Impact of Forest Ecological Compensation Policy on Farmers’ Livelihood: A Case Study of Wuyi Mountain National Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

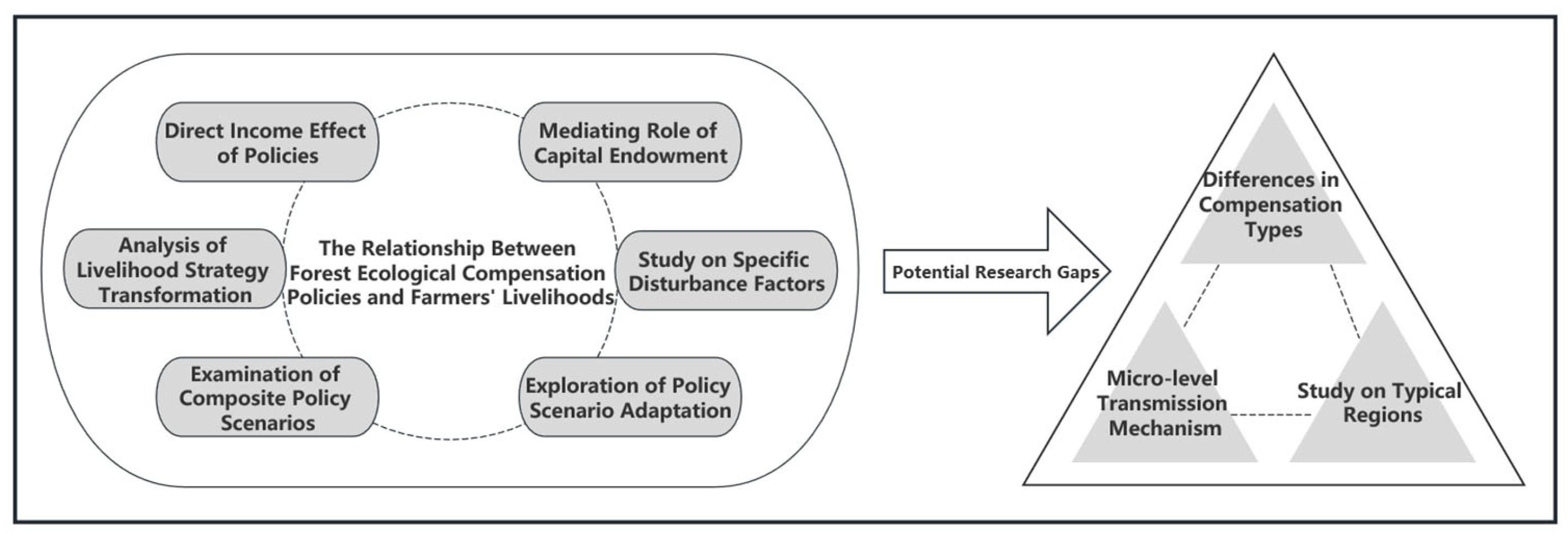

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

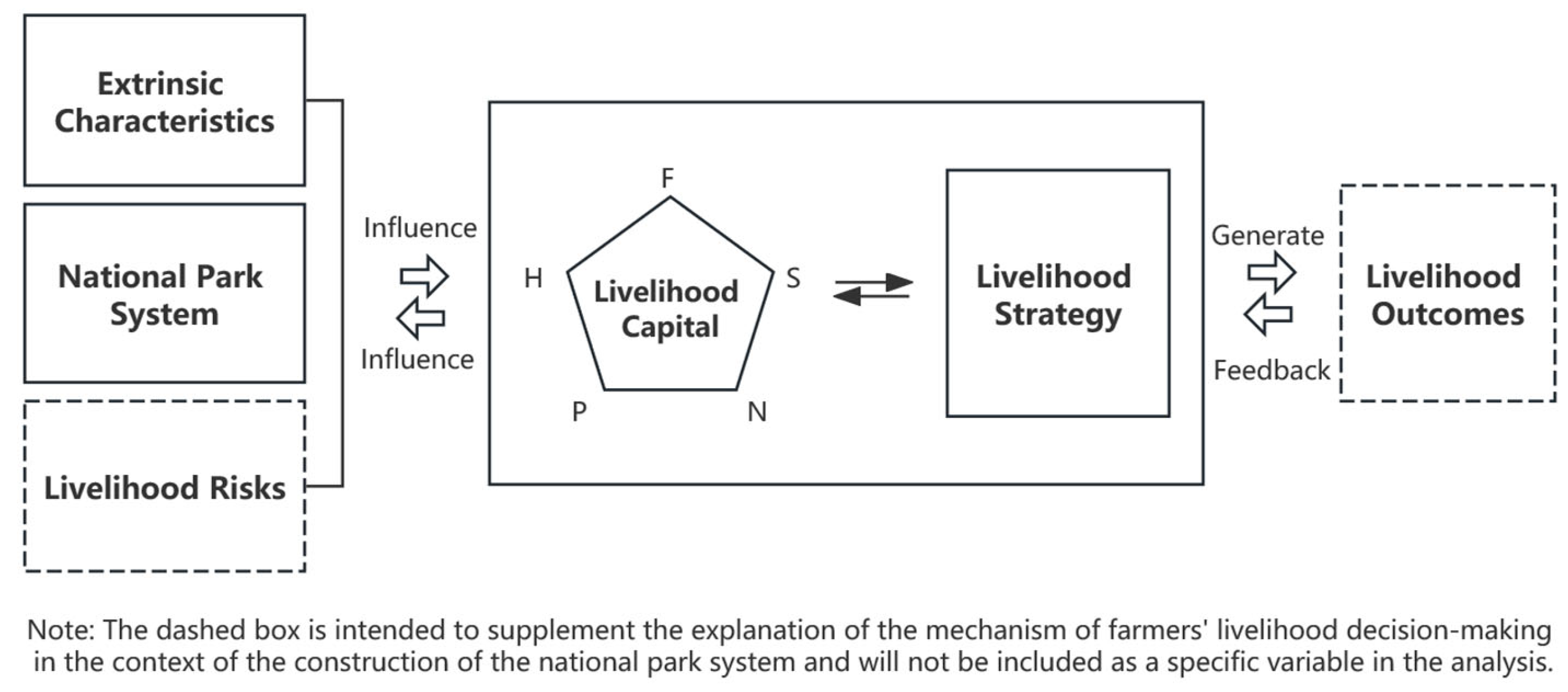

2.1. Analysis of the Impact Mechanism of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital on Their Livelihood Strategy Choices in National Parks

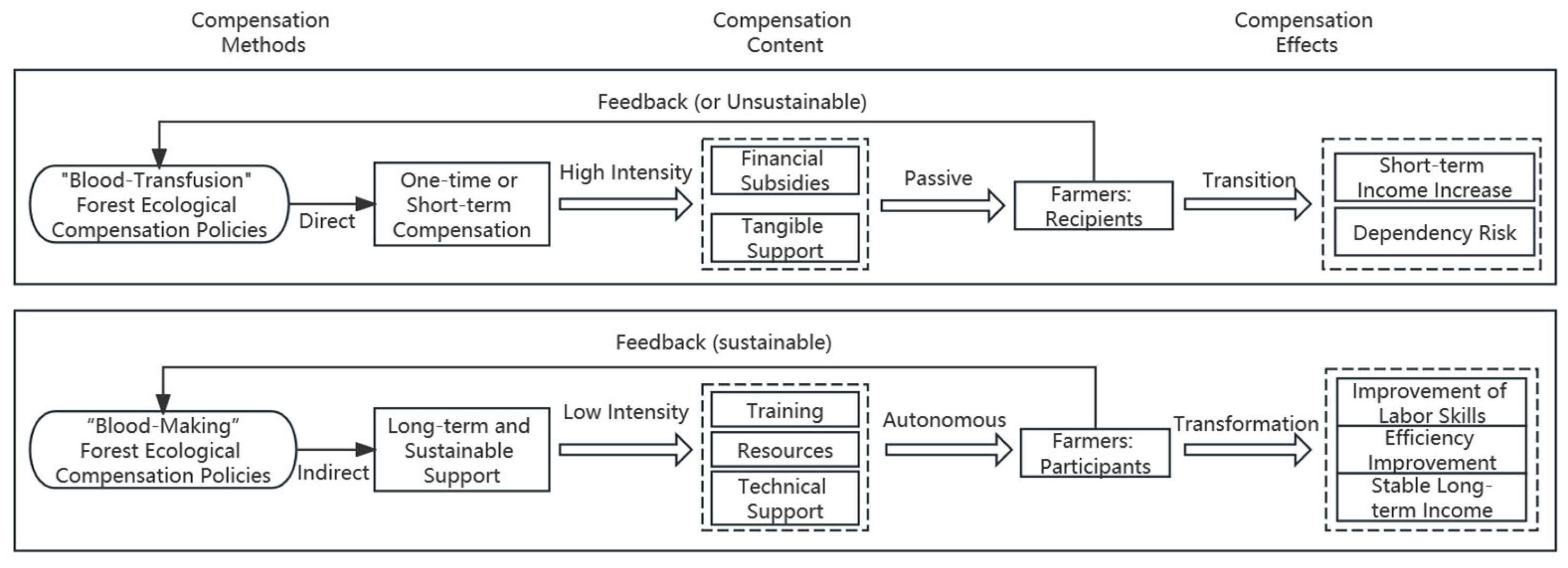

2.2. “Blood-Transfusion” vs. “Blood-Making”: Differences in the Institutional Logic of Forest Ecological Compensation in National Parks

