Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- New pathways in distribution identification: This study proposed a multi-rule image synthesis strategy tailored for intertidal scenarios (including the kernel normalized difference vegetation index (KNDVI)/normalized difference water index (NDWI)/enhanced vegetation index (EVI)/mangrove forest index (MFI) and annual median isoquanti synthesis rules), integrated with the Res-UNet deep-learning algorithm. This approach achieved high-precision mapping of Hainan’s mangrove forests from 2019 to 2023, mitigating the spatiotemporal instability and misclassification issues caused by cloud cover and tidal interference [31,35,37,45].

- Structure–function parameter coupling inversion: By integrating Sentinel-1/2 spectral, textural, and index features, this study compared the canopy height estimation performance of machine-learning algorithms, including XGBoost, GBDT, and RF. Canopy height was then incorporated as a key feature into AGC inversion, thereby bridging the “structure–function” chain [22,23,26,27,28,36,46,47,48,49,50,51].

- Empirical constraints and multi-year assessment: By constructing high-quality training and validation samples using UAV and plot-based surveying, this study conducted a synergistic assessment of Hainan’s mangrove area, structure, and carbon stocks from 2019 to 2023. The study quantified the spatiotemporal variation and sources of uncertainty during the restoration period, providing a baseline and methodological framework for regional blue carbon accounting and refined conservation strategies.

- Scalability for management applications: This study established a technical workflow that combines temporal stability with algorithmic reusability, thereby providing a reference for operational monitoring and cross-regional comparative studies in other mangrove areas across tropical and subtropical regions.

- Explicitly embedding multi-rule temporal synthesis into deep-learning mapping workflows substantially enhances the stability and accuracy of distribution identification in complex intertidal zones.

- Using canopy height as a bridge for AGC inversion, the effectiveness of coupling structural and functional information in blue carbon assessment was validated.

- Providing a comprehensive assessment of the distribution, structure, and carbon storage of Hainan mangrove forests over multiple years through a multi-scale observation loop integrating UAVs, plot surveys, and satellite imagery. This study provides technical support and regional evidence chains for quantifying ecological restoration outcomes and evaluating blue carbon policies.

2. Materials and Methods

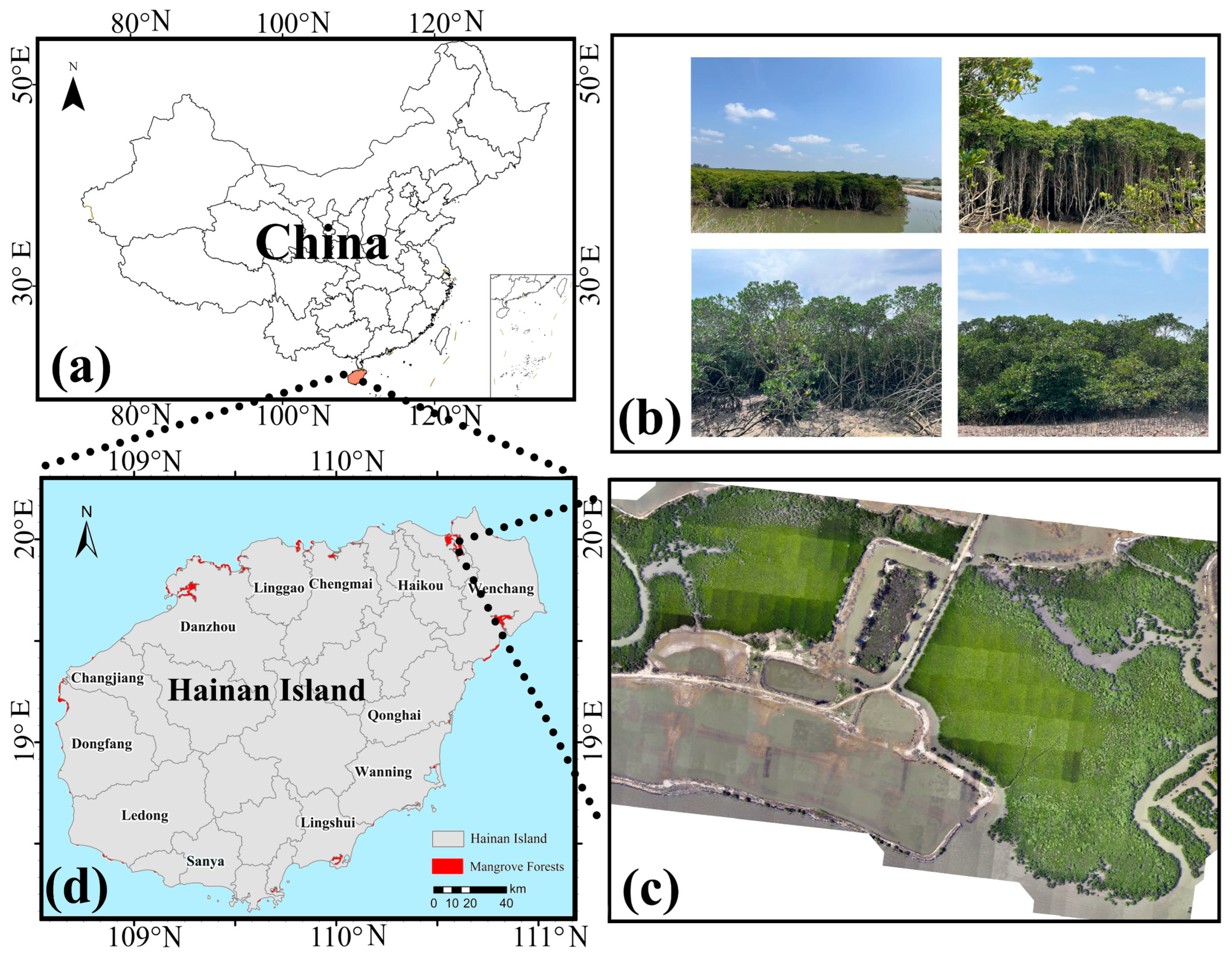

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Forest Sample Plot Data

2.2.2. Remote Sensing Data

- Google Earth imagery integrates data from multiple satellite and aerial sources, including WorldView, GeoEye-1, and QuickBird, achieving spatial resolutions as high as 0.3 m. It delivers sub-meter spatial accuracy and 16-bit radiometric resolution [55]. The imagery underwent geometric correction, orthorectification, and atmospheric radiation correction by using the WGS_1984_Web_Mercator projection (EPSG:3857) with a planar positioning error of less than 2 pixels. This study used multitemporal cloud-free imagery (average cloud cover < 5%) covering the mangrove distribution areas on Hainan Island from 2019 to 2023 for precise mangrove boundary identification and manual feature verification. Although this dataset offers high spatial resolution, its spectral range is limited to the visible band. Consequently, multispectral data must be integrated to supplement vegetation index and cover estimation.

- The Sentinel-1 series constitutes a vital component of the European Space Agency’s Copernicus program and comprises the twin-satellite systems Sentinel-1A and Sentinel-1B, which possess all-weather and all-time observation capabilities. This study utilizes vertical–vertical (VV) and vertical–horizontal (VH) dual-polarization data acquired in the Interferometric Wide Swath (IW) mode, featuring a spatial resolution of 5 m × 20 m and a swath width of 250 km. Following the decommissioning of Sentinel-1B in 2021, the data acquired after 2023 were obtained solely from Sentinel-1A. Using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform, the COPERNICUS/S1_GRD dataset covering the Hainan mangrove area from 2018 to 2023 was acquired. A Level-1 pre-processing workflow was executed, which encompassed thermal noise removal, radiometric calibration, and geometric correction. All data were resampled to a 10 m resolution in the WGS84 projection (EPSG:4326). Subsequently, a −30 dB threshold filter and mask function were applied to eliminate pixels with low signal-to-noise ratio. The spatiotemporal mean composite images were then calculated based on the VV/VH polarization bands. To reduce short-term environmental variability, including tidal fluctuations in intertidal mangrove environments, multi-temporal Sentinel-1 composites were constructed using all available observations within each year. This compositing strategy helps to average radar backscatter responses across different tidal stages, thereby reducing the influence of extreme low- or high-tide conditions on individual acquisitions. This process ultimately generated a 128-scene SAR composite image covering the potential distribution zone of the Hainan mangrove forests, thereby providing scattering characteristic information for subsequent canopy structure inversion.

