Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

2.2. Species Identification

2.3. Diet Identification

2.4. RNA Extraction

2.5. RNA Sequencing and rRNA Depletion

2.6. Library Construction

2.7. Library Sequencing

2.8. Bioinformatic Analyses

2.9. Polymerase Chain Reactions

2.10. Genetic Analyses

2.11. GenBank Accession Numbers

3. Results

3.1. Diet Composition

3.2. Sequencing Results

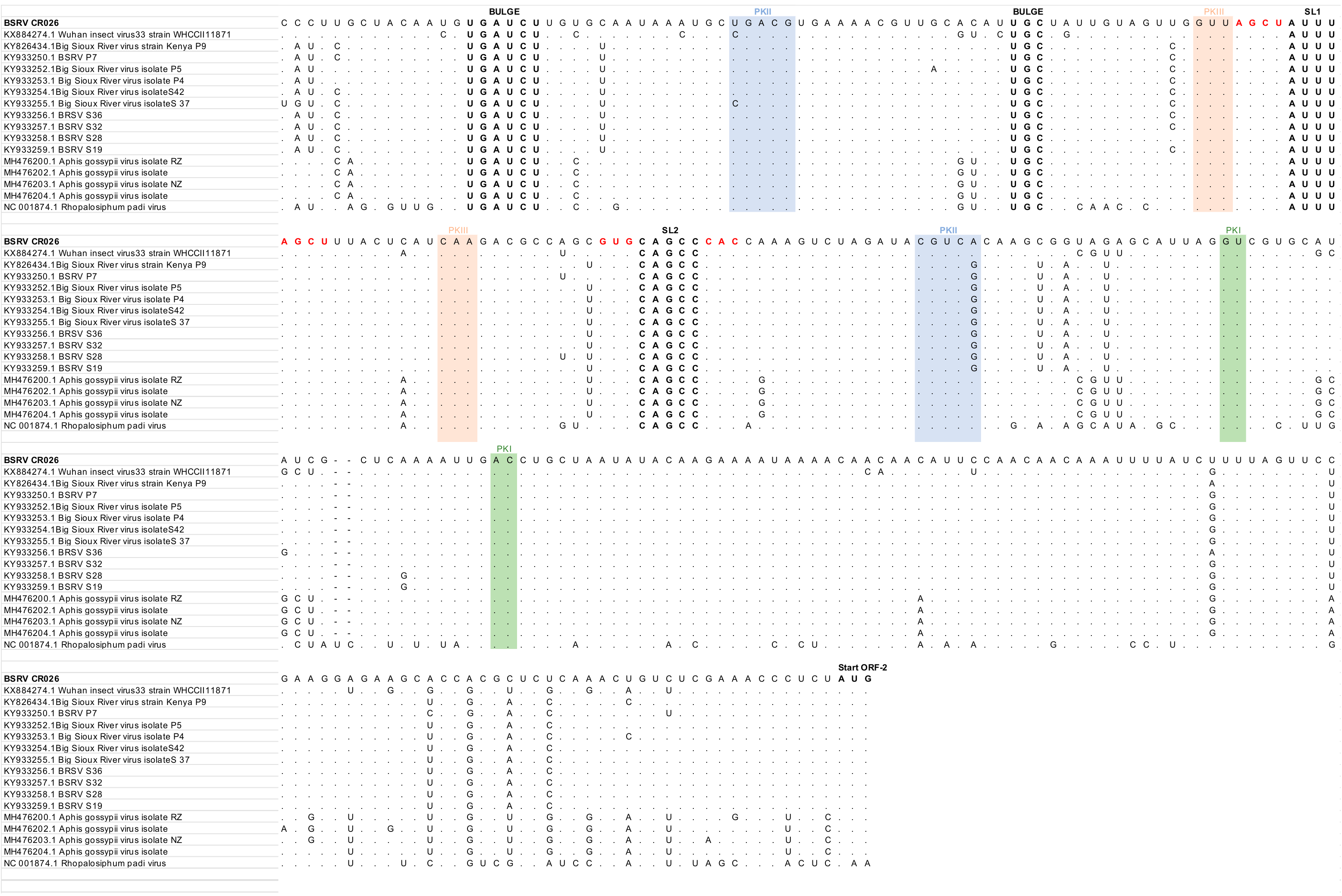

3.3. Genome Recovery

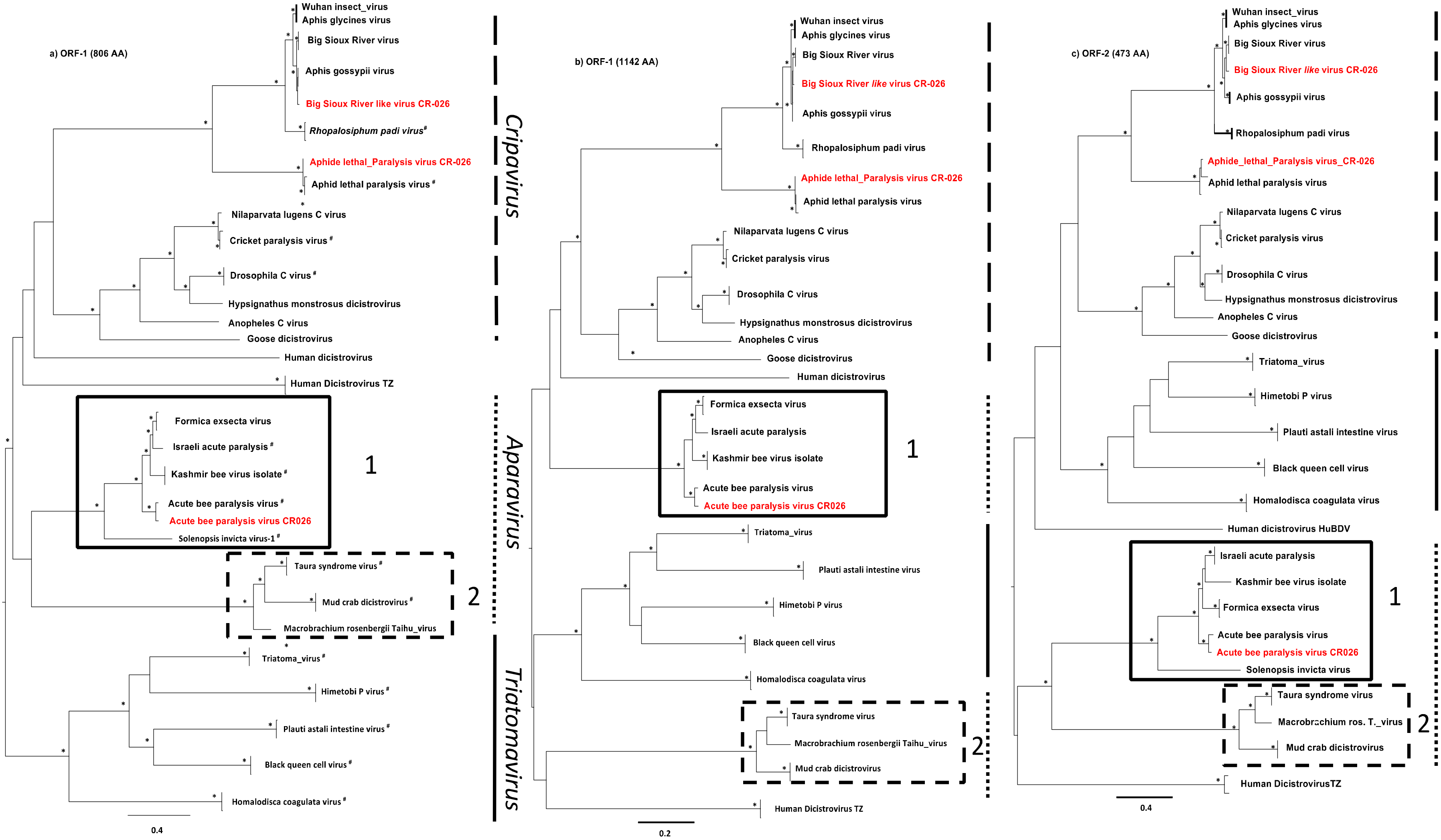

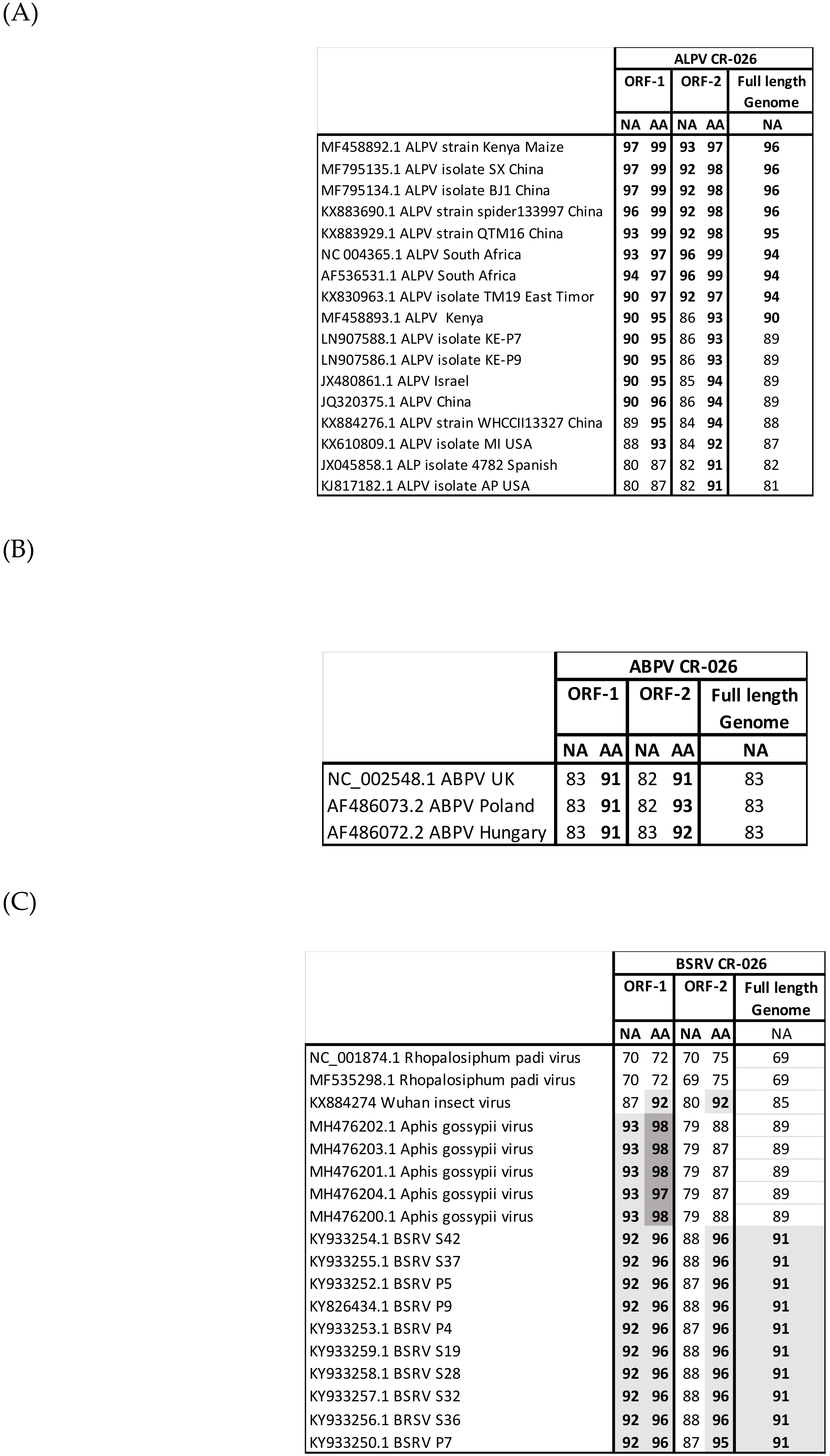

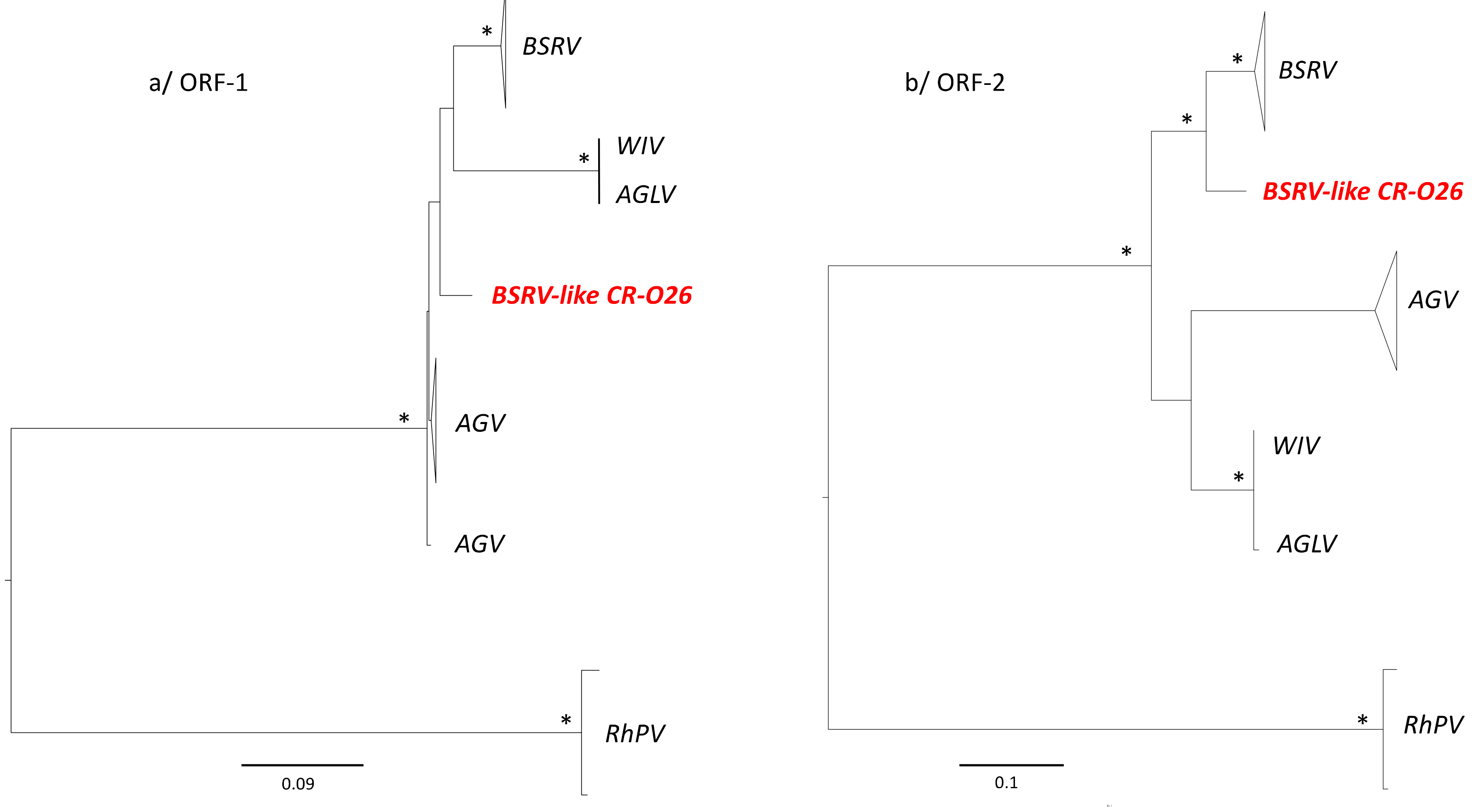

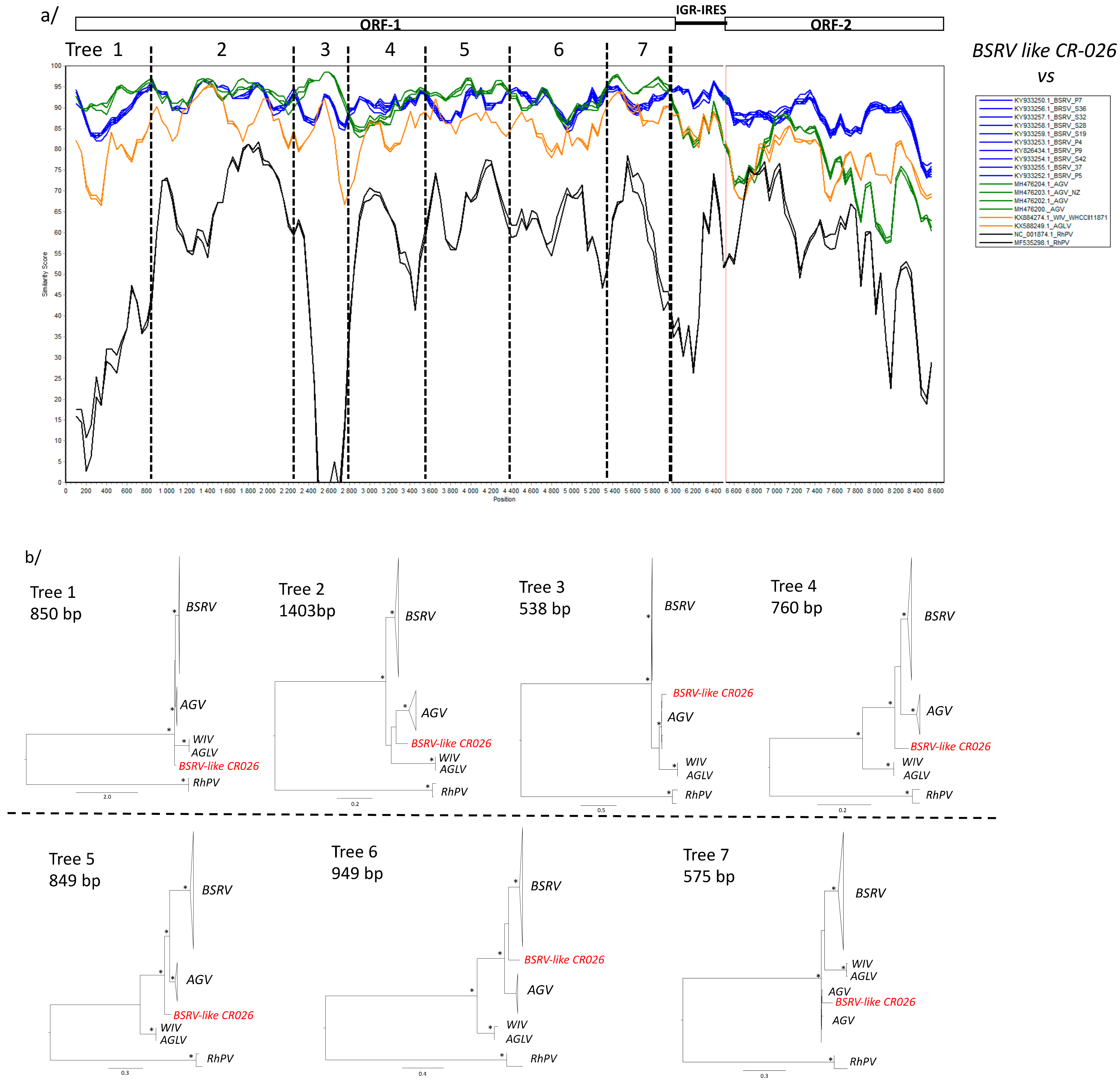

3.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jan, E. Divergent IRES elements in invertebrates. Virus Res. 2006, 119, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valles, S.M.; Chen, Y.; Firth, A.E.; Guérin, D.M.A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Herrero, S.; de Miranda, J.R.; Ryabov, E. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Dicistroviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonning, B.C.; Miller, W.A. Dicistroviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox-Foster, D.L.; Conlan, S.; Holmes, E.C.; Palacios, G.; Evans, J.D.; Moran, N.A.; Quan, P.L.; Briese, T.; Hornig, M.; Geiser, D.M.; et al. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science 2007, 318, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.X.; He, J.G.; Xu, H.D.; Weng, S.P. Pathogenicity and complete genome sequence analysis of the mud crab dicistrovirus-1. Virus Res. 2013, 171, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, K.W.; Lightner, D.V.; Poulos, B.T.; Redman, R.M.; White, B.L.; Brock, J.A.; Bonami, J.R. Taura syndrome in Penaeus vannamei: Demonstration of a viral etiology. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1995, 23, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Cao, Z.; Yuan, J.; Shi, Z.; Yuan, X.; Lin, L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, J.; Hao, G.; Shen, J. Isolation and characterization of a novel dicistrovirus associated with moralities of the great freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantillo, G.; Bottaro, M.; Di Pinto, A.; Martella, V.; Di Pinto, P.; Terio, V. Virus infections of honeybees Apis Mellifera. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2015, 4, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culley, A.I.; Lang, A.S.; Suttla, C.A. Metagenomic analysis of coastal RNA virus communities. Science 2006, 312, 1795–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, J.G.; Kapoor, A.; Li, L.; Blinkova, O.; Slikas, B.; Wang, C.; Naeem, A.; Zaidi, S.; Delwart, E. Metagenomic analyses of viruses in stool samples from children with acute flaccid paralysis. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4642–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomariz-Zilber, E.; Thomas-Orillard, M. Drosophila C virus and Drosophila hosts: A good association in various environments. J. Evol. Biol. 1993, 6, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamonje, F.O.; Michuki, G.N.; Braidwood, L.A.; Njuguna, J.N.; Musembi Mutuku, J.; Djikeng, A.; Harvey, J.J.W.; Carr, J.P. Viral metagenomics of aphids present in bean and maize plots on mixed-use farms in Kenya reveals the presence of three dicistroviruses including a novel Big Sioux River virus-like dicistrovirus. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcy, C.J.; Burnett, P.A.; Hewings, A.D. Detection, biological effects, and transmission of a virus of the aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Virology 1981, 114, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfill, S.J.; Williamson, C.; Kirby, R.; von Wechmar, M.B. Identification and localization of aphid lethal paralysis virus particles in thin tissue sections of the Rhopalosiphum padi aphid by in situ nucleic acid hybridization. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1990, 55, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinganum, C.; O’Loughlin, G.T.; Hogan, T.W. A nonoccluded virus of the field crickets Teleogryllus oceanicus and T. commodus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1970, 16, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remnant, E.J.; Mather, N.; Gillard, T.L.; Yagound, B.; Beekman, M. Direct transmission by injection affects competition among RNA viruses in honeybees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimo, G.; Eiglmeier, K.; Reveillaud, J.; Holm, I.; Diallo, M.; Diallo, D.; Vantaux, A.; Kim, S.; Ménard, D.; Siv, S.; et al. Identification and characterization of two novel RNA viruses from Anopheles gambiae species complex mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Krueger, E.N.; Liu, S.; Dorman, K.; Bonning, B.C.; Miller, W.A. Discovery of known and novel viral genomes in soybean aphid by deep sequencing. Phytobiomes J. 2017, 1, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasu, E.Y.T.; Hedil, M.; Nagata, T.; Michereff-Filho, M.; Lucena, V.S.; Inoue-Nagata, A.K. Complete genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a novel dicistrovirus associated with the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Virus Res. 2019, 260, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.K.; Anderson, D.L.; Durr, P.A. Metagenomic analysis of Varroa-free Australian honey bees (Apis mellifera) shows a diverse Picornavirales virome. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runckel, C.; Flenniken, M.L.; Engel, J.C.; Ruby, J.G.; Ganem, D.; Andino, R.; DeRisi, J.L. Temporal analysis of the honey bee microbiome reveals four novel viruses and seasonal prevalence of known viruses, Nosema, and Crithidia. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z. A metagenomic survey of viral abundance and diversity in mosquitoes from hubei province. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraisamy, R.; Akiana, J.; Davoust, B.; Mediannikov, O.; Michelle, C.; Robert, C.; Parra, H.J.; Raoult, D.; Biagini, P.; Desnues, C. Detection of novel RNA viruses from free-living gorillas, Republic of the Congo: Genetic diversity of picobirnaviruses. Virus Genes 2018, 54, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z. Metagenomic analysis of viruses from bat fecal samples reveals many novel viruses in insectivorous bats in China. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4620–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbholz, A.; Groth, M.; Esefeld, J.; Peter, H.-U.; Zelld, R. Genome sequence of a novel picorna- like RNA virus from feces of the antarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazella). Genome Annouc. 2017, 5, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, G.; Pankovics, P.; Gyöngyi, Z.; Delwart, E.; Boros, Á. Novel dicistrovirus from bat guano. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 3453–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Victoria, J.G.; Wang, C.; Jones, M.; Fellers, G.M.; Kunz, T.H.; Delwart, E. Bat guano virome: Predominance of dietary viruses from insects and plants plus novel mammalian viruses. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 6955–6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, S.; Shan, T.; Hou, R.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; et al. Virome comparisons in wild-diseased and healthy captive giant pandas. Microbiome 2017, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.J.; Bushmaker, T.; Cameron, K.; Ondzie, A.; Niama, F.R.; Parra, H.-J.; Mombouli, J.-V.; Olson, S.H.; Munster, V.J.; Goldberg, T.L. Diverse RNA viruses of arthropod origin in the blood of fruit bats suggest a link between bat and arthropod viromes. Virology 2019, 528, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordey, S.; Laubscher, F.; Hartley, M.