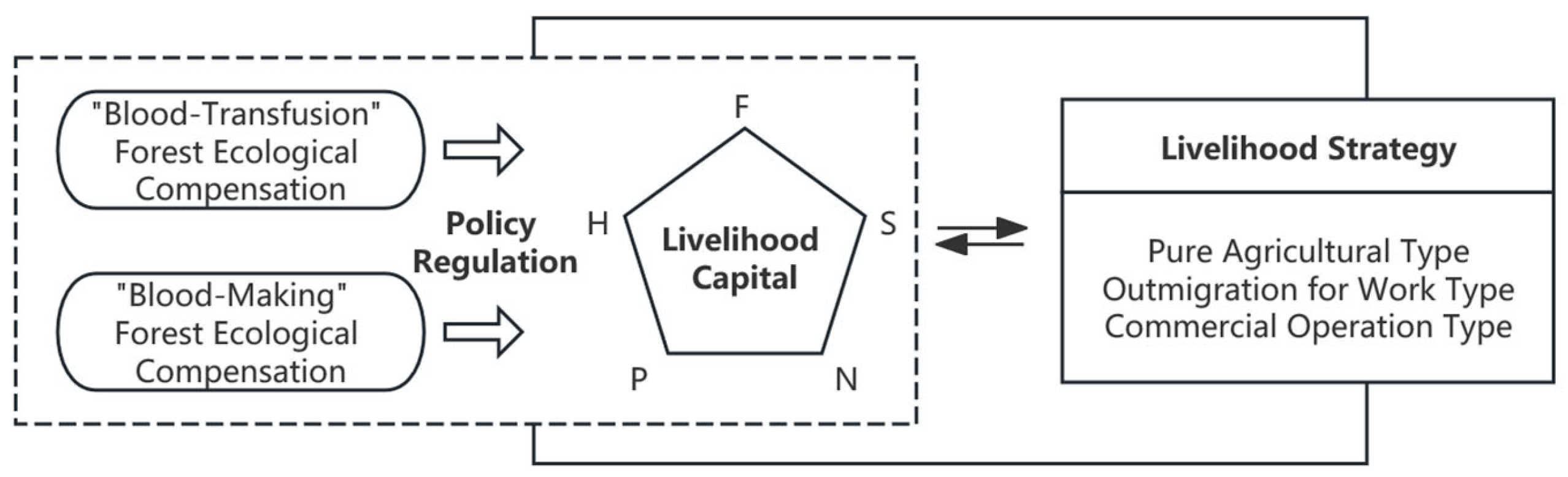

2.3. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Forest Ecological Compensation Policies in National Parks

- (1)

- Dimension of Natural Capital and the Out-Migration for Work Livelihood Strategy. Natural capital serves as the foundation for farmers engaged in traditional agriculture. If its endowment is insufficient, compounded by usage restrictions under the ecological protection constraints of national parks, income from traditional agriculture may fail to cover livelihood expenses, forcing farmers to choose out-migration for work. However, “blood-transfusion” FECPs can directly provide funds to fill the income gap caused by restricted use of natural capital. Even with insufficient natural capital, subsidies can support basic living needs, reducing the necessity to rely on out-migration to supplement income. Consequently, this weakens the association between insufficient natural capital and the choice of out-migration for work. Based on this, H2a is proposed: “Blood-transfusion” FECPs weaken the positive driving effect of insufficient natural capital on the out-migration for work livelihood strategy.

- (2)

- Dimension of Financial Capital and the Out-Migration for Work Livelihood Strategy. Financial capital acts as a livelihood buffer for farmers. If financial capital is scarce, farmers may struggle to cope with short-term fluctuations in local livelihoods and are more inclined to choose out-migration for work to secure stable income. Conversely, if financial capital is ample, farmers have greater buffer space, reducing their willingness to migrate for work. In this context, if farmers receive “blood-transfusion” compensation, those originally lacking financial capital gain additional cash through subsidies, diminishing their need to rely on out-migration to maintain income stability. This weakens the association between financial capital scarcity and the choice of out-migration for work. Accordingly, H2b is proposed: “Blood-transfusion” FECPs weaken the positive driving effect of financial capital scarcity on the out-migration for work livelihood strategy.

- (3)

- The Relationship Between Natural Capital and the Commercial Operation Strategy. In Wuyi Mountain National Park, natural capital is a crucial asset for commercial operations (e.g., tea cultivation for business). Since ecological protection constraints limit traditional income from natural capital, farmers may shift towards commercial activities. “Blood-transfusion” FECPs, by providing cash subsidies, compensate for the income loss from restricted natural capital use. This support reduces the immediate pressure to rely heavily on natural capital for commercial income, thereby potentially weakening the direct, positive driving effect of natural capital on choosing commercial operations. Based on this, H2c is proposed: “Blood-transfusion” FECPs weaken the positive effect of natural capital on the choice of the commercial operation livelihood strategy.

- (4)

- The Relationship Between Financial Capital and the Commercial Operation Strategy. Launching a commercial operation requires initial capital. Farmers within the national park with low savings and limited credit access may find it difficult to afford such investments. “Blood-transfusion” FECPs can directly increase household cash holdings, slightly boosting financial capital and alleviating this constraint to some degree. However, as the primary purpose of these subsidies is to offset livelihood losses, funds are often used for daily consumption. They may only enable low-barrier commercial ventures (e.g., small stalls selling local products) rather than supporting large-scale investments. Therefore, these policies are expected to mildly strengthen the supportive role of financial capital for commercial operations. Accordingly, H2d is proposed: “Blood-transfusion” FECPs strengthen the positive effect of financial capital on the choice of the commercial operation livelihood strategy.

- (1)

- The Relationship Between Social Capital and the Out-Migration for Work Strategy. Out-migration for work often relies on social networks and trust. Farmers participating in “blood-making” FECPs frequently gain opportunities to join organized platforms like cooperatives or industry associations within Wuyi Mountain National Park. These platforms effectively facilitate production collaboration and information sharing among farmers, which can, to some extent, diminish the pull of traditional social networks towards out-migration for work. Therefore, H3a is proposed: “Blood-making” FECPs weaken the positive effect of social capital on the choice of the out-migration for work livelihood strategy.

- (2)

- The Relationship Between Physical Capital and the Out-Migration for Work Strategy. Scarcity of physical capital is a significant factor forcing labor migration. The production facility improvements and industrial support embedded in “blood-making” FECPs can elevate the level of fixed assets available to farmers for forestry production and primary processing. This enhances the attractiveness and feasibility of staying locally to engage in productive activities. Consequently, farmers receiving such support experience substantially reduced pressure to migrate for work due to insufficient physical capital. Accordingly, H3b is proposed: “Blood-making” FECPs weaken the positive driving effect of insufficient physical capital on the choice of the out-migration for work livelihood strategy.

- (3)

- The Relationship Between Social Capital and the Commercial Operation Strategy. Commercial operations require stable supply chains and sales channels. “Blood-making” FECPs, through industrial subsidies and support, guide farmers to join cooperative organizations or establish links with leading enterprises. This lowers the transaction costs and risks for farmers entering the market independently and provides them with operational resources that bring business opportunities and economic returns. Based on this, H3c is proposed: “Blood-making” FECPs strengthen the positive effect of social capital on the choice of the commercial operation livelihood strategy.

- (4)

- The Relationship Between Physical Capital and the Commercial Operation Strategy. The initiation and expansion of commercial operations are highly dependent on specialized fixed assets. Support measures such as subsidies for forestry production equipment and industrial development assistance can, to some degree, offset the operational costs for farmers. Furthermore, these resources can be directly used to enhance product value-added, expand reproduction, or improve service conditions, thereby strengthening the impetus towards choosing a commercial operation strategy. Therefore, H3d is proposed: “Blood-making” FECPs strengthen the positive effect of physical capital on the choice of the commercial operation livelihood strategy.

