Abstract

Two distinct phenomena of airborne transmission of variola virus (smallpox) were described in the pre-eradication era—direct respiratory transmission, and a unique phenomenon of transmission over greater distances, referred to as “aerial convection”. We conducted an analysis of data obtained from a systematic review following the PRISMA criteria, on the long-distance transmission of smallpox. Of 8179 studies screened, 22 studies of 17 outbreaks were identified—12 had conclusive evidence of aerial convection and five had partially conclusive evidence. Aerial convection was first documented in 1881 in England, when smallpox incidence had waned substantially following mass vaccination, making unusual transmissions noticeable. National policy at the time stipulated spatial separation of smallpox hospitals from other buildings and communities. The evidence supports the transmission of smallpox through aerial convection at distances ranging from 0.5 to 1 mile, and one instance of 15 km related to bioweapons testing. Other explanations are also possible, such as missed chains of transmission, fomites or secondary aerosolization from contaminated material such as bedding. The window of observation of aerial convection was within the 100 years prior to eradication. Aerial convection appears unique to the variola virus and is not considered in current hospital infection control protocols. Understanding potential aerial convection of variola should be an important consideration in planning for smallpox treatment facilities and protecting potential contacts and surrounding communities.

1. Introduction

Smallpox was a widespread disease in humans caused by the variola virus, which is a member of the poxvirus family [1]. Smallpox was declared eradicated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1980, following successful vaccination campaigns and other favorable conditions [2]. However, smallpox poses a public health threat of re-emergence due to the absence of mass vaccination, waning immunity and advances in synthetic biology, which make synthesis of variola possible [3,4]. Smallpox transmission occurs from person to person, primarily through respiratory droplets but can also transmitted through contact with infected clothing and bedding [5]. The R0 is estimated to be around 5 [6]. Whilst most pathogens have a dominant mode of transmission, they usually have more than one mode of transmission, and quantifying the relative contributions of different modes of transmission in the spread of an infection is difficult [7]. Two distinct phenomena of airborne transmission are described with variola—firstly, direct person-to-person transmission by the airborne respiratory route, and secondly, transmission over greater distances, sometimes over a mile, referred to as “aerial convection” [8].

It is believed that variola virus can transmit through the airborne, aerosol and contact routes, and some cases of indirect spread via fine particle aerosols or fomites have been reported [9,10,11,12]. The risk of person-to-person airborne infection is a function of the virus concentration in respiratory fluid, the expiratory event rate, the size and volume distribution of the particles emitted per expiratory event, the receptor’s breathing rate, exposure duration, and the receptor’s location in the room relative to the source case [12]. There have been various experimental studies on animals, which confirm that infection can be produced by a single plaque-forming unit (PFU) of virus carried in respirable particles—even a submicrometric aerosol of variola can cause infection in animals [12,13,14,15].

Smallpox can be transmitted through aerosols and the airborne route, as evidenced by air-sampling techniques together with culture and molecular detection methods [16]. There is also evidence showing the association between ventilation and the control of airflow directions in buildings and the transmission of infectious diseases [17]. Airborne transmission accounts for at least 10% of all nosocomial infections, based on patient-based surveillance systems and environmental sampling techniques in hospital settings [16,18].

Smallpox can survive in the environment under certain conditions and contaminated particles may be still isolated from the air in the later stages of the disease corresponding to a smaller number of lesions [19]. Thomas (1974) recovered the smallpox virus from an isolation unit using an adhesive surface air-sampling technique in the presence of very low aerosol concentrations [20]. A review of the literature suggests that the role of airborne transmission may have been underestimated in many instances [21].

In addition to direct respiratory transmission from person to person within 1–2 m of spatial separation, a more distant transmission has been described. Whilst it is well-established that airborne infection can occur [8,19], the spread of smallpox by means of “aerial convection” is less well understood. Aerial convection refers to transmission over a substantial distance, (greater than expected during direct person to person respiratory transmission of 1–2 metres and possibly aided by wind or air currents) a concept accepted by many epidemiologists. In recognition of this, the Ministry of Health regulations in Britain in the 1940s stipulated that smallpox hospitals should be “at least a quarter of a mile from another institution or a population of 200, and at least a mile from a population of 600” [8].

