Understanding the Central Nervous System Symptoms of Rotavirus: A Qualitative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Histopathological Mechanisms of Rotavirus Infection

3. Brain–Gut Communication in Rotavirus Infection

4. Role of the ENS in Rotavirus Infection

5. CNS Complications in Rotavirus Infection

6. Pathophysiology of CNS Complications

7. Conclusions

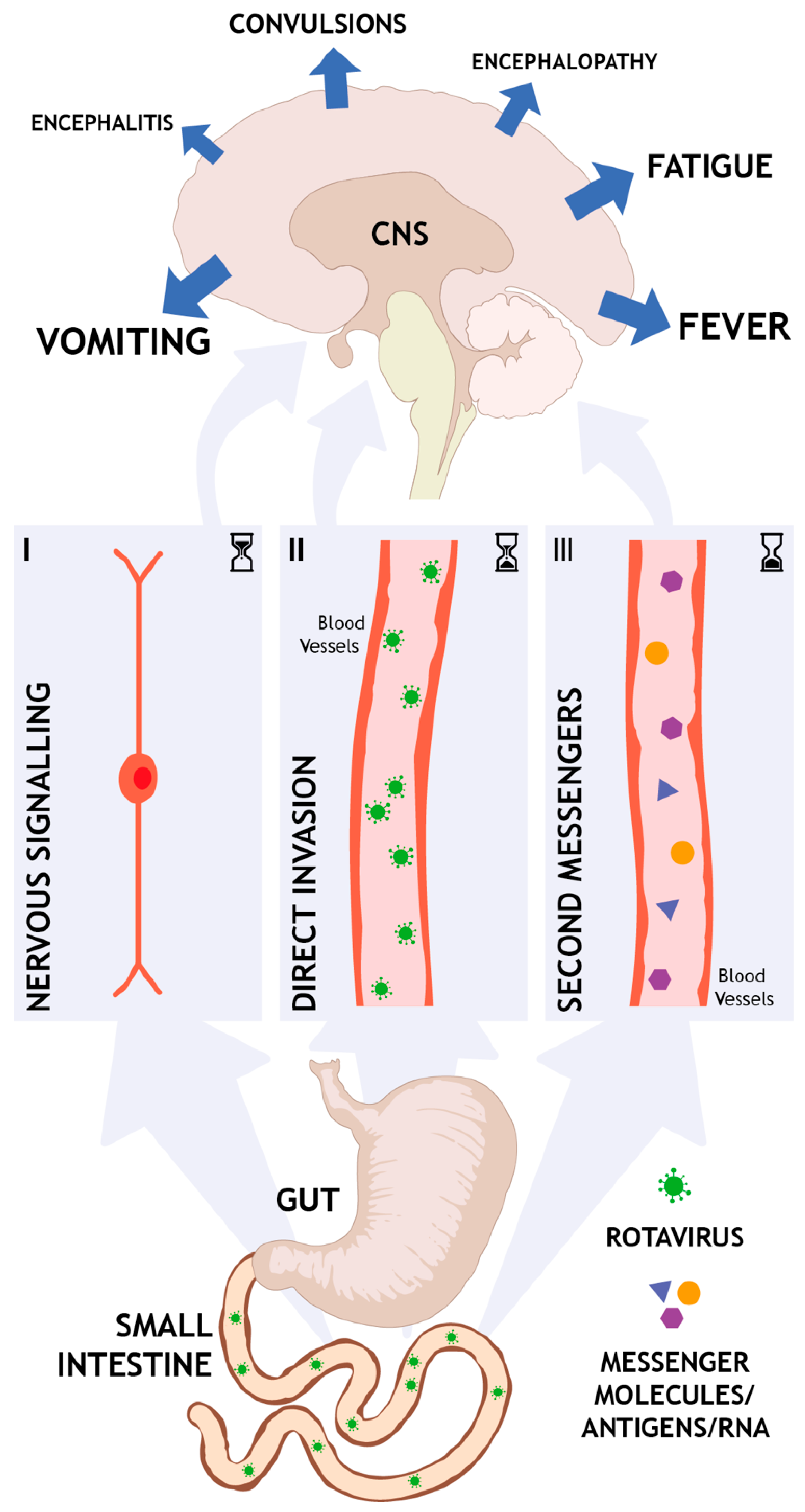

- Nervous route. At the site of infection in the intestines, released mediators such as NSP4 and/or serotonin can activate the ENS and vagal afferents that, through nervous communication, signal to the brain. This nervous pathway is direct, fast, can occur early in the course of the disease, and is not interrupted by defense mechanisms like the BBB.