3. Data Sources, Variable Description, and Model Specification

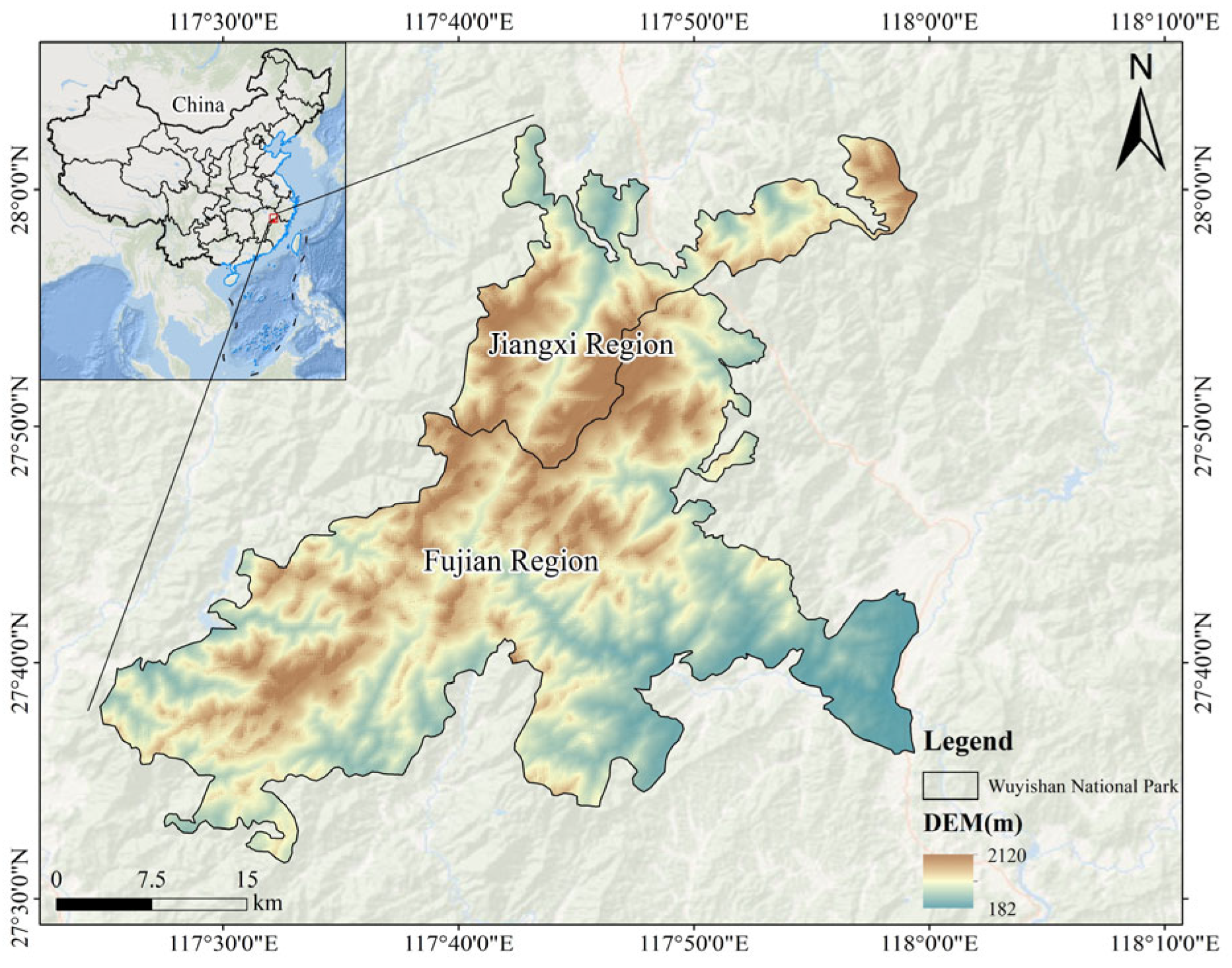

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Description

- (1)

- Dependent Variable: The dependent variable is farmers’ livelihood strategies. Farmers’ livelihood strategies refer to the behavioral strategies adopted by households based on their endowment of livelihood capital. Depending on research purposes, contexts, and methodologies, scholars have adopted different typologies for classifying livelihood strategies. Based on participation in non-agricultural livelihood activities, the presence of non-agricultural income, and the proportion of non-agricultural income, livelihood strategies can be categorized into three types: pure agricultural, agriculture-dominant with non-agricultural sidelines, and non-agriculture-dominant with agricultural sidelines. Based on the composition of total household income, strategies can be classified into traditional livelihood specialization, non-agricultural specialization, diversification, and subsidy dependence. According to participation in livelihood activities, farmers’ livelihood strategies can be divided into four categories: crop and forestry cultivation, livestock breeding, non-agricultural business operations, and out-migration for work. Drawing on existing research and considering the specific context of Wuyi Mountain National Park, this paper selects the pure agricultural type, out-migration for work type, and commercial operation type to represent livelihood strategies.The pure agricultural type refers to households whose livelihood activities center on traditional crop and forestry production, with their main household income derived from agricultural activities directly related to forest resources, such as tea cultivation, moso bamboo management, and seedling cultivation. The out-migration for work type refers to households whose livelihood activities focus on non-agricultural employment. Their main household income comes from wage work performed by household members outside their registered residence or in local non-agricultural sectors. This includes employment in distant factories, construction work, domestic services, and forestry-related non-agricultural labor. The commercial operation type refers to households engaged in self-employed business activities. Their main household income stems from business operations leveraging the ecological resources of Wuyi Mountain National Park or local specialty industries, including ecotourism services, deep processing of forest products, and retail sales.

- (2)

- Explanatory Variables: Livelihood capital serves as the explanatory variable in this study, encompassing five dimensions: human, natural, social, physical, and financial capital. First, human capital refers to the intangible resources possessed by households, such as knowledge, skills, and health status, that support production and livelihood. This study uses education level and physical health status to measure human capital. Second, natural capital denotes the tangible natural resources directly usable by households and related to the ecological environment. This study employs tea garden area and moso bamboo forest area to measure natural capital. Third, social capital refers to the ability of households to obtain resource support through social networks, trust relationships, and reputation. It serves as a crucial social foundation for farmers to access information, seek opportunities, and expand livelihood options. This study uses social networks and social trust to measure social capital. Fourth, physical capital comprises the material infrastructure and production tools used by households for production and daily life. This study selects house area and the value of household physical assets to measure physical capital. Fifth, financial capital refers to the financial resources at the disposal of and accessible to households, including cash, savings, and credit. This study uses access to loans and annual household income to measure financial capital.

- (3)

- Moderating Variable: Forest ecological compensation policies (FECPs) serve as the moderating variable in this study. Classifying FECPs into “blood-transfusion” and “blood-making” types for discussion holds greater practical significance and facilitates a more in-depth analysis of the policies. This paper defines the variables based on the specific policy items outlined in the Implementation Measures for Establishing an Ecological Compensation Mechanism in Wuyi Mountain National Park. Accordingly, “blood-transfusion” FECPs specifically include compensation for ecological public welfare forests, subsidies for logging bans and forest management, compensation for forest right owners, and resettlement compensation for ecological migrants. “Blood-making” FECPs primarily refer to subsidies for forestry industry development, subsidies for forestry production equipment, subsidies for the purchase of physical seeds (e.g., seedlings), and similar measures. To obtain specific information on farmers’ participation in FECPs, this study used the survey questions: “How many types of ecological compensation policy subsidies have you received? What are these subsidies? And how are the subsidies specifically distributed?”.

- (4)

- Control Variables: To control for the potential influence of basic household characteristics on livelihood strategy choices, this study selects the following variables as control variables: First, gender. This refers to the gender of the household head, reflecting gender differences in the primary decision-maker of the household. In rural contexts, gender is often associated with the division of labor, risk preferences, and access to resources. For example, men may be more likely to engage in out-migration for work or commercial operations, while women may focus more on agricultural production. It is necessary to control for its potential effect on livelihood strategy choice. Second, age. This refers to the actual age of the household head, reflecting labor capacity, willingness to adopt new things, and risk tolerance. Older farmers often experience declining labor capacity and have more fixed livelihood pathways, making them more inclined to maintain traditional pure agriculture or rely on subsidies. Younger farmers are more likely to venture into out-migration for work or commercial operations. The influence of this variable needs to be controlled. Third, the number of household laborers. This refers to the total number of family members with the capacity to work who can participate in production and business activities, reflecting the total labor supply of the household. The number of laborers directly determines the scale of human resources a household can allocate to agricultural cultivation, commercial operations, or out-migration for work. For instance, households with sufficient labor are more capable of engaging in commercial operations, while those with labor shortages may rely more on out-migration or subsidies. This constitutes a key foundational variable affecting livelihood strategy choice. The names, definitions, measurements, and descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 1.

