Prevalence of Hepatitis B in Canadian First-Time Blood Donors: Association with Social Determinants of Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Donor Data

2.2. Hepatitis B Testing

2.3. Chronic and Resolved Hepatitis B

2.4. Data Management and Statistics

Epidemiology Donor Database

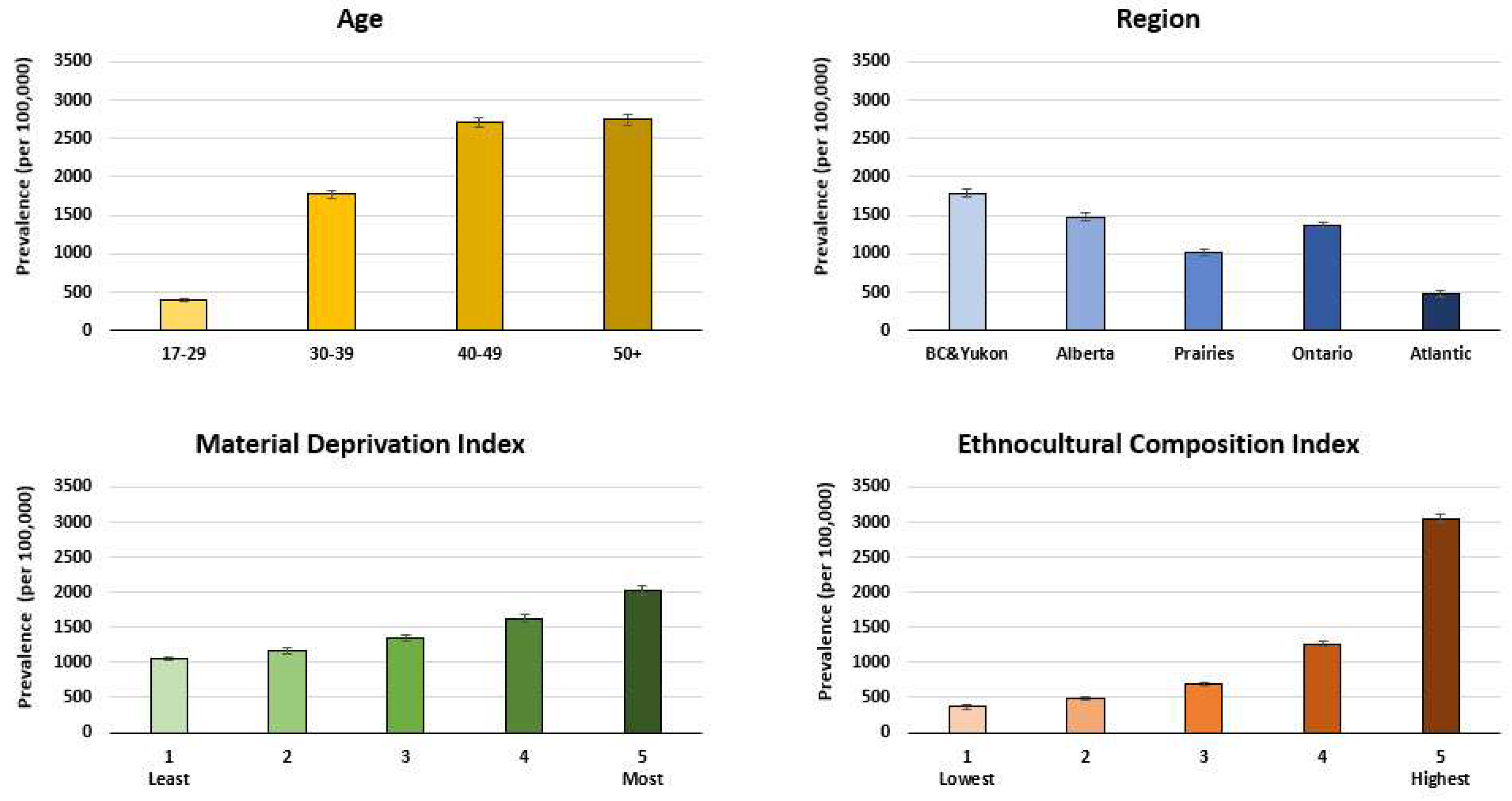

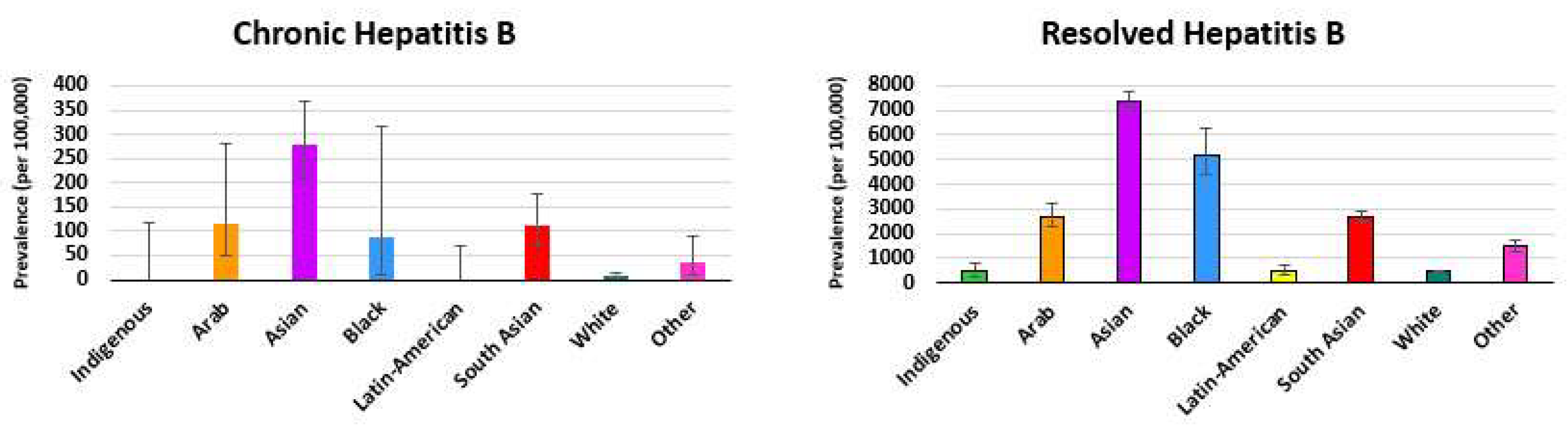

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lai, C.L.; Ratzui, V.; Yuen, M.F.; Poynard, T. Viral hepatitis B. Lancet 2003, 362, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin, C.S.; Fung, S.K.; Alvarez, F.; Cooper, C.L.; Doucette, K.E.; Fournier, C.; Kelly, E.; Ko, H.H.; Ma, M.M.; Martin, S.R.; et al. Management of hepatitis B infection: 2018 guidelines from the Canadian Association of the Study of the Liver and Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. Can. Liver J. 2018, 1, 156–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Update on the Recommended Use of Hepatitis B Vaccine. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/update-recommended-use-hepatitis-b-vaccine/update-recommended-use-hepatitis-b-vaccine-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Ghany, M.; Perrillo, R.; Belle, S.H.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Terrault, N.A.; Shuhart, M.C.; Lau, D.T.Y.; Kim, R.; Fried, M.W.; Sterling, R.K.; et al. Characteristics of adults in the Hepatitis B Research Network inNorth America reflect their country of origin and HBV genotype. Clin. Gastrolenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.M. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adults with emphasis on the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Viral Hepatitis, B. Guidance for National Strategic Planning (NSP): Health Sector Response to HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Lancet 2003, 362, 2089–2094. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373523/9789240076389-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- GBD 2019 Hepatitis B Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 796–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasseen, A.S.; Kwong, J.C.; Feld, J.J.; Kustra, R.; MacDonald, L.; Greenaway, C.C.; Janjua, N.Z.; Mazzulli, T.; Sherman, M.; Lapointe-Shaw, L.; et al. The viral hepatitis B care cascade: A population-based comparison of immigrant groups. Hepatology 2022, 75, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnyawali, B.; Pusateri, A.; Nickerson, A.; Jalil, S.; Mumtaz, K. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic factors impacting hepatitis B and related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 3793–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.H.P. Chronic hepatitis B in British Columbia. BMC Med. J. 2022, 64, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Coffin, C.S.; Fung, S.K.; Ma, M.M. Management of chronic hepatitis B: Canadian Association fo the Study of the Liver consensus guidelines. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.F.; Reedman, C.N.; Osiowy, C.; Bolotin, S.; Yi, Q.L.; Lourenco, L.; Lewin, A.; Binka, M.; Caffrey, N.; Drews, S.J. Hepatitis B blood donor screening data: An under-recognized resource for Canadian public health surveillance. Viruses 2023, 15, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Philibert, M.D.; Raymond, G.; Simpson, A. An area-based material and social deprivation index for public health in Quebec and Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 103, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Raymond, G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Health Promot. Chronis Dis. Prev. Can. 2009, 29, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation: Data Set and User Guide. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/45200001 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Matheson, F.I.; Dunn, J.R.; Smith, K.L.W.; Moineddin, R.; Glazier, R.H. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: A new tool for the study of inequity. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103, S12–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on Hepatitis B and C Surveillance in Canada: 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/report-hepatitis-b-c-canada-2019.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Roterman, M.; Langlois, K.; Andonov, A.; Trubnikov, M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections: Results from 2007 to 2009 and 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Study. Health Rep. 2013, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.K.; Nguyen, M.H.; Kim, W.R.; Gish, R.; Perumalswami, P.; Jaconson, I.M. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggild, A.K.; Geduld, J.; Libman, M.; Ward, B.J.; McCarthy, A.E.; Doyle, P.W.; Ghesquiere, W.; Voncelette, J.; Kuhn, S.; Freedman, D.O.; et al. Travel-acquired infections and illnesses in Canadians: Surveillance report from CanTravNet surveillance data, 2009–2011. Open Med. 2014, 8, e20–e32. [Google Scholar]