Aerosol transmission can occur over short distances or long distances, and the transmission is primarily governed by air flows driven by pressure differences generated by ventilation systems, open windows and doors, movement of people or temperature differences [16]. Aerosolised particles have the potential to remain suspended in the air for hours and can expose a larger number of susceptible individuals to potential infections at a greater distance from the source [21]. Our understanding of respiratory transmission and measurement methods have improved substantially since eradication [22], which makes it timely to review the evidence. Now 40 years since clinicians and public health agencies have managed smallpox, there is a need to review the pre-eradication human evidence around smallpox transmission, especially the role of aerial convection, for which there is little awareness among contemporary clinicians. This is essential to inform disease control strategies and health care worker occupational safety in preparedness planning.

The aim of this paper was to study the data and epidemiology of transmission of variola by aerial convection, and examine the hypothesis that aerial convection was only observed when the incidence of smallpox is sufficiently low to exclude other sources of infection.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the phenomenon of aerial convection was observed in the last 100 years of smallpox endemicity in the world, we examined the incidence of smallpox using the best available data, in relation to the period of observation of aerial convection. We used the systematic review methodology to identify data and evidence for aerial convection, and then analysed incidence data, documented distances of transmission, and the period of observation of aerial convection in relation to the epidemiology of smallpox deaths.

2.1. Smallpox Data Analysis

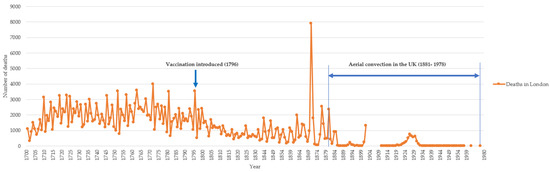

In order to clearly demonstrate the window during which aerial convection was observed relative to the epidemiology of the disease, we created the timeline of all identified observations of aerial convection that was plotted over the number of smallpox deaths using available data in London from 1700–1980. London was selected because there was better data for deaths (than cases) than global data or other countries, and the largest number of observations of aerial convection were from England.

We collected the data of the annual number of deaths from smallpox in London from 1700 to 1902 [23]. Due to missing data on deaths in London between 1903 and 1958, we collected the available data to estimate data for London, including (1) the number of deaths from smallpox in England and Wales from 1911 to 1919 [24], (2) population in London, England and Wales in 1911 (26), (3) number of cases and case fatality rate in the UK from 1920–1958 [25], and (4) the number of deaths in London between 1959 and 1980 [26,27,28].

We estimated that the annual deaths in London were 13% of deaths in England and Wales between 1911 and 1919, according to the population in London (4.52 million) taking 13% of the population in England and Wales (36.07 million) in 1911 [29]. Using the case fatality rate of 30% [30], we calculated the annual number of deaths in the UK from 1920 to 1958 based on the yearly reported cases [31]. The annual deaths in London were 17% of deaths in the UK between 1920 and 1958, according to the population in London (7.39 million) [32] taking 17% of the UK population (43.90 million) in 1921 [33]. The deaths in London between 1958 and 1980 were extracted from documented smallpox outbreaks in the UK [26,27,28]. These different data sources were used to create a timeline of smallpox deaths in London from 1700–1980. Then we plotted all identified observations of aerial convection over this timeline, to show the relationship of this observation period of aerial convection to the epidemiology of smallpox and the waning incidence of smallpox.

