Linking Forest Litter Bacterial and Fungal Diversity to Litter–Soil Interface Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Plot Setup and Sample Collection

2.3. Determination of Litter and Soil Chemical Properties

2.4. Litter Microbial Community Determination

2.5. Microbial Diversity Indices

- (1)

- Shannon

- (2)

- Chao 1

- (3)

- Simpson

- (4)

- PD whole tree

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Litter Microbial Community Diversity

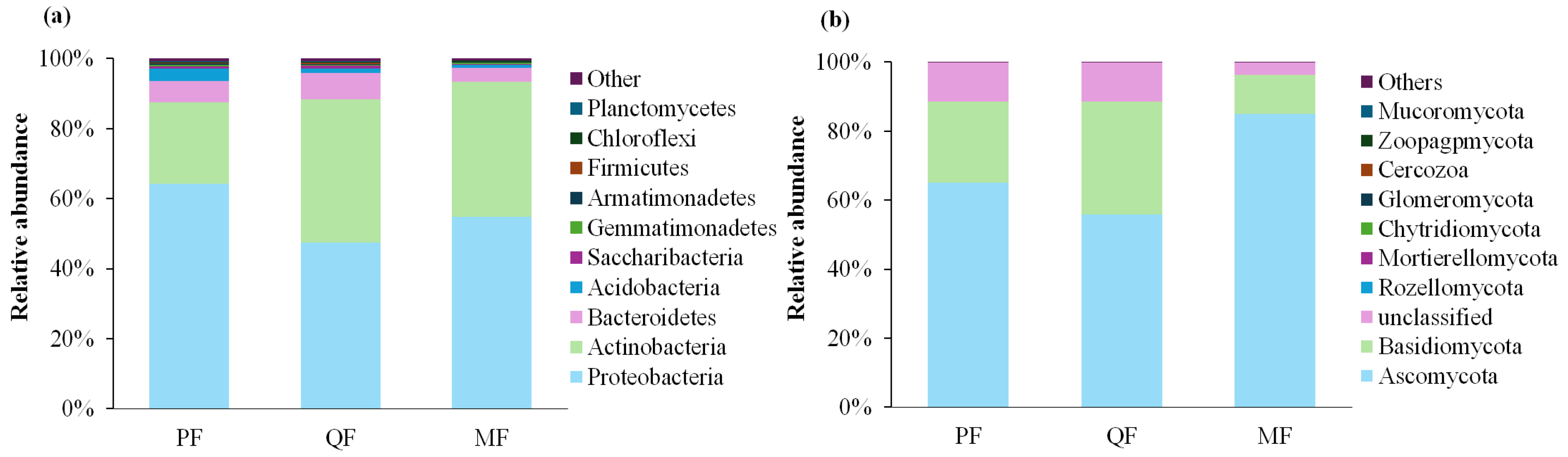

3.2. Litter Microbial Community Composition

3.3. Chemical Characteristics of Forest Litter and Soil

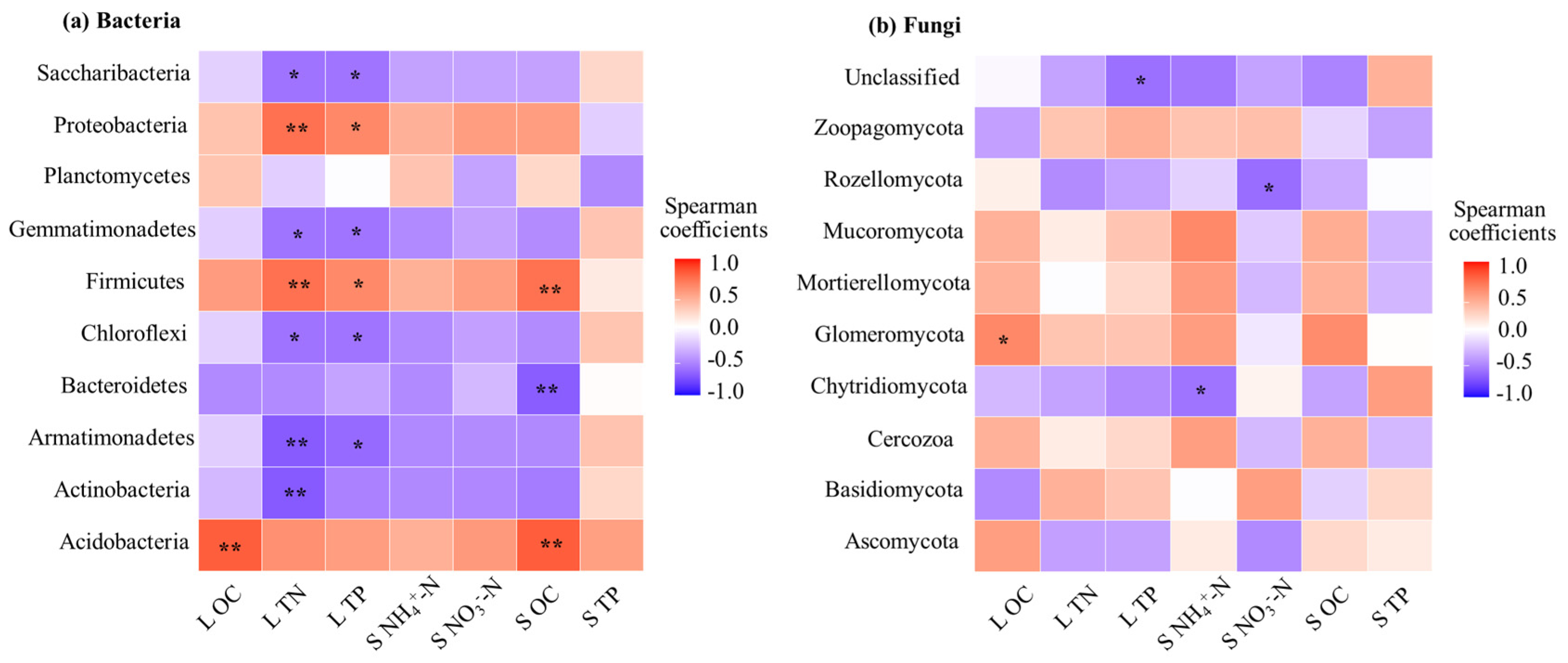

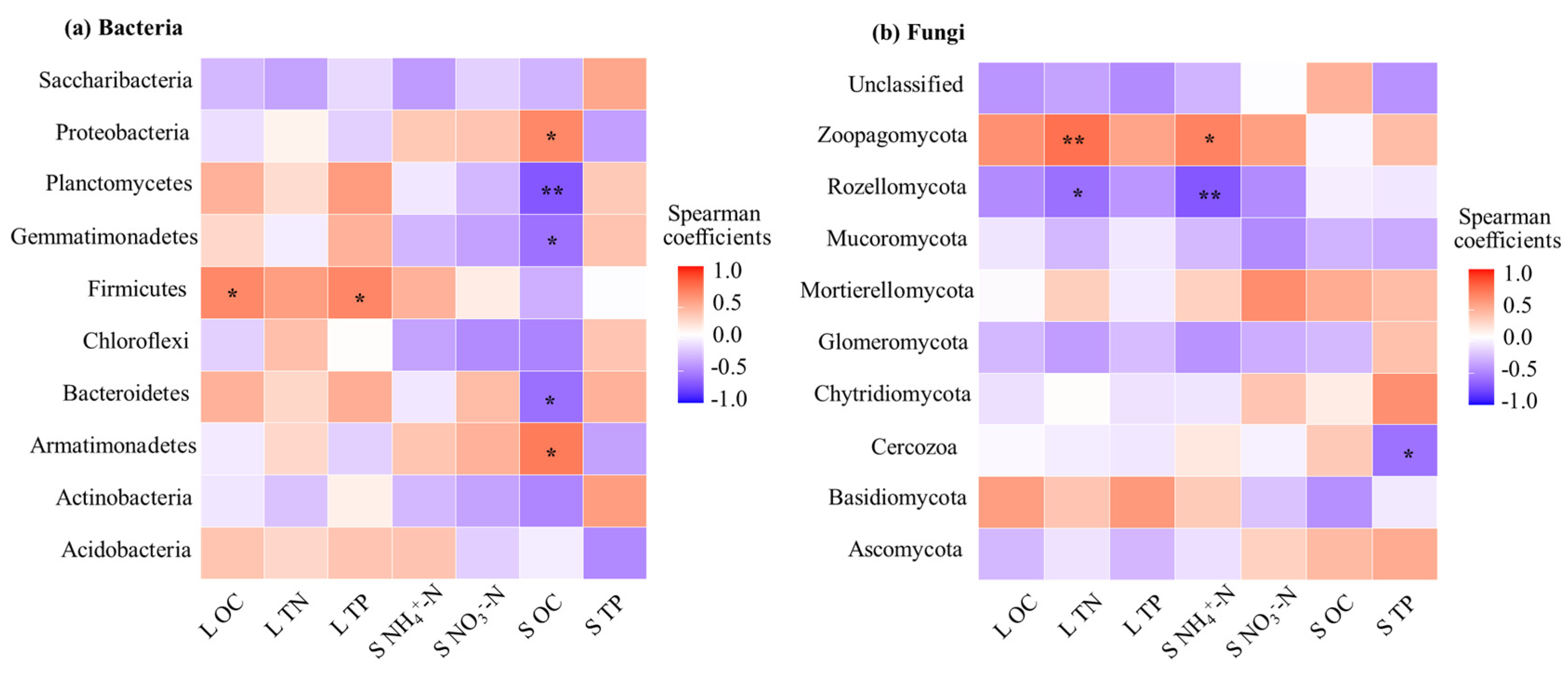

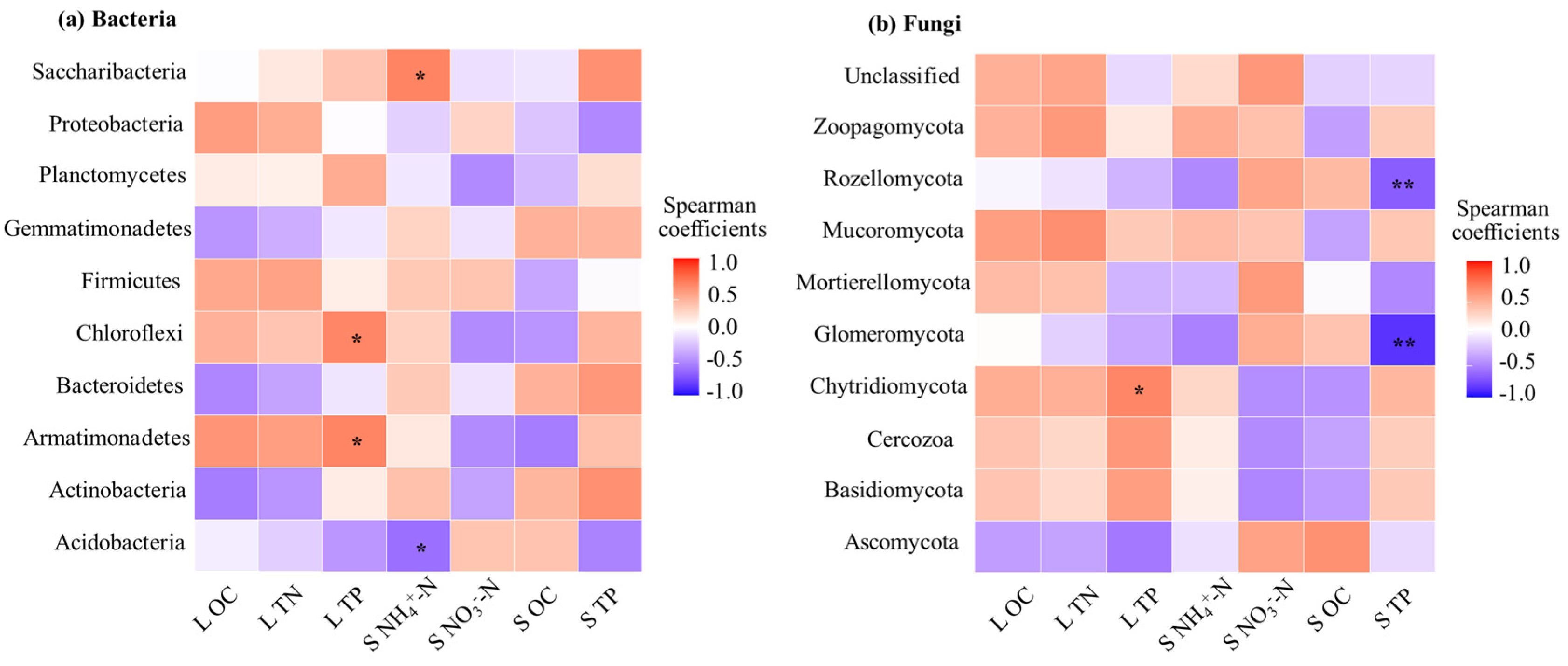

3.4. Correlation Between Litter Microbial Community Composition and Chemical Properties of Litter and Soil

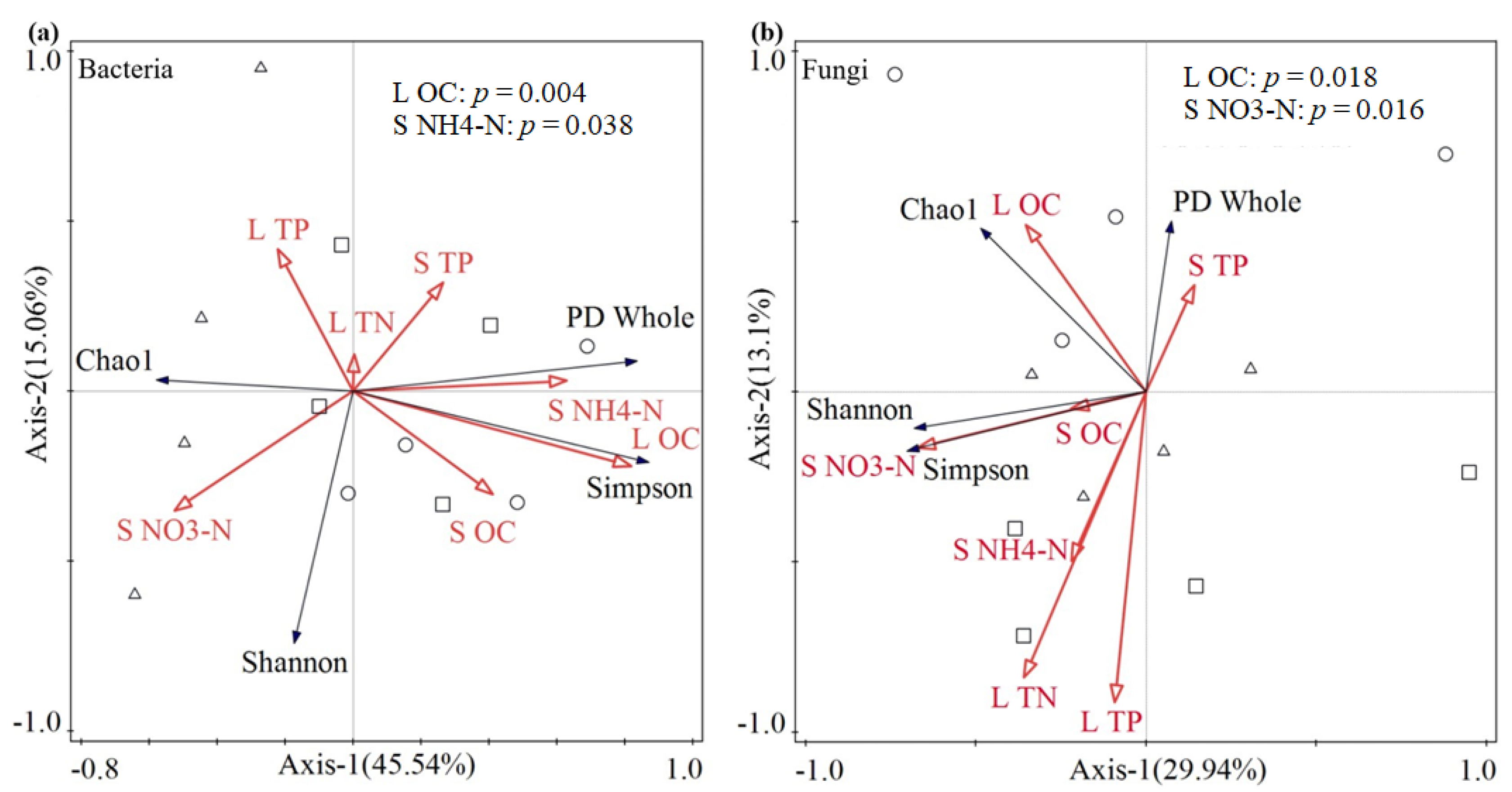

3.5. Redundancy Analysis of Litter Microbial Diversity Indices and Chemical Properties of Litter and Soil

4. Discussion

4.1. Litter Microbial Communities Across Three Forest Stands

4.2. Dynamics of Litter and Soil Nutrients Across Three Forest Stands

4.3. Main Variables Affecting Litter Microbial Community Characteristics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishna, M.P.; Mohan, M. Litter decomposition in forest ecosystems: A review. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 2, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Ye, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Characteristics and hotspots of forest litter decomposition research: A bibliometric analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 2684–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubartová, A.; Ranger, J.; Berthelin, J.; Beguiristain, T. Diversity and decomposing ability of saprophytic fungi from temperate forest litter. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Meng, W.J.; Zhang, Y.M.; Sun, H.; Huang, L. Forest composition and litter quality shape bacterial community dynamics and functional genes during litter decomposition. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 215, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, O.; Bolat, I.; Cakiroglu, K.; Senturk, M. Litter Decomposition and Microbial Biomass in Temperate Forests in Northwestern Turkey. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bani, A.; Pioli, S.; Ventura, M.; Panzacchi, P.; Borruso, L.; Tognetti, R.; Tonon, G.; Brusetti, L. The role of microbial community in the decomposition of leaf litter and deadwood. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 126, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Tian, X.J.; He, X.B.; Song, F.Q.; Ren, L.L.; Jiang, P. Effect of litter quality on its decomposition in broadleaf and coniferous forest. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2008, 44, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: Diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stursová, M.; Zifcáková, L.; Leigh, M.B.; Burgess, R.; Baldrian, P. Cellulose utilization in forest litter and soil: Identification of bacterial and fungal decomposers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 80, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.Y.; Chen, R.R.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.P.; Lin, X.G.; Feng, Y.Z. Important ecophysiological roles of non-dominant Actinobacteria in plant residue decomposition, especially in less fertile soils. Microbiome 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanová, M.; Snajdr, J.; Baldrian, P. Composition of fungal and bacterial communities in forest litter and soil is largely determined by dominant trees. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 84, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Rancon, A.; Fromin, N.; Baldy, V.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Fernandez, C.; Montes, N.; Mirleau, P. Plant litter diversity increases microbial abundance, fungal diversity, and carbon and nitrogen cycling in a Mediterranean shrubland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 111, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.K.; Newman, G.S. Biodiversity at the plant-soil interface: Microbial abundance and community structure respond to litter mixing. Oecologia 2010, 162, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.K.; Wang, M.Y.; Meng, P.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhou, B.Z.; Ge, X.G.; Yu, F.H.; Li, M.H. Native bamboo invasions into subtropical forests alter microbial communities in litter and soil. Forests 2020, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioli, S.; Sarneel, J.; Thomas, H.J.D.; Domene, X.; Andrés, P.; Hefting, M.; Reitz, T.; Laudon, H.; Sandén, T.; Piscová, V.; et al. Linking plant litter microbial diversity to microhabitat conditions, environmental gradients and litter mass loss: Insights from a European study using standard litter bags. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 144, 107778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.R.; Kitajima, K.; Mack, M.C. Temporal dynamics of microbial communities on decomposing leaf litter of 10 plant species in relation to decomposition rate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 49, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Tree species influence on microbial communities in litter and soil: Current knowledge and research needs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 309, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, L.L.; Sayer, E.J. Variability of above-ground litter inputs alters soil physicochemical and biological processes: A meta-analysis of litterfall-manipulation experiments. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 7423–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ouyang, S.N.; Tan, X.P.; Bose, A.K.; Cheng, W.; Tie, L.H. Effects of understory vegetation and climate change on forest litter decomposition: Implications for plant and soil management. Plant Soil 2025, 515, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.M.; Stegen, J.C.; Kim, M.; Dong, K.; Adams, J.M.; Lee, Y.K. Soil pH mediates the balance between stochastic and deterministic assembly of bacteria. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; King, P.T.A.; Benham, M.; Arca, V.; Power, S.A. Ecosystem type and resource quality are more important than global change drivers in regulating early stages of litter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 129, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, J.Y.; Zhang, S.R.; Zhao, W.W. Afforestation promotes ecosystem multifunctionality in a hilly area of the Loess Plateau. Catena 2023, 223, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tao, S.Q.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Qiu, T.; Liu, C.; Sannigrahi, S.; Li, Q.R.; Song, C.H. Divergent socioeconomic-ecological outcomes of China’s conversion of cropland to forest program in the subtropical mountainous area and the semi-arid Loess Plateau. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.H.; Zhen, L.; Yu, X.B.; Bakker, M.; Carsjens, G.J.; Xue, Z.J. Assessing the influences of ecological restoration on perceptions of cultural ecosystem services by residents of agricultural landscapes of western China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, D.X.; Chen, Z.X.; Li, H.; Deng, J.; Qiao, W.J.; Han, X.H.; Yang, G.H.; Feng, Y.Z.; Huang, J.Y. Substrate quality and soil environmental conditions predict litter decomposition and drive soil nutrient dynamics following afforestation on the Loess Plateau of China. Geoderma 2018, 325, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.Z.; Zhou, R.; Tian, T.; Cui, J.Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, G.R.; Xiong, Y.C. Labor force transfer, vegetation restoration and ecosystem service in the Qilian Mountains. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Geng, T.W.; Zhang, H.J. Exploring the linkage between the supply and demand of cultural ecosystem services in Loess Plateau, China: A case study from Shigou Township. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12514–12526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.Y.; Gong, C.; Li, S.J.; Ma, N.; Ge, F.C.; Xu, M.X. Impacts of ecological restoration on public perceptions of cultural ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60182–60194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Song, X.Y.; Ren, Y.Z.; Liu, H.; Qu, H.F.; Dong, X.B. Thinning intensity affects carbon sequestration and release in seasonal freeze-thaw areas. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agriculture Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M.; Mulvaney, C.S. Nitrogen-total. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2: Chemical and Microbial Properties; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; Agronomy Monograph; Agronomy Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; Volume 9, pp. 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorous. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2: Chemical and Microbial Properties; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; Agronomy Monograph; Agronomy Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; Volume 9, pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Liu, G.B.; Li, P.; Xue, S. Ecological stoichiometry of plant-soil-enzyme interactions drives secondary plant succession in the abandoned grasslands of Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2021, 202, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 108, 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.L.; Yu, X.W.; Yang, J.B.; Zhao, X.P.; Bao, Y.Y. High-Throughput Sequencing Reveals the Diversity and Community Structure in Rhizosphere Soils of Three Endangered Plants in Western Ordos, China. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2713–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protocols 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.R.; Shin, J.; Guevarra, R.B.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Seol, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E. Deciphering Diversity Indices for a Better Understanding of Microbial Communities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.S.; Morris, M.M.; Morrow, C.D.; Novak, J.R.; Roberts, M.D.; Frugé, A.D. Associations between changes in fat-free mass, fecal microbe diversity, and mood disturbance in young adults after 10-weeks of resistance training. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jousset, A.; Schmid, B.; Scheu, S.; Eisenhauer, N. Genotypic richness and dissimilarity opposingly affect ecosystem functioning. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Dai, Z.M.; Wang, H.Z.; Dsouza, M.; Liu, X.M.; He, Y.; Wu, J.J.; Rodrigues, J.L.M.; Gilbert, J.A.; Brookes, P.C.; et al. Distinct biogeographic patterns for archaea, bacteria, and fungi along the vegetation gradient at the continental scale in Eastern China. Msystems 2017, 2, e00174-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tláskal, V.; Vorísková, J.; Baldrian, P. Bacterial succession on decomposing leaf litter exhibits a specific occurrence pattern of cellulolytic taxa and potential decomposers of fungal mycelia. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Yang, R.; Peng, X.D.; Hou, C.L.; Ma, J.B.; Guo, J.R. Contributions of plant litter decomposition to soil nutrients in ecological tea gardens. Agriculture 2022, 12, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tian, Q.X.; Liao, C.; Zhao, R.D.; Wang, D.Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.X.; Wang, X.G.; Liu, F. The fate of litter-derived dissolved organic carbon in forest soils: Results from an incubation experiment. Biogeochemistry 2019, 144, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, V.; Traversa, A.; Senesi, N. Forest soil organic carbon dynamics as affected by plant species and their corresponding litters: A fluorescence spectroscopy approach. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.B.; Chen, D.S.; Sun, X.M.; Zhang, Q.; Koide, R.T.; Insam, H.; Zhang, S.G. Impacts of mixed litter on the structure and functional pathway of microbial community in litter decomposition. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 144, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Lauber, C.L.; Ramirez, K.S.; Zaneveld, J.; Bradford, M.A.; Knight, R. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.B.; Bezemer, T.M.; Yang, J.J.; Lü, X.T.; Li, X.Y.; Liang, W.J.; Han, X.G.; Li, Q. Changes in litter quality induced by N deposition alter soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 130, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.L.; Fan, C.H.; Zhang, W.; Li, N.; Liu, H.R.; Chen, M. Heterotrophic nitrification of organic nitrogen in soils: Process, regulation, and ecological significance. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2023, 59, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.L.; Chen, M.; Xu, X.L. Tracing controls of autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification in terrestrial soils. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2022, 110, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Cao, L.X.; Zhang, R.D.; Yan, L.J.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Y.W. Effects of nitrogen addition and litter properties on litter decomposition and enzyme activities of individual fungi. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 80, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Q.; Hui, D.F.; Luo, Y.Q.; Zhou, G.Y. Rates of litter decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems: Global patterns and controlling factors. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest Type | Canopy Density (%) | Altitude (m) | Slope (º) | Main Understory Vegetation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 61 | 1450 | 24 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch |

| 66 | 1489 | 23 | Stipa bungeana Trin | |

| 67 | 1520 | 25 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch | |

| QF | 78 | 1410 | 22 | Bothriochloa ischcemum Linn |

| 81 | 1425 | 23 | Bothriochloa ischcemum Linn | |

| 87 | 1431 | 26 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch | |

| MF | 56 | 1535 | 19 | Artemisia gmelinii Pamp |

| 63 | 1467 | 21 | Artemisia gmelinii Pamp | |

| 50 | 1526 | 23 | Bothriochloa ischcemum Linn |

| Classification | Bacteria | Fungi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | QF | MF | PF | QF | MF | |

| Phylum | 39 | 41 | 34 | 9 | 9 | 7 |

| Class | 45 | 51 | 45 | 25 | 27 | 20 |

| Order | 101 | 118 | 99 | 61 | 52 | 49 |

| Family | 187 | 205 | 186 | 126 | 128 | 119 |

| Genus | 375 | 438 | 374 | 154 | 165 | 141 |

| Chemical Composition | PF | QF | MF |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOC (g/kg) | 347.65 ± 3.58 b | 373.73 ± 5.90 a | 271.03 ± 3.27 c |

| LTN (g/kg) | 7.18 ± 1.14 b | 11.38 ± 1.71 a | 9.20 ± 0.85 b |

| LTP (g/kg) | 15.43 ± 0.58 b | 18.82 ± 0.67 a | 17.78 ± 0.76 a |

| C/N | 49.59 ± 9.56 a | 33.46 ± 5.37 b | 29.63 ± 2.53 b |

| C/P | 22.56 ± 1.07 a | 19.88 ± 0.90 b | 15.26 ± 0.48 c |

| N/P | 0.46 ± 0.06 b | 0.60 ± 0.07 a | 0.52 ± 0.04 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, L.; Min, X.; Yu, S.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Yin, P. Linking Forest Litter Bacterial and Fungal Diversity to Litter–Soil Interface Characteristics. Forests 2026, 17, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010067

Xiao L, Min X, Yu S, Li P, Wang Z, Yin P. Linking Forest Litter Bacterial and Fungal Diversity to Litter–Soil Interface Characteristics. Forests. 2026; 17(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Lie, Xuxu Min, Shu Yu, Peng Li, Zhou Wang, and Penghai Yin. 2026. "Linking Forest Litter Bacterial and Fungal Diversity to Litter–Soil Interface Characteristics" Forests 17, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010067

APA StyleXiao, L., Min, X., Yu, S., Li, P., Wang, Z., & Yin, P. (2026). Linking Forest Litter Bacterial and Fungal Diversity to Litter–Soil Interface Characteristics. Forests, 17(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010067