3.3. Model Specification

- (1)

- Multinomial Probit Model. Given that the livelihood strategies of farmers in Wuyi Mountain National Park exhibit the characteristic of multiple category choices, this paper employs the multinomial probit (mprobit) model to conduct an empirical analysis of farmers’ livelihood strategy selection behavior, including three types: “pure agricultural livelihood strategy”, “outmigration for work livelihood strategy”, and “commercial operation livelihood strategy”. Compared with the multinomial logit model, the multinomial probit model does not rely on the “Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives” assumption. It can more flexibly depict the correlation structure between various livelihood strategies, thus being more suitable for the research context of this paper. The general form of the model is as follows (Model 1):Among them, is the livelihood capital vector of farmer k, is the coefficient vector corresponding to the j-th strategy, and is the cumulative distribution function of the multivariate normal distribution.

- (2)

- Moderating Effect Model. To examine the differentiated moderating effects of the two types of forest ecological compensation policies—“blood-transfusion” and “blood-making”—this study adopts a grouped regression comparison strategy. Specifically, based on the baseline mprobit model, the overall sample is first divided into a “blood-transfusion” policy sample group and a “blood-making” policy sample group according to policy type. Subsequently, within each policy type, the sample is further split into two subsamples based on whether farmers actually participated in the policy: a “participant group” and a “non-participant group”.

4. Result

4.1. Analysis of Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices in National Parks

4.2. Impact of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital on Their Livelihood Strategy Choices in National Parks

4.3. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Forest Ecological Compensation on the Impact of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital on Their Livelihood Strategies

- (1)