-A.; Junier, T.; Pérez-Rodriguez, F.J.; Keitel, K.; Vieille, G.; Samaka, J.; Mlaganile, T.; Kagoro, F.; et al. Detection of dicistroviruses RNA in blood of febrile Tanzanian children. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.G.; Del Valle Mendoza, J.; Sadeghi, M.; Altan, E.; Deng, X.; Delwart, E. Sera of Peruvians with fever of unknown origins include viral nucleic acids from non-vertebrate hosts. Virus Genes 2015, 20, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgarel, M.; Pfukenyi, D.M.; Boué, V.; Talignani, L.; Chiweshe, N.; Diop, F.; Caron, A.; Matope, G.; Missé, D.; Liégeois, F. Circulation of Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Paramyxovirus in Hipposideros bat species in Zimbabwe. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocher, T.D.; Thomas, W.K.; Meyer, A.; Edwards, S.V.; Paabo, S.; Villablanca, F.X.; Wilson, A.C. Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: Amplification and sequencing with conserved primers (cytochrome b/12S ribosomal DNA/control region/evolutionary genetics/molecular phylogenies). Evolution (N. Y.) 1989, 86, 6196–6200. [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem, A.; Taylor, P.J.; Cotterill, F.P.D.; Schoeman, M.C. Bats of Southern and Central Africa: A Biogeographic and Taxonomic Synthesis; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010; ISBN 978-1-86814-508-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet, F.; Tiouchichine, M.-L.; Galan, M.; Blanc, F.; Némoz, M.; Aulagnier, S.; Michaux, J.R. A new method to identify the endangered Pyrenean desman (Galemys pyrenaicus) and to study its diet, using next generation sequencing from faeces. Mamm. Biol. 2015, 80, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriollo, T.; Gillet, F.; Michaux, J.R.; Ruedi, M. The menu varies with metabarcoding practices: A case study with the bat Plecotus auritus. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodacre, N.; Aljanahi, A.; Nandakumar, S.; Mikailov, M.; Khan, A.S. A Reference Viral Database (RVDB) to enhane bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput sequencing for novel virus detection. mSphere 2018, 3, e00069-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milne, I.; Lindner, D.; Bayer, M.; Husmeier, D.; Mcguire, G.; Marshall, D.F.; Wright, F. TOPALi v2: A rich graphical interface for evolutionary analyses of multiple alignments on HPC clusters and multi-core desktops. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; Mcgettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The barcode of life data system (www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valles, S.M.; Rivers, A.R. Nine new RNA viruses associated with the fire ant Solenopsis invicta from its native range. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, N.; Horth, L.; Al-Shagour, B.; Adjlane, N.; Loucif-Ayad, W. Next-generation sequence data demonstrate several pathogenic bee viruses in Middle East and African honey bee subspecies (Apis mellifera syriaca, Apis mellifera intermissa) as well as their cohabiting pathogenic mites (Varroa destructor). Virus Genes 2018, 54, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajobe, R.; Marris, G.; Budge, G.; Laurenson, L.; Cordoni, G.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, S.; Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Brown, M.A. First molecular detection of a viral pathogen in Ugandan honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 104, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjeddou, M.; Leat, N.; Allsopp, M.; Davison, S. Detection of acute bee paralysis virus and black queen cell virus from honeybees by reverse transcriptase PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2384–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Munster, M.; Dullemans, A.M.; Verbeek, M.; Van