Habitat Preferences and Ecological Relationships of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes in Central Polish Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Explanation of Concept

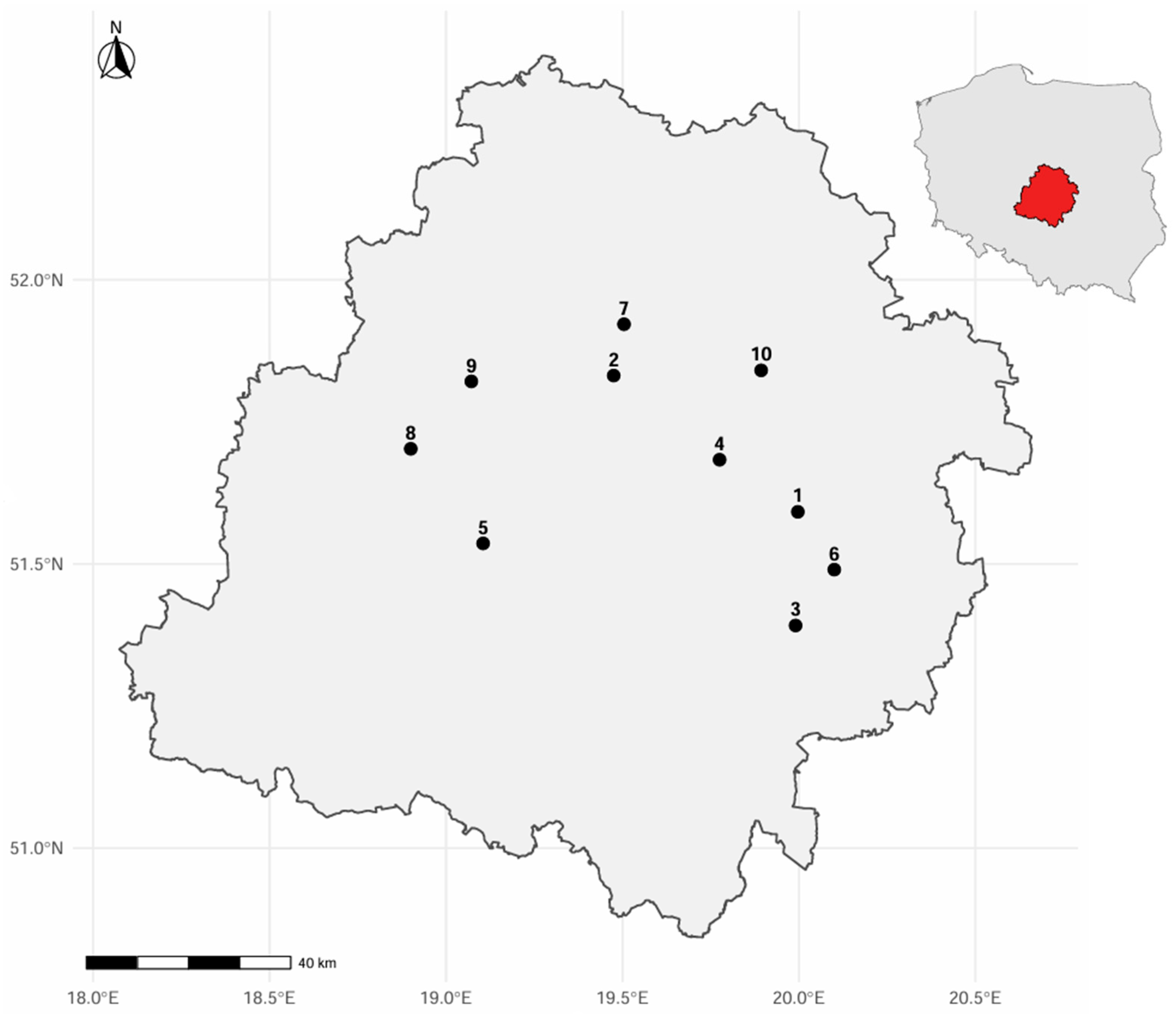

2.2. Sampling Design

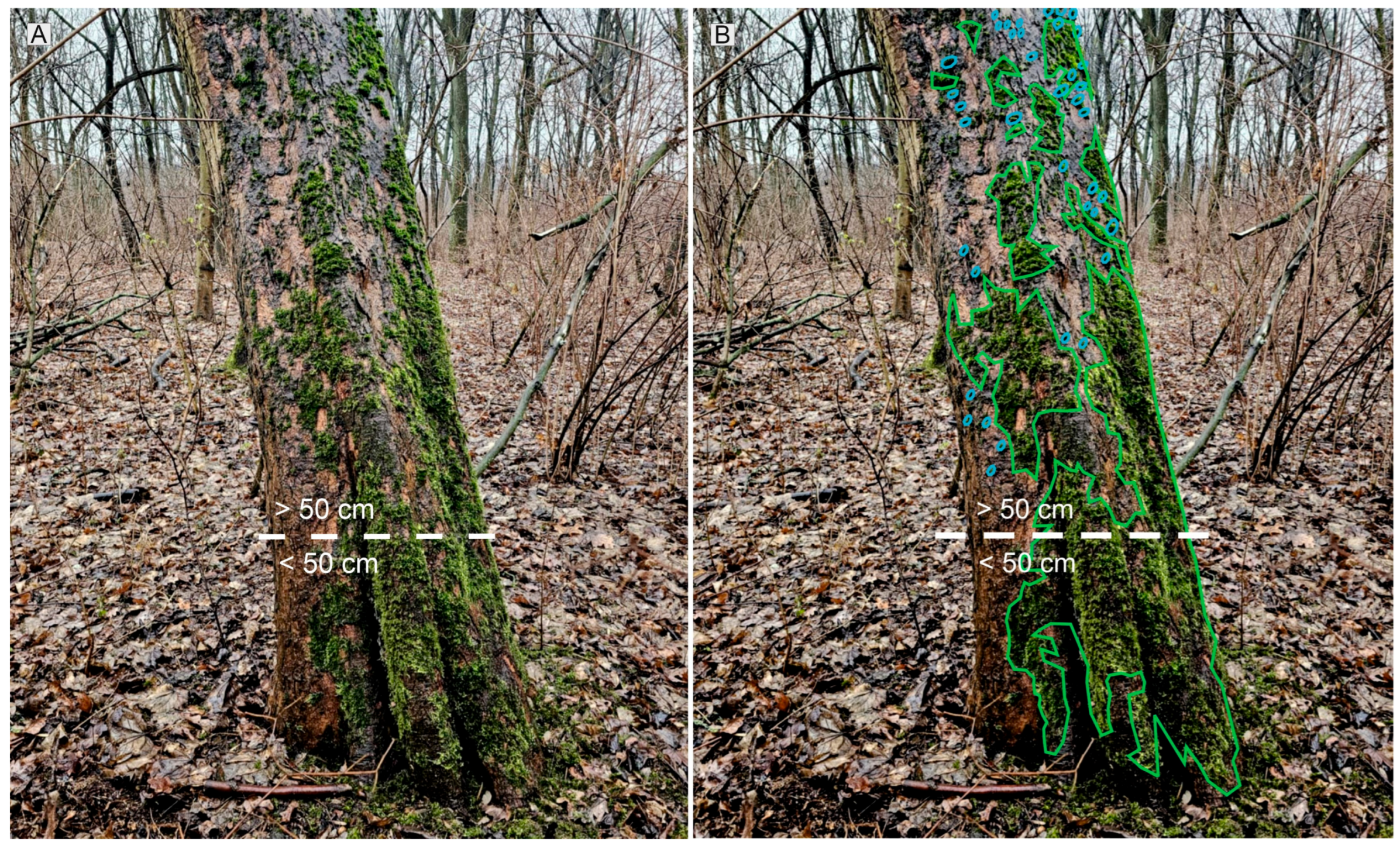

2.3. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

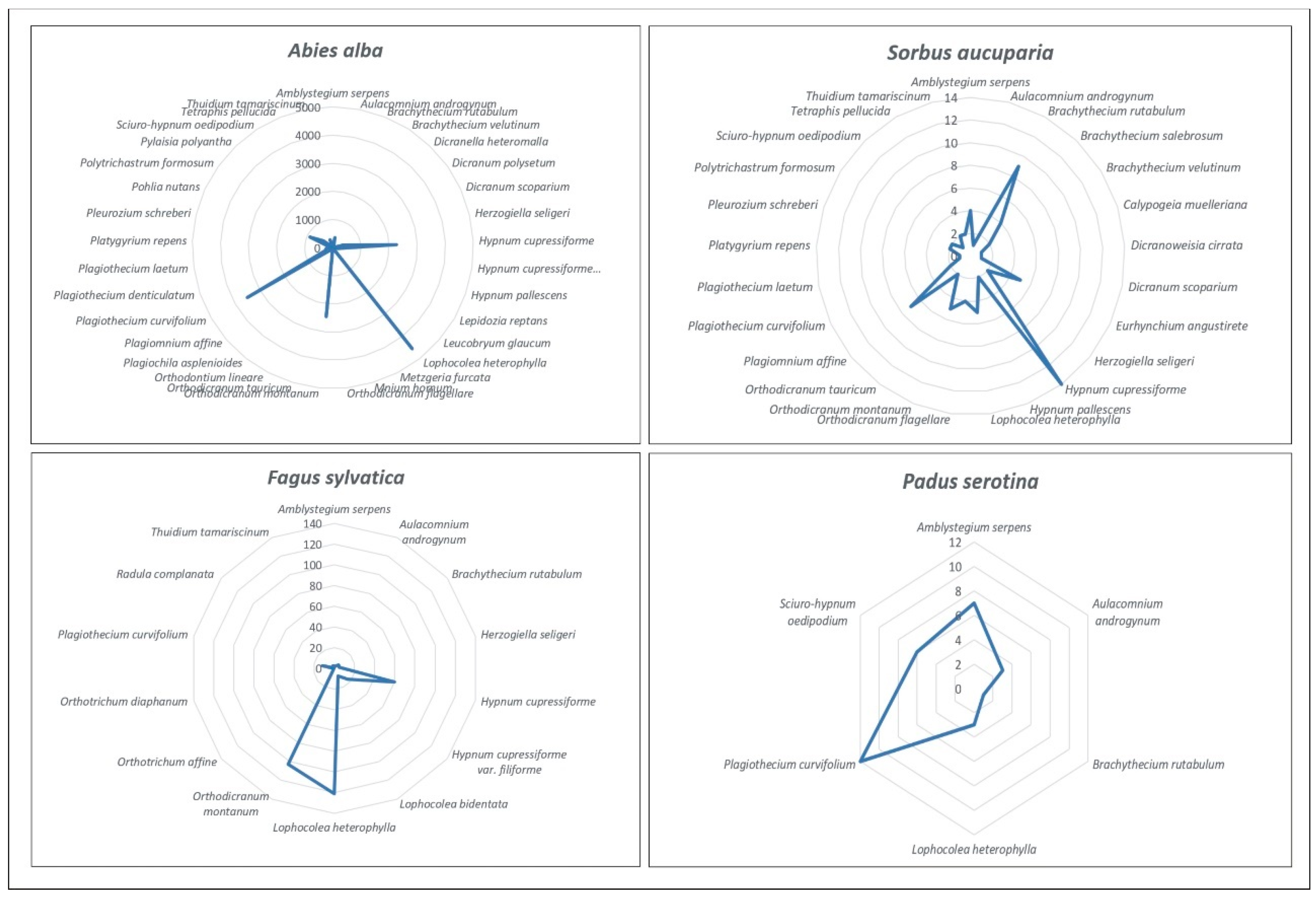

3.1. The Richness of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophyte Flora in the Studied Reserves

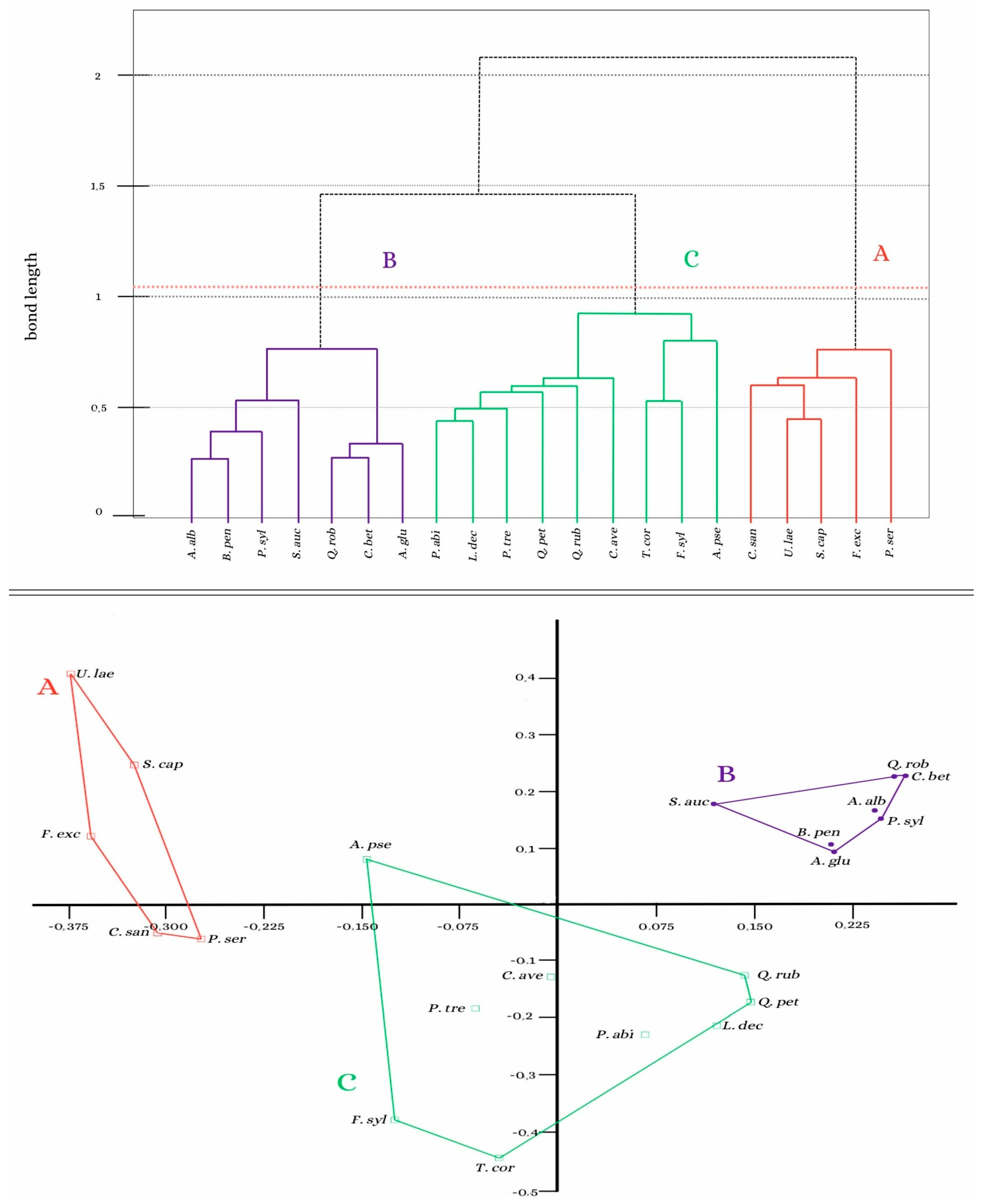

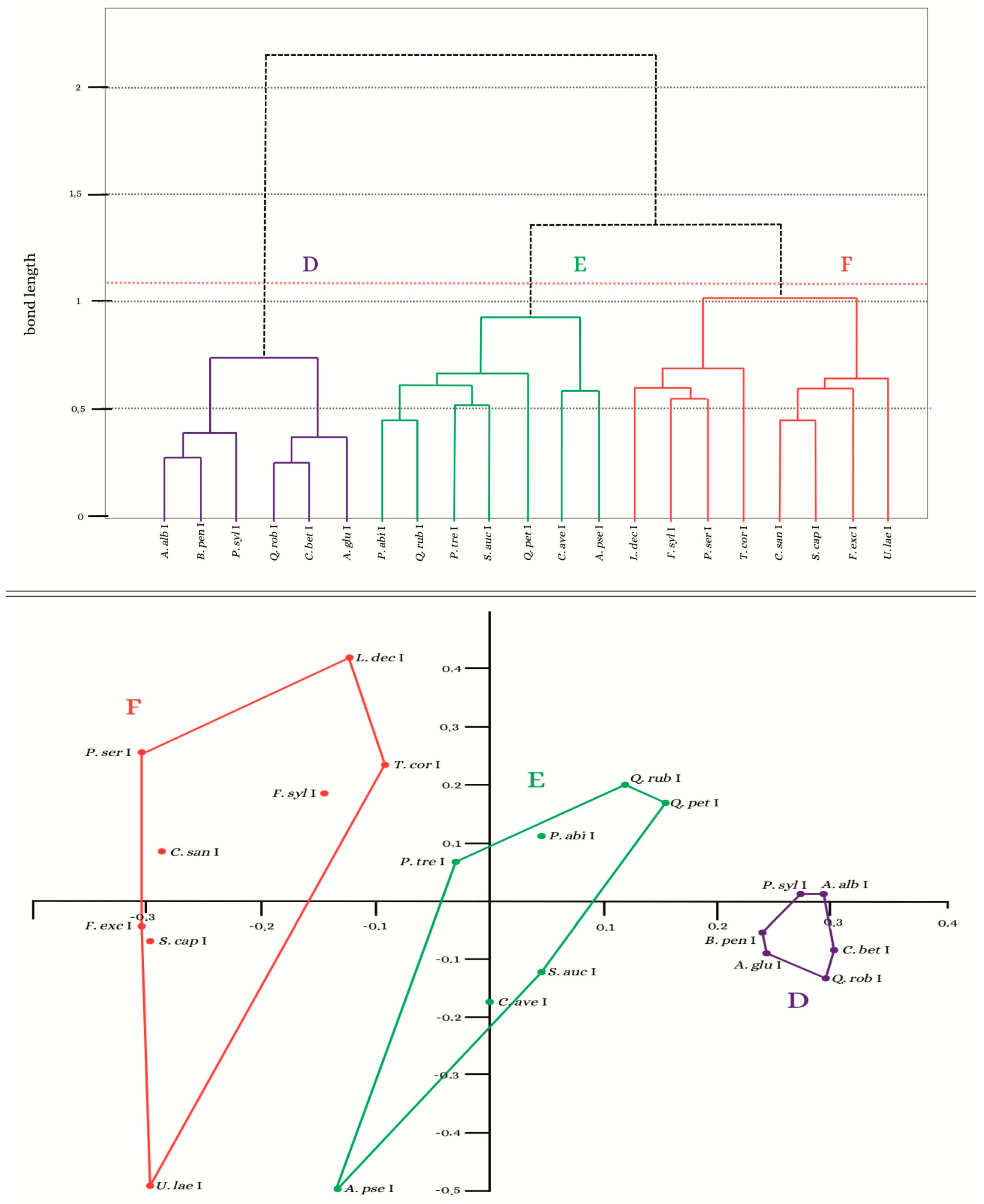

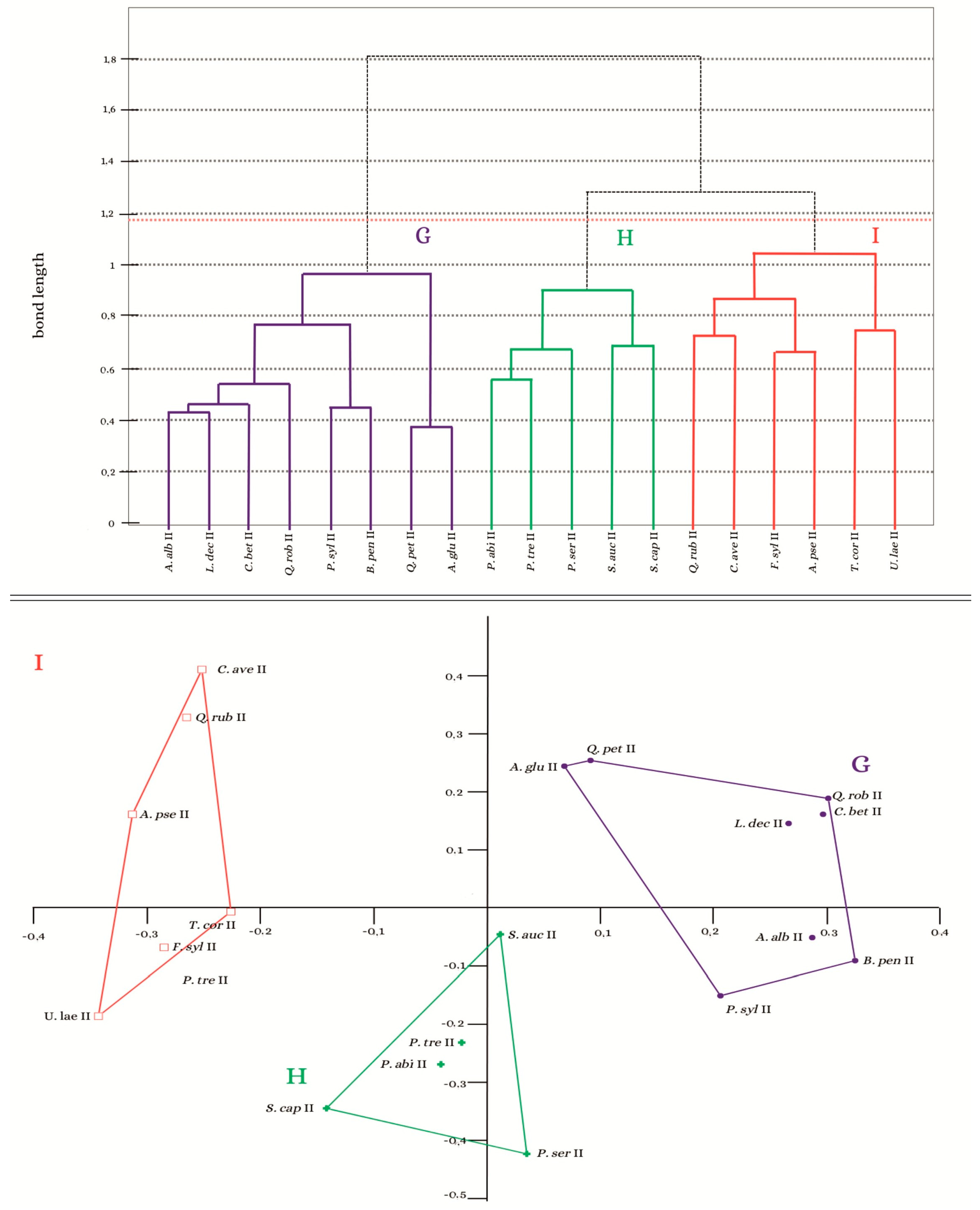

3.2. Analysis of the Similarity of the Bryoflora of Individual Trees

3.3. Assessment of the Bryophyte Flora Growing in Individual Tree Zones

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jakubowska-Gabara, J.; Kucharski, L.; Zielińska, K.; Kołodziejek, J.; Witosławski, P.; Popkiewicz, P. Atlas Rozmieszczenia Roślin Naczyniowych w Polsce Środkowej. Gatunki Chronione, Rzadkie, Ginące i Zagrożenie; Wyd. UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 2011; pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Drymmer, K. Spis roślin zebranych w pow. kutnowskim, w okolicach Żychlina, Kutna, Krośniewic i Orłowa. Pam. Fizjogr. 1885, 5, 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Drymmer, K. Sprawozdanie z wycieczki botanicznej do powiatu tureckiego i sieradzkiego w r. 1889 i 1890. Pam. Fizjogr. 