Annual and Intra-Annual Variation in Lignin Content and Composition in Juvenile Pinus pinaster Ait. Wood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Sample Preparation

2.2. Analytical Pyrolysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analytical Pyrolysis Precision

3.2. Variability of Lignin Content and H/G Ratio Within and Between Rings

3.3. Variability of Lignin Pyrolysis Products Within and Between Rings

3.3.1. Lignin Pyrolysis Products

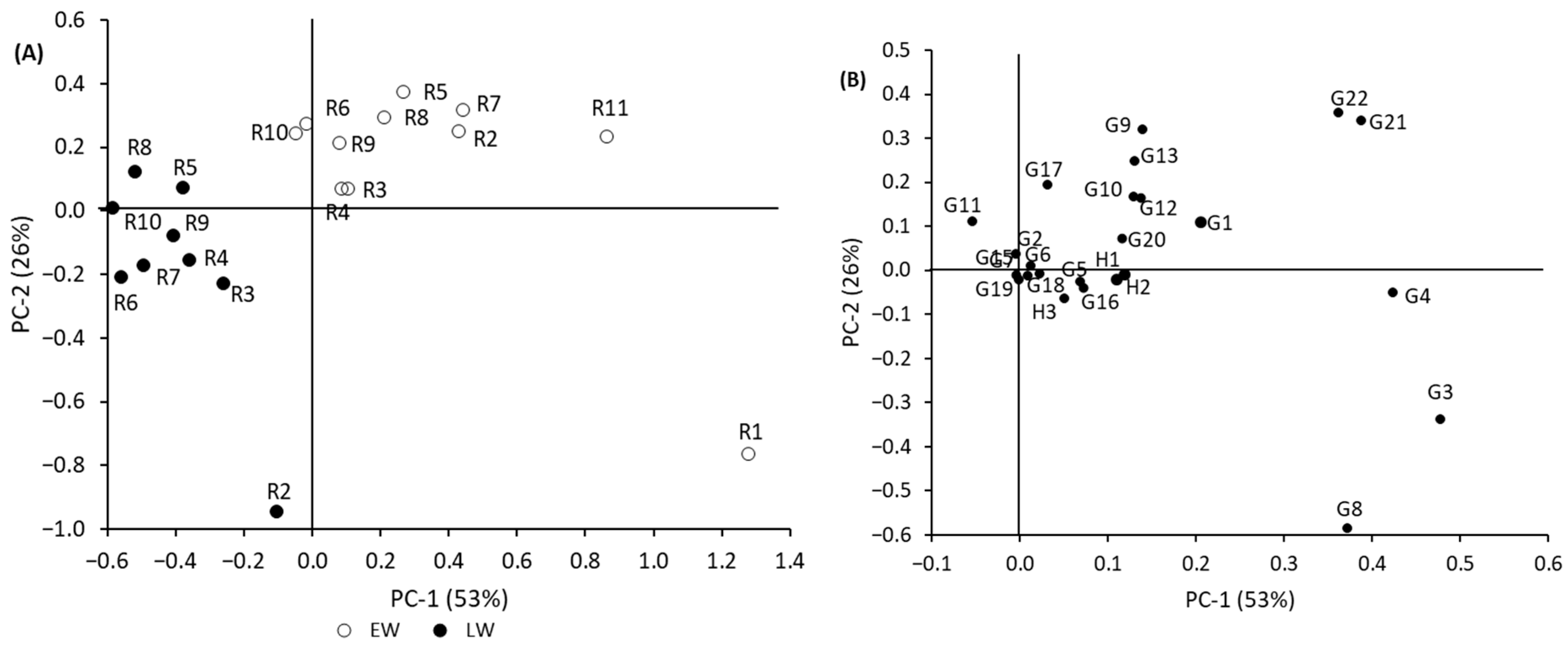

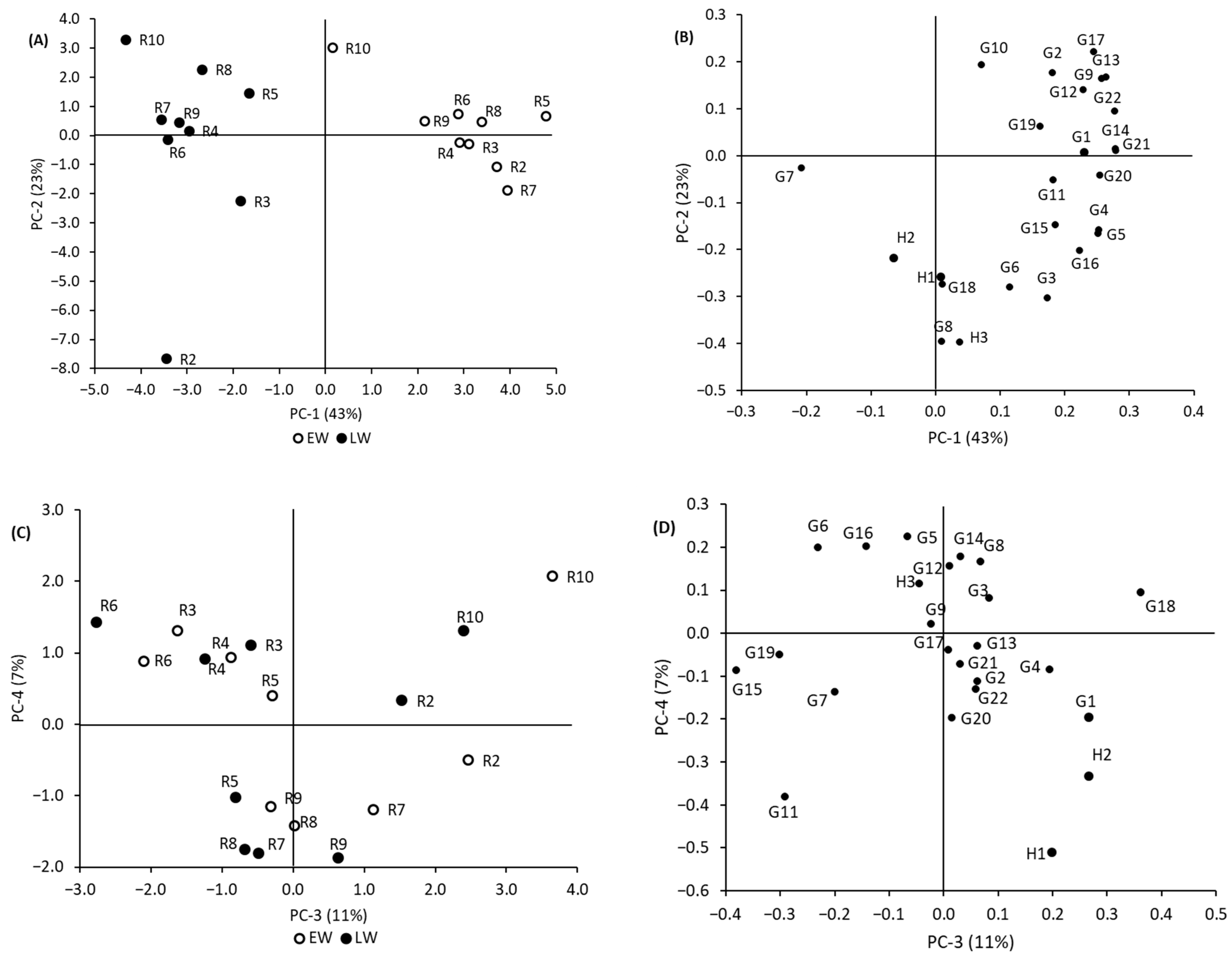

3.3.2. Mean-Centered PCA

3.3.3. Normalized PCA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruce, J.; Zobel, J.R.S. Juvenile Wood in Forest Trees; Springer Series in Wood Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cown, D.; Dowling, L. Juvenile wood and its implications. N. Z. J. For. 2015, 59, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zobel, B.J.; van Buijtenen, J.P. Wood Variation: Its Causes and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, M.; Pedersen, N.B.; Thygesen, L.G. The cell wall composition of Norway spruce earlywood and latewood revisited. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2018, 9, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, R.F. Xylem: Secondary Xylem and Variations in Wood Structure, in Esau’s Plant Anatomy; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L.A. Within, and between-tree variation in lignin concentration in the tracheid cell wall of Pinus radiata. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1985, 15, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, B.J.; Goring, D.A.I. The Distribution of Lignin in Birch Wood as Determined by Ultraviolet Microscopy. Holzforschung 1970, 24, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, J.; Rockel, B.; Lautner, S.; Windeisen, E.; Wanner, G. Lignin distribution in wood cell walls determined by TEM and backscattered SEM techniques. J. Struct. Biol. 2003, 143, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, K.; Imagawa, H. Quantitative-analysis of lignin using an UV microscopic image analyzer—Variation within one growth increment. Wood Sci. Technol. 1981, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucher, M.; Monties, B.; Montagu, M.V.; Boerjan, W. Biosynthesis and genetic engineering of lignin. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1998, 17, 125–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengel, D.; Wegener, G. Wood: Chemistry, Ultrastructure, Reactions; De Gruyter: Beijing, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Timell, T. Physiology of Compression Wood Formation, in Compression Wood in Gymnosperms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 1207–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.L. Lignins: Occurrence in woody tissues, isolation, reactions, and structure. In Wood Structure and Composition; Lewin, M., Goldstein, I.S., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 183–261. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, G.J.; Fleck, L.C. Chemistry of Wood: Springwood and Summerwood; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 1930.