- The Sentinel-2 twin-satellite system comprises Sentinel-2A (launched in June 2015) and Sentinel-2B (launched in March 2017), each equipped with a multispectral imager (MSI). This instrument features 13 spectral bands (443–2190 nm) covering the visible light, red-edge, near-infrared, and shortwave-infrared regions, with a revisit period of 5 d. The red-edge bands (B5–B8A) exhibited high sensitivity to chlorophyll content variations, whereas the shortwave infrared bands (B11 and B12) were suitable for canopy structure and water content inversion. This study used Level-2A surface reflectance products (COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARMONIZED) that underwent atmospheric correction and orthorectification via the Sen2Cor algorithm. The reflectance values ranged from 0 to 1, with coordinates in the WGS84 coordinate system. On the GEE platform, imagery with a cloud cover < 30% from 2018 to 2023 was selected. The cloud-contaminated pixels were removed using a QA60 band cloud mask. To ensure spatial consistency, the 20 m bands (B5–B8A, B11, B12) were resampled to a 10 m resolution using nearest neighbor interpolation, aligning them with the 10 m bands (B2–B4, B8). Annual cloud-free reflectance images were generated using the median composite method. Similar to the Sentinel-1 processing, these indices were generated from multi-temporal image composites rather than single-date observations, which helps to mitigate variability introduced by different tidal stages in intertidal mangrove environments. Subsequently, 11 bands were stacked within the ENVI 5.6 software to compute 17 vegetation indices (including NDVI, SAVI, MSAVI, MTCI) and 88 texture features based on the grey-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) (including mean, contrast, entropy, correlation). This yielded a high-dimensional, multi-source dataset comprising 116 features that provided input variables for mangrove distribution identification, canopy height inversion, and carbon stock estimation (Table 1).