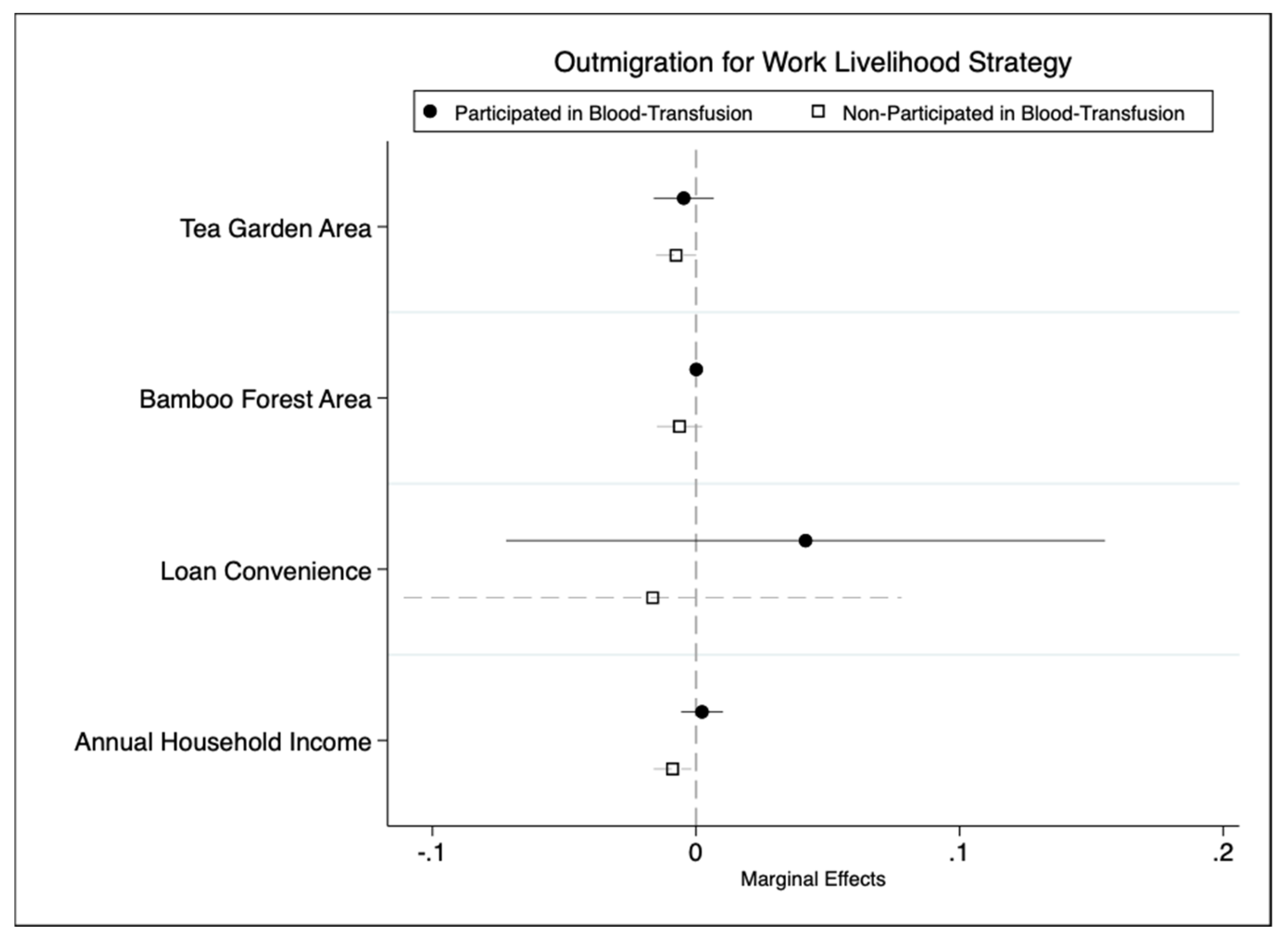

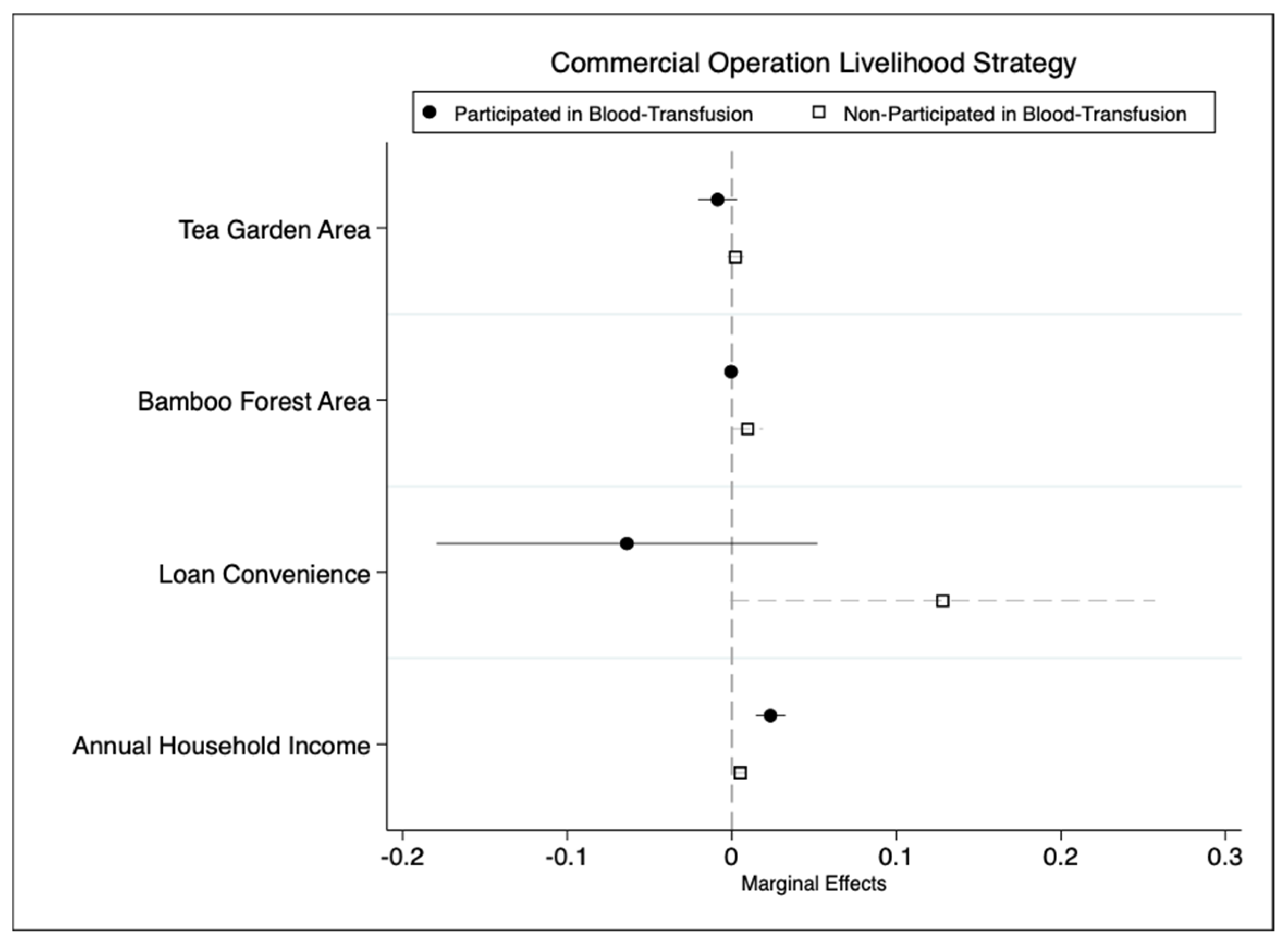

- Analysis of the Moderating Effect of “Blood-Transfusion” Forest Ecological Compensation Policies on the Relationship between Farmers’ Livelihood Capital and Their Livelihood Strategies (Table 4).First, the moderating effect of “blood-transfusion” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between natural capital and the out-migration for work livelihood strategy (Figure 6). Among farmers who did not participate in the “blood-transfusion” compensation policy, each additional mu of tea garden area reduced the probability of choosing the out-migration strategy by an average of 0.8 percentage points, and the effect was significant at the 5% level. This confirms the “locking-in effect” of natural capital: the larger the tea garden area, the less willing farmers are to migrate for work. However, in the group that participated in the “blood-transfusion” policy, the effect of tea garden area became statistically insignificant (marginal effect = –0.004, p > 0.1), and its magnitude was halved. This change indicates that the direct income support provided by “blood-transfusion” compensation effectively alleviates the pressure that keeps farmers from migrating due to tea-garden maintenance needs, partially offsetting the “locking-in effect” of natural capital. Consequently, it weakens the constraint that natural capital endowment imposes on labor outflow, supporting Hypothesis H2a.Second, the moderating effect of “blood-transfusion” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between financial capital and the out-migration for work livelihood strategy (Figure 6). In the group that did not participate in any forest ecological compensation policy, each 10,000-yuan increase in annual household income reduced the probability of choosing out-migration by an average of 0.9 percentage points (significant at the 5% level). This suggests that in the absence of “blood-transfusion” compensation, the scarcer a household’s own financial capital, the stronger the motivation to migrate for work in search of stable cash flow. In the policy-participation group, however, this relationship became statistically insignificant (marginal effect = 0.002, p > 0.1). This shift confirms that “blood-transfusion” compensation, as an exogenous and stable cash inflow, provides a direct livelihood buffer for low-income households, reducing their economic vulnerability to local income fluctuations or shortfalls that would otherwise force them to migrate. Thus, it weakens the driving effect of household financial-capital scarcity on out-migration decisions, validating Hypothesis H2b.Third, the moderating effect of “blood-transfusion” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between natural capital and the commercial operation livelihood strategy (Figure 7). In the group that did not participate in “blood-transfusion” compensation, each additional mu of moso-bamboo forest area raised the probability of choosing commercial operation by an average of 0.9 percentage points, significant at the 5% level. This indicates that, in the absence of such policies, greater bamboo-forest resources constitute both a resource base and a motive for farmers to shift toward commercial operations, compensating for traditional income losses due to conservation restrictions. However, in the policy-participation group, this driving effect disappeared (marginal effect = –0.001, insignificant). This suggests that “blood-transfusion” compensation directly fills the income gap caused by restricted resource use, so that farmers no longer need to rely on developing their own bamboo-forest resources for commercial conversion to maintain income. Thereby, it weakens the positive driving force of natural-capital stock on the commercial-operation strategy, supporting Hypothesis H2c.Fourth, the moderating effect of “blood-transfusion” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between financial capital and the commercial operation livelihood strategy (Figure 7). Regarding annual household income, the marginal effect in the non-participation group was 0.005 (significant at the 5% level), indicating that higher household income enhances the tendency toward commercial operation. In the participation group, the marginal effect increased to 0.024 (significant at the 1% level), with both significance and magnitude rising. This shows that the cash injection from “blood-transfusion” compensation supplements farmers’ financial-capital stock and strengthens the supportive capacity of household income for commercial operations. Regarding access to loans, loan convenience had a positive effect in the non-participation group (marginal effect = 0.128, significant at the 10% level), whereas in the participation group the effect was insignificant and even reversed in direction (–0.064). This is likely because direct cash compensation partially substitutes for the need for external financing, especially for small-scale operations. Overall, the “blood-transfusion” policy mainly strengthens the support of financial capital for commercial operation by boosting household cash flow rather than improving credit channels, validating Hypothesis H2d.

- (2)

