Boosting Tree Stem Sectional Volume Predictions Through Machine Learning-Based Stem Profile Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Ground-Truth Data

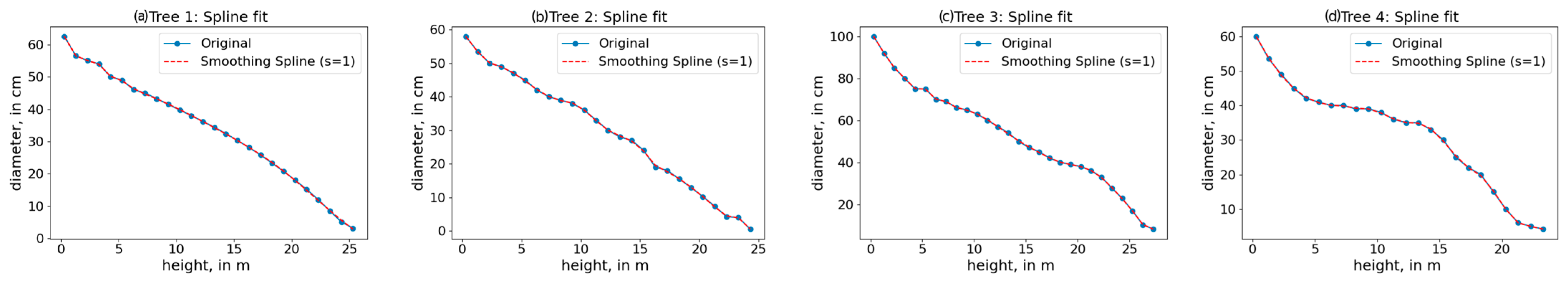

2.2. Data Exploration

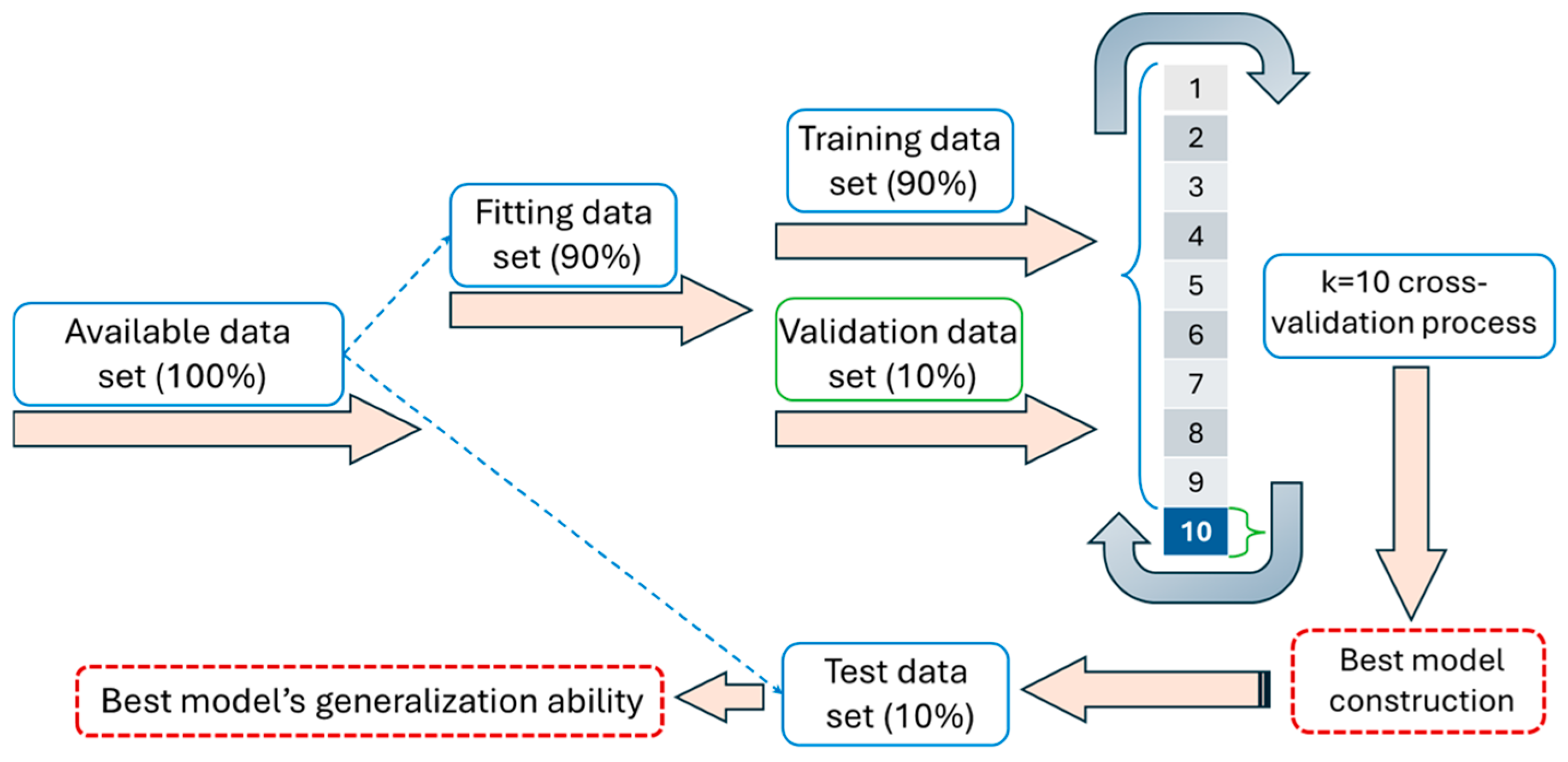

2.3. Data Handling

2.4. Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) Modeling

2.5. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Modeling

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

- (a)