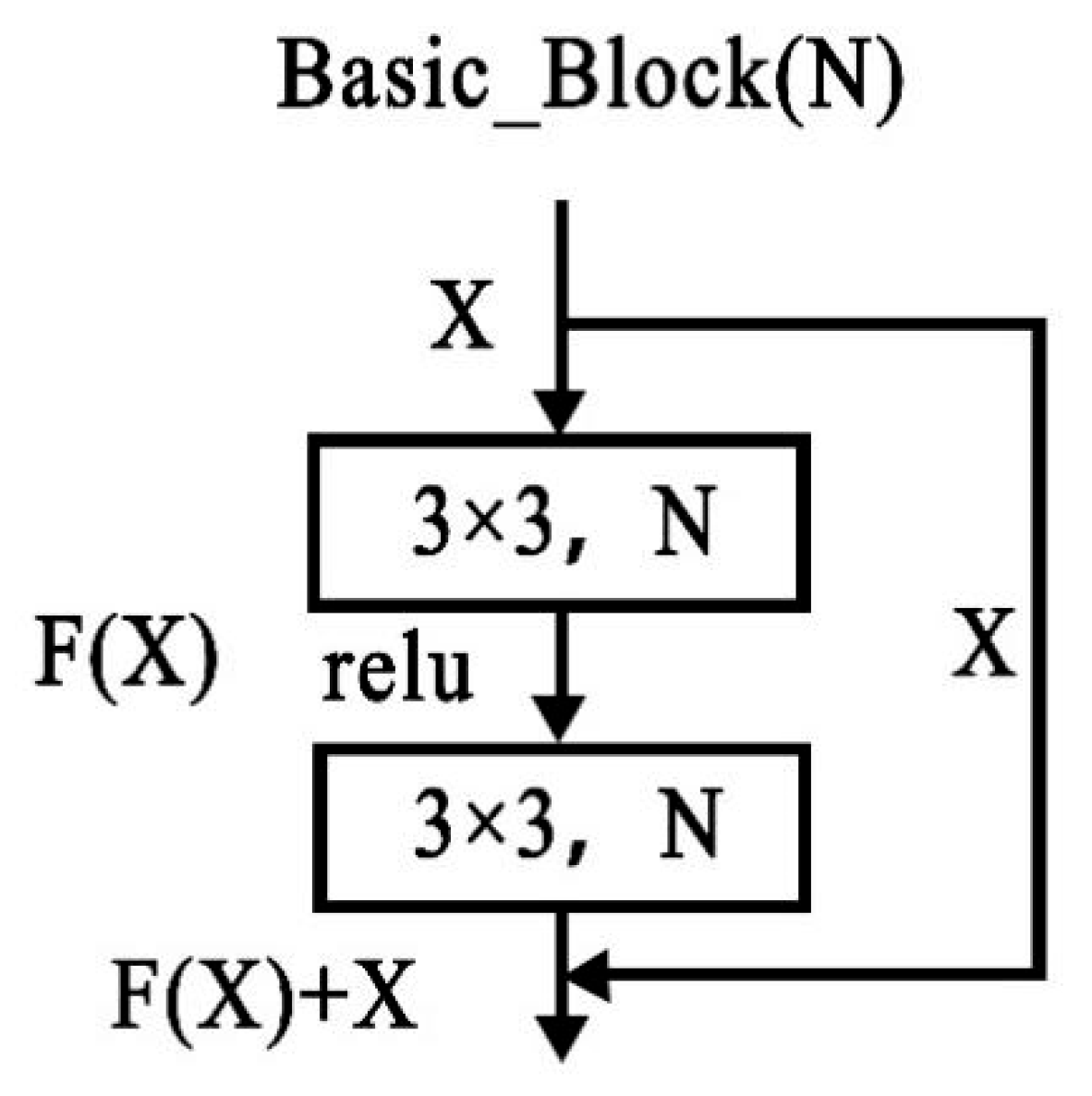

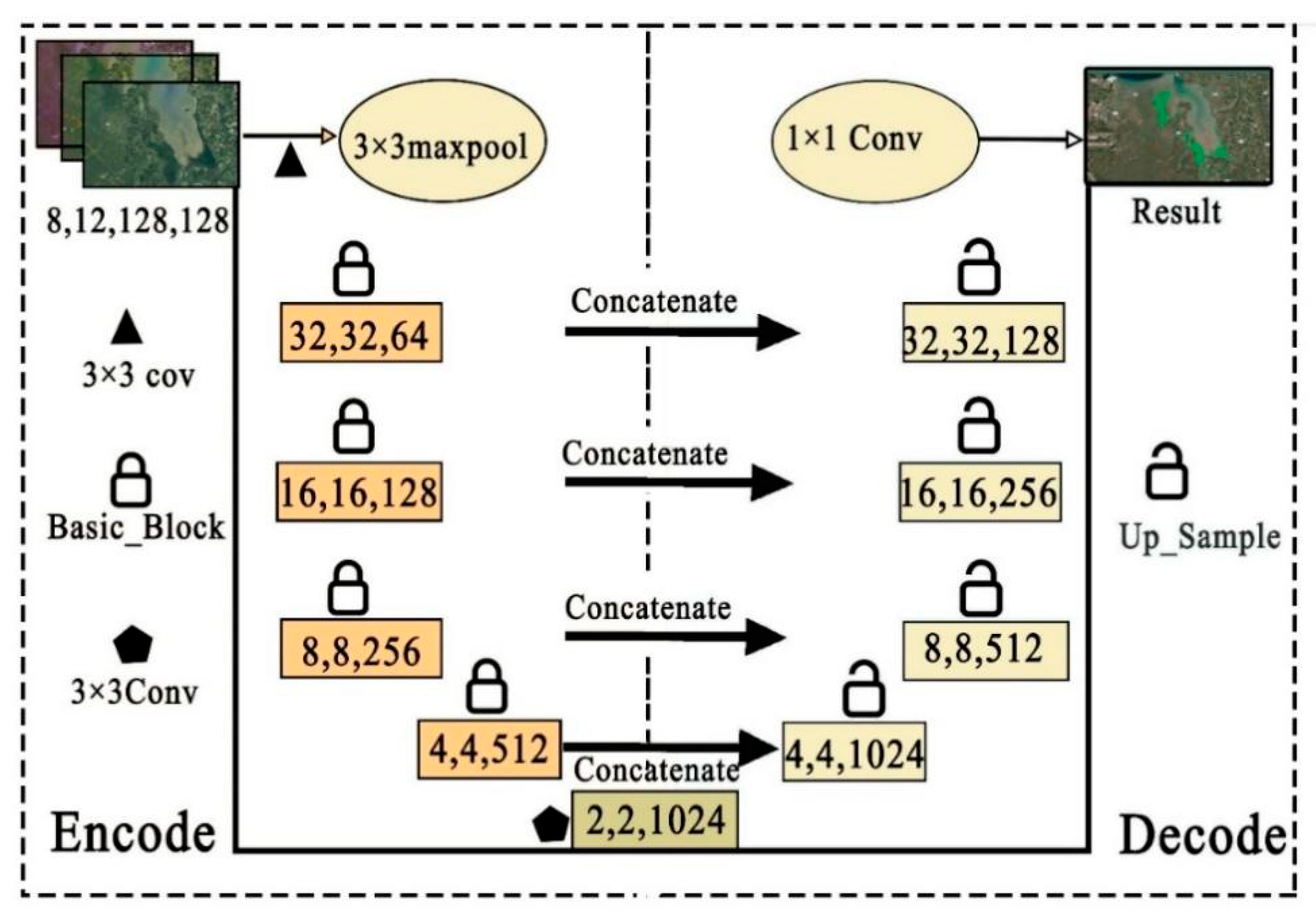

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Multi-Rule Synthesis Method for Remote Sensing Images