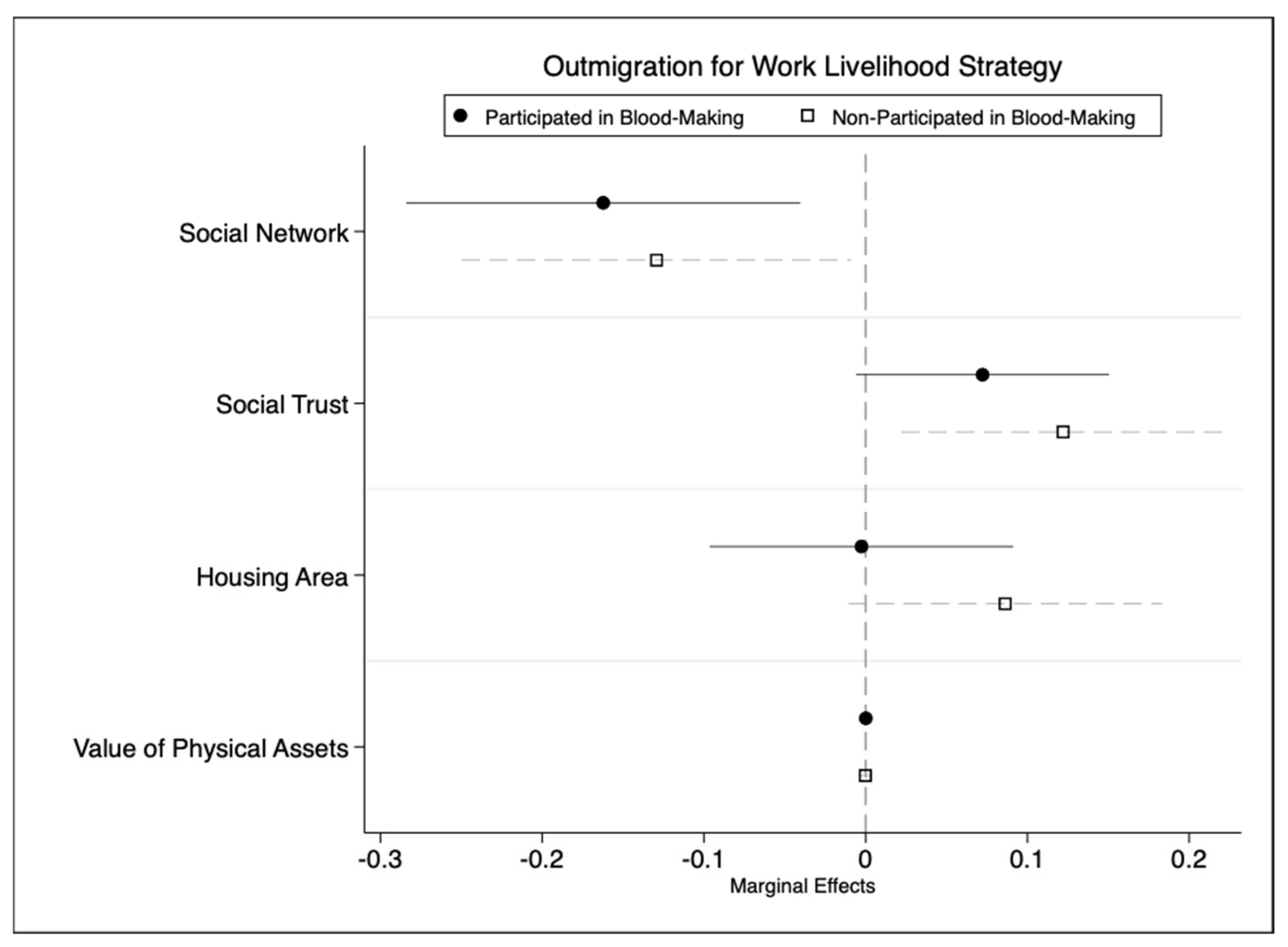

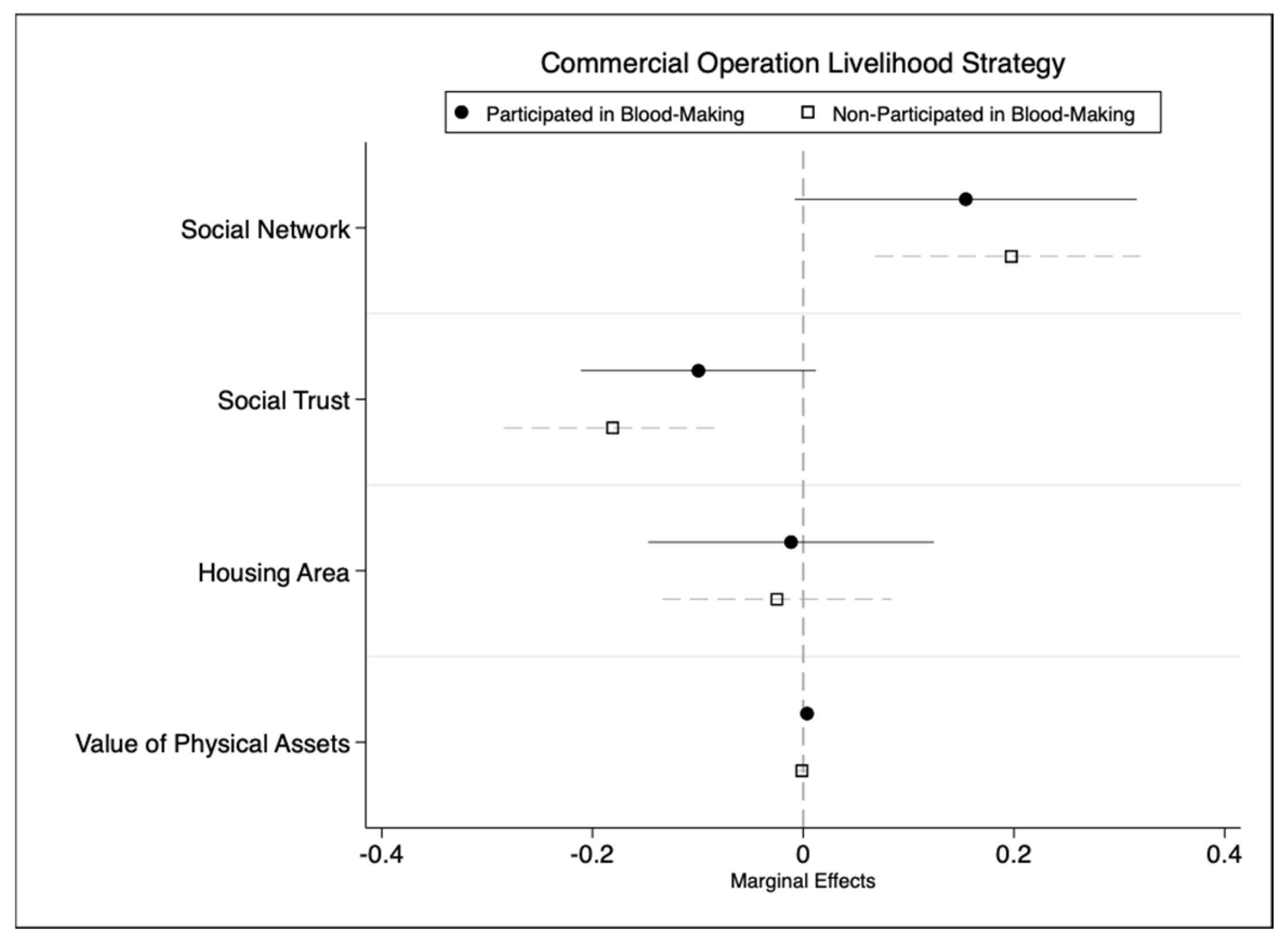

- Analysis of the Moderating Effect of “Blood-Transfusion” Forest Ecological Compensation Policies on the Relationship between Farmers’ Livelihood Capital and Their Livelihood Strategies (Table 5).First, the moderating effect of “blood-making” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between social capital and the out-migration for work livelihood strategy (Figure 8). The two dimensions of social capital show markedly different patterns. On the one hand, social networks consistently exhibit an “anchoring” effect: regardless of policy participation, a one-unit increase in social network level significantly reduces the probability of out-migration (by 12.9 percentage points in the non-participation group and 16.2 percentage points in the participation group). After participating in the “blood-making” policy, this constraining effect strengthened by about 25.6%, indicating that the policy enhances the cohesive force of local social networks, further retaining labor within Wuyi Mountain National Park. On the other hand, social trust shows a “driving” effect, but its potency is weakened by the policy: in the absence of the policy, a one-unit increase in social trust raises the probability of out-migration by 12.2%; after policy participation, this driving effect diminishes to 7.2%, a reduction of about 41%. This suggests that the formal cooperation and information channels provided by the “blood-making” policy partially substitute for the traditional reliance on generalized social trust to obtain external employment information. Therefore, Hypothesis H3a receives only partial support: while the policy indeed weakens the driving effect of social trust, it does not alter the direction of the anchoring effect of social networks.Second, the moderating effect of “blood-making” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between physical capital and the out-migration for work livelihood strategy (Figure 8). The influence of physical capital varies by indicator. Housing area, as a stock-based wealth indicator, shows a significant pull effect on labor outflow when farmers do not participate in the policy (marginal effect = 0.086, significant at the 10% level), suggesting that households with better housing conditions may have more economic slack to support members seeking opportunities elsewhere. However, after participating in the “blood-making” policy, this pull effect disappears entirely and slightly reverses (–0.003, insignificant). A possible explanation is that the policy enhances the attractiveness and feasibility of local livelihoods through industrial support, so that households no longer need to “crowd out” labor through migration to optimize resource allocation, thereby dissolving the link between housing-area-represented wealth stock and migration decisions. The value of physical assets does not affect out-migration decisions in either group, indicating that the quantity of production tools and equipment per se does not directly promote or inhibit labor mobility, regardless of policy intervention. Overall, Hypothesis H3b receives partial support: the “blood-making” policy weakens the driving effect of “non-productive” physical capital (represented by household wealth stock) on out-migration, but its effect on productive physical assets remains insignificant.Third, the moderating effect of “blood-making” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between social capital and the commercial operation livelihood strategy (Figure 9). Social networks have a significantly positive effect on the commercial operation strategy in both groups, consistent with the theoretical expectation that social networks provide market information and business opportunities (as posited in H3c). However, the positive effect in the participation group (0.154) is smaller than in the non-participation group (0.197), and the significance level is lower. This indicates that participation in the “blood-making” policy does not strengthen the promotional effect of social networks on commercial operation; rather, it slightly attenuates it. Social trust shows a significantly negative effect in both groups, and the negative effect is weaker in the participation group (–0.099) than in the non-participation group (–0.181). This suggests that, regardless of policy participation, a higher level of social trust is associated with a lower probability of choosing commercial operation. A possible reason is that, in Wuyi Mountain National Park, social trust is more embedded in traditional, non-market mutual-aid relationships rather than oriented towards riskier commercial activities; alternatively, households with high trust may prefer stable production modes and hold conservative attitudes toward market risks.Fourth, the moderating effect of “blood-making” forest ecological compensation policies on the relationship between physical capital and the commercial operation livelihood strategy (Figure 9). Regarding housing area, both the participation and non-participation groups show an insignificant negative effect on the commercial operation strategy, with confidence intervals including zero. This indicates that, irrespective of policy participation, housing size has no statistically significant promotional effect on choosing the commercial operation strategy. This does not align with the theoretical expectation that housing, as a fixed asset, could support business operations—likely because housing area reflects living conditions and residential assets rather than directly productive fixed assets for commercial activities. However, the role of the value of physical assets changes under policy intervention: in the non-participation group its effect is weak and insignificant (–0.001); after policy participation, it shows a significant positive driving effect, with each 10,000-yuan increase in asset value raising the probability of commercial operation by an average of 0.4 percentage points (significant at the 10% level). This shift suggests that the core of the “blood-making” policy lies in its accompanying industrial support and market linkages, which can transform farmers’ dormant, general-purpose physical assets into specialized productive capital suitable for specific green industries, thereby significantly enhancing the marginal productivity and commercial conversion rate of physical assets. Consequently, Hypothesis H3d is supported in the dimension of physical asset value but not in the dimension of housing area. All research hypotheses and their corresponding test results are presented in Table 6.

4.4. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Research Implications

5.3. Limitations

- First, the use of cross-sectional data can only reflect policy effects at a specific point in time; it cannot capture the dynamic evolution of farmers’ livelihood capital or the long-term impacts of policies, making it difficult to reveal the temporal adjustment patterns of livelihood strategies. Future research could employ longitudinal panel data to track the long-term evolution of policy effects and enhance data reliability by cross-verifying policy participation with administrative records.