- The root mean square error (RMSE):

- (b)

- The percentage root mean square error (RMSE%), expressed as the percentage error of the observed values average:

- (c)

- The correlation coefficient:

- (d)

- The average absolute error (AAE):

- (e)

- Relative (i) estimation/prediction and (ii) residuals plots

3. Results

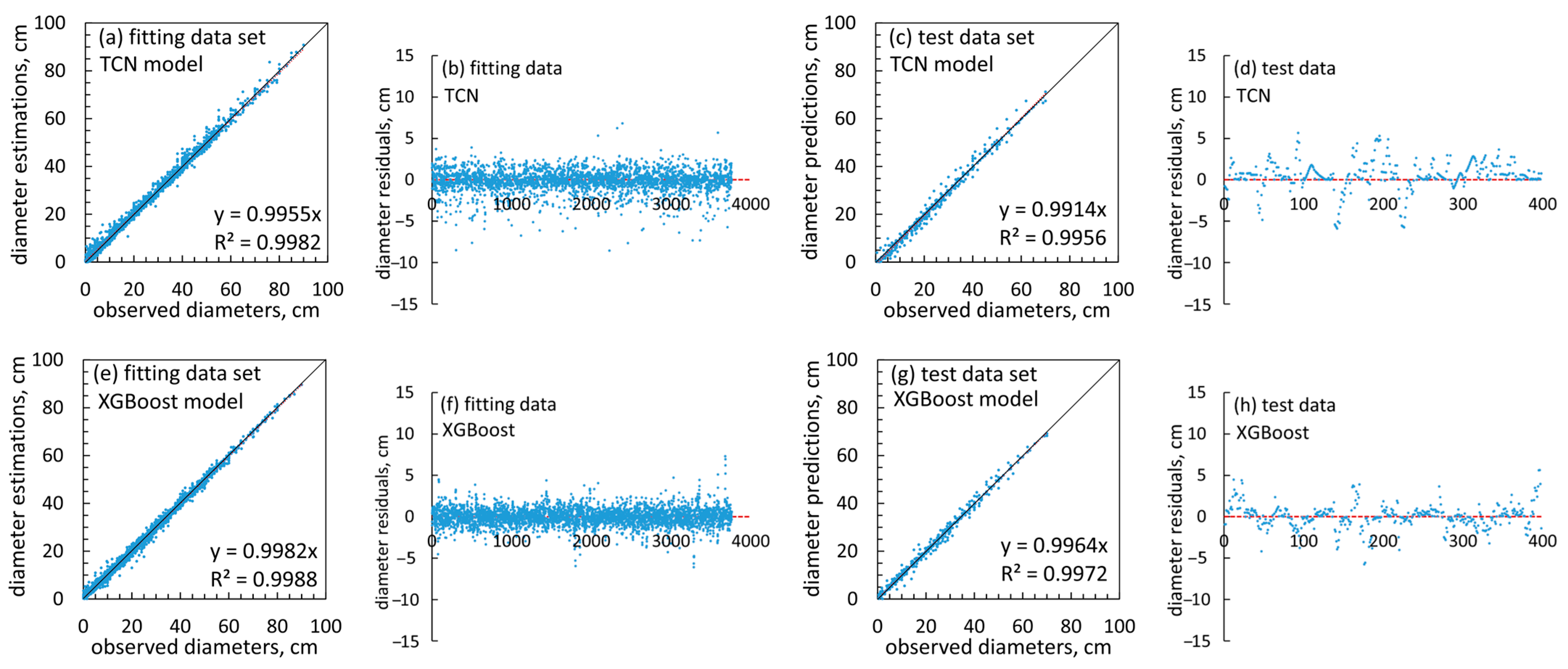