2.3.2. Estimation of Mangrove Canopy Height and Aboveground Carbon Storage

3. Results

3.1. Distribution Range of Mangroves in Hainan

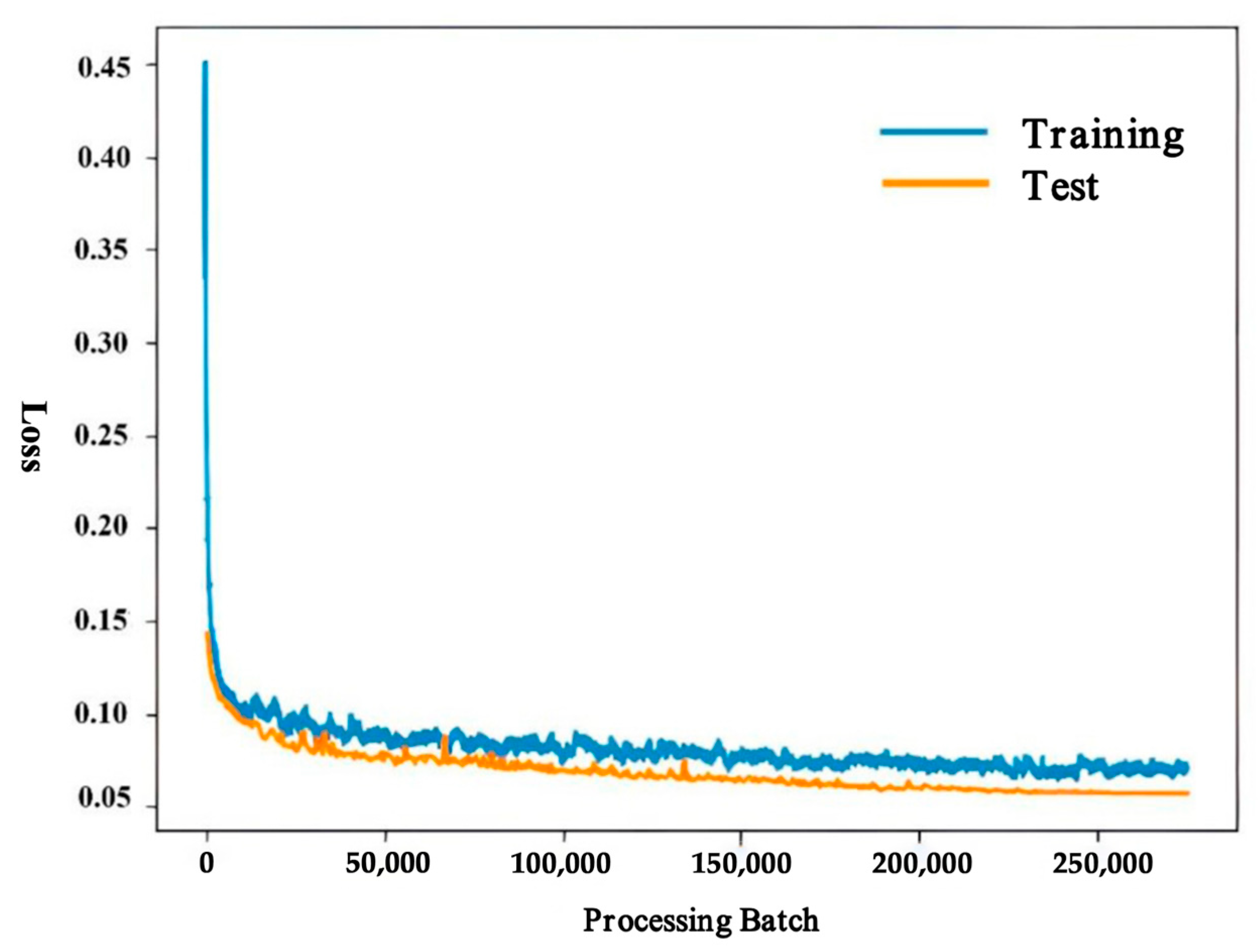

3.1.1. Results of Mangrove Distribution Identification in Hainan

3.1.2. Model Accuracy Validation and Result Evaluation

3.1.3. Analysis of Distribution Patterns in Mangrove Forests

3.2. Accuracy Verification Results

3.2.1. Validation Results for Canopy Height Modeling Accuracy

3.2.2. Validation Results for Aboveground Carbon Storage Modeling Accuracy

3.3. Changes in Canopy Height of Hainan Mangroves, 2019–2023

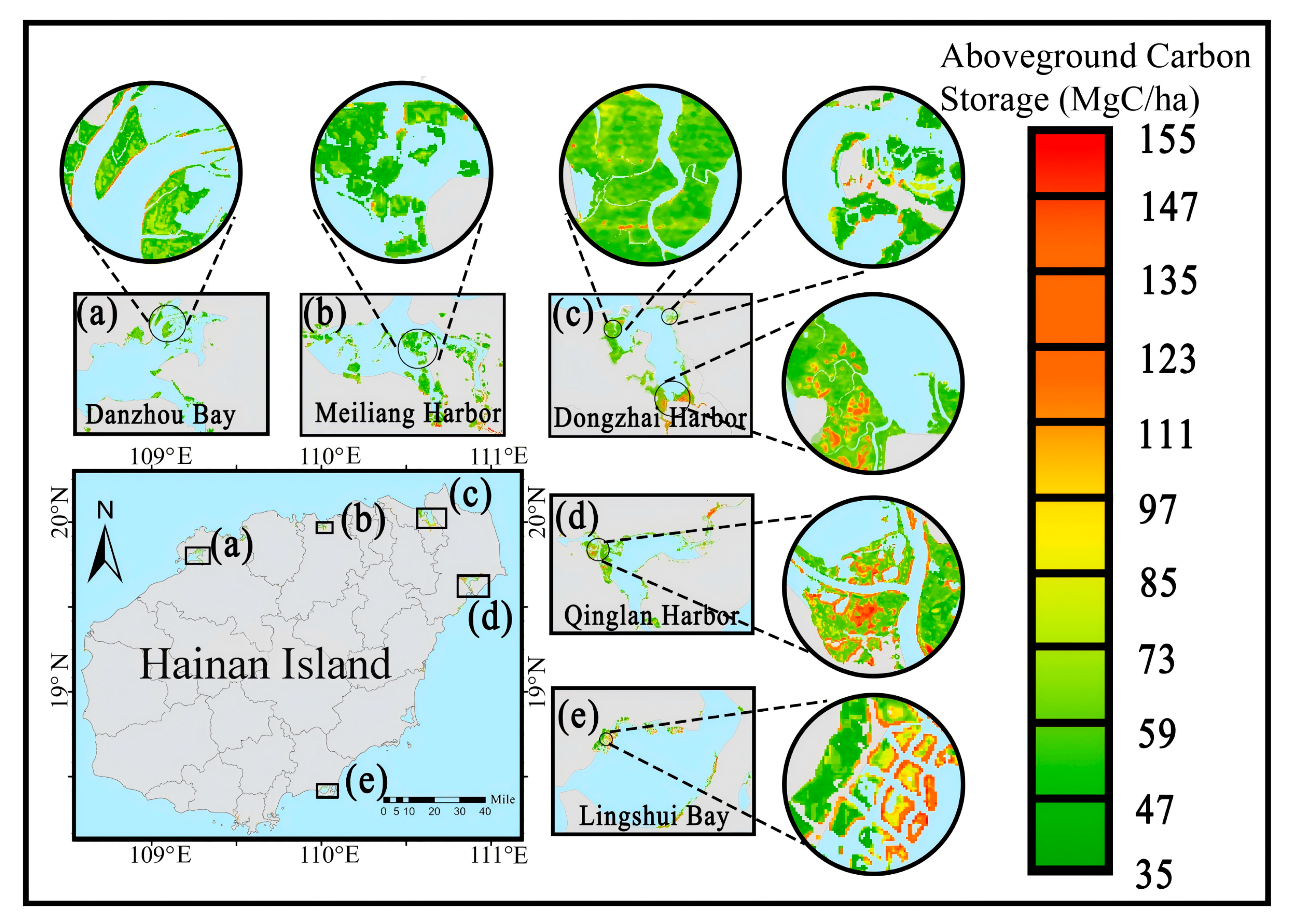

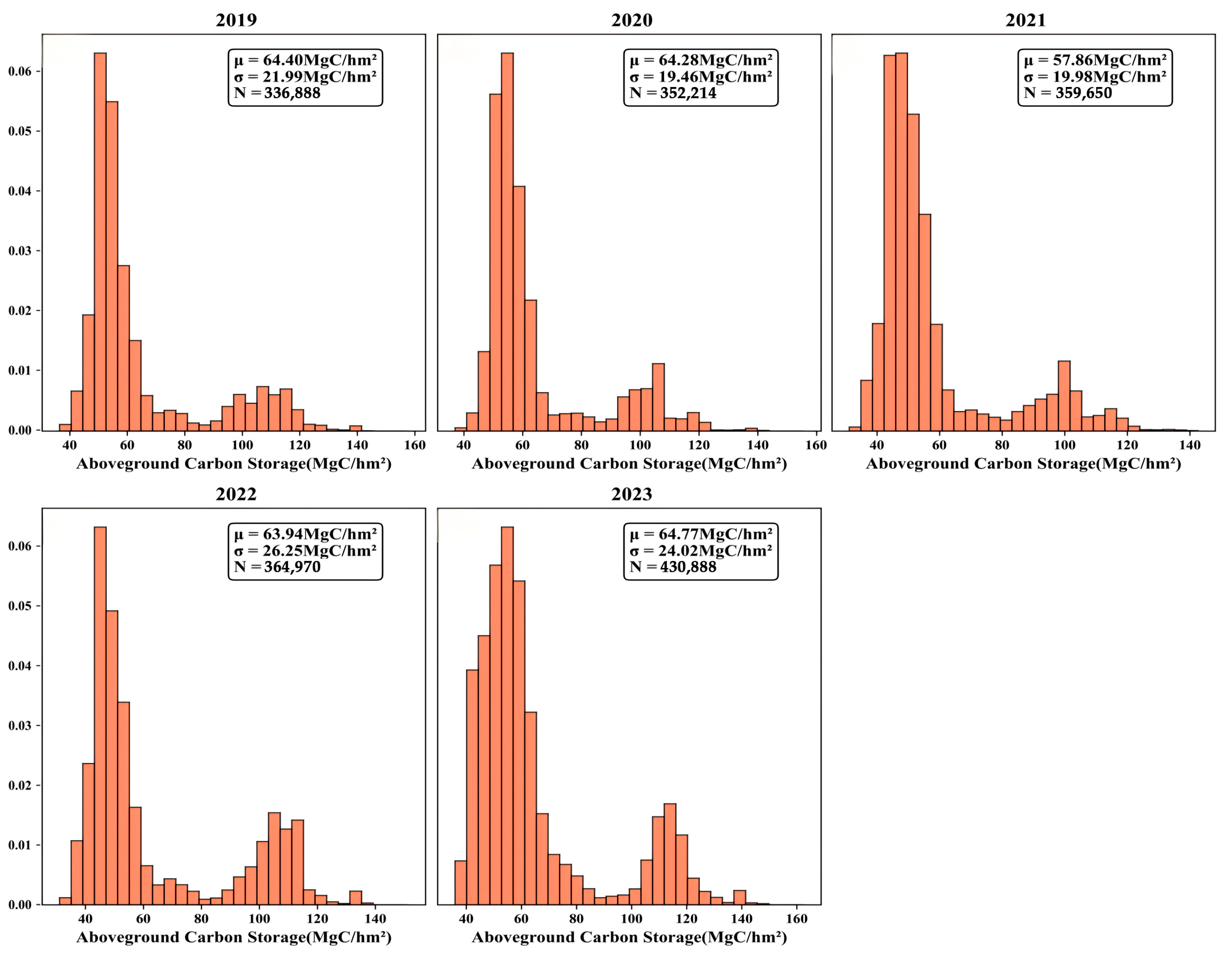

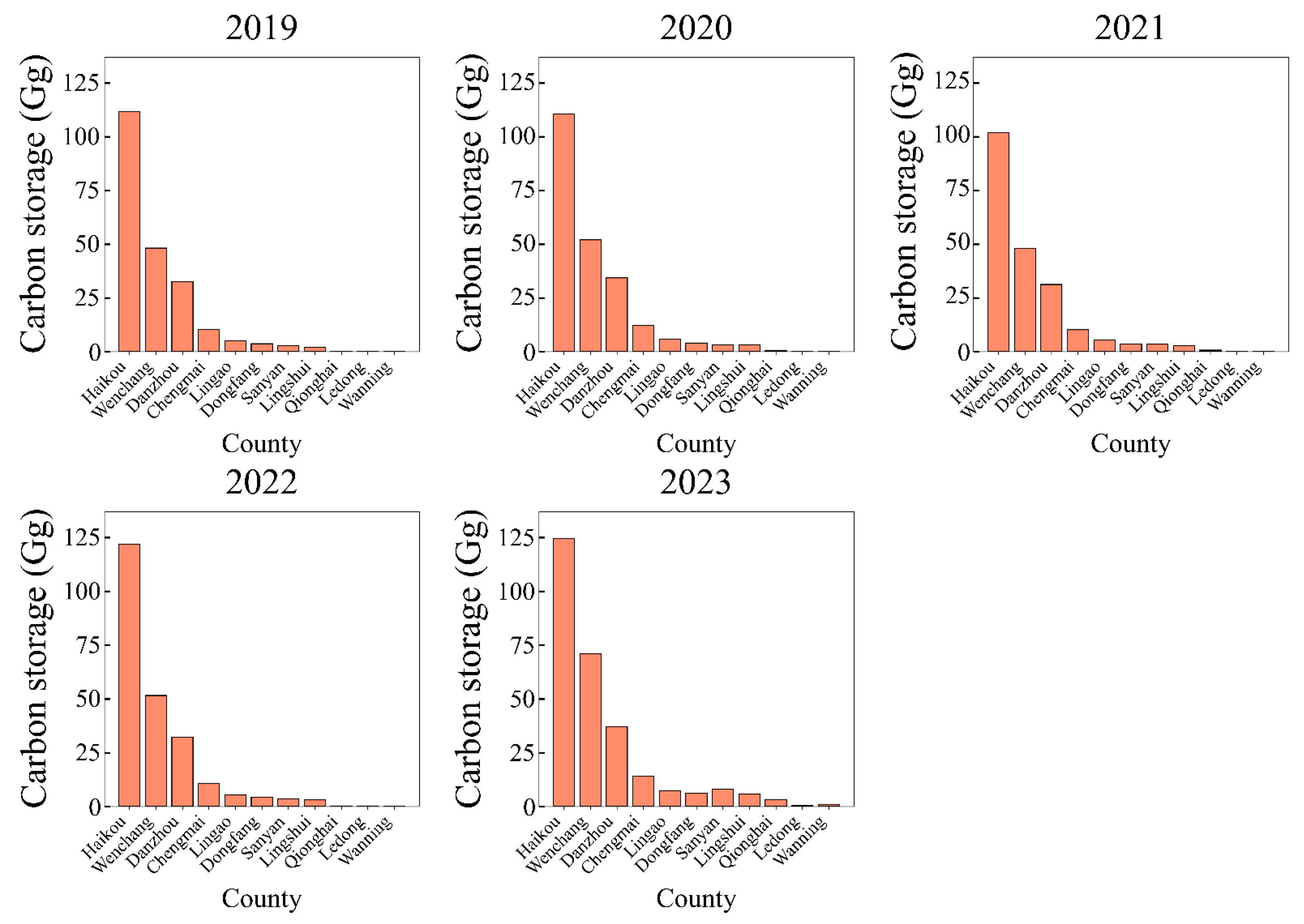

3.4. Changes in Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves, 2019–2023

4. Discussion

4.1. The Applicability of a Deep Learning-Assisted Multi-Rule Remote Sensing Image Synthesis Method

4.2. The Applicability of Machine-Learning-Assisted Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data Fusion Methods

4.3. Ecological Significance

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Confusion Matrix | Reference Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGMF_2020 | Mangrove | Non-mangrove | Total | |

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 4425 | 627 | 5052 |

| Non-mangrove | 783 | 4519 | 5302 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| GMW_V3.0_2020 | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3141 | 614 | 3755 |

| Non-mangrove | 2067 | 4532 | 6599 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| LREIS__v2_2020 | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3971 | 409 | 4380 |

| Non-mangrove | 1237 | 4737 | 5974 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| MR_2020_KNDVI | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3580 | 166 | 3776 |

| Non-mangrove | 1628 | 4950 | 6578 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| MR_2020_MFI | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3295 | 156 | 3451 |

| Non-mangrove | 1913 | 4990 | 6903 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| MR_2020_EVI | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3308 | 166 | 3471 |

| Non-mangrove | 1903 | 4980 | 6883 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| MR__2020_NDWI | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 3515 | 195 | 3710 |

| Non-mangrove | 1693 | 4951 | 6640 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

| MR__2020_Median | ||||

| Classification Results | Mangrove | 4433 | 524 | 4687 |

| Non-mangrove | 775 | 4892 | 5667 | |

| Total | 5208 | 5146 | 10,354 | |

References