- Binka, M.; Buss, Z.A.; Wong, S.; Chong, M.; Buxton, J.; Chapinal, N.; Yu, A.; Alvarez, M.; Darvishian, M.; Wong, J.; et al. Differing profiles of people diagnosed with acute and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in British Columbia, Canada. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Canada at a Glance: Immigration. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x/2022001/sec2-eng.htm (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Wang, H.; Men, P.; Xiao, X.; Gao, P.; Lv, M.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, W.; Bai, S.; Wu, J. Hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, W.R.; Dodd, R.Y.; Notari, E.P.; Xu, M.; Nelson, D.; Kessler, D.A.; Reik, R.; Williams, A.E.; Custer, B.; Stramer, S.L. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus in United States blood donations: The Trasnfusion-Transmissible Infections Monitoring System (TTIMS). Transfusion 2020, 60, 2327–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappy, P.; Boizeau, L.; Candotti, D.; Le Cam, S.; Martinaud, C.; Pillonel, J.; Tribout, M.; Maugard, C.; Relave, J.; Richard, P.; et al. Insights on 21 years of HBV surveillance of blood donors in France. Viruses 2022, 14, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Kirby Institute. Transfusion-Transmissible Infections in Australia 2022 Surveillance Report. Available online: https://www.kirby.unsw.edu.au/research/reports/transfusion-transmissible-infections-australia-surveillance-report-2022 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Harvala, H.; Reynolds, C.; Gibney, Z.; Derrick, J.; Ijaz, S.; Davison, K.L.; Brailsford, S. Hepatitis B infections among blood donors in England between 2009 and 2018: Is occult hepatitis B infection a risk for blood safety? Transfusion 2021, 61, 2402–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayorinde, A.; Ghosh, I.; Ali, I.; Zahair, I.; Olarewaju, O.; Singh, M.; Meehan, E.; Anjorin, S.S.; Rotheram, S.; Barr, B.; et al. Health inequalities in infectious diseases: A systematic overview of reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteni, A.A.; Fortier, E.; Sylvestre, M.P.; Hoj, S.B.; Minoyan, N.; Gauvin, L.; Jutras-Aswad, D.; Bruneau, J. Socioeconomic stability is associated with lower injection frequency among people with distinct trajectories of injection drug use. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 94, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemstra, M.; Neudorf, C.; Opondo, J. Health disparity by neighbourhood income. Can. J. Public Health 2006, 97, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, G.; Coco, B.; Nardi, A.; Quartana, M.G.; Tosti, M.E.; Ferrigno, L.; Cacciola, I.; Messina, V.; Chessa, L.; Morisco, F.; et al. Trends in chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Italy over a 10-year period: Clues from the nationwide PITER and MASTER cohorts toward elimination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 129, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, M.; Swanevelder, R.; Van Zyl, G.; Lelie, N.; Murphy, E.L. An assessment of hepatitis B virus prevalence in South African young blood donors born after the implementation of the infant hepatitis B virus immunization program: Implications for transfusion safety. Transfusion 2021, 61, 2688–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Allain, J.P.; Wang, H.; Rong, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, K.; Xu, R.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Liao, Q.; et al. Incidence of hepatitis B virus infection in young Chinese blood donors born after mandatory implementation of neonatal hepatitis B vaccination nationwide. J. Viral Hepatol. 