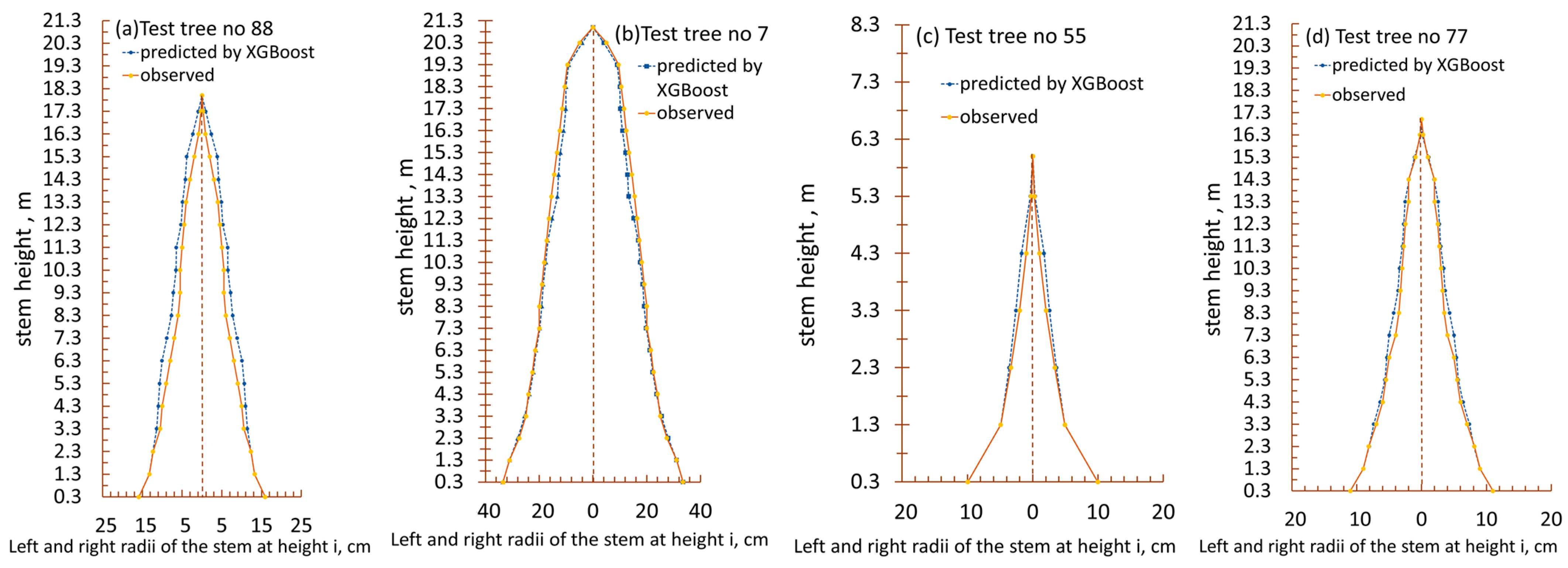

3.1. Stem Diameter Modeling

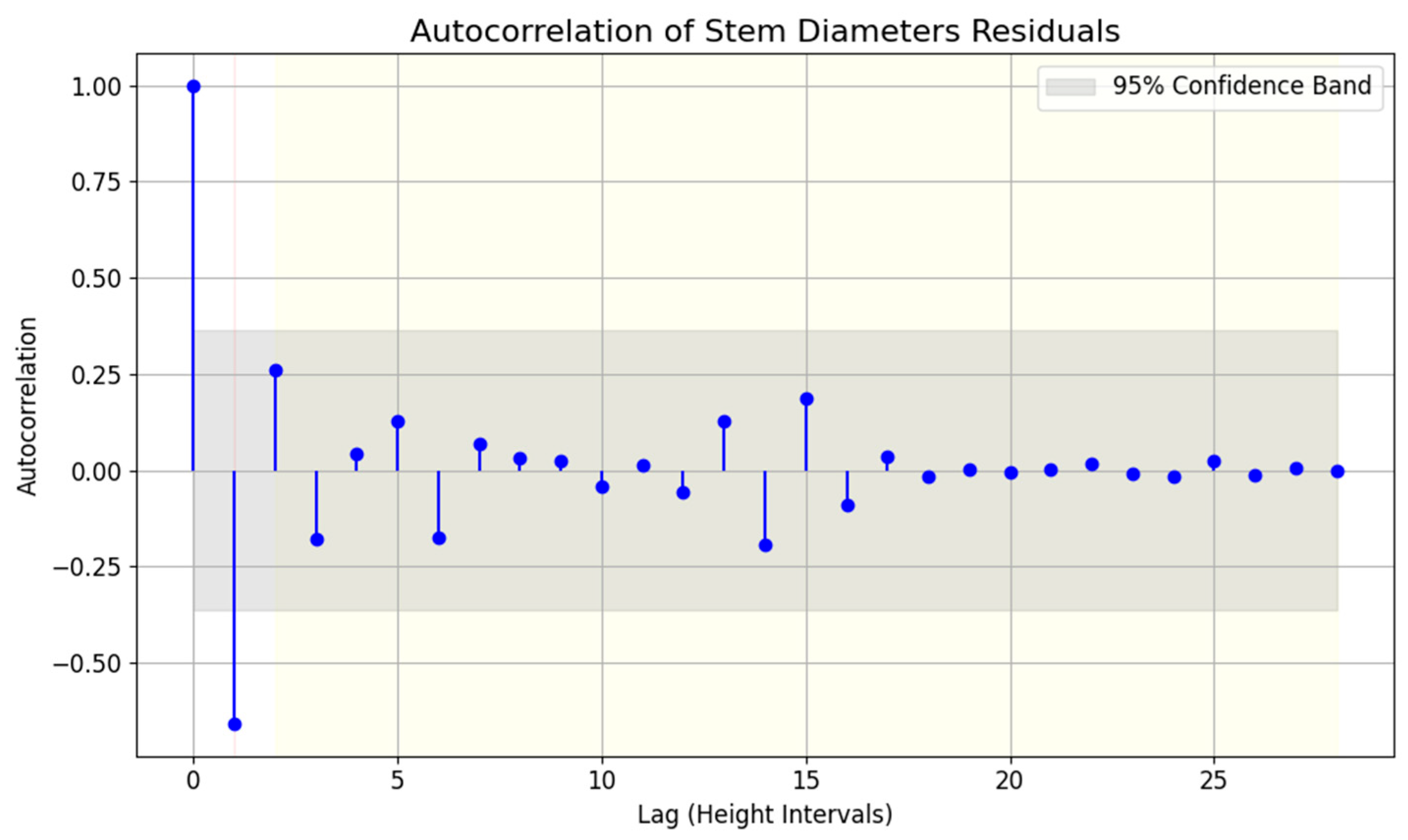

3.1.1. Autocorrelation

3.1.2. Machine Learning Modeling

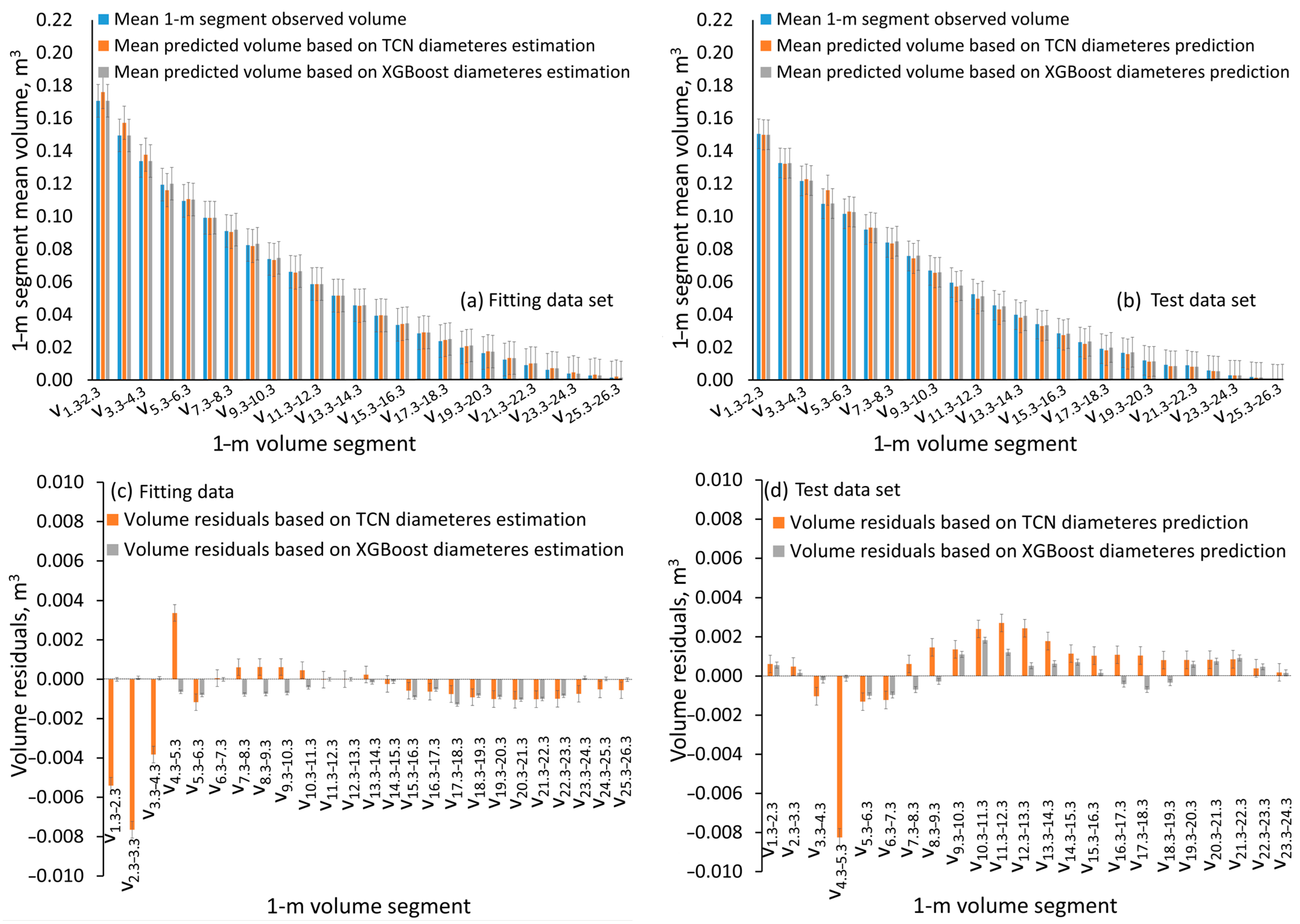

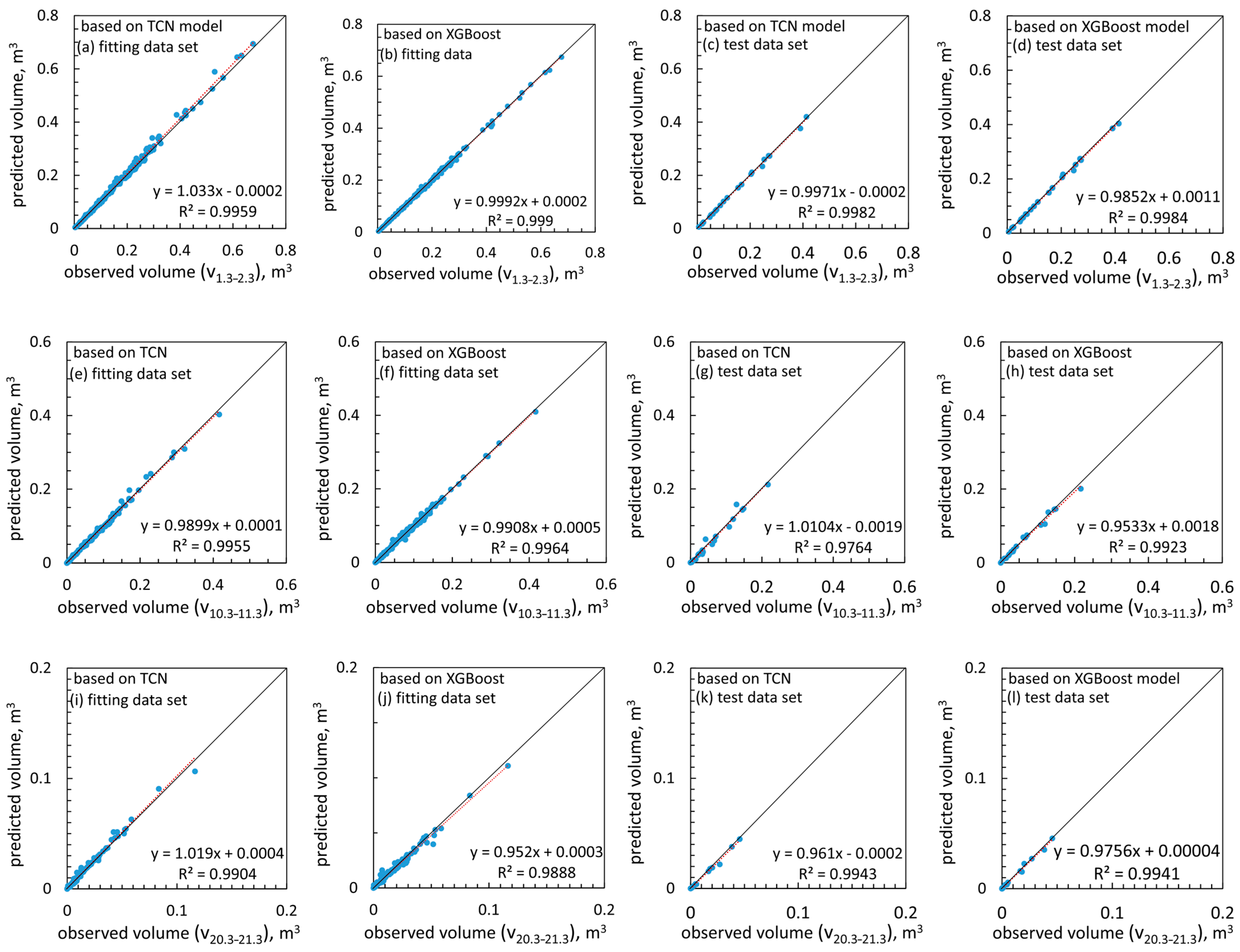

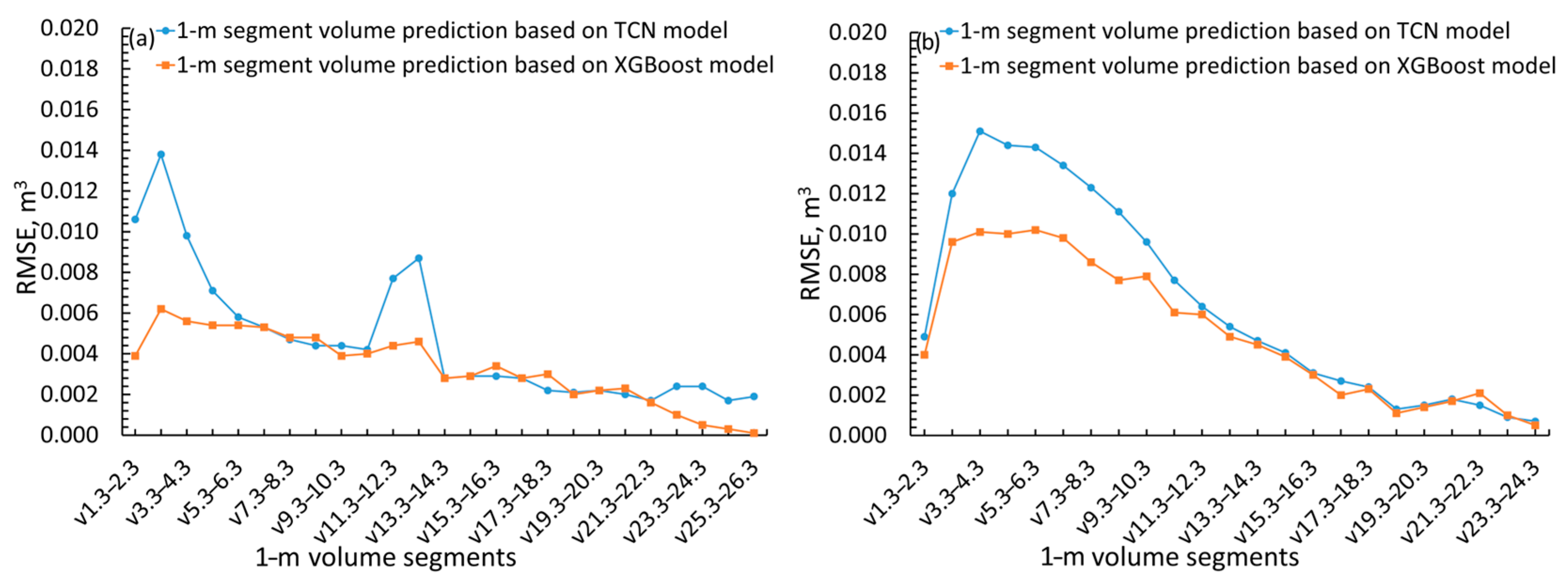

3.2. Total and Segmented Stem Volume Prediction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAE | Average absolute error |

| ACF | Autocorrelation function |

| ADF | Augmented Dickey–Fuller |

| batch_size | batch_size |

| CCANN | Cascade correlation artificial neural network |

| CNNs | Convolutional neural networks |

| d0.3 | Stump diameter |

| d1.3 | Breast height diameter |

| dmax | depth of each tree |

| EDA | Exploratory data analysis |

| ELU | Exponential linear unit |

| epochs | the number of full pass |

| kernel | kernel size |

| KPSS | Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin |

| l | learning rate in TCN |

| lr | learning rate in XGBoost |

| mcw | parameter regulating the splitting to child node |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| ndt | decision trees |

