.; Porco, A.; Sours, S.; Chim, V.; Chea, S.; et al. Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of Contemporary H14N2 Avian Influenza A Virus in Domestic Ducks in Southeast Asia (Cambodia). Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2297552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, J.D.; Merritt, B.; Gooden, H.; Siegers, J.Y.; Srikanth, A.; Yann, S.; Kol, S.; Sin, S.; Tok, S.; Karlsson, E.A.; et al. Improved Resolution of Avian Influenza Virus Using Oxford Nanopore R10 Sequencing Chemistry. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0188024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, E.; Lee, S.A. Avian Influenza Virus RNA Extraction. In Animal Influenza Viruses. Methods in Molecular Biology; Spackman, E., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2123, pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Spackman, E. Avian Influenza Virus Detection and Quantitation by Real-Time RT-PCR. In Animal Influenza Viruses. Methods in Molecular Biology; Spackman, E., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2123, pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Thielen, P. Influenza Whole Genome Sequencing with Integrated Indexing on Oxford Nanopore Platforms V1. 2022. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.kxygxm7yzl8j/v1 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Gangavarapu, K.; Quick, J.; Matteson, N.L.; De Jesus, J.G.; Main, B.J.; Tan, A.L.; Paul, L.M.; Brackney, D.E.; Grewal, S.; et al. An Amplicon-Based Sequencing Framework for Accurately Measuring Intrahost Virus Diversity Using PrimalSeq and IVar. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A Program for Annotating and Predicting the Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the Genome of Drosophila Melanogaster Strain W1118; Iso-2; Iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, D.L.; Goraichuk, I.V.; Killmaster, L.; Spackman, E.; Clausen, N.J.; Colonius, T.J.; Leonard, C.L.; Metz, M.L. Testing of Retail Cheese, Butter, Ice Cream, and Other Dairy Products for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in the US. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lail, A.J.; Vuyk, W.C.; Machkovech, H.; Minor, N.R.; Hassan, N.R.; Dalvie, R.; Emmen, I.E.; Wolf, S.; Kalweit, A.; Wilson, N.; et al. Amplicon Sequencing of Pasteurized Retail Dairy Enables Genomic Surveillance of H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus in United States Cattle. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, R.; Ashok, A.K.; Dey, A.A.; Kesavardhana, S. Decoding Non-Human Mammalian Adaptive Signatures of 2.3.4.4b H5N1 to Assess Its Human Adaptive Potential. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00948-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, B.; Choi, J.-M.; Bornholdt, Z.A.; Sankaran, B.; Rice, A.P.; Prasad, B.V.V. The Influenza A Virus Protein NS1 Displays Structural Polymorphism. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4113–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, R.; Yamada, S.; Le, M.Q.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Qurnianingsih, E.; Nidom, C.A.; Ito, M.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of PB2 Mutations Responsible for the Efficient Replication of H5N1 Influenza Viruses in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3947–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Jin, T.; Yu, X.; Liang, L.; Liu, G.; Jovic, D.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Z.; Pan, J.; Fan, G. Composition and Dynamics of H1N1 and H7N9 Influenza A Virus Quasispecies in a Co-Infected Patient Analyzed by Single Molecule Sequencing Technology. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 754445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youk, S.-S.; Lee, D.