- Direct invasion. In a host that suffers from malnutrition or immunodeficiency and exhibit e.g., dysfunction in the BBB, virus can potentially enter the brain. The virus can also enter the lymphatic system, from where it is spread to other organs, including the CNS. This route obviously requires a weakened host and can only occur later in the course of the disease when the virus has already replicated several rounds and virions are present in high titers. However, the causality of direct invasion remains obscure since rotavirus cannot always be found in CSF.

- Second messengers. Systemic elevation of toxins, cytokines, and/or other messengers can indirectly induce CNS effects. This kind of CNS response is per definition occurring later in the course of the disease and is likely part of a coordinated immune response.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tate, J.E.; Burton, A.H.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Parashar, U.D.; World Health Organization–Coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000–2013. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, S96–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troeger, C.; Khalil, I.A.; Rao, P.C.; Cao, S.; Blacker, B.F.; Ahmed, T.; Armah, G.; Bines, J.E.; Brewer, T.G.; Colombara, D.V. Rotavirus Vaccination and the Global Burden of Rotavirus Diarrhea Among Children Younger Than 5 Years. JAMA Pediatr 2018, 172, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, K.N.; Travagli, R.A. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1339–1368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horn, C.C. Why is the neurobiology of nausea and vomiting so important? Appetite 2008, 50, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, L.M.; Kent, S.; Pittman, Q.J.; Roth, J. Fever and sickness behavior: Friend or foe? Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 50, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Lee, B.; Azimi, P.; Gentsch, J.; Glaser, C.; Gilliam, S.; Chang, H.G.; Ward, R.; Glass, R.I. Rotavirus and central nervous system symptoms: Cause or contaminant? Case reports and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoyama, M.; Ichiyama, T.; Matsushige, T.; Kajimoto, M.; Shiraishi, M.; Furukawa, S. Clinical characteristics of benign convulsions with rotavirus gastroenteritis. J. Child. Neurol. 2009, 24, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFazio, M.P.; Braun, L.; Freedman, S.; Hickey, P. Rotavirus-induced seizures in childhood. J. Child. Neurol. 2007, 22, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, H.B.; Estes, M.K. Rotaviruses: From pathogenesis to vaccination. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagbom, M.; Istrate, C.; Engblom, D.; Karlsson, T.; Rodriguez-Diaz, J.; Buesa, J.; Taylor, J.A.; Loitto, V.M.; Magnusson, K.E.; Ahlman, H. Rotavirus stimulates release of serotonin (5-HT) from human enterochromaffin cells and activates brain structures involved in nausea and vomiting. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Blutt, S.E.; Ettayebi, K.; Zeng, X.L.; Broughman, J.R.; Crawford, S.E.; Karandikar, U.C.; Sastri, N.P.; Conner, M.E.; Opekun, A.R. Human Intestinal Enteroids: A New Model To Study Human Rotavirus Infection, Host Restriction, and Pathophysiology. J. Virol. 2015, 90, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellono, N.W.; Bayrer, J.R.; Leitch, D.B.; Castro, J.; Zhang, C.; O’Donnell, T.A.; Brierley, S.M.; Ingraham, H.A.; Julius, D. Enterochromaffin Cells Are Gut Chemosensors that Couple to Sensory Neural Pathways. Cell 2017, 170, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.F.; Davidson, G.P.; Holmes, I.H.; Ruck, B.J. Virus particles in epithelial cells of duodenal mucosa from children with acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis. Lancet 1973, 2, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.P.; Barnes, G.L. Structural and functional abnormalities of the small intestine in infants and young children with rotavirus enteritis. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1979, 68, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipe, D.M.; Howley, P.M. Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, M.K.; Kang, G.; Zeng, C.Q.; Crawford, S.E.; Ciarlet, M. Pathogenesis of rotavirus gastroenteritis. Novartis Found. Symp. 2001, 238, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bialowas, S.; Hagbom, M.; Nordgren, J.; Karlsson, T.; Sharma, S.; Magnusson, K.E.; Svensson, L. Rotavirus and Serotonin Cross-Talk in Diarrhoea. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, R. Serotonin and GI clinical disorders. Neuropharmacology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Minami, M.; Hirafuji, M.; Ogawa, T.; Akita, K.; Nemoto, M.; Saito, H.; Yoshioka, M.; Parvez, S.H. Neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of emesis—The role of serotonin. Toxicology 2000, 153, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.B.; Witte, A.B. The role of serotonin in intestinal luminal sensing and secretion. Acta Physiol. 