2.2. Search Strategy

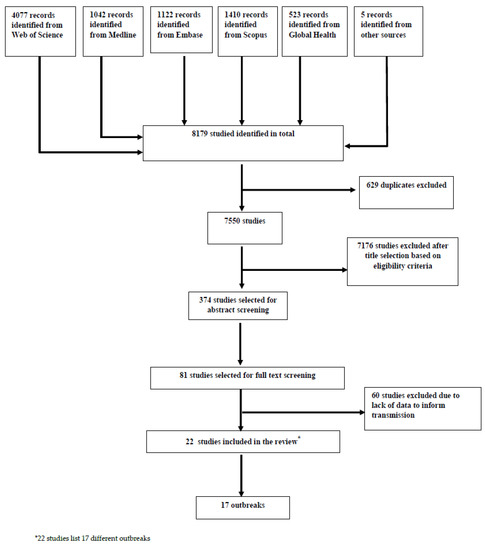

A systematic review was conducted on finding evidence for aerial transmission of smallpox. Our review focused on identifying smallpox outbreaks occurring in humans and studying the reported transmission pattern to find evidence of aerial convection spread. Specifically, we looked for cases where people acquired smallpox in the vicinity of, but at a distance of >2 m from a known smallpox case. We searched five databases: Medline (1946 to present), Embase (1974 to present), Scopus (1960 to present), Web of Science (1898 to present), Global Health (1910 to present). Results were limited to peer-reviewed publications in English. Search terms used were “smallpox” OR “variola” AND “transmission” AND “outbreak”. We also reviewed the bibliography of retrieved articles to identify other references that might not otherwise have been identified. Secondary searches were conducted which included the cross-references from various relevant papers. Author AD independently screened each title and abstract in the search result and in case of uncertainty, the author (CRM) was consulted. A full-text evaluation was conducted by three review authors (CRM, AD and XC). The results from our review are presented in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, which is the accepted standard for a systematic review (Figure 1) [34].

Figure 1.

Search process for systematic review [34].

2.3. Selection Criteria and Inclusion

We focused on the aerial transmissibility of smallpox in outbreaks and on the evidence of transmission route from analysis of relevant outbreaks. Eligible studies had to fulfil the following criteria: (1) Peer-reviewed journal articles, (2) published in English, (3) primary focus on smallpox outbreaks in humans, (4) outbreak case studies showing evidence of transmission at distances >2 m in the absence of known smallpox transmission in the surrounding community, (5) studies on variola major or variola minor.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Following the full-text assessment, we excluded (1) an outbreak or case of smallpox acquired where the acquired case was in close proximity (within a distance of 2 m) of a known case of smallpox, enabling direct respiratory transmission by droplets or aerosols, or through physical contact, or where the outbreak occurred in the presence of known smallpox transmission in the surrounding community, making transmission too widespread to observe long-distance transmission. (2) Laboratory experiments and studies unrelated to transmission route of smallpox, (3) non-human studies, (4) mathematical modelling studies, (5) studies focussing on smallpox eradication or vaccination, and (6) studies focusing on vaccinia virus.

2.5. Review

Firstly, we read all titles and abstracts of the studies identified through the search and after removing duplicates, we included relevant, eligible papers for full-text assessment studies. While considering the contributory role of airborne transmission of smallpox, we assumed that fulfillment of the following conditions indicated evidentiary support [17].

An outbreak or case of smallpox in a setting that occurred due to transmission of infectious particles from one location to another spatially separate location, farther than possible through direct person to person respiratory transmission (>2 m) and without evidence of other community transmissions that could have explained incident infections. The term “aerial convection” (used in the pre-eradication era) was used for distant transmission.

All the review authors were asked to consider these criteria while rating the findings of each study as “Conclusive” if aerial convection was the only explanation for one or more transmissions or “Partially conclusive” if aerial convection was one explanation for one or more transmissions, but other explanations were also possible [35].

3. Results

We identified 22 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, which described 17 different outbreaks. The outbreaks with evidence of transmission route from the selected studies are summarized in Table 1. Eight outbreaks involved very long-range transmission beyond a single building or location and nine involved transmission within a building that could not be explained by direct person to person contact. This included two outbreaks where transmission occurred vertically from one floor to another floor of a building.

Table 1.

Outbreaks providing evidence of aerial transmission of smallpox.

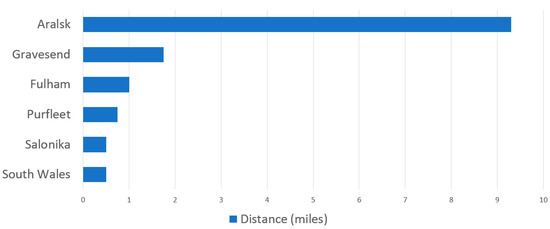

Figure 2 summarises the distances of aerial convection of smallpox in different outbreaks described in Table 1, where distance was quantified. This ranged from half a mile (0.8 km) to over 9 miles (15 km) in the case of the Aralsk outbreak. Most were between 0.5–1 mile (0.8–1.6 km).

Figure 2.

Maximum reported distance (miles) of aerial convection of smallpox in different outbreaks, where distance was quantified.

