Effects of Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Basic Overview of the Research Object

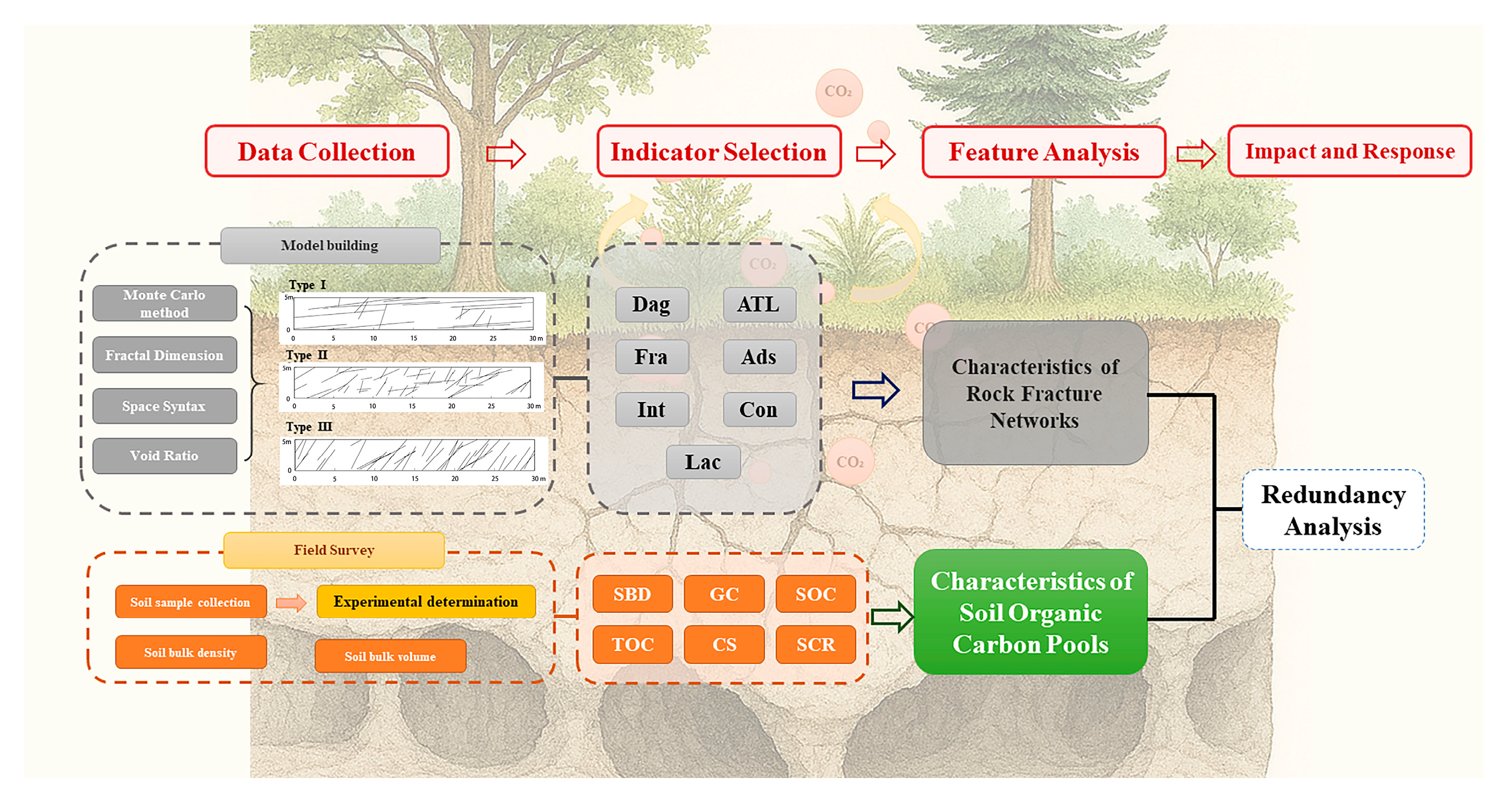

2.2. Research Ideas

2.2.1. Connection with Previous Research and Focus on Scientific Issues

2.2.2. Research Design and Key Techniques

- Habitat Environment Control and Plot Setup

- 2.