1891, 11, 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mowszowicz, J. Conspectus Florae Lodziensis; Prace Wydz. III ŁTN: Łódź, Poland, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Mowszowicz, J. Conspectus Florae Poloniae Medianae (Plantae Vaculare); Wyd. UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Rezerwat cisowy Jasień. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ. Ser. 1960, 2, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sowa, R. Bardziej interesujące gatunki synantropijne na terenach kolejowych województwa łódzkiego. Fragm. Flor. Geobot. 1966, 12, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Siciński, J.T. Interesujące gatunki segetalne w dorzeczu środkowej Warty (woj. łódzkie). Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Ser. II 1972, 54, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, J.K. Bory i lasy z antropogenicznie wprowadzoną sosną w dorzeczach środkowej Pilicy i Warty. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Bot. 1979, 29, 3–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, J.K. Materiały do flory lasów Wysoczyzny Złoczewskiej w województwie sieradzkim. Acta Univ. Lodz. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Nauki Mat.-Przyr. Ser. II 1979, 27, 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, K.J. Flora naczyniowa zachodniej części rezerwatu Jaksonek w Sulejowskim Parku Krajobrazowym. Przyr. Pol. Środ. 2005, 7, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska-Gabara, J. Notatki florystyczne z doliny Rawki i terenów przyległych. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Bot. 1987, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska-Gabara, J. Materiały do flory naczyniowej lasów okolic Sieradza i Zduńskiej Woli. Acta. Univ. Lodz. Folia Bot. 1990, 7, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski, L. Nowe stanowisko turzycy Davalla Carex davalliana w Polsce Środkowej. Chrońmy Przyr. Ojcz. 1996, 52, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski, L. Szata Roślinna Łąk Polski Środowej i Jej Zmiany w XX Stuleciu; Wyd. UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Witosławski, P. Atlas of Distribution of Vascular Plants in Łódź; Wyd. UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–386. [Google Scholar]

- Staniaszek-Kik, M.; Wolski, G.J. Mszaki—zróżnicowanie, zmiany, zagrożenia. In Szata Roślinna Polski Środkowej; Kurowski, J.K., Ed.; Towarzystwo Ochrony Krajobrazu Wydawnictwo EKO-GRAF: Łódź, Poland, 2009; pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Zespoły leśne województwa łódzkiego ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem mszaków. Cz. I. Zespoły olchowe i łęgowe. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 1966, 35, 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, H. Zespoły borowe województwa łódzkiego ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem mszaków. Cz. III. Bór mieszany. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Nauki Mat.-Przyr. Ser. II 1966, 22, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Zespoły leśne województwa łódzkiego ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem mszaków. Cz. II. Zespoły grądowe. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 1966, 35, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, H. Zespoły leśne województwa łódzkiego ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem mszaków. Cz. IV. Przegląd mszaków w wyróżnionych zespołach leśnych. Fragm. Flor. Geobot. Ser. Pol. 1996, 12, 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Udział i Rola Diagnostyczna Mszaków Oraz Stosunki Florystyczno-Fitosocjologiczne w Przewodnich Zespołach Roślinnych Regionu Łódzkiego i Jego Pobrzeży; Wyd. UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Jakubowska-Gabara, J. Materiłay do brioflory Polski Środkowej. Mchy i wątrobowce rezerwatu leśnego Łaznów. Parki Nar. Rez. Przyr. 2010, 29, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J. Stanowiska inwazyjnych gatunków mchów w mieście Łodzi. Acta Bot. Siles. 2011, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J. Materiały do brioflory Polski Środkowej. Mchy i wątrobowce rezerwatu torfowiskowego Czarny Ług oraz jego otuliny (województwo łódzkie). Parki Nar. Rez. Przyr. 2012, 31, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Kobylińska, A.; Sadowska, B.; Podsędek, A.; Kajszczak, D.; Fol, M. Influence of phytocenosis on the medical potential of moss extracts: The Pleurozium schreberi (Willd. ex Brid.) Mitt. case. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, L.; Fiskesjö, A.; Hallingbäck, T.; Inglög, T.; Petterson, B. Semi-natural deciduous broadleaved woods in southern Sweden—Habitat factors of importance to same bryophyte species. Biodivers. Conserv. 1992, 59, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J. Materiały do brioflory Polski Środkowej. Mchy i wątrobowce rezerwatu leśnego Łaznów (województwo łódzkie) oraz zmiany jego brioflory po 36 latach ochrony. Parki Nar. Rez. Przyr. 2016, 35, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Grabowska, E.; Kucharski, L. Błotniszek wełniasty Helodium blandowii (Bryophyta, Helodiaceae) w Polsce Środkowej. Chrońmy Przyr. Ojcz. 2013, 69, 241–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Fudali, E. Species and ecological diversity of bryophytes occurring on midforest roads in some forest nature reserves in Central Poland. Bot. Steciana 2014, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Fudali, E.; Wolski, G.J. Ecological diversity of bryophytes on tree trunks in protected forests (a case study from Central Poland). Herzogia 2015, 28, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, G.J.; Kruk, A. Determination of plant communities based on bryophytes: The combined use of Kohonen artificial neural network and indicator species analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klama, H. Distribution Patterns of Liverworts (Marchantiopsida) in Natural Forest Communities (Białowieża Primeval Forest, NE Poland); University of Bielsko-Biala: Bielsko-Biala, Poland, 2002; pp. 1–278. [Google Scholar]