2008, 193, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordasti, S.; Sjovall, H.; Lundgren, O.; Svensson, L. Serotonin and vasoactive intestinal peptide antagonists attenuate rotavirus diarrhoea. Gut 2004, 53, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikander, A.; Rana, S.V.; Prasad, K.K. Role of serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2009, 403, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, D.M.; Grider, J.R. Serotonin and colonic motility. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 27, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedio, M.M.; Hyman, N.; Mawe, G.M. Serotonin and its role in colonic function and in gastrointestinal disorders. Dis. Colon Rectum 2007, 50, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, B.E.; Bindslev, N.; Poulsen, S.S.; Larsen, R.; Hansen, M.B. Functional characterization of serotonin receptor subtypes in human duodenal secretion. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 98, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremon, C.; Carini, G.; Wang, B.; Vasina, V.; Cogliandro, R.F.; De Giorgio, R.; Stanghellini, V.; Grundy, D.; Tonini, M.; De Ponti, F.; et al. Intestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron activation, and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, C. Serotonin in pain and analgesia: Actions in the periphery. Mol. Neurobiol. 2004, 30, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Schultea, T. Serotonin 5-HT(3) receptor mediation of pain and anti-nociception: Implications for clinical therapeutics. Pain Physician 2004, 7, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Denna, T.H.; Storkersen, J.N.; Gerriets, V.A. Beyond a neurotransmitter: The role of serotonin in inflammation and immunity. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 140, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloez-Tayarani, I.; Changeux, J.P. Nicotine and serotonin in immune regulation and inflammatory processes: A perspective. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M.D.; Tack, J. The serotonin signaling system: From basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, O.; Peregrin, A.T.; Persson, K.; Kordasti, S.; Uhnoo, I.; Svensson, L. Role of the enteric nervous system in the fluid and electrolyte secretion of rotavirus diarrhea. Science 2000, 287, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powley, T.L.; Spaulding, R.A.; Haglof, S.A. Vagal afferent innervation of the proximal gastrointestinal tract mucosa: Chemoreceptor and mechanoreceptor architecture. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011, 519, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, M.B.; Deak, T.; Schiml, P.A. Sociality and sickness: Have cytokines evolved to serve social functions beyond times of pathogen exposure? Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 37, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmi, T.T.; Arstila, P.; Koivikko, A. Central nervous system involvement in patients with rotavirus gastroenteritis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1978, 10, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contino, M.F.; Lebby, T.; Arcinue, E.L. Rotaviral gastrointestinal infection causing afebrile seizures in infancy and childhood. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1994, 12, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.L.; Joensuu, J.; Vesikari, T. Detection of rotavirus RNA in cerebrospinal fluid in a case of rotavirus gastroenteritis with febrile seizures. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1996, 15, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.W.; Moon, C.H.; Lee, K.Y. Association of Rotavirus with Seizures Accompanied by Cerebral White Matter Injury in Neonates. J. Child. Neurol. 2015, 30, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.J.; Price, Z.; Bruckner, D.A. Aseptic meningitis in an infant with rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 1984, 3, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushijima, H.; Bosu, K.; Abe, T.; Shinozaki, T. Suspected rotavirus encephalitis. Arch. Dis. Child. 1986, 61, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, A.; Kawamitu, T.; Tanaka, R.; Okumura, M.; Yamakura, S.; Takasaki, Y.; Hiramatsu, H.; Momoi, T.; Iizuka, M.; Nakagomi, O. Rotavirus encephalitis: Detection of the virus genomic RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a child. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1995, 14, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rotbart, H.A. Rotavirus-associated hemorrhagic shock and encephalopathy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smeets, C.C.; Brussel, W.; Leyten, Q.H.; Brus, F. First report of Guillain-Barre syndrome after rotavirus-induced gastroenteritis in a very young infant. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2000, 159, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekgul, H.; Kutukculer, N.; Caglayan, S.; Tutuncuoglu, S. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, lymphocyte subsets and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Turk. J. Pediatr. 