| num_filters | Number of filters per layer |

| reg_lambda | regularization term |

| ReLU | Rectified linear unit |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| RMSE% | Percentage root mean square error |

| RNNs | Recurrent neural networks |

| SELU | Scaled exponential linear unit |

| Sigmoid | Sigmoid function |

| Tanh | Hyperbolic tangent function |

| TCN | Temporal convolutional network |

| TCNs | Temporal convolutional networks |

| tht | Total tree height |

| vi–j | Segmented stem volume from i to j meters stem height above ground |

| vtot | Total stem volume |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

| γ | Gamma hyperparameter |

References

- Trincado, G.; Burkhart, H.E. A generalized approach for modeling and localizing stem profile curves. For. Sci. 2006, 52, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.W. Tree and Forest Measurement, 3rd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, J.A., Jr.; Ducey, M.J.; Beers, T.W.; Husch, B. Forest Mensuration, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, H.E.; Tomé, M. Modeling Forest Trees and Stands; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salekin, S.; Catalán, C.H.; Boczniewicz, D.; Phiri, D.; Morgenroth, J.; Meason, D.F.; Mason, E.G. Global Tree Taper Modelling: A Review of Applications, Methods, Functions, and Their Parameters. Forests 2021, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaerschalk, J.P. Converting volume equations to compatible taper equations. For. Sci. 1972, 18, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, T.A.; Burkhart, H.E. Segmented polynomial regression applied to taper equations. For. Sci. 1976, 18, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, A. A variable-exponent taper equation. Can. J. For. Res. 1988, 18, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, A. My last words on taper equations. For. Chron. 2004, 80, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, G.; Ung, C.H.; Fortin, M.; Guo, X.J.; Lampert, M.C.; Ruel, J.C. A simple stem taper model with mixed effects for boreal black spruce. Eur. J. Forest Res. 2009, 128, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, R.; Alkan, O. Fitting and calibrating a mixed-effects segmented taper model for brutian pine. Cerne 2020, 26, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Guo, H.; Jia, W.; Wang, F. Analysis of Taper Functions for Larix olgensis Using Mixed Models and TLS. Forests 2021, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R.; Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Özçelik, R.; Cao, Q.V.; Trincado, G.; Göçer, N. Predicting tree height from tree diameter and dominant height using mixed-effects and quantile regression models for two species in Turkey. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 419–420, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, M.J.; Özçelik, R.; Eler, Ü.; Koparan, B. From Regression to Machine Learning: Modeling Height–Diameter Relationships in Crimean Juniper Stands Without Calibration Overhead. Forests 2025, 16, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, M.J. Assessing a reliable modeling approach of features of trees through neural network models for sustainable forests. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2012, 2, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wu, D.; Zhou, R.; Fang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lou, X. Estimation of DBH at Forest Stand Level Based on Multi-Parameters and Generalized Regression Neural Network. Forests 2019, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercanlı, İ. Innovative deep learning artificial intelligence applications for predicting relationships between individual tree height and diameter at breast height. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ao, Z.; Jia, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, K. A geographically weighted deep neural network model for research on the spatial distribution of the down dead wood volume in Liangshui National Nature Reserve (China). iForest 2021, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.H.; Görgens, E.B. Artificial Intelligence Procedures for Tree Taper Estimation within a Complex Vegetation Mosaic in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, R.; Diamantopoulou, M.J.; Trincado, G. Evaluation of potential modeling approaches for Scots pine stem diameter prediction in north-eastern Turkey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, S.; Acuña, E. Stem Taper Estimation Using Artificial Neural Networks for Nothofagus Trees in Natural Forest. Forests 2022, 13, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Kang, J.; Lim, C.; Kim, D.; Lee, M. Application of Machine Learning Models in the Estimation of Quercus mongolica Stem Profiles. Forests 2025, 16, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağlam, F. Machine learning-based stem taper model: A case study with Brutian pine. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2025, 8, 1609549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, M.J.; Özçelik, R.; Kalkanli Genç, Ş. Evaluation of the random forest regression machine learning technique as an alternative to ecoregional based regression taper modelling. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, A.; Akça, A. Forest Mensuration; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, R.H. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications, 2nd ed.; PWS-Kent: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cywicka, D.; Jakóbik, A.; Socha, J.; Pasichnyk, D.; Widlak, A. Modelling bark thickness for Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and common oak (Quercus robur L.) with recurrent neural networks. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luković, M.; Zweifel, R.; Thiry, G.; Zhang, C.; Schubert, M. Reconstructing radial stem size changes of trees with machine. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20220349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, A.; Butt, M. Improved sap flow prediction: A comparative deep learning study based on LSTM, BiLSTM, LRCN, and GRU with stem diameter data. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Webb, G.I.; Petitjean, F. Temporal Convolutional Neural Network for the Classification of Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantavichai, R.; Turnblom, E.C. Identifying non-thrive trees and predicting wood density from resistograph using temporal convolution network. For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 18, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Huang, C.; Dou, P.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J. Fine-scale forest classification with multi-temporal sentinel-1/2 imagery using a temporal convolutional neural network. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2457953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Dong, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Estimating Individual Tree Height and Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) from Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) Data at Plot Level. Forests 2018, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Mason, E.; Xu, C.; Morgenroth, J. Estimating individual tree DBH and biomass of durable Eucalyptus using UAV LiDAR. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 89, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíndola, R.P.; Picanço, M.M.; de Andrade, L.P.; Ebecken, N.F.F. Applications of Machine Learning Methods in Sustainable Forest Management. Climate 2025, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, B.; Morneau, A.; LeBel, L.; Gautam, S.; Cyr, G.; Tremblay, R.; Carle, J.-F. An XGBoost-Based Machine Learning Approach to Simulate Carbon Metrics for Forest Harvest Planning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidis, D.; Moschopoulos, G.; Mouratidis, A.; Styllas, M.; Tsimerikas, A.; Deligiannis, V.-K.; Voutsis, N.; Perivolioti, T.-M.; Vergos, G.S.; Plachtova, A. Revisiting the determination of Mount Olympus Height (Greece). J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Service of Elassona, Greece. Forest Management Plan for the Public Forest of Karya, Management Period 2014–2023; Municipality of Elassona, Forest Service of Elassona: Elassona, Greece, 2015. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou, M.J.; Georgakis, A. Improving European Black Pine Stem Volume Prediction Using Machine Learning Models with Easily Accessible Field Measurements. Forests 2024, 15, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, F.A. Adaptive cluster sampling for forest inventories. For. Sci. 1993, 39, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, P.A. Spatial Sampling. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Kempf-Leonard, Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 29.01; Released 2023; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou, M.J. Filling gaps in diameter measurements on standing tree boles in the urban forest of Thessaloniki, Greece. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway, R.H.; Stoffer, D.S. Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With R Examples, 4th ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H.O.A. A Study in the Analysis of Stationary Time Series, 2nd ed.; Almqvist & Wiksell: Stockholm, Sweden, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Likelihood Ratio Statistics for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Econometrica 1981, 49, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, D.; Phillips, P.C.B.; Schmidt, P.; Shin, Y. Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. J. Econom. 1992, 54, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendt, F.; de Miguel-Diez, F.; Wallor, E.; Blasko, L.; Cremer, T. Comparison of different approaches to estimate bark volume of industrial wood at disc and log scale. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, H.E.; Avery, T.E.; Bullock, B.P. Forest Measurements, 6th ed.; Waveland Pr Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.L.; Delen, D. Advanced Data Mining Techniques; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, C.; Vidal, R.; Reiter, A.; Hager, G.D. Temporal Convolutional Networks: A Unified Approach to Action Segmentation. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Hua, G., Jégou, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9915, pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.R.; Singh, S.K.; Chaudhuri, B.B. Activation functions in deep learning: A comprehensive survey and benchmark. Neurocomputing 2022, 503, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, Version 3.13; Python Software Foundation: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2023. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3.13/index.html (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the KDD ’16: 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Granada, Spain, 12–15 December 2011; pp. 2546–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S. Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator: Understanding Its Algorithm Components and Their Roles for Better Empirical Performance. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2304.11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormerod, D.W. A simple bole model. For. Chron. 1973, 49, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, R.; Brooks, J.R. Compatible volume and taper models for economically important tree species of Turkey. Ann. For. Sci. 2012, 69, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șahin, A. Analyzing regression models and multi-layer artificial neural network models for estimating taper and tree volume in Crimean pine forests. iForest 2024, 17, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedel, S. Stochastic stem bucking using mixture density neural networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.00510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Std. Error of the Mean | Std. Deviation | Variable | Mean | Std. Error of the Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitting data set | |||||||