- Kibblewhite, R.P.; Suckling, I.D.; Evans, R.; Grace, J.C.; Riddell, M.J. Lignin and carbohydrate variation with earlywood, latewood, and compression wood content of bent and straight ramets of a radiata pine clone. Holzforschung 2010, 64, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaud, F.; Holmbom, B. Chemical composition of earlywood and latewood in Norway spruce heartwood, sapwood and transition zone wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzopoulou, P.; Kamperidou, V. Chemical characterization of Wood and Bark biomass of the invasive species of Tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle), focusing on its chemical composition horizontal variability assessment. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, M.; Vinciguerra, V.; Silvestri, A. Heat treatment effect on lignin and carbohydrates in Corsican pine earlywood and latewood studied by PY-GC-MS technique. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2018, 38, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, G.F.; Varaksina, T.N.; Zheleznichenko, T.V.; Stasova, V.V. Lignin deposition during earlywood and latewood formation in Scots pine stems. Wood Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, G.F.; Varaksina, T.N.; Zheleznichenko, T.V.; Bazhenov, A.V. Changes in lignin structure during earlywood and latewood formation in Scots pine stems. Wood Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 927–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiyama, H.; Kojiro, K.; Okahisa, Y.; Imai, T.; Itoh, T.; Furuta, Y. Combined analysis of microstructures within an annual ring of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) by dynamic mechanical analysis and small angle X-ray scattering. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liszka, A.; Wightman, R.; Latowski, D.; Bourdon, M.; Krogh, K.B.R.M.; Pietrzykowski, M.; Lyczakowski, J.J. Structural differences of cell walls in earlywood and latewood of Pinus sylvestris and their contribution to biomass recalcitrance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1283093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutelje, J.; Eriksson, I. Analysis of Lignin in Fragments from Thermomechanical Spruce Pulp by Ultraviolet Microscopy. Holzforschung 1984, 38, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.M.; Goring, D.A.I. The Phenolic Hydroxyl Content of Lignin in Spruce Wood. Can. J. Chem. 1980, 58, 2411–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Gierlinger, N.; Schwanninger, M.; Rodrigues, J. Analytical pyrolysis as a direct method to determine the lignin content in wood Part 3. Evaluation of species-specific and tissue-specific differences in softwood lignin composition using principal component analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 85, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, D.; Faix, O. Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, in Methods in Lignin Chemistry; Lin, S.Y., Dence, C.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A.; Schwanninger, M.; Pereira, H.; Rodrigues, J. Analytical pyrolysis as a direct method to determine the lignin content in wood—Part 1: Comparison of pyrolysis lignin with Klason lignin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2006, 76, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Simões, R.; Lousada, J.L.; Lima-Brito, J.; Rodrigues, J. Predicting the lignin H/G ratio of Pinus sylvestris L. wood samples by PLS-R models based on near-infrared spectroscopy. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Graca, J.; Rodrigues, J. Analytical Pyrolysis as a Tool to Assess Residual Lignin Content and Structure in Maritime Pine High-Yield Pulp. Forests 2022, 13, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faix, O.; Meier, D.; Fortmann, I. Thermal-Degradation Products of Wood—A Collection of Electron-Impact (Ei) Mass-Spectra of Monomeric Lignin Derived Products. Holz Als Roh-Und Werkst. 1990, 48, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faix, O.; Meier, D.; Fortmann, I. Thermal-Degradation Products of Wood—Gas-Chromatographic Separation and Mass-Spectrometric Characterization of Monomeric Lignin Derived Products. Holz Als Roh-Und Werkst. 1990, 48, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, J.; Hatfield, R.D. Pyrolysis-GC-MS Characterization of forage materials. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1426–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Rodrigues, J. Variation of Eucalyptus globulus lignin content and composition within and between countries. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2025, 45, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, B.; Riddell, M.; Harrington, J. Screening of juvenile Pinus radiata wood by means of Py-GC/MS for compression wood focussing on the ratios of p-hydroxyphenyl to guaiacyl units (H/G ratios). Holzforschung 2016, 70, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio, F.; Baettyg, R.; Vergara, A.; Guerra, F.; Rozenberg, P. Genetic trends in wood density and radial growth with cambial age in a radiata pine progeny test. Ann. For. Sci. 2002, 59, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, E.I.; Adeosun, S.O. Sustainable Lignin for Carbon Fibers: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L.A. Lignification and lignin topochemistry—An ultrastructural view. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, L.A.; Singh, A.P.; Yoshinaga, A.; Takabe, K. Lignin distribution in mild compression wood of Pinus radiata. Can. J. Bot. -Rev. Can. Bot. 1999, 77, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, H. Lignin pyrolysis reactions. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Faix, O.; Meier, D. Characterization of residual lignins from chemical pulps of spruce (Picea abies L.) and beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) by analytical pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Holzforschung 2001, 55, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, K.; Nakagawa-izumi, A. Analytical pyrolysis of lignin: Products stemming from beta-5 substructures. Org. Geochem. 2006, 37, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, B.; Manley-Harris, M.; Suckling, I.D.; Donaldson, L.A. Quantitative chemical indicators to assess the gradation of compression wood. Holzforschung 2009, 63, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, R.; Sugiyama, J. A combined FT-IR microscopy and principal component analysis on softwood cell walls. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 52, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Chen, F.; Guo, D.; Parvathi, K. The biosynthesis of monolignols: A “metabolic grid”, or independent pathways to guaiacyl and syringyl units? Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terashima, N.; Fukushima, K. Heterogeneity in formation of lignin.11. An autoradiographic study of the heterogeneous formation and structure of pine lignin. Wood Sci. Technol. 1988, 22, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Py-Lignin (%) | H/G | |