- Mumby, P.J.; Edwards, A.J.; Arias-González, J.E.; Lindeman, K.C.; Blackwell, P.G.; Gall, A.; Gorczynska, M.I.; Harborne, A.R.; Pescod, C.L.; Renken, H.; et al. Mangroves enhance the biomass of coral reef fish communities in the Caribbean. Nature 2004, 427, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, S.; Lum, S.K.Y.; Chen, Z. Mangrove root: Adaptations and ecological importance. Trees 2016, 30, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Masud-Ul-Alam, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Rahman Chowdhury, S.; Sharifuzzaman, S. A review of bioturbation and sediment organic geochemistry in mangroves. Geol. J. 2021, 56, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerken, I.; Blaber, S.; Bouillon, S.; Green, P.; Haywood, M.; Kirton, L.G.; Meynecke, J.-O.; Pawlik, J.; Penrose, H.; Sasekumar, A.; et al. The habitat function of mangroves for terrestrial and marine fauna: A review. Aquat. Bot. 2008, 89, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.C.; Kauffman, J.B.; Murdiyarso, D.; Kurnianto, S.; Stidham, M.; Kanninen, M. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhen, J.; Zhang, L.; Metternicht, G. Understanding dynamics of mangrove forest on protected areas of Hainan Island, China: 30 years of evidence from remote sensing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.; Lagomasino, D.; Thomas, N.; Fatoyinbo, T. Global declines in human-driven mangrove loss. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 5844–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.C. Mangrove swamps of the Pacific coast of Colombia. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1956, 46, 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sousa, W.P.; Gong, P.; Biging, G.S. Comparison of IKONOS and QuickBird images for mapping mangrove species on the Caribbean coast of Panama. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Lucas, R.; Itoh, T.; Simard, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Bunting, P.; Rosenqvist, A. An approach to monitoring mangrove extents through time-series comparison of JERS-1 SAR and ALOS PALSAR data. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.; Kainuma, M.; Collins, L. World Atlas of Mangroves; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.D.; Yokoya, N.; Bui, D.T.; Yoshino, K.; Friess, D.A. Remote sensing approaches for monitoring mangrove species, structure, and biomass: Opportunities and challenges. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.; Otero, V.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Lagomasino, D.; Satyanarayana, B.; Fatoyinbo, T.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. Monitoring Matang’s Mangroves in Peninsular Malaysia through Earth observations: A globally relevant approach. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, E.N.; De Jesus, B.R., Jr.; Jara, R.S. Assessment of mangrove forest deterioration in Zamboanga Peninsula, Philippines, using Landsat MSS data. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Symposium on Remote Sensing of the Environment; Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM): Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1979; pp. 1737–1745. [Google Scholar]