2018, 25, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, G.; Allain, J.P.; Brunetto, M.R.; Buendia, M.A.; Chen, D.S.; Colombo, M.; Craxi, A.; Donato, F.; Ferrari, C.; Gaeta, G.B.; et al. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2008, 49, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.F.; Yi, Q.L.; Fan, W.; Scalia, V.; Goldman, M.; Fearon, M.A. Residual risk of HIV, HCV and HBV in Canada. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2017, 56, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, W.R.; Dodd, R.Y.; Notari, E.P.; Haynes, J.; Anderson, S.A.; Williams, A.; Reik, R.; Kessler, D.; Custer, B.; Stramer, S.L. HIV, HCV, and HBV incidence and residual risk in US blood donors before and after implementation of the 12-month deferral policy for men who have sex with men. Transfusion 2021, 61, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajden, M.; McNabb, G.; Petric, M. The laboratory diagnosis of hepatitis B virus. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 16, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Case Definitions for Communicable Diseases under National Surveillance—2009. Available online: https:www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2009-35/definitions-communicable-diseases-national-surveillance.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Saita, C.; Pollicino, T.; Raimondo, G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: An update. Viruses 2022, 14, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.J.; Brosgart, C.L.; Welch, S.; Block, T.; Chen, M.; Cohen, C.; Kim, W.R.; Kowdley, K.V.; Lok, A.S.; Tsai, N.; et al. An updated assessment of chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign born persons living in the United States. Hepatology 2021, 74, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myran, D.T.; Morton, R.; Biggs, B.A.; Veldhuijzen, I.; Castelli, F.; Tran, A.; Staub, L.K.; Agbata, E.; Rahman, P.; Pareek, M.; et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for and vaccinating against hepatitis B virus among migrants in the EU.EEA: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, L.; Zanetti, A.R. Hepatitis B vaccination:A historical overview with a focus on the Italian achievements. Viruses 2022, 14, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Highlights from the 2021 Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey (cNICS). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-vaccines/vaccination-coverage/2021-highlights-childhood-national-immunization-coverage-survey.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Ontario Public Health. Immunization Coverage Report for School-Based Programs in Ontario: 2019-20, 2020–2021 and 2021-22 School Years with Impact of Catch-up Programs. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/I/2023/immunization-coverage-2019-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Biondi, M.J.; Marchand-Austin, A.; Cronin, K.; Nanwa, N.; Ravirajan, V.; Mandel, E.; Goneau, L.W.; Mazzulli, T.; Shah, H.; Capraru, C.; et al. Prenatal hepatitis B screening, and hepatitis B burden among children, in Ontario:A descriptive study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E1299–E1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, A.O.; Plitt, S.S.; Douglas, L.; Charlton, C.L. Overview of a provincial prenatal communicable disease screening program:2002–2016. J. Obs. Gynecol. Can. 2020, 43, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Feld, J.J.; Feng, Z.; Sander, B.; Wong, W.W.L. Feasibility of hepatitis B elimination in high-income countries with ongoing immigration. J. Viral Hepatol. 2022, 77, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chronic Hepatitis B (N = 850) | Resolved Hepatitis B (N = 20,667) | All Donors (N = 1,538,869) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 25.88 | 39.86 | 53.77 |