-H.; Leyson, C.M.; Smith, D.; Criado, M.F.; DeJesus, E.; Swayne, D.E.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.J. Loss of Fitness of Mexican H7N3 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Mallards after Circulating in Chickens. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00543-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Kawashita, N.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Elgendy, E.M.; Daidoji, T.; Ono, T.; Takagi, T.; Nakaya, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Watanabe, Y. PB2 Mutations Arising during H9N2 Influenza Evolution in the Middle East Confer Enhanced Replication and Growth in Mammals. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Trujillo, J.D.; McDowell, C.D.; Matias-Ferreyra, F.; Kafle, S.; Kwon, T.; Gaudreault, N.N.; Fitz, I.; Noll, L.; Morozov, I.; et al. Detection and Characterization of H5N1 HPAIV in Environmental Samples from a Dairy Farm. Virus Genes 2024, 60, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Biswas, A.; Guan, L.; Gu, C.; Maemura, T.; Trifkovic, S.; Wang, T.; Babujee, L.; Dahn, R.; Halfmann, P.J.; et al. Pathogenicity and Transmissibility of Bovine H5N1 Influenza Virus. Nature 2024, 633, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafers, J.; Warren, C.J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Cole, S.J.; Cooper, J.; Drewek, K.; Kolli, B.R.; McGinn, N.; Qureshi, M.; et al. Pasteurisation Temperatures Effectively Inactivate Influenza A Viruses in Milk. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Li, J.; Feng, L.; Chen, Q.; Meng, F.; Yang, H.; et al. Does Pasteurization Inactivate Bird Flu Virus in Milk? Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2364732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkie, T.N.; Nasheri, N.; Romero-Barrios, P.; Catford, A.; Krishnan, J.; Pama, L.; Hooper-McGrevy, K.; Nfon, C.; Cutts, T.; Berhane, Y. Effectiveness of Pasteurization for the Inactivation of H5N1 Influenza Virus in Raw Whole Milk. Food Microbiol. 2025, 125, 104653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, T.; Gebhardt, J.T.; Lyoo, E.L.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Gaudreault, N.N.; Morozov, I.; Diel, D.G.; Richt, J.A. Bovine Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus Stability and Inactivation in the Milk Byproduct Lactose. Viruses 2024, 16, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauring, A.S.; Martin, E.T.; Eisenberg, M.C.; Fitzsimmons, W.J.; Salzman, E.; Leis, A.M.; Lyon-Callo, S.; Bagdasarian, N. Surveillance of H5 HPAI in Michigan Using Retail Milk. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R.; Brown, I.H.; Crawshaw, T.R. Evidence of Influenza A Virus Infection in Dairy Cows with Sporadic Milk Drop Syndrome. Vet. Rec. 1999, 145, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.A.; Calvert, V.; McLaren, I.E. Retrospective Analysis of Serum and Nasal Mucus from Cattle in Northern Ireland for Evidence of Infection with Influenza A Virus. Vet. Rec. 2002, 150, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmailov, I.A.; Atamas’, V.A.; Kniazeva, N.I.; Petrova, M.S.; Kaimakan, P.V. Outbreak of Influenza among Cattle. Veterinariia 1973, 49, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K. An Outbreak of Cattle Influenza in Japan in the Fall of 1949. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1951, 118, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Romvary, J.; Takatsy, G.; Barb, K.; Farkas, E. Isolation of Influenza Virus Strains from Animals. Nature 1962, 193, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatkhuddinova, M.F.; Kir’ianova, A.I.; Isachenko, V.A.; Zakstel’skaia, L.I. Isolation and Identification of the A-Hong Kong (H3N2) Virus in Respiratory Diseases of Cattle. Vopr. Virusol. 1973, 18, 474–478. [Google Scholar]