- Heumann, B.W. Satellite remote sensing of mangrove forests: Recent advances and future opportunities. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2011, 35, 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, S.E.; Casey, D. Creation of a high spatio-temporal resolution global database of continuous mangrove forest cover for the 21st century (CGMFC-21). Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016, 25, 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.P.; Clark, C.; Mumby, P.; Edwards, A.; Ellis, A. Remote sensing techniques for mangrove mapping. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 935–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, C.; Ochieng, E.; Tieszen, L.L.; Zhu, Z.; Singh, A.; Loveland, T.; Masek, J.; Duke, N. Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, X. Application of deep generative networks for SAR/ISAR: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 11905–11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokas, A.; Rysz, M.; Pardalos, P.M.; Dipple, K. SAR data applications in earth observation: An overview. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Zhang, K.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Ross, M.S.; Ruiz, P.L.; Castañeda-Moya, E.; Twilley, R.R.; Rodriguez, E. Mapping height and biomass of mangrove forests in Everglades National Park with SRTM elevation data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Yu, L.; Cheng, P.; Chen, J.; Chi, C. A comprehensive survey on SAR ATR in deep-learning era. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-K.; Fatoyinbo, T.E. TanDEM-X Pol-InSAR inversion for mangrove canopy height estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 3608–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagomasino, D.; Fatoyinbo, T.; Castañeda-Moya, E.; Cook, B.D.; Montesano, P.M.; Neigh, C.S.; Corp, L.A.; Ott, L.E.; Chavez, S.; Morton, D.C. Storm surge and ponding explain mangrove dieback in southwest Florida following Hurricane Irma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoyinbo, T.E.; Simard, M.; Washington-Allen, R.A.; Shugart, H.H. Landscape-scale extent, height, biomass, and carbon estimation of Mozambique’s mangrove forests with Landsat ETM+ and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission elevation data. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2008, 113, G02S06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. A review of target decomposition theorems in radar polarimetry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 34, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S.; Kugler, F.; Pretzsch, H. Prediction of stem volume in complex temperate forest stands using TanDEM-X SAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 174, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Cao, H.; Tang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, N. 3D urban object change detection from aerial and terrestrial point clouds: A review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.K.; Singh, G.; Routh, J.; Ramanathan, A. Trace metal fractionation in the Pichavaram mangrove–estuarine sediments in southeast India after the tsunami of 2004. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 8197–8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Ooi, J.L.S.; Chen, W.; Poong, S.-W.; Zhang, H.; He, W.; Su, S.; Luo, H.; Hu, W.; Affendi, Y.A.; et al. Heterogeneity of fish taxonomic and functional diversity evaluated by eDNA and Gillnet along a mangrove–seagrass–coral reef continuum. Animals 2023, 13, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Jiang, D.; Tsang, D.C.; Choi, J.; Yip, A.C. Stacking MFI zeolite structures for improved Sonogashira coupling reactions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 276, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Wang, Z.; Mao, D.; Ren, C.; Song, K.; Zhao, C.; Wang, C.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y. Mapping global distribution of mangrove forests at 10-m resolution. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holben, B.N. Characteristics of maximum-value composite images from temporal AVHRR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1986, 7, 1417–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Giri, S.; Chanda, A.; Majumdar, S.D.; Samanta, S.; Mitra, D.; Samal, R.N.; Pattnaik, A.K.; Hazra, S. An index for discrimination of mangroves from non-mangroves using LANDSAT 8 OLI imagery. MethodsX 2018, 5, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.M.; Behera, M.D.; Paramanik, S. Canopy height estimation using sentinel series images through machine learning models in a mangrove forest. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Mapping mangrove using a red-edge mangrove index (REMI) based on Sentinel-2 multispectral images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4409511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Azkab, M.H.; Chmura, G.L.; Chen, S.; Sastrosuwondo, P.; Ma, Z.; Dharmawan, I.W.E.; Yin, X.; Chen, B. Mangroves as a major source of soil carbon storage in adjacent seagrass meadows. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, P.; Rosenqvist, A.; Lucas, R.M.; Rebelo, L.-M.; Hilarides, L.; Thomas, N.; Hardy, A.; Itoh, T.; Shimada, M.; Finlayson, C.M. The global mangrove watch—A new 2010 global baseline of mangrove extent. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloloy, A.B.; Blanco, A.C.; Ana, R.R.C.S.; Nadaoka, K. Development and application of a new mangrove vegetation index (MVI) for rapid and accurate mangrove mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 166, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.V.; Reef, R.; Zhu, X. A review of spectral indices for mangrove remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzer, C.; Bluemel, A.; Gebhardt, S.; Quoc, T.V.; Dech, S. Remote sensing of mangrove ecosystems: A review. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 878–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Treitz, P.M.; Chen, D.; Quan, C.; Shi, L.; Li, X. Mapping mangrove forests using multi-tidal remotely-sensed data and a decision-tree-based procedure. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 62, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ding, L.; Tian, X.; Tao, D. On efficient training of large-scale deep learning models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Young, M.; Macreadie, P.I.; Nicholson, E.; Ierodiaconou, D. Mangrove and saltmarsh distribution mapping and land cover change assessment for south-eastern Australia from 1991 to 2015. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloloy, A.B.; Blanco, A.C.; Candido, C.G.; Argamosa, R.J.L.; Dumalag, J.B.L.C.; Dimapilis, L.L.C.; Paringit, E.C. Estimation of mangrove forest aboveground biomass using multispectral bands, vegetation indices and biophysical variables derived from optical satellite imageries: Rapideye, planetscope and sentinel-2. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, P.; Danoedoro, P.; Hartono; Nehren, U. Mangrove biomass carbon stock mapping of the Karimunjawa Islands using multispectral remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, E.; Kamal, M.; Wicaksono, P. Comparison of vegetation indices for estimating above-ground mangrove carbon stocks using PlanetScope image. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 44, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, P. Mangrove above-ground carbon stock mapping of multi-resolution passive remote-sensing systems. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 1551–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, O.; Aziz, H.K.; Hasmadi, I.M. L-band ALOS PALSAR for biomass estimation of Matang Mangroves, Malaysia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 155, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, L. The current status, potential and challenges of remote sensing for large-scale mangrove studies. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 6824–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Rui, X.; Zou, Y.; Tang, H.; Ouyang, N. Mangrove monitoring and extraction based on multi-source remote sensing data: A deep learning method based on SAR and optical image fusion. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2024, 43, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, W.; Deng, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Estimation of Mangrove Aboveground Carbon Using Integrated UAV-LiDAR and Satellite Data. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, A.; Ong, J.E.; Poungparn, S. Allometry, biomass, and productivity of mangrove forests: A review. Aquat. Bot. 2008, 89, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavzoglu, T. Object-oriented random forest for high resolution land cover mapping using quickbird-2 imagery. In Handbook of Neural Computation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the KDD ’16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Che, T.; Ma, M.; Tan, J.; Wang, H. Corn biomass estimation by integrating remote sensing and long-term observation data based on machine learning techniques. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Sun, M. Assessment of intertidal seaweed biomass based on RGB imagery. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagomasino, D.; Fatoyinbo, T.; Lee, S.; Feliciano, E.; Trettin, C.; Simard, M. A comparison of mangrove canopy height using multiple independent measurements from land, air, and space. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, J.; Smith, A.R.; Yang, D.; Ma, T.; Su, Y.; Shao, J. Evaluation of machine learning methods and multi-source remote sensing data combinations to construct forest above-ground biomass models. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 4471–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D.; Le, N.N.; Ha, N.T.; Nguyen, L.V.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N.; To, T.T.; Trinh, H.X.; Kieu, L.Q.; Takeuchi, W. Estimating mangrove above-ground biomass using extreme gradient boosting decision trees algorithm with fused sentinel-2 and ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 data in can Gio biosphere reserve, Vietnam. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J.; McRoberts, R.E.; Fernández-Landa, A.; Tomé, J.L.; Nӕsset, E. Estimating forest volume and biomass and their changes using random forests and remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.-H.; Larocque, D. Robustness of random forests for regression. J. Nonparametric Stat. 2012, 24, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, L.; Myint, S.W.; Wang, S.; Cao, J.; Wu, Z. Estimating and mapping mangrove biomass dynamic change using WorldView-2 images and digital surface models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Su, Y.; Xue, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Fang, J.; Guo, Q. Mapping global forest aboveground biomass with spaceborne LiDAR, optical imagery, and forest inventory data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, S.; Callow, N.; Phinn, S.; Lovelock, C.; Duarte, C.M. Spatial complexities in aboveground carbon stocks of a semi-arid mangrove community: A remote sensing height-biomass-carbon approach. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 200, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Smetanka, C.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Castañeda-Moya, E.; Thomas, N.; Van der Stocken, T. Mangrove canopy height globally related to precipitation, temperature and cyclone frequency. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Meng, Y.; Gou, R.; Lyu, J.; Dai, Z.; Diao, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, X.; Lin, G. Mangrove diversity enhances plant biomass production and carbon storage in Hainan island, China. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Song, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, J.; Fang, Y.; Cao, B.; Qiu, Z. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution of mangrove forests in the Hainan Island from 1991 to 2021 based on SVM and Res-UNet Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Remote Sensing Factors | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-2 Band Reflectance 11 | B2 | Blue light band, centre wavelength 0.490 μm |