Figure 3 shows the epidemiology of smallpox cases in London and the window during which aerial convection was observed, which was in a period of the very low incidence of infection, from 1881 to 1978, two years before eradication.

Figure 3.

Number of smallpox deaths 1700–1980, London—period of observation of aerial convection shown in two-sided horizontal arrow.

The outbreaks we studied showed two different patterns of transmission. One was of very long-range transmission over distances of a half-mile to a mile. This comprised single source cases and a secondary case occurring at a long horizontal distance, or clustering of cases in the community within a radius around a smallpox hospital (building or ship). The second was transmission within a building (often vertically from one floor to another) or between adjacent buildings in the absence of relevant contact with an infected case. The Birmingham case [27,28], the Meschede outbreak [9,10,11,17,41,42,49] and the New York outbreak [39] showed transmission from one floor of a building to another, suggesting air currents can carry virus either through the air conditioning systems or through open windows. One study supporting aerial convection of variola is the controlled experimental work conducted in the Meschede, Germany outbreak via smoke flow visualisation [9,10,49]. These results clearly revealed that the airflow patterns matched the location of cases within buildings. At the time, however, such studies were limited, and emphasis was placed on trying to explain transmission by other modes of transmission.

The second pattern was long-distance horizontal transmission from one site to another of a mile or more, as seen in Fulham [8,36], Salonika [37], Gravesend [37], and Purfleet [8], among others. The Fulham data are particularly convincing because of the painstaking collection of data and mapping of smallpox cases in proximity to hospitals, and the fact that the initial observations in Fulham were reproduced around the country. [8,36] The observations from the smallpox ships in the Thames and recurrent epidemics in the nearest communities to shore were also supportive. An outlier case was that of the Lev Berg ship in the Aral sea. In this instance, it is likely that the official reports (which state the index case got off the ship at several stops) was an obfuscation of the truth, and that the comments of Dr Pyotr Burgasov after the collapse of the Soviet Union (that a 400 g smallpox “bomb” was exploded on Vozrozhdeniye Island) were closer to the truth [50]. The Lev Berg sailed 15 km off the coast of Vozrozhdeniye Island, which was a known Soviet biological weapon testing site. It seems likely this was the source of infection, and possible that a weaponised attack may disperse the virus at least 15 km.

4. Discussion

Understanding smallpox transmission is crucial for preparedness planning and can inform control of a re-emergent epidemic of smallpox. It was accepted that variola was most effectively transmitted by the respiratory route, and it was formerly called a “preferentially” airborne infectious disease” [51]. Variola virus has been recovered in airborne droplets from air sampling, supporting aerosol transmission [20]. The observation of aerial convection in a number of outbreaks further supports airborne transmission. Aerial convection, however, was more controversial and is not a concept that is currently in the corporate memory or included in hospital infection control protocols. We found supportive evidence of aerial convection from 12 out of 17 outbreaks, and a further 5 outbreaks which were partially conclusive. The examples of transmission from one floor to another or one building to another, presumably by air currents, are more easily explained, as distances were shorter and supported by the smoke experiments at Meschede, Germany [9,10,49]. In the last documented case of smallpox in the world, the Birmingham case, we can be fairly certain the patient was infected from a virus in the laboratory. Case ascertainment was high at that time, the location was the UK, which had long since eliminated smallpox, so it is likely the source of infection was an aerosolised virus through air-conditioning dust or an open window. More recently, the transmission of SARS in the Amoy Gardens building, where aerosolised faecal material spread from floor to floor through plumbing and open bathroom grates, but also from open windows to adjacent buildings, demonstrated that air currents can carry virus particles from one building to another [52]. However, in over half of the outbreaks we reviewed, there were reports of infections from a single index patient that were between a quarter to one mile apart in the absence of other smallpox cases in the community. At such distances, other modes of transmission are largely infeasible, although secondary aerosolization from contaminated clothing or bedlinen carried from the patient room to the community is possible. Another possibility in the apparently long-range transmissions is that these were exposed to missed mild or vaccine-modified cases. However, it should be noted in the case in Greece, that the secondary case occurred within the incubation period of the index case being symptomatic [37].