- Żarnowiec, J. Wykorzystanie właściwości bioindykacyjnych mchów w fitosocjologii. Zesz. Nauk. ATH—Inżynieria Włókiennicza I Ochr. Sr. 2004, 14, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cieśliński, S.; Czyżewska, K.; Faliński, J.B.; Klama, H.; Mułenko, W.; Żarnowiec, J. Relikty lasu puszczańskiego. In Białowieski Park Narodowy (1921–1996) w Badaniach Geobotanicznych; Faliński, J.B., Ed.; Phytocoenosis 8 N.S. Seminarium Geobotanicum: Warsaw, Poland, 1996; Volume 4, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Klama, H.; Żarnowiec, J.; Jędrzejko, K. Mszaki Naziemne w Strukturze Zbiorowisk Roślinnych Rezerwatów Przyrody Makroregionu Południowego Polski; Politechnika Łódzka Filia w Bielsku-Białej: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 1999; pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- Klama, H. Różnorodność Gatunkowa—Wątrobowce i Glewiki in Różnorodność Biologiczna Polski. Drugi Polski Raport—10 Lat po Rio; Andrzejewski, R., Weigle, A., Eds.; Narodowa Fundacja Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2003; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Stebel, A. The Mosses of the Beskidy Zachodnie as a Paradigm of Biological and Environmental Changes in the Flora of the Polish Western Carpatians. Ph.D. Thesis., Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Katowice-Poznań, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–348. [Google Scholar]

- Fojcik, B. Mchy Wyżyny Krakowsko-Częstochowskiej w Obliczu Antropogenicznych Przemian Szaty Roślinnej; Wyd. Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2011; pp. 1–231. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpoorten, A.; Goffinet, B. Introduction to Bryophytes; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–303. [Google Scholar]

- Mickiewicz, J. Udział mszaków w epifitycznych zespołach buka. Monogr. Bot. 1965, 19, 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mickiewicz, J.; Trocewicz, A. Mszaki epifityczne zespołów leśnych w Białowieskim Parku Narodowym. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 1958, 27, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cieśliński, S.; Czyżewska, K.; Kalma, H.; Żarnowiec, J. Epiphytes and Epiphytism. In Cryptogamous Plants in the Forest Communities of Białowieża National Park. Functional Groups Analysis and General Synthesis (Project CRYPTO 3); Faliński, J.B., Mułenko, W.W., Eds.; Phytocoenosis 8 (N.S.) Archivum Geobotanicum: Warsaw, Poland, 1996; Volume 6, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chlebicki, A.; Żarnowiec, J.; Cieśliński, S.; Klama, H.; Bujakiewicz, A.; Załuski, T. Epixylites, lignicolous fungi and their links with different kinds of wood. In Cryptogamous Plants in the Forest Communities; Faliński, J.B., Mułenko, W., Eds.; Phytocoenosis 8 (N. S.) Archivum Geobotanicum: Warsaw, Poland, 1996; Volume 6, pp. 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, J.W. Mineral nutrition, substratum ecology, and pollution. In Bryophyte Biology; Shaw, A.J., Goffinet, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 248–311. [Google Scholar]

- Gams, H. Vingt aus de Bryocenologie. Rev. Bryol. Lichn. 1953, 22, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, W. Przewodnik do Oznaczania Zbiorowisk Roślinnych Polski; Wyd. Nauk. PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2001; pp. 1–537. [Google Scholar]

- Barkman, J.J. Phytosociology and Ecology of Cryptogamic Epiphytes. Including a Taxonomy Survey and Description of Their Vegetation units in Europe; Van Gorcum & Copmp. N.V.: Asses, The Netherlands, 1958; pp. 1–628. [Google Scholar]

- Fudali, E. Mszaki siedlisk epiksylicznych Puszczy Bukowej—Porównanie rezerwatów i lasów gospodarczych. Przegląd Przyr. 1999, 10, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Herben, T.; Söderström, L. Which habitat parameters are most important for the persistence of a bryophyte species on patchy, temporary substrates? Biodivers. Conserv. 1992, 14, 2061–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.E. Epiphytes and Epiliths. In Bryophyte Ecology; Smith, A.J.E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, K.; Plášek, V.; Rożek, K.; Zubek, S. Effect of tree species identity and related habitat parameters on understorey bryophytes—Interrelationships between bryophyte, soil and tree factors in a 50-year-old experimental forest. Plant Soil 2021, 466, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ódor, P.; Király, I.; Tinya, F.; Bortignon, F.; Nascimbene, J. Patterns and drivers of species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens in managed temperate forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 306, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Hewison, R.L.; Beaton, J.; Douglass, J.R. Identifying substitute host tree species for epiphytes: The relative importance of tree size and species, bark and site characteristics. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, e12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.I.; Hytteborn, H. Bryophytes and decaying wood—A comparison between managed and natural forest. Holarct. Ecol. 1991, 14, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.; Dobson, A.; Klitgaard, K. Bark characteristics affect epiphytic bryophyte cover across tree species. CEC Res. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, N.G. Bryophytes and ecological niche theory. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1990, 104, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glime, J.M. Roles of Bryophytes in Forest Sustainability—Positive or Negative? Sustainability 2024, 16, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski, J.K.; Andrzejewski, H.; Kiedrzyński, M. Ochrona szaty roślinnej i krajobrazu. In Szata Roślinna Polski Środkowej; Kurowski, J.K., Ed.; Towarzystwo Ochrony Krajobrazu, Wydawnictwo EKO-GRAF: Łódź, Poland, 2009; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Faliński, J.B. Kartografia Geobotaniczna; PPWK: Warszawa-Wrocław, Poland, 1990; 1, 1–284, 2, 1–283, 3, 1–353. [Google Scholar]