Den Heuvel, J.F.; Clérivet, A.; Van Der Wilk, F. Sequence analysis and genomic organization of Aphid lethal paralysis virus: A new member of the family Dicistroviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83 Pt 12, 3131–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govan, V.A.; Leat, N.; Allsopp, M.; Davison, S. Analysis of the complete genome sequence of acute bee paralysis virus shows that it belongs to the novel group of insect-infecting RNA viruses. Virology 2000, 277, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakonyi, T.; Grabensteiner, E.; Kolodziejek, J.; Rusvai, M.; Topolska, G.; Ritter, W.; Nowotny, N. Phylogenetic analysis of acute bee paralysis virus strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6446–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilmi, M.; Bradbear, N.; Mejia, D. Beekeeping and Sustainable Livelihoods; Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 9789251070628. [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin, A.J.; Flenniken, M.L. Recently identified bee viruses and their impact on bee pollinators. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emdem, H.F.; Harrington, R. (Eds.) Aphids as Crop Pests, 2nd ed.; CABI: Wallingfor, UK, 2017; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, C.; Rybicki, E.P.; Kasdorf, G.G.F.; Von Wechmar, M.B. Characterization of a new picorna-like virus isolated from Aphids. J. Gen. Virol. 1988, 69, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoda, M.; Upenyu, M.; Peter, C.; Susan, D. The response of the red morph of the Tobacco aphid, myzus persicae nicotianae, to insecticides applied under laboratory and field conditions. Asian J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2013, 3, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Belwood, J.J.; Fenton, M.B. Variation in the diet of Myotis lucifiugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Can. J. Zool. 1976, 54, 1674–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, R.M.R.; Brigham, R.M. Constraints on optimal foraging: A field test ofprey discrimination by echolo- cating insectivorous bats. Anim. Behav. 