- Tanyi, J.; Romváry, J.; Aldásy, P.; Mathé, Z. Isolation of Influenza a Virus Strains from Cattle. Prelim. Report. Acta Vet. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1974, 24, 341–343. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, I.H.; Crawshaw, T.R.; Harris, P.A.; Alexander, D.J. Detection of Antibodies to Influenza A Virus in Cattle in Association with Respiratory Disease and Reduced Milk Yield. Vet. Rec. 1998, 143, 637–638. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.H.; Easterday, B.C.; Webster, R.G. Strains of Hong Kong Influenza Virus in Calves. J. Infect. Dis. 1977, 135, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, T.R.; Brown, I.H.; Essen, S.C.; Young, S.C.L. Significant Rising Antibody Titres to Influenza A Are Associated with an Acute Reduction in Milk Yield in Cattle. Vet. J. 2008, 178, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, C.C.; Thomas, M.; Kaushik, R.S.; Wang, D.; Li, F. Influenza A in Bovine Species: A Narrative Literature Review. Viruses 2019, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant State | Plants Tested | Brands Tested | Samples Tested (% of Total) | IAV Positive Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 1 | 1 | 1 (0.47%) | 0 |

| CO | 1 | 2 | 28 (13.08%) | 20 |

| IN | 1 | 1 | 4 (1.87%) | 0 |

| MD | 1 | 1 | 1 (0.47%) | 0 |

| MI | 2 | 2 | 21 (9.81%) | 17 |

| MN | 2 | 1 | 6 (2.80%) | 0 |

| MO | 1 | 2 | 4 (1.87%) | 3 |

| NJ | 1 | 1 | 8 (3.74%) | 0 |

| NY | 6 | 7 | 41 (19.16%) | 3 |

| OH | 2 | 2 | 6 (2.80%) | 0 |

| PA | 21 | 16 | 88 (41.12%) | 0 |

| VA | 1 | 1 | 6 (2.80%) | 4 |

| Total | 40 | 38 | 214 (100.00%) | 47 |

| Brand | Plant | Product Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigerated | Shelf-Stable | |||||

| Skim | 1% | 2% | Whole | Whole | ||

| G | 2 | x | x | x | ||

| K | 3 | x | x | |||

| K | 5 | x | ||||

| AO | 8 | x | x | x | x | |

| A | 8 | x | x | x | ||

| A | 30 | x | x | |||

| AT | 30 | x | ||||

| Specimen | Genome Coverage | Full-Length Segments | Segment Sequence Coverage (Percentage) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (PB2) | 2 (PB1) | 3 (PA) | 4 (HA) | 5 (NP) | 6 (NA) | 7 (MP) | 8 (NS) | |||

| S154 | 87% | 7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| S155 | 60% | 5 | 20 | 41 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| S156 | 65% | 5 | 100 | 40 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Read Depth at Site (Variant Frequency) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoded Protein | Substitution | S154 | S155 | S156 |

| NS1 | R21Q | 326 (48.8%) | 321 (96.3%) | 324 (95.4%) |

| NS1 | E71G | 429 (24.5%) | n/a | n/a |

| NA | I443T | 830 (95.2%) | n/a | n/a |

| PB1 | S261G | 631 (99.5%) | * | * |

| PB1 | M321T | 676 (93.6%) | * | * |

| PB2 | E249G | n/a | * | 107 (97.2%) |

| PB2 | A255V | 619 (96.1%) | * | 107 (100.0%) |

| PB2 | V655A | 893 (89.5%) | * | n/a |

| PB2 | G673D | n/a | * | 112 (97.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gontu, A.; Sekhwal, M.K.; Diaz Huemme, A.; Li, L.; Kutsaya, S.; Ling, M.; Doshi, N.K.; Byukusenge, M.; Nissly, R.H. Pasteurized Milk Serves as a Passive Surveillance Tool for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Dairy Cattle. Viruses 2025, 17, 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101318

Gontu A, Sekhwal MK, Diaz Huemme A, Li L, Kutsaya S, Ling M, Doshi NK, Byukusenge M, Nissly RH. Pasteurized Milk Serves as a Passive Surveillance Tool for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Dairy Cattle. Viruses. 2025; 17(10):1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101318

Chicago/Turabian StyleGontu, Abhinay, Manoj K. Sekhwal, Anastacia Diaz Huemme, Lingling Li, Sophia Kutsaya, Michael Ling, Nidhi Kajal Doshi, Maurice Byukusenge, and Ruth H. Nissly. 2025. "Pasteurized Milk Serves as a Passive Surveillance Tool for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Dairy Cattle" Viruses 17, no. 10: 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101318

APA StyleGontu, A., Sekhwal, M. K., Diaz Huemme, A., Li, L., Kutsaya, S., Ling, M., Doshi, N. K., Byukusenge, M., & Nissly, R. H. (2025). Pasteurized Milk Serves as a Passive Surveillance Tool for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Dairy Cattle. Viruses, 17(10), 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101318