| d0.3 | 50.8080 | 1.3307 | 18.8186 | v12.3–13.3 | 0.0513 | 0.0032 | 0.0439 |

| d1.3 | 45.0015 | 1.2401 | 17.5370 | v13.3–14.3 | 0.0457 | 0.0029 | 0.0392 |

| tht | 20.5825 | 0.3599 | 5.0893 | v14.3–15.3 | 0.0392 | 0.0026 | 0.0346 |

| vtot | 1.5769 | 0.0905 | 1.2794 | v15.3–16.3 | 0.0338 | 0.0023 | 0.0302 |

| v0.3–1.3 | 0.2068 | 0.0102 | 0.1445 | v16.3–17.3 | 0.0286 | 0.0021 | 0.0265 |

| v1.3–2.3 | 0.1707 | 0.0088 | 0.1241 | v17.3–18.3 | 0.0237 | 0.0018 | 0.0232 |

| v2.3–3.3 | 0.1495 | 0.0078 | 0.1102 | v18.3–19.3 | 0.0199 | 0.0017 | 0.0202 |

| v3.3–4.3 | 0.1333 | 0.0070 | 0.0993 | v19.3–20.3 | 0.0166 | 0.0015 | 0.0173 |

| v4.3–5.3 | 0.1194 | 0.0065 | 0.0914 | v20.3–21.3 | 0.0125 | 0.0014 | 0.0146 |

| v5.3–6.3 | 0.1095 | 0.0061 | 0.0847 | v21.3–22.3 | 0.0092 | 0.0012 | 0.0122 |

| v6.3–7.3 | 0.0992 | 0.0057 | 0.0790 | v22.3–23.3 | 0.0062 | 0.0010 | 0.0096 |

| v7.3–8.3 | 0.0912 | 0.0053 | 0.0736 | v23.3–24.3 | 0.0040 | 0.0009 | 0.0075 |

| v8.3–9.3 | 0.0826 | 0.0049 | 0.0681 | v24.3–25.3 | 0.0028 | 0.0008 | 0.0056 |

| v9.3–10.3 | 0.0740 | 0.0046 | 0.0631 | v25.3–26.3 | 0.0016 | 0.0006 | 0.0034 |

| v10.3–11.3 | 0.0662 | 0.0042 | 0.0579 | v26.3–27.3 | 0.0013 | 0.0006 | 0.0021 |