1994, 48, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, J.O.; Clem, P. Food of the evening bat Nycticeius humeralis from Indiana. Am. Midl. Nat. 1992, 127, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanjer-Wright, G. Hipposideros caffer (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae). Mamm. Species 2009, 845, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bourgarel, M.; Noël, V.; Pfukenyi, D.; Michaux, J.; André, A.; Becquart, P.; Cerqueira, F.; Barrachina, C.; Boué, V.; Talignani, L.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern. Viruses 2019, 11, 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11121102

Bourgarel M, Noël V, Pfukenyi D, Michaux J, André A, Becquart P, Cerqueira F, Barrachina C, Boué V, Talignani L, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern. Viruses. 2019; 11(12):1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11121102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBourgarel, Mathieu, Valérie Noël, Davies Pfukenyi, Johan Michaux, Adrien André, Pierre Becquart, Frédérique Cerqueira, Célia Barrachina, Vanina Boué, Loïc Talignani, and et al. 2019. "Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern" Viruses 11, no. 12: 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11121102

APA StyleBourgarel, M., Noël, V., Pfukenyi, D., Michaux, J., André, A., Becquart, P., Cerqueira, F., Barrachina, C., Boué, V., Talignani, L., Matope, G., Missé, D., Morand, S., & Liégeois, F. (2019). Next-Generation Sequencing on Insectivorous Bat Guano: An Accurate Tool to Identify Arthropod Viruses of Potential Agricultural Concern. Viruses, 11(12), 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11121102