The theory of aerial convection is biologically plausible. Several studies in humans and animals have shown that virus concentration is higher in the lower respiratory tract than the upper respiratory tract and that the infectious dose is very low, consistent with smaller airborne infectious particles from the lower respiratory tract being the source of infection transmission from smallpox patients [8]. In fact, asymptomatic contacts have been documented to have variola in the oropharynx, but are not infectious and only a minority go on to develop smallpox [53]. This suggests that transmission of infection occurs preferentially with a lower respiratory infection, which would generate fine airborne infectious particles [8].

It should be noted that the theory of aerial convection was first proposed in England in 1881 following the observations around Fulham and that the data collected since then was in an era of rapidly declining incidence of disease, well after compulsory smallpox vaccination in the country in the mid-1800s. It is likely that prior to routine vaccination, transmission in the community was too widespread and intense to observe unusual patterns of aerial transmission from a single case to others. If there were many cases in a community, any incident cases would be attributed to close proximity transmission. It was only in the period of decline in the incidence of smallpox that the phenomenon became apparent because explanatory source cases in the community were largely absent. During the 100 years leading up to eradication, the low incidence of smallpox made it easier to observe unusual transmissions from single cases, and exclude close contact with a known case. There was, therefore, a limited window to collect data before smallpox became exceedingly rare in England [8]. Whilst the theory was debated and disputed, including the role of climatic wind conditions in the dispersion of smallpox by air, by 1904 more experts were in favour of aerial convection than against. However, by this time smallpox became too rare to collect ongoing outbreak data, and we are left only with the data from documented outbreaks between 1881 and 1971 [8]. Other than the systematic analysis of data attempted in England in the late 19th century, we are left with evidence from the individual outbreaks reviewed in this study.

In 1886, Sir George Buchannan addressed the Epidemiologic Society of England on the topic of aerial convection of smallpox: “We cannot get away from these facts; they are as definite as any known to epidemiology. They had already been ascertained by a multiplicity of careful and detailed observations, in many hospitals, in different epidemics, in London and the Provinces. Recent epidemics have now enabled the question to be tested afresh. That smallpox hospitals have had a deleterious influence in disseminating the disease in surrounding areas is now admitted, so there is no need for this aspect of the case to be argued further, but it is noteworthy that with no other disease has a similar influence been established. In this respect, smallpox stands alone, which proves that its infectivity is exceptional” [8]. The uniqueness of smallpox transmission in contrast to other infections is the striking point made. There are alternative explanations to cases occurring within the incubation period of theoretical exposure to a distantly located primary case. In the Purfleet examples, some experts felt that staff were visiting the communities onshore in secret, possibly carrying with them contaminated clothing or bedding. It was also postulated in Fulham and the rest of the English hospitals that the rings of infection around the buildings were due to movement of staff wearing contaminated clothing. Secondary aerosolization of virus from scabs or other bodily secretions on clothing is possible. The hospital staff, if immune, could conceivably carry fragments of scabs on their clothing which could infect susceptible community contacts whilst the staff themselves remained well. It was documented that smallpox particles are extraordinarily resistant to inactivation by drying (low humidity conditions) and if not exposed to direct sunlight, can remain within dust particles for long periods of time (54,55). If this is the case, isolated single cases could occur by re-aerosolisation of scab material on clothing or bedding. One study in 1957 showed that scabs from smallpox patients could contain the viable virus for 18 months, and for years if the scabs were kept in bottles [54]. In a later study in 1967, Wolff and Croon showed that in dried crusts from skin lesions of variola minor, the virus can remain viable for at least 13 years at room temperature [55].

5. Conclusions

In summary, the evidence from these outbreaks is supportive of aerial convection of smallpox at distances of more than a mile in some cases and is biologically plausible due to higher concentration of virus in the lower respiratory tract, environmental factors such as wind, and the low infectious dose. In addition, in many of the observed long-range transmissions, there was a temporal association between potential exposure to a known case and illness. It is possible, that some cases of smallpox were “super-spreaders” with much higher viral shedding than others. This has been seen with other viral respiratory pathogens such as SARS. If this is the case, super-spreaders could explain long-range transmission.