| v11.3–12.3 | 0.0587 | 0.0037 | 0.0501 | v27.3–28.3 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 |

| Test data set | |||||||

| d0.3 | 47.1636 | 4.0679 | 19.0802 | v10.3–11.3 | 0.0596 | 0.0116 | 0.0518 |

| d1.3 | 41.4364 | 3.8596 | 18.1029 | v11.3–12.3 | 0.0525 | 0.0103 | 0.0463 |

| tht | 19.8955 | 1.1662 | 5.4698 | v12.3–13.3 | 0.0457 | 0.0093 | 0.0417 |

| vtot | 1.3725 | 0.2565 | 1.2033 | v13.3–14.3 | 0.0400 | 0.0085 | 0.0379 |

| v0.3–1.3 | 0.1807 | 0.0287 | 0.1348 | v14.3–15.3 | 0.0343 | 0.0077 | 0.0344 |

| v1.3–2.3 | 0.1505 | 0.0251 | 0.1177 | v15.3–16.3 | 0.0286 | 0.0069 | 0.0307 |

| v2.3–3.3 | 0.1327 | 0.0226 | 0.1060 | v16.3–17.3 | 0.0233 | 0.0059 | 0.0265 |

| v3.3–4.3 | 0.1162 | 0.0203 | 0.0950 | v17.3–18.3 | 0.0193 | 0.0052 | 0.0226 |

| v4.3–5.3 | 0.1029 | 0.0183 | 0.0861 | v18.3–19.3 | 0.0167 | 0.0048 | 0.0191 |

| v5.3–6.3 | 0.1017 | 0.0175 | 0.0782 | v19.3–20.3 | 0.0121 | 0.0039 | 0.0150 |

| v6.3–7.3 | 0.0920 | 0.0166 | 0.0741 | v20.3–21.3 | 0.0094 | 0.0035 | 0.0120 |

| v7.3–8.3 | 0.0842 | 0.0158 | 0.0707 | v21.3–22.3 | 0.0091 | 0.0032 | 0.0090 |

| v8.3–9.3 | 0.0759 | 0.0147 | 0.0657 | v22.3–23.3 | 0.0059 | 0.0022 | 0.0058 |

| v9.3–10.3 | 0.0670 | 0.0130 | 0.0583 | v23.3–24.3 | 0.0030 | 0.0012 | 0.0033 |

| Hyperparameters for the TCN Model | ||||||

| num_filters | kernel | dilation_rate | learning_rate | batch_size | epochs | |

| range | [64–128] | [1–5] | 1 | [0.001–0.1] | [16–64] | [30–100] |

| step | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.0001 | 8 | 5 |

| optimal value | 128 | 2 | 1 | 0.0036 | 16 | 80 |

| Hyperparameters for the XGBoost Model | ||||||

| ndt | lr | dmax | mcw | reg_lambda | γ | |

| range | [100–200] | [0.10–0.30] | [1–6] | [0–2] | [0–5] | [0–5] |

| step | 5 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| optimal value | 185 | 0.28 | 5 | 1 | 1.44 | 0.11 |

| Fitting Data Set | ||||

| models | RMSE, cm | RMSE% | R | AAE, cm |

| TCN | 1.2650 | 5.0930 | 0.9968 | 0.8819 |

| XGBoost | 1.0371 | 4.1757 | 0.9978 | 0.7526 |

| Test Data Set | ||||

| TCN | 1.8672 | 7.9404 | 0.9936 | 1.2681 |

| XGBoost | 1.4836 | 6.3091 | 0.9952 | 1.0204 |

| Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCN | XGBoost | |||||

| RMSE, m3 | R | AAE, m3 | RMSE, m3 | R | AAE, m3 | |

| range, m3 | Fitting data set | |||||

| <1.0 | 0.0179 | 0.9984 | 0.0130 | 0.0162 | 0.9993 | 0.0087 |

| [1.0–2.0) | 0.0402 | 0.9917 | 0.0284 | 0.0306 | 0.9930 | 0.0192 |

| [2.0–3.0) | 0.0356 | 0.9942 | 0.0262 | 0.0422 | 0.9883 | 0.0252 |

| [3.0–6.0) | 0.6573 | 0.9958 | 0.0840 | 0.0496 | 0.9997 | 0.0332 |

| Test data set | ||||||

| <1.0 | 0.0389 | 0.9968 | 0.0314 | 0.0324 | 0.9939 | 0.0255 |

| [1.0–4.3) | 0.1697 | 0.9835 | 0.1267 | 0.0910 | 0.9952 | 0.0820 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diamantopoulou, M.J. Boosting Tree Stem Sectional Volume Predictions Through Machine Learning-Based Stem Profile Modeling. Forests 2026, 17, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010054

Diamantopoulou MJ. Boosting Tree Stem Sectional Volume Predictions Through Machine Learning-Based Stem Profile Modeling. Forests. 2026; 17(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiamantopoulou, Maria J. 2026. "Boosting Tree Stem Sectional Volume Predictions Through Machine Learning-Based Stem Profile Modeling" Forests 17, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010054

APA StyleDiamantopoulou, M. J. (2026). Boosting Tree Stem Sectional Volume Predictions Through Machine Learning-Based Stem Profile Modeling. Forests, 17(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010054