- Second, information on participation in FECPs relied on farmers’ self-reporting, which may be subject to recall or perception biases. Meanwhile, the measurement of social capital and financial capital still has room for improvement—for example, the structural characteristics of social networks and variations in credit-constraint intensity were not considered, which may affect the precision of the results.

- Third, the sample focused solely on Wuyi Mountain National Park, and the generalizability of the conclusions needs to be further tested in protected areas with different property-rights regimes and industrial structures. Future studies could expand the scope of research and compare policy implementation effects across regions with different tenure systems and industrial types to clarify the applicable boundaries and optimization directions of FECPs.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The configuration of farmers’ livelihood capital significantly influences their choice of livelihood strategy, with different dimensions of capital playing distinct roles.

- (2)

- “Blood-transfusion” and “blood-making” FECPs exhibit differentiated moderating effects on the relationship between livelihood capital and livelihood strategies. “Blood-transfusion” policies, relying primarily on direct cash compensation, function to “fill gaps and stabilize livelihoods”. They significantly mitigate the driving force of insufficient natural and financial capital on out-migration for work and provide initial financial support for low-barrier commercial activities.

- (3)

- “Blood-making” policies, through productive investment and organizational empowerment, achieve “activation and transformation”. They effectively activate the commercial production attributes of physical assets, driving local commercial operations. Simultaneously, they reshape the functions of social capital, enhancing its local cohesion while partially substituting its traditional role in external connections.

- (4)

- Overall, the two policy types play complementary roles in sustainable livelihood transition: “Blood-transfusion” FECPs focus on protective security, safeguarding the livelihood baseline and preventing poverty induced by conservation; “Blood-making” policies emphasize transformative empowerment, fostering endogenous drivers and promoting the development of eco-friendly industries.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

- First, implement a targeted compensation system characterized by “categorized interventions and orderly linkage”. The design of FECPs should be differentiated based on the livelihood capital status of farming households. For vulnerable groups, ensure the timely and full disbursement of “blood-transfusion” funds to solidify the livelihood foundation underlying ecological conservation. For households with certain resources and development potential, increase “blood-making” investments and ensure effective linkage, guiding their transition toward ecological industrialization through industrial support, skills training, and market connections, thereby cultivating an endogenous mechanism that mutually reinforces conservation and development.

- Second, innovate and establish a “blood-transfusion” FECP allocation mechanism combining “collective coordination with household-level benefits”. Given the property rights feature of Wuyi Mountain National Park, where collective forests account for about two-thirds of the area, village collectives should coordinate a portion of the compensation funds for improving shared infrastructure such as tea processing facilities and ecotourism trails within the forest area. The remaining funds should then be distributed to households according to their forest tenure shares. This approach avoids the problems of low per-household compensation amounts and weak policy effects while balancing collective interests with individual rights.

- Third, optimize the design of “blood-making” policies to strengthen the formation of productive capital. Industrial subsidies and equipment support should focus on areas that can generate specialized ecological production capital, such as smart forestry facilities and standardized renovations for eco-homestays. Concurrently, enhance the cultivation of new types of business entities like cooperatives and family forest farms, emphasizing their organic integration with local social networks. These entities should serve as comprehensive platforms for resource integration, market linkage, and risk diversification, rather than simply replacing traditional forms of cooperation.

- Fourth, establish and improve dynamic monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management mechanisms for FECPs. Given the long-term and complex nature of FECP effects, a comprehensive monitoring network covering livelihood capital, strategy choices, ecological outcomes, and community perceptions should be developed. Regular policy evaluations should be conducted, paying particular attention to the heterogeneous impacts of policies on different capital dimensions and social groups. Based on evaluation results, dynamically optimize compensation standards, target groups, and methods to achieve adaptive policy management, ensuring ongoing alignment with the dual objectives of community development and ecological conservation in national parks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Riordan, T. Protecting beyond the protected. In Biodiversity, Sustainability and Human Communities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Berghöfer, U.; Berghöfer, A. Participation’in Development Thinking—Coming to Grips with a Truism and its Critiques. In Stakeholder Dialogues in Natural Resources Management: Theory and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Hull, V.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Polasky, S.; et al. Strengthening protected areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N. (Ed.) Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; CIFOR Occasional Paper: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005; Volume 42, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Arcenas, A.; Platais, G. Can Payments for Environmental Services Help Reduce Poverty? An Exploration of the Issues and the Evidence to Date from Latin America. World Dev. 2004, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laundré, J.W.; Hernández, L.; Altendorf, K.B. Wolves, elk, and bison: Reestablishing the” landscape of fear” in Yellowstone National Park, USA. Can. J. Zool. 2001, 79, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Can nature-based tourism benefits compensate for the costs of national parks? A study of the Bavarian Forest National Park, Germany. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia, P. Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Parks Aust. 2019, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Nyahongo, J.W.; Tingstad, K.M. The nature of hunting around the western corridor of Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2005, 51, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Rojas, S.J.; Whitworth, A.; Paredes-Garcia, J.A.; Pillco-Huarcaya, R.; Whittaker, L.; Huaypar-Loayza, K.H.; MacLeod, R. Indigenous lands are better for amphibian biodiversity conservation than immigrant-managed agricultural lands: A case study from Manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 15, 19400829221134811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M. Is tourism always beneficial? A case study from Masai Mara national reserve, Narok, Kenya. Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2014, 15, 458–483. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, B. The dual nature of parks: Attitudes of neighbouring communities towards Kruger National Park, South Africa. Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tang, X.; Du, A.; Zang, Z.H.; Xu, W.H. Scientific construction of national parks: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Natl. Parks. 2023, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Sang, W. Policy framework and key technologies for ecological compensation in national parks. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Su, Y. Research on basic legal issues of ecological compensation mechanism: Taking biodiversity protection in Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve as example. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2006, 1, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Su, Y.; Cui, G. Quantitative scheme for ecological compensation in nature reserves: Based on “virtual land” calculation method. J. Nat. Resour. 2011, 26, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, A.; Fan, S.; Lu, Y.; Chi, M.; Liao, L. Comparative study on optimization and integration schemes for county-level nature reserves based on cost-benefit assessment: Case study in Taining County, Fujian Province. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 2020–2037. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Jin, C.; Su, Y.; Zhu, C.; Yuan, S. The impact of ecological compensation policy differences on farmers’ employment and income. China Land Sci. 2024, 38, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, W. The impact of sloping land conversion program policy choices on farmers’ income: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin sandstorm source control project. China Econ. Q. 2007, 1, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Si, R.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q. The impact of livestock and poultry ban policy on alternative livelihood strategies and farmers’ income. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 643–654. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, W.; Feng, W.; Li, S. The impact of relocation on farmers’ livelihood strategies: Based on a survey of Ankang area in Southern Shaanxi. China Rural. Surv. 2013, 6, 31–44+93. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Xu, K.; Jin, L. The impact of wetland ecological compensation on farmers’ livelihood strategies and income: Evidence from Poyang Lake region. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 72–80+108. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Chen, C.; He, Y. The impact of herders’ household asset endowment on their livelihood risk: Based on a survey in Qilian Mountain National Park. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2021, 29, 2817–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Liao, Q.; Xie, G. The impact of livelihood capital of hog-quitting farmers on their risk of production transformation and employment shift. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2019, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Lin, Y.; Ren, L.; Sun, G.; Gao, J. The impact of public welfare forest ecological compensation policy on forest farmers’ livelihood strategies and income. Issues For. Econ. 2023, 43, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Lu, L.; Cheng, H.; Yu, H. Research progress and prospect of the interaction between watershed ecological compensation and rural residents’ sustainable livelihoods. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Pang, G.; Ji, H.; Li, M. The utility of national park construction in improving farmers’ well-being: A case study of the Giant Panda National Park. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 10560–10572. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qi, X. Research on the impact of wildlife-inflicted damage on farmers’ livelihoods in Wuyishan National Park. Sichuan J. Zool. 2022, 41, 434–443. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Yue, Z. Livelihood capital, livelihood risk and farmers’ livelihood strategies. Issues Agric. Econ. 2012, 33, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q. Research status and key future directions of sustainable livelihoods. Adv. Earth Sci. 2015, 30, 823–833. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Farmers’ livelihood capital and the choice of livelihood strategies. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 14, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Pu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L. Study on the relationship between livelihood capital and livelihood strategies: A case study of Ganzhou District in Zhangye City. China Population. Resour. Environ. 2009, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.X.; Jiang, J.H.; Xing, G. Ecological compensation rewards and penalties, environmental governance competition, and differentiated policy effects. China Soft Sci. 2025, 40, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, J. Construction of a differentiated ecological compensation value assessment model for forest parks. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2022, 50, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Y.N. Ecological compensation: Conceptual evolution, analysis, and some thoughts. Environ. Prot. 2018, 46, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Xu, F.; Qi, Y.Y. From ‘sharing the same river water’ to ‘jointly protecting the same river water’: Changes in farmers’ employment and income under the Xin’anjiang ecological compensation. Manag. World 2022, 38, 102–124. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Definition and Assignment | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Livelihood Strategy | Pure agricultural | Traditional farming/forestry as main livelihood activity | ||