1998, 40, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamihiro, N.; Higashigawa, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Yoshino, A.; Sakata, K.; Nashida, Y.; Maji, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Inoue, M. Acute motor-sensory axonal Guillain-Barre syndrome with unilateral facial nerve paralysis after rotavirus gastroenteritis in a 2-year-old boy. J. Infect. Chemother. 2012, 18, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, J.; Miyamoto, T.; Ando, N.; Kubota, T.; Oka, M.; Kato, Z.; Hamano, S.; Hirabayashi, S.; Kikuchi, M.; Barkovich, A.J. Clinical and radiological features of rotavirus cerebellitis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010, 31, 1591–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiihara, T.; Watanabe, M.; Honma, A.; Kato, M.; Morita, Y.; Ichiyama, T.; Maruyama, K. Rotavirus associated acute encephalitis/encephalopathy and concurrent cerebellitis: Report of two cases. Brain Dev. 2007, 29, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paketci, C.; Edem, P.; Okur, D.; Sarioglu, F.C.; Guleryuz, H.; Bayram, E.; Kurul, S.H.; Yis, U. Rotavirus encephalopathy with concomitant acute cerebellitis: Report of a case and review of the literature. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2020, 62, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Gowdie, P.J.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Doherty, R.R.; Fahey, M. Rotavirus cerebellitis: New aspects to an old foe? Pediatr. Neurol. 2012, 46, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigrovic, L.E.; Lumeng, C.; Landrigan, C.; Chiang, V.W. Rotavirus cerebellitis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kato, Z.; Sasai, H.; Funato, M.; Asano, T.; Kondo, N. Acute cerebellitis associated with rotavirus infection. World J. Pediatr. 2013, 9, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosetti, F.M.; Castagno, E.; Raino, E.; Migliore, G.; Pagliero, R.; Urbino, A.F. Acute rotavirus-associated encephalopathy and cerebellitis. Minerva Pediatr. 2016, 68, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keidan, I.; Shif, I.; Keren, G.; Passwell, J.H. Rotavirus encephalopathy: Evidence of central nervous system involvement during rotavirus infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1992, 11, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. Rotavirus antigenemia in children with encephalopathy accompanied by rotavirus gastroenteritis. Arch. Virol. 2005, 150, 1927–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, R.F.; Forster, J. The CNS symptoms of rotavirus infections under the age of two. Clin. Padiatr. 1999, 211, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Araki, K.; Kodama, H.; Fujita, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Ushijima, H. Infantile convulsions with mild gastroenteritis. Brain Dev. 2000, 22, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V. Acute gastroenteritis-related encephalopathy. J. Child. Neurol. 2001, 16, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Bozdayi, G.; Mitui, M.T.; Ahmed, S.; Kabir, L.; Buket, D.; Bostanci, I.; Nishizono, A. Circulating rotaviral RNA in children with rotavirus antigenemia. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2013, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, I.; Taniguchi, K.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Maeno, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Yui, A.; Komoto, S.; Wakata, Y.; Matsubara, T.; Ozaki, N. Sudden death from systemic rotavirus infection and detection of nonstructural rotavirus proteins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4382–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blutt, S.E.; Matson, D.O.; Crawford, S.E.; Staat, M.A.; Azimi, P.; Bennett, B.L.; Piedra, P.A.; Conner, M.E. Rotavirus antigenemia in children is associated with viremia. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilger, M.A.; Matson, D.O.; Conner, M.E.; Rosenblatt, H.M.; Finegold, M.J.; Estes, M.K. Extraintestinal rotavirus infections in children with immunodeficiency. J. Pediatr. 1992, 120, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, Z.Y. Viremia and extraintestinal infections in infants with rotavirus diarrhea. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao 2003, 23, 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, S.; Ushijima, H.; Nishimura, S.; Shiraishi, H.; Kanazawa, C.; Abe, T.; Kaneko, K.; Fukuyama, Y. Detection of rotavirus in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of patients with convulsions and gastroenteritis by means of the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Brain Dev. 1993, 15, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, M.; Tanabe, Y.; Shinozaki, K.; Matsuno, S.; Furuya, T. Haemorrhagic shock and encephalopathy associated with rotavirus infection. Acta Paediatr. 1996, 85, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongou, K.; Konishi, T.; Yagi, S.; Araki, K.; Miyawaki, T. Rotavirus encephalitis mimicking afebrile benign convulsions in infants. Pediatr. Neurol. 1998, 18, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, C.; Steele, D.; Gwamanda, P.; Driessen, M. A neonatal death associated with rotavirus infection--detection of rotavirus dsRNA in the cerebrospinal fluid. S. Afr. Med. J. 2000, 90, 364–365. [Google Scholar]