| Ring nr. | EW–LW | EW–LW |

| R1 | 29.7–n.d. | 0.042–n.d. |

| R2 | 27.7–25.1 | 0.038–0.054 |

| R3 | 26.7–24.9 | 0.034–0.040 |

| R4 | 26.6–24.6 | 0.035–0.037 |

| R5 | 27.4–24.7 | 0.033–0.038 |

| R6 | 26.4–24.0 | 0.033–0.037 |

| R7 | 28.0–24.3 | 0.044–0.042 |

| R8 | 27.1–24.4 | 0.038–0.040 |

| R9 | 26.6–24.6 | 0.039–0.045 |

| R10 | 26.0–23.9 | 0.033–0.039 |

| R11 | 29.3–n.d. | 0.072–n.d. |

| Av. | 26.9–24.5 | 0.036–0.041 |

| Std | 0.6–0.4 | 0.004–0.006 |

| p-value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 |

| Code | Compound | EW * (%) | LW * (%) | EW ** (%) | LW ** (%) |

| H1 | Phenol | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| H2 | p-Cresol | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| H3 | m-Cresol | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| G1 | Guaiacol | 1.8 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 6.8 |

| G2 | 3-Methyl guaiacol | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| G3 | 4-Methyl guaiacol | 2.8 | 2.7 | 10.5 | 10.9 |

| G4 | 4-Vinyl guaiacol | 2.9 | 2.7 | 10.7 | 10.8 |

| G5 | Eugenol | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| G6 | 4-Propyl guaiacol | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| G7 | Isoeugenol (cis) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| G8 | Isoeugenol (trans) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 9.5 | 10.5 |

| G9 | Vanillin | 2.4 | 2.1 | 8.8 | 8.6 |

| G10 | Indene, 6-hydroxy-7-methoxy-, 1H- | 1.3 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| G11 | Indene, 6-hydroxy-7-methoxy-, 2H- | 0.8 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| G12 | Homovanillin | 1.4 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| G13 | Acetoguaiacone | 1.1 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| G14 | Guaiacyl acetone | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| G15 | Propioguaiacone | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| G16 | Isomer of coniferyl alcohol | 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| G17 | G-CO-CH=CH2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| G18 | G-CO-CO-CH3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| G19 | Dihydroconiferyl alcohol | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| G20 | Coniferyl alcohol (cis) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| G21 | Coniferyl alcohol (trans) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| G22 | Coniferylaldehyde | 3.1 | 2.7 | 11.4 | 11.0 |

| Total (%) | 26.9 | 24.5 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alves, A.; Graça, J.; Rodrigues, J. Annual and Intra-Annual Variation in Lignin Content and Composition in Juvenile Pinus pinaster Ait. Wood. Forests 2026, 17, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020164

Alves A, Graça J, Rodrigues J. Annual and Intra-Annual Variation in Lignin Content and Composition in Juvenile Pinus pinaster Ait. Wood. Forests. 2026; 17(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Ana, José Graça, and José Rodrigues. 2026. "Annual and Intra-Annual Variation in Lignin Content and Composition in Juvenile Pinus pinaster Ait. Wood" Forests 17, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020164

APA StyleAlves, A., Graça, J., & Rodrigues, J. (2026). Annual and Intra-Annual Variation in Lignin Content and Composition in Juvenile Pinus pinaster Ait. Wood. Forests, 17(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020164