- Mirek, Z.; Piękoś-Mirkowa, H.; Zając, A.; Zając, M. Flowering Plants and Pteridophytes of Poland—A Checklist; W. Szafer Institute of Botany Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2002; pp. 1–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ochyra, R.; Żarnowiec, J.; Bednarek-Ochyra, H. Census Catalogue of Polish Mosses; Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland, 2003; pp. 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov, M.S.; Milyutina, I.A. On Sciuro-hypnum oedipodium and S. curtum (Brachytheciaceae, Bryophyta). Arctoa 2007, 16, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szweykowski, J. An Annotated Checklist of Polish Liverworts and Hornworts; W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polihs Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, Y.; Morimoto, Y. Identifying indicator species for bryophyte conservation in fragmented forests. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 12, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, G.J.; Sobisz, Z.; Mitka, J.; Kruk, A.; Jukonienė, I.; Popiela, A. Vascular plants and mosses as bioindicators of variability of the coastal pine forest (Empetro nigri-Pinetum). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, G.J.; Celka, Z.; Marciniuk, J.; Marciniuk, P.; Mitka, J.; Nowak, S.; Afranowicz-Cieślak, R.; Kruk, A.; Łysko, A.; Popiela, A. New indicator species for associations within mesotrophic oak-hornbeam forests in Poland. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, H. Rezerwat leśny Lubiaszów. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Nauki Mat.-Przyr. Ser. II 1959, 5, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Rezerwat lipowy Babsk. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Nauki Mat.-Przyr. Ser. II 1961, 10, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Rezerwat leśny Nowa Wieś. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Ser. II 1963, 14, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Materiały do szaty briologicznej Wyżyny Łódzkiej. Zesz. Nauk. UŁ Nauki Mat.-Przyr. Ser. II 1964, 16, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J. Siedliskowe Uwarunkowania Występowania Mszaków w Rezerwatach Przyrody Chroniących Jodłę Pospolitą w Polsce Środkowej. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lodz, Łódź, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, H. Materiały do flory mszaków regionu łódzkiego. Mszaki kompleksów leśnych Dębowca i Żądłowic. Łódzkie Tow. Nauk. Spraw. Z Czynności I Posiedzeń 1965, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Fudali, E. Materiały do brioflory Polski Środkowej. Mchy i wątrobowce rezerwatu leśnego Doliska (województwo łódzkie). Park. Nar. I Rezerwaty Przyr. 2013, 32, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, G.J.; Fudali, E. Materiały do brioflory Polski Środkowej. Mchy i wątrobowce rezerwatu leśnego Jodły Oleśnickie (województwo łódzkie). Park. Nar. I Rezerwaty Przyr. 2013, 32, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Löbel, S.; Snäll, T.; Rydin, H. Epiphytic bryophytes near forest edges and on retention trees: Reduced growth and reproduction especially in old-growth-forest indicator species. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, I.; Nascimbene, J.; Tinya, F.; Ódor, P. Factors influencing epiphytic bryophyte and lichen species richness at different spatial scales in managed temperate forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Plášek, V.; Nobis, M.; Nowak, S. Epiphytic Communities of Open Habitats in the Western Tian-Shan Mts (Middle Asia: Kyrgyzstan). Cryptogam. Bryol. 2016, 37, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbel, S.; Rydin, H. Trade-offs and habitat constraints in the establishment of epiphytic bryophytes. Funct. Ecol. 2010, 24, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzcholska, S.; Łubek, A.; Dyderski, M.K.; Horodecki, P.; Rawlik, M.; Jagodziński, A.M. Light availability and phorophyte identity drive epiphyte species richness and composition in mountain temperate forests. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mežaka, A.; Brumelis, G.; Piterans, A. Tree and stand-scale factors affecting richness and composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens in deciduous woodland key habitats. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 3221–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Igić, R.; Ćuk, M.; Veljić, M.; Radulović, S.; Orlović, S.; Vukov, D. Environmental drivers of ground-floor bryophytes diversity in temperate forests. Oecologia 2023, 202, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, M.; Söderström, L.; Hörnberg, G.; Zackrisson, O.; Hermansson, J. Habitat qualities versus long-term continuity as determinants of biodiversity in boreal old-growth swamp forests. Biol. Conserv. 1997, 81, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.W.; Brown, D.H. Epiphyte differentiation between Quercus petraea and Fraxinus excelsior trees in maritime area of southwest England. Vegetatio 1981, 48, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J. Influence of Chemical and Physical Factors on Quercus and Fraxinus Epiphytes at Loch Sunart, Western Scotland: A Multivariate Analysis. J. Ecol. 1992, 80, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, K.; Rydin, H. Ecophysiological constraints on spore establishment in bryophytes. Funct. Ecol. 2004, 18, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spier, L.; van Dobben, H.; van Dort, K. Is bark pH more important than tree species in determining the composition of nitrophytic or acidophytic lichen floras? Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3607–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steindor, K.; Palowski, B.; Goras, P.; Nadgórska-Socha, A. Assessment of Bark Reaction of Select Tree Species as an Indicator of Acid Gaseous Pollution. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 20, 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Rossell, J.A. Bark in woody plants: Understanding the diversity of a multifunctional structure. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2019, 59, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw, M.; Burton, M. Diversity and distribution of epiphytic bryophytes on Bramley’s Seedling trees in East of England apple orchards. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 4, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, Ö.; Brunet, J.; Caldiz, M. Interacting effects of tree characteristics on the occurrence of rare epiphytes in a Swedish beech forest area. Bryologist 2009, 112, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, S.; Weinrich, T.; Hauck, M.; Leuschner, C. Vertical variation in epiphytic cryptogam species richness and composition in a primeval Fagus sylvatica forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2019, 30, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, A.; Prestø, T. Spruce forest bryophytes in central Norway and their relationship to environmental factors including modern forestry. Ecography 1997, 20, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caners, R.T.; Macdonald, S.E.; Belland, R.J. Responses of boreal epiphytic bryophytes to different levels of partial canopy harvest. Botany 2010, 88, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovářová, M.; Pyszko, P.; Plášek, V. How Does the pH of Tree Bark Change with the Presence of the Epiphytic Bryophytes from the Family Orthotrichaceae in the Interaction with Trunk Inclination? Plants 2021, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinya, F.; Márialigeti, S.; Király, I.; Németh, B.; Ódor, P. The effect of light conditions on herbs, bryophytes and seedlings of temperate mixed forests in Orség, Western Hungary. Plant. Ecol. 2009, 204, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõhmus, P.; Rosenvald, R.; Lõhmus, A. Effectiveness of solitary retention trees for conserving epiphytes: Differential short-term responses of bryophytes and lichens. Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, A.D.; Fischer, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Scattered trees are keystone structures—Implications for conservation. Biol. Cons. 2006, 132, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plášek, V.; Nowak, A.; Nobis, M.; Kusza, G.; Kochanowska, K. Effect of 30 years of road traffic abandonment on epiphytic moss diversity. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 8943–8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevedello, J.A.; Almeida-Gomes, M.; Lindenmayer, D.B. The importance of scattered trees for biodiversity conservation: A global meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüriado, I.; Paal, J.; Liira, J. Epiphytic and epixylic lichen species diversity in Estonian natural forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydin, H. Competition among bryophytes. Adv. Bryol. 1997, 6, 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpoorten, A.; Engels, P.; Sotiaux, A. Trends in diversity and abundance of obligate epiphytic bryophytes in a highly managed landscape. Ecography 2004, 27, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gril, E.; Spicher, F.; Vanderpoorten, A.; Gallet-Moron, E.; Brasseur, B.; Le Roux, V.; Laslier, M.; Decocq, G.; Marrec, R.; Lenoir, J. The affinity of vascular plants and bryophytes to forest microclimate buffering. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.C.F.; Oliver, M.J.; Wood, A.J.; Alpert, P.; Stark, L.R.; Cleavitt, N.L.; Mishler, B.D. Desiccation Tolerance in Bryophytes: A Review. Bryologist 2007, 110, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, J.R.; Bliss, L.C.; Hamilton, C.D. Microclimate control of growth rates and habitats of the boreal forest mosses, Tomenthypnum nitens and Hylocomium splendens. Ecol. Monogr. 1978, 48, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.-W.; Qian, H.; Li, M.; Shi, R.-P.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.-Q.; Wang, J. Effects of Microclimates on Species Richness of Epiphytic and Non-Epiphytic Bryophytes Along a Subtropical Elevational Gradient in China. J. Biogeogr. 2025, 52, e15134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, B.O.; Pócs, T. Distribution and dispersal of bryophytes. Adv. Bryol. 1981, 1, 479–562. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Patterns of dispersal and establishment of bryophytes colonizing natural and experimental treefall mounds in northern hardwood forests. Bryologist 2005, 108, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzcholska, S.; Dyderski, M.K.; Jagodziński, A.M. Potential distribution of an epiphytic bryophyte depends on climate and forest continuity. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2020, 193, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, I.; Ódor, P. The effect of stand structure and tree species composition on epiphytic bryophytes in mixed deciduous–coniferous forests of Western Hungary. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snäll, T.; Riberiro, P.J.; Rydin, H. Spatial occurrence and colonisations in patch-tracking metapopulations: Local conditions versus dispersal. Oikos 2003, 103, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitale, D. Forest and substrate type drive bryophyte distribution in the Alps. J. Bryol. 2017, 39, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Davis, A.L.; Frego, K.A. Propagule sources of forest floor bryophytes: Spatiotemporal compositional patterns. Bryologist 2004, 107, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbel, S.; Rydin, H. Dispersal and life history strategies in epiphyte metacommunities: Alternative solutions to survival in patchy, dynamic landscapes. Oecologia 2009, 161, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-Y.; Liu, W.-Y.; Song, L.; Liu, S.; Shi, X.-M.; Yuan, G.-D. A combination of morphological and photosynthetic functional traits maintains the vertical distribution of bryophytes in a subtropical cloud forest. Am. J. Bot. 2020, 107, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fojcik, B.; Chmura, D. Vertical distribution of epiphytic bryophytes depends on phorophyte type; a case study from windthrows in Kampinoski National Park (Central Poland). Folia Cryptogam. Est. 2020, 57, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Reserve | Area in Hectares [ha] | Phytocenosis in the Area Where Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes were Analyzed |