| B3 | Green light band, centre wavelength 0.560 μm | |

| B4 | Red light band, centre wavelength 0.665 μm | |

| B5 | Vegetation Red Edge Band, Centre Wavelength 0.705 μm | |

| B6 | Vegetation Red Edge Band, Centre Wavelength 0.740 μm | |

| B7 | Vegetation Red Edge Band, Centre Wavelength 0.783 μm | |

| B8 | Near-infrared band, centre wavelength 0.842 μm | |

| B8A | Vegetation Red Edge Band, Centre Wavelength 0.865 μm | |

| B9 | Water vapour band, centre wavelength 0.945 μm | |

| B11 | Shortwave infrared band, centre wavelength 1.610 μm | |

| B12 | Shortwave infrared band, centre wavelength 2.190 μm | |

| Sentinel-2 Derived Vegetation Index 17 | RVI | Ratio Vegetation Index, B8/B4 |

| DVI | Differential Vegetation Index, B8 − B4 | |

| WDVI | Weighted Difference Vegetation Index, B8 − 0.5 × B4 | |

| IPVI | Infrared Percentage Vegetation Index, B8/(B8 + B4) | |

| NDVI | Normalized Vegetation Index, (B8 − B4)/(B8 + B4) | |

| NDI45 | Optimize the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, (B5 − B4)/(B5 + B4) | |

| GNDBI | Green Band Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (B7 − B3)/(B7 + B3) | |

| SAVI | Soil Regulation Vegetation Index, 1.5 × (B8 −B4)/8 × (B8 + B4 + 0.5) | |

| TSAVI | Converted soil conditioning vegetation index, 0.5 × (B8 − 0.5 × B4 − 0.5)/(0.5 × B8 + B4 − 0.15) | |

| MSAVI | Corrected Soil Adjustment Index, (2 − NDVI × WDVI) × (B8 − B4)/8 × (B8 + B4 + 1 − NDVI × WDVI) | |

| ARVI | Atmospheric Correction Vegetation Index, [B8 − (2 × B4 − B2)]/[B8 + (2 × B4 − B2)] | |

| PSSRa | Simple Ratio Index of Characteristic Pigments, B7/B4 | |

| MTCI | Medium-resolution terrestrial chlorophyll index, (B6 − B5)/(B5 − B4) | |

| MCARI | Improved chlorophyll absorption ratio index, [(B5 − B4) − 0.2 × (B5 − B3)] × (B5 − B4) | |

| S2REP | Sentinel-2 Red Edge Position Index, 705 + 35 × [(B4 + B7)/2 − B5]/(B6 − B5) | |

| REIP | Red-bordered curvature position index, 700 + 40 × [(B4 + B7)/2 − B5]/(B6 − B5) | |

| GEMI | Global Environmental Monitoring Index, eta × (1 − 0.25 × eta) − (B4 − 0.125)/(1 − B4), In the formula eta = [2 × (B8A − B4) + 1.5 × B8A + 0.5 × B4]/(B8A + B4 + 0.5) | |

| Sentinel-2 Band Texture Features 88 (3 × 3 window) | B1–B12 Contrast | Contrast reflects the sharpness of an image |

| B1–12 Dissimilarity | Diversity is analogous to contrast; the higher the local contrast, the greater the diversity | |

| B1–12 Mean | The uniformity of dispersion of mean-reversed pixel grey values within the image | |

| B1–12 Homogeneity | Coherence reflects the uniformity of local grey levels within an image | |

| B1–12 Second Moment | The second-order moment reflects the uniformity and thickness characteristics of texture information in the distribution of grey values within an image | |

| B1–12 Entropy | Entropy reflects the complexity of texture within an image | |

| B1–12 Variance | Variance inverse image element value and mean deviation | |

| B1–12 Correlation | The correlation reflects the similarity between elements in the rows and columns of the grey-scale co-occurrence matrix | |

| Sentinel-1 Normalized Backscatter Coefficient | VV | VV’s backscatter coefficient |

| VH | VH’s backscattering coefficient |

| Vegetation Index | Abbreviation | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel Normalized Difference Kernel | KNDVI | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | EVI | |

| Normalized Difference Water Index | NDWI | |

| Mangrove Forest Index | MFI |

| Mangrove | Non-Mangrove | |

|---|---|---|

| precision | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| recall | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| F1-score | 0.91 | 0.99 |

| Data Source | Category | Accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer Accuracy % | User Accuracy % | Overall Precision % | Kappa Coefficient % | ||

| HGMF_2020 | Mangrove | 87.6 | 84.9 | 86.3 | 72.6 |

| Non-mangrove | 85.2 | 88.0 | |||

| GMW_V3.0_2020 | Mangrove | 83.6 | 60.3 | 74.1 | 50.0 |

| Non-mangrove | 68.6 | 88.0 | |||

| LREIS__v2_2020 | Mangrove | 90.6 | 76.3 | 84.1 | 68.2 |

| Non-mangrove | 79.3 | 92.0 | |||

| MR_2020_KNDVI | Mangrove | 94.8 | 68.7 | 82.3 | 64.7 |

| Non-mangrove | 75.2 | 96.1 | |||

| MR_2020_MFI | Mangrove | 94.8 | 68.7 | 80.0 | 60.1 |

| Non-mangrove | 75.6 | 96.9 | |||

| MR_2020_EVI | Mangrove | 95.2 | 63.4 | 80.0 | 60.2 |

| Non-mangrove | 72.3 | 96.8 | |||

| MR__2020_NDWI | Mangrove | 94.7 | 67.5 | 81.8 | 63.7 |

| Non-mangrove | 74.5 | 96.2 | |||

| MR__2020_Median | Mangrove | 94.6 | 85.1 | 90.0 | 80.0 |

| Non-mangrove | 86.3 | 95.0 | |||

| Municipal and County | 2019 (ha) | 2020 (ha) | 2021 (ha) | 2022 (ha) | 2023 (ha) | Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengmai | 224.66 | 242.14 | 230.47 | 252.44 | 238.92 | +6.35% |

| Dongfang | 75.48 | 80.55 | 84 | 112.61 | 99.38 | +31.66% |

| Wenchang | 947.21 | 977.01 | 1009.75 | 1021.59 | 1083.83 | +14.42% |

| Ledong | 4.19 | 4.68 | 5.85 | 8.52 | 8.51 | +103.10% |

| Haikou | 1775.08 | 1762.93 | 1798.34 | 1841.39 | 1817.85 | +2.41% |

| Sanya | 78.27 | 84.74 | 90.8 | 100.04 | 107.39 | +37.20% |

| Lingshui | 44.8 | 63.9 | 67.89 | 73.86 | 94.97 | +111.99% |

| Wanning | 7.7 | 8.77 | 8.23 | 6.56 | 12.31 | +59.87% |

| Danzhou | 644.46 | 655.45 | 653.81 | 671.27 | 668.61 | +3.75% |

| Lingao | 134.12 | 141.97 | 145.39 | 135.55 | 130.76 | −2.51% |

| Qionghai | 12.86 | 27.43 | 20.88 | 10.96 | 41.76 | +224.73% |

| Hainan Island | 3948.83 | 4049.57 | 4115.41 | 4234.79 | 4304.29 | +9.00% |

| Model Algorithms | R2 | Bias (m) | Relative Bias (%) | RMSE (m) | RRMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGboost | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 1.35 | 39.86 |