| Male | 74.12 | 60.14 | 46.23 |

| Age Group | |||

| 17-30 | 35.88 | 15.34 | 52.23 |

| 31-40 | 24.47 | 23.44 | 17.70 |

| 41-50 | 21.76 | 29.90 | 14.78 |

| >50 | 17.88 | 31.32 | 15.30 |

| Region | |||

| British Columbia | 20.82 | 20.80 | 15.58 |

| Alberta | 18.24 | 19.83 | 17.97 |

| Prairies | 9.18 | 7.96 | 10.53 |

| Ontario | 49.53 | 48.15 | 46.80 |

| Atlantic | 2.24 | 3.25 | 9.12 |

| Variable | Relative Risk (RR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (compared with female) | 2.98 | 2.53, 3.50 | <0.0001 |

| Age (compared with 17–30) | |||

| 31–40 | 1.83 | 1.52, 2.20 | <0.0001 |

| 41–50 | 2.16 | 1.78, 2.62 | <0.0001 |

| >50 | 2.04 | 1.66, 2.52 | <0.0001 |

| Region (compared with Ontario) | |||

| British Columbia | 1.15 | 0.96, 1.39 | 0.1323 |

| Alberta | 1.07 | 0.88, 1.31 | 0.4911 |

| Prairies | 1.19 | 0.93, 1.53 | 0.1669 |

| Atlantic | 0.62 | 0.38, 1.01 | 0.0557 |

| Year (compared with 2017–2022) | |||

| 2005–2008 | 1.66 | 1.37, 2.01 | <0.0001 |

| 2009–2012 | 1.30 | 1.07, 1.58 | 0.0081 |

| 2013–2016 | 0.98 | 0.80, 1.20 | 0.8399 |

| Material Deprivation Quintile (compared with quintile 1) | |||

| 2 | 1.22 | 0.96, 1.55 | 0.1103 |

| 3 | 1.18 | 0.92, 1.52 | 0.1945 |

| 4 | 1.61 | 1.26, 2.05 | 0.0001 |

| 5 | 2.11 | 1.65, 2.69 | <0.0001 |

| Ethnocultural Composition Quintile (compared with quintile 1) | |||

| 2 | 1.67 | 0.84, 3.33 | 0.1406 |

| 3 | 2.66 | 1.39, 5.08 | 0.0030 |

| 4 | 6.37 | 3.42, 11.88 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 12.35 | 6.68, 22.82 | <0.0001 |

| Variable | Relative Risk (RR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (compared with female) | 1.46 | 1.42, 1.51 | <0.0001 |

| Age (compared with 17–30) | |||

| 31–40 | 4.09 | 3.91, 4.28 | <0.0001 |

| 41–50 | 6.93 | 6.64, 7.23 | <0.0001 |

| > 50 | 8.22 | 7.88, 8.57 | <0.0001 |

| Region (compared with Ontario) | |||

| British Columbia | 1.07 | 1.03, 1.11 | 0.0002 |

| Alberta | 1.12 | 1.08, 1.16 | <0.0001 |

| Prairies | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.05 | 0.8002 |

| Atlantic | 0.73 | 0.68, 0.80 | <0.0001 |

| Year (compared with 2017–2022) | |||

| 2005–2008 | 0.85 | 0.82, 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| 2009–2012 | 0.88 | 0.84, 0.91 | <0.0001 |

| 2013–2016 | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.93 | <0.0001 |

| Material Deprivation Quintile (compared with quintile 1) | |||

| 2 | 1.09 | 1.04, 1.14 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 1.19 | 1.14, 1.25 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 1.33 | 1.27, 1.39 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 1.56 | 1.49, 1.64 | <0.0001 |

| Ethnocultural Composition Quintile (compared with quintile 1) | |||

| 2 | 1.28 | 1.16, 1.42 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 1.86 | 1.69, 2.05 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 3.50 | 3.19, 3.85 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 7.83 | 7.15, 8.58 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Brien, S.F.; Ehsani-Moghaddam, B.; Goldman, M.; Drews, S.J. Prevalence of Hepatitis B in Canadian First-Time Blood Donors: Association with Social Determinants of Health. Viruses 2024, 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16010117

O’Brien SF, Ehsani-Moghaddam B, Goldman M, Drews SJ. Prevalence of Hepatitis B in Canadian First-Time Blood Donors: Association with Social Determinants of Health. Viruses. 2024; 16(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Brien, Sheila F., Behrouz Ehsani-Moghaddam, Mindy Goldman, and Steven J. Drews. 2024. "Prevalence of Hepatitis B in Canadian First-Time Blood Donors: Association with Social Determinants of Health" Viruses 16, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16010117

APA StyleO’Brien, S. F., Ehsani-Moghaddam, B., Goldman, M., & Drews, S. J. (2024). Prevalence of Hepatitis B in Canadian First-Time Blood Donors: Association with Social Determinants of Health. Viruses, 16(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16010117