|---|---|---|

| Kruszewiec | 81.54 | Carpinion betuli |

| Las Łagiewnicki | 69.85 | Carpinion betuli, Quercion robori-petraeae, Potentillo albae-Quercion petraeae |

| Błogie | 69.48 | Alnion glutinosae, Alno-Ulmion, Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion |

| Łaznów | 60.84 | Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion, Piceion abietis |

| Jodły Łaskie | 59.19 | Alnion glutinosae, Alno-Ulmion, Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion, Piceion abietis |

| Jeleń | 47.19 | Alnion glutinosae, Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion |

| Grądy nad Moszczenicą | 42.14 | Alno-Ulmion, Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion |

| Jamno | 22.35 | Carpinion betuli, Dicrano-Pinion |

| Jodły Oleśnickie | 9.88 | Carpinion betuli |

| Doliska | 3.10 | Carpinion betuli |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wolski, G.J.; Cienkowska, A.; Plášek, V. Habitat Preferences and Ecological Relationships of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes in Central Polish Forests. Forests 2026, 17, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010066

Wolski GJ, Cienkowska A, Plášek V. Habitat Preferences and Ecological Relationships of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes in Central Polish Forests. Forests. 2026; 17(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolski, Grzegorz J., Alicja Cienkowska, and Vítězslav Plášek. 2026. "Habitat Preferences and Ecological Relationships of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes in Central Polish Forests" Forests 17, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010066

APA StyleWolski, G. J., Cienkowska, A., & Plášek, V. (2026). Habitat Preferences and Ecological Relationships of Bark-Inhabiting Bryophytes in Central Polish Forests. Forests, 17(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010066