The theory of aerial convection arose in the period of decline in smallpox incidence in the UK, as the rarity of the disease made it possible to notice unusual transmissions in the absence of close contact. This small window of opportunity for studying aerial convection then rapidly closed, as smallpox became extremely rare in the UK by the early 20th century. This may, in part, explain the loss of this disease transmission theory from current infection control policy and practice, but potentially places smallpox in a different category from other known respiratory transmissible infections. In modern hospitals in high-income countries, negative pressure isolation rooms would reduce any risk of aerial convection. Other explanations for apparent aerial convection are possible, including missed chains of transmission, fomite transmission and secondary aerosolization of contaminated materials such as bed linen. Should smallpox re-emerge, awareness of the possibility of aerial convection is important, as it could inform planning for smallpox treatment facilities and protecting hospitals and surrounding communities.

Author Contributions

C.R.M.: Conceived and designed the study, reviewed abstracts, assisted with screening and selection of relevant studies, reviewed and interpreted each selected study, designed the data analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript. A.D.: reviewed all potentially relevant papers to determine those which met the selection criteria, initial draft of the literature review. X.C.: reviewed all potentially relevant papers to determine those which met the selection criteria, data collection and analysis. C.D.S. and C.D.: reviewed the evidence from selected studies and contributed to manuscript revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC), Centres of Research Excellence (CRE) grant (APP1107393). C Raina MacIntyre is supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship, grant number 1137582.

Conflicts of Interest

C Raina MacIntyre has received funding from Emergent Biosolutions, SIGA Technologies, Meridien Medical Technology and Bavarian Nordic to support an investigator-designed table top exercise on smallpox re-emergence. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests and have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

References

- Melamed, S.; Israely, T.; Paran, N. Challenges and Achievements in Prevention and Treatment of Smallpox. Vaccines 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenner, F. A successful eradication campaign. Global eradication of smallpox. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1982, 4, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Kunasekaran, M.P.; Costantino, V.; MacIntyre, C.R. How Valid Are Assumptions About Re-emerging Smallpox? A Systematic Review of Parameters Used in Smallpox Mathematical Models. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, R.; Leach, S. Transmission potential of smallpox in contemporary populations. Nature 2001, 414, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Medical Association. WHO marks 25th anniversary of last naturally acquired smallpox case. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2002, 167, 1278. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; Costantino, V.; Kunasekaran, M.P. Health system capacity in Sydney, Australia in the event of a biological attack with smallpox. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 0217704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; Chughtai, A.A.; Seale, H.; Richards, G.A.; Davidson, P.M. Respiratory protection for healthcare workers treating Ebola virus disease (EVD): Are facemasks sufficient to meet occupational health and safety obligations? Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, C.K. Aerial convection from smallpox hospitals. Br. Med. J. 1944, 1944, 628–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Airborne Transmission of Smallpox. Br. Med. J. 1970, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anonymous. Airborne transmission of smallpox. South. Med. J. 1971, 64, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Airborne transmission of smallpox. Who Chron. 1970, 24, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Nicas, M.; Hubbard, A.E.; Jones, R.M.; Reingold, A.L. The Infectious Dose of Variola (Smallpox) Virus. Appl. Biosaf. 2004, 9, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, J.C.; Boulter, E.A.; Bowen, E.T.; Maber, H.B. Experimental respiratory infection with poxviruses. I. Clinical virological and epidemiological studies. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1966, 47, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brinckerhoff, W.R.; Tyzzer, W.E. Studies upon the Reactions of Variola Virus to certain External Conditions: Part V. J. Med. Res. 1906, 14, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hahon, N. Smallpox and related poxvirus infections in the simian host. Bacteriol. Rev. 1961, 25, 459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.W.; Li, Y.; Eames, I.; Chan, P.K.; Ridgway, G.L. Factors involved in the aerosol transmission of infection and control of ventilation in healthcare premises. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 64, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Leung, G.M.; Tang, J.W.; Yang, X.; Chao, C.Y.H.; Lin, J.Z.; Lu, J.W.; Nielsen, P.V.; Niu, J.; Qian, H.; et al. Role of ventilation in airborne transmission of infectious agents in the built environment—A multidisciplinary systematic review. Indoor Air 2007, 17, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, T.C. Airborne Nosocomial Infection: A Contemporary Perspective. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 1994, 15, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayliffe, G.A.J.; Lowbury, E.J.L. Airborne infection in hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 1982, 3, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. Air sampling of smallpox virus. J. Hyg. 1974, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gralton, J.; Tovey, E.; McLaws, M.L.; Rawlinson, W.D. The role of particle size in aerosolised pathogen transmission: A review. J. Infect. 2011, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; Chughtai, A.A. Facemasks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Our World in Data. Deaths from Smallpox in London 1629–1902. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-from-smallpox-in-london (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Fenner, F.; Henderson, D.; Arita, I.; Ježek, Z.; Ladnyi, I. The incidence and control of smallpox between 1900 and 1958. In Smallpox and its Eradication; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988; Volume 330. [Google Scholar]