- Selection and Explanation of Indicators

- 3.

- Technical Approach and Research Framework

2.3. Characterization and Measurement of Three Types of Rock Fissure Network Rocky Habitats in Karst

2.4. Community Survey

2.5. Soil Sample Collection and Indicator Calculation

2.5.1. Soil Volume Determination, Sample Collection, and Treatment

2.5.2. Determination and Calculation of Soil Carbon Pool Indicators

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Soil Volume, Bulk Density, and Gravel Content in Different Rocky Habitats

3.2. Analysis of Soil Organic Carbon Content (TOC) in Different Rocky Habitats

3.3. Analysis of Soil Organic Carbon Stock in Different Rocky Habitats

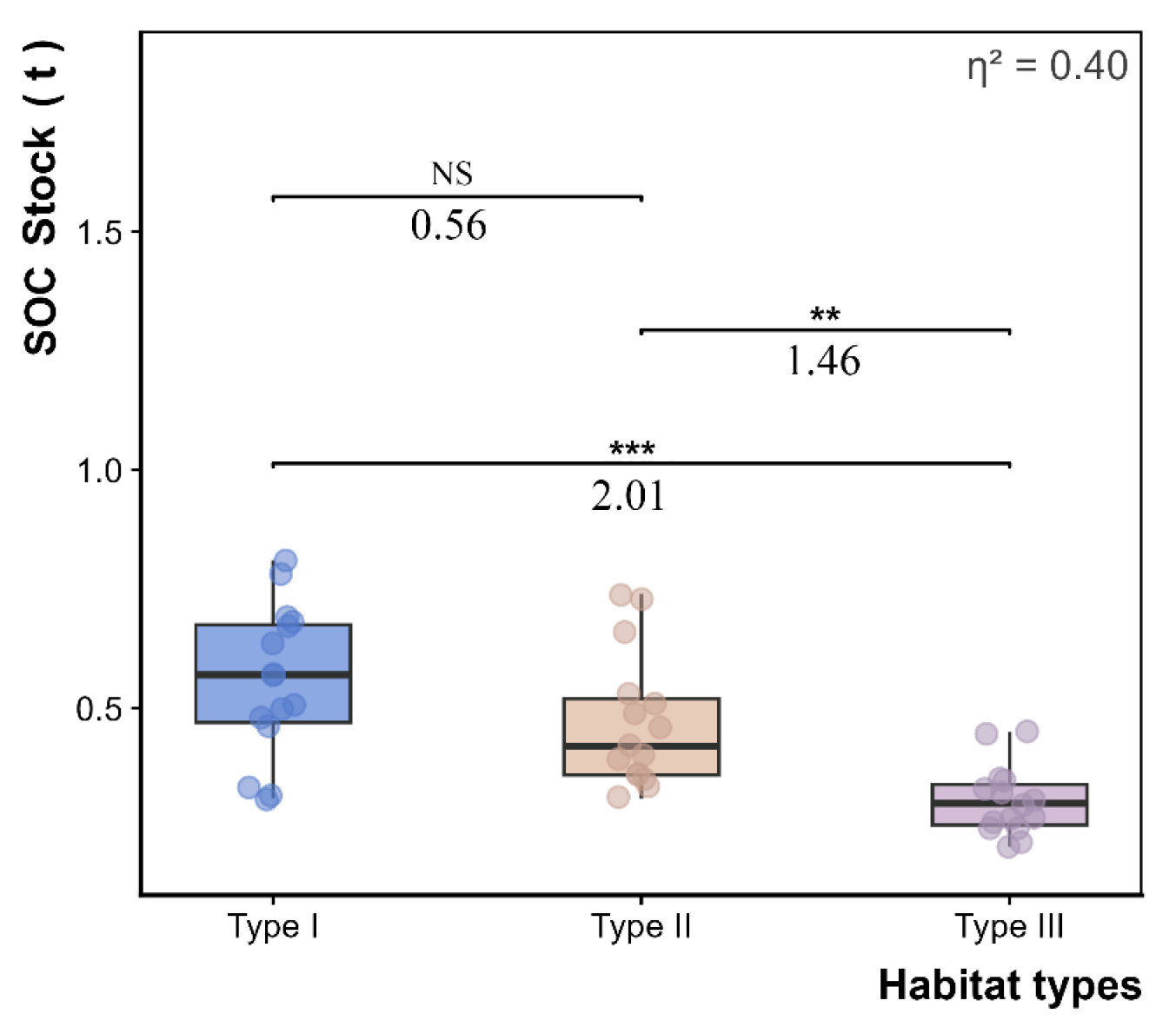

3.4. Analysis of Soil Organic Carbon Density in Different Rocky Habitats

3.5. Analysis of Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rate in Different Rocky Habitats

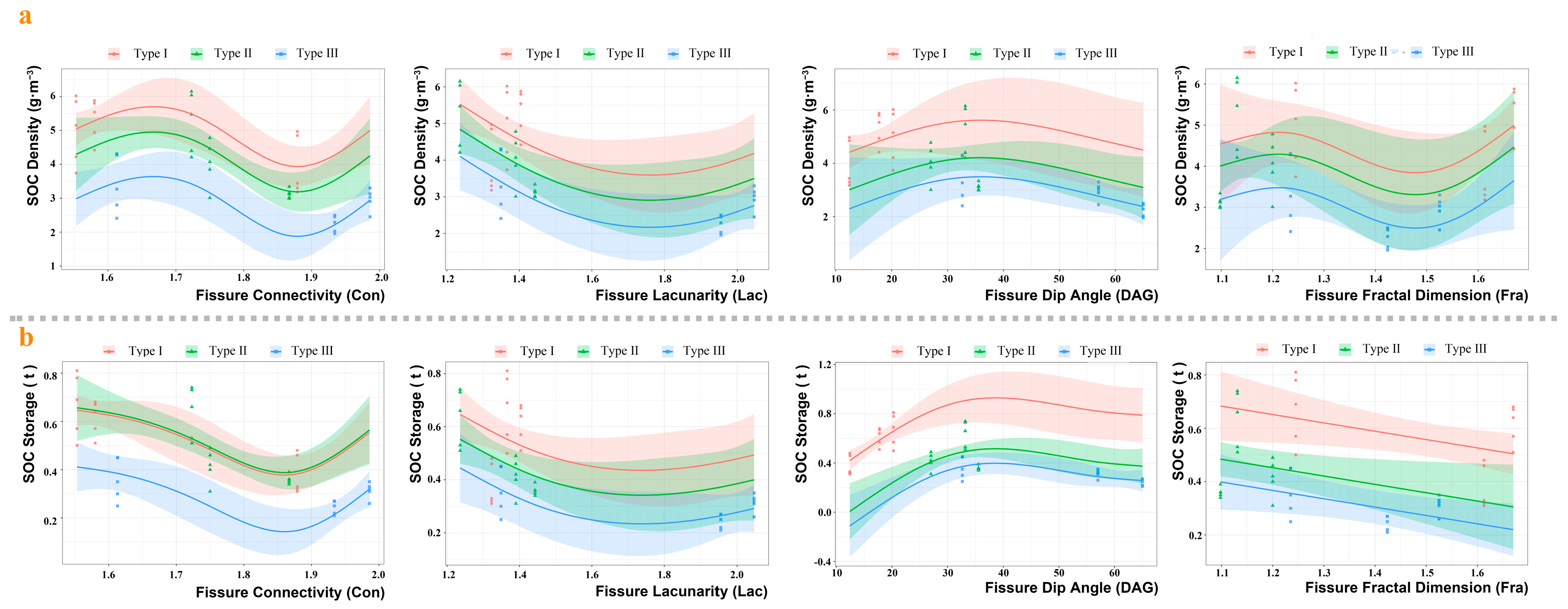

3.6. Relationships Between Fissure Morphology and SOC Pools

3.7. Analysis of the Impact of Rock Fissure Network Structure on Soil Organic Carbon Pools

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact Characteristics of Rock Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats

4.2. Implications of Rock Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pool

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Sixth Assessment Report—IPCC[EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Li, Y.; Xiong, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Luo, D. Distribution and influencing factors of soil organic carbon in a typical karst catchment undergoing natural restoration. Catena 2022, 212, 106078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, X. Estimation of soil organic carbon storage and its fractions in a small karst watershed. Acta Geochim. 2018, 37, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Easter, M.; Paustian, K. Climate change effects on organic carbon storage in agricultural soils of northeastern Spain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 155, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Urbanski, L.; Hobley, E.; Lang, B.; von Lützow, M.; Marin-Spiotta, E.; van Wesemael, B.; Rabot, E.; Ließ, M.; Garcia-Franco, N.; et al. Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils-A review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma 2019, 333, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhang, S.; Gao, H.; Huang, J.; Sun, S.; Song, X.; Fry, E.; Tian, H.; Xia, X. Urban development enhances soil organic carbon storage through increasing urban vegetation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, R.; Huang, C.; Wang, B.; Cao, H.; Koopal, L.K.; Tan, W. Effect of different vegetation cover on the vertical distribution of soil organic and inorganic carbon in the Zhifanggou Watershed on the loess plateau. Catena 2016, 139, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Long, J.; Li, J. Soil organic carbon associated in size-fractions as affected by different land uses in karst region of Guizhou, Southwest China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 6877–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Discrepancies in karst soil organic carbon in southwest china for different land use patterns: A case study of Guizhou Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Lal, R.; Dang, Y.P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stability and its response to no-till: A global synthesis and perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. Soil organic carbon dynamics and driving factors in typical cultivated land on the Karst Plateau. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Shan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, P.; Jiang, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, X. Control of soil organic carbon under karst landforms: A case study of Guizhou Province, in southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, Q. Effects of different land-use types on the activity and community of autotrophic microbes in karst soil. Geoderma 2023, 438, 116635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valjavec, M.B.; Čarni, A.; Žlindra, D.; Zorn, M.; Marinšek, A. Soil organic carbon stock capacity in karst dolines under different land uses. Catena 2022, 218, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y. Spatial heterogeneity of soil organic carbon in a karst region under different land use patterns. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willimas, P.W. The role of the epikarst in karst and cave hydrogeology: A review. Int. J. Speleol. 2008, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, L.; Ladouche, B.; Dörfliger, N. Water storage and transfer in the epikarst of karstic systems during high flow periods. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfar, R.; Mukerji, T. Stochastic geomodeling of karst morphology by dynamic graph dissolution. Math. Geosci. 2024, 56, 1207–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champollion, C.; Deville, S.; Chéry, J.; Doerflinger, E.; Le Moigne, N.; Bayer, R.; Vernant, P.; Mazzilli, N. Estimating epikarst water storage by time-lapse surface-to-depth gravity measurements. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 3825–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, W.; Wu, P. Carbon dioxide partial pressure and its diffusion flux in karst surface aquatic ecosystems: A review. Acta Geochim. 2023, 42, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Fang, F.; Luo, T.; Li, J. Characterization of microbial carbon metabolism in karst soils from citrus orchards and analysis of its environmental drivers. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, L.; Mabit, L.; Lizaga, I.; Navas, A. Lateral mobilization of soil carbon induced by runoff along karstic slopes. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-Q.; Guan, Q.-W.; Huang, Z.-S.; Zhao, J.-H.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zhang, H.; Bao, X.-W.; Wang, L.; Ye, Y.-Q. Morphological characteristics of rock fissure networks and the main factors affecting their soil nutrients and enzyme activities in Guizhou Province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 2587–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, M.; Xiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Lu, S. Soil Nutrient Profiles in Three Types of Rocky Fissure Network Habitats of Typical Karst Formations in China: A Maolan World Heritage Perspective. Forests 2024, 15, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizhou Maolan National Nature Reserve [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.gzmaolan.cn/index.jsp (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Huang, Z.; Yu, L.; Fu, Y.; Yang, R. Carbon Sequestration Characteristics of Ecosystems during Natural Vegetation Restoration in Degraded Karst Forests of Maolan. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2015, 39, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M. Community Structure and Health Assessment of Vegetation Restoration in the Maolan Karst Region. Doctoral Dissertation, Guizhou University, Guizhou, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Yu, L. Evolution of Soil Organic Carbon Pool Characteristics during Natural Vegetation Restoration in Karst Forests. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2013, 50, 306–314. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S. Ecological Studies of Karst Forests III; Guizhou Science and Technology Publishing House: Guiyang, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S. Soil Agrochemical Analysis; China Agricultural Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Soil Physical and Chemical Analysis; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Huang, Y.; Ren, W.; Coyne, M.; Jacinthe, P.-A.; Tao, B.; Hui, D.; Yang, J.; Matocha, C. Responses of soil carbon sequestration to climate-smart agriculture practices: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2591–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, W.; Chen, J.; Alexandrov, G.; Cao, Y. Decipher soil organic carbon dynamics and driving forces across China using machine learning. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 3394–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnmrhar, M.; Bouabdli, A.; Baghdad, B.; Moussadek, R. Unlocking the potential of conservation agriculture for soil carbon sequestration influenced by soil texture and climate: A worldwide systematic review. J. Arid. Agric. 2023, 9, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.A.; VandenBygaart, A.J.; Zentner, R.P.; McConkey, B.G.; Smith, W.; Lemke, R.; Grant, B.; Jefferson, P.G. Quantifying carbon sequestration in a minimum tillage crop rotation study in semiarid southwestern Saskatchewan. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 87, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; He, H.; Cheng, W.; Bai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Factors controlling soil organic carbon stability along a temperate forest altitudinal gradient. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, L.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Han, X.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, O.J. Global pattern of organic carbon pools in forest soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, S.V.; Kurilenko, V.V. Quantitative groundwater estimation of Izhora Plateau, Russian Federation using thermodynamic and kinetic methods for carbonate rock interaction in identified karst terrain. Carbonates Evaporites 2017, 32, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhrushev, B.A.; Amelichev, G.N.; Tokarev, S.V.; Samokhin, G.V. The main problems of karst hydrogeology in the Crimean Peninsula. Water Resour. 2022, 49, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.C.; Pena, J.; Marcus, M.A.; Porras, R.; Pegoraro, E.; Zosso, C.; Ofiti, N.O.E.; Wiesenberg, G.L.B.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Torn, M.S.; et al. Calcium is associated with specific soil organic carbon decomposition products. Soil 2025, 11, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, W.; Nottingham, A.T.; Xiao, D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, J.; Duan, P.; Tang, T.; et al. Lithological controls on soil aggregates and minerals regulate microbial carbon use efficiency and necromass stability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21186–21199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogunovic, I.; Pereira, P.; Coric, R.; Husnjak, S.; Brevik, E.C. Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen stocks in a karst polje located in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiang, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Fu, Y.; Qian, C. Carbon sequestration characteristics of two plantation forest ecosystems with different lithologies of karst. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Peng, Q.; Li, A.; Huang, Z. Soil Quality of Subterranean Habitats in Karst Limestone Formations. J. For. Environ. 2017, 37, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Pan, L. Current Research Status on the Relationship Between Rock Exposure and Soil and Water Loss, and Issues in the Study of Rocky Desertification Factors. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Pan, F.; Yang, S.; Shu, S. Factors controlling accumulation of soil organic carbon along vegetation succession in a typical karst region in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 521, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Dai, Q.; Yan, Y.; He, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Meng, W.; Wang, C. Litter input promoted dissolved organic carbon migration in karst soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, N.W.; Bradford, M.A. Microbial formation of stable soil carbon is more efficient from belowground than aboveground input. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Stark, J.; Waring, B.G. Mineral reactivity determines root effects on soil organic carbon. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, N.W.; Sanderman, J.; Bradford, M.A. Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: Integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Xiao, Q.; Wu, Z.; Martin, K. Ecosystem-driven karst carbon cycle and carbon sink effects. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihevc, A.; Mihevc, R. Morphological characteristics and distribution of dolines in Slovenia, a study of a lidar-based doline map of Slovenia. Acta Carsologica 2021, 50, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hong, I. Evaluation of the usability of UAV LiDAR for analysis of karst (doline) terrain morphology. Sensors 2024, 24, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ads | ATL | Fra | Lac | Dag | Int | Con | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 0.257 | 3.764 | 1.509 | 1.364 | 16.820 | 0.673 | 1.671 |