- Medici, M.C.; Abelli, L.A.; Guerra, P.; Dodi, I.; Dettori, G.; Chezzi, C. Case report: Detection of rotavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a child with rotavirus gastroenteritis and meningism. J. Med. Virol. 2011, 83, 1637–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, J.S.; Park, C.H. White matter injury following rotavirus infection in neonates: New aspects to a forgotten entity, ‘fifth day fits’? Korean J. Pediatr. 2016, 59, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, J. Febrile encephalopathy and diarrhoea in infancy: Do not forget this culprit. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e231195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J.; Kinney, H.C.; Jensen, F.E.; Rosenberg, P.A. The developing oligodendrocyte: Key cellular target in brain injury in the premature infant. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Seo, J.H.; Park, J.S.; Park, E.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Woo, H.O.; Youn, H.S.; Choi, D.S.; Chung, J.Y.; et al. Distinctive pattern of white matter injury in neonates with rotavirus infection. Neurology 2015, 84, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Oh, K.W.; Weon, Y.C.; Choi, S.H. Neonatal seizures accompanied by diffuse cerebral white matter lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging are associated with rotavirus infection. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2014, 18, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, J.S.; Seo, J.H.; Park, E.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Park, C.H.; Woo, H.O.; Youn, H.S. Role of Ca2+ homeostasis disruption in rotavirus-associated seizures. J. Child. Neurol. 2014, 29, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weclewicz, K.; Kristensson, K.; Greenberg, H.B.; Svensson, L. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated VP7 of rotavirus is targeted to axons and dendrites in polarized neurons. J. Neurocytol. 1993, 22, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Oguchi, S.; Sato, M. Prostaglandins in the plasma and stool of children with rotavirus gastroenteritis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1989, 9, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Moon, C.H.; Choi, S.H. Type I interferon and proinflammatory cytokine levels in cerebrospinal fluid of newborns with rotavirus-associated leukoencephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2018, 40, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morichi, S.; Urabe, T.; Morishita, N.; Takeshita, M.; Ishida, Y.; Oana, S.; Yamanaka, G.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Kawashima, H. Pathological analysis of children with childhood central nervous system infection based on changes in chemokines and interleukin-17 family cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, H.; Inage, Y.; Ogihara, M.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Takekuma, K.; Hoshika, A.; Mori, T.; Watanabe, Y. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid nitrite/nitrate levels in patients with rotavirus gastroenteritis induced convulsion. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, Y.; Kawashima, H.; Suzuki, S.; Nishimata, S.; Takekuma, K.; Hoshika, A. Marked Elevation of Excitatory Amino Acids in Cerebrospinal Fluid Obtained From Patients With Rotavirus-Associated Encephalopathy. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2015, 29, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Offit, P.A. Rotavirus-specific proteins are detected in murine macrophages in both intestinal and extraintestinal lymphoid tissues. Microb. Pathog. 1998, 24, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Profaci, C.P.; Munji, R.N.; Pulido, R.S.; Daneman, R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease: Important unanswered questions. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, C.A.; Acosta, O. Inflammatory and oxidative stress in rotavirus infection. World J. Virol. 2016, 5, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Snipes-Magaldi, L.; Dennehy, P.; Keyserling, H.; Holman, R.C.; Bresee, J.; Gentsch, J.; Glass, R.I. Cytokines as mediators for or effectors against rotavirus disease in children. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2003, 10, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushijima, H.; Xin, K.Q.; Nishimura, S.; Morikawa, S.; Abe, T. Detection and sequencing of rotavirus VP7 gene from human materials (stools, sera, cerebrospinal fluids, and throat swabs) by reverse transcription and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994, 32, 2893–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1988, 12, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurgur, H.; Pinteaux, E. Microglia in the Neurovascular Unit: Blood-Brain Barrier-microglia Interactions After Central Nervous System Disorders. Neuroscience 2019, 405, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Kwon, Y.S. Benign convulsion with mild gastroenteritis. Korean J. Pediatr. 2014, 57, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Pomales, Y.T.; Krzyzaniak, M.; Coimbra, R.; Baird, A.; Eliceiri, B.P. Vagus nerve stimulation blocks vascular permeability following burn in both local and distal sites. Burns 2013, 39, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zanden, E.P.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; de Jonge, W.J. The vagus nerve as a modulator of intestinal inflammation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009, 21, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Westerloo, D.J.; Giebelen, I.A.; Florquin, S.; Bruno, M.J.; Larosa, G.J.; Ulloa, L.; Tracey, K.J.; van der Poll, T. The vagus nerve and nicotinic receptors modulate experimental pancreatitis severity in mice. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovikova, L.V.; Ivanova, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Botchkina, G.I.; Watkins, L.R.; Wang, H.; Abumrad, N.; Eaton, J.W.; Tracey, K.J. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 2000, 405, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca, A.S.; Gallina, A.L.; Tarnawski, L.; Tracey, K.J.; Pavlov, V.A.; Levine, Y.A.; Olofsson, P.S. An Effective Method for Acute Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Experimental Inflammation. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheadle, G.A.; Costantini, T.W.; Bansal, V.; Eliceiri, B.P.; Coimbra, R. Cholinergic signaling in the gut: A novel mechanism of barrier protection through activation of enteric glia cells. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 2014, 15, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheadle, G.A.; Costantini, T.W.; Lopez, N.; Bansal, V.; Eliceiri, B.P.; Coimbra, R. Enteric glia cells attenuate cytomix-induced intestinal epithelial barrier breakdown. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langness, S.; Kojima, M.; Coimbra, R.; Eliceiri, B.P.; Costantini, T.W. Enteric glia cells are critical to limiting the intestinal inflammatory response after injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 312, G274–G282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruwaka, K.; Ikegami, A.; Tachibana, Y.; Ohno, N.; Konishi, H.; Hashimoto, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Kato, D.; Ono, R.; Kiyama, H. Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hellysaz, A.; Hagbom, M. Understanding the Central Nervous System Symptoms of Rotavirus: A Qualitative Review. Viruses 2021, 13, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040658

Hellysaz A, Hagbom M. Understanding the Central Nervous System Symptoms of Rotavirus: A Qualitative Review. Viruses. 2021; 13(4):658. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040658

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellysaz, Arash, and Marie Hagbom. 2021. "Understanding the Central Nervous System Symptoms of Rotavirus: A Qualitative Review" Viruses 13, no. 4: 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040658

APA StyleHellysaz, A., & Hagbom, M. (2021). Understanding the Central Nervous System Symptoms of Rotavirus: A Qualitative Review. Viruses, 13(4), 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040658