- Edwardes, E.J. A Concise History of Small-Pox and Vaccination in Europe; HK Lewis: London, UK, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Culley, A.R. The smallpox outbreak in south wales in 1962. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1963, 56, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Smallpox in Birmingham. Br. Med. J. 1978, 2, 837. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. UK smallpox research could continue at Porton. Nature 1979, 277, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- A Vision of Britain through Time. 1911 Census of England and Wales: Population. Available online: http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1911GEN/3 (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Council on foreign relations. Smallpox. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/smallpox (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Fenner, F.; Henderson, D.A.; Arita, I.; Jezek, Z.; Ladnyi, I.D. Smallpox and its Eradication; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- A Vision of Britain through Time. 1921 Census of England and Wales: Population. Available online: http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1921GEN/3 (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Public Data. Available online: https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=jqd8iprpslrch_&met_y=pop&idim=country:GB&hl=en&dl=en (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, P.P. Ridding London of smallpox: The aerial transmission debate and the evolution of a precautionary approach. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008, 136, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, P.G. Aerial convection from smallpox hospitals. Br. Med. J. 1944, 1944, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Picken, R.M.F.; Harries, E.H.R.; Easton, P.G. Aerial Convection from Smallpox Hospitals. Br. Med. J. 1944, 1, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weinstein, I. An outbreak of smallpox in New-York-City. Am. J. Public Health 1947, 37, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.A. Outbreak of smallpox in a hospital. N. Engl. J. Med. 1950, 242, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, P.F.; Posch, J.; Richter, K.H.; Henderson, D.A. An airborne outbreak of smallpox in a German hospital and its significance with respect to other recent outbreaks in Europe. Bull. World Health Organ. 1970, 43, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.K. The epidemiological observations made in the two smallpox outbreaks in the land of Northrhine-Westphalia, 1962 at Simmerath (Eifel region) and 1970 at Meschede. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1971, 64, 775–777. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, W.H. Smallpox in England and wales 1962. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1963, 56, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangili, A.; Gendreau, M.A. Transmission of infectious diseases during commercial air travel. Lancet 2005, 365, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzinger, F.R. Disease Transmission by Aircraft; USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC): Brooks Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Withers, M.R.; Christopher, G.W. Aeromedical evacuation of biological warfare casualties: A treatise on infectious diseases on aircraft. Mil. Med. 2000, 165, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterbe, B.; Ringertz, O.; Svedmyr, A.; Wallmark, G. Epidemiology of smallpox in Stockholm 1963. Acta Med. Scand. 1966, 180, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, I.; Shafa, E.; Kader, A. Role of hospital in smallpox outbreak in Kuwait. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1970, 60, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gelfand, H.M.; Posch, J. The recent outbreak of smallpox in Meschede, West Germany. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1971, 93, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelicoff, A.P. An epidemiological analysis of the 1971 smallpox outbreak in Aralsk, Kazakhstan. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 29, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, D.K. What was the primary mode of smallpox transmission? Implications for biodefense. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, K.R.; Gong, Y.Y.; Lewis, T.G. Environmental transmission of SARS at Amoy Gardens. J. Environ. Health 2006, 68, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, J.K.; Mitra, A.C.; Mukherjee, M.K.; De, S.K. Virus excretion in smallpox. 2. Excretion in the throats of household contacts. Bull. World Health Organ. 1973, 48, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, F.; McDonald, J. Survival of variola virus in raw cotton. Bull. World Health Organ. 1957, 16, 247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolff, H.L.; Croon, J. The survival of smallpox virus (variola minor) in natural circumstances. Bull. World Health Organ. 1968, 38, 492. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).