| Outmigration for work | Non-farm work as main livelihood activity | ||||

| Commercial Operation | Self-run business as main livelihood activity | ||||

| Explanatory Variable | Human Capital | Education Level | Years of formal education received by household head (1 = illiterate/primary school, 2 = junior high school, 3 = senior high/vocational secondary school, 4 = college, 5 = undergraduate and above) | 2.36 | 0.85 |

| Health Status | Average health status of family members (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = general, 4 = good, 5 = excellent) | 3.81 | 1.03 | ||

| Natural Capital | Tea Garden Area | Contracted tea garden area of the household (mu) | 15.63 | 21.16 | |

| Bamboo Forest Area | Contracted moso bamboo forest area of the household (mu) | 20.04 | 142.78 | ||

| Social Capital | Social Network | Abundance of social relations available for support (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = general, 4 = good, 5 = excellent) | 4.13 | 0.65 | |

| Social Trust | Trust in village collectives, neighbors and markets (1 = very untrustworthy, 2 = untrustworthy, 3 = general, 4 = trustworthy, 5 = very trustworthy) | 3.88 | 0.92 | ||

| Physical Capital | Housing Area | Owned residential and production building area (1 ≤ 50 m2, 2 = 50–100 m2, 3 = 100–150 m2, 4 ≥ 150 m2) | 3.47 | 0.73 | |

| Value of Physical Assets | Value of production fixed assets such as agricultural machinery, processing equipment, and transportation tools (10,000 yuan) | 23.00 | 33.19 | ||

| Financial Capital | Loan Convenience | Difficulty of obtaining loans from banks, credit unions and other financial institutions (1 = inconvenient, 2 = general, 3 = convenient) | 2.62 | 0.86 | |

| Household Income | Total income from various sources of the household in the past year (10,000 yuan) | 27.82 | 60.82 | ||

| Moderating Variable | Forest Ecological Compensation Policy | “Blood-transfusion” Forest Ecological Compensation Policy | Participation in the “blood-transfusion” forest ecological compensation policy (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.40 | 0.49 |

| “Blood-making” Forest Ecological Compensation Policy | Participation in the “blood-making” forest ecological compensation policy (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.44 | 0.50 | ||

| Control Variables | Individual Characteristics | Age | Actual age of the household head (years) | 50.38 | 13.10 |

| Gender | Gender of the household head (0 = female, 1 = male) | 0.79 | 0.41 | ||

| Household Characteristics | Number of Laborers | Number of family members with labor capacity (person) | 3.53 | 1.33 | |

| Livelihood Strategy | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Agricultural Type | 76 | 31.80 | 31.80 |

| Outmigration for Work Type | 49 | 20.50 | 52.30 |

| Commercial Operation Type | 114 | 47.70 | 100.00 |

| Livelihood Capital | Indicator | Outmigration for Work (Pure Agricultural Type as Reference) | Commercial Operation (Pure Agricultural Type as Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Education Level | 0.069 (0.224) | 0.100 (0.191) |

| Health Status | 0.269 (0.168) | 0.240 * (0.142) | |

| Natural Capital | Tea Garden Area | −0.047 ** (0.019) | −0.008 (0.008) |

| Bamboo Forest Area | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | |

| Social Capital | Social Network | −0.598 ** (0.288) | 0.333 (0.222) |

| Social Trust | 0.383 * (0.223) | −0.285 * (0.170) | |

| Physical Capital | Housing Area | 0.279 (0.217) | 0.153 (0.181) |

| Value of Physical Assets | 0.008 (0.009) | 0.012 * (0.006) | |

| Financial Capital | Loan Convenience | 0.204 (0.237) | 0.140 (0.202) |

| Household Income | −0.023 (0.015) | 0.004 (0.005) | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0103 | ||

| Wald chi2 | 45.51 | ||

| Log likelihood | −212.838 | ||

| Outmigration for Work | Commercial Operation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated in Blood-Transfusion | Non-Participated in Blood-Transfusion | Participated in Blood-Transfusion | Non-Participated in Blood-Transfusion | ||

| Natural Capital | Tea Garden Area | −0.004 [−0.016, 0.007] | −0.008 ** [−0.015, 0.001] | −0.009 [−0.021, 0.003] | 0.002 [−0.003, 0.007] |

| Bamboo Forest Area | 0.001 [−0.000, 0.001] | −0.006 [−0.015, 0.002] | −0.001 [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.009 ** [0.001, 0.019] | |

| Financial Capital | Loan Convenience | 0.042 [−0.072, 0.155] | −0.016 [−0.111, 0.078] | −0.064 [−0.179, 0.052] | 0.128 * [−0.001, 0.257] |

| Household Income | 0.002 [−0.006, 0.010] | −0.009 ** [−0.016, −0.001] | 0.024 *** [0.015, 0.033] | 0.005 ** [0.001, 0.009] | |

| Sample | N = 86 | N = 153 | N = 86 | N = 153 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.237 | 0.069 | 0.237 | 0.069 | |

| Wald chi2 | 30.78 | 37.41 | 30.78 | 37.41 | |

| Log likelihood | −54.298 | −124.651 | −54.298 | −124.651 | |

| Outmigration for Work | Commercial Operation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated in Blood-Making | Non-Participated in Blood-Making | Participated in Blood-Making | Non-Participated in Blood-Making | ||

| Social Capital | Social Network | −0.162 *** [−0.284, −0.040] | −0.129 ** [−0.250, −0.009] | 0.154 * [−0.008, 0.317] | 0.197 *** [0.068, 0.327] |

| Social Trust | 0.072 * [−0.006, 0.150] | 0.122 ** [0.022, 0.222] | −0.099 * [−0.211, 0.120] | −0.181 *** [−0.284, 0.078] | |

| Physical Capital | Housing Area | −0.003 [−0.096, 0.091] | 0.086 * [−0.011, 0.183] | −0.012 [−0.147, 0.124] | −0.025 [−0.134, 0.084] |

| Value of Physical Assets | 0.001 [−0.003, 0.003] | −0.001 [−0.004, 0.004] | 0.004 * [0.001, 0.007] | −0.001 [−0.006, 0.003] | |

| Sample | N = 106 | N = 133 | N = 106 | N = 133 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.4493 | 0.1166 | 0.4493 | 0.1166 | |

| Wald chi2 | 26.25 | 34.78 | 26.25 | 34.78 | |

| Log likelihood | −79.659 | −118.942 | −79.659 | −118.942 | |

| Hypothesis No. | Hypothesis Content | Verification Result |

|---|---|---|

| H2a | “Blood-transfusion” FECPs will weaken the positive driving effect of insufficient natural capital on the out-migration for work strategy. | Supported |

| H2b | “Blood-transfusion” FECPs will weaken the positive driving effect of scarce financial capital on the out-migration for work strategy. | Supported |

| H2c | “Blood-transfusion” FECPs will weaken the positive driving effect of natural capital on the commercial operation strategy. | Supported |

| H2d | “Blood-transfusion” FECPs will strengthen the positive supporting effect of financial capital on the commercial operation strategy. | Supported |

| H3a | “Blood-making” FECPs will weaken the positive driving effect of social capital on the out-migration for work strategy. | Partially Supported |

| H3b | “Blood-making” FECPs will weaken the positive driving effect of insufficient physical capital on the out-migration for work strategy. | Partially Supported |

| H3c | “Blood-making” FECPs will strengthen the positive driving effect of social capital on the commercial operation strategy. | Not Supported |

| H3d | “Blood-making” FECPs will strengthen the positive driving effect of physical capital on the commercial operation strategy. | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, C.; Huang, H.; Sun, X.; Su, S. Impact of Forest Ecological Compensation Policy on Farmers’ Livelihood: A Case Study of Wuyi Mountain National Park. Forests 2026, 17, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010053

Pan C, Huang H, Sun X, Su S. Impact of Forest Ecological Compensation Policy on Farmers’ Livelihood: A Case Study of Wuyi Mountain National Park. Forests. 2026; 17(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010053

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Chuyuan, Hongbin Huang, Xiaoxia Sun, and Shipeng Su. 2026. "Impact of Forest Ecological Compensation Policy on Farmers’ Livelihood: A Case Study of Wuyi Mountain National Park" Forests 17, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010053

APA StylePan, C., Huang, H., Sun, X., & Su, S. (2026). Impact of Forest Ecological Compensation Policy on Farmers’ Livelihood: A Case Study of Wuyi Mountain National Park. Forests, 17(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010053