| Type II | 0.173 | 2.347 | 1.155 | 1.343 | 33.790 | 0.605 | 1.734 |

| Type III | 0.263 | 3.819 | 1.395 | 1.784 | 51.550 | 0.678 | 1.844 |

| Rocky Habitat Type | Plot No. | Elevation (m) | Lithology | Slope (°) | Aspect | Canopy Density | Tree Layer | Shrub Layer | Herb Layer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Species | Mean Height (m) | Mean DBH (cm) | Dominant Species | Mean Height (m) | Dominant Species | Coverage (%) | |||||||

| I | 1 | 634 | Limestone | 26 | WS | 0.41 | Bauhinia purpurea; Boniodendron minus; Clerodendrum mandarinorum | 5.02 | 16.05 | Mallotus philippensis; Tirpitzia sinensis | 1.32 | Nephrolepis cordifolia; Liparis campylostalix | 72 |

| 2 | 684 | Limestone | 30 | 0.44 | 7.17 | 23.79 | 1.16 | 67 | |||||

| 3 | 616 | Limestone | 20 | 0.38 | 6.84 | 27.51 | 1.11 | 74 | |||||

| II | 4 | 597 | Limestone | 25 | WS | 0.63 | Bauhinia purpurea; Staphylea forrestii; Rauvolfia verticillata | 6.32 | 21.96 | Lindera communis; Staphylea forrestii; | 1.25 | Selaginella uncinate; Microstegium vimineum | 68 |

| 5 | 610 | Limestone | 39 | 0.52 | 7.77 | 36.28 | 1.06 | 54 | |||||

| 6 | 656 | Limestone | 32 | 0.62 | 5.26 | 26.30 | 1.21 | 69 | |||||

| III | 7 | 607 | Limestone | 26 | WS | 0.32 | Photinia bodinieri; Eurycorymbus cavaleriei; Pinus massoniana | 5.85 | 27.07 | Lindera communis; Rhus chinensis; zanthoxylum simulans; | 1.43 | Elatostema oblongifolium; Scleria levis Retz; Pilea peploides | 70 |

| 8 | 673 | Limestone | 36 | 0.47 | 8.52 | 36.18 | 1.41 | 64 | |||||

| 9 | 600 | Limestone | 40 | 0.30 | 5.14 | 32.89 | 1.42 | 68 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Xiang, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Huang, X.; Yang, J. Effects of Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats. Forests 2026, 17, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010059

Chen Y, Wang M, Xiang H, Huang Z, Lin Z, Huang X, Yang J. Effects of Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats. Forests. 2026; 17(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yuanduo, Meiquan Wang, Huiwen Xiang, Zongsheng Huang, Zhixin Lin, Xiaohu Huang, and Jiachuan Yang. 2026. "Effects of Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats" Forests 17, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010059

APA StyleChen, Y., Wang, M., Xiang, H., Huang, Z., Lin, Z., Huang, X., & Yang, J. (2026). Effects of Fissure Network Morphology on Soil Organic Carbon Pools in Karst Rocky Habitats. Forests, 17(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010059