| GBDT | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 1.39 | 39.84 |

| RF | 0.83 | 0.07 | 2.00 | 1.35 | 39.76 |

| Model Algorithms | R2 | Bias (MgC/hm2) | Relative Bias (%) | RMSE (MgC/hm2) | RRMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGboost | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 20.90 | 35.99 |

| GBDT | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 19.01 | 36.52 |

| RF | 0.67 | 4.46 | 4.38 | 17.33 | 34.05 |

| Municipal and County | 2019 (m) | 2020 (m) | 2021 (m) | 2022 (m) | 2023 (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengmai | 4.84 | 4.87 | 5.22 | 4.35 | 4.23 |

| Dongfang | 4.70 | 5.46 | 5.67 | 3.63 | 4.24 |

| Wenchang | 4.62 | 5.02 | 5.26 | 4.87 | 4.35 |

| Ledong | 2.95 | 3.62 | 3.97 | 3.88 | 2.59 |

| Haikou | 4.62 | 4.57 | 4.80 | 4.34 | 4.13 |

| Sanya | 5.41 | 5.68 | 5.87 | 5.32 | 4.97 |

| Lingshui | 3.74 | 3.82 | 3.80 | 3.33 | 3.26 |

| Wanning | 5.49 | 5.70 | 6.22 | 5.83 | 4.59 |

| Danzhou | 4.10 | 4.06 | 4.14 | 3.25 | 3.88 |

| Lingao | 4.64 | 4.66 | 4.68 | 3.94 | 3.86 |

| Qionghai | 5.65 | 5.80 | 6.05 | 5.78 | 5.18 |

| Hainan Island | 4.24 | 4.64 | 4.70 | 4.82 | 4.30 |

| Municipal and County | Year | Area (hm2) | Aboveground Carbon Storage Density (Mg C ha−1) | Aboveground Carbon Storage (GgC) | Carbon Sink (GgC/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengmai | 2019 | 224.66 | 58.8 | 13.21 | / |

| 2020 | 242.14 | 63.03 | 15.26 | 2.05 | |

| 2021 | 230.47 | 52.33 | 12.06 | −3.20 | |

| 2022 | 252.44 | 53.73 | 13.56 | 1.50 | |

| 2023 | 238.92 | 58.43 | 13.96 | 0.40 | |

| Dongfang | 2019 | 75.48 | 63.18 | 4.77 | / |

| 2020 | 80.55 | 63.23 | 5.09 | 0.32 | |

| 2021 | 84 | 58.22 | 4.89 | −0.20 | |

| 2022 | 112.61 | 58.01 | 6.53 | 1.64 | |

| 2023 | 99.38 | 62.88 | 6.25 | −0.28 | |

| Wenchang | 2019 | 947.21 | 56.5 | 53.52 | / |

| 2020 | 977.01 | 58.49 | 57.15 | 3.63 | |

| 2021 | 1009.75 | 51.38 | 51.88 | −5.26 | |

| 2022 | 1021.59 | 50.29 | 51.38 | −0.51 | |

| 2023 | 1083.83 | 55.74 | 60.41 | 9.04 | |

| Ledong | 2019 | 4.19 | 67.79 | 0.28 | / |

| 2020 | 4.68 | 66.5 | 0.31 | 0.03 | |

| 2021 | 5.85 | 60.33 | 0.35 | 0.04 | |

| 2022 | 8.52 | 71.32 | 0.61 | 0.25 | |

| 2023 | 8.51 | 67.45 | 0.57 | −0.03 | |

| Haikou | 2019 | 1775.08 | 54.16 | 96.14 | / |

| 2020 | 1762.93 | 55.39 | 97.65 | 1.51 | |

| 2021 | 1798.34 | 56.61 | 101.80 | 4.16 | |

| 2022 | 1841.39 | 55.71 | 102.58 | 0.78 | |

| 2023 | 1817.85 | 56.29 | 102.33 | −0.26 | |

| Sanya | 2019 | 78.27 | 60.35 | 4.72 | / |

| 2020 | 84.74 | 63.73 | 5.40 | 0.68 | |

| 2021 | 90.8 | 56.63 | 5.14 | −0.26 | |

| 2022 | 100.04 | 56.86 | 5.69 | 0.55 | |

| 2023 | 107.39 | 60.46 | 6.49 | 0.80 | |

| Lingshui | 2019 | 44.80 | 59.58 | 2.67 | / |

| 2020 | 63.9 | 59.63 | 3.81 | 1.14 | |

| 2021 | 67.89 | 51.86 | 3.52 | −0.29 | |

| 2022 | 73.86 | 53.09 | 3.92 | 0.40 | |

| 2023 | 94.97 | 58.68 | 5.57 | 1.65 | |

| Wanning | 2019 | 7.7 | 61.19 | 0.47 | / |

| 2020 | 8.77 | 60.69 | 0.53 | 0.06 | |

| 2021 | 8.23 | 55.65 | 0.46 | −0.07 | |

| 2022 | 6.56 | 57.17 | 0.38 | −0.08 | |

| 2023 | 12.31 | 64.1 | 0.79 | 0.41 | |

| Danzhou | 2019 | 644.46 | 60.15 | 38.76 | / |

| 2020 | 655.45 | 61.01 | 39.99 | 1.22 | |

| 2021 | 653.81 | 57.76 | 37.76 | −2.22 | |

| 2022 | 671.27 | 57.63 | 38.69 | 0.92 | |

| 2023 | 668.61 | 61.28 | 40.97 | 2.29 | |

| Lingao | 2019 | 134.12 | 56.23 | 7.54 | / |

| 2020 | 141.97 | 59.26 | 8.41 | 0.87 | |

| 2021 | 145.39 | 59.53 | 8.66 | 0.24 | |

| 2022 | 135.55 | 51.59 | 6.99 | −1.66 | |

| 2023 | 130.76 | 63.94 | 8.36 | 1.37 | |

| Qionghai | 2019 | 12.86 | 61 | 0.78 | / |

| 2020 | 27.43 | 62 | 1.70 | 0.92 | |

| 2021 | 20.88 | 55.16 | 1.15 | −0.55 | |

| 2022 | 10.96 | 59.01 | 0.65 | −0.50 | |

| 2023 | 41.76 | 60.42 | 2.52 | 1.88 | |

| Hainan Island | 2019 | 3948.83 | 64.40 | 254.30 | / |

| 2020 | 4049.57 | 64.28 | 260.30 | 6.00 | |

| 2021 | 4115.41 | 57.86 | 238.11 | −22.18 | |

| 2022 | 4234.79 | 63.94 | 270.77 | 32.65 | |

| 2023 | 4304.29 | 64.77 | 278.79 | 8.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, W.; Feng, Z.; Pei, H.; Grimaldi, P.; Qiu, Z. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Forests 2026, 17, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010131

Liu Z, Yin Z, Zhao W, Feng Z, Pei H, Grimaldi P, Qiu Z. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Forests. 2026; 17(1):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010131

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhikuan, Zhaode Yin, Wenlu Zhao, Zhongke Feng, Huiqing Pei, Pietro Grimaldi, and Zixuan Qiu. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data" Forests 17, no. 1: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010131

APA StyleLiu, Z., Yin, Z., Zhao, W., Feng, Z., Pei, H., Grimaldi, P., & Qiu, Z. (2026). Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aboveground Carbon Storage in Hainan